The Geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific: France’s strategy

Marc Abensour

French Ambassador for the Indo-Pacific27/02/2025

The Geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific: France’s strategy

Marc Abensour

French Ambassador for the Indo-Pacific27/02/2025

Voir tous les articles

Voir tous les articles

The Geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific: France’s strategy

Today, more than a dozen countries and international organizations have adopted policy documents on the Indo-Pacific, presented variously as strategies, visions, guidelines and perspectives. The geographical scope of these documents also varies, depending on whether the eastern coasts of Africa and the Pacific coasts of the Americas are included.

However, these documents are unanimous in the following three statements:

- The Indo-Pacific encompasses the centre of gravity of the global economy, contributing more than 35% of global wealth and 70% of growth. The Asian Development Bank forecasts that it could account for more than half of global GDP by 2050. This is also reflected in considerable economic integration, with more than 60% of trade happening at intra-regional level 1 , buoyant middle classes, and significant investment in innovation, particularly in the digital sector, the region being home to half the world’s Internet users.

- It is the theatre of multiple flare-ups of tensions (China Sea, Korean Peninsula, Taiwan Strait, China-India border, Arabian/Persian Gulf) and strategic rivalry between China and the United States, heightened by an insufficient security architecture;

- It is central to our ability to address global challenges, including the defence of common goods (fighting climate change, protecting biodiversity, promoting sustainable management of oceans and epidemiological surveillance).

The relevance of the term Indo-Pacific also stems from the fact that it refers not only to a geographical space, but also, and above all, to a geopolitical construction. This is confirmed in particular by two intrinsically linked dimensions:

- The pre-eminence of the notion of flows, which are central to the process of globalization, stemming from the “maritimization” of the world and the obsolescence of territorial approaches based on regions and sub-regions. If you focus on connectivity between the Indian and Pacific oceans, analysis of international affairs shifts from land to sea (90% of global exports are by ship, 99% of Internet connections via undersea cables, and a large share of energy supplies are delivered by sea);

- China’s growing assertiveness, particularly in the context of the Belt and Road Initiative, Maritime Silk Road and, today, Global Development Initiative, as well as their “China+X” variants dedicated to Central Asia, the Indian Ocean, the Mekong Basin and the South Pacific, which are to be integrated within expanded formats where China intends to play a leading role (BRICS+, Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, etc.). In order to address the challenges rooted in this reconfiguration of strategic balances in favour of China, certain countries, and particularly India, plan to act as counterweights, while others hope to maintain their freedom of action by participating in a network of alternative partnerships and alliances.

Moreover, the Indo-Pacific concept, in line with the primacy of the maritime prism, gives rise to a different status for islands. These are often perceived in terms of vulnerabilities (lack of connectivity, impact of climate change) but are now increasingly important actors given their heightened role when it comes to control of shipping lanes and the blue economy.

The adoption by many international actors of the Indo-Pacific concept is thus essentially true to the initial vision developed by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe of Japan as he addressed India’s Parliament in 2007: he called for a “broader Asia” stretching from the Indian to the Pacific Ocean as “seas of freedom and prosperity, […] open and transparent to all.”

However, it should be underlined that adopting the Indo-Pacific concept, or its acceptance by those who do not oppose it totally, particularly small island States, involves different approaches depending on the actors concerned. This differentiation itself guarantees ownership and effectiveness.

In this respect, the French strategy is singular, being built around the following priorities:

- Resisting bloc approaches and the emergence of a new bipolarization;

- Promoting “sovereignty partnerships”;

- Actively supporting regional multilateralism;

- Making overseas territories actors and beneficiaries of the strategy;

- Playing a leading role within the European Union.

This presentation seeks to analyse the overall logic.

1 — Resisting bloc approaches and the emergence of a new bipolarization

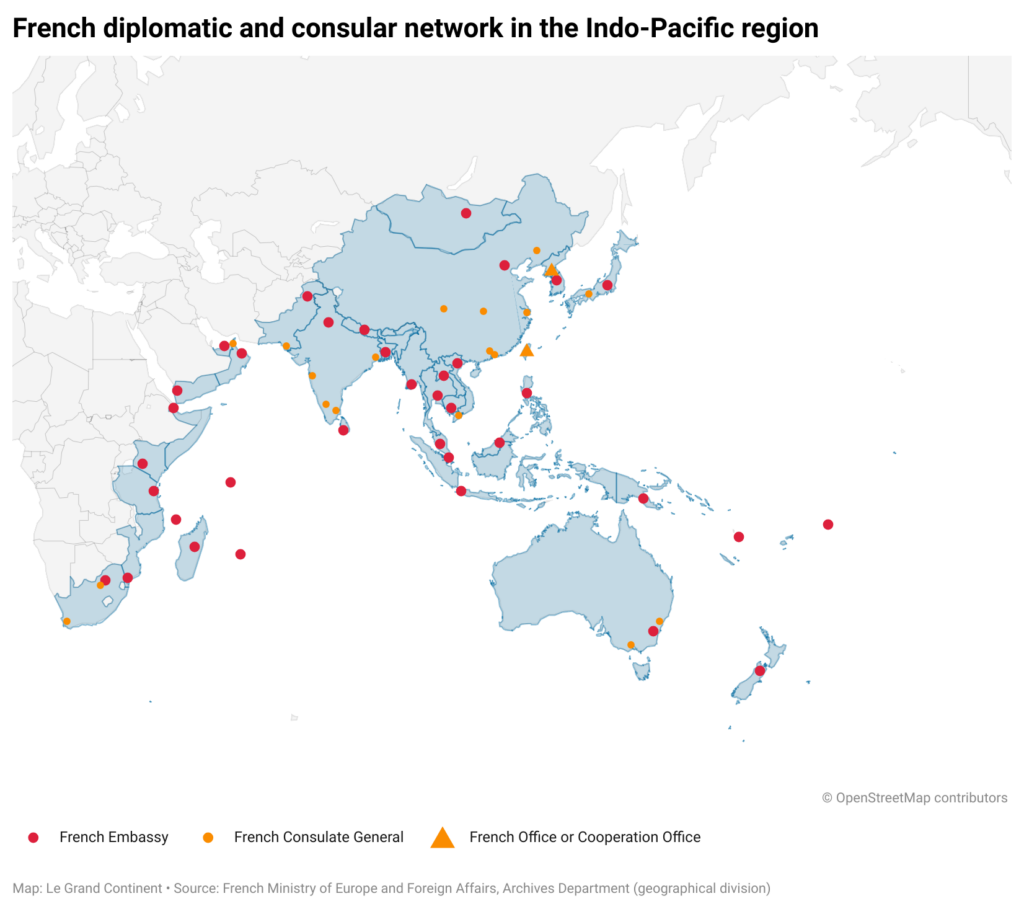

The main principles and objectives of France’s Indo-Pacific strategy, as set out in President Macron’s foundational speeches from 2018 and in policy documents 2 , seeks to maintain a space that is open and inclusive, free of all forms of coercion and governed in accordance with international law and multilateralism. This means constant care to maintain strategic autonomy of analysis and action in the region, as illustrated by the regular and operational deployments of the French National Navy and Air and Space Force. These deployments send strategic signals to our competitors and foster respect for freedom of navigation and overflight, guaranteed access to common spaces and maintained strategic stability in a context of uninhibited power plays. They also enable participation in military exercises to enhance our interoperability with partner countries’ armed forces and conduct surveillance operations, notably with a view to ensuring non-proliferation. In addition to these deployments, France has sovereignty forces (Southern Indian Ocean Zone, New Caledonia, French Polynesia) stationed in the region, as well as forces ensuring a presence (United Arab Emirates, Djibouti), which are being stepped up under the 2024-2030 Military Programming Act.

In light of attempts to build spheres of influence and the priority of seeking strategic alignment, we intend to take an approach addressing the challenge of China’s rise while aiming not to fuel bloc geopolitics, which could heighten China-US competition and risks of escalation and ultimately bring about the self-fulfilling prophesy of inevitable confrontation, as famously expressed by Graham Allison as “Thucidides’ trap” 3 . By focusing on an effective and inclusive multilateral system that can provide tangible, lasting answers, our position seeks to offer our partners an alternative to the Chinese narrative positioning Beijing as a spokesperson for the “Global South” and exploiting the artificial “the West versus the rest” divide. This has involved often unprecedented visits by the French President to several development countries to launch cooperation programmes addressing their key challenges (such as Mongolia in May 2023, Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea in July 2023, Sri Lanka in July 2023 and Bangladesh in September 2023).

In accordance with Europe’s view of China as at the same time a partner, competitor and systemic rival, France maintains demanding dialogue and cooperation areas with the country, particularly on global challenges (climate, non-proliferation, developing countries’ debt) and international crises (Ukraine, Iran, Middle East, North Korea), which are essential subjects to address with it as a permanent member of the UN Security Council. At the same time, France works actively to foster rules of fair competition and the rebalancing of the relationship between China and Europe, based on the “derisking without decoupling” approach.

While seeking not to see the Indo-Pacific as a fundamentally conflictual region, France underlines that its position is in no case one of equidistance between Washington and Beijing. True to its principle of alliance but not alignment, it has many convergences with the United States as a resident Indo-Pacific power as regards regional challenges and responses to them. However, France continues to make clear that our nuances are assets when it comes to building strategic complementarity with the United States. In this spirit, a bilateral France-US dialogue was established in 2024 between the Political Director of the French Foreign Ministry and the US Deputy Secretary of State. This dialogue seeks to bring to fruition tangible cooperation illustrating our synergies in a variety of domains, ranging from maritime security to natural disaster response, the climate and infrastructure projects while leveraging our comparative advantages with respect to the different regional partners.

This French positioning (no confrontational approach to China, no equidistance between Washington and Beijing, no strategic alignment with the United States) is generally well understood and appreciated by the Indo-Pacific countries, the vast majority of which fear having to “choose” between Washington and Beijing. They see diversifying their partnerships as an opportunity to enhance their wriggle-room to best “navigate” in an environment that is increasingly subject to strategic competition between major and regional powers. Indo-Pacific countries have addressed attempts at regional hegemony by developing circumvention and avoidance strategies. Some take part in multiple and competing institutional formats and even partnerships and alliances that could be seen as mutually exclusive (such as the “multi-alignment” strategy that means India can take part in both the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization). Others engage in what could be seen as hedging, highlighting their assets to each competitor as is advantageous with a view to defending their interests and freedom of action. Many of these States, some of which gained independence relatively recently, have traditionally sought to stay out of power rivalries, including those between the USSR and US, and today need to address the fact that China has become their leading economic partner. For some countries that have chosen strategic alignment, an alternative is to maintain a degree of ambiguity as to a possible change of allegiance.

The French strategy therefore has to address this heightened fluidity of international relations, which is embodied by these partnerships of convenience and strategies of multiple interdependencies, while seeking to uphold a lasting framework of shared interests and values.

2 — Promoting “sovereignty partnerships”

The French strategy seeks to address all challenges faced in the Indo-Pacific through a cooperative and multidimensional approach. Above and beyond defence and security, which are a structural component, it also focuses on fighting climate change, protecting biodiversity, and fostering sustainable ocean management, connectivity and health. In each of these fields, our priority is to forge “sovereignty partnerships” with Indo-Pacific countries. These partnerships are conceived as shared goals of reducing dependencies and enhancing resilience through cooperation programmes addressing common challenges. Each partnership is win-win in terms of autonomy, and together they offer a positive agenda in response to the key challenges in the region.

The Agence Française de Développement (AFD) is one of the leading French agencies in the Indo-Pacific, with outstanding amounts totalling €11.2 billion (23% of its global balance sheet), mostly dedicated to climate resilience, biodiversity protection, sustainable ocean management and green finance. It also supports the work of multilateral banks in the region (World Bank, Asian Development Bank and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank). Its remit has been broadened and now includes activities with Pacific islands under regional projects fostering climate change adaptation 4 . The AFD has also expanded its network in the South Pacific by opening offices in Vanuatu, Fiji and Papua New Guinea, and increasing its regional budget five-fold with a view to reaching €200 million in 2027.

Tangible achievements in this context include the Varuna programme for the Indian Ocean. This was financed by the AFD, working with partners including the French Research Institute for Development (IRD) and Agricultural Research Centre for International Development (CIRAD) and with Expertise France as project manager, aiming to protect biodiversity and manage marine protected areas. Another example is the BRIDGES programme for climate resilience and adaptation of socio-ecological systems and marine ecosystems. In Oceania, the KIWA Initiative now covers 19 Pacific island States and territories to fight the impact of climate change using nature-based solutions such as organic farms, agroecology and agroforestry extension and restoration of coral reefs. The launch during COP28 of the country package for forests, nature and climate with Papua New Guinea, which has the world’s third-largest area of primary forest, is also in line with this framework. When it comes to health, the creation of an epidemiological surveillance network for the Indo-Pacific, coordinating existing systems in the Pacific, South-East Asia and the Indian Ocean, strengthens integrated human, animal and environmental health approaches.

All these programmes, which aim to gather a growing number of international donors and are supported for the most part by regional organizations, help to foster an integrated regional or sub-regional approach. They contribute to exchanges of experience and best practices between similar initiatives at Indo-Pacific level and foster partner awareness of the benefits of a pro-active inclusive regional governance approach to address shared challenges. The great number of these programmes, which forge networks of shared interest and solidarity between partners, enables collective action to foster Indo-Pacific countries’ autonomy and freedom of action. They also help preserve and secure the environment of our overseas territories, which face the same challenges as our Indo-Pacific partners.

In support of these programmes, France works to develop key partnerships with certain like-minded Indo-Pacific countries. These include India, with which an India-France Indo-Pacific Roadmap has been adopted, particularly addressing maritime security and state action at sea, the blue economy and ocean governance; an Indo-French Life Sciences Campus for Health has for the region also been created, with the support of Campus France 5 . With Japan, a working group on the Indo-Pacific aims to enhance coordination of projects in third countries addressing priorities such as the climate, the environment and biodiversity, qualify infrastructure and health, with the ambition of building synergies and identifying joint programme opportunities. Our relationship of confidence has been renewed with Australia through an ambitious roadmap 6 , as illustrated by the recent launch of the Franco-Australian Centre for Energy Transition (FACET) 7 , which involves France’s Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA), as well as enhanced coordination of our climate, humanitarian and maritime security action, both in the Pacific but also in South-East Asia and the Indian Ocean. A similar effort has been ongoing with the Republic of Korea since the country adopted its own Indo-Pacific Strategy, which is highly convergent with France’s approach and thus offers new opportunities for cooperation in third countries. A France-Korea Indo-Pacific dialogue 8 has also recently been launched.

Maritime security is a particularly structural priority, given the many challenges in maritime spaces such as piracy, maritime terrorism, arms, narcotics and human trafficking, and illegal, undeclared and unregulated (IUU) fishing. Our ambition here is to help establish a regional maritime security architecture in key zones of interest. The French Navy takes part in European Union operations (Atalanta, Aspides, Agenor) 9 and actively contributes to securing shipping lanes through regular operational deployment of key naval assets (aircraft carrier strike group, nuclear submarines, landing helicopter dock, multi-mission frigates) to defend freedom of navigation and compliance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, including in theatres of tensions such as the Taiwan Strait and the East and South China Seas.

Moreover, maritime safety and security cooperation is regularly undertaken with partner countries, and the Indo-Pacific Strategy is a framework to foster real impetus for a regional maritime security architecture. In this respect, we can draw on existing capabilities within our overseas communities and establish capability-building training programmes based on the French state action at sea model in the region. This goes in particular for the La Réunion-based Regional Operational Surveillance and Rescue Centre (CROSS) for the southern Indian Ocean.

We can also set up training institutes with certain partner countries. In Sri Lanka, for example, we recently launched the Regional Centre for Maritime Studies (RCMS), drawing on the island State’s strategic position in the Indian Ocean, and are working on creating a Security Academy in La Réunion, to supplement its work. The possibility of “shipriding” (placing of foreign enforcement officers on Navy ships for fisheries controls) with certain South Pacific island States, as is already done in the south-west Indian Ocean, is being explored.

We also contribute actively to regional maritime domain awareness mechanisms through regional organizations, with liaison officers present in the various information fusion centres in Madagascar, India, Singapore and Vanuatu. In this respect, France and the EU have particularly advanced systems, as shown by our contributions within EU naval missions and operations and certain European programmes such as Safe Seas Africa. This EU programme seeks to enhance the regional maritime security architecture specifically dedicated to the west Indian Ocean, under the auspices of the Indian Ocean Commission (IOC).

The Indo-Pacific Strategy is thus an effective framework to foster enhanced engagement with coastal and island States on maritime security through greater integration between actors, programmes and relevant regional organizations.

This sovereignty partnerships approach offers an alternative, not to replace other major regional actors, but to enable Indo-Pacific countries to choose their partners in full autonomy, on a project-by-project basis, to ultimately form a network of voluntary interdependences and solidarity.

3 — Actively supporting regional multilateralism

Support for regional multilateralism is another aspect that is key to the French approach for the Indo-Pacific. It is part of the wider framework of our commitment in support of effective multilateralism based on compliance with the rule of law and the Charter of the United Nations. In practice, this means even greater involvement within the regional multilateral organizations that we are a full member of and efforts to do more work in those that we are partners with or simple observers.

In 2020, France became a full member of the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA), which drew up the “Vision 2030 and Beyond” for the Indo-Pacific in 2022. This document includes strong convergences with our own priorities. After having recently decided to strengthen its contributions to the organization in terms of funding and staff, today France is dedicated to promoting a more operational organization alongside its partners, which will ensure tangible progress is made in fields such as the blue economy, the fight against illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, drug trafficking and marine pollution and natural disaster management. IORA’s vision for the Indo-Pacific is also a suitable framework to encourage enhanced commitment of the nine neighbouring African countries of the Indian Ocean within this forum. We also encourage greater coordination of the organization with other regional structures and have actively supported the development of discussions between IORA and the IOC, of which France is a founding member. This helps strengthen interconnection in the region, in particular in the field of maritime security thanks to the support provided to the IOC Maritime Information Fusion Centre (RMIFC) in Madagascar and the Regional Centre for Operational Coordination (RCOC) in Seychelles. France also held the presidency of the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) from 2021 to 2023, and placed a priority focus on environmental security challenges faced by neighbouring countries in the Indian Ocean. It plans to continue its efforts in this framework in support of naval cooperation, in particular with the current presidency held by Thailand.

In the same vein, France became a development partner of ASEAN in 2021. Since then, an action plan was adopted and tangible collaboration projects were set out targeting a certain number of priorities: natural disaster response, global challenges such as healthcare, climate and biodiversity, sustainable development including sustainable farming, the blue economy, the energy transition, heritage, tourism and more. We are now in the implementation phase, with a major role attributed to the Agence Française de Développement (AFD), which has contributed to more than 170 projects in South-East Asia in the past ten years, for a total of more than €4 billion invested. Just recently, this partnership resulted in projects to improve air quality and combat plastic pollution. ASEAN is of special importance for France, particularly because of its commitment to defending international public law and the multilateral system, its cooperative and inclusive approach and convergence between French and European strategies and the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. This programmatic document also announces greater involvement of ASEAN in the Pacific and the Indian Ocean, as illustrated by the recent memorandums of understanding signed by the Association with IORA and the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF). Generally, the role of ASEAN in our strategy is expanding, with a specific focus area supporting the development of connectivity and quality infrastructures. France is also continuing to build closer ties with ASEAN’s defence structures, specifically the ADMM-Plus. It took part as an observer in the Maritime Security and Peacekeeping Operations working groups, which illustrates recognition of its role as a security provider in the area. It continues to work with a view to full membership of this forum.

Our approach also involves strengthening our commitment in the South Pacific, an area of increased competition between major powers, in particular by focusing on the participation of the overseas communities of New Caledonia and French Polynesia in the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), the Pacific Community and the South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP), in which the three communities sit alongside the French State. France expressed its support for the PIF’s 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent 10 and to its Boe Declaration 11 for greater multilateral commitment to tackle threats, particularly the existential challenge of climate resilience, which the communities of the Pacific face. The United Nations Oceans Conference in Nice in June 2025 will be an opportunity for greater consideration of the priorities of the Pacific island States, which are central to France’s solidarity policy (they receive a third of its financial contribution for climate change adaptation and resilience). Following the visit by President Macron to the region in July 2023, we strengthened our contribution to the regional security architecture, as illustrated by the “Pacific Quad” (France, United States, Australia and New Zealand) maritime surveillance operations in the EEZs of the Pacific island States for the Pacific Islands Forum Fisheries Agency, and by our increased involvement in the South Pacific Defence Ministers’ Meeting (SPDMM) 12 and in regional thematic initiatives such as the Western Pacific Naval Symposium.

Our efforts to protect multilateralism must also include the increased number of emerging formats and ad hoc coalitions, particularly at the initiative of the United States, such as the “Quad” in the Indo-Pacific, AUKUS, the US-South-Korea-Japan and US-Japan-Philippines trilaterals and groupings such as the Partnership in the Blue Pacific (PBP). This poses a challenge in terms of coordination with the regional multilateral organizations. We plan to ensure that pragmatism prevails in the face of the rise of “mini-lateralism”. Furthermore, France itself contributed to establishing trilateral formats with India and the United Arab Emirates, and with India and Australia, and does not rule out joining other ad hoc formats in the future (for example as part of the planned India-Middle-East-Europe Economic Corridor/IMEC). However, participation in these groupings of like-minded countries must:

- ensure that the chosen format corresponds to the objectives sought and remains adjustable in line with the principle of inclusivity, to avoid the risk of being seen as an exclusive alliance. Certain formats, which primarily aim for strategic alignment, have been likened to coalitions directed against China;

- prevent the risk of generalized ad hoc coalitions, which could ultimately result in an essentially transactional approach to international relations, to the detriment of our commitment to defending effective multilateralism. It is in this regard that we continue to be particularly vigilant that the ad hoc formats that we take part in provide support to initiatives launched in the framework of regional organizations, if only to avoid the risk of unnecessary duplication. We therefore work in a coordinated manner with India and Australia in the framework of the regional organizations that we are members of, and in particular the Indian Ocean Rim Association.

Regarding the PBP more specifically, of which we are observer members, we are prioritizing the continued work towards the initial objective which was to improve coordination among countries that contribute to natural disaster management in the South Pacific. That is why we are providing financial support for an 8-year period to the programme to build up pre-positioned emergency reserves in the island States (Pacific Humanitarian Warehousing Program), which is also included among the PBP’s priorities, in addition to our contribution to the trilateral partnership with Australia and New Zealand (FRANZ) on emergency assistance in the event of natural disasters.

4 — Involving the overseas territories in the strategy and ensuring they benefit from it

The uniqueness of the French strategy resides in the fact that France is a resident nation of the Indo-Pacific with its overseas departments and communities, which give our approach legitimacy. If we add expatriated French citizens to our 1.8 million overseas compatriots, we have almost two million French citizens living in the area. Our territories, to which more than 90% of our EEZ (the world’s second-largest, with 10.2 million km²) is attached, are therefore key players in the implementation of the strategy. The competences that are found there (State operators such as the AFD and IRD, research institutes, universities etc.) make them valuable platforms of expertise to develop cooperation programmes with partner countries of the Indo-Pacific, in particular in the fields of climate resilience, biodiversity protection, clean energy growth and the fight against transnational threats.

At the same time, the strategy also aims to serve the interests of our overseas communities by prioritizing their regional integration and economic diversification. The French government is working to achieve greater involvement of the overseas territories in drawing up and implementing the Indo-Pacific Strategy, while ensuring France’s foreign policy is consistent. Each of the territories have different competences to do so. As an example, New Caledonia and La Réunion have a network of delegates, which are incorporated under specific terms, within French embassies in their respective regions – we will soon operate in the same way with Mayotte. Our embassies, with the support of the ambassador for cooperation in the Indian Ocean and the ambassador for cooperation in the South Pacific, work in their respective areas to mobilize the economic actors of their countries of residence to encourage trade and investment in support of the overseas territories. It was in line with this desire to involve the overseas territories in France’s foreign policy that President Macron was accompanied by the presidents of the local governments of New Caledonia and French Polynesia during his trips to Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea in July 2023. As a sign of the overseas territories’ contribution to reflection on the Indo-Pacific, the Assembly of French Polynesia set up an information mission on the impact of the French strategy on the communities of the Pacific.

This effort to work together with the local elected leaders must continue with a view to increasing discussions on the geopolitical challenges, enabling the overseas communities to be more involved in the regional organizations, particularly by aiming for senior positions and jointly building the initiatives included in the Indo-Pacific Strategy. It is with this in mind that today we are envisaging the creation of an Indian Ocean Security Academy, based in La Réunion, to foster the integration of the territory and fulfil regional training needs to address common challenges in maritime safety and security, transnational threats and natural disasters. At the same time, a process has begun for the development of a similar security academy in the Pacific, based in New Caledonia, which would offer practical training and exchanges of experience for island States.

The current crisis in New Caledonia is certainly a major challenge. In compliance with the Nouméa Accord and Matignon Agreements, and the right to self-determination, our priority is to put a definitive end to the violence, prioritize dialogue between communities in defining the new status of the territory and reviving economic activity. In this context, we are prioritizing a position of openness, of continuity of discussion and transparency towards the PIF, and we hosted an information mission of high-level representatives of the Forum in October 2024 in New Caledonia, in close coordination with the local government. At the same time, our commitment and our cooperation actions at regional level are being intensified.

5 — Being a driving force within the European Union

France has, from the outset, advocated for an ambitious European Union strategy in the Indo-Pacific. We have done so with the support of other Member States, specifically Germany and the Netherlands, who published their own national guidelines for the Indo-Pacific in September 2020. The adoption by the EU of a strategy for cooperation in the Indo-Pacific in September 2021 was therefore major progress, evidence of the realization made as to the importance of the Indo-Pacific challenges and the need to collectively defend the major interests of the EU in the region. The EU plays an important role in the Indo-Pacific, especially as its primary investor and supplier of official development assistance, and as a leading trade partner (trade between the EU and the countries of the Indo-Pacific represents 70% of global trade). Now the EU needs to be more involved and more visible as a partner in terms of connectivity, security provider and reference actor for the green transition.

In the analysis of issues and the definition of priorities, the French and European strategies are aligned and are mutually beneficial. The European strategy is an extension of the French strategy, because the EU offers the appropriate dimensions to respond to the challenges of the area (connectivity, development, trade and investment) and allows us to defend our values to a greater extent, particularly multilateralism and the rule of law.

In practice, this begins with solid bilateral partnerships between the EU and the countries of the Indo-Pacific, in particular Japan, India, ASEAN members, Australia and South Korea. The implementation of the EU cooperation strategy in the Indo-Pacific depends greatly on the strengthening of these partnerships, the development of trade agreements (signed with New Zealand in 2022 during the French Presidency of the European Union, currently being negotiated with Australia, India, Indonesia and the Philippines), the signing of new green alliances or new partnerships in the field of digital connectivity.

The EU is also equipped with tools and financial instruments to implement its strategy, and these can be fully mobilized under the Team Europe Initiatives, which bring together Member States and institutions in a coordinated effort. This is the case with the Global Gateway programme, which covers five priority fields (digital technology, climate and energy, transport, health, and education and research) with the aim of mobilizing up to €300 billion worldwide across the 2021-2027 period (half of the Global Gateway financing must come from the Member States) and with an expected leverage effect on the private sector. Based on the principles of good governance and ecological ambitions, Global Gateway aims to offer an alternative to partners facing risks of dependency, in particular in the framework of the Chinese “Belt and Road” initiative. A €10-billion investment package for South East Asia was adopted in 2022.

Furthermore, the EU contributes to strengthening maritime security, which addresses an urgent priority considering the Houthi activities in the Red Sea, the growing aggressiveness of China in the South China Sea and the tensions in the Taiwan Strait. In practice this results in the expansion of the “coordinated maritime presence” in the western Indian Ocean, a highly flexible system that combines the roll-out of capabilities, training and joint exercises, and which is open to all partners in the region. It successfully promotes its Critical Maritime Routes Indo-Pacific (CRIMARIO) II programme in the field of maritime situation awareness through its IORIS information-sharing system, increasingly used by navies and coastguards in partners countries, including in the South Pacific. Through the Global Ports Safety programme, it improves port security in the region by offering training on risk management linked to new fuels to decarbonize the maritime industry. Generally, the EU strives to take action in security issues as a “smart enabler”, as shown by its Enhancing Security Cooperation in and with Asia (ESIWA) programme, which has been renewed, with the aim of strengthening operational cooperation and capacity-building in the fight against terrorism and hybrid threats, cyber security, maritime safety and security and crisis management.

France continues to play a driving role in support of the European agenda for the Indo-Pacific. It did so during its presidency of the Council of the European Union in the first half of 2022 by taking the initiative to organize the EU Ministerial Forum for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, bringing together the 27 Member States, some thirty States from the Indo-Pacific region, and representatives of Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean regional organizations. This format has already met three times, the last being in February 2024 in Brussels, with the Forum taking place alongside the EU-ASEAN Foreign Ministers Meeting. It aims to translate the major pillars of the European strategy (security and defence, global challenges and connectivity) into operational terms, with the objective of building operational cooperation programmes pragmatically and which are designed to last. As such, it was deemed preferable by a majority of participants to maintain an original format, without China or the United States, with whom we have separate dialogue channels, in order to preserve an independent space for dialogue and cooperation among Europeans and their Indo-Pacific partners. This format in turn embodies the uniqueness of the French and European approach, which seeks to move away from the inherent bipolarity of the strategic rivalry between China and the United States. The permanent nature of the Forum also helps to ensure that complementarity across security aspects between the EU and NATO are taken into account, as NATO has also developed partnerships with States in the Indo-Pacific region.

Lastly, in Brussels, France continues to advocate for Europe’s geographical integration in this space to be fully taken into account, in the framework of the EU’s Indo-Pacific Strategy, through some of its extremely outermost regions and overseas countries and territories, which are destined to become useful support bases and outposts of European presence.

*

To conclude, continuing to implement the French strategy for the Indo-Pacific must also incorporate the following issues:

- As it is linked, through its genealogy, to the missions of the French Navy for the protection of the sovereignty of overseas France and the defence of freedom of navigation, today the Indo-Pacific Strategy maintains a structuring security and defence component, which is designed to tackle an increasingly difficult strategic environment. Its trajectory is also a sign of developments that now involve including the security-defence nexus in a multidimensional approach that creates synergy across a variety of actors and operators. It is in this regard that defence has an increasingly important part to play in matters of environmental security and natural disaster response.

- Today, our approach combines priority partnerships with certain regional powers (India, Japan, Australia, even South Korea) and a heightened focus on countries that are especially affected by geopolitical rivalries and dependency risks, as proven by our initiatives that target certain island States (Sri Lanka, Papua New Guinea, and Vanuatu for example). Similarly, there is a specific effort underway with neighbouring countries and islands of the south-west Indian Ocean, an area which covers major strategic challenges with the redirection of maritime traffic towards the Mozambique Channel, the resurgence of piracy and the increase in drug trafficking, as well as the increasing influence in the area of our competitors.

- The action by other EU Member States in the Indo-Pacific continues and has even intensified following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, where previously there had been questions as to attempts at relative disengagement. This could be explained by the defence of multilateralism and respect for the principles of the Charter of the United Nations, but there is also an increased awareness of the risks of dependency, particularly economic dependency, and the importance of a variety of partners, especially if we are to strengthen the resilience of value chains.

- Ownership of the strategy by the private sector continues to be an important focus area. Certain major corporations hesitate to enter into this framework which they sometimes liken to a policy of “containment” of China. Ownership therefore happens gradually. A segmented market approach can then be avoided, while the geopolitical factor can be better incorporated in reconfigurating value chains. This is the case for industries linked to connectivity (maritime transport, submarine cables), which are aware of the importance of getting involved in sovereignty partnerships, particularly through the European Global Gateway programme.

It is therefore with regard to all of these challenges that all public and private actors are increasingly taking ownership of the Indo-Pacific strategy, as they see it as a framework that drives diversification in partnerships, increased independent capacity for action and tangible initiatives that support an open and inclusive space, founded on the rule of law and effective multilateralism.

Notes

- See ASEAN Economic Community, Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF).

- France’s Indo-Pacific Strategy (2022), France’s Defence Strategy in the Indo-Pacific (2020).

- The essay in which Graham Allison put forward his theory was published in 2015 (“The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?”, The Atlantic, 24 September 2015); see also Destined For War: Can America and China Escape Thucydides’s Trap?, Boston, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017 and his front-of-the-book piece “The Thucydides Trap”, Foreign Policy, 9 June 2017.

- Pacific Ocean – 2019-2023 Regional Strategy | AFD – Agence Française de Développement.

- Campus franco-indien dans le domaine des sciences de la vie pour la santé.

- https://au.ambafrance.org/IMG/pdf/australia-france_roadmap_04-12-2023.pdf?14726/590fe78bf33462a4bbbaa3476e108988317c523e.

- About us | FACET Franco-Australian Centre for Energy Transition, energy transition.

- Lancement du premier Dialogue Indopacifique entre la France et la Corée du Sud.

- – Atalanta: Navy surveillance operation in the Indian Ocean to ensure maritime security and fight piracy and illegal trafficking.

– Aspides: military operation by the European Union to address Houthi attacks on international shipping in the Red Sea.

– Agenor: the military aspect of the European Maritime Awareness in the Strait of Hormuz mission, which aims to ease tensions and protect European economic interests by guaranteeing freedom of movement in the Arab/Persian Gulf and Strait of Hormuz.

- Stratégie 2050 pour le Continent Bleu du Pacifique.

- Action Plan to Implement the Boe Declaration on Regional Security.

- South Pacific Defence Ministers’ Meeting: meeting of the Ministers of Defence of the seven South Pacific States with armed forces (Australia, Chile, Fiji, France, New Zealand, Papua New Guinea and Tonga). The United States, Japan and the United Kingdom participate as observers.

citer l'article

Marc Abensour, The Geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific: France’s strategy, Feb 2025,