Election to the Swiss National Council, 22 October 2023

Anke Tresch

Associate professor of political sociology at the University of LausanneIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Anke Tresch

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

Context

In Switzerland, elections to the National Council, the parliament’s lower house, customarily take place on the penultimate Sunday in October, on the same day as the first round of elections to the upper house, the Council of States. Switzerland has a balanced bicameral system in which both houses of parliament, the National Council and the Council of States, have equal prerogatives. Each of the 26 cantons is its own electoral district for the election of the two houses of parliament. The National Council, which represents the entire voting population, has been elected by proportional representation since 1919. Every four years, its 200 seats are distributed among the cantons in proportion to their population, with each canton having at least one seat. The Council of States represents the cantons, each of which is assigned two seats, with the exception of the former so-called “half-cantons” that send only one MP to the Council. Elections to the Council of States are governed by cantonal law, which in most cases prescribes majority voting 1 . The Council of States remains the stronghold of the Christian Democrats (CVP) and Liberals (FDP), while in the National Council, the Swiss People’s Party (SVP, right-wing) and the Socialist Party (SP, left) have held significantly more seats than the CVP and FDP since the 1999 elections.

From the mid-1990s onwards, the Swiss political landscape underwent a profound change with the rise of the SVP. However, between two successive elections, the parties’ vote shares have changed only slightly, by 2 to 3 percentage points. Against this background, the results of the 2019 National Council elections were historic: the Greens increased their share of the vote by 6.1 percentage points and, with 17 additional mandates in the National Council, achieved the biggest increase in seats of any party since the introduction of a PR system in 1919, while the SVP lost 12 seats, down by 3.8 percentage points. The other three parties in the collegial government — the Liberals (FDP), the Christian Democrats (CVP) and the Social Democrats (SP) — also recorded their worst election results to date. The CVP, a party that had traditionally enjoyed a broad voter base, was overtaken for the first time by the Greens as the fourth-largest political force, and merged in January 2021 with the Conservative Democratic Party (BDP) to form the new party “The Center.” The country’s other Green party, the Green Liberals (GLP), founded in 2007 at national level, was also among the winners of the 2019 National Council elections, with a vote share increase of 3.2 percentage points. Women’s representation reached its highest levels ever, with 42% of female MPs in the National Council and 26% in the Council of States.

The 2019-2023 legislative period was marked by multiple crises (Heidelberger, 2024). Just a few months after the 2019 elections, the Federal Council and Parliament were faced with the challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences. In March 2020, the Federal Council passed an order imposing countrywide lockdown measures without seeking parliamentary approval, and granted extensive financial support to companies and economic sectors most strongly hit by the pandemic. Parliament interrupted its Spring session and cancelled the popular vote scheduled for the following May. In September, Parliament passed the “COVID-19 law,” which immediately came into force. Several associations and political groupings launched a referendum in an attempt to repeal the law and its two subsequent revisions. While initially supportive of the bill, the SVP was eventually the only party on the Federal Council to take sides with the opponents of anti-COVID measures by rejecting the two revisions of the emergency law. The Pandemic Act and its revisions were, however, accepted in the three popular votes that ensued (in June 2021, November 2021 and June 2023), with percentages of “yes” votes ranging from 62 to 69%. Despite these defeats at the ballot box, political groupings opposing COVID-related restrictions ran in the federal elections in several cantons. As the epidemiological situation normalized, Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, which began in February 2022, triggered lively discussions about the direction of the country’s foreign policy and Swiss neutrality. After a moment’s hesitation, Switzerland took up the EU sanctions against Russia and, for the first time, activated its special protection status S to support Ukrainian refugees. As a direct result of the war in Ukraine, Switzerland faced the threat of an energy shortage. This led not only to higher energy prices, but also to a general rise in the cost of living and a decline in purchasing power, which was highlighted by the SP in its election campaign. In March 2023, the emergency takeover by UBS of Switzerland’s second-largest bank, Credit Suisse, was made possible by a loss coverage guarantee from the Swiss Confederation and liquidity loans from the Swiss National Bank (SNB), sparking controversy.

The electoral campaign

From the 2007 elections onwards, the number of candidates and lists filed in Swiss elections rose sharply (Lutz & Tresch, 2022: 524). In 2023, new records were reached with a total of 5,909 candidates running on 618 lists in the twenty cantons with proportional representation (FSO, 2023a) 2 . Compared with the 2019 elections, this corresponds to an increase of 27% for candidates and 21% for lists, with the share of women remaining virtually unchanged at around 41%. The main reason for this increase in the number of candidates and lists is the fact that the major parties, particularly the Greens and Center, have been running in all cantons with several partial lists (separated by age, region, or gender) to address specific electorates in a more targeted manner. Thematic sub-lists (e.g. the Green Liberals’ “Animals and Nature” list) were a novelty in several cantons.

During the election campaign, the opportunity of list apparentments (Listenverbindungen, apparentements de listes) was a subject of intense discussion among right-of-center parties. When two or more parties link their lists, these lists are initially considered as a single electoral list when seats are allocated. This mechanism limits the loss of votes for individual parties. Traditionally, the SP and the Greens have linked their lists in virtually all cantons where proportional representation is used. In the past, the SVP has mainly established list pairings with small right-wing parties (EDU, Lega, MCG), but rarely with the FDP. However, after this lack of pairings caused it to lose eight seats in the National Council in the 2019 elections (FSO, 2021), in 2023 the SVP sought new alliances. Initially, it tried to ally itself in several cantons with the newly-formed anti-sanitary measures parties. Facing criticism from the FDP for this move, the SVP eventually decided against such a strategy, instead establishing for the first time list alliances with the FDP in nine cantons (OFS, 2023b).

The new transparency rules for political financing were applied for the first time in the 2023 National Council elections. In accordance with Chapter 5b of the Federal Law on Political Rights, parties were required to disclose all donations in excess of CHF 15,000 per donor, their receipts, as well as contributions from members of parliament and other elected party officials. The same applied to campaign participants and political organizations whose expenses in the National Council election exceeded CHF 50,000. In 2023, the parties declared total campaign budgets amounting to 54 million Swiss francs and donations of 12 million Swiss francs to the Swiss Federal Audit Office (SFAO) 3 . The largest amounts were declared by the FDP and SVP (around 11 to 12 million francs each), followed by the SP and Center (7 to 8 million francs each). The Greens (3.5 million) and the Green Liberals (3 million) also had budgets amounting to several million francs, while the other parties had to make do with a few tens or hundreds of thousands of francs. Only 2% of candidates, i.e., 119 individuals, were subject to the publicity obligation after investing over 50,000 francs in their own campaign.

Unlike the 2019 and 2015 national elections, when the issue of climate change played a central role, no single issue dominated the 2023 election campaign. According to the survey conducted on behalf of SRG SSR on election day, three issues were of particular concern to voters: rising health insurance premiums, climate change and immigration. In late September 2023, the Minister of the Interior announced that health insurance premiums would rise by an average of 8.7% for basic insurance in 2024, the highest increase in 20 years. This announcement caused concern among a large part of the population, against a backdrop of generally rising prices and steadily declining purchasing power. Rising health insurance costs therefore overtook climate change as the most frequently cited “challenge for Switzerland” in opinion polls. Nevertheless, after record summer temperatures and various natural disasters, climate change remained an important theme in all regions of the country. Compared to 2019, however, the climate movement lost momentum: on the one hand, the national climate demonstration at the end of September 2023 resulted in a significantly lower mobilization than four years earlier; on the other, a series of road blockades by climate activists caused public discontent. Conversely, immigration gained in importance compared to the 2019 elections. In September 2023, Switzerland’s official population passed the symbolic 9 million mark for the first time. This prompted the SVP to launch a popular initiative to limit the permanent resident population to 10 million by 2050. During the election campaign, the party presented the rising number of asylum applications in the country as “asylum chaos,” and ran election spots targeting criminal immigrants.

Voter turnout and party results

Voter turnout has declined steadily in Switzerland since the introduction of proportional representation in 1919, before stabilizing at between 45% and 50% since the late 1990s (Lutz & Tresch, 2022: 528). In 2023, 46.7% of voters turned out in the National Council election, a slight increase of 1.6 percentage points with respect to the 2019 election. As usual, turnout was highest in the canton of Schaffhausen, where voting is compulsory (61.6%). In international comparison, Switzerland is one of the countries with the lowest voter turnout. This is due, in part, to the highly developed opportunities for direct-democratic participation between elections, but also to the limited impact of election results on government formation (Blais, 2014).

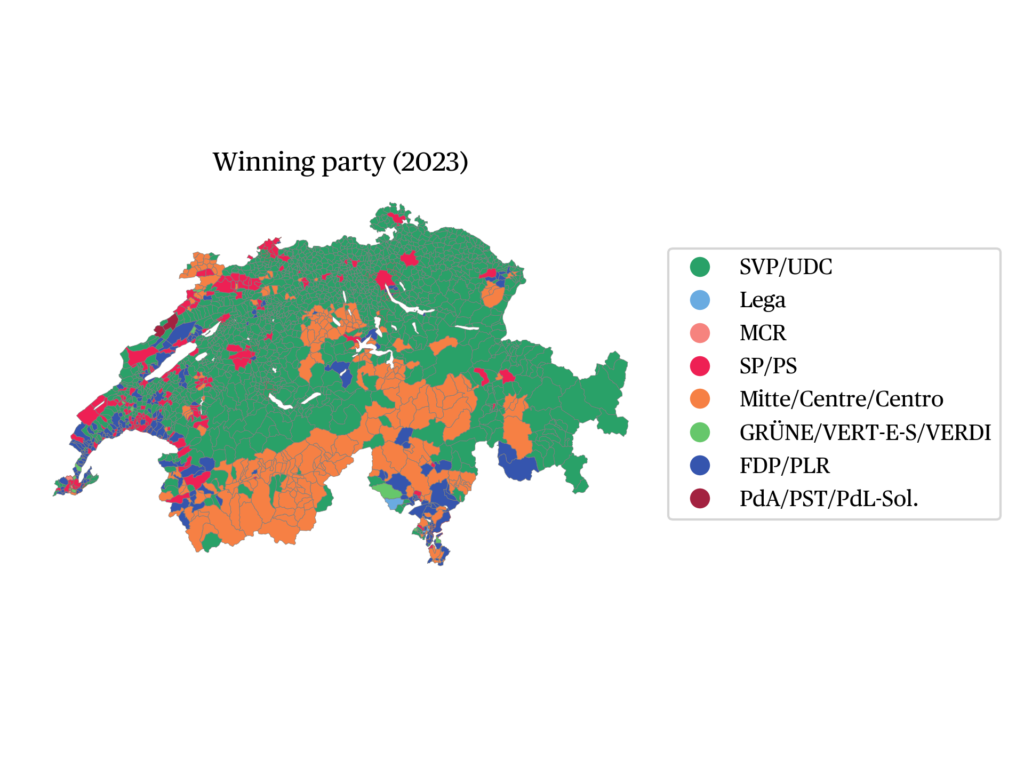

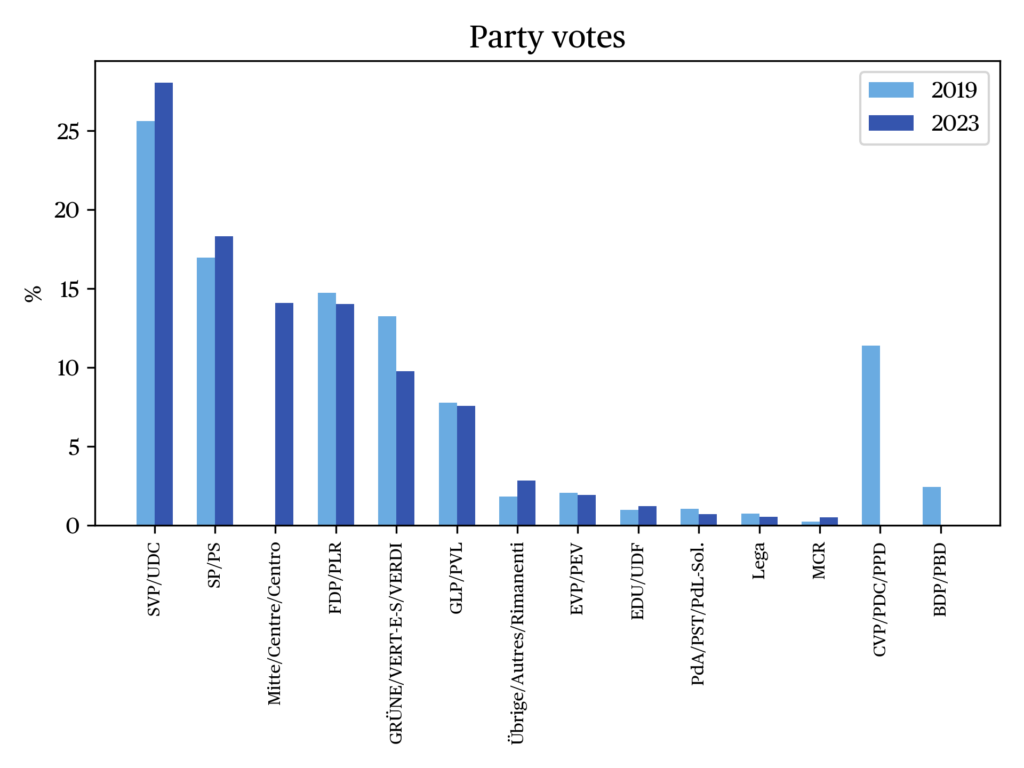

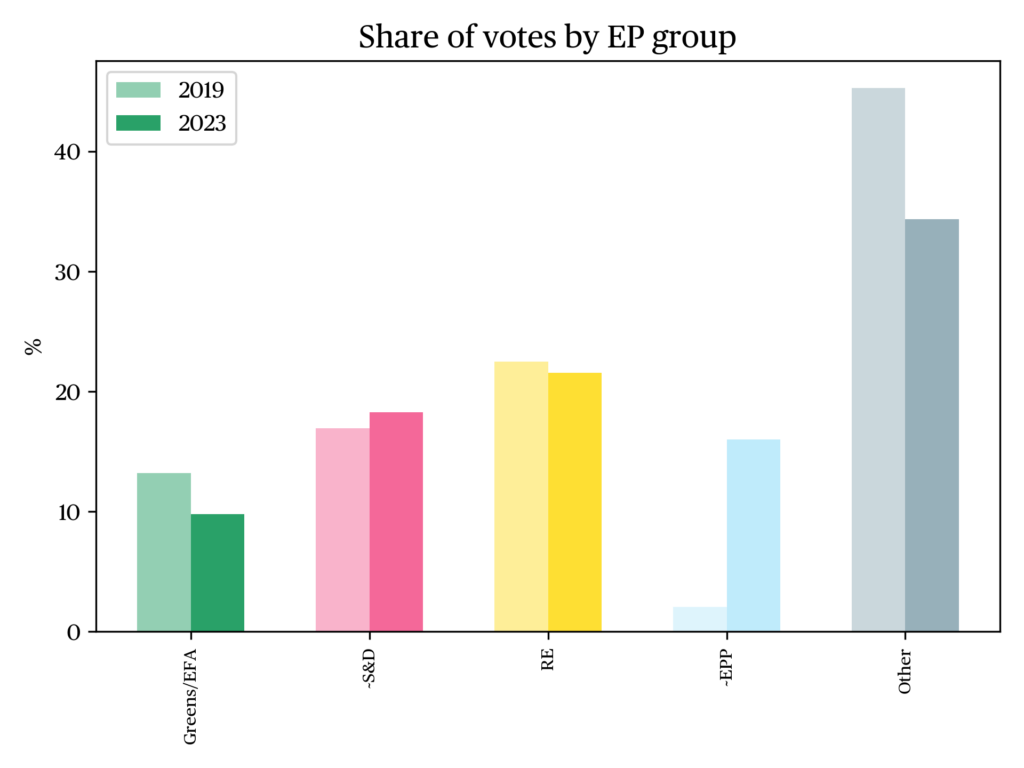

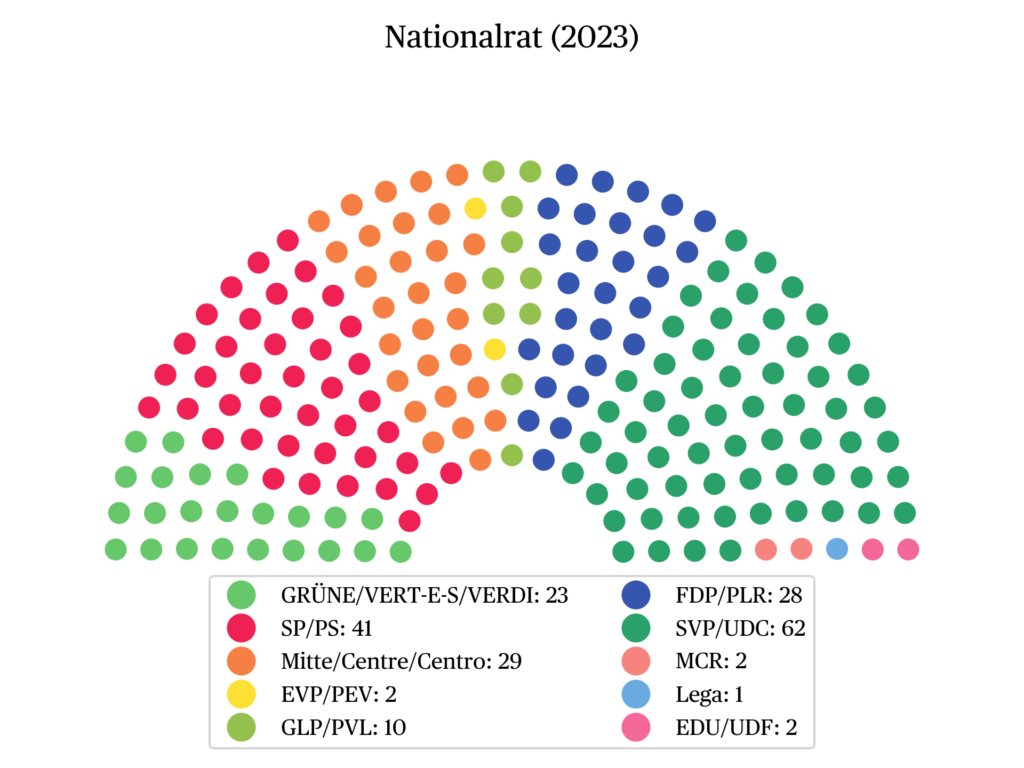

The National Council elections of 2023 resulted in a slight shift to the right and can therefore be regarded as a form of “corrective” to the leftward shift observed in 2019 (Bernhard, 2024). After suffering heavy losses in 2019, the right-wing conservative SVP emerged as a clear winner from the 2023 elections, gaining 2.3 percentage points and winning 9 additional seats. While the SVP was unable to fully make up for its losses in 2019, it nonetheless achieved the second-best result in its history with a vote share of 27.9%. The UDC gained ground across the country, but its growth was strongest in the rural and suburban communities of French-speaking Switzerland.

The SP, that lost votes in 2019, can be counted among the winners of the 2023 election. The Socialists managed to increase their electoral strength by 1.5 percentage points to 18.3% and win 2 additional mandates. The SP made its biggest gains in the country’s five largest cities (Zurich, Bern, Basel, Lausanne and Geneva). With this result, the SP has clearly confirmed its position as Switzerland’s second-largest party, all the more so as its main competitor for this position, the FDP, continued its decline. With a loss of seats and a share of the vote of just 14.3% (-0.8 pp), the FDP has reached an all-time low since the introduction of PR in 1919. It overtook the new Center party by a very narrow margin. The latter won 14.1% of the vote, up 0.3 pp with respect to the combined vote shares of its predecessors, the CVP (11.4%) and BDP (2.4%), in the 2019 election. All in all, the four governing parties improved slightly on their 2019 result and now have a combined vote share of 74.6%.

On the other hand, the big winners of the 2019 elections suffered heavy losses. The Greens collapsed by 3.4 percentage points and fell back below the 10% threshold. However, thanks to a favorable distribution of seats, they lost only 5 of their 28 mandates and now have 23 members in the National Council. Conversely, the Green Liberals only lost 0.2 pp in the popular vote (to 7.6%), but lost six seats (to 8). Despite persistent public concern about climate change, the “green wave” that started in 2019 has thus come to a halt.

There have also been changes among the smaller parties. The radical left lost its two mandates and is no longer represented in Parliament. At the other end of the political spectrum, the right-wing populist Mouvement Citoyen Genevois (MCG) entered the National Council, winning two seats. Among the religious parties, the centrist Evangelical People’s Party (EVP) lost one seat, while the Federal Democratic Union (EDU, Christian conservatism) gained one. Finally, the Lega dei Ticinesi was able to retain its single seat, while the anti-lockdown parties failed to win any seats.

Overall, the right-wing bloc comprising the SVP, FDP and the smaller right-wing parties EDU, Lega, and MCG emerged stronger from the election. However, unlike in 2015, it failed to achieve an absolute majority of 95 seats in the National Council. As a result of the strengthening of the right at the expense of the left and Greens, the share of female MPs in the National Council fell to 38.5% down 4 points from its 2019 record (42%), which nevertheless corresponds to the second highest figure since the introduction of women’s suffrage in 1971.

In the Council of States, on the other hand, the share of women continued to rise, reaching a new record high at 34.8%. The distribution of mandates between the parties, on the other hand, changed little: the Center gained two seats, the Greens and the MCG one seat each, while the Green Liberals lost two and the FDP one. The winners of the National Council elections, the SVP and SP, retained their 6 and 9 seats respectively. In contrast to the situation in the National Council, the center-left, comprising the Center, the Greens, the SP and the Green Liberals, holds a majority in the Council of States with 28 seats.

Government formation

In Switzerland, federal elections do not normally have a direct impact on the government’s composition. Incumbent members of the Federal Council are generally confirmed in office when they stand for re-election, and, according to an unwritten rule of the Swiss concordance system, the four largest parties in the National Council distribute the Federal Council’s seven seats among themselves according to the “magic formula” that allocates two seats to each of the three largest parties and one seat to the fourth-largest party (Sciarini, 2023: chap. 4). However, the magic formula has come under increased pressure since the 2019 election, when the Greens replaced the CVP as the fourth-largest party for the first time, but their President Regula Rytz’s bid for Federal Councillor failed. Before the 2023 election, the Greens had again declared their claim to a seat in the Federal Council should they obtain at least 10% in the popular vote – coveting one of the seats held by the FDP rather than that of SP Federal Councillor Alain Berset, who resigned in June 2023. Although the Greens narrowly missed their 10% target, after a short period of hesitation they finally decided to run in the Federal Council elections with their National Councillor Gerhard Andrey, taking on the seat of FDP Federal Councillor Ignazio Cassis. Following the Greens’ electoral defeat, however, the other parties contested their right to a seat on the Federal Council. In view of the election results, it could have appeared more logical to award a second seat to the Center at the expense of the FDP: although the Center had obtained a slightly weaker result than the FDP, it held five more seats in total in the Federal Assembly comprising the National Council and the Council of States. However, the Center’s president made it clear on election night that his party had no intention of challenging any of the outgoing Federal Council members for a second seat.

Given this situation, it is hardly surprising that all of the current Federal Councillors have been confirmed in office on December 13, 2023. SP representative Beat Jans was elected to replace the resigning SP Federal Councillor Alain Berset. However, if one of the two FDP members of the Federal Council resigns, the current “magic formula” will once again come under pressure.

Conclusion

After a “green wave” (Bernhard, 2020) in the 2019 election, the 2023 National Council election saw a form of rebalancing. The national-conservative SVP emerged victorious from the 2023 elections with 27.9% of the vote (+2.3 pp), while the Greens suffered a significant defeat (-3.4 pp). Slight Social Democratic gains did not offset Green losses, leading to overall weakening of the left-wing bloc. Compared to 2019, however, the changes were less significant. They were even less significant in the Council of States, where the center-left was able to retain its majority.

The SVP’s electoral success in the National Council follows in the wake of recent electoral victories by right-wing populist parties in Western Europe, such as Fratelli d’Italia in Italy, the Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Netherlands, the Sweden Democrats (SD) in Sweden and the Finns’ Party. The SVP is the representative of this political family with the largest share of the vote nationally. The SVP’s single-issue election campaign, focusing on migration against a backdrop of rising population numbers and asylum applications, seems to have borne fruit. Whether this election result translates into a tougher migration and asylum policy will depend, however, on the willingness of the FDP and Center parties to cooperate with the SVP in Parliament, but also on the outcome of popular votes. With the strengthening of parties on both sides of the political spectrum in the National Council – the SVP on the right and the SP on the left – polarization within the Swiss party system has increased. The number of projects supported jointly by the four governing parties in Parliament can thus be expected to continue its decline in the next legislative period (Sciarini, 2023: 300, 303). The next legislature will therefore get off to a tricky start. This is especially true on the all-important issue of the new Framework Agreement with the European Union, with both the SP and SVP being extremely critical of the Federal Council’s negotiating mandate for a new cooperation agreement with the EU.

The data

References

Bernhard, L. (2020). The 2019 Swiss federal elections: the rise oft he green tide. West European Politics 43(6): 1339-1349.

Bernhard, L. (2024). The 2023 Swiss federal elections: the radical right did it again. West European Politics.

Blais, A. (2014). Why is turnout so low in Switzerland? Comparing the attitudes of Swiss and German citizens toward electoral democracy. Swiss Political Science Review 20(4): 520-528.

Federal Statistical Office (2023a). National Council elections 2023: lists and candidacies. Neuchâtel: Federal Statistical Office. Online.

Federal Statistical Office (2023b). Nationalratswahlen: Listenverbindungen nach Parteien. Neuchâtel: Federal Statistical Office. Online.

Swiss Federal Statistical Office (2021). Nationalratswahlen 2019: Mandatsgewinne und -verluste aufgrund von Listenverbindungen. Neuchâtel: Federal Statistical Office. Online.

Heidelberger, A. (2024). Ausgewählte Beiträge zur Schweizer Politik: Rückblick auf die 51. Legislatur: Vom Umgang des politischen Systems mit (grossen) Krisen, 2023. Bern: Année Politique Suisse, Institut für Politikwissenschaft, Universität Bern.

Lutz, G. & Tresch, A. (2022). Die nationalen Wahlen in der Schweiz. In Papadopoulos, Y., P. Sciarini, A. Vatter, S. Häusermann, P. Emmenegger, & F. Fossati (eds.). Handbuch der Schweizer Politik – Handbook of Swiss Politics (pp. 519-557). Basel: NZZ Libro.

Sciarini, P. (2023). Swiss politics. Institutions, acteurs, processus. Lausanne: Presses polytechniques et universitaires romandes.

Notes

- In general, an absolute majority of votes is required in the first round, and a relative majority in the second. The cantons of Jura and Neuchâtel allocate their two seats by proportional representation. In the canton of Appenzell Innerrhoden, elections to the Council of States are held at the Landsgemeinde in April of the election year (Lutz and Tresch, 2022). Second-round elections are held from mid-November, at a date that varies from canton to canton.

- Additionally, a much smaller number of candidates stood for election in the six cantons using a single-seat majority system (Uri, Obwalden, Nidwalden, Glarus, Appenzell Ausserrhoden, and Appenzell Innerrhoden).

- The amounts can be found on politikfinanzierung.efk.admin.ch.

citer l'article

Anke Tresch, Election to the Swiss National Council, 22 October 2023, Jun 2024,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue