A Mad President Breaks the Atlantic Alliance—A Forgotten History

Patrick Weil

Historian02/03/2025

02/03/2025

Voir tous les articles

Voir tous les articles

A Mad President Breaks the Atlantic Alliance—A Forgotten History

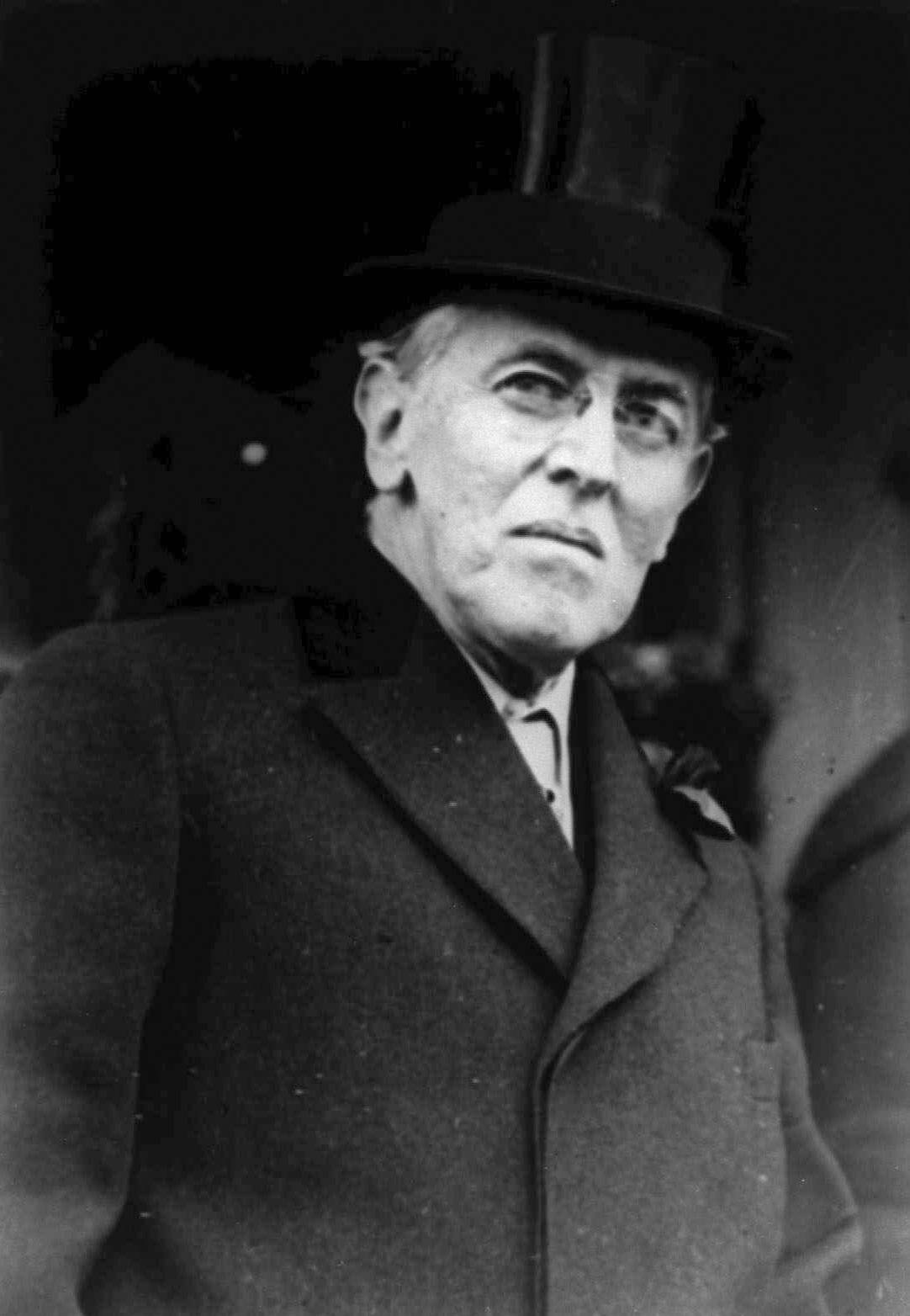

On June 28, 1919, at the same moment as the Treaty of Versailles was being signed, Woodrow Wilson, David Lloyd George, and Georges Clemenceau signed an often overlooked trilateral treaty: The Treaty of Guarantees. The United States and the United Kingdom pledged to immediately intervene militarily alongside France in the event of German aggression. This initial Atlantic alliance was the realization of France’s strategic ambitions, which, with the death of the Franco-Russian alliance following the October 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, left it searching for alternatives. For Clemenceau, this would guarantee peace for both Europe and France. The failure of the United States to ratify the Treaty of Versailles in March 1920, on President Wilson’s orders, made the Treaty of Guarantees null and void. Its demise had an immediate and devastating impact on the disorder that led to the Second World War and on France’s conception of its relationship with the Atlantic Alliance.

Far too often overlooked and forgotten, this is its history.

The Guarantee Pact: the origins of the first transatlantic alliance

On December 14, 1918, a month after the signing of the November 11 Armistice, the President of the United States arrived in Paris where he would stay for six months in order to personally negotiate peace treaties with the defeated powers. His priority was the creation of the League of Nations (LN). As soon as the League’s pact had been negotiated and approved on February 19, 1919, Wilson briefly went back to Washington in order to present it to senators and the American people. On March 14, 1919, he returned to Paris where British Prime Minister David Lloyd George immediately visited him for an urgent reason; he had just submitted to the British cabinet the proposal that the United States and the United Kingdom offer France a special guarantee in case of German aggression. Later that same afternoon, Wilson and Lloyd George met with Georges Clemenceau at the Hôtel Crillon — the headquarters of the American delegation to negotiate the peace treaty — to officially propose a military alliance with their two countries and France which would be called the Treaty of Guarantees. This special treaty guaranteed that, in the event of German aggression, both Great Britain and the United States would immediately join forces alongside France without waiting for LN deliberations.

Wilson saw a number of advantages in this. At the beginning of January 1919, he had included a clause in the LN’s pact which stipulated that each member state would commit to preserving the territorial integrity of the other member states in case of external aggression. Clemenceau wanted an even more powerful LN which would include its own international police, maritime, and land forces, however Wilson opposed it. France, which could no longer count on its former alliance with Russia — which had become Bolshevik — accepted relying on members of the LN to guarantee its security. During Wilson’s trip to Washington, however, the Republicans strongly rejected the automatic solidarity clause included in the pact. In order to ensure the Senate would ratify it, Wilson agreed to its removal. The Council of the League of Nations — made up of nine members, including five permanent members: the United States, France, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom — would unanimously decide on a case by case basis the sanctions to apply in instances of aggression, which meant that the United States, along with each of the council’s member states, had guaranteed veto power.

France lost the guarantee which was contained in the automatic solidarity clause. But it ensured, with the United States and the United Kingdom’s offer, their direct solidarity in the event of German aggression. In exchange, Wilson would ask that France support his amended League of Nations project and abandon its idea of a buffer state on the left bank of the Rhine.

For France, the formation of a trilateral alliance — the Atlantic alliance it had hoped so much for — this was more than enough.

Following the Armistice, as Paris was preparing to host the peace conference, Louis Aubert — a diplomat and close collaborator of André Tardieu, Clemenceau’s right hand man at the conference, with whom he had directed France’s High Commission to the United States between 1917 and 1918 1 — suggested a strategy: putting in place a new alliance which would replace the Franco-Russian alliance. This would be a Franco-American — in a way an Atlantic alliance “given the importance for France of the United States entering world affairs two generations earlier than it would have done if the war had not broken out”. In his note/letter to Clemenceau — who read and annotated it — Aubert bet on “the possibility of gradually bringing the United States around to the idea of an alliance under the cover of the League of Nations” 2 .

And so, this offer arrived without France even needing to ask for it.

Officially, Clemenceau, supporting General Foch — who saw France’s security in controlling the Rhine — had called for the creation of a German state on the river’s left bank, or its permanent occupation. On the eve of Wilson’s return to Paris, Tardieu negotiated with Colonel House, Wilson’s diplomatic advisor, the creation of a temporary republic on the left bank of the Rhine. Returning to Paris, Wilson disowned his collaborator. Standing in agreement with Lloyd George, he refused to accept an upside-down Alsace-Lorraine which could cause a permanent desire for revenge in Germany and among the Germans. It was a hard and definitive ‘no’, which the two allies made up for by offering Clemenceau this Treaty of Guarantees. Later, many wrote that Clemenceau had to concede to Wilson in foregoing the buffer state or the permanent occupation of the Rhine’s left bank. Clemenceau, for his part, indicated that the results of the treaty were what he had sought since the beginning, which was an alliance with the United States and the British empire.

As soon as he had received the offer from Lloyd George and Wilson on March 14, 1919, Clemenceau shared the information with Tardieu and Louis Loucheur, his Minister of Armaments. After reminding them of the United States’ and England’s firm opposition to a permanent occupation of the Rhine’s left bank, he told them, “We must therefore choose: either France alone on the left bank of the Rhine, or France restored to the borders of 1814, that is to say, with Alsace-Lorraine and part, if not all, of the Saar, and America and England allied with us” 3 . Clemenceau believed that it was a risk worth taking because, if the Treaty of Guarantees was ratified, it “was sufficient to prevent war” 4 . Germany would never again attack France if American and British military solidarity would immediately intervene. This was NATO before the term existed, protecting France not from Soviet Russia, but from Germany.

However, given the geographical distance between England — and to an even greater degree the United States — and France, there would, in the event of a German attack, always be a period when the Republic would have to defend itself on its own. For this reason, Clemenceau demanded and obtained, after long and laborious negotiations, a temporary occupation of the Rhine’s left bank — for a period of fifteen years — after which the withdrawal from the Rhineland could be further postponed if the guarantees against German aggression were insufficient; for example if the Treaty of Guarantees was not ratified by the American Senate.

On the whole, each of the three main allies saw its priorities met: the British Empire gained most of the German colonies and the heavy reparations imposed on Germany, which could be partly paid back to its dominions — Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada; the United States gained the League of Nations, which placed them at the core of the world diplomacy; and finally France gained the return of Alsace-Lorraine, a portion of reparations and, thanks to this Atlantic alliance, military security.

For Louis Aubert, the consequences were clear: “an alliance between Great Powers, even one strictly limited in principle to a defensive purpose, always tends to give rise to a political group that develops the habit of consulting each other on all major issues. Little by little, the Entente was formed around the Franco-Russian defensive alliance.” The new Franco-Anglo-American entente would dominate international politics for half a century. Why? Because the US and the British Empire were the two greatest world powers, with whom France had “a direct interest in both hemispheres” throughout the world. They were the two greatest maritime and liberal powers, “consequently hostile to any domination of the continent by Germany. It is their support that will best enable France and its Slavic friends to resist Pan-Germanism, whether it takes on a socialist or military guise.”

America’s involvement in European affairs would, in his view, only be beneficial. He continues: “Its enormous and guileless strength can renew our continent’s affairs,and as there is no country with which France, given its democratic nature, has more affinities, this renewal can only be favorable to us. Backed by the Anglo-American alliance, France is now free to once again set its own course in Europe and the world and, for the first time in fifty years, to start being itself again.” 5

The French and British parliaments ratified both treaties, Versailles and the Guarantee, the latter being unanimously approved by the House of Commons.

All that remained was the American Senate, which came under Republican control in the November 1918 elections. When Woodrow Wilson presented the Treaty of Versailles to the Senate on July 10, 1919, he knew what was at stake. He needed support from two-thirds of the upper house to ratify the Treaty and thereby secure his legacy to humanity: the League of Nations.

Wilson had the opportunity to win over a Republican majority that was afraid of seeing the United States tied down by international commitments. In order to ease their fears, he could tell his opponents that he had taken into account their desire to limit the guarantees of military assistance to the wartime allies, France and England. This was the wish of former president Theodore Roosevelt, who had just passed away in January 1919, and it was still the wish of the majority of the Republican leaders (Cabot Lodge, Elihu Root and Philander Knox) and even of a majority of the 16 “irreconcilable” senators, die-hard opponents of the League of Nations; they advocated maintaining the current alliance against Germany in peacetime 6 and saw France and England as a necessary bulwark against potential German aggression. After all, if Germany were to emerge victorious, the United States, faced with a belligerent empire controlling the Atlantic shores of Europe, would have to make colossal investments in military equipment to ensure the security of its own continent. They were therefore ready to join an “alliance of allies” and to approve the special treaty with France to ensure its security 7 . What they did not want was an organization that would permanently draw the United States into interventions everywhere in the world.

Wilson also considered the guarantee pact to be the only firm commitment from the United States: “We will not wait for the concerted action of other countries under the League of Nations, but will come immediately to France’s assistance if Germany makes any unprovoked movement of military aggression against her.” 8 Wilson could also tell the Republicans that he had incorporated their other demands: the guarantee of the Monroe Doctrine and the right of withdrawal from the League of Nations.

Wilson’s ‘madness’ and Clemenceau’s solitude

But Wilson did not speak those words to the senators. Instead, he entrenched himself in religious vocabulary. The old system of international relations was satanic and needed to be defeated: “The monster that has resorted to arms must be put in chains that could not be broken,” he averred. And in bringing to the world a new and better covenant, he was the vessel of divine will: “The stage is set, the destiny is disclosed. It has come about by no plan of our conceiving, but by the hand of God who has led us into this way. We cannot turn back.” 9 He also chose to postpone presentation of the Treaty of Guarantees with France — it took repeated pressure from Republican senators for Wilson to submit it to them on July 29, 1919.

Until March 19, 1920, Wilson opposed the interpretive reservations put forward by the Republicans. The most important one made any American military intervention to maintain the territorial integrity of another state — deriving from Article X of the Covenant of the League of Nations — subject to the approval of Congress, which is still provided for in the American constitution. The French and British allies made it known that these reservations were perfectly acceptable to them. Even with these reservations, the Senate still had a majority in favor of ratifying the Treaty. However, at the end of February 1920, Wilson asked Democratic senators to reject the treaty.”The “Lodge reservation”, seeking “to deprive the League of Nations of the virility of Article X”, was, according to Wilson, an attack on the very heart of the Treaty. For him, either America entered into the Treaty without fear of taking on the moral obligation of global leadership that it now had, or it would withdraw from the community of powers. One of the irreconcilable senators noted that, by refusing to compromise, “The President strangled his own child.” The press judged that Wilson himself had become “irreconcilable”. He had also acknowledged that any potential entry into war by the United States would require the approval of Congress, but if he was required to have it in writing — that is, to have the name of the Republican Senate majority leader Cabot Lodge appear next to his own in the document of ratification — he could not accept it. On March 19, 1920, at the final vote, the Treaty, including Lodge’s reservations, seemed to have rallied enough Democratic senators to achieve a two-thirds majority needed for ratification. It took all the efforts of two members of the cabinet sent by Wilson to the Capitol, to prevent only twenty- one Democrats from disobeying the president. A total of forty- nine senators voted in favor and thirty- five against, seven votes short of the two- thirds majority.

In his Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1945), historian Thomas A. Bailey summed up Wilson as “the supreme paradox”: “he who had forced the Allies to write the League into the Treaty, unwrote it. He who had done more than any other man to make the covenant, unmade it—at least so far as America was concerned. And by his action, he contributed powerfully to the ultimate undoing of the League, and with it the high hopes of himself and mankind for an organization to prevent World War II.” 10

The cause of Wilson’s fatal obstinance in the fall of 1919 will always remain a matter of speculation.

There were those who thought that the stroke he suffered on October 2, 1919, had played a major role. But this view was in the minority. Many attributed Wilson’s behavior to psychological factors. This was the case with Churchill, Keynes, Cabot Lodge, and Lansing, Wilson’s Secretary of State. The work of Freud and the American diplomat William Bullitt had reinforced this approach 11 .

In the weeks that followed, England withdrew from the guarantee treaty. On the eve of its signing, Lloyd George had slipped in a word without Clemenceau noticing: the guarantee treaty would enter into force on the British side “only” if the United States ratified it 12 . When the U.S. failed to do so, Great Britain in turn declined any obligation of solidarity with France.

After the US Senate vote, the whole world understood that although the Treaty of Versailles would formally enter into force, without US participation it provided little guarantee of an enduring peace. In Paris, the press emphasized Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau’s failed bet on a transatlantic alliance with the United States. French General Ferdinand Foch, the supreme allied commander who led the Allies to victory, predicted a new war would eventually break out and told a friend, “If we are not careful, our army will be significantly inferior in 1940 than it was in 1914.” 13

Clemenceau, however, retired since his defeat in the presidential election of January 1920, did not renounce the Atlantic Alliance.

Against the advice of the American and French governments, he decided to make a trip to the United States at the end of 1922. Wherever he stopped, from his arrival in New York to his subsequent visits to Boston, Chicago, Baltimore, Saint Louis and Washington, Clemenceau spoke to packed halls and stadiums. Before each audience, he addressed the issue of relations between France and Germany. He further developed this idea that “after a terrible war that had almost destroyed both countries, the smaller of the two victorious countries is in danger of having to fight again with the larger one, which may want to erase the humiliation of defeat”.

Clemenceau conveyed France’s situation to thousands of Americans who came to attend his meetings: “Imagine the United States bled of 6 million of its workers and industrial regions by a powerful enemy. That this enemy was pushed back to the other side of the Rio Grande or Canada with the help of England and France. But afterwards they left and told you to fend for yourselves, to seek payment for the cost of the war from the enemy, and with that money to repay France and England for the loans made during the war to keep the soldiers on the battlefields and feed the people to prevent famine.” 14 He continually pointed out that world peace depended on restoring cordial relations between France, England and America 15 . But he also sensed that the American government was not ready to do so.

So, when Colonel House one day proposed to Clemenceau that he initiate a meeting with Hindenburg — House knew how much the latter respected the “Tiger”, and vice versa — Clemenceau did not say no 16 . Georges-Henri Soutou showed how Clemenceau had, in the spring of 1919 through two secret envoys in Berlin, resumed contact with the Germans. He was aware that an economically viable Germany was necessary for the reconstruction of France and also wanted to prepare France for the possible absence of the Americans. Through his contacts, Émile Haguenin and René Massigli, Clemenceau learned that for Germany, territorial losses were less important than damage to its economic potential. And that Silesia, which produced 44 million tons of coal, was more important to it than the Saar, with its production of 13 million tons 17 . That is why, when Lloyd George proposed putting the status of Silesia to a referendum rather than automatically assigning it to the new Poland, as was provided for in the initial draft treaty submitted to the Germans, Clemenceau supported him. Again, in November 1922, anticipating that his American trip might have failed, he had not said no to a meeting with Hindenburg.

But Poincaré’s decision to invade the Ruhr in January 1923 made this plan impossible. Clemenceau judged it severely and it was a failure. This put France in a weak position. So when in 1924 House contacted Clemenceau again to argue that “the suitable psychological moment was approaching to undertake his German adventure,” Clemenceau did not reply. A meeting with Hindenburg was no longer in the cards 18 .

Lasting damage

In France, the United States’ failure to ratify the Treaty of Guarantees continued to cause lasting damage and to draw public attention. Foch had not recovered from Clemenceau’s acceptance of an Atlantic alliance: the “decisive hour” 19 in the long process of the allies finalizing the peace treaties, the moment when Clemenceau dropped the demand for a long-term occupation of the Rhine’s left bank or the creation of an independent state of Greater Germany on this left bank in exchange for illusory guarantees: “nothing remained, therefore, of the promises that had been made to us and which we had recklessly been content with. All that remained was our abandonment.” 20

Foch’s condemnation was published in 1929 after the Marshal’s death and forced Clemenceau to emerge from his seclusion — since 1918, he had only written a preface to Tardieu’s book, La Paix, in 1924. “The Guarantee Pact brought us nothing less than the supreme sanction of the Peace Treaty” 21 , he replied in a work that also appeared after his death. With the English and American allies, it was a question of nothing less than continuing in peace the policy that had brought them to the battlefield;” the guarantee pact ‘was enough to exclude war,’ as the British Foreign Secretary Lord Curzon 22 acknowledged during the British Parliament’s debate on ratification. Its rejection by the United States was an “indirect invitation” to Germany to seek revenge and came as a “cruel surprise” to Clemenceau. It was followed by the United States’ desire to make France — which had served as a bulwark in the war — and all the Western democracies pay for financial commitments that France would be unable to meet. Vilified by the entire French political class, betrayed by Lloyd George and abandoned by the Americans, Clemenceau nevertheless stayed the course: “the international security offered to France, which had accepted it, could not be realized due to the failure of a few weak minds to understand” 23 . His certainty that even without a treaty, England — as well as the United States — would still be an ally in the event of German aggression proved to be correct. In the face of Germany, and later Soviet Russia, the Atlantic alliance was in the shared interest and values of the Anglo-Franco-American powers.

But the painful experience of the abandonment of the Atlantic Alliance by a US President who had committed to it was not forgotten by the leaders of France. Before facing Franklin D. Roosevelt, De Gaulle had observed that between 1918 and 1920, France promoted, achieved, and then saw the first Atlantic alliance fail, to its detriment. This was not forgotten.

Notes

- Cf. Peter Jackson, La conception transatlantique de sécurité du gouvernement Clemenceau à la Conférence de Paix de Paris, 1919, Histoire, Économie et Société, December 2019, Vol. 38, No. 4, VARIA (December 2019), pp. 65-87.

- Private note from Louis Aubert, French opinion and President Wilson, notes by Georges Clemenceau, Archives du Service Historique de la Défense, GR6 N137.

- Louis Loucheur, Carnets Secrets, 1908-1932, presented and annotated by Jacques de Launay, Brussels, Brepols, 1962, p. 71. 2

- Clemenceau, Georges, Grandeurs et misères d’une victoire, Paris,Plon, 1930, 1st edition, p. 209.

- Louis Aubert to André Tardieu, 12 May 1919, p. 10, Fonds Tardieu, PA-AP 166.

- Ralph A. Stone, The Irreconcilables: The Fight against the League of Nations (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1970), 41. Lloyd E. Ambrosius, “Wilson, the Republicans, and French Security after World War I,” Journal of American History 59, no. 2 (1972): 341–352. Priscilla Roberts, “The Anglo-American Theme: American Visions of an Atlantic Alliance, 1914–1933”, Diplomatic History, Summer 1997, Vol. 21, No. 3 (Summer 1997), pp. 333-364.

- William C. Widenor, Henry Cabot Lodge and the Search for an American Foreign Policy, UCP, 1980, pp. 295-297.

- Woodrow Wilson, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson, ed. Arthur S. Link et al., 69 vols. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1966–1993), vol. 61, p. 376. Lippmann believed that if Wilson had presented the League of Nations as a means of perpetuating peace and the balance of power that came with victory, the American people would undoubtedly have accepted it (W. Lippmann, U.S. Foreign Policy: Shield of the Republic, Little, Brown, 1943, p. 37).

- Senate speech, July 10, 1919, PWW, vol. 61, p. 436.

- Thomas A. Bailey, Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal, Macmillan, 1945, p. 277.

- Patrick Weil, The Madman in the White House, Simund Freud, Ambassador Bullitt and the Lost Psychobiography of Woodrow Wilson, Harvard University Press, 2024.

- Antony Lentin, ‘Une aberration inexplicable’? Clemenceau and the abortive Anglo‐French guarantee treaty of 1919. Diplomacy & Statecraft, 8(2), 1997, 33. https://doi.org/10.1080/09592299708406042

- French MFA Archives, Papiers Charles-Roux, MAE/PA-AP 37/2.

- “Clemenceau plain talk”, Nashville Tennessean, 23 November 1922.

- Crucy, F., cited article.

- Bonsal, Stephen, “What Manner of Man was Clemenceau”, World’s Work, February 1930, p. 72.

- Soutou, Georges-Henri, “La France et l’Allemagne en 1919”, in Bariéty, Jacques, Guth, Alfred, Valentin, Jean-Marie, La France et l’Allemagne entre les deux guerres mondiales, proceedings of the conference of January 15-17, 1984, Nancy, PUN, 1987, pp. 9-19 and Ulrich, Raphaële, in Boyce, Robert, French Foreign and Defense Policy 1918-1940, London, Routledge, 1998; Aballéa, Marion, “Une diplomatie de professeurs au cœur de l’Allemagne vaincue. The Haguenin Mission in Berlin (March 1919-June 1920)”, Relations internationales, 150, 2012.

- Bonsal, Stephen, cited article, p. 72.

- Le mémorial de Foch, mes entretiens avec le Maréchal by Raymond Recouly, Paris, les Editions de France, 1929, p.195.

- Idem, p. 196.

- Clemenceau, Grandeur et Misère, p. 2082

- Idem, p. 209.

- Idem, p. 212.

citer l'article

Patrick Weil, A Mad President Breaks the Atlantic Alliance—A Forgotten History, Mar 2025,