US And The China Problem: A Lost Archive Of David Galula

18/10/2024

US And The China Problem: A Lost Archive Of David Galula

18/10/2024

Voir tous les articles

Voir tous les articles

US And The China Problem: A Lost Archive Of David Galula

We are preserving all misspellings and strike-throughs from the archive. Brackets indicate where letters, words, or passages were added by hand to the typed document (Patrick Weil).

William C. Bullitt papers

Group No. 112

Group No. 112

Box no. 31

Series No. I

Folder No. 10

May 26, 1950

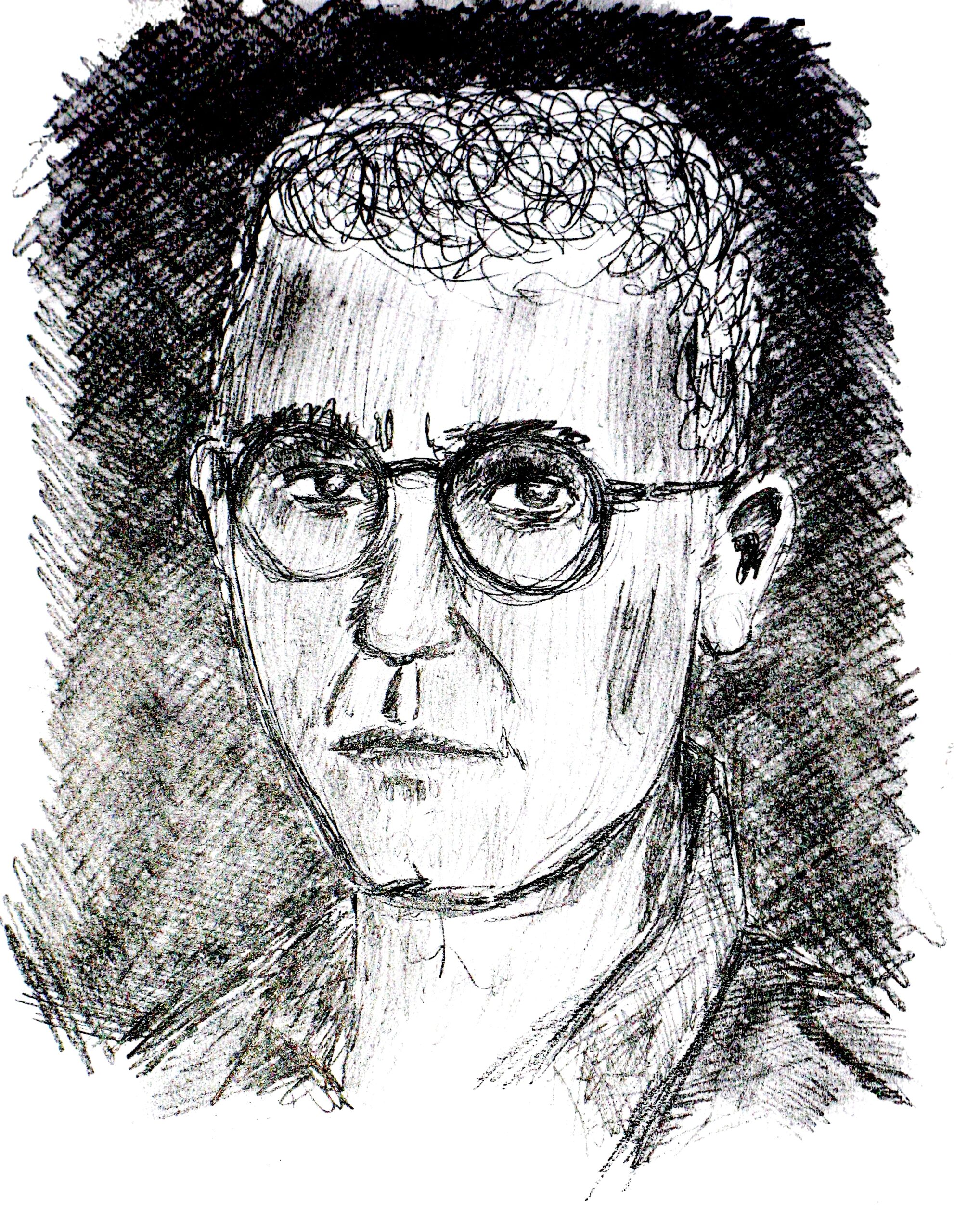

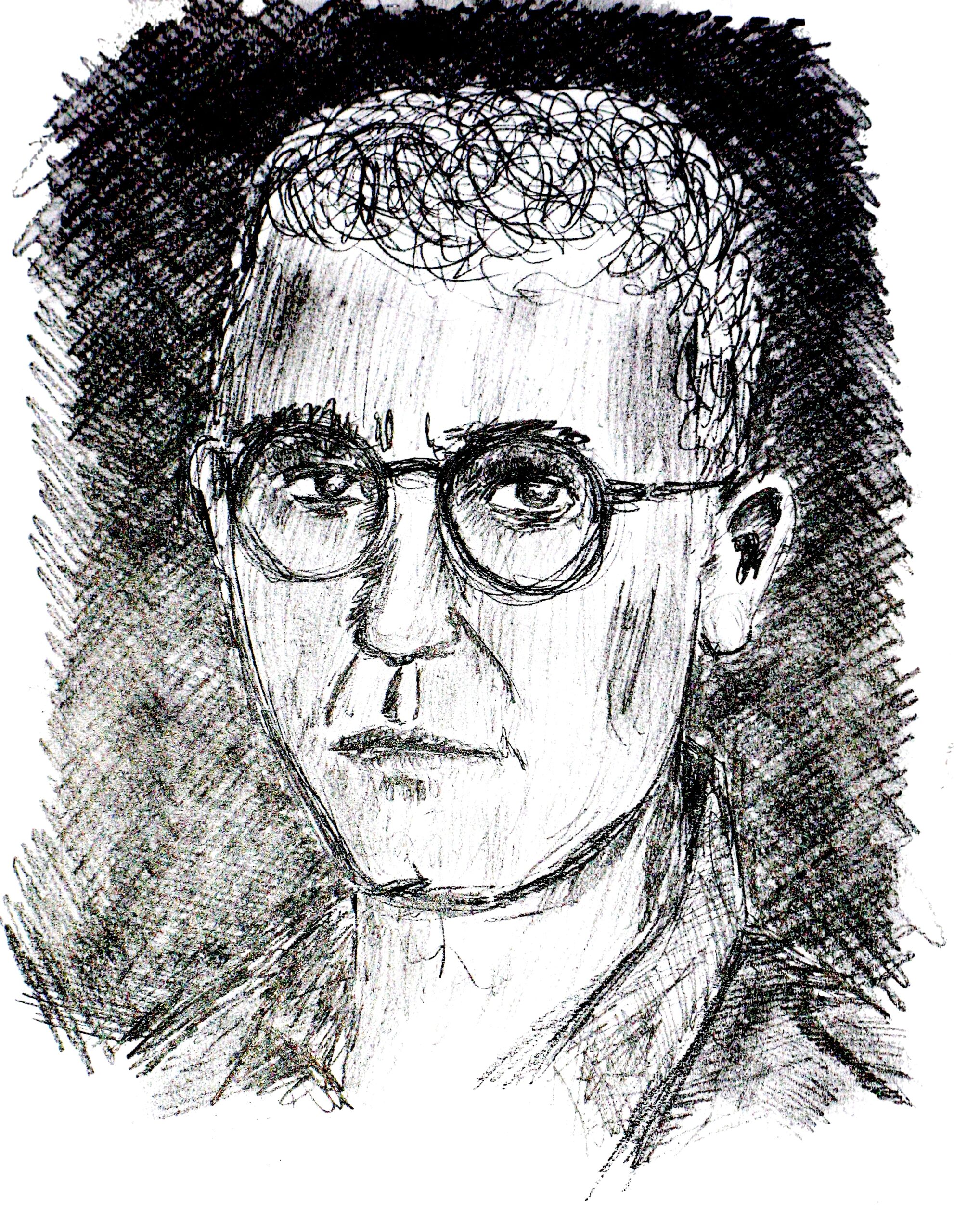

Captain D. Galula

French Military Observer

UNSCOB, Salonika, Greece

My dear Captain Galula:

I was intensely interested by your letter which has just reached me. I value your opinions in the highest degree, since everything that you predicted to me has come to pass –unfortunately. If it were possible to have such a policy as you suggest carried out, I would attempt to support it; but my opinion is that there is not the slightest possibility that the American Government may be persuaded to take such a course.

Please do not forget for the future that it will always give me great satisfaction to see you. Perhaps our paths may cross once more in this disordered world.

With every good wish, I am

Yours very sincerely,

William C. Bullitt

William C. Bullitt papers

[Read the analysis by Patrick Weil and Jérémy Rubenstein]

Captain D GALULA

Salonika, April 26, 1950.

French Military Observer

UNSCOB, Salonika, Greece

Dear Mr. Ambassador,

Knowing your interest in Chinese affairs, I would like to send you a study that I wrote a few weeks ago. It is not intended to be published, the publicity would only harm the line of action I am proposing. I presented it to the National Defense Staff who, though sceptical that the various interested governments would adopt my argument- including ours-, nevertheless authorized me to submit it to you, acting on my own responsibility of course.

Shortly after my return from China, in the spring of 1949, I was posted to Greece as a United Nations military observer. I therefore was able to witness yet another civil war. I was expecting to find in this country a somewhat similar situation to what I had seen in China; luckily, the experience I gained in China allowed me to quickly recognize the significant weaknesses of the Greek communist uprising that ultimately lead to its defeat. Without delving too deeply into the subject, I can attribute this defeat to the following reasons:

– The Communist Party of Greece did not enjoy the support, either active or moral, of the majority of the Greek population. To a population worn out by years of war and occupation, this party was offering a platform that essentially only consisted of promises that had yet to be fulfilled, and whose relevance was not clear to everyone. Furthermore, its affiliation with the Bulgarians, “the enemies of old”, flew directly in the face of the population’s patriotic sentiments, sentiments which are still very strong in a country that has not stopped fighting for its independence and against unruly neighbors. Consequently, the Communist Party of Greece had to quickly renounce any nationalist ambitions. Without the support of the population, and rather due to its hostility, the Communist Party of Greece was unable to carry out any real guerilla operations; the so-called Greek Communist guerillas were not, as in China, groups from the countryside that formed more of or less spontaneously and who took action as soon as national troops were busy elsewhere; in fact, it was small commandos, recruited from the party’s “hardliners”; they took advantage of the country’s particularly rugged terrain to infiltrate the rear of the national troops and to harass them for as long as they could sustain by relying on their own means. And whereas the Chinese Communist Party snowballed, the Communist Party of Greece saw its initial forces rapidly dwindle and it was reduced to relying on forced recruitment in order to maintain its force.

– The Chinese Communist Party primarily resupplied from the adversary and therefore found in China itself, mostly, the necessary means to carry out its operations. For the Greek communists, it was impossible to apply this method because the national soldier was not inclined to surrender without a fight. The fate of the Greek communists was therefore linked to the various provisions provided to them from satellite countries, from Romania and Czechoslovakia and Albania. The day that Tito dissented and banned the transit of supplies through his territory, the Greek communists were lost.

– Finally, the Greek government, despite its obvious faults and flaws, was still a government. I have not noticed here, to a comparable degree, the corruption and negligence that paralyzed the Chinese national government.

It is for these reasons, in my opinion, that American aid bore fruit. Without this aid, the communists would have probably won; but without the fundamental hostility of the population to the movement and communist ideals, this aid would not have made a difference.

The Greek military problem is now handled, at least when it comes to the Cold War. Next to the giant problems posed by China, it has never garnered much interest. It’s for this reason that ,despite being so distant from the Far East, it is with great interest that I have continued to follow the evolution of the situation in this part of the world and the debate it causes in your country, which it affects more directly than any other Western nation. I was surprised and disappointed to see how little, among all those who criticized the State Department, criticized it in a constructive way, meaning proposing a new and active policy. Some suggested continuing to increase aid to the nationalists, as if this policy had not already been condemned a hundred times over by events. And since the State Department came up with its new policy on the Far East, no one has yet to criticize it as insufficient.

If we weren’t all of us, American, English or French, in the same boat, it certainly would not be my place to do so. But since your country is the leader of the coalition of Western countries and your government’s decisions affect all of us, I feel somewhat justified in making my views known to the American government. It is for this reason, Mr. Ambassador, that I am taking the liberty to send you, my study. I have no expectation, of course, that the policy I am proposing be enthusiastically adopted and immediately applied. It is possible that I am not even the first person to propose it. At the very least I will have relieved my conscience, which has been preoccupied by how few of my compatriots or yours have any idea, however basic, of the consequences a victory for the Chinese communists would have, especially if they ally themselves with the USSR. And perhaps my study will have sufficiently interested you that you one day decide to open their eyes by publishing an article about it in LIFE.

Yours faithfully.

*

At this current moment, what is the most pressing and most serious problem posed by communist China to the Western powers? It is preventing China from fighting in the Soviet bloc because, within a few years, the Cold War will have transformed into open war.

This is the most pressing problem due to the imminent nature of this third world war, which so many indications point to happening in less than five years. Indeed, it is difficult to see by what miracle the current political tension could be resolved otherwise. It is easier to see, on the other hand, the end point of the arms race the two sides are already engaged in. While, in a first in contemporary history, a nation such as the United States could dedicate enormous amounts of money to its defense without at the same time upending its peacetime economy, the USSR cannot sustain the pace of this race without major sacrifice for its normal economy. Sooner or later, the USSR will have to either surrender or launch a military campaign. With what little we know about the Russian leaders, this latter choice seems the most likely.

It is also the most serious problem. We have reasonable odds at defeating an isolated Russia. Ultimately, it is a question of industrial and scientific superiority –which is still in our favor– and our moral superiority; on this last point, the USSR is losing ground every day in Europe. A war that would pit us against Russia alone, by its very nature, would allow our superiority to come into play; any war would remain primarily a technical one, a war of materiel. As vast as the Soviet territory is, the sources of this country’s military power, such as atomic bomb factories, airplane factories, petroleum refineries, etc, are objectives subject to our actions.; breaking them up does not prevent the USSR from being vulnerable to a scientific war: atomic bombardment, radio guided missiles, etc… But if China sides with Russia, the war’s outcome will be more than doubtful, on the one hand due to the addition of the tremendous forces that it would grant the Soviet bloc, and on the other hand because its intervention would change the nature of the war. Even taking into account the fact that China will not have had the time to develop its industrial potential, in this respect it represents an invaluable ally for the USSR.

China would relieve its ally of the need to actively fight on two fronts; the American Navy could undoubtedly block the development of any major Sino-Soviet offensive in the Pacific; on the other hand the Western coalition cannot lead a major offensive on Chinese or Siberian soil; such an operation would require many more troops in this theater than was needed to hop from one island to another during the last war. We can therefore safely assume the neutralization of the Pacific. But how do we stop the invasion by China of the South-Eastern portion of the Asian continent, Indochina, Siam, Burma, Malaysia, India? Such an offensive is currently possible for the Chinese communist armies, supported with a minimal amount of logistical aid from Russia. In this theater, our technical superiority would not come into play; short of using biological warfare resources, supposing they exist, we would be forced to wage a war of infantry, at a moment when they are in short supply, and against a generally hostile population. An alliance of China and Russia would mean that in Asia, moral superiority [will be] shiftse[d] to the Soviet camp. While communism is currently losing ground in Europe, it is gaining ground at a furious pace in Asia where it is associated, in the eyes of the population, with a nationalist and anti-white movement. With their slogan “Asia for Asians”, the Japanese have tried to take advantage of these sentiments; they hadn’t entirely succeeded because they didn’t have an ideological system to offer. The Chinese, this time, are proposing one that is so cohesive and so effective that an adversary as powerful as the United States couldn’t stop their success. The difficulty of acting in this South-east Asian theater will perhaps force us to neglect it for a time and to concentrate our means on the primary rival, the USSR. The fact remains that, once Russia has been defeated, we’ll be faced with a costly fight in Asia, unless we wish, after a total war, to renounce total victory.

To mention yet another advantage of this alliance, communist China will provide the USSR an inexhaustible manpower, thanks to its 450 million inhabitants; the exploitation of [t]his manpower will only be limited by the ability to transport it. Let us note, incidentally, that that China’s economy would not suffer, on the contrary, unless the population of this country is cut down by about ten million men. Furthermore, we run the risk of seeing this manpower appear in the conquered countries of Western Europe, in the form of occupying troops; these Chinese troops, who are experts in the art of guerilla warfare and consequently of counter-guerilla warfare, unable to be reached by our propaganda due to the language barrier, will be in charge of maintaining security along the Russian rear lines and will therefore free up many Russian troops for more active tasks.

Does this not neutralize our industrial and scientific superiority? One could think that the consequences of the Sino-Soviet alliance described above are exaggerated and challenge the current reality of the famous yellow peril. Yet these consequences are a far cry from the possibilities of such an alliance. It would be dangerous to underestimate the current dynamism of communist China. In 1946, when MAO TSE-TUNG’s army was less than 300,000 loyalists facing a million and a half nationalist soldiers, how many people would have bet on a communist victory? Against the 650 million men of the Sino-Soviet bloc, the Western powers have 250 million men, with perhaps 60 million more in Europe if these latter are not quickly engulfed by the Russian tide. This means that if our technological superiority is neutralized, we [are] defeated by pure arithmetic. The danger of such an alliance is so great that we must do everything to prevent it.

One point is certain even now: the communist regime is solidly in power in China, and we are wasting our resources in vain if we are looking to defeat it by supporting what remains of the nationalist government; this government is dead from its excesses as much as from blows from its adversaries. An immediate war, supposing we were to accept the idea, is not a solution either: it would hasten this alliance that we wish to prevent; the Chinese communists have not ceased to proclaim their allegiance to Kominform and there is no reason to think that they would change their position given the current state of things. The policy of a cordon sanitaire around China, paired with military aid to its neighbors, has just been recommended by Mr. ACHESON. This policy, which now forms the basis of American policy in the Far East, is insufficient and does no better to resolve the main problem. No cordon sanitaire will halt the communist ideology’s penetration in Asia where it will be propagated by the Chinese who already have large colonies to draw on. Fighting communism by improving the quality of life of the population is a long-term endeavor and time is not on our side. Finally, no Asian country, except perhaps Japan [,] who it would be unwise to fully trust, is organized enough and ripe to form a solid military barrier against China once war has broken out. Ultimately, the only solution is to insert a wedge between China and Russia.

There are a few good reasons to think that with time, a schism could happen by itself between these two countries. Beneath ideological, and consequently somewhat abstract, ties which unite them, it is easy to detect deep-rooted seeds of discord. One of the major factors behind the Chinese communists’ rise to power was the active support of a large part of the population; in fact, propaganda was their primary weapon. The Chinese communist leaders were always extremely careful to not fly in the face of the sentiments of the majority of the population; in June 1948, for example, having noticed the strong opposition of farmers in HONAN to agricultural reforms, they announced that they would suspend this reform until the farmers, who would undergo a deeper political education, would willingly accept it. One point in particular they afforded the greatest attention to was to appear to be true champions of Chinese nationalism in the face of “American imperialism” and they were in large part successful. Due to this intensive propaganda, a large number of Chinese have now become aware of political problems they were unaware of. And by the fact that the Chinese communists depended on the success of their propaganda, they are now prisoners of the public opinion that they helped created. Until now, pure xenophobia was the underlying basis of Chinese nationalism; this xenophobia was always directed towards the most obvious stranger on Chinese soil. Yesterday, it was directed at the Americans, however pure and disinterested their intentions; Chinese students, fed by rice and flour given for free by the United States, were the most violent towards them. If the Russians become [“] the most visible [”]strangers, it is likely that they would at the same time become the favourite target of Chinese xenophobia, despite all the efforts of the local communist government to fight this traditional Chinese mindset.

Another seed of conflict lies in the fact that the Chinese communists rose to power without needing –and without receiving—significant aid from the USSR; they were not installed to power by the Red Army, as with the European satellites. Its therefore seems natural that they feel more independent regarding directives coming from Moscow. As long as the interests off the Chinese communists and Russia coincide, Beijing and Moscow will walk side by side. But what will happen when these interests diverge? Mr. ACHESON recently alluded to Russia’s plans to annex Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, and SINKIANG; it is still too early to confirm that this annexation is a foregone conclusion and Mr. ACHESON’s declarations perhaps had no other goal that to alert the Chinese public about the USSR’s potential ambitions. Whatever the case, the USSR extracted major concessions in the former Chinese regime’s territories; would it not demonstrate a certain reluctance to make these concessions to China, even if it had become communist? Russian and Chinese interests also risk diverging in another area: of these two countries, which one will become the leader in expanding communism throughout Asia? China seems to be the most natural leader because it is an Asian nation and because its historical prestige shines today more than ever. Will the Russians trust their Chinese allies to the point of allowing them to lead their expansion project? That is doubtful as the Kremlin’s suspicion is as traditional as Chinese xenophobia; moreover, Chinese communist orthodoxy remains to be established.

Furthermore, for more than a century, China has opened its coastline while it gradually closed off its mainland. This phenomenon was not due to an accident of history, it is geography, which is much more imperative, which brought this about. It cannot be artificially reversed in a near future, the Chinese communist leaders would notice sooner or later. If spiritual sustenance could continue to come from the East, it is only by the sea that China could satisfy its economic needs. It will therefore remain attached to this Western world and in order to maintain its trade relations with it, China will demand a certain degree of freedom from the USSR. Should this freedom be refused, it will result in a new cause for conflict.

These seeds of conflict, however, will not spontaneously develop if Russian leaders are intelligent enough to understand that they cannot allow themselves to treat China the way they treated their European satellites. China’s future direction will be determined by Russia’s attitude. If they display open-mindedness and tolerance, if they treat China as an equal partner, their alliance will not break apart on its own. If Russia proves to be brutal and ruthlessly intervenes in Chinese affairs, that will be the end of this alliance. For us, we could wish for nothing more than to see the USSR become bogged down in the Chinese quagmire; this would be its definitive end. It is not yet possible to determine the USSR’s attitude in its relationship with communist China. This detail holds major importance and should be given the highest priority from interested services, whether diplomatic or not.

Let us assume the worst, meaning the USSR choosing a policy of tolerance. Do we have any means to aid in bringing these latent seeds to bear fruit? Can we poison these countries’ relationship, for example by forcing the Russians to ruthlessly intervene in Chinese affairs, forcing them to become [“] the visible strangers[“] and thereby sentencing them to turn their backs to the Chinese people? Through propaganda alone, we will not get far; our writing, press, books, pamphlets, will not penetrate the “bamboo curtain” any more than the iron curtain; we can therefore wait until the Chinese press is under total control of the communist party; as for radio shows, they will run up against the most simple and effective obstacle: a small minority owns receivers Given this, the only means available is the “bamboo telegraph”, meaning the spreading of rumors and news by word of mouth; this method can only work if the Chinese people are opposed to the authorities in power; this was the case under the Japanese occupation but for now, the communist party continues to benefit from the support of the majority of the Chinese. It is clear that we also cannot rely on China’s candidacy to leading the expansion of communism in Asia. What means is left to us? A single one, and luckily it is a powerful one: the economic blockade of communist China by all the western nations.

After twelve years of foreign and civil war, China has desperate need of economic aid to regain its pre-war prosperity. But returning to the prosperity of the past is not the goal that MAO TSE-TUNG and his entourage have set; they have laid out ambitious plans for the rapid development of industry and agriculture in China; having given great publicity to these projects, they are obligated to see them through, if not in a spectacular fashion, at least enough so to show some signs of progress to the Chinese people.

If the Chinese communists have regular access to western means of production, there is no doubt that through the effect of these regular exchanges alone, China will reestablish itself quickly and progresses as it did before the war. If it is deprived of these sources, where will MAO TSE-TUNG find the great economic support that he needs? Only in Russia and he will demand it. Could Russia grant them this? It already has its own massive needs to meet: rebuilding its devastated territories, the arms race, and perhaps, as a last priority, increasing the production of consumer objects in order to give some encouragement to its population who has been worn out by so many years of hardships and privation. If these obligations hadn’t been so imperative, would Russia have exploited its satellites so brutally, thereby losing a good deal of sympathy among their populations? The Titoist heresy would undoubtedly not have happened if Russia had not monopolized Yugoslavia’s production with no compensation.

Suppose that, however improbable it may seem, Russia grants the aid to China anyway. In this case, the blockade will have weakened Russia’s economy, which is no small feat.

If, on the other hand, Stalin refuses to help his colleague, MAO will face a dilemma: either he can make do with essentially China’s own resources and have serious difficulties with the Chinese people; or try to get help from the West and, in the second case, have to contend with his Russian comrades. Because we will then be in a position to dictate our terms.

It is certainly possible that MAO TSE-TUNG evades the logic of this dilemma; events sometimes make a mockery of logic. If the economic blockade has no other effect than to reduce the military potential of a likely enemy, it will have not been entirely in vain.

There are, of course, a number of strong arguments against the idea of a blockade. First of all, is it possible to maintain it? It is not just a matter of establishing a corvette curtain off the Chinese coast. The blockade begins in our ports, with an embargo on exports to China.

Won’t the blockade upset the Chinese people? Of course, but who will they be most upset at if not the Russian allies who won’t help them during this crisis? The Chinese Communists themselves have seen the extent of the aid given to the nationalist government by the United States; they will not fail to make the comparison. Moreover, by maintaining silence about the blockade, by avoiding drawing attention to it in our press and propaganda, we could partially reduce the adverse moral effect it could cause in the minds of the Chinese people.

Would the blockade force the Chinese communists to launch a military campaign to procure the products they need? It is a risk they would have to take, though it seems unlikely. It is above all supplies that they would find in neighboring countries, and they are not the supplies that China needs; it needs industrial products that it cannot procure from Southeast Asia. And it will always be possible to relax the blockade when tensions become dangerous.

It can also be argued that the blockade will deprive us of markets essential to the prosperity of our economy. This is true, and it’s one more sacrifice we must make. If we believe that the third world war is a far-off and problematic possibility, then let’s reduce our military spending and contribute more to our prosperity. This point, moreover, deserves to be examined from another angle. An examination of China’s foreign trade since the Japanese surrender clearly shows that most of the country’s imports have been paid for with the help of U.S. government loans and grants; China’s foreign assets — only a tiny fraction of which the Communists currently hold — and exports have covered the rest. Can China sustain itself by exporting its products? Unquestionably not, its only products are hog bristles, tea, silk, tung oil, eggs, tin and tungsten, not much in all, and no necessities apart from the last two. In other words, if one wants to do business with China, one must first extend credit. What businessman would risk this under the current regime? As for governments willing to do so, why don’t they directly subsidize, rather, the branches of their economy that would suffer because of the blockade?

We, the French, would be an insignificant factor in the execution of the blockade; our trade relations with China are minimal, and we could endure the loss of the capital we have already invested there without much pain. The blow will be harder for Great Britain, whose government is hoping to save Hong Kong and its £300 million capital; to this end, it intends to adopt a conciliatory policy towards the communist Chinese government, providing it with what China needs in exchange for certain guarantees for its capital. As long as the Sino-Soviet alliance lasts, these guarantees are unrealistic and will not save British capital when war breaks out. We can also expect stubborn opposition from certain American business circles, shipping companies, oil exporters, etc. We still have a few months to convince them; the question of China’s foreign trade will not arise in any serious way as long as the Communists are busy reducing their opponents entrenched in Formosa.

Let us now conclude this study by formulating a simple and positive plan of action. We must

1- Devote all our intelligence efforts to determining the USSR’s attitude towards Communist China. If it is harsh, we may not need a blockade; our present passive attitude may suffice. Let’s give ourselves 6 months for this.

2- During these six months, seek agreement from Western countries on a possible blockade of China. Naturally, these talks should be held in secret, as there’s no point in giving Communist propaganda a weapon before events themselves reveal the blockade.

3- If this agreement is reached, and if it turns out that the USSR shows a tolerant attitude in its relations with Communist China, apply the blockade, the severity of which may be moderated according to the changing situation.

Salonika, January 26, 1950

Captain D. GALULA, French military

Observer, l’UNSCOB.

citer l'article

US And The China Problem: A Lost Archive Of David Galula, Oct 2024,