Openness versus helplessness: Europe’s 2015-2017 border crisis

Hugo Brady

28/06/2021

28/06/2021

Voir tous les articles

Voir tous les articles

Openness versus helplessness: Europe’s 2015-2017 border crisis

Prologue

It is October 20th 2015. Smugglers in the Turkish ports of Izmir and Bodrum are frantic, scurrying up and down the shoreline to push thousands of people in rubber dinghies and makeshift boats out into the Aegean 1 . The Greek island of Kos rises up, less than a kilometre away. In line with international search and rescue (SAR) rules, exhausted EU sea patrols pick up the clandestine travellers and hurriedly disembark them in Kos as well as neighbouring Chios, Lesbos, Samos and Leros. Almost all claim asylum as Syrian war refugees, be they Afghan, Iraqi, Pakistani, Moroccan or from sub-Saharan Africa. They receive hastily scribbled transit stubs, a boat to mainland Greece and from there buses to the beginning of a refugee trailhead at the North Macedonian border. Via the ‘Balkan route’, they will leave and re-enter the European Union, transiting through Austria and Hungary, destined for Germany or Sweden. Chiming, vibrating notifications on the migrants’ smartphones seem to confirm the promises of the smugglers: those determined enough to make the journey are receiving cash handouts and free housing in northern Europe. What the Swiss give to asylum claimants in one year alone equals a lifetime’s wages in Afghanistan. An air-punching chant goes up from the migrant assembly, full of hope, bitter frustration and the energy of despair. GER-MAN-NY!! GER-MAN-NY!! GER-MAN-NY!! GER-MAN-NY!!

Regardless of ethnicity or origin, the travellers move as a cohort now, assuming that authorities up ahead cannot stop groups of 1,000 or more. They are right. North Macedonia declares a national state of emergency in August when 112,000 openly walk over its frontier with Greece. In September a further 150,000 cross, prompting Hungary to seal off its border with Serbia. Buoyed by high-fives and bottled water from ordinary Serbs, the mass of people wheels around and heads for Croatia. Ever the obliging neighbour, Croatia buses the influx straight to Slovenia, the gateway to the rest of the EU’s passport-free zone. The Slovenes send their army to the border and cap those allowed across to 2,500 per day. The numbers merely mount and bulge around the bottleneck, and in the end the Slovenes are forced to give way. Almost a quarter of a million enter that October, nationalities and intentions unknown as no serious screening takes place at the point of entry in Greece, or elsewhere. No-one is in control. Across the continent, TV pictures of marching migrants trigger Europe’s fight-or-flight response. Creeping unease turns to panic.

Governments along the route fear that the migrants will settle if made too comfortable. They compete to move them on as quickly as possible, maintaining the charade of catering to the inflow whilst keeping humanitarian efforts to the bare minimum. For, when borders inevitably close somewhere in northern Europe, poor Balkan communities will be left with large numbers of mainly men from the Middle East and Africa, and neither the resources nor the desire to integrate them. These considerations are also in the mind of Alexis Tsipras, the Greek prime minister. Employing humanitarian rhetoric as his shield, Tsipras refuses the help from the EU with registration and screening that could at least restore a semblance of order at the point of arrival. The Syriza leader fears his bankrupt country becoming what he will later term a “warehouse of souls”. To the despair of his fellow European leaders, Tsipras remains incommunicado as he waves the migrants on through Greece as quickly as possible, like a policeman directing traffic. Even the coming of the winter weather gives no respite as the smugglers shove more and more people into the plunging seas. Downstream, the International Red Cross sounds the alarm that Europe will have lives on its conscience if the migrants — many of whom have never seen snow before — become stranded in the mountainous Balkans…

Introduction

“We can no longer allow solidarity to be equivalent to naivety, openness to be equivalent to helplessness, freedom to be equivalent to chaos. And by that, I am of course referring to the situation on our borders.” Donald Tusk, President of the European Council, at the European Peoples Party Congress in Madrid, October 22nd 2015.

October 2015 marked the nadir of a three-year border crisis where European ideals of openness and humanitarianism collided with the terrible realities of mass maritime migration and the forced displacement of people. The emergency followed hard on the heels of the Eurozone crisis and revealed the EU’s border and asylum system, robust on paper, as often bereft of content. As with the euro crisis, the migrant upheaval went on longer than necessary, took on a self-fulfilling character, and became a political arm-wrestle between principle and pragmatism for European leaders: a proxy for their clashing worldviews. Again like the single currency, the various solutions proffered were criticised energetically, either as utterly naïve or unsettlingly immoral.

From very early on, the whole episode was shaped to a considerable degree by an alliance of actors who insisted there was no alternative other than the mandatory distribution of asylum claimants between EU countries, despite this concept having never been heard of or attempted before anywhere. Their conspiracy of hope included most of the Mediterranean countries, an ambitiously integrationist European Commission and Parliament, a German chancellor backed into a corner and her allies, a UN refugee agency (UNHCR) attempting to expand global protection space, and open borders activists playing a Jacobin role.

For many, their motives matter more than the outcome, laying down a precedent for the realisation of such a system in the future. However, the legacy is a painful one, including a new defining political split within the Union and a perhaps permanently damaged Schengen area where internal border checks remain in place over half a decade later. Also, the blow struck to the EU’s popular legitimacy, just as it faced a terror threat from Islamist extremists and the looming prospect of Brexit, should not be underestimated. In the end, it mattered a lot.

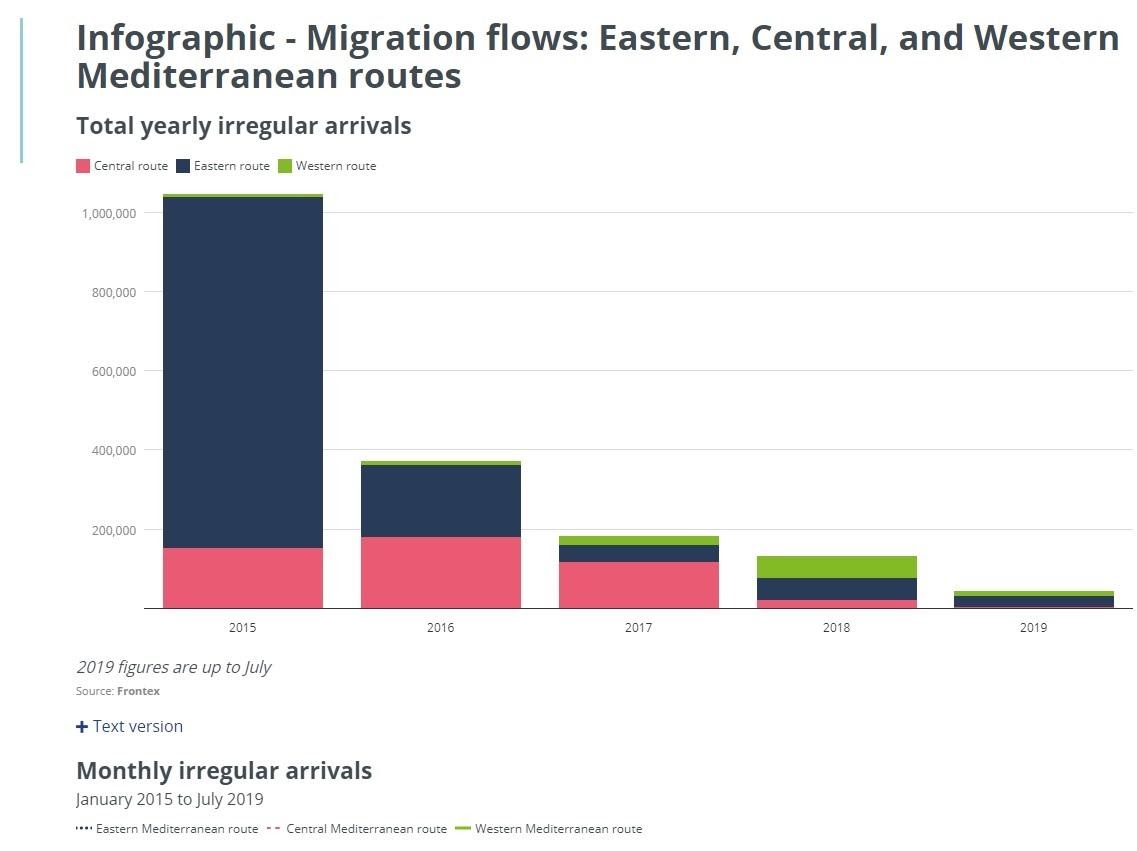

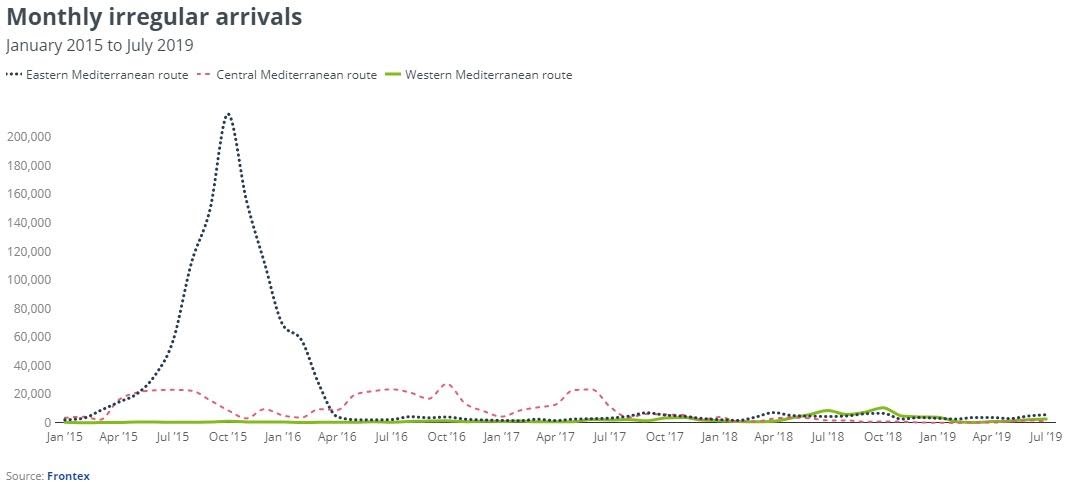

Notwithstanding this, the Union performed a remarkable feat to end the biggest maritime migration crisis in history. This was despite its own internal divisions, still keenly felt; despite having few tools for the task; and despite its geographic and legal vulnerability to a globalised people smuggling phenomenon. A measure of this success is that it is now difficult to recall the apocalyptic sense of fear that ran through Europe in 2015 and early 2016 when over 1.2 million people from the Middle East, Africa and South Asia arrived irregularly to its shores (see graphs I and II). If memories of migrants marching down motorways or children drowned on beaches have faded, along with the despair and outrage that accompanied them, it is because Europe did, in the end, stem the flows, restoring order. The key was resisting the gravitational pull of the absolutes on offer: full open borders, never ending acrimony and chaos; or a return to national frontiers eventually collapsing Europe’s single market. Instead, the Union reorganised itself in phases around the protection of its external border, drawing belatedly on the lessons of other comparable crises.

The article examines the internal and external factors that led to the crisis and charts its key phases including the debates that raged between EU leaders from April 2015. Then there is an analysis of Europe’s response, followed by an attempt to categorise the responses of smaller states to both the flows and the political upheaval. At the end, a few reflections are offered on the aftermath and legacy.

The crisis: origins and evolution

What some commentators have termed “Europe’s 9/11” (Krastev 2017: 1, 13) was, in essence, a boat crisis. Greater in scale than any in modern history, the episode shared clear parallels with the Vietnam boat crisis of the late 1970s, the flight of Cubans to the US in the 1980s and 1990s, or Australia’s various attempts to stem spontaneous arrivals from south-east Asia since 2001. What made Europe’s case distinct was the European Union itself and the specifics of three of its legal regimes.

First, the EU is unique in the world because there are no passport controls between most of its countries, even though they remain sovereign. This is due to the creation of the passport-free Schengen area in 1995 and the common external border, expanded to Greece in 2000 and to most countries in central and eastern Europe in 2007. Second, the EU’s executive – the European Commission – has no powers to intervene at the external border. Open borders within rest on the assumption countries will deny entry to foreigners without bone fide access at their own part of the external border and assess the validity of claims by irregular arrivals to political asylum. Since 2003, the EU’s interpretation of its obligations under the Geneva Convention 2 , known as the common European asylum system 3 , has set out how asylum seekers should be received and interviewed, but leaves issues like economic support broadly to national discretion 4 . The cornerstone principle – laid down in the EU’s so-called Dublin regulation – is that the European country an asylum seeker enters first is supposed to hear their claim, up to a year after arrival. Hence, if an asylum seeker arrives in Italy and six months later applies for economic support in Norway, the Norwegian authorities are within their rights to send that person back to Italy for adjudication 5 . If the claim is then rejected, as typically at least 50 per cent are, Italy should return the claimant back to their country of origin 6 . (The rule works the other way around for Italy if, for example, the country of first entry is Norway.)

Third, every EU country is party to the European Convention on Human Rights. In 2012, the Strasbourg Court issued a ruling known as the Hirsi judgement, ending Italy’s practice of turning back smuggler boats before they could reach its territorial waters 7 . The ruling gave irregular migrants picked up by ships on the high seas access to the European asylum procedure, which takes hours of interviews and a long adjudication process including appeals. The Court found a formula to achieve this indirectly, obliging vessels with a European flag to disembark people rescued in international waters at the nearest port in Europe, to verify if anyone on board might be a refugee. No other signatory of the 1951 refugee convention interprets its obligations in this way. No such right exists, say, in international waters off the coast of Canada, or in the Caribbean, where US authorities rapidly determine status on deck by checking for ‘manifestation of fear’. In the central Mediterranean, people smuggling cartels in Libya and Tunisia soon realised every European vessel near their coasts was now potentially a floating taxi to Europe. This legal revolution coincided with Libya’s collapse into lawlessness after the fall of the Gadhafi regime in 2011, and the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in earnest the following year. The stage was set for Schengen’s descent 8 .

At first, the numbers of boat people intercepted remained tolerable. In 2012, 13,000 came, picked up willy-nilly by merchant shipping or the Italian coastguard, which might not actively go searching on the high seas under the new legal reality, but would not ignore a distress call either. However, on October 3rd 2013, 366 Africans were shipwrecked and drowned off the tiny Italian island of Lampedusa, the closest littoral point in Europe to the North African coast. Horrified, the Italians began systematic patrolling in international waters two days later. Code-named Operation Mare Nostrum (Our Sea), the patrols took the form of a large ‘military humanitarian’ mission with a sparkling range of aerial and naval assets, including a floating hospital. By any standards, the deployment was big, public, decisive. But to confront the situation this way was to blunder into a trap, laid by the smuggling cartels 9 . Over the following months, arrivals skyrocketed to more than 170,000. So did the deaths: to over 3,000 from 644 the year before. Now huddled in the boats amongst the west Africans and Eritreans, Syrians were using Turkey’s visa-free regime with Libya as a back door to Europe.

Unable to withdraw a mercy mission in the public eye, the Italian government — under a new prime minister, Matteo Renzi — needed an out. Renzi’s answer was to Europeanise the situation by getting the EU to take over the patrols. On October 31st 2014, Mare Nostrum was stood down to be replaced by Operation Triton, managed by the EU’s border agency, Frontex 10 . Led by Italy and Malta with ten more EU countries lending assets and manpower, the rescued would still be disembarked in Italian ports. What mattered was the handover from a naval to a border mission afforded the Italians sleight of hand to slim down the patrols and pull them back within territorial waters.

But the smugglers had Italy hooked like a fish and were never going to let go that easily. The message sent by the Mare Nostrum deployment was clear: Europe would not turn back irregular arrivals, which was the same thing as saying it would welcome them. From August 2014 on, NGOs began arriving to the international patrol area, the first being Migrant Off-Shore Aid Station or MOAS. The NGOs would sail up to Libyan waters to pick up migrants pushed out from the coast, head back to Italian waters and hand those rescued over to the authorities. They accounted for an increasingly large share of the disembarked, eventually expanding to a fleet of 14 ships, often equipped with drones and other equipment to scan the seas for vessels floating aimlessly. Despite all the extra patrolling, the biggest disaster yet was on the horizon. In April 2015, two rusting cargo ships capsized just a few days apart close to Libyan waters, killing 1,200 people.

Hitherto EU leaders had resisted Italian pressure to make its sea rescues a European problem. Borders, asylum seekers, immigration: these were hyper-sensitive, fiddly matters for interior ministers to handle. Though obviously important, they were not Chefsache. The alpha males and alpha females in the European Council, the EU’s highest decision-making body, were utterly unfamiliar with them 11 . Now the April disasters meant Italy’s insistence could be denied no longer. Donald Tusk, president of the European Council and prime minister of Poland until 2014, called an emergency meeting of the leaders on April 23rd. Tusk was deeply unenthusiastic about drawing the Union any further into the smugglers’ net than it was already. Above all a political communicator, he thought the smugglers and migrants needed to hear, and quickly, the unambiguous message that Europe would stop the taxi service. Any other course of action meant a ratcheting up of the crisis: more boats, more deaths, more internal chaos in the EU. But his cut-to-the-chase approach went against the grain of the Union’s established practice of tackling intractable challenges with ‘constructive ambiguity’ and the soothing balm of comprehensiveness.

Like a castle in fog, the April European Council lay shrouded in political confusion. Some advisors were counselling their leaders – including Germany’s – that European asylum rules simply left no room to prevent however many irregular arrivals coming en masse, if they chose. This legal fatalism, alongside the leaders’ unfamiliarity with the issue on the table, fed a sense of helplessness. Hence April began a long waltz that would take two years to dance between hard-headed steps needed to end the crisis and pressure to be seen responding to it in line with ‘European values’. Luuk van Middelaar, author and political philosopher, has characterised this tension in terms from Max Weber’s Politics as a Vocation (1919), between Weber’s ‘ethic of responsibility’, (“in which case one has to give an account of the foreseeable results of one’s actions”), and the ‘ethic of conviction’, (“where the Christian does rightly and leaves the results with the Lord”). (van Middelaar 2018: 3, pp. 91-114) With no good options now before them, the ongoing crisis was forcing EU leaders in front of the cameras to pantomime one ethic or the other.

The summit tripled the resources available to Operation Triton with even Britain contributing a battleship, HMS Bulwark. Leaders stretched Triton’s territorial mandate to breaking point, in practice enabling Frontex to conduct SAR operations much as Mare Nostrum had done. They knew the arrivals, and almost certainly the deaths, would rise but left these considerations “with the Lord”. In a similar vein, the leaders also sketched a plan to relieve Italy via ‘temporary relocation’, meaning the distribution of asylum seekers around the Union, under a discretionary clause in its Dublin rules 12 .

Contrary to popular perception, the people in the boats were not Libyans. Libya was for decades past a destination for sub-Saharan workers, who performed the majority of agricultural and service jobs in the oil-rich country’s labour market. (And who, even in good times, could fall prey to an endemic culture of indentured servitude or debt bondage — in other words: slavery.) Post-Gadhafi, state and society were torn between hostile factions in Tripoli and Tobruk. Libya’s erstwhile labour migrants had no-one to turn to but the smugglers; while the Europeans had no-one in the Libyan administration with whom they could engage. While this state of affairs persisted, one could logically only work to address the inflow on the other side of the Mediterranean. However, at this point, few suspected the European Commission would place the compulsory sharing out of the resulting irregular arrivals – a niche concept at best – at the centre of Europe’s crisis response. Sharing out asylum claimants between countries was without precedent; would do nothing to reduce the numbers coming; and was the border control equivalent of putting out the welcome mat to the global smuggling industry.

Arguing the migrants should come in the front door rather than “through the back windows”, Jean-Claude Juncker, the Commission’s president since the previous November, proposed in May the relocation of 40,000 asylum seekers to take pressure off Italy and the other front-line state, Greece 13 . Juncker, an old EU hand and until recently Luxembourg’s prime minister, wanted all Member States to participate based on a ‘distribution key’, a set of technical criteria used by Germany to distribute refugees equitably between the federal republic’s länder. Very much in line with the Commission’s own brand of “technocratic charisma” 14 , the president thought this would be the right symbol of Europe united in the crisis.

The leaders, including Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel, had agreed at the April European Council that relocation from Italy and Greece would be organised on a voluntary basis, where willing states would make pledges of how many migrants they each would take. For Juncker, however, a voluntary scheme totally missed the point that the EU was a family where everyone should pitch in at moments of extremis. His plan for 40,000 relocations was already being mercilessly mocked in the media for its timidity, representing at that time less than a month’s arrivals to Italy. He also sensed the mounting public pressure for Brussels to ‘do something’ meant his proposals had to break new ground i.e. compulsory EU-wide solidarity based on the distribution key. (A concept Tusk told Juncker was an “oxymoron” and which he himself would later concede “can’t be forced…it has to come from the heart” 15 .)

At a late-night European summit in June, both the Commission president and Renzi erupted in righteous fury when several central and east European leaders stubbornly refused to accept mandatory quotas, ever. They were not destination countries for the migrants. If EU membership carried with it the obligation to become multicultural societies, that was news to them. Only member states for a little over ten years at this point, the easterners viewed the Commission’s plan with the utmost suspicion, the thin end of a power-grab into national immigration policies. Rather than clear action to stop the boats, obscurantist Brussels was instead suggesting a bizarre scheme to start sending foreigners into their countries whom they did not want, and who did not want to be there. Furthermore, once the principle that the Berlaymont could start deciding who would migrate where was conceded, where would it all end?

With key actors clearly living in different mental universes, facts on the ground were changing. Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s controversial prime minister and the most virulent opponent of quotas, sent an alarmed letter to both Tusk and Juncker on June 22nd. Huge numbers of migrants were appearing out of the blue in Hungary. Orbán stated his country had registered the highest number of irregular entries in the Union so far that year, and that the Balkan route was now experiencing at least as much pressure as the Mediterranean. Syrians, safe in Turkey but worried about their children’s education, were no longer coming via Libya but instead paying smugglers to get them into Greece direct. Accordingly, numbers were dropping in the central Mediterranean but turbo-charging in the east. By August arrivals to the Greek islands had quintupled with authorities there maintaining a conspicuous silence on what was happening after disembarkation.

Greece was long the weak link in the Schengen area. The country joined the passport-free zone in 2000 and was in theory applying the Dublin rules. But from the first, it exhibited the same “cheating” behaviour that characterised its euro membership. (Brunnermeier et al 2016) Despite the Commission’s prompting, Greece refused to build an asylum system of the kind expected in western countries, reasoning no-one could ask for asylum if there was no one to ask. Like Italy, it regularly waved irregular entrants north to avoid the headache of establishing their status. Fellow Schengen countries struggled to decide whether its seemingly chaotic administration was intentionally malign or incredibly weak. With some of the world’s most pivotal and challenging frontiers to control, Greece’s cynical approach was a major ‘pull factor’.

By the time the boat crisis hit, the Greek state was in no shape whatever to deal with this startling new inflow to the islands. Greece still had no asylum system or adequate holding facilities. Moreover, it was right then already in the middle of a huge economic crisis as a July showdown with creditors ushered in its toughest austerity programme yet. While the Hellenic coastguard did accept help from Frontex with the sea rescues, the Greek authorities would not discuss a plan to get the wider situation in their country under control. That would mean proper registration and screening of the migrants and the end of Tsipras’s policy of ‘waving through’. The Commission thought only the carrot of relocation could entice Athens to start acting responsibly since acceptance of the scheme implied some oversight of Greek asylum procedures. (Later, in October 2015, as the situation spiralled completely out of control, Juncker would belatedly try to toughen up the Commission’s policy, telling Greece and the arriving migrants: “no registration, no rights” 16 .)

Tsipras was not the only one facing unpalatable choices. For over two years now, tens of thousands of migrants every month were making their way up through Italy and the western Balkans to apply for asylum in northern Europe, mainly Germany and Sweden. Angela Merkel, the German chancellor since 2005, was by nature almost pathologically cautious. But she also did her business in the European Council with brutal decisiveness, if the occasion called for it. Her first instinct was Germany, by some distance the Union’s largest recipient of asylum seekers several years running, had already taken enough. The country was at that very moment cracking down on a plague of bogus claims from ethnic Albanians eager to collect the statutory benefits that come with asylum seeker status. Merkel recalled too how, during Europe’s last great migrant crisis in the 1990s, Germany was largely ‘left alone’ to absorb most of the population movements triggered by the violent breakup of the former Yugoslavia into its constituent republics.

On the other hand, the chancellor saw her compatriots’ instinctive desire to help the Syrian refugees. Yes, the huge numbers arriving daily were unsettling. But people were greeting the arrivals at the train stations with food, water, spare clothes and often applause. The spontaneous welcoming of those fleeing war made Germans feel good about their country, a sentiment the burden of history often denied. Never quite able to trust their own instincts, they now looked to the figure affectionately nicknamed ‘Mutti’ (Mummy) to define how the nation should see the situation. Merkel tried to think how Germany would look back on the episode in 50 years’ time. Then she stared into the unknown and chose Sondermoral (special morality), a super-charged form of the ethic of conviction. Towards the end of August, she told Germany: “Wir schaffen das”: ‘We will make it’, in the sense: ‘We will come through to win in the end’. However high-minded, Merkel’s decision was also certainly influenced by internal advice stating there were no legally sound options for ending the mass arrivals.

Historians will debate the chancellor’s utterance, intended for the German public and to buy time, years hence. There is no doubt her statement was re-watched avidly on smartphones and TV sets in tents and tea shops across Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Iraq, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Syria itself. Millions of desperate people – poor or not, in danger or not, Middle Eastern or not – interpreted it as an announcement Europe was open; an explicit vocalisation by its most powerful leader of an invitation previously only suspected, hoped for or inferred. Smugglers pounced on it as a propaganda coup. Merkel then went further and suspended Dublin’s first-country-of-arrival rule, clearing a path to Germany for those Syrians making the journey. (Sondermoral took precedence over the rule of law here.) Arguably, this merely recognised reality and the flows were going to spike anyway. But the chancellor will forever be associated with the all-time highs the influx subsequently reached, with 10,000 people per day walking across the external border, and strange scenes such as groups of Afghans attempting to bicycle into Europe from Russia. Two weeks after her announcement, on September 14th, Germany became the first country in the crisis to re-introduce national border controls within Schengen. The moment of positivity over, Merkel’s innate caution had reasserted itself. Like Renzi and Mare Nostrum, now she needed an out.

At first though, the chancellor seemed to have read the political runes right as ever. September 2nd saw shocking television images of the body of Alan Kurdi, a three-year-old Syrian boy, innocent and perfect as any sleeping toddler, washed up on a Turkish beach, face down into the Aegean. Riding a universal outpouring of grief, Juncker now tabled the mandatory relocation of 120,000 asylum seekers over two years, on top of the original 40,000. Merkel backed Juncker fully, delivering all the moderate Member States to the Commission. On September 22nd, Luxembourg – then serving as the EU’s rotating ministerial presidency – controversially forced the question to a vote of interior ministers, pushing the scheme through over the objections of Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia and Romania. Poland voted in favour but its Civic Platform government – led by Tusk for seven years before he became European Council president – was beaten in elections the following month by radical nationalists who immediately reversed course. (Finland – a country which would vacillate between pro- and anti-relocation stances – abstained.)

After the vote, seasoned officials who thought temporary relocation at most a useless distraction now felt a guilty sense of relief. At least, they hoped, the bitterness and moral posturing might be over with and Member States could finally get down to a serious conversation on ending the crisis. However, an emergency European Council the next day was much too soon for any catharsis, as Tusk wryly noted in his pre-summit statement “nobody will be out-voted”. (European Council 2015b) The east Europeans affected wounded dignity, maintaining they would challenge the relocation decision in court on the grounds Brussels had no right to decide for them who could enter their countries. As for the ongoing crisis, the summit heard there were over 2 million Syrians in Turkey and around 1 million each in Jordan and Lebanon, as well as another 4 million internally displaced inside Syria itself. The Syrians were moving because conditions in Jordan and Lebanon were worsening and because those in Turkey wanted a better future for their children. Donor fatigue with the Syrian conflict in 2014 meant the international agencies trying to address its humanitarian fall-out had had their funding cut. This short-sightedness accelerated the subsequent massive population movements. Accordingly, the leaders agreed to mobilise immediately an extra €1 billion to feed the refugees along the route through the World Food Programme (European Council 2005c) and increase UNHCR’s capacity to assist Jordan and Lebanon to stabilise their displaced populations.

This gentle, herbivorous summit outcome concealed the fact EU leaders, urged on by Tusk and others, were at last starting to move on border protection. High-level visits were scheduled with the western Balkan countries, Greece and Turkey, all of which received multiple embassies that autumn from concerned EU countries; Juncker’s deputy, Frans Timmermans; and Tusk himself. North Macedonia was the key. Only if it could close its border with Greece would migrants, smugglers, front-line countries and neighbours alike all get the message the Europeans really had had enough. The North Macedonians and neighbouring Serbs now rushed to leverage a brief moment of political advantage before a border closure somewhere along the route shut their window of opportunity.

Turkey, the world’s largest refugee hosting state, was in a strong position. It shared a border with Syria and had performed the impressive feat of settling over 2 million Syrians on its territory, blending the generosity of a developed country with the flexibility of a developing one. (Betts & Collier 2017: 3, pp.76-86) 17 . Contrary to popular belief, refugees are not entitled to enter any country they wish. The unique right that goes with their status is non-refoulement: not to be sent back into danger. Under this definition, Turkey was safe and that meant there was a negotiation to be done. Ahmet Davutoğlu, Turkey’s then prime minister, knew this. He waited for the European side to bring proposals, firing off rhetorical salvos to play on his counterparts’ nerves, including having interior minister Süleyman Soylu threaten to “blow Europe’s mind” by sending 15,000 irregular migrants per day across the border 18 .

In fact, the Commission’s technocrats were already busy preparing a package whereby Turkey would receive a walloping €3 billion to feed and educate its Syrian population. The EU would additionally resume negotiations on Turkey’s stalled accession talks and facilitate greater access to the Schengen area for its citizens. At a meeting en marge of the G20 in November, Tusk and Juncker together endured a gloating Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey’s president, delivering a high-handed dressing down later leaked to a little known news website. This led Tusk to argue it was important to send the signal Europe was not completely desperate, otherwise the Turks would overplay their hand. With the Greeks still stonewalling, the idea of a coordinated border closure from Austria to North Macedonia was born. Tusk, who knew the Balkan countries well and could speak their languages, toured the region in October and was told by leaders there “not a mosquito will pass” 19 , if the Europeans gave a clear instruction and provided aid. Greece, realising the game was finally up, now made a formal request for EU intervention that December, hoping to benefit from relocation ex post for the 60,000 migrants still present on its territory with thousands more arriving every day in winter weather.

The Balkan border closure was timed for the traditional informal European Council at the end of February 2016. Tusk put forward conclusions calling for “an end to the wave-through approach”. (European Council 2016: 8d) Nestled in paragraph two of the summit communique, the long-awaited instruction was now transmitted, and well received. A few days later the Balkan route began to shut down and arrivals started falling sharply: from 70,000 in January 2016 to 30,000 in March. But now there was a difference of opinion amongst the Europeans over what to do about the Syrians who still accounted for between 30-50 per cent of arrivals. Tusk thought since they were safe in Turkey, the Syrians’ attempts to come to Europe en masse could be halted in good conscience. They were not fleeing war directly and hence were irregular economic migrants, not asylum seekers. In Athens on March 3rd, Tusk finally made the statement he had wanted to make a year previously: “Do not come to Europe. Do not believe the smugglers. Do not risk your lives and your money. It is all for nothing.” (Rankin 2016)

The Balkan route was closed. But only an understanding with Turkey could definitively end the crisis. Meanwhile Willkommenskultur in Germany was evaporating after New Year celebrations across the country were marred by seemingly spontaneous mass outbreaks of sexual violence by men of Middle Eastern and North African background. Politically on the back-foot now, Merkel could not afford the Turks walking away. Newly advised by senior interior official Jan Hecker, she was out of patience with Brussels institutions she despaired of as too flaccid and cerebral to deliver. At the last minute, the chancellor and her ally Mark Rutte, the Dutch prime minister, went all in. On the eve of an meeting in Brussels to sign off an almost done EU-Turkey deal on preventing fresh departures from Turkish shores, Rutte unilaterally offered Davutoğlu double the financial settlement (€6 billion), and also an additional refugee swap whereby ‘Europe’ would resettle one Syrian for every asylum seeker sent back to Turkey from the Greek islands 20 . (A cumbersome idea invented to circumvent reservations some Member States had about turning back actual refugees, even those transiting through safe countries.) The delighted Turks happily agreed to present the augmented plan as their own. Blind-sided and worried by a precedent that might inspire others to blackmail the EU, Tusk had to play up since the offer could not be unmade without risking the original deal. The other leaders were furious. Merkel and Rutte had secretly conceded better conditions to Turkey behind their backs. J W Beaujean, Hecker’s Dutch counterpart and co-conspirator, would later unapologetically describe the move as “disruptive innovation”.

Tusk soothed the leaders while his senior officials hammered out an agreement with the Commission on how Greece would be helped to administer the deal, including hundreds of EU guest officers to assist with screening and returns from the islands. UNHCR and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) were shanghaied in at the last moment to assist the Greek authorities, a job they instinctively disliked because the new arrangements seemed to undermine the hallowed principle of territorial asylum. UNHCR retaliated by ensuring asylum procedures on the islands included a two-tier appeals process that completely contradicted the original intention to use ‘accelerated processing’ to winnow out inadmissible claims. Nonetheless, on March 18th Davutoğlu signed off on the ‘EU-Turkey Statement’. (European Council 2016b) In April, arrivals slumped to 4,000 for the entire month. The acute phase of the crisis was over.

Europe breathed easy for the first time in months. But boat arrivals to and ‘secondary movements’ from Italy (i.e. to other EU countries) were still ongoing. These were never remotely as high as on the western Balkan route and a lot less morally complex because – contrary to popular perception – Syrians did not return to Libya after 2015 21 . The vast majority of central Mediterranean arrivals were west African economic migrants. After numbers rose again sharply in late 2016, EU leaders met again in Malta the following February. Things were now not as grim as the previous April. Libya had a semblance of centralised authority under a new Government of National Accord. It transpired the Libyan national coastguard still functioned despite the conflict. And better intelligence revealed the mass departures were taking place only from a small sliver of the Libyan coast, closest to Tunisia, around the cities of Zuwara and Sabratha.

The parameters were promising. However, the real game-changer was Italy’s wily interior minister, Marco Minniti. The former intelligence chief and ex-Eurocommunist knew the internal politics of Libya’s tribes like the back of his hand. Quoting Deng Xiaoping 22 , Minniti struck with a deal with the Libyan coastal municipalities whereby they would reject the people smugglers in return for wide-ranging aid. He also began requiring the NGOs to follow a code of conduct. Some acted less like humanitarians and more like vigilantes: forcing confrontations with the authorities, trolling them in the media, and implicitly co-operating with the smugglers. In any event, the EU agreed to fund and help administer the municipalities deal and, in return for halting the irregular departures, also to train and equip the Libyan coastguard. As a result, monthly interceptions fell below 5,000 by August 2017 and stayed there.

Analysing Europe’s response

“One year ago, at the outset of the migration crisis, some accepted as a given that the migration wave is too big to stop. One consequence of this was to suspend the Schengen and Dublin rules, leading to the opening up of our territory to uncontrolled migration. Stopping this dangerous trend was a change of paradigm. So, several months ago, I proposed we make the reverse assumption, that the wave of migration is too big not to stop. Our priority should be to have a proper migration policy. The European Union and its member states must regain the capacity to decide who crosses our borders, where and when.” Donald Tusk, April 22nd 2016, Der Spiegel.

The battle for Europe’s response to the border crisis was mostly a contest between integrationist doves and realist hawks. Each camp had its own spectrum, from moderates to hard-liners, who would provoke and energise opponents on other side: ‘small c’ conservatives versus liberal internationalists; nativists versus one-worlders. The hawks mainly comprised Tusk, Austria (after 2016), Denmark, the Baltics, the so-called V4 23 countries; Slovenia, practically all the interior ministries and a smattering of no-nonsense officials across the EU institutions, including in the Commission’s home affairs directorate 24 .

Long a critic of Schengen’s porous external frontier, France was certainly a hawk at heart. In November 2015, French prime minister, Manuel Valls, openly questioned Merkel’s policy, grumbling “it was not France who said “Come””. But because of France’s need to stay close to Germany in hopes of getting agreement on a new economic paradigm for the Eurozone, its socialist government maintained a sphinx-like inscrutability thereafter. Likewise, Spain, although formally with the doves, was also a hawk-at-heart, or a neutral, since it never really believed in relocation as the answer to migratory pressures, and relied on special arrangements with west African countries and Morocco to prevent boat departures.

What is often not well understood is the disagreements between the hawks and doves were as much about sequencing and style as substance. In the hawkish worldview, Schengen and Dublin were designed to be functioning border control systems that effectively compensated for the lost protection of the old national frontiers, not reverse engineered to distribute asylum seekers or salve progressive consciences in Brussels. Furthermore, the self-seeding nature of the boat phenomenon meant the Union’s communication had to be crystal clear: Europe would not tolerate spontaneous mass arrivals; therefore, the boats were not welcome. In the age of digital mass communications, the message had to be that stark otherwise the crisis would never end. Meanwhile, sotto voce, the Europeans would increase large-scale humanitarian and development assistance to help the refugees, continue resettlement from conflict zones and hope the rest of the world would wake up and lend a hand. Tusk tried to push the latter point up the international agenda at the 2015 UN General Assembly, characterising the Syrian refugee question a “crisis of global dimensions”. The plea was greeted with a deafening silence by the international community with the oil-rich Gulf states, for instance, conspicuous by their refusal to take in or help the Syrians.

The doves, led by Germany, Sweden and the Commission leadership; and urged on by the European Parliament, the UN Refugee Agency and Europe’s foreign policy establishment, considered such an approach antithetical to the Union’s identity and values as a peace project. The humanitarian message should be the dominant one, and this translated into relocation as the flagship policy. Meanwhile, it was the efforts to control the external border, distasteful though necessary, that should be sotto voce. Given the legitimacy of the European project rests greatly on its soft power (the power of attraction rather than the attraction of power), this was a perfectly solid analysis. Where it fell apart was the overwhelmingly sympathetic and positive political messaging would, of course, continue being interpreted by smugglers and the migrants as: “Come”.

Whereas the hawks were practical and pessimistic, unimpressed by gesture politics and instinctively turned off by grand visions, the doves were enflamed with a can-do optimism and determined to commandeer the EU structures in pursuit of progressive ideals. Moderate hawks genuinely feared the chaos could collapse the EU by propelling Eurosceptic extremists to power, as then seemed entirely possible, in elections in France and the Netherlands the following year; or send the rest of central and eastern Europe the way of Poland and Hungary. Then, as if tensions were not high enough, it was revealed that at least two Islamic State terrorists, who helped kill 130 people in Paris on November 13th 2015, had entered Europe through Leros posing as refugees. (Speaking to a rally of far-right parties in Koblenz, Germany, Marine Le Pen would chillingly draw on such events to declare the end of liberal democracy: “their world is ending, ours is beginning”.) The doves were adamant, no matter what happened, they simply would never mimic the populists with unwelcoming language towards asylum seekers. Instead, they wanted to focus on building up reception capacity in the reluctant Balkan route countries — Rubb halls, one-night accommodation and so forth — to try to slow the inflow and make it more orderly and manageable.

Hawks lived in dread of amateurish statements and well-meaning virtue signalling from a plethora of EU figures in Brussels who still, even late in the day, did not “get” the febrile situation. Ironically, the moderate hawks focused most on communicating externally: to the migrants, smugglers and the foreign powers trying to manipulate the emergency to fatally weaken the EU; whereas the internationalist doves looked inward, seeking to convert the European public to a brave new era of global migration they considered inevitable. The east Europeans in particular hated this ‘inevitably’ argument almost as much as they hated the Commission’s pretentions to organise the movement of migrant populations around the continent. They grimly compared that kind of language and centralising urge to the totalitarian communist regimes they lived under for 40 years. Had they re-joined Europe only to be dragged back into utopian dreams, this time by a bunch of middle class kids in Brussels? In their experience, political dogmas wrapped in the brotherhood of man swiftly turned to nightmares.

Doves did not think or speak about pull factors, people smugglers or boat people. They saw the whole episode exclusively in straightforward humanitarian terms and as a make-or-break moment for Europe’s reputation as a progressive standard bearer. They bought into the notion of collective European guilt for colonialism — a sentiment alien to the easterners — and argued the boats and their occupants were an answer to the continent’s declining demographics. (In one sense, they had a point here: around 100,000 Syrian children are born in Turkey each year due to its huge refugee population, adding a million to the population in a decade.) It is absolutely vital to understand the European Commission is also a major global humanitarian actor, with a track record stretching back to the late 1950s after the creation of the European Development Fund alongside the European communities. By contrast, the Commission in 2015 only had true stewardship of the Schengen system for just a few years, following a shake-up of the passport-free zone’s evaluation rules in 2011. This unbalanced pedigree greatly informed its gut instincts in the emergency; and explains why the Berlaymont was much more comfortable putting its energies into coordinating humanitarian efforts in Greece and the Balkans as well as trying to find ad hoc solutions for those rescued in the central Mediterranean.

Above all, the doves wanted to be on “the right side of history”, a phrase much in use at the time. The same argument could be heard often from the European Parliament’s powerful civil liberties (LIBE) committee, which had an uncompromising position on relocation and tried hard in March 2017 to force governments to issue humanitarian visas to anyone from the Middle East wishing to apply for asylum in Europe. The problem here was a policy change like that with major ramifications for European societies had next to no bearing on the re-election prospects of MEPs in May 2019. Voters were completely in the dark as to what the Parliament was doing.

Doves thought the continent too closed, with no legal pathways for immigrants to enter. Hawks, new initiates to the managed hypocrisies of Schengen and Dublin, were shocked to learn their countries apparently had no effective border with Afghanistan, Iraq or Syria. To the hawks, Europe was a shared territory to be cherished and protected, indeed this was what chiefly defined it as a political community. To the doves, Europe was a beacon of universal values that at all costs must not be gainsaid. For the hawks, European values meant ‘open borders for Europeans’; for the doves: ‘open borders for everyone’. (This internal dispute about the fundamental nature of the EU – one more republican, the other universalist – is mirrored in other areas, including foreign policy and European constitutional law.) Both were sure subsequent events would vindicate them. Both were in no doubt theirs was the only responsible, realistic and pro-European stance.

Angela Merkel triangulated brilliantly between these two mental landscapes. Unwittingly, she had become the face of the liberal West in a rapidly darkening world, fêted by the international media and declared Time magazine’s 2015 ‘person of the year’ for her pro-refugee stance. At the same time, she was manoeuvring to end the flows via an EU agreement with Turkey, for which the Union would take the flak from liberal opinion for a ‘dirty deal’. For a while she was untouchable. Then New Year 2016 killed the feel-good factor. These strange, disturbing events inspired Schadenfreude in those who felt Merkel’s approach at best sadly naïve, or at worst ‘Birkenstock imperialism’, preaching humanity that magically co-aligned with German interests.

Merkel repeatedly made the optically shrewd argument that she could not understand how a well-off continent of 500 million people could not take in and share out 1 million Syrians. But this cloaked the reality, including that the operational problems with relocation were legion and also, even if perfectly implemented, that relocation alone would not actually reduce migration pressures on front-line countries: by itself, it was another pull factor to their borders. (The dovish school of opinion disagrees, thinking relocation to a country different from the intended destination undermines the business model of the people smugglers, and therefore represents a form of border control in conformity with humanitarian ideals.)

Allocating undocumented nationals between different administrations is a few words on paper. Setting up efficient screening processes in Greece and Italy to make it happen was another thing entirely. The length of the asylum procedure coupled with sluggish Mediterranean legal systems meant the scheme could not work with refugees whose stories had been verified, as UN resettlement does, but only those claiming to be refugees. Asylum claimants routinely destroy their identity documents on arrival, to make it hard for authorities to establish their status or return them to the country of origin. EU countries would have to take candidates on trust and do the procedure at home. This led to lengthy delays and backroom standoffs as Member States wanted to be as certain as possible before accepting people who might be security threats or were not the nationality stated.

The UN Refugee Agency strongly advocated the introduction of mandatory quotas into Europe. With over 70 million displaced people globally 25 , the Geneva-based agency was desperate to expand the number of resettlement places available worldwide. It looked on the relatively well-off and stable EU, where it had the ready ear of the Commission; and where half the Member States were barely refugee-receiving states at all, as low-hanging fruit. Even so UNHCR counselled the Berlaymont to beware. Despite a clear mandate, 70 years of accumulated expertise and a global network, the agency only managed to resettle around 100,000 bone fide refugees per year from conflict zones. It was extremely unlikely the inexperienced Commission could organise an entire new system from scratch during an ongoing crisis and move 160,000 candidates in two years. Predictably, only an embarrassing handful were transferred in the first six months, and two years later only 20 per cent were relocated. More importantly, few if any beneficiaries stayed in their allocated countries regardless of whether the host was Portugal, Lithuania or Luxembourg. Almost all quickly again ‘self-relocated’ to join existing migrant networks in their preferred destinations, usually Germany or Sweden. The whole exercise seemed ill-fated, a cautionary tale of “technocratic overreach”. (van Middelaar 2018: 3, p.100)

Nevertheless, the Commission dubiously declared the temporary scheme a success and not only to save face. The crisis laid bare Dublin’s dysfunctionality for all to see. Several countries had re-imposed national border controls within Schengen and now refused to raise them. The Commission wanted to respond by rebooting the common asylum system according to a grand new design. At its heart would be a recast Dublin regulation, incorporating — to the barely articulate rage of the V4 — a permanent, mandatory relocation element. In fact, the Commission was proposing a quid pro quo: systematic quotas for front-line countries in return for their explicit, legal acceptance for the first time to be the border guards of Europe. The latter would be expressed in bureaucratic terms by extending Member State responsibility for screening first arrivals from a year to ten years, i.e. an asylum seeker who enters in Italy and is later detected in Norway could be sent back for adjudication by Italian courts up to ten years later, and vice versa 26 . In addition, procedures at the external border to establish immigration status would now be mandatory, preferably for every irregular entrant without exception.

The Commission’s plan had its points but the timing was awful. The wounds of the crisis were red raw and trust sub-zero. One after another, every compromise text tabled by various Council presidencies between May 2016 and 2019 was shot down, no matter how subtle or elaborate. Even if Member States in the Council had been able to come to an agreed position, the European Parliament was waiting in the wings to impose a radical alternative vision in the second round of negotiations which would make the Commission’s original “look like a V4 proposal”, in the words of its senior officials. The parliament’s futuristic vision for permanent relocation was considered science fiction even by Sweden, the EU’s liberal lion on refugee issues.

Politically, rewarding countries with permanent quotas after 20 years of rule-breaking within Schengen was like Germany offering to issue government bonds jointly with Greece and Italy without any prior economic reform 27 . Where was the guarantee quotas-for-checks would ever really end the moral hazard at the external border? The Netherlands for one wanted to believe it would work. The Dutch government had pushed hard in 2016 to convert Frontex into a fledgling European Border and Coast Guard, and was that rare breed: an integrationist hawk. (So too was Bulgaria, a non-Schengen EU Member State which had a very tough border policy but also considered relocation strongly in its interests.)

The Dutch actually saw the quotas as a way to impose discipline on the border countries. Italy and Greece would often accuse ‘Europe’ of abandoning them, no matter how many millions in aid Brussels sent south to fund their border and asylum services. Now the transparency of the proposed new system would take away their ability to play the victim in public whilst simultaneously waving arriving irregulars north. And the southerners would finally have to confront an unpalatable issue they had tried to dodge ever since becoming Schengen countries: the job of detaining the many asylum applicants who abscond before a decision is made on their status. With the same vehemence the easterners could summon for quotas, the Italians in particular were adamant: they would never build a “parallel penitentiary system” in their country for irregular migrants, no matter how much the Commission and the northern countries insisted some form of detention was necessary to prevent secondary movements. Here it should be noted, even according to UNHCR, the vast majority of irregular arrivals in the central Mediterranean would not qualify for asylum status. Hence the Italians in particular were terrified they would have to lock up thousands of failed asylum claimants for long periods whilst being unable to deport them.

The long-time contention of the northern Europeans was if Mediterranean Schengen countries would only toughen up asylum procedures at their borders, including via detention, then that would end the irregular boat arrivals once and for all, albeit after a difficult settling in period. For the Netherlands, this was securing the external border using the ‘right’ (i.e. rule of law, not blood-and-soil) arguments. The Dutch thought, perhaps a bit naively, the Mediterranean countries should just adopt their own ultra-efficient system for screening asylum seekers in a few days or weeks. At the same time, the east Europeans should be made to see that the benefits of Schengen did not come for free. Their stubborn insistence that this was not their crisis was perceived as yet another symptom of an illiberal drift that needed confronting. Reading between the lines, this was now also the position of France after Emmanuel Macron came to power with La République En Marche! in May 2017.

The eastern countries could see all this, of course. What they could not see was why they, frontier states which had never posed a problem for the smooth operation of the Schengen area, should pay the price for the Commission’s failure to enforce the rules in Italy and Greece, nor why they should be forced to become multicultural societies by smug western Europeans who could barely integrate their own first and second generations of migrants. And they had no doubt whatever that, because it could not even occasionally bring itself to speak the language of control, the dovish Commission would never enforce the enhanced responsibility aspects of a new Dublin system on the southern countries. Instead, its focus would always be relocation, relocation, relocation.

As if on cue the Italians began arguing, highly inconveniently but coherently, it was no fault of theirs international law and European jurisprudence obliged them to rescue people at sea. They found it supremely unfair that the (often German-funded) NGOs would continue bringing tens of thousands of irregular migrants into their ports whilst Berlin insisted, under the Dublin rules, that Rome must then take back any asylum seekers who subsequently managed to reach Germany. Now Italy wanted all irregular maritime arrivals, asylum seekers or not, to be exempted from the first-country-of-arrival rule and automatically shared out around the EU before the border procedure. The country had finally articulated its revenge for the implications of the Hirsi ruling.

In mid-2017, caretaker prime minister Paolo Gentiloni made clear to Tusk that Italy had more to lose by accepting greater responsibility for border procedures (which implied official registration as an asylum seeker on Italian territory) than it had to gain through permanent relocation. Italy then formed an unlikely alliance of convenience with the front-line eastern EU states to block the Commission’s proposed ten-year responsibility period. This led Tusk to conclude that he would not risk a divisive discussion on the EU’s asylum rules at leader level so long as no proposal existed that could deliver the Italians whilst securing the external border without creating further pull factors.

Meanwhile, Greece’s woeful mismanagement of the Turkey deal raised serious questions whether it could ever really be a functioning part of Dublin. Despite thousands of guest officers from other Schengen countries and a wholesale reform of the Greek asylum system in 2018, the refugee swap was an undoubted failure with practically no forced returns of Syrians to Turkey 28 . Furthermore, despite over two billion euros in EU aid, the Greeks either could not or would not ensure reception facilities on the islands were basically adequate — failing even to winterise the asylum seekers’ tents against cold weather. Instead they resorted to emptying the camps periodically by transferring the most desperate cases to the mainland: another pull factor that would entrench the crisis there for a further four years. The only reliable Greek service seemed to be the army, which would be called in from time to time, to build emergency infrastructure.

Within the EU institutions, where too many considered the strain on national politicians as having little to do with them, the intellectual journey was gradual and went like this: ‘Should we stop the flows?’ to ‘Can we stop the flows?’ to ‘How do we stop the flows?’ Each such shift was opposed stoutly by the European Parliament and the Commission’s formidable humanitarian and development aid wing — which, to the exasperation of the hawks, controlled almost all the relevant European funding, the one EU asset that if used rightly could make a vital contribution — as well as senior EU foreign policy officials. These were backed up by a clique of progressive NGOs, pro-asylum advocacy groups 29 and international organisations that, although receiving most of their funding from the Union, would not hesitate to drag its name through the mud publicly or undermine privately any attempts at controlling the situation they opposed from an ideological standpoint 30 . Not even the administration of Donald Trump came in for the vehement criticism such actors would call down on Europe’s head, despite Trump’s very harsh border detention policy and gleeful slashing of US resettlement quotas down to nothing. Meanwhile the EU was pilloried, even as it backstopped the entire global humanitarian system 31 .

Likewise, Canada – which would not for one minute entertain the kind of mass maritime arrivals Europe had endured for several years – was praised to the skies for its fast-track resettlement of 40,000 Syrians in 2016, whilst the Europeans receiving hundreds of thousands of asylum claims per month were treated as a disgrace. (EU recognition rates for the Syrian asylum seekers were around 90 per cent.) The chief obsession of the international agencies was to oppose anything smacking of a move by Europe towards ‘external processing’: determining refugee status in special centres outside the EU whilst preventing irregular arrivals altogether. Austria and Denmark in particular sought to proselytise such a radical shake-up as the only effective and far-sighted Dublin reform, citing Europe’s geographic vulnerability and the open, systematic abuse by irregular economic migrants of the right to apply for asylum, purely as a means to cross the border.

Europe’s bevy of doves was not to be taken lightly. It often acted in concert and with an overbearing moral certainty, forming a humanitarian-internationalist complex within and around the EU institutions that had zero interest in the integrity of Schengen or stopping the boats. On the contrary, they believed passionately that the migrant inflow per se was neither a threat nor a problem, but Europe’s legal responsibility and humanitarian obligation. Doves had a Panglossian view of migration, irregular or otherwise; believed the politicians could re-frame public perceptions of the crisis by cutting out the water metaphors in their rhetoric; and thought that Europe could easily handle the arrivals if it would only rise to the occasion and “get organised”, a regular euphemism of Filippo Grandi, the UN refugee chief, for relocation. (Grandi 2016) However, none of these actors would be the ones with the job of convincing European voters, east or west, to accept ongoing mass arrivals; force relocated asylum seekers to stay where they were; or make the other Schengen states raise their border controls as Greece waved through. And not one would explain why Europe was the only place in the world which should tolerate a boat crisis phenomenon in perpetuity.

How small states fared

For smaller states, the border crisis was defined either regionally or strategically. The former dictated if they were exposed directly to the irregular arrivals or solely to the implications of Europe’s churning politics. North Macedonia’s case deserves elaboration. With circus-like internal politics, shifty neighbours and a weak administration (the population is 2 million), the country experienced a moment of intense vulnerability in August 2015 when its authorities were simply pushed aside by the overwhelming numbers of irregulars. Added to this, relations with Greece were almost non-existent due to the 30-year dispute between the two countries over ownership of the name ‘Macedonia’. However, North Macedonia’s location made it pivotal to closing the Balkan route. Throughout 2015 and 2016, it was unblushing in haggling for assistance from the EU to re-man its border. As a result, a multinational mission made up of personnel from the region and the V4 countries was dispatched there and the country received €10 million to buy surveillance equipment and patrol vehicles.

Relations with Greece might have been expected to sink even lower. Indeed, EU officials in rolled-up shirt sleeves were driven to face-palming themselves out of frustration in November 2015 when Greek diplomats refused even to sit in the same room as the North Macedonians during a crunch meeting at the height of the crisis. It came as a surprise to most, then, that the decades-long name dispute was resolved not long after the border crisis ended. It is arguable, even likely, that the migrant episode underlined to Greece the strategic importance of normalising relations with its neighbour. (Next door Bulgaria, for example, never once acted against Greek interests throughout the entire emergency despite their shared frontier.) Whatever the reason, North Macedonian fortunes took a huge step forward as a result, since Greece lifted its veto over its accession talks with the European Union and NATO membership.

As regards small EU Member States, Malta and Slovakia make good case studies because one strongly favoured permanent mandatory relocation and the other strongly opposed it. Both were tasked with finding a diplomatic solution to the apparently unbridgeable divide between the Member States on reforming the Dublin regulation in successive stints as the EU’s rotating ministerial presidency during the second half of 2016 and first half of 2017. Although massively self-interested in the outcome, both managed to convince as reasonably honest brokers. The Slovak presidency introduced the concept of ‘flexible solidarity’, or the idea that countries which did not wish to take people might show their solidarity in other ways, such as border guards, asylum screeners, equipment or money. The concept stuck, even if the Slovaks failed to find a successful formula for its application, as perhaps no Council presidency ever will. Despite the rambunctious behaviour of Prime Minister Robert Fico, Slovakia emerged from the crisis with a reputation as the most moderate of the V4, taking a handful of asylum seekers from Greece and Italy for form’s sake without changing its position on relocation or incurring the wrath of the other V4. (Only Poland and Hungary took none as a matter of principle.) With Germany and other net contributors seeking to link future EU budget transfers to the refugee question, Slovakia’s discrete tango between principle and pragmatism might one day matter a lot to the nation’s bottom line.

Malta was by far the most vulnerable country in the crisis. The small state lies very close to Lampedusa and has a population of half a million people. Because of its location, its SAR patrol area is out of all proportion to its size, an inheritance from the country’s 150 years as a British dependency. Even the arrival of a few hundred migrants per week could potentially wreck the nation’s major industry: tourism. This never happened, despite the largest irregular flows ever crossing the central Mediterranean, right past Malta, for over three years. Neither country will confirm it, but an informal agreement to share SAR responsibilities clearly existed between the Maltese and the Italians from at least the time Mare Nostrum was launched. Malta was historically hostile to Italy patrolling in its SAR area for sovereignty reasons. This hard-line stance was relaxed when it was agreed the rescued would be taken back to Italian ports. It is very difficult to see how Italy benefitted. Rumours abound about a quid pro quo on energy exploration rights in the SAR area, but these have never been substantiated. It is entirely possible that any putative arrangement simply recognised the obvious: Malta could not sustainably accept disembarkations on any scale.

Prime Minister Joseph Muscat and Malta’s tough, well-liked EU ambassador, Marlene Bonnici, ensured the country played a strong role in shaping the Union’s crisis response. Muscat pushed to host a rare EU summit with the African Union in November 2015 aimed at creating a new multilateral partnership on migration and development with the Africans, including on the highly delicate issue of returning irregular entrants home. Largely a brainchild of Pierre Vimont, a former head of both the French and EU diplomatic services nominated by Tusk to handle the negotiations, the resulting Valletta declaration and action plan were at the time under-appreciated. However, it remains the only multi-regional accord of its kind on migration and crucially agreed on the setting up of a €1 billion Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, a critical innovation allowing the EU to scale up cooperation in key areas with African administrations over the next two years.

Bonnici chaired both the EU’s crisis coordination committee, the so-called Integrated Political Crisis Response mechanism, and Coreper, the Council’s most senior decision-making body at diplomatic level in early 2017. Malta also hosted the EU summit in February 2017, where the operational steps to halt the central Mediterranean flows were decided. In short, the country sheltered under the wing of its larger neighbour to protect itself and its economy, whilst leveraging its EU membership to the absolute maximum throughout the crisis.

Whether they agreed with relocation or not, smaller countries understood its totemic status. If they were not directly affected by the flows, there was little chance of creating a pull factor by participating. On the other hand, if they did not play up, they would incur the ever-lasting ire of the Brussels establishment and the so-called like-minded states: Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and others, which were heavily invested, emotionally as well as politically, in a ‘European solution’ on burden-sharing as a kind of catharsis. Small countries were eligible for relatively small quotas under the distribution key’s criteria, even if international rules on family reunification meant that to accept one person would in reality mean five or six eventually being resettled. Still it made sense for them to play along. Hence most band-wagoned. (Walt 1987).

The Baltic countries did so too, despite being every bit as opposed to relocation as the V4. Dalia Grybauskaite, Lithuania’s formidable president, elicited an actual scream from Matteo Renzi at the June 2015 European Council, stating bluntly her country would demonstrate solidarity to others “but not with a gun to my head”. In other words, solidarity demanded with menaces of political isolation was really thinly disguised coercion. Grybauskaite verbalised the unease of many in the room at the unnerving direction European politics seemed to be taking. This played particularly on the insecurities of the central and east Europeans, still doubtful they were truly seen as equals around the EU table. (Eastern Europe is rife with widely believed rumours, for example, that despite European harmonisation, western members of the single market send inferior versions of consumer goods and products like Nutella to the former Ostbloc.) Now the easterners saw their acquiescence to relocation being taken for granted by the Commission and the older EU members.

Nevertheless, rather than play the sovereignty card like the V4 had, and knowing full well the arrivals would never stay, the three Baltics took in several hundred asylum seekers and, despite pushback from their own voters, made sure they were properly treated. When the newcomers left, their hosts were blameless. Facing the daily threat of a revanchist Russia which annexed Crimea only the year before, the Baltics could simply not afford to fall foul of a European establishment they themselves might urgently need to call on for help. It should be noted, however, that relocation did push Estonian politics to extremes with the far-right EKRE party entering coalition government in 2019, largely on the back of this issue.

One out-rider is Denmark, where immigration remains one of the defining issues in politics after well over a decade. Due to their special constitutional position in the EU, the Danes were able quietly to opt-out of relocation (as did Britain under a similar arrangement) without any reputational damage. Unlike its neighbour Sweden, which received proportionately even more arrivals than Germany, Denmark — though granting temporary asylum to 30,000 Syrians since the outbreak of the war — discouraged further arrivals through tough policies which included confiscating the asylum seekers’ belongings to pay for their processing and upkeep. Again, the Danes never really attracted criticism from the normative EU states or the European Commission for this. Like fellow Nordic countries, Norway and Iceland, Denmark contributed to EU-flagged SAR operations in the Mediterranean and to the screening efforts in the Greek islands. This was the minimum price-tag for respectability in the crisis. Denmark hid, in other words.

Ireland and Cyprus are another two cases where seeking strategic shelter came into play. Like all island states, Ireland was traditionally cautious on refugee resettlement. But Ireland’s government increasingly viewed Germany’s support as pivotal in securing the EU27’s commitment to prevent a hard border with Northern Ireland as one of its red lines in the Brexit negotiations. It therefore cheerfully exceeded its migrant quota of 600 people under the distribution key. Cyprus also cooperated, albeit not as enthusiastically, owing to its need for the Union’s full solidarity in its active territorial dispute with Turkey. But then Cypriot national interests got awkwardly entangled with diplomatic manoeuvres to secure the EU-Turkey Statement. Turkey mischievously demanded the opening of the very EU accession chapters blocked by Cyprus as part of their territorial dispute in the north of the island. President Nicos Anastasiades was careful to extract prior guarantees that any deal would not sell out fundamental Cypriot interests, stating just before the key EU-Turkey summit in March 2016: “We are saying yes to Europe, and no to Turkey.” The wheeze worked. Turkish accession would not move forward anyway for other reasons.

Luxembourg is probably the most influential small state in Europe (if not the world) and as ideologically pro-migrant as the V4 were against. A rare example of a nation seemingly comprised of middle class liberals, Luxembourgers saw a total equivalence between progressive ideals, openness to immigration and pro-Europeanism. Deportation, detention, building fences and holding camps: these things belonged to the darkest chapters of Europe’s past, the very inhumanity the Union was created to guard against. If Europe did not demonstratively keep to the virtuous path, especially when it seemed hardest; if people like Orbán and Kaczyński started winning the big arguments, then European integration might well go into reverse. Luxembourg backed German Sondermoral one thousand per cent.

For Luxembourg, it was also vital to the national interest to defend the ‘community method’: where individual countries cannot veto the will of the majority and the Commission and European Parliament have a full role in decisions. Furthermore, the V4 were blocking a community measure not only on the grounds of sovereignty but also identity: they simply had no wish to admit large numbers of mainly male Muslims from the Middle East to their countries. To the Luxembourgers, this was ethno-nationalist and therefore anti-European. Although Luxembourg has practically no Muslim population to speak of, Jean Asselborn, its long-serving foreign minister, was determined to confront and make an example of the V4. Meanwhile the Hungarians and Poles especially did themselves no favours with ugly rhetoric about the migrants’ health, culture and religion, as well as provocative vetoing of EU foreign policy measures. Orbán in particular loved to sound off on the apparent threat the Muslim migrants posed to Europe’s Judeo-Christian culture to which Tusk retorted: “For a Christian it shouldn’t matter what race, religion and nationality the person in need represents.” 32

By virtue of its self-perception as the epitome of the ‘good’ EU; and since Luxembourg was not attractive to the migrants, the country said and did pretty much what it wanted without fear of reproach or pull factors. Hence Luxembourg did the opposite of hiding. It stood out, set the agenda, got confrontational, took leading positions and backed them up by meaningful gestures wherever possible. The reason it could do so with such swagger was that it felt huge ownership of a shelter it had helped to build decades previously: the European Union itself. Schengen, after all, is the name of a small town on the river Moselle. Moreover, Jean-Claude Juncker – an irascible, ill-disciplined and sentimental man of “almost Franciscan” political principles – was Luxembourg’s pro-integrationist prime minister for nearly 20 years before the crisis 33 . This is crucial to understanding the locus of the EU’s early response, where the Commission’s main proposal was a humanitarian one that also served integrationist ambitions.

Conclusion

The irregular arrival by sea of two million irregular migrants from the Middle East, Africa and South Asia to Europe was not its 9/11. No less a loss of innocence, a better parallel is Hurricane Katrina. The 2005 natural disaster ravaged the US Gulf Coast and led to a frightening breakdown in law and order in New Orleans and areas of the south east. Americans and the outside world alike struggled to understand how a nuclear superpower seemed incapable of managing a humanitarian crisis within its own borders. For everyday Europeans, the shock events of 2015 and 2016 in particular were similarly disorientating. Their expectations were that the Union would not only swiftly control the flows but perhaps intervene to stop the war in Syria itself, so the refugees could go home. Now they were waking up to Europe’s powerlessness to influence the increasingly unstable world around it. They looked at the EU and, like the US public in 2005, were baffled by its apparent impotence, not apprehending the ideological struggles within; the legal distinction between refugees and impoverished economic migrants; or the treacle feet of international cooperation in the absence of political unity. The fact that EU-flagged missions had saved well over half a million peoples’ lives at sea during the emergency – a feat unprecedented in world history – seemed to register to the Union’s credit not at all.