The Future Of AI Depends On The Choices We Make

Daron Acemoğlu

Nobel Prize Laureate for Economics17/10/2024

17/10/2024

Voir tous les articles

Voir tous les articles

The Future Of AI Depends On The Choices We Make

This article is a transcription of the Inaugural Albert Hirschman Lecture “Can Technological Progress Build Shared Prosperity?”, launched by the UNESCO Management of Social Transformations (MOST) Programme on October 8th at UNESCO in Paris. It has been edited by Le Grand Continent to ensure clarity and readability in its written form. The Albert Hirschman Lectures is a new UNESCO initiative to promote dialogue on pressing global challenges, to catalyze intellectual exploration in the social sciences and inspire scholars, policymakers and civil society. Through this annual lecture, UNESCO provides a platform for high-caliber intellectuals and renowned scholars from various disciplines to discuss global issues in an interdisciplinary context.

Versions française et espagnole disponible dans les pages de la revue européenne Grand Continent

Can technological progress build shared prosperity? Perhaps the question should be, when can technological progress build shared prosperity? I am going to draw from the most recent book I wrote with Simon Johnson, Power and Progress.

The reason why we are so obsessed with technological progress is not hard to understand. Much of humanity’s lives are much healthier, prosperous, and comfortable relative to what people were used to 300 years ago. It is not hard to be impressed by the gifts that technology and innovation have brought.

But I am going to argue that this macro picture hides much more interesting variation that has important lessons for today. In the history of technological progress and prosperity that it has brought not much is automatic or inevitable. It depends critically on institutions, the type of technological progress and who controls it.

Those are questions that become even more central in the age of innovation — at least what some people view as the age of innovation — where we are surrounded by new AI products, new apps, new widgets every day. According to most statistical measures of innovation, for example, patents, there has really been a true explosion.

If we look at the US patent data, there has been a fourfold increase from the early 1980s to today. Even more notably, this has been driven by what many people view as foundational sectors that are about communication, information technology, electronics, on which many other activities in the economy build, and, of course, today, AI, and generativeAI that have captured imaginations on both sides of the Atlantic.

If you think people are becoming obsessed with AI here, in Europe, just look at the United States, where the level of excitement has reached fever pitch. In this age of innovation, AI breakthroughs, mesmerizing technological advances, the questions that I think are in the minds of many are still central.

Who will benefit from these technologies? Will they bring shared prosperity ? Who actually controls these technologies? These issues are central, partly because if you look at history, you will see very clear lines connecting the control of technologies to how the benefits are distributed, and whether they actually bring any benefits at all. Those issues should be much more central in public debate and in economics.

There is however a sort of folk theorem in economics, which, like most folk theorems, has a grain of truth and a lot of simplification or untruth in it. It has colored together with other structural sources of techno optimism, the way that many people, policymakers, journalists, opinion makers around the world and in the United States, think about technological progress and AI. It is also often the case that with folk theorems, they are part of the culture, part of the folklore. So they don’t even have a name. Simon and I gave it a name, and we called it the productivity bandwagon. The productivity bandwagon claims that there is an automatic process via which technological advances will bring a type of shared prosperity.

If indeed this productivity bandwagon is true, it doesn’t obviate the need to ask some of the questions about who will control the technology, who will benefit more, or who might benefit a little less. But fundamentally, we shouldn’t be afraid of technology. We should welcome it with open arms, because there are strong forces towards a type of tide lifting all boats.

What is this productivity bandwagon? I had the pleasure of meeting several students from Sorbonne here in Paris. I am sure this is like what you learn in undergraduate and in graduate studies. Technology improves, so our knowledge and our capability to do things.

We apply them to the production process, which means that when productivity rises, we can get more output and more goods and services from the same inputs, because we have better capabilities, better knowledge, better technology. From there on, there is a set of forces that lead to improvements for workers as well, in terms of higher wages and earning potential. This is a critical aspect because most of us still earn most of our income from the labor market — if the labor market is buoyant, wages are high. It becomes a powerful foundation for shared prosperity.

Why is it that there is this arrow from productivity increasing to workers benefiting? We could question whether when technology improves productivity rises as well, because we do have instances where improved knowledge is used for other things than increasing productivity. I prefer to leave this aside and focus on another aspect — productivity rises and workers benefit from it. Here is the basic economic argument: when firms and companies can produce more, they want to expand, and they want to hire more labor so that they can produce more. This dynamic increases their demand for labor. The labor market processes lead to higher wages. There are two claims in this statement.

First, as productivity increases, firms will want to hire more labor. Second, this demand for labor somehow translates to higher wages. Both are not unreasonable. We can find plenty of examples, including the recent 20th century, where both of these do work, that higher productivity somehow leads to greater demand for labor, and greater demand for labor translates into higher wages. But as it happens, we could also find examples that contradict each one of these channels.

That is what I am going to try to develop and explain. What I want to understand is when this shared prosperity mechanism works.

I will start with the second hypothesis, that the higher demand for labor did not lead to higher wages. I have two examples. I could think of others that are perhaps as significant for their time as the digital technological breakthroughs we are experiencing today. First, we can look at the great technological advance of the Middle Ages, which was dark in some ways, but not so dark technologically. There were a lot of technological improvements, especially in agriculture.

Windmills changed the production process in many ways, increasing productivity in some tasks by more than tenfold, perhaps as much as twentyfold. What happened? It turns out that the nobility and the high clergy reaped all the benefits and there were not much improvement in the lives of the peasants. When you think about it, it makes a lot of sense, because the peasants were in a coercive relationship in the process of serfdom and other obligations that they had to pay to the landowners. More importantly, in the case of windmills, they were completely monopolized by those same landowners. This meant that they were able to prevent anyone from opening their own windmills, or sometimes even forcing people to use their owns. Under such conditions, the kind of competitive labor market processes that would be necessary for higher labor demand to translate into higher wages are not inevitably going to work.

The second is an even sharper example. It’s Eli Whitney’s cotton gin. In the mid-1700s, the American South was an economic backwater, already lagging behind many other parts of the United States. But it was recognized that it had a good climate and the labor to grow certain crops that would be very profitable, such as cotton. But the cotton that could be grown in the South couldn’t be cleaned by the usual method. This was the machine that people tried to develop for a while. Eventually there were a few prototypes, including one by Eli Whitney, who got the patent. Contemporaries and historians agree that the cotton gin completely transformed the American South and led to a surge in cotton production. In fact, it became the largest exporter of cotton in the world, and these exports were the engine that fueled the Industrial Revolution with the British textile industry. Many people made fabulous fortunes from this enormous increase in exports. But the workers weren’t among them, because they were the enslaved black Americans who, of course, didn’t have the ability to demand higher wages in competitive labor markets. When the landowners wanted more labor from them, they simply used coercion. Large numbers of slaves were moved to the farther south, where the cotton plantations were, and conditions actually worsened for the majority of them, with little evidence of improved living standards.

Both of these examples illustrate the importance of the institutional environment, or, to put it more strongly, the role of power. That’s where the word power comes from in Power and Progress, the title of our book.

Power plays a role in how the gains are distributed and whether this critical step for the productivity bandwagon works. Power has institutional as well as other channels. Power, as we’ll see, also plays a critical role in the direction of innovation.

One might wonder if this history has any relevance to the digital age. When I said that we’re so much more comfortable than we were 300 years ago, I wasn’t dating the 300 years to the windmill, but rather to the beginning of the British Industrial Revolution, sometime around 1750, with much more advanced technology in factories starting to be used.

Some simplistic accounts of the British Industrial Revolution would say that everyone benefited from it, including the workers, so there was nothing to fear from technology. But when we look at the history of the British Industrial Revolution, a more complicated picture emerges. First of all, for much of that period, for about 100 years, workers were not doing very well, and that had something to do with what I was talking about earlier – power dynamics. Workers often had no options. They could not be represented. Unions were very much persecuted. Collective bargaining wasn’t possible. The laws were very anti-worker, including, for example, people being sent to jail for leaving their employers and looking for better jobs.

There was something even deeper than that, and it’s really about the nature of technology. The early technologies of the industrial revolution are what we now call automation, machine substitution, which today would be machines and algorithms for tasks previously performed by workers.

What we have seen is that this kind of automation hasn’t necessarily led to the optimistic productivity bandwagon type forces. In fact, that shouldn’t be a surprise, because if we go back to the first assumption that productivity goes up, and that means firms want to hire more workers, that is not an unquestionable hypothesis either.

What you learn in economics is that what companies are willing to pay for workers and how much they’re willing to hire is related to the contribution of labor to production. This is what economists call marginal productivity or marginal productive labor. By contrast, when we say productivity is rising, we mean how much you produce given the amount of labor, which is average productivity.

There is reason to believe that average productivity and marginal productivity are moving. One goes up, the other goes up. But there are also reasons to suspect that they don’t. To illustrate this, I often use a joke that captures the essence of this, which is a utopian or dystopian view of the future — it says that the future factory will have two employees, a man and a dog. The man is there to feed the dog, and the dog is there to make sure the man doesn’t touch the equipment.

If that’s your idea of utopia, that’s fine. It may not be so good for labor precisely because this joke’s essence is that the productivity of the bandwagon doesn’t work. You can increase productivity by going more towards that factory, or that factory’s equipment gets better, and you now produce twice as much output. You don’t need the man and the dog, they are completely dispensable.

If productivity increases twofold, no factory will rush to hire more men and their dogs. What this example essentially captures is equipment that eliminates the need for workers and drives a wedge between marginal and average productivity. This is exactly what we saw in the first half of the British Industrial Revolution, for a period that probably lasted 90 or even 100 years.

It was not until the late 1840s that we began to see consistent wage increases and improved conditions for workers, not coincidentally with union recognition and bargaining for better wages and conditions. This is a technological story as well as an institutional one.

You might not be so interested in these stories because you think they are history. Perhaps some tech gurus used the Industrial Revolution to justify their disruption, but we can forget about it. We live in modern times that are different.

Are modern times really different? Yes and no. There are some remarkable similarities and remarkable differences. The differences actually can be seen especially in the fifties, sixties, seventies in the United States, in France, in Germany and many other countries.

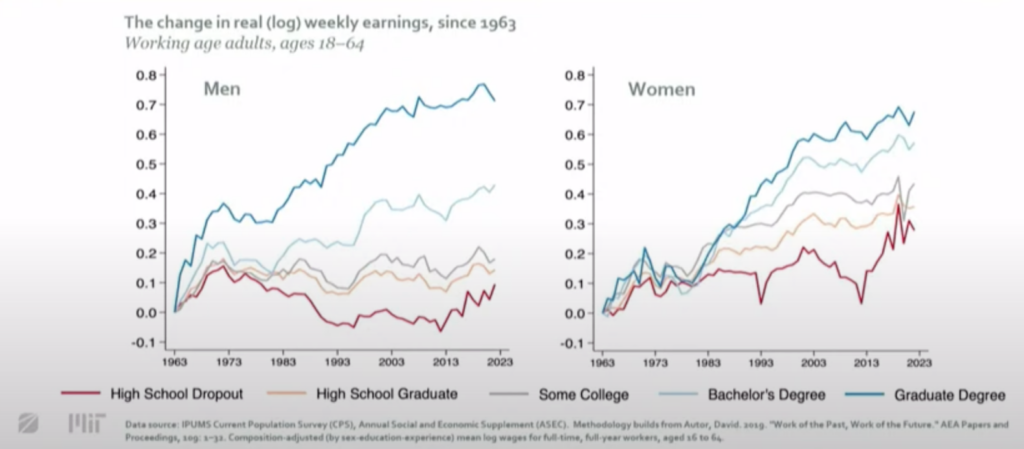

If we look at data from the US, in the chart below, we see inflation adjusted wages for men and women, and five education groups, all the way from workers with a highschool dropout to those with a postgraduate degree.

The data are normalized to zero so that we can follow the cumulative increase in real wages. What we see is that from 1963, when these data begin, through the mid to late 1970s, there is a period of remarkable shared prosperity. All ten demographic groups experience rising real incomes and relatively rapid growth. If we were to extend this series with other sources back to the 1940s, we would see even faster growth, and even faster for the less educated groups. It’s really a period of relatively equal growth, where the bottom of the wage distribution is growing and growing very fast. The average growth between 1949 and 1975 in the United States is about two and a half percentage points a year, adjusted for inflation, which means that in 30 years people are essentially doubling their real incomes. We can see that with that kind of income growth, you can get into the middle class pretty easily.

That’s the kind of shared prosperity experience that many countries around the world, had, especially in the West. In France, those were the glorious three decades, but they were glorious in other parts of the world as well. Around 1980, perhaps a little earlier, we begin to see a very different pattern. There is a jarring divergence between the top and the bottom. The reason I’m looking at this as cumulative is that we can see that for high school graduates and high school dropouts, real incomes actually decline over this period. So for about 30 years, a large portion of the population, far from benefiting from economic growth, actually saw their real inflation-adjusted incomes decline. There are similarities with what we see in the US, in other countries as well, such as the United Kingdom, where notable inequities accompany rapid, disruptive technological and social change.

But this pattern is not the same everywhere. If we look at the data for Sweden over the same period — or at least the second half of that period — wage inequality is actually declining. Sweden is subject to the same technologies, the same globalization, but it paints a much more complicated picture. Wage inequality is falling even as overall inequality is rising, partly because of changes in hours, capital income, and other factors that may or may not be affected by globalization.

The idea that I keep coming back to is that there are some decisions that different countries make differently about who’s going to win and who’s going to lose. All of this begs the same question. How did shared prosperity happen? Or shared growth? How was it that in the decades after the Second World War, in the United States, in Europe, in the United Kingdom, there was relatively evenly distributed income growth? Or how did it take shape in the second half of the 19th century, in the British industrial revolution? And how was it reversed in the 1980s?

My account is exactly related to the two pillars of the mechanism of shared prosperity that I have highlighted. Power that is equally distributed between workers – or at least not very unequally distributed between workers and businesses – so that we don’t have the kinds of situations that we had with European serfdom in the Middle Ages, or with enslavement in the American South, and a direction of technology that doesn’t just automate, but also creates other technological possibilities for increasing the productivity of labor and the contribution of labor to the production process. We can see this, for example, in the automobile industry in the United States, which was already sowing the seeds of postwar developments in the 1910s.

The image above is from one of Henry Ford’s early factories, the River Rouge complex in Michigan. Ford pioneered assembly lines, electric machines, high productivity, and mass production. We can already see that in the Rouge complex, which is a flat organization, cars were being moved around and there were decentralized electric machines doing things that previously could only be done by workers. Automation is not a new phenomenon, it’s not just something we see with digital technologies. Nothing I’m saying here is against automation, but what you see in the Henry Ford factory is that automation was not the only game in town. It was combined with a lot of new technical tasks for workers.

The workers we see around the cars perform critical functions, and there is actually an army of other workers in the back doing repair, maintenance, accounting, engineering, clerical work. That is why, as mass production began, employment in the Ford factories and employment in the auto industry boomed. Automation was coupled with other technologies that created new tasks for workers, so they were reassigned to more technical, higher-paying activities as some of the earlier activities they had done were taken over by machines.

This balance between new tasks and automation is both organizational and technological. You have to have the technologies to do it — it is about the direction of the technology and the organization.

Henry Ford decided to do this not because he was a friend of labor, far from it, but because he saw that increasing labor productivity was the best way to increase his own bottom line. He wasn’t alone. The auto industry was also a hotbed of union activity.

Below is a picture of the United Auto Workers sit-down strike at a General Motors plant. There were earlier sit-down strikes and other strike activity in Ford plants as well. The strengthening of unions was an important part of workers getting a fair share of the productivity increases, and the auto industry was a leader in that. Unions spread from the auto industry to other industries in the years that followed.

These two forces are remarkably similar when we look at the second phase of the British Industrial Revolution, which also saw a change in the direction of technology, away from just automation to ways of increasing the productivity of labor and a more balanced distribution of power within factories and within societies.

If these are the two pillars that underpinned shared prosperity, you won’t be surprised that my narrative says it was also their undoing, which is at the root of the huge increase in inequality and the very unshared nature of economic growth in the United States and many other industrialized nations over the last four decades.

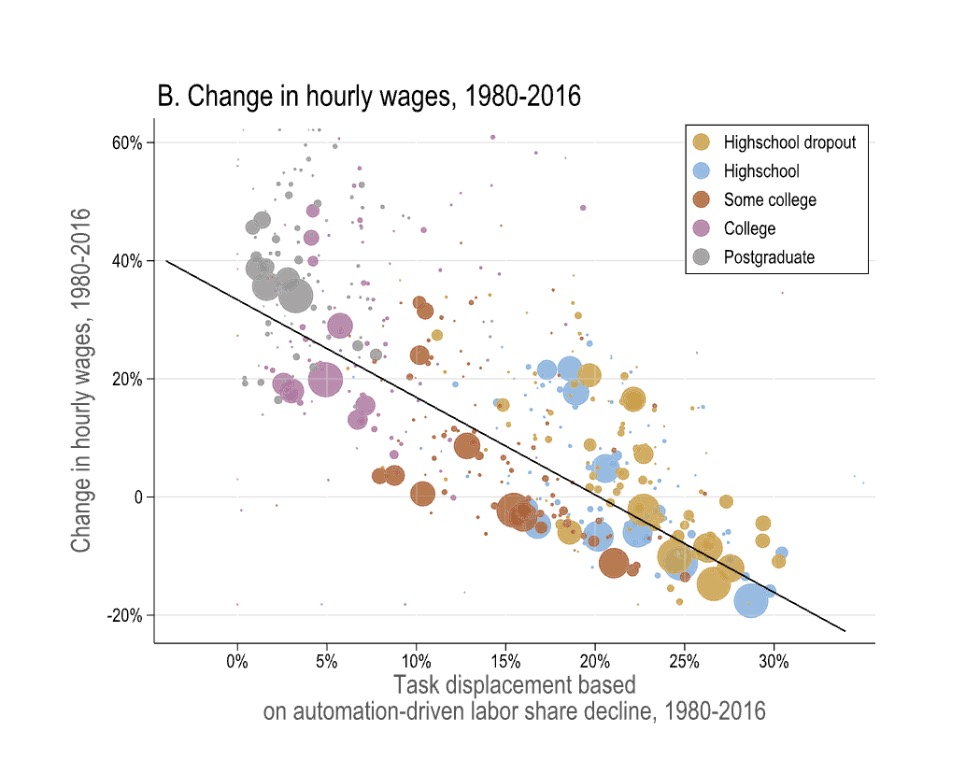

The image above show what a car factory today looks like. It has gone much farther in automation, but you don’t see the workers like you did in the Ford factory. There is only one person, and he probably has a PhD. The manual workers used to do the production have significantly declined in numbers because robots have been very much targeted to automation, with no corresponding changes in other technologies creating new tasks for workers. Now, this is not perhaps a statement that you will have seen, because many of you may have encountered the increase in inequality in the United States and may have heard about other potential explanations. I will look at one more chart to underscore the importance of automation. It is based on my work with Pascual Restrepo, where we look at wage inequality changes in the United States and relate them to automation. Each dot represents a certain detailed demographic group and rather than showing the time series of the up and downs of inequality, on the vertical axis, I am plotting the change in the real earnings of each demographic group from 1980 to 2016.

About half of the dots are below zero. This underscores the uneven nature of economic growth. About half of the demographic groups haven’t really benefited from this spectacular growth in the digital age. More interestingly, on the horizontal axis, I have our measure of automation, which is essentially what fraction of the tasks that a demographic group used to perform have since been automated. For many groups with low levels of education, high school graduates, especially young men, they used to do a lot of blue-collar work in companies like Ford or General Motors. We see a remarkable relationship between automation and inequality, accounting for about 60% to 70% of the changes in wage inequality.

My point is that how we use and develop technology and how we organize around it is very much a matter of choice. It is in that choice that institutions and power become particularly important. There are many changes that have happened since the 1980s, but I want to focus on two of them.

First, the labor movement in the United States became much weaker. This was perhaps inevitable, since deindustrialization had already begun a process of weakening unions. But it got an extra kick when President Reagan fired the striking air traffic controllers, because then many other companies took a cue from him and adopted a much harder line against labor, leading to a faster decline in union power.

But another trend is just as important. It’s not just technology and hard power that matter. The ideas and norms of powerful actors, such as CEOs or business leaders or politicians, are also very important. The model that Ford unwittingly developed is what some institutional economists in the early 20th century called welfare capitalism. Firms do well and then they share the gains with their workers. They share the gains because unions forced them to. They shared the gains because they think that’s going to motivate the workers and they share the gains because that’s just a fair thing to do.

A different kind of ideology emerged in the 1980s. Like many ideological revolutions, it has many fathers. I will single out Milton Friedman because he was very vocal about it. His most famous work was not in an academic journal, but in the New York Times Magazine, where he argued that the only social responsibility of business was to increase shareholder value, which meant, in particular, that business leaders should be encouraged to reduce what they pay to labor. If they don’t have to, why should they pay more? That means more for shareholders and also a drive to reduce labor costs, which is the most important component of costs, which of course means automation. Corporate ideology leads to more automation. One bulwark against that would have been the unions, but the unions are in decline, so they can’t resist. We have these two forces combined, but there is a third force that is perhaps, at least in my estimation, not inferior to the other two. You may want to automate as much as you want and have no resistance, but if you don’t have the tools to automate, you’re not going to be very successful.

There was a willing industry to provide those tools: the tech industry, especially in the late 1970s and 1980s and got into a mindset that we see reinforced today. It is very relevant, at least in my assessment of AI, which is about what technology – especially digital and IA — should do.

It goes back to the thinking of Alan Turing, a real mathematical pioneer. He was trying to conceptualize what it is that machines should do, can do, and how it compares to the human mind. He came to the conclusion that computers work like the human mind, or perhaps the human mind works like the computers that he had in mind, and that it was therefore a desirable process for computers, digital tools, to take over more and more tasks from humans as they got better. Ultimately, if you have the universal Turing machine, it can do all the cognitive tasks that the human brain does, because he thought that the human brain is nothing but a Turing machine. That was the perspective that the AI community swallowed hook, line, and sinker.

That venerable group of gentlemen who christened the field of AI at the Dartmouth Conference in 1956 had exactly that perspective. AI is the branch that should develop autonomous machine intelligence. Machines that do things like humans and do them autonomously, meaning that they should do them in a self-acting way.

If you have that, it means a very strong force toward automation. If machines are already doing things like humans, and they’re getting better and better, well, let’s give them more tasks and take them away from humans. And it doesn’t create a natural driver to lead us to more new tasks for humans to expand human agency, human capabilities.

The problem is that this perspective, at least before the age of AI, has not been that successful. The age of innovation is upon us, led by digital tools but the productivity gains aren’t there. If we look at the economist’s favorite measure of productivity, total factor productivity growth, the digital age, is much slower in terms of productivity growth than earlier decades. This is not just confined to the United States and we see the same pattern in other industrialized nations.

The reason, I think, is this overuse of automation, which, as I’ve argued, is problematic not only because of its distributional effects. If we overdo automation, if we substitute machines for human tasks when we shouldn’t, then we’re not really going to get the productivity benefits. We’re going to get a lot of this kind of lazy automation that I called “so-so automation”: a few more dollars for companies because they’re saving on labor costs, but no productivity revolution, no improvements in product quality. It’s like automated customer service or self-checkout lines that don’t work.

Will AI change that? I don’t think so, but I will come back to it in the conclusions.

But talking of digital technologies and AI, just as an economic phenomenon isn’t enough. They are information tools which means they influence every aspect of our social lives, including democratic and political participation.

Surveillance is just one aspect of what, how AI and other related tools, especially computer vision tools, are going to affect the political landscape. It’s much broader than that because it’s about information control. Everybody, at least in the West, recognizes the problematic nature of the image at the bottom, which is an example of the social credit system that’s already been implemented in China, where you have to go and check your social credit before you can go to the next machine and buy a ticket.

But what we have here is not much better. Instead of the Chinese government controlling information, we now have private companies collecting, controlling, and processing that information for their own purposes. And if the other arguments I’ve made say that there is no necessary overlap, no complete alignment between the interests of corporations and the interests of workers and society at large, why should they resort to information control? This is an issue that requires a much longer discussion.

I want to conclude by talking about something slightly more hopeful. I have pointed out the problems associated with changes in institutional power and changes in the direction of innovation. I don’t want to give the impression that this is a trap from which there is no escape. As I have emphasized, what I really want to stress is that choice is critical. We choose what kind of institutions we live under. We choose the direction of innovation – or at least we have some say in theory about its direction. What’s wrong with this picture is that it’s just emblematic of us as a society; we’re giving up that choice and leaving it to a debate between just two somewhat flawed individuals to decide which one is going to dominate the future age of AI.

Where is society? Where are the workers? Where is democracy? I think that is a critical question, and that can of course not happen unless we have the politics of shared prosperity working, which means countervailing powers. Welfare capitalism didn’t happen by itself. It happened with unions with civil society organizations. Critically, the key for shared prosperity is the direction of innovation. It is impossible to build shared prosperity if all tools push for automation and centralization of information in the hands of companies.

But there is a choice. It is very interesting that at every stage of the digital revolution, there were people who believed that it was feasible and likely that digital tools would play a decentralizing, democratizing role. For example, Ted Nelson at the beginning of the PC age, was a political activist and a technologist who thought that large companies were killing the technology because they were exploiting it the wrong way and a different way was possible. He was optimistic that it could be reached. Ted Nelson never came up with technological breakthroughs, but actually several other people did and they provide a much better template for the kinds of AI that we want, in my opinion.

When at the same time as Alan Turing was writing about his views on computers and the future, Norbert Wiener, an important mathematician and engineer, was writing about the same subject. As early as 1949, Norbert Wiener was worried about robots automating work, what that would imply for workers and wages. He outlined a different view of what technology should do, which in our book, we call machine usefulness to contrast it with machine intelligence. Machines should be at the service of humans, expand human capabilities and human agency. Norbert Wiener himself was a theoretical engineer, never came up with technologies to do that but several other people did. Douglas Engelbart and his students in the 1950s and sixties already made many breakthroughs which we take completely for granted today. The mouse, that was Engelbart’s mouse, menu driven computers, hyperlink, hypertext, all of those came from him and were expended by his students. They did not come out of a vision where we should automate at all costs. In fact, Douglas Engelbart also wrote about human machine complementarity.

Joseph Carl Robnett Licklider, who could be viewed as the father of the Internet because he actually designed and supported the development of it in the ARPA, had exactly the same idea. He called it man machine symbiosis. So these were the thinkers who thought that we could expand tools in a way that would be useful for humans to do more.

AI, if done right, could go in that direction, because, as an informational tool, could actually give more capabilities for many people rather than just automation. But, related to politics of innovation, it’s not the direction that we are going in. All of this might strike some as wishful thinking that somehow I am saying, well, all of these amazing geniuses in Silicon Valley don’t know what’s best for society and we here as analysts from the outside can have a different view of what’s perhaps better. Government regulation and societal pressure could change that. Some people, many economists would say that’s just fanciful thinking, but it’s not as fanciful as you might think.

One example illustrates it very powerfully. The energy sector. Those geniuses did what they thought was best, which was build and build more fossil fuel technologies. They didn’t take that into account that fossil fuel technology is very profitable for them, but were not going to be good for society. It took a lot of government regulation, subsidies for green innovation, and societal pressure to change the picture.

As recently as the late 1990s, early 2000, renewable technologies were 20 times as expensive for producing electricity. But we had tremendous technological progress and learning by doing.

Today, they are actually cheaper than fossil fuels for the electricity grid.

citer l'article

Daron Acemoğlu, The Future Of AI Depends On The Choices We Make, Oct 2024,