The Architecture of Development in the Trump Era: Towards a Geopolitical Pivot in European Solidarity Policy

Alexandre Pointier

Director for Senegal, The Gambia, Cabo Verde and Guinea-Bissau at Agence française de développement (AFD)19/02/2025

The Architecture of Development in the Trump Era: Towards a Geopolitical Pivot in European Solidarity Policy

Alexandre Pointier

Director for Senegal, The Gambia, Cabo Verde and Guinea-Bissau at Agence française de développement (AFD)19/02/2025

Voir tous les articles

Voir tous les articles

The Architecture of Development in the Trump Era: Towards a Geopolitical Pivot in European Solidarity Policy

Dismantling USAID 1 , withdrawing from the Paris Agreement, withdrawing from the WHO 2 , the announcement of possible reduction or suspension of contributions to several UN agencies (UNRWA 3 , UNESCO 4 , UNFPA 5 ), criticism directed at the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund; the early days of President Trump’s second term have been defined by a significant hardening of his policy on aid and development, whether bilateral or multilateral. Going forward, there is only one guiding principle: supporting the economic and security interests of the United States.

As such, Donald Trump is destabilizing a development architecture that was established 80 years ago and is at the heart of the post-World War II project for peace and prosperity. This architecture, which was, however, conceived from the outset by the United States as a project of global power and organization, is struggling to withstand this “hyper-realist” approach (absolute priority of national interests, rejection of multilateralism, Hobbesian vision of international relations), which Trump applies to all aspects of his foreign policy (trade policy, conflict management, etc.).

Today, the policy of international solidarity has no other choice but to reinvent itself.

Between the institutionalized, idealistic approach to the development ecosystem (cooperation and collective reason, commitment to international rules), which has gradually become independent of political powers, and the hyper-realistic approach of maximizing the gains that can be obtained from international power relations, there is a path to be forged that is both win-win and based on mutual respect.

The acceptability of this policy depends on both the taxpayers of the richest countries and the beneficiary countries, who are showing signs of fatigue with regard to “development aid”, not only because it can sometimes come across as ‘overbearing’, but also because it no longer seems capable of responding to the challenges — particularly related to demographics and climate — faced by emerging and developing countries.

Europe can spearhead a re-politicized, realistic, and ambitious solidarity policy by anchoring its international partnerships in the strategic realities and interests of partner countries, as well as its own, in a way that goes beyond simple narrative 6 . This must begin by fully integrating international solidarity policy into European economic, industrial, and foreign policies. A prime example of this renewed approach would be the creation of a Mediterranean-European community of renewables.

From a strategy of stabilization and influence to bureaucratic autonomy

On January 20, 1949, beneath the white dome of the Capitol, Harry Truman gave his inaugural address. Economic and social policy, international policy… everything was fairly conventional, until point 4, which challenged his audience at the time. In fact, he was introducing the concept of development aid when he declared, “We must embark on a bold new program for making the benefits of our scientific advances and industrial progress available for the improvement and growth of underdeveloped areas”. This speech would lead, a year later, to the signing of the Act for International Development.

The decision to support countries that President Truman then called “underdeveloped” — a decision that must be viewed within the context of the beginning of the Cold War and the process of decolonization — was clearly underpinned by a dual objective of stabilizing the world order and, in the recently decolonized countries, exerting influence to counter the Soviet Union. The Marshall Plan, implemented a few years prior to rebuild Europe, served as a model for this approach; by financing infrastructure, education, and agricultural modernization projects, the United States hoped to not only stimulate growth, but also ensure the political loyalty of beneficiary countries.

But how can this challenge be met? How can the growth of developing countries be promoted? How to contribute to the stability of a country? To examine the history of development aid is to revisit almost 75 years of collective beliefs, the relationship with the market economy, and the increasing importance of agencies for carrying out public policy.

Broadly speaking, there are four main periods. In the 1960s and 1970s, the activities of development institutions centered on economic growth — major industrial projects, infrastructure, agriculture – before embracing the principles of the “Washington Consensus” in the 1980s: the opening up of markets, privatisation, and the reduction of public spending. This approach, which was swiftly criticized for its social effects, gave way in the 1990s to a discourse by international donors focused on the fight against poverty, with funding directed towards the education, health, and employment sectors. This period also saw the rise in initiatives promoting entrepreneurship. Noting the failure of certain programs, development institutions made another shift in the early 2000s and began to place greater emphasis on governance and institutions. Investments were then directed towards promoting transparency, accountability, and citizen participation. Today, the focus is on the climate emergency and the financing of mitigation projects (renewable energy, energy efficiency, etc.) and adaptation projects (ecosystem and community resilience).

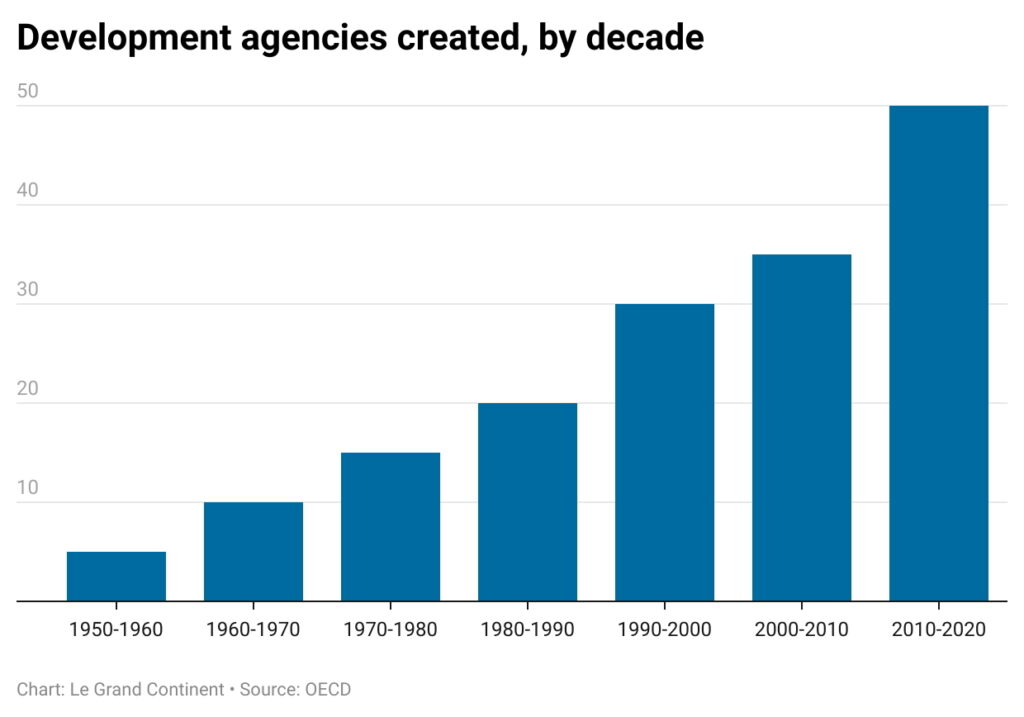

Although priorities have evolved over time, efforts by the various actors have tended to layer on top of each other rather than replace each other. As a result, most donors are now involved in the full range of public policies, whether economic, social, governance, or climate-related. We are also witnessing, through international summits, a proliferation of development agencies, programs, and organizations (regional banks, specialized funds such as the Green Climate Fund, sectoral agencies such as Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, etc. – see graph 1) 7 .

In Senegal, for example, there are more than 70 international organizations, including 34 United Nations agencies, funds, and programs. Hundreds of people claim to be “specialists” in education, health, or entrepreneurship policies, each piloting their own program or initiative, with varying degrees of coordination with the government.

More fundamentally, during the transition from the 1980s to the 1990s, the field of development aid became largely autonomous and depoliticized.

In their book Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics, Martha Finnemore and Michael Barnett very clearly describe how international organizations develop their own dynamics of autonomy and power, shaping a field of action relatively independent of national governments. International agencies behave like bureaucracies that, beyond their initial mandate, acquire their own skills and routines. They develop their own values, their own language and specific objectives, which are at times independent of the immediate political interests of the founding states.

In order to affirm their autonomy in relation to political authorities, international organizations have relied on mechanisms that are well known in the sociology of organizations (professionalization, with experts forming a “transnational elite,” bureaucratic routinization and standardized protocols, which reinforce their decision-making power, etc.) as well as a political context favorable to a depoliticization of development policy (the end of the Cold War, the emergence of global public goods such as health and the climate, New Public Management, etc.).

Finally, these institutions, in addition to seeking to expand their prerogatives, continually aim to increase their financial resources. As a result, international summits — from conferences of the parties (COPs) to United Nations general assemblies —place more importance on new funding announcements than on analyzing the results of past initiatives or evaluating the effectiveness of the actors involved.

An ecosystem that no longer meets the needs of developing and emerging countries

What has been the result of this ecosystem, which is the result of 75 years of cumulative development policies?

Here again, the debate — on the relevance and effectiveness of development aid — is a long-standing one that dates back to the 1960s.

At the microeconomic level, many development projects have directly improved the living conditions of the beneficiary populations. This is the case, for example, in the areas of health, access to drinking water, education, and the agricultural sector. Cash transfers and social safety nets have, for their part, made it possible to reduce poverty in the short term, during times of crisis or great hardship.

At the macroeconomic level, however, it is clear that the development policies implemented by Western countries for the benefit of countries in the Global South have not delivered on all their promises, particularly on the African continent. While extreme poverty worldwide fell from 36% in 1990 to 8.6% in 2018, this rate decreased by only 14 points over the same period in sub-Saharan Africa, standing at 40% in 2018. Furthermore, growth in poor countries has often come with increased inequality: the Gini coefficient there rose from 0.43 in 1990 to 0.49 in 2019.

Critics of aid raise two main arguments. On the one hand, they criticize the dependency it creates, which hinders fiscal reforms and encourages corruption. On the other hand, they point out that countries such as China have managed to develop with little external aid.

The dispute between those who are cynical about development aid and those who are idealistic about it is embodied in the debate between the economists William Easterly and Jeffrey Sachs. In The Elusive Quest for Growth, Easterly argues that development aid can be counterproductive when it comes to creating incentives to encourage innovation, productivity, and local investment. In contrast, Jeffrey Sachs (The End of Poverty) argues for a large influx of aid to break the vicious circle of poverty, which he considers an obstacle to good governance, thereby upending the traditional line of argument.

What should be made of this debate? Econometric studies have struggled to come to a conclusion; no clear correlation between aid and growth has been demonstrated. In the absence of counterfactuals and universal evaluation criteria, the debate is ongoing. However, this uncertainty reveals an essential reality: development depends above all on internal dynamics. Stefan Dercon therefore emphasizes that the key to development lies in a “developmental compromise,” in which the political, intellectual, and economic elites collectively commit to growth 8 . This model would explain the success of countries such as China, Ghana and Rwanda, even though these countries have opted for very different paths to growth (democratic or autocratic regime, emphasis on the public or private sector, etc.).

Consequently, it may be tempting to conclude that, like democracy, development aid, with all its limitations, is the worst system, except for all the others. Yet, as with our Western democracies, the status quo is not an option.

Two undercurrents threaten to destabilize the current equilibrium.

On the one hand, there is the African demographic wave. By 2035, more young people will enter the labor market in Africa each year than in the rest of the world combined. This means 15 million jobs to be found every year. At the same time, the working-age population in Europe is expected to decrease by about one to two million per year.

On the other hand, the climate wave. International relations are reorganizing around the issues of climate and energy transition: fierce competition to develop and dominate clean technologies, the race for access to the resources necessary for green technologies such as lithium, cobalt and rare earths, the redistribution of influences between fossil fuel producing countries and countries in transition, tensions between greenhouse gas emitting regions and regions that absorb these gases, etc. Excluding developing countries from this transition would, at best, make way for strategic competitors or, at worst, entrench inequalities in an essentially post-carbon world (carbon-based energy limited to the South versus greener and more abundant energy in the North; lack of participation of African countries in the rare metal mining value chain, etc.).

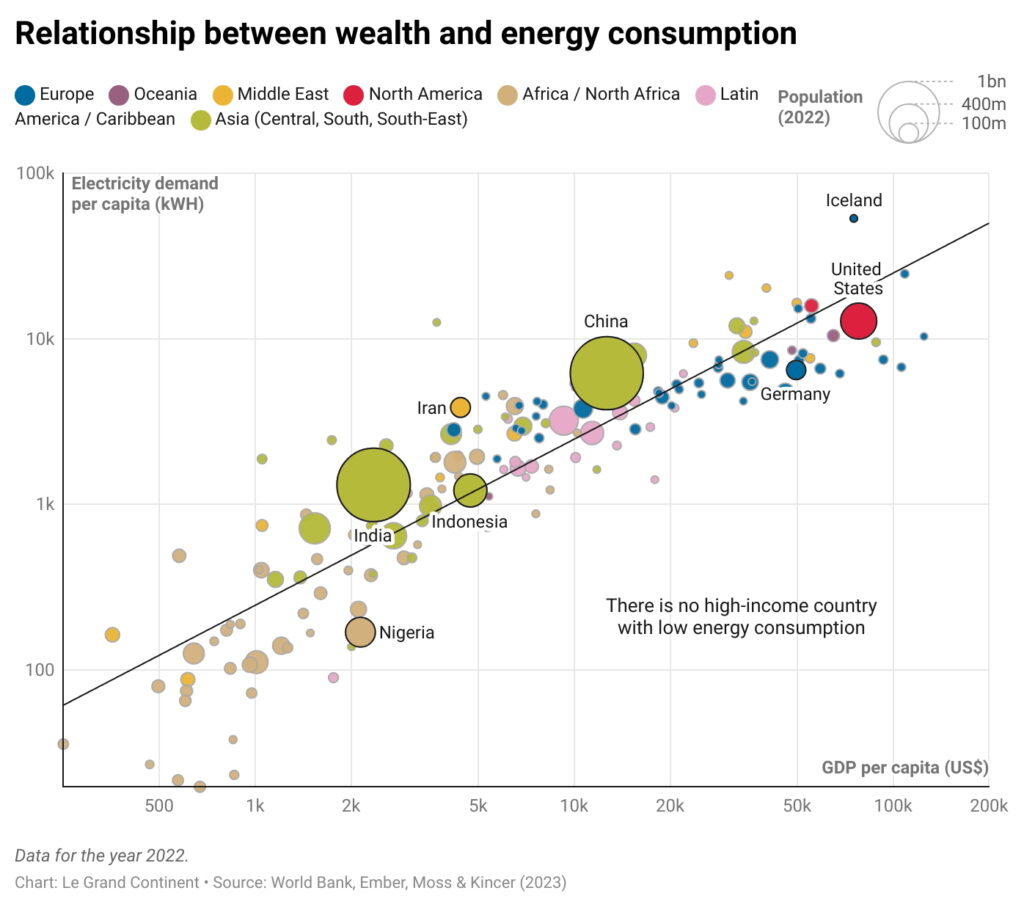

Of course, these two waves are closely connected because there can be no growth and no jobs without energy consumption (see graph 2), and this energy will have to be green in the future 9 . While there is no doubt that we must encourage a kind of sobriety in rich countries, it is inconceivable to ask the poorest countries to develop without energy.

In this context, the lack of significant and visible results for the poorest countries, particularly in Africa, undermines the credibility of current development institutions, with a growing divide between the promises of major international summits and the reality on the ground (which is also, because the results are not zero, the disparity between what Giovanni Orsina calls “hearsay” and the “touched by hand” 10 ). More fundamentally, the failure of the demographic and energy transition processes in these countries would create catastrophic human situations 11 and would inevitably lead to a profound weakening of the conditions for peace.

The international community has recently stepped up its efforts to address the challenge of moving from microeconomic impacts to sustainable macroeconomic transformations, launching several ambitious projects, with sectoral and geographical priorities. This is certainly the right approach. As such, at the 2021 One Planet Summit, the Great Green Wall project — which is supported by the African Union and aims to restore vegetation to the Sahel from east to west — received $14 billion in support from major donors. The same year, at COP26, the international community announced cumulative commitments of 8.6 billion dollars to support South Africa in the closure of its coal-fired power stations and the transition to green energy. But despite the political backing of these large-scale projects, they suffer from well-known dysfunctions: fragmentation of initiatives and lack of cooperation, commitments in principle prior to technical analyses, efforts to mobilize the private sector in countries where the conditions are clearly not in place, inadequate accountability and monitoring systems, etc. 12

The frustration on the part of the southern countries is already palpable and emerging countries are pushing for the creation of a complementary system — some would say an alternative one. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was founded in 2015 at the instigation of China and, more recently, the New Development Bank (NDB) was created by BRICS to reduce their dependence on financial institutions perceived as Western (only emerging countries represented in its governance, loans in local currency rather than dollars, absence of market economy conditionalities). On a bilateral level, Chinese initiatives such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and the Global Development Initiative (GDI) also illustrate the desire to offer an alternative way of supporting the development of partner countries, with long-term planning of cooperation projects linked to the political and strategic challenges of the Chinese side.

The status quo is therefore no longer an option.

Europe must spearhead a repoliticized, realistic, and ambitious policy of solidarity

So, what can be done to ensure that development aid once again becomes a force for peace in the 21st century?

At both the bilateral and multilateral levels, the political dimension – in the noble sense of the term – of the tools of solidarity must be more fully embraced. By accepting a realistic approach of balancing the interests of donors and those of recipient countries, the richest countries will have more incentive to make these instruments effective. And by abandoning the approach of aid or assistance in favour of partnerships of equals, stable and lasting relations between countries can be established.

Europe, in particular, cannot be satisfied with the geopolitical gains of its development policy. The European Union and its member states provided €95 billion in development aid in 2023, or 42% of global aid. But the impacts in terms of influence or the economy, as well as the satisfaction of the beneficiary countries, particularly in Africa, do not seem to be living up to these commitments.

In order to consolidate political and strategic autonomy on the geopolitical chessboard, when up against the United States and China, as well as to counter the idea of a Global South, two levers must be used: the geographical and sectoral prioritization of our resources and the alignment of our public instruments.

Who are our key partners in the coming decades and what mutually beneficial cooperation can we build that will meet the challenges of the 21st century?

We no longer have the luxury of being able to be everywhere. The European Union’s contribution to repairing a highway in Laos or to the electrification of public transportation in Costa Rica is important and commendable, of course, but it is not as vital as supporting the reconstruction of Ukraine or the transitions in the Maghreb and the rest of the African continent. As Tim Marshall reminds us in Prisoners of Geography, even in an interconnected world, individual nations remain “prisoners” of their physical environment. Geography is unyielding.

Accordingly, supporting the demographic, energy, and climate transition in Africa should be a political obsession for Europeans. Failing to do so could have major human and geopolitical consequences.

Beyond the European neighborhood, we must recognize that our destiny is linked to that of the African continent, and we must once again find the level of ambition which prevailed during the Treaty of Paris in 1951 and the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC). If we want to develop a cooperative approach to projects with the African continent, we should begin with the energy sector, by establishing the Mediterranean-European community for renewable energy.

In 2021, the Union imported approximately 56% of its energy needs. In terms of new forms of energy, Europe — along with Korea and Japan — will be the geographical area importing the most hydrogen and by-products by 2050. On the other hand, North Africa is known for offering the lowest solar energy production costs in the world, along with the Middle East. Consequently, there is a major geopolitical challenge in forming a long-term and coordinated alliance with our neighbors in order to build a Mediterranean market for green energy, which will be transported by cable in the form of electrons, by pipeline in the form of hydrogen, or by boat 13 . Morocco is starting to export electricity generated by solar and wind farms to Europe, but we need to go much further in terms of volume and involve as many countries from the Maghreb as possible.

Here again, many declarations of principle and partnerships have been signed on this subject over the decades (for example, the Africa-EU Energy Partnership launched in 2007 at the EU-Africa Summit in Lisbon), but we have never fully aligned our economic policy (European Green Deal and in particular its clean energy component), our industrial policy (support for future-oriented sectors), our foreign policy (securing strategic supplies), and the tools and financing of development policy. We have never concentrated our efforts on just a few countries. We have never set specific objectives based on technical analysis and implemented them according to a methodical plan, jointly developed with our partners.

The Mediterranean-European community of renewables, which would aim to strengthen the economic and energy stability of Maghreb countries and diversify European supply sources, should therefore respond to the threefold challenge of rigorously analyzing the energy constraints of North African countries, establishing a common and lasting political commitment to investment and institutional and public policy reforms, and, finally, ensuring effective management which allows for real coordination between stakeholders. By drawing on recent experiences, and with sufficient political ambition, it is entirely conceivable to produce tangible results in the next ten years 14 .

This is also the type of commitment that is more likely to effectively address the issue of migration than simply increasing the costs of migration through border walls, sanctions, or curtailing the rights of migrants in their destination countries.

This is, of course, just one example. We must be equally ambitious with regard to what we can jointly develop with emerging countries that are not completely aligned with the United States or China, such as India, Brazil, or Indonesia.

Politicizing development policy also means putting pressure on multilateral organizations such as the World Bank and regional development banks to align their projects with European priorities, once these have been clearly defined. We must accept that development policy can be rooted in an approach based on power, albeit within a system where the sum of these different approaches to power can create stability, along with a basic framework of cooperation, to enable responses to shared challenges. Europe, as the main contributor to international organizations, and against a backdrop of US disengagement, must develop a level of influence commensurate with its financial commitments.

European development policy – or international partnership policy – must regain momentum and vision by firmly rooting itself in truly transformative ambition, driven by equitable cooperation with its partners. The global challenges we face – from climate change to demographic developments and the transformation of global value chains – require a radical overhaul of our approaches. This boldness cannot solely be the domain of those who want to turn in on themselves. It can be the driving force behind a model where ambition and responsibility come together to build shared prosperity.

Notes

- The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is the agency of the United States government responsible for economic development and humanitarian aid worldwide.

- World Health Organization.

- The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA).

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- United Nations Fund for Population Activities.

- See in particular the statement made by Ursula von der Leyen in September 2019 before she took office as President of the European Commission: “My Commission will be a geopolitical Commission”.

- For a graph showing the dates that the main concessional multilateral funds were created, see Janeen Madan Keller, Clemence Landers, Nico Martinez and Rosie Eldridge, “Replenishment Traffic Jam Redux: Are Donors Getting into Gear?”, Center for Global Development, October 2024.

- Stefan Dercon, Gambling on Development: Why Some Countries Win and Others Lose, 2022.

- Solar power is expected to become the world’s leading source of electricity generation by 2033. See: “Après le charbon et le pétrole, le monde s’apprête à entrer dans ‘l’ère de l’électricité”, le Grand Continent, October 2024.

- Giovanni Orsina, “Politique, technocratie et mondialisation à l’épreuve des guerres culturelles”, le Grand Continent, October 2023.

- The poorest countries are the most vulnerable to climate change — for example, the latest IPCC report points out that by 2050, extremely hot days exceeding 45°C will become frequent and may last for long periods in the Sahel.

- See in particular Global Cooperation for Development: Current Failures and the Case for Collaboration, Hyuk-Sang Sohn and Rachael Calleja, Center for global development, November 2022.

- Pierre-Etienne Franc, “Energy Europe: From Integration to Power”, le Grand Continent, April 2024.

- See in particular the excellent paper by Katie Auth and Todd Moss, which proposes a similar exercise for the United States: U.S. energy security compacts. A Bipartisan Blueprint to Reinvigorate U.S. Influence Through Energy Investment, Energy for Growth Hub, April 2024.

citer l'article

Alexandre Pointier, The Architecture of Development in the Trump Era: Towards a Geopolitical Pivot in European Solidarity Policy, Feb 2025,