The Scale of Trust: Local, Regional, National and European Politics in Perspective

Jean-Sébastien F. Arrighi,

Editor, BLUEJean-Toussaint Battestini,

Lucie Coatleven,

François Hublet,

Editor-in-chief, BLUEVictor Queudet,

Editor, BLUESofia Marini

Editor, BLUE

13/07/2022

The Scale of Trust: Local, Regional, National and European Politics in Perspective

Jean-Sébastien F. Arrighi,

Jean-Toussaint Battestini,

Lucie Coatleven,

François Hublet,

Victor Queudet,

Sofia Marini

13/07/2022

Voir tous les articles

Voir tous les articles

The Scale of Trust: Local, Regional, National and European Politics in Perspective

Executive summary

It is a well-established reality that, throughout Europe, local and regional institutions are more trusted than national governments. Equally well-established is the fact that, in Southern and Eastern Europe, the European Union is more trusted than national governments. In a time of incertainty about the future of democracy and the Rule of Law on the European continent, the present working paper aims at documenting the extent and determinants of this “trust gap,” which has far-reaching implications for the legitimacy of public action.

Based on case studies of four member-states with widely different institutional structures — Germany, France, Italy and Poland — and a statistical analysis of Eurobarometer data, several important results stand out.

Despite the higher level of trust generally placed in local institutions, the member-state level of government remains politically dominant, as the initial reactions to the pandemic clearly illustrated. Hence, variations in trust in local and European institutions over time can be partly analyzed as transfers of trust from or to the national level. A negative political or economic outlook at the member-state level increases relative trust in local and European governments, which acquire new legitimacy in the process. This phenomenon is particularly clear in political contexts marked by strong government mistrust or significant territorial inequalities.

However, far from being merely a sounding board for national politics, the European and local levels of government also possess their own dynamics. Trust in local institutions appears to be closely linked to the quality of public services and day-to-day policies, and can rely on a strong emotional attachment; conversely, European institutions are more frequently trusted on the basis of abstract considerations related, e.g., to the economic and democratic framework provided by the Union’s institutions. Unsurprisingly, political representations and institutional cultures play a more important role in these processes than simple quantitative considerations about the size of the different political entities.

In view of the striking gap between citizens’ trust in the various institutional levels and the actual sets of competences with which each of these levels is endowed, this study also intends to be a call to action. In order to remedy democratic deficits in both the Union’s and member-states’ political systems, it appears urgent to provide each decision-making level with the competences for which it can rely on the broadest base of trust among the population.

Introduction: Citizens’ Trust in Local Governments is High — Trust in the EU is Ambiguous

With “NextGenerationEU,” member states are creating common debt for the first time. While some may see this as a historical step towards federalism, others are concerned about its lack of efficiency. In either case, this European-level response was created in response to exceptional circumstance. For more than two years, Covid-19 has dramatically changed regional, national, and European institutional politics. Border closures within the Schengen Zone during the first wave, the shuttering of thousands of businesses, and governments’ management of the crisis have affected citizen perception of public powers. At a time when the growing success of anti-liberal and Eurosceptic movements already highlighted a crisis of representative democracy and the Union’s democratic deficit, the “Covid-19 effect” is reshuffling the cards.

In this context, it is vital to examine European citizens’ trust in regional, national, and European institutions.Political trust is one of the pillars of a well-functioning democracy, and its level is, therefore, a major indicator of the quality of the relationship between citizens and political institutions. If trust is too low, it becomes mistrust, which can lead to social crises, crystallize societal divisions, and give rise to “anti-system” populist parties.

Available data reveals a significant correlation between the level of government and the intensity of trust: a significant difference exists in the amount of trust placed in regional and local levels of government on one hand, and the national level on the other, with local governments always being more trusted.

However, the ‘proximity bonus’ which seems to be at work in this case is not enough to explain why, in a majority of European countries, the European Union is more trusted than national institutions.

The political science literature has identified a number of other factors affecting trust in political institutions. These vary considerably across countries, levels of government, and time. Trust, as a multi-faceted process, is dependent on citizens’ perceptions of institutional proximity, emotional attachment, the political system of the country under scrutiny, its level of federalism or centralization, its overall economic and social outlook, the level of support for the federal/national government, the quality of its democracy, overall satisfaction with one’s life, etc.

This working paper will explore the relationship between trust and the scale of public action within the EU using data from the Eurobarometer and national opinion polls. It will proceed in two parts.

The first part will examine the trust gap in four member states with widely different structural, historical, and cultural features. In France, a deep and long-standing crisis of trust in the central government has materialized in the Yellow Vest movement. In Italy, the differences in trust placed in local, national, and European institutions illustrate the desire for autonomy, or even federalism, which characterizes certain regions. In the case of Germany, the trust gap reflects the tensions inherent to the country’s federal structure. Finally, in Poland, the relationships between different levels of government are marked by a strong divide between urban and rural areas, as well as prominent opposition mayors.

The second part consists of a study of the determinants of trust on the basis of statistical models (Eurostat data), which will make it possible to identify the factors affecting the trust gap between regional/local and national institutions on one hand, and between European and national institutions on another.

Together, these case studies and statistical analyses provide an overview of the relationship between the scale of public action and the level of trust placed in it, leading us to question our conceptions of the specific functions and democratic legitimacy of different levels of government in today’s Europe.

Trust gaps between the regional, national, and European levels of government: a quick overview

In order to study the interactions between the scale of public action and trust in political actors, the difference between the share of citizens who claim that they trust local and regional institutions on one hand, and national institutions on the other, is an interesting indicator. This difference is represented, for each EU member state and for a period of seven year (2013-2020), on the map shown in Figure 1.

The analysis shows that for all member states, local and regional institutions are still more trusted than national ones. The average trust gap between local/regional and national institutions within the Union is 15 percentage points. This difference is greatest in the Czech Republic, Lithuania, Slovenia, and France. It is in France that the trust gap between local/regional and national institutions is largest at 31.89 percentage points. In contrast, it is Sweden 1 , Italy, Croatia, and Ireland which show the smallest difference, ranging from 4.57 to 5.57 percentage points. But even in these countries, we can see a significant trust gap between local/regional and national institutions.

How can this regularity be explained? According to Bruno Cautrès, a CNRS (Centre national des recherches scientifiques) researcher at CEVIPOF (Centre de recherches politiques de Sciences Po/Political Research Center at Sciences Po, Paris), citizen trust in an institution rests on two pillars: the perceived proximity of the citizen to the institution and the protective role that institution plays. And so, when asking the question about a municipality or region, trust is “all the greater as the probability of observing the concrete results of public action is greater” (Arrighi et al. 2021). For Bruno Cautrès, trust given to an institution is comparable to an investment; if the institution seeks continued trust from citizens, the institution has to show citizens that their investment is “profitable.” In order for this to happen, the municipality, region, or even State, must prove that by carrying out its public functions and show that it is meeting the missions of proximity and protection with which it has been entrusted. The citizen will be more inclined to trust local or regional institutions than national institutions because it is easier to see the “return on investment” of trust for the missions of protection and proximity at the level of municipalities or regions than at the national level.

Consequently, one could expect to see member states being more trusted than the European institutions.

However, when we consider the trust gap between national and European institutions, different patterns emerge. In Figure 2, two Europes materialize: in the South, the Baltic countries, and Ireland, European institutions are more trusted than national institutions; in Austria, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Scandinavia, it is national institutions that are more trusted than EU institutions.

It is interesting to observe that in countries often described as “Eurosceptic,” such as France, Italy, and the Czech Republic (Cautrès et al. 2020), the respondents still place more trust in European institutions than in national governments. This gap is not insignificant: in France, the gap in percentage points between trust in the EU institutions and trust in national institutions is 8.32, in Italy it is 12.21, in Hungary it is 9.04, and in the Czech Republic it is 11.25. The greatest differences between trust in EU institutions and trust in national institutions are found in the Eastern European countries. Respondents in Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, and Lithuania have an average of 26 percentage points more trust in EU institutions than in those of their own country.

In Northern European countries, the gap in favor of national institutions is equally pronounced: on average, respondents from these countries placed 8.72 percentage points more trust in national institutions than in European ones. The gap is greatest in Sweden, where it reaches 14.43 percentage points, and lowest in Denmark, where the difference is only 3.43 percentage points.

Far from showing that citizens in Northern countries have less trust in European Union institutions (this trust being, in many cases, higher than that observed in the South), these figures above all attest to the high perceived efficiency of these countries’ national institutions. The fact that those surveyed in Sweden, Finland, and Germany place more trust in their national institutions than in European institutions does not in itself indicate a rejection of European integration, but rather brings us back to the proximity relationship that we have already mentioned when discussing local and regional levels.

Similarly, we should not to rush to the conclusion that the differences in trust for European institutions in Southern countries are a sign of enthusiasm for continental integration. Other reasons may in fact explain this gap. For example, perceived corruption, the degree of political and democratic crisis, and the negative reaction of citizens to illiberal pressures have a negative effect on trust in national institutions. For a country with a certain level of trust in the European institutions, a high level of corruption or citizens’ mistrust of national institutions systematically increases the trust gap in favor of European institutions, even if this does not mean that the European institutions are trusted by a majority of those polled. However, mistrust of national institutions (e.g., due to corruption) can also, under some circumstances, effectively increase the level of trust in European institutions: European institutions, despite the fact that they are distant from the country, may be perceived as more reliable, more stable, and more impartial, and therefore more capable of managing a number of political issues.

France: Centralized Government and Long-Standing Mistrust

Historically, France has been a typical example of a centralized State: the law is applied equally throughout the country, local authorities have little autonomy, and the territory is organized around districts where state representatives, prefects, and subprefects enforce the law and provide administrative oversight. Although the “great decentralization reform” of 1982 and its second phase in 2003 resulted in abolishing the prefects’ supervisory authority over local governments and strengthening the powers of the departmental and regional councils, France’s decentralized organization still stands in contrast to that of its German and Italian neighbors.

Since its launch in 2009, the CEVIPOF Political Trust Barometer has shown higher levels of trust in local, departmental, and regional institutions than in national ones. Between 2009 and 2019, only town councils received more than 50% approval, while the presidency did not receive more than 40% approval from citizens, even falling below 25% in December 2018. Political trust, compared to personal and interpersonal trust, is generally low; mistrust and fatigue with regard to public affairs were the prevailing sentiments. This “dark decade” was marked by several crises that both revealed and preceded shifts in trust levels (Cheufra & Chanvril 2019).

Through its actions and demands, the Yellow Vest movement which emerged in 2018 manifested the crisis of trust that had been apparent since 2017. The movement was characterized by the rejection of all forms of political representation, and more specifically of national institutions. Later, the Covid-19 pandemic and its subsequent handling have led to an apparent renewal of trust, which cannot, however, conceal a deep-rooted, collective pessimism in French society.

“Politicians, you will be held accountable!”: The Yellow Vests, a crisis of the central government? 2

In the tradition of the Bonnets rouges and Nuit Debout, the Yellow Vest movement rejected the traditional constraints of union demands and adopted original strategies of collective action. Through the occupation of traffic circles and areas that lack investment and have been long overlooked, as well as the temporary nature of the protests — marked by both periods of calm and intense activity — the traditional channels for protest have been turned upside down. Formed on Facebook following an increase in the domestic tax on consumption of energy products (TICPE), the first Yellow Vest protests were spontaneous and sporadic. Party affiliation is not the movement’s driving force, and it is largely made up of first-time activists; there are almost as many non-voters (21.5%), as it there are supporters of Marine LePen (18.5%), or supporters of Jean-Luc Mélenchon (22.5%).

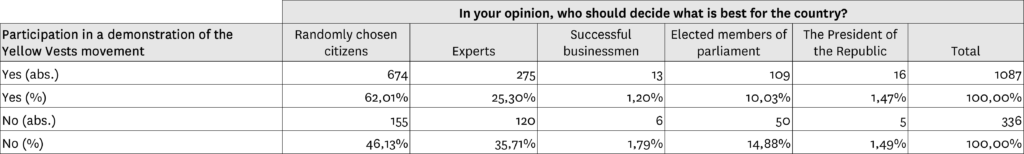

The movement is largely the result of a loss of trust in all forms of political representation. Among those who have participated in at least one Yellow Vest blockade, 62% are in favor of citizens being chosen at random to decide what is best for France, while only 10% are in favor of elected representatives. This rejection of representative democracy is not unique to the Yellow Vests; it reflects a crisis of representation that is deeply rooted in society. Indeed, 46% of non-protesters share the same opinion as the activists regarding random selection of citizens. According to the 2018 CEVIPOF Barometer (OpinionWay 2019), only 41% of French people, compared to 48% in 2017, cite voting as the best way to influence decisions made in France. In contrast, 42% of respondents cite protesting as the first- or second-best way to influence decisions made in France, up 16 points from a year before. Furthermore, 72% of respondents believe that the Yellow Vest movement represents the concerns of many French people.

A year before the Yellow Vest movement erupted, this crisis of representation was already noticeable. At that time, political trust was in steep decline: 53% of respondents trusted their local officials compared to 64% in December 2016; 29% trusted the Senate and the National Assembly compared to 44% and 43% respectively a year earlier. As a result, by December 2017, the decline in trust could be seen at both the local and national levels, although its overall level is much higher for local institutions.

In December 2018, one month after the first Yellow Vest protests, trust in municipal, departmental, and regional officials remained stable compared to December 2017 levels (54%, 43%, and 41% respectively, see OpinionWay 2018) even as it further declined for national institutions. The Senate, the National Assembly, the presidency, and the government lost 3%, 6%, 10%, and 8% of trust respectively (26%, 23%, 22%, 22% of trust respectively).

And so, if the rise of the Yellow Vest movement at the end of 2018 does indeed reflect “the breakdown of political organizations” (OpinionWay 2018), it constitutes, a fortiori, a crisis of the central government and more particularly of the presidency, which lost 10% in the space of one year. This can be seen in the protest’s dialectics, between suburban areas and large cities — especially Paris — on Saturdays, the rejection of political misrepresentation, even from François Ruffin, “the biggest yellow vest” (Marlière 2018) of any politician, and the discrediting that sooner or later affects any leading figures emerging from the movement, such as Jacline Mouraud (Lefebvre 2019). The president is also subject to the most vehement protests. The destruction of the restaurant Fouquet’s — which was the iconic gathering place during Nicolas Sarkozy’s presidential term —, the slogans and hostile plays on words regarding the Great Debate launched by Emmanuel Macron (“The Great Debate is in the street”, “We don’t want your debate, we want your departure”, Saint-Armand 2021), as well as the recurring attacks on career politicians all characterize this anti-presidential crisis.

If the Yellow Vest movement is the manifestation of a loss of political trust at all levels of representation, a crisis which has been gradually taking root in French society, its actions and demands are above all defined by a profound rejection of the presidential institution and the career politicians who uphold it.

Political Trust in the Pandemic

The three rounds of polling conducted for CEVIPOF in February 2020 (OpinionWay 2020a), before the beginning of the pandemic, then in April 2020 (OpinionWay 2020b), during the first lockdown, and finally in February 2021 (OpinionWay 2021), reveal new trends. While renewed trust in political institutions at all levels could be felt before the health crisis broke out, it seems that this crisis has reinforced this — once again, at all levels. Municipal, departmental, and regional councils, assemblies, the executive branch, the European Union, and even the Constitutional Council and the Economic, Social and Environmental Council (CESE) all saw their trust ratings increase by about 5 percentage points between February 2020 and February 2021. The feelings of fear and mistrust have also given way to general fatigue combined with a deep-seated gloom as there is still no end in sight for the health crisis.

Political trust therefore seems to have generally returned to 2016 levels following a low point during the Yellow Vest crisis. While the health crisis may have initially triggered reactions of fear and mistrust, it also gave institutions a new role and a new image that served as a reminder of their legitimacy and responsibility.

While an analysis of data can therefore illustrate the resilience of political institutions in times of crisis, a study in terms of government levels is also necessary. In fact, despite the political crises of the past five years, the trust gaps for various French institutions have remained almost unchanged. It comes as no surprise that proximity is a determining factor in the perception of politics: town councils are by far the most trusted institution among French respondents (64% trust), ahead of departmental and regional councils, which are neck and neck (56%). Respondents have the most trust in regional authorities and their local elected officials. Relatively new to the political scene, the Constitutional Council and the EESC, two oversight bodies that lie outside of the traditional political arena, enjoy considerable and growing trust ratings (47% and 44% respectively in February 2021). Parliamentary assemblies, whose popularity has remained very similar over the past ten years, come next at slightly under 40%. Finally, the President of the Republic is just ahead of the government, with 37% and 35% trust respectively in February 2021. Even though a general trend of increased trust is taking shape, the French continue to largely favor their local elected officials over national institutions, with the legislative branch having only a slight edge over the executive branch.

As Bruno Cautrès, a researcher at the CNRS and CEVIPOF, explained in a report published by the Institut Montaigne (Marin 2020), this renewed trust should not be taken as a sign that French democracy has recovered. Although public institutions still enjoy a certain degree of trust — in particular hospitals, the army, and schools (81%, 77%, and 73% respectively in the February 2021 CEVIPOF survey), and to a lesser extent the police (69%, but seen as suffering from a serious lack of resources and training) — the deep-seated mistrust of political institutions, and even more so of politicians, indicates a major crisis of representation. The survey conducted by HarrisInteractive and Eurosagency for LCI in February 2021 (Lévy 2021) regarding French political trust illustrated the general dissatisfaction with national political figures: none of them received a clear majority of positive opinions, and these opinions were very often split along partisan lines. It is worth noting that the only two figures with broad support — Édouard Philippe and Nicolas Hulot — have both recently distanced themselves from national politics against a backdrop of political tension. The CEVIPOF survey also illustrates the loss of trust in different forms of public engagement and expression: political parties and trade unions hold around 5% of trust in influencing public action, while protests, boycotts, and strikes only reach 25%, 21%, and 21% respectively. Trust in voting remains slightly above 50%.

More than a simple mistrust of a political elite deemed too distant — geographically, socially, culturally — the markedly low levels of trust in national political institutions seem to reflect a broader questioning of the state of French democracy. The erosion of trust in national institutions, which are the main decision-making entities in a country as centralized as France, may reflect citizens’ dissatisfaction with an institutional framework that no longer meets their political expectations. At the same time, doubts about the relevance, capability, and legitimacy of the political system which have been brewing for several years and which have become visible following recent crises, could strengthen both the local level and less politicized bodies such as the EESC or the Constitutional Council.

This ingrained mistrust of traditional national institutions could also benefit the European Union. In fact, even though it is still perceived as very bureaucratic, the EU enjoys a growing level of trust, at 42% — well above the French executive and legislative branches. Polls conducted by the Eurobarometer three times in 2020 regarding trust in the EU (Eurobarometer 2020abc), show the level of trust for Brussels: 53% of French respondents, for example, were in favor of the EU being better equipped to fight the pandemic, though these polls were carried out before the mishaps related to ordering vaccines. It is interesting to note that among the political models proposed by the CEVIPOF survey in 2021, the second most popular system among the French was the system of experts, with 47% in favor, which is an idea that can easily be associated with the EU.

Conclusion

The pandemic does not seem to have drastically altered the crisis of trust and representation that France has been experiencing for several years. While the Yellow Vest movement brought certain social and political divisions to light, the renewed trust in political institutions, which had begun before the health crisis, has continued over the past year, and has resulted in a return to levels comparable to 2016. Local political institutions have maintained the highest levels of trust in contrast to national institutions — both legislative and executive — which suffer from ingrained mistrust. The EESC, the Constitutional Council, and the European Union all seem to benefit from these dynamics.

The question of French democracy’s health or dysfunction is therefore reflected in this analysis. The concerns that divide French society can be seen in the twin shifts of support for democracy (84% in favor of a democratic regime, according to the CEVIPOF survey of February 2021, up 10 percentage points in one year) and for authoritarian regimes (34% in favor of a strongman, stable over the year, and 20% in favor of a military coup, up 5 points).

Historically, France has been a typical example of a centralized State: the law is applied equally throughout the country, local authorities have little autonomy, and the territory is organized around districts where state representatives, prefects, and subprefects enforce the law and provide administrative oversight. Although the “great decentralization reform” of 1982 and its second phase in 2003 resulted in abolishing the prefects’ supervisory authority over local governments and strengthening the powers of the departmental and regional councils, France’s decentralized organization still stands in contrast to that of its German and Italian neighbors.

Since its launch in 2009, the CEVIPOF Political Trust Barometer has shown higher levels of trust in local, departmental, and regional institutions than in national ones. Between 2009 and 2019, only town councils received more than 50% approval, while the presidency did not receive more than 40% approval from citizens, even falling below 25% in December 2018. Political trust, compared to personal and interpersonal trust, is generally low; mistrust and fatigue with regard to public affairs were the prevailing sentiments. This “dark decade” was marked by several crises that both revealed and preceded shifts in trust levels (Cheufra & Chanvril 2019).

Through its actions and demands, the Yellow Vest movement which emerged in 2018 manifested the crisis of trust that had been apparent since 2017. The movement was characterized by the rejection of all forms of political representation, and more specifically of national institutions. Later, the Covid-19 pandemic and its subsequent handling have led to an apparent renewal of trust, which cannot, however, conceal a deep-rooted, collective pessimism in French society.

Italy: Demands for Autonomy and Cultural Unity

Understanding the origins of Italian regionalism

Although the union of the seven states of the Italian peninsula 3 into a unified Italian state is recent, the regions of Italy have long enjoyed their sovereignty in quite the same way as the 38 German states that made up the Germanic Confederation prior to German unification. The Italian republics and kingdoms had all, at some point, experienced a golden age of economic, political and symbolic power.

It is therefore not surprising that numerous calls for autonomy, or even independence, emerged in the wake of Italian unification. The demand for autonomy became a political reality with the formation of autonomist movements at the end of the First World War. In Sardinia, the Partidu Sardu (PSd’Az), founded in 1921, is currently the oldest active Sardinian nationalist party. Sicilianism 4 has its origins in the desire for a special status for Sicily within a united but federal Italy since 1860. Finally, among the French-speaking minorities of the Aosta Valley, the German-speaking minorities of South Tyrol / Alto Adige, and the Slovenian-speaking minorities of Friuli, the desire for autonomy or even secession was formulated in reaction to the attempts at forced Italianization before and during the Mussolini regime.

It was not until the end of the Second World War that certain communities in Italy (Sardinians, Sicilians, Valdôtains, Slovenian and German-speaking minorities) were granted a certain form of autonomy. The main idea behind this concession was to mark a break with the hyper-centralization established under the fascist regime, while at the same time cutting short secessionist temptations. Thus, following the approval of the corresponding constitutional laws on 26 February 1948, the Italian regions with special status were created (Figure 4).

The process of devolution resumed when the Italian Constitution was amended in 2001, introducing new elements that moved the Italian Republic towards greater decentralization, including the principle of “equality between the State, regions and local authorities as constituent elements of the Republic” (Art. 114). However, it cannot be said that the constitutional revision of 2001 made Italy a federal republic, even if “it prepares [Italy for it, without yet achieving it” (Fougerouse, 2003). The devolution process came to a halt when the 2005 constitutional reform bill was rejected in a referendum in June 2006 by 61.29 per cent of voters. However, this halt did not mean the end of the desire for decentralization, as we shall now show.

Analysis of Italian public opinion since 2007: trust in various levels of governement and proximity

On the basis of various surveys conducted by the institute for political and social research Demos & Pi, we analyze the evolution and state of Italian public opinion on the issue of regional autonomy or independence. Let us first observe the degrees of confidence that Italians have in each of the administrative levels.

From 2007 to 2009, we observe that, with the exception of the European Union, which was the level of government in which Italians had the greatest confidence, confidence is clearly positively correlated with the proximity of the institutions to the citizen. Compared to the region or the state, it is the municipalities that enjoy the highest level of trust, followed by the region and then the state.

With the exception of the European Union, whose trust levels dropped sharply following the subprime crisis in 2008 and the debt crisis in 2011, we do not observe any major change in the ranking of these 4 institutions over the rest of our time series. It is interesting to note, however, that despite a drop in trust, the Union remains more trusted than the regional councils or the State. The increase in trust in all institutions in 2020 is explained by a “rally-around-the-flag” effect in reaction to the health crisis. In public opinion, the state seems to benefit the most from the crisis, compared to the regions, municipalities and the European Union: it is the level that enjoys the greatest increase in confidence (+10 percentage points). Otherwise, Italians have more confidence in institutions when they are geographically close to citizens. The municipality is the institution most trusted by Italians. The effect of proximity can be observed by looking at the gap between the confidence in the municipality and that in the regions or the state, which remains large over the entire period studied.

While the ranking of the various levels does not change over time, some dynamics can be observed in the light of this graph. From 2007 to 2015, the trust gap between the regions and the Italian state is rather limited, oscillating between 1 and 7 percentage points at its maximum. Starting in 2015, we notice that this gap widens; the difference reaches 10 percentage points in 2017. Between 2016 and 2019, we observe a significant gap in trust levels between the state and the regions.

Autonomy and the road to independence

The same years saw important non-binding referenda being held in Veneto and Lombardy on the very issue of autonomy and independence. On October 22, 2017, voters in Lombardy and Veneto were called to vote to give their region a mandate to negotiate more devolution of competences from the central state. In both regions, an overwhelming majority supported this initiative: in Veneto, 98.1% of voters were in favor of more autonomy for the region with a turnout of 57.2%. In Lombardy, the result was mixed: while 96.02% of voters were in favor of more devolution, the quorum was not reached with only 38.21% of voters who came out to vote on the issue. This was not Veneto’s first attempt at addressing this question, as in 2014 the region had already held a non-binding referendum with the question “Do you want Veneto to be a federal, independent and sovereign state?” where 89.1% of voters voted in favor of independence before it was ruled illegal by the Italian Constitutional Court. The vote instead paved the way for more autonomy without, however, talking about a special status for the region.

This “independentist” momentum prompted the Demos & Pi institute to conduct a poll in several Italian regions in 2014 to measure their desire for independence (Demos and Pi, 2014). Only regions with a statistically significant number of responses were included in the study. The survey question explicitly asked respondents whether or not they favored their region’s independence from the rest of Italy. We find that the regions with the strongest desire for independence are the island regions that already enjoy a special status by virtue of the Italian Constitution of 1947, as well as Veneto. At 44%, Sicily expressed a minority but strong support for independence, as did Sardinia (45%); as for Veneto, 53% of respondents called for the independence of their region. Finally, the other regions where support for independence amounts to about a third of respondents are Piedmont, Lombardy and Lazio. This data thus echoes our earlier claim that Italian regions that possess their own economic, political and symbolic history are more likely to be in favor of some degree of autonomy, or even a return to their own sovereignty. It is unfortunate that this survey does not include data on support for independence in South Tyrol, Valle d’Aosta and Friuli, regions where support for independence would have been worth analyzing.

Yet, these estimates of support for independence in various regions contradicts other poll estimates obtained in the months preceding the autonomy referenda in Lombardy and Veneto (Demos & Pi, 2017). The latter poll estimates the demand for autonomy in Veneto, Lombardy, and Italy as a whole. When distinguishing between the demand for autonomy and the demand for independence, support for more autonomy is 52% in Lombardy and 57% in Veneto while support for autonomy is only 9% in Lombardy and 15% in Veneto. Have demands for autonomy and independence eventually fused at the ballot box? Would the majority of citizens in these regions be in favour of greater autonomy for their region, without wanting to cut ties with the Italian Republic? Similarly, Demos & Pi (2014) shows that while 55 per cent of respondents answered yes to the question “are you in favour of or against the independence of Veneto?,” only 28 per cent supported “achieving full independence for Veneto” compared to 30 per cent who said “electing competent parliamentarians,” 20 per cent who said “more autonomy, real federalism” and 17 per cent who said “parliamentarians capable of defending the interests of the regions.” The demand for independence, sometimes measured at very high levels in these regions, would then only be the expression of dissatisfaction with a central state perceived as failing to respond to the regions’ demand for autonomy. The support for independence observed in the polls can therefore be interpreted as a sign of a one-time radicalization of the respondents on the issue of the demand for autonomy.

Regarding the demand for autonomy proper, Demos & Pi (2019) shows that, on a scale of 1 to 10, 63% of respondents rate the question of “granting of greater autonomy to regions that demand it” as important (above 6), versus 32% who rate it below 5. This is the maximum level reached compared to March and May 2019, when 59% of respondents gave a score above 6 for the same question. The importance given to this question is lowest in the island and southern regions with only 57% of respondents giving importance to this question. While we can assume that the non-insular southern regions must be pulling down this score, greater autonomy still appears to be supported by a majority of respondents from southern Italy. Unsurprisingly, support for autonomy is strongest in the northwest and northeast, where the Lega Nord is very active: in the regions of Veneto, Trentino and Friuli, the importance of the issue reaches 86%, while in the regions of Valle d’Aosta, Piedmont, Lombardy and Liguria the importance of the issue of autonomy is evaluated at 63%. Next come the regions of central north and central south, where the importance of the issue of autonomy is evaluated at 60%.

Let us now analyze the demand for autonomy by partisan preference. According to the same survey, support for greater autonomy is strongest among Lega supporters: 82% of Lega supporters give particular importance to the demand for regional autonomy. Next come supporters of Forza Italia, for whom the issue is considered important by 72% of respondents, and finally supporters of the Movimento Cinque Stelle, with 71% of supporters of the movement who attach importance to this issue. Support for the demand for autonomy is lowest among supporters of the Partito Democratico (PD), with only 43% of PD sympathizers giving importance to the issue of regional autonomy.

In sum, a non-negligible part of the Italian population clearly supports an extension of the scope of their region’s competences. This demand for more autonomy is sometimes conflated with the demand for independence, even though the latter appears marginal in polls whenever a clear distinction is drawn between the desire for autonomy and the desire for independence.

“Italiano, malgrado tutto”

Other studies tend to show that cultural unity takes precedence over secessionist views. This suggests that despite widespread desire for autonomy, the demand for independence could be merely a form of radicalization of the demand for autonomy, and that once the varnish of protesting independence is scraped off, “siamo italiani, malgrado tutto” (“in spite of everything, we are Italians”).

Demos & Pi (2019) showed that only 29% of Italians felt that they belong mainly to their region (as their first or second choice), which places this level of government only in 4th position in the ranking. In the top three, we have “the Italian nation” for 42% of respondents, their municipality for 33%, and “the world” for 31% of them. Only 15% of respondents answered that they belong to the “North” and 14% to the “South,” placing these two options at the very bottom of the ranking. More interestingly, when we look at the answers by political preferences, we see that for Lega voters, belonging to Italy is the most important by a very narrow margin, with 31% of Lega supporters answering that they feel Italian, compared to 30% who answer that they belong to their region or commune. Among the supporters of the Movimento Cinque Stelle, the feeling of belonging to the region or the city takes precedence with 29% of the answers, while belonging to Italy comes in third place with 22% of the answers, just behind the feeling of belonging “to the South” which gets 25% of the answers.

The feeling of belonging to Italy is shared by a majority of the population, as is the attachment to Italian unity, which 89.1% of Italians rate very positively or positively (Demos & Pi, 2011). Only 7.5% of respondents have a negative perception of unity. The regions with the lowest support for unity are the islands and the South, where support is 90%, and the Northwest and Northeast, where support ranges from 83% to 84%. Support for unity is therefore overwhelmingly strong even in regions displaying separatist tendencies. In the same vein, when looking at party preferences, only Lega supporters are only 70% positive about the advent of Italian unity, while support reaches or exceeds 90% in all other political formations. The figure of unity, Giuseppe Garibaldi, is perceived very positively among Italians: 91% of them think that the “father of Italian unity“ has left a positive mark on the history of the country, placing him at the top of the ranking of historical figures who have contributed most to the influence of Italy in the world.

According to the same survey, in 2011, 51% of Italians thought that Italy would be “more federal” by 2021 and 38% thought that Italy would be a federal republic, but 66% thought that it would be less united. This shows that the desire for more autonomy takes precedence over the desire for independence. Italians are very attached to their unity, even if they are sometimes critical of the form it takes.

Conclusion

From the opinion polls we have analyzed, we can observe that despite the strong demand for autonomy, and sometimes independence, expressed by Italian citizens, the country’s public opinion shares a strong desire for cultural unity. The demand for autonomy, which sometimes expresses itself in calls for total independence from the rest of the Italian Republic, can be linked to the division of Italy into several political entities over several centuries. Strong regional identities have thus emerged, without supplanting the sense of national belonging.

Italy as a nation-state is the result of the unification of small powers with their own history. Unity, which is strongly desired and widely celebrated, does not supprress Italians’ regional and communal attachments. Local levels of government are, in fact, more trusted than the central state. The demand for regional autonomy expressed by a part of Italian public opinion is not intended to challenge the unity of the country, but rather to create tools that allow unity to be preserved while respecting the diversity of the peninsula. It is not separatism that is expressed in these opinion polls, but rather a desire to transform the form of the Italian state from an unfinished decentralized state to a federal state.

Germany: Regional Freedom, Federal Distrust?

Germany is not only constitutionally a Federal Republic, but also one of the countries with the strongest regional powers worldwide. The Regional Authority Index (Shair-Rosenfield 2020; Hooghe et al. 2016) of the German Länder, which quantifies the extent of the powers granted to regional levels of government, was 27 in 2018, compared to 26 for Swiss cantons, 24.6 for U.S. states, and just 18 for Italian regions. The Länder are home to strong regional cultures and identities, which give rise to largely idiosyncratic political dynamics. In Bavaria, for instance, a truly regional party, the Christian Social Union (CSU), which does not run for office in any other state, dominates regional political life. After the “turning point” (Wende) of 1990, a new West-East cleavage emerged (Jun et al. 2008). The six “new Länder” that joined the federal Republic in 1990 have since been characterized by specific political trends, the most symbolic of which is the overrepresentation of right-wing nationalist (AfD, NPD) and radical left-wing parties (PDS, later Linke) at the expense of the traditional center-left and center-right groups.

German politics is also characterized by a relatively complex culture of coalitions, within a party system that currently features six main parties and in which the two former “mass parties” (Social Democrats and Christian Democrats) are permanently weakened (Nachtwey 2018). Each of the sixteen regional governments, as well as the federal government, is formed on the basis of such coalitions. As the Länder are granted extensive powers, this system means that the different regions can diverge quite widely in the policies they pursue. Some of these regions are the equivalent of a medium-sized European nation; the most populous region, North Rhine-Westphalia, has a population of almost 18 million, while the second and third largest, Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, have populations of 13 million and 11 million respectively.

Analyzing the trust gap

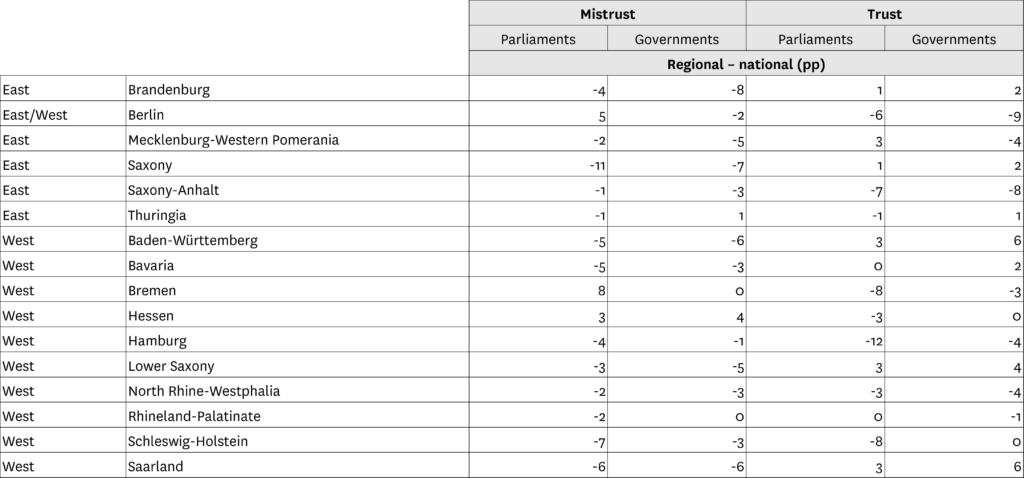

A number of studies have measured citizens’ trust in the different levels of political decision-making at the level of individual German Länder. In a major survey commissioned by the Bertelsmann-Stiftung in 2017 (Unzicker et al. 2019), respondents from each of the Länder were asked about their trust in the regional parliament (Landtag), the federal parliament (Bundestag), and the federal and regional governments. The answers to these questions allow us to assess the trust gap between the two main decision-making levels.

For both governments and parliaments, we can examine the difference between the proportion of respondents reporting “high or very high trust” in the regional level and the proportion giving the same answer about the national level. Similarly, we can observe the difference between the proportion of people indicating “low or very low trust” in the state level versus the federal level. It should be noted that a bias may have been introduced into the questionnaire in favor of the “neutral” response, which was chosen by a majority of respondents, because respondents had to declare a “high” level of trust in the parliament or the executive in order for their answer to be classified as “positive.”

With regard to trust (answers of “high” or “very high” trust), no clear pattern emerges. In eight of the sixteen Länder, trust in regional institutions exceeds trust in national institutions, while in the other eight the opposite is true. The result is quite different regarding mistrust (answers “low” or “very low” trust), since in 13 out of 16 regions mistrust of the federal government and parliament exceeds that of the regional institutions. For both indicators, in a majority of cases (26 out of 32), the gap is the same for parliaments as well as for governments.

The strong institutional weight of the Länder in Germany is therefore not associated with increased trust in regional democracy. The proportion of the German population who say they have “high” or “very high” trust in both levels of government is exactly the same at 29%. At the same time, less mistrust is expressed towards regional governments than towards the federal government in more than three quarters of the regions, with an average difference of three percentage points. This difference is more pronounced in the East than in the West and seems to be increasing in regions with a strong regional political culture (Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg, Saarland, Saxony, Schleswig-Holstein). This substantial difference in the “negative” dimensions of trust only in one of the most federalized states in the world deserves a closer analysis.

Some of the reasons advanced to explain the trust gap between the two levels of government appear to be less relevant in the case of Germany. The division of responsibilities between the two levels is more egalitarian than in many other States. Moreover, the regions are very large, which makes it impossible to consider most of the Länder as purely “local” authorities. Finally, especially because of the practice of Grand Coalitions, the proportion of voters represented in the federal government is particularly high. In 2017, in six out of sixteen regions — all in the west and representing more than 60% of the country’s population — the proportion of the electorate supporting one of the two parties in the federal government (CDU or SPD) was higher than the proportion that voted for one of the parties that made up the Länder governments in the previous regional elections. This is especially due to the significant electoral weight of the CDU and SPD at the time of the study. Hence, three of the proposed mechanisms (authority, proximity, representativity) could be partially or totally ineffective, at least in the Western part of the country.

Rather, these differences could be explained through matters of identity, the relationship to the federal state and political culture — in particular the desire for autonomy —, the rejection of politics, and the general socio-economic situation. While the last point is probably the least conclusive in view of the examples mentioned above, the strong regional bounds of important fractions of the population could, together with the specific political dynamics of some of them (most notably Bavaria), explain a more frequent rejection of “Berliner” politics. In this case, the lower level of trust in the federal government, rather than being a sign of indifference to regional politics, would reflect a real attachment to the regional level of government and its autonomy. A recent study by Kühne et al. (2020) suggests that the trust gap in favor of the regions is real, and materializes not only with respect to the federal level, but also with respect to the municipal level: higher satisfaction with, or trust in, regional institutions does not necessarily imply a specific rejection of the federal level, but rather a preference for the regional level over the other levels of government.

At the same time, the sentiment of Politikverdrossenheit (political fatigue) described since the 1990s in Germany, and which is in line with a more general European pattern, may explain another fraction of this trend (Unzicker 2013). German law grants most legislative powers — i.e., true political powers— to the federal government, whereas the implementation of these laws is mostly the responsibility of the Länder. If everything that is “political” is subject to negative preconceptions, then the activity of the federal government, which receives the most intense media coverage and holds the bulk of the legislative powers, should be more directly affected. By contrast, regional policy — which is less controversial and may be perceived as less important — would be more likely to provoke reactions of indifference than rejection. In this light, it seems natural that the level of mistrust towards the federal authorities would be higher, but this would not necessarily indicate a greater interest in regional politics by citizens.

Without drawing definitive conclusions, it can be suggested that two main and somewhat antagonistic mechanisms — the strength of each region’s own political culture and the interplay between the constitutional distribution of powers and the Politikverdrossenheit — play an important role in the federal-regional difference observed in Germany, but that this difference can be observed almost exclusively in the negative aspects of the relationship to political institutions.

Did the COVID-19 pandemic reshuffle the cards?

At the beginning of 2020, on the eve of the coronavirus pandemic, the Forsa Institute’s trend barometer (RTL 2020) showed the following numbers regarding trust in political institutions: Federal President Frank-Walter Steinmeier, who mainly acts in a representative capacity, was trusted by 73% of respondents. This was followed by Chancellor Angela Merkel (50%), mayors and town councils (48%), regional governments (47%), the Bundestag (41%), the EU (40%) and the federal government (34%). The difference between national and regional governments is considerable at 13%. At the beginning of 2021 (NTV 2021), despite an increase in trust for all institutions, this order had changed: behind the Federal President (76%, +3pp) and the Chancellor (75%, +25pp), the Federal Government (63%, +29pp) now exceeded the regional governments (60%, +13pp), mayors (58%, 10pp), the Bundestag (54%, +13pp) and the EU (38%, -2pp). This trend reversal, which was already quite noticeable in the interim survey conducted in May 2020, validated the federal government’s action in the crisis while at the same time partially penalizing regional governments whose actions were often perceived as inefficient and divided. On the one hand, the federal government, which benefited from Chancellor Merkel’s high popularity, was seen as more protective despite its very limited executive powers in terms of crisis management. On the other hand, the regional governments, which were at the forefront of the political response and whose real protective capacity was therefore greater in many respects, fell short of expectations. Hence, despite a significant increase in trust, which can be explained by the need for protection mentioned above, the regional level has seen its relative popularity decline in favor of the federal level during the crisis.

At the same time, the way citizens in the different German regions perceive the quality of crisis management is very heterogeneous (Kühne et al. 2020). While the Bavarian government’s crisis management policy was rated 7.2 out of 10 on average by voters, the Brandenburg government’s score was only 5.9. As such, Bavaria’s Minister-President Markus Söder (CSU, EPP) has benefited in the polls from his proactive actions and tough talk during the Covid-19 pandemic. In March 2021, he was the second most popular politician in the country behind the chancellor (Kleine et al. 2021). In contrast, Armin Laschet (CDU, EPP), Minister-President of North Rhine-Westphalia and the CDU’s nominee for Chancellor, was increasingly unpopular, presumably due to his government’s difficulties in dealing with the region’s epidemic. This region has been the scene of several large clusters, notably in the Tönnies slaughterhouse in Gütersloh, and its administration has not allowed Armin Laschet, who takes a less restrictive approach than his Bavarian counterpart, to impose his authority in the rest of the country. However, Kühne et al. call for caution when analyzing the causes of the positive or negative evaluation of crisis management by the different regions. This is because this evaluation depends as much on the crisis management itself as on the base of popularity of the different actors regardless of the crisis.

Since the German Länder had almost exclusive authority over healthcare at the operational and administrative levels during most of the crisis (Coatleven et al. 2020), one might expect to see a strong correlation between the perceived quality of crisis management by regional governments and the trust gap between the two levels of government. This is confirmed by the data at the two extremes of the distribution (Kühne et al. 2020): the regional governments with the largest trust gap between the federal and municipal levels (Bavaria, Mecklenburg) have high crisis management scores, while those with the smallest trust gap (North Rhine-Westphalia, Berlin) have the worst crisis management scores. Between these two extremes, however, this correlation is much less clear.

The management of the Covid-19 pandemic in Germany has been accompanied in some places by criticisms of federalism as a creator of heterogeneity and an obstacle to decision-making. Even less traditional parties, such as the Bavarian CSU (Kleine et al. 2021), actively supported the centralization of certain powers. At the same time, the subsidiary approach to crisis management in Germany has allowed for greater flexibility and quicker feedback while preserving the role of the different institutional levels and checks and balances (Coatleven et al. 2020). Regional politics have played a major role in this, and many regional governments have been able to show leadership. The Chancellor, who benefited most from increased popularity, played a coordinating, political, and moral leadership role, while many powers were left to the regional governments. The crisis is thus unlikely to have caused a lasting weakening of federalism or a reversal of the trust gap between the two levels of government.

Conclusion

In one of the most decentralized federal States in the world, the trust gap between federal and regional institutions remains modest. While there is clearly less mistrust of regional institutions than of federal ones, this gap can be explained both by a specific attachment to the regional level and by a general political fatigue, which has a greater effect on the federal level. In addition, two interesting trends can be observed with regard to the pandemic: on the one hand, a reversal of the previously observed dominant position, which saw the federal authorities, identified as more protective, surpassing the regional authorities in terms of trust during the crisis; and on the other hand, a heterogeneous evolution according to the regions, in which certain states (Bavaria, Mecklenburg) distinguish themselves by a particularly high level of trust, while in others (Rhineland, Berlin), the governments are faced with a more pronounced mistrust.

Poland: Geographical Cleavages and Municipal Mobilization

Centralisation and decentralisation in Poland since the end of the Cold War

Among waves of centralisation and decentralisation following the demise of communism in Poland, the country presents today peculiar patterns in terms of governance as well as loyalties at different levels. Indeed, the experience of self-government has promoted the involvement of social groups hitherto only marginally engaged in active political participation (such as women, reports Matysiak 2015). On the other hand, the widespread practice of contesting local elections as independent candidates has partially contrasted the population’s dissatisfaction with politicians and political parties. Overall, therefore, local authorities are perceived as closer to the citizens and tend to be more trusted than the central government. Moreover, the sharp socio-economic divisions in Poland overlap the urban-rural cleavage, thus generating distinctive voting behaviours in large cities compared to the countryside. This leaves room for opposition parties, whose numbers are diluted in national elections, to mobilise support at the local level (especially around mayors) in a few nerve centres.

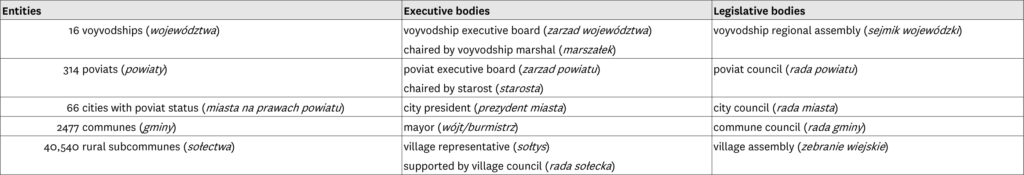

Poland’s territorial division is currently articulated over 3 main levels (Central Statistical Office report 2020). The largest territorial units are the provinces (voyvodships), administered jointly by a governor (volvode) and a locally-elected assembly (sejmic). The former is appointed by the Prime Minister, therefore acts as the local representative of the central government. The assembly, on the other hand, is entrusted with a 4-year mandate and in turn elects the executive office (zarzad województwa) and the marshall (marszałek). At present, there are in total 16 provinces. Secondly, counties (powiaty) are the intermediate level of territorial division, each with its own elected council. In total, there are 380 counties, 314 rural and 66 urban. Finally, the lowest level consists of the districts (gminy), in which voters directly elect local councillors and mayors. In total, there are 2477 districts, of which 301 are urban, 1533 are rural and 642 are urban-rural. This setting follows the Local Government Reform (November 1997-end of 2000), reducing the number of provinces, keeping the districts and re-introducing the counties (Ingham et al. 2011). Figure 9 summarises the articulation of local government organs in Poland.

In practice, municipalities are responsible for the majority of basic services, including social care and primary education (Kukołowicz & Górecki 2018). This also allows for the establishment of a clear chain of responsibility, potentially leading to sanctioning the incumbents for disliked policies. Conversely, there appears to be very little alternation at the local level. Quite the opposite: most incumbents stand again (successfully) in the following elections. Indeed, some analyses (Kukołowicz & Górecki 2018) have shown the huge advantage that incumbent candidates seem to enjoy. Since local governance includes the provision of several basic services, the administration can control the amount of resources and benefits to distribute as well as the timing thereof. This allows not only for mechanisms of “name recognition” among old candidates, but in some cases mimics clientelistic relations. Similar tendencies were also documented by Mares and Young (2018) in their analysis of Romania and Hungary. In Poland, expenditures per capita and incumbency have indeed been proved to be important drivers of the executive officials’ electoral success — an effect which is bigger for parties in the national government at the time of elections (Kukołowicz & Górecki 2018).

These tendencies may have even increased after the recent electoral reform in 2011, replacing in several municipalities the open-list proportional system with single-member districts and majoritarian first-past-the-post rule. Indeed, this has limited the number of party candidates while increasing the number of independent (unaffiliated) competitors (Gendźwiłł & Żółtak 2017). A second relevant aspect of the reform is that it helped concentrating the powers in the hands of mayors, thanks to the consolidation of supportive majorities in the municipal councils.

This empowerment trend is being partially reversed today, with a disguised recentralisation of power — especially investing local authorities representing the opposition. Although grounded more in factual practices 5 than in formal legal reforms, this has increased the national government’s oversight on local administration, in some cases even setting standards for local services (Council of Europe 2019). This not only impairs the quality of local self-government but also undermines the principle of subsidiarity, embedded in the Polish Constitution. Such phenomenon could be traced back to the rivalry between the central government, expressed by the Law and Justice (PiS) party, and some opposition branches (mainly concentrated in urban areas) whose weight is overall diluted in national contestations but which do prevail at the local level.

It was evident that PiS had obtained most of its votes from rural constituencies in both the 2015 and 2019 elections. This comes as no surprise, since this is where the party mainly concentrated its campaign. Instead of tackling the structural divergence between centre and periphery, however, it seems that the government has attempted hampering local officials and their decision-making powers. For these reasons, the opposition forces advocate an increase in decentralisation and further empowerment of the voyvodships’ provincial governments (Gagatek & Tybuchowska-Hartlińska 2020).

The urban-rural divide

The analysis of data referring to the 2015 parliamentary elections indicates that the urban-rural divide is the most influential factor predicting voting behaviour in Poland. Indeed, urbanisation appears more relevant in explaining geographical patterns of electoral results, even more than economic conditions and historical legacies (Marcinkiewicz 2018). More specifically, high urbanisation seems to be associated with higher votes for socially moderate or progressive parties and lower votes for conservative or populist parties. This is in line with the prototypical image of young, liberal city dwellers versus older, conservative inhabitants of small centres (Matraszek 2020). It is also important to highlight, however, that in the Polish context the urban-rural cleavage overlaps several economic dimensions. For instance, Ingham et al. (2011) show that rural development deficit goes hand in hand with higher unemployment rates. Figures of the OECD further show large regional disparities, particularly evident in the lower living conditions and higher poverty rates of rural households, compared to urban ones (Council of Europe 2019).

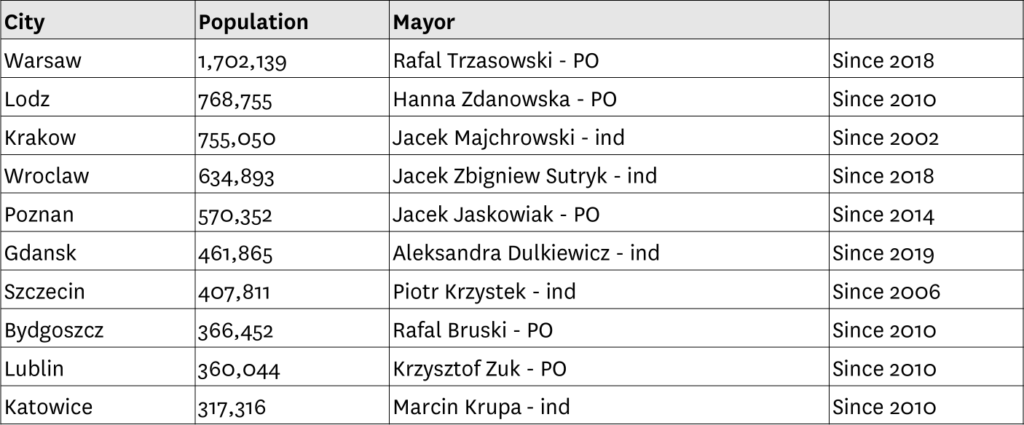

Anyhow, although these differences can lead to blurred results for national (parliamentary or even presidential) elections, the distinctive electoral patterns emerge particularly in the case of local elections. This is of course due to the territorial arrangements, but also to the degree of urbanisation: although 234 current mayors belong to the governing party Law and Justice (PiS), the 10 largest cities are all governed by independents or opposition parties (especially Civic Platform, PO). An overview thereof is provided in Figure 10. This is particularly striking since in the 2018 regional elections, held on the same day as the local ones, the PiS obtained the largest vote share, winning the majority of seats in 6 of the 16 provincial assemblies and gaining control of most local councils (Gagatek & Tybuchowska-Hartlińska 2020). There thus seems to be a discrepancy between political loyalties at different levels of government, with independent candidates being especially privileged in the local contexts.

Independent candidates

Poland has a rich and relatively long tradition of independent candidates, as shown by studies concentrating specifically on the local elections held in 2002, 2006 and 2010 (Gendźwiłł 2012).

This could, however, be due to the fact that most incumbents re-stand at the next election, therefore consolidating the power they might have gained in the early 2000s. Particularly then, in fact, several actors entered politics embracing the same anti-partisan spirit which had informed the local administration reform at the end of the 1990s (Gendźwiłł & Żółtak 2014). In general, in Poland there are incredibly low levels of party identification and membership (van Biezen et al. 2012) and trust in political parties is also very low. The party system is still not territorially rooted, and the local articulations of parties are underdeveloped. Conversely, a large share of candidate-mayors contests elections as independents, not being affiliated to any political party. All in all, they are credible and serious competitors even for the most established national parties, presenting themselves as more direct representatives of people’s needs, beyond party affiliation.

The presence of so many unaffiliated politicians at the local level is probably one symptom of the overall dissatisfaction with democracy and low trust in institutions and elected representatives (Klamut & Kantor 2017). As already evident in earlier studies, the political landscape in Poland presents a highly polarised electorate, segmented particularly along the urban-rural cleavage. The 2020 presidential elections are only the latest example thereof.

The 2020 presidential elections and the role of mayors

Initially scheduled for May 2020, the presidential elections were postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic and finally held on 28 June (first round) and 12 July (second round). This delay rejuvenated the opposition party Civic Platform (PO), which replaced its candidate Malgorzata Kidawa-Blonska (whose preference rate had dropped below 10%) to rally instead around the mayor of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski. The brutal election campaign revolved around the currently most divisive issues in the country — such as the LGBT+ community — and showed once again the attempts of the governing party to oppose the urban elites represented by Trzaskowski in favour of the poorest and oldest dwellers of rural areas, to whom is directed heavy social spending (Wanat 2020).

The 2020 presidential elections also saw the participation of Szymon Hołownia, a complete newcomer to politics but a well-known TV presenter and writer. Similar to the attempt by Paweł Kukiz in previous elections, he contested as an independent, leveraging on the widespread sentiments of disillusionment with politicians and political parties (Szczerbiak 2020). Despite, as the evolution of the polls shows, the postponement of the elections might have penalised Hołownia, at the first round of presidential elections he secured nearly 14% of the votes, behind Trzaskowski with 30.5% and Duda with 43.5%. The support gathered by such a strongly anti-establishment candidate might further signal Polish peoples’ mistrust with the whole political class (Machalica 2021).

The overall participation in the second round of the elections was nearly unprecedented, presenting the second-highest turnout since 1989 (Matraszek 2020). In the end, Duda was confirmed president with 51% of the votes, with Trzaskowski barely reaching 49%. The incumbent also managed to conquer 44 districts in which the PO candidate, Bronisław Komorowski, had prevailed in 2015. None of them, however, are cities with powiat rights. Conversely, Trzaskowski won in 7 districts formerly controlled by Duda, 5 of which are cities with powiat rights. This further shows evidence of the already mentioned urban-rural division (Matraszek 2020).

Although it is difficult to tell how much of the support for Trzaskowski actually derived from a preference for his party rather than his personal features, the huge mobilisation in his favour can be interpreted as an attempt to contrast the governing party. The fact that such opposition is embodied by a mayor is, however, illustrative not only of the deep cleavages separating the largest cities and the poorer countryside, but also of the potentialities for local authorities to voice and represent the preferences of citizens that do not support the current central government. Therefore, providing safe spaces for self-government and real autonomy at the local level is all the more crucial to safeguard the quality of democracy.

The assassination of the mayor of Gdansk in January 2019 during a charity event can also be regarded as symptomatic of the huge polarisation and tense political climate in Poland. Pawel Adamowicz had been mayor since 1998 and his mandate, renovated at the latest elections, would have ended in 2023. Although running as an independent since 2015, he was close to his former party Civic Platform – that had endorsed his candidature – and notorious for his anti-government stances. Already in 2017, his liberal positions on refugees and LGBT+ rights had made him the target of far-right groups awarding “political death certificates” to progressive politicians. Although president Duda strongly condemned the attack which was only indirectly motivated by political reasons (the attacker blamed Civic Platform for his arrest in the past), the widespread hate and political violence 6 are connected to the deep polarisation in Polish society, which is largely driven by confrontations at the elite level (Tworzecki 2019).

On the other hand, the attempt by the opposition to rally around a liberal but independent candidate closely resembles the success experienced in 2019 by Gergely Karácsony as candidate for the mayoral elections in Budapest. He then strongly promoted the coordination among the mayors of the capitals of Visegrád group countries (Hungary, Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia) which led to the signature of the so-called “Pact of Free Cities” in December 2019. This alliance reunites Karácsony and Trzaskowski with the mayor of Bratislava Matus Vallo (also elected as an independent) and the mayor of Prague Zdeněk Hřib (member of the Pirate Party) and states their commitment to the protection and promotion of the values of “freedom, human dignity, democracy, equality, rule of law, social justice, tolerance and cultural diversity” (Deutsche Welle 2019). The mayors claim to represent the most lively, diverse and economically thriving centres of their countries, which in recent times have had frictions with the EU due to allegations of corruption and deterioration of the rule of law.

Accordingly, the signatories have suggested that part of European funds — including the recovery funds allocated in the frame of the response to the Covid-19 pandemic — should be awarded directly to the cities, thus bypassing the central governments whose policies are often criticised as being at odds with some fundamental values of the European Union (Dimitrova 2021). Currently, they lament, cities are excluded from the drafting process of the national recovery plan, as reported by Eurocities (2021).

Trust figures

Indeed, Poles seem to have good confidence in local administrations and how they handle funds. In a 2018 poll from the CBOS, citizens expressed their satisfaction with local government bodies: 67% of respondents have a good/very good opinion of their mayor, with only 17% reporting the opposite opinion; 64% of respondents think that the communal council is doing a good job (16% have a negative opinion) and 49% reported that financial resources are properly managed by city or commune authorities, with only 20% disagreeing (CBOS 2018).

In 2020, examining which public institutions are deemed more trustworthy by Poles, CBOS (2020) reports overall high confidence in local authorities (indicated by 74% of respondents). Similar levels of trust are shown towards charitable institutions (some of which above 80%), armed forces and the police (83% and 71% respectively) but also international organisations (NATO 80%, the EU 73%, the UN 72%). Conversely, only 46% express confidence in the government, 33% in the Parliament and a mere 24% in political parties (distrust prevails in both the latter cases, with 45% of respondents declaring not to trust Parliament and 56% not trusting parties).

Interestingly, although appreciation of the European Union is at its highest, there are important differences based on party preference. Indeed, a 2020 poll conducted by the ECFR reported that only 13% of PiS voters tend to trust or strongly trust the European Commission, 56% distrust or strongly distrust it, while 30% are undecided. Conversely, among people who did not vote for PiS in the 2019 parliamentary elections, 37% tended to trust or strongly trusted the European Commission, with 34% undecided and 30% who tended to distrust or strongly distrusted it. (Buras & Zerka 2020). Although not unexpected, these figures show another realm in which political and partisan polarisation shapes public attitudes in Poland.

Conclusion

The electoral victories of Law and Justice (PiS) suggest a widespread support for that party and the national government. The specificities of the Polish context, however, deserve better consideration: indeed, there are sharp differences in allegiances at the national, regional and local level, especially following the urban-rural cleavage. Polish society is strongly polarised between more conservative, older inhabitants of the countryside and younger and more liberal city dwellers (divisions even reinforced by the socio-economic differences in most and least urbanised areas), which translates in distinctive voting patterns. The limited alternation allows local authorities to maintain power for long periods, thus reinforcing people’s trust through a combination of mechanisms of name recognition and clientelism. Similarly, the widespread practice of contesting as independent candidates allows them to break away from the negative reputation that politicians often have in Poland. In this context, several episodes have suggested the potential for mayors to act as counterpowers, mobilising opposition forces: examples include Rafał Trzaskowski’s presidential campaign, or Robert Biedroń’s (former mayor of Słupsk) co-leadership of the political alliance called The Left. The recent attempts by the central government to increase control on local administration therefore risk further suppressing the possibility to express dissent. On the other hand, the deep divisions between cities and countryside would need to be levelled, beginning with socio-economic development, to at least partially curb the huge polarisation threatening the Polish public sphere.

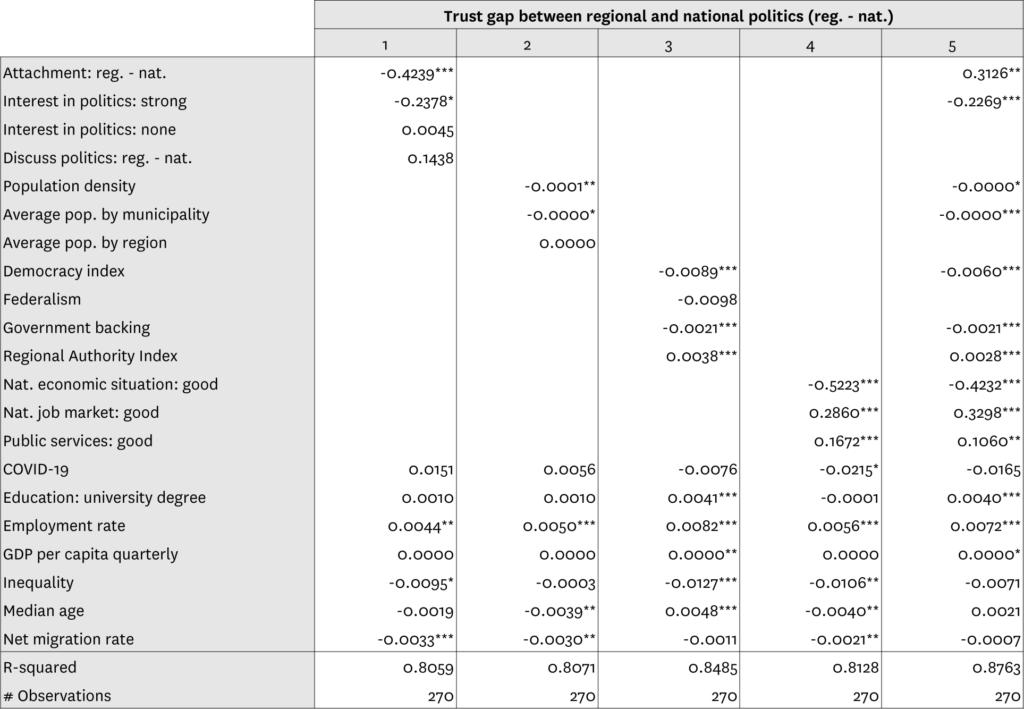

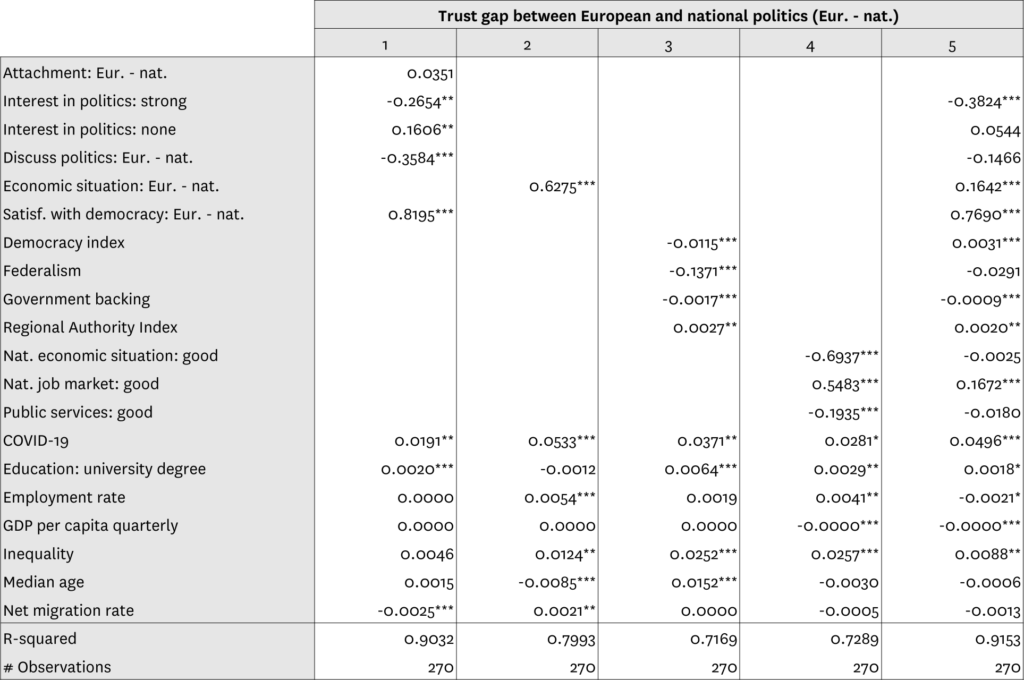

Understanding the Determinants of Trust in Political Institutions

After having examined the sharp differences in institutional trust at different levels and in different countries, we could wonder about what factors determine such variation. It is possible to retrace two main perspectives in the academic literature addressing confidence in the institutions and its determinants (Džunić et al. 2020). The first one revolves around cultural factors, linking trust to values, beliefs and cultural norms which can be shared and absorbed through socialization processes (Almond & Verba 1963, Putnam et al. 1993). In this sense, trust is considered exogenous to the political realm, rooted in micro-level factors influencing individual experiences. It is only built in the long term, and can be modified by slow generational changes. The opposite approach relies instead on an institutional perspective, considering trust as politically endogenous, depending on policy outputs and perceived institutional performance (Easton 1965, Mishler & Rose 2001, 2005). It would therefore be subject to more immediate modifications, since trust levels are influenced in the short-term by rational and pragmatic considerations.