Parliamentary election in Denmark, 1 November 2022

Karina Kosiara-Pedersen

Associate Professor at University of CopenhagenIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Karina Kosiara-Pedersen

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

The context of the election

At the 2019 election, Mette Frederiksen from the Social Democrats (Socialdemokratiet) acquired the keys to the Prime Minister’s Office with the support of the centre-left parties (Red-Green Alliance, Socialist People’s Party and Social Liberals). The minority, one-party government successfully (in an international perspective and according to the electorate) handled the Covid-19 pandemic and there was for a while a ‘rally around the flag’ trend. However, the Covid-19 handling also included closing down the mink industry, including killing all minks, and not all decisions on this were legal. A minister stepped down, but the opposition put Mette Frederiksen and her role in the spotlight. A commission investigated this, and in light of the report from the “Mink commission”, the Social Liberals (Radikale Venstre) announced on 2 July that they required Mette Frederiksen to call the election prior to the opening of the parliament season on the first Tuesday in October. Otherwise, they would withdraw their support, whereby the government would fall. Hence, the election campaign had already begun when the Prime Minister (on 5 October) called the election for 1 November 2022. The regular general election was to be held on 4 June 2023 the latest, and given her scores in the polls there is no doubt that Mette Frederiksen would have preferred to wait.

Lots of (new) parties

A high number of parties, 13 in total, fielded candidates across the ten electoral districts for the 175 seats in parliament elected in Denmark (in addition to these 175 seats, four MPs are elected in Greenland and the Faroe Islands). Eleven parties elected in 2019 were still represented in parliament, and the Christian Democrats (Kristendemokraterne) stood for election as they have since 1971. In addition, new parties had been formed. MPs had left the Alternative (Alternativet) to create the Independent Greens (Frie Grønne), and two former high-profiled Liberals had launched their own parties.

Lars Løkke Rasmussen, a former Prime Minister, minister and chair of the Liberals (Venstre), left the Liberals on 1 January 2021. In his Facebook statement, he wrote that he had decided to ‘set himself free after 40 years of Liberal membership’. He justified continuing as an independent in parliament, stating that: “Due to my number of personal votes, I’m elected in my own right and will therefore not leave my parliamentary seat” (Rasmussen 2021). At first, Rasmussen formed a political network but in June 2021, the party name, Moderaterne, was approved by the authorities, and by September 2021, they had collected the required number of signatures. In June 2022, the party was formally formed.

Inger Støjberg, a former minister and vice-chair in the Liberals, left the Liberals in light of their support for the ‘impeachment’ (decided February 2021). Støjberg was accused and later convicted for the handling of cases concerning the accommodation of married or cohabiting asylum seekers, one of whom was a minor, which had not taken place in accordance with administrative law rules and principles (Kosiara-Pedersen 2021). When sentenced to six months of unconditional prison in December 2021, Støjberg left parliament upon the sentence and served it in her home in the spring of 2022. In June 2022, she formally formed the party ‘Danish Democrats — Inger Støjberg’ (Danmarksdemokraterne) and broke the record for fastest collection of voter signatures to become eligible to stand for election.

Election results at the party level

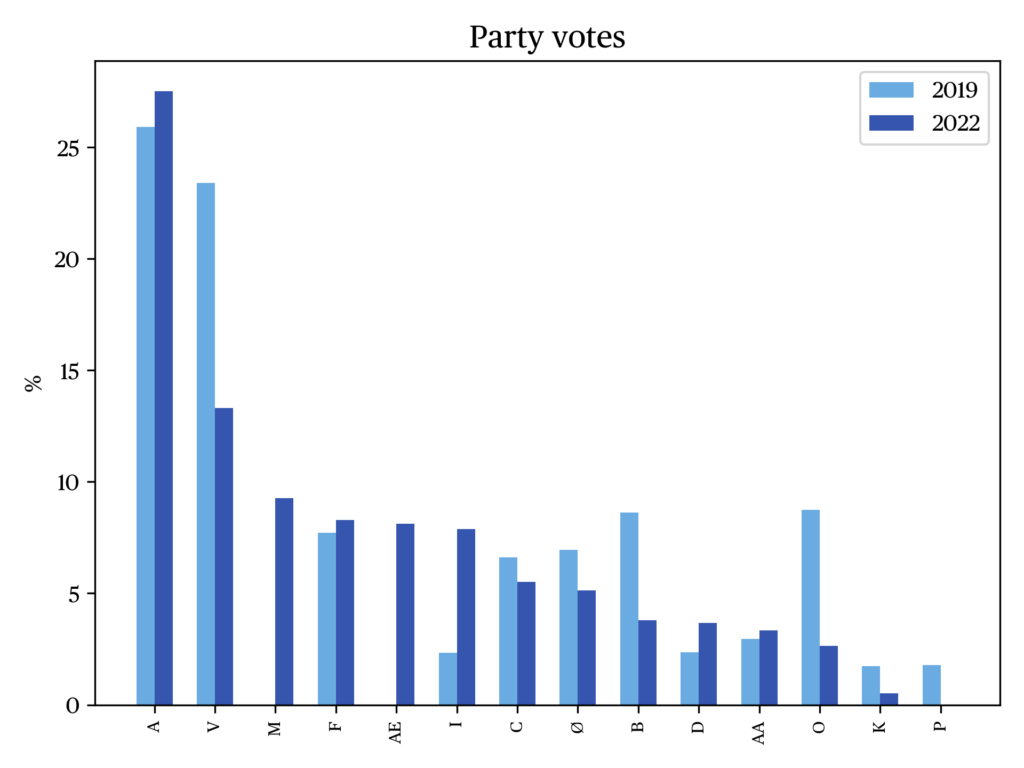

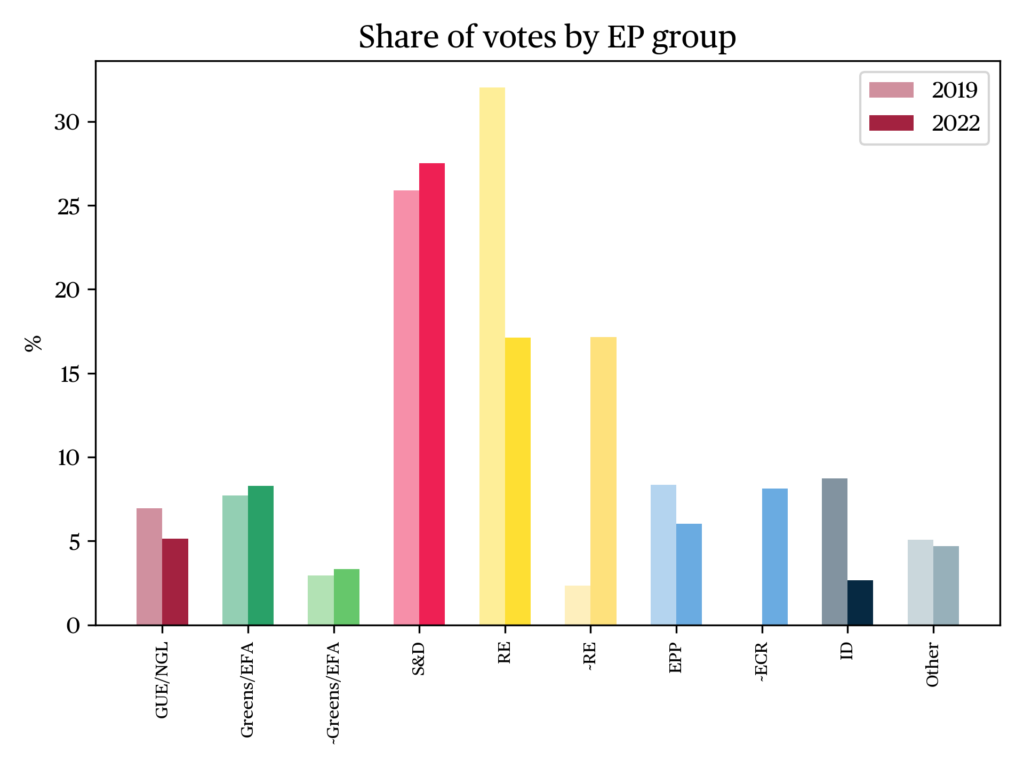

When comparing the election results of 2019 and 2022 (see panel “the data”), two overall results stand out. First, there is only one large party left instead of two. Second, two new parties make it into the top 5 in 2022. However, changes at the party level can be seen as well.

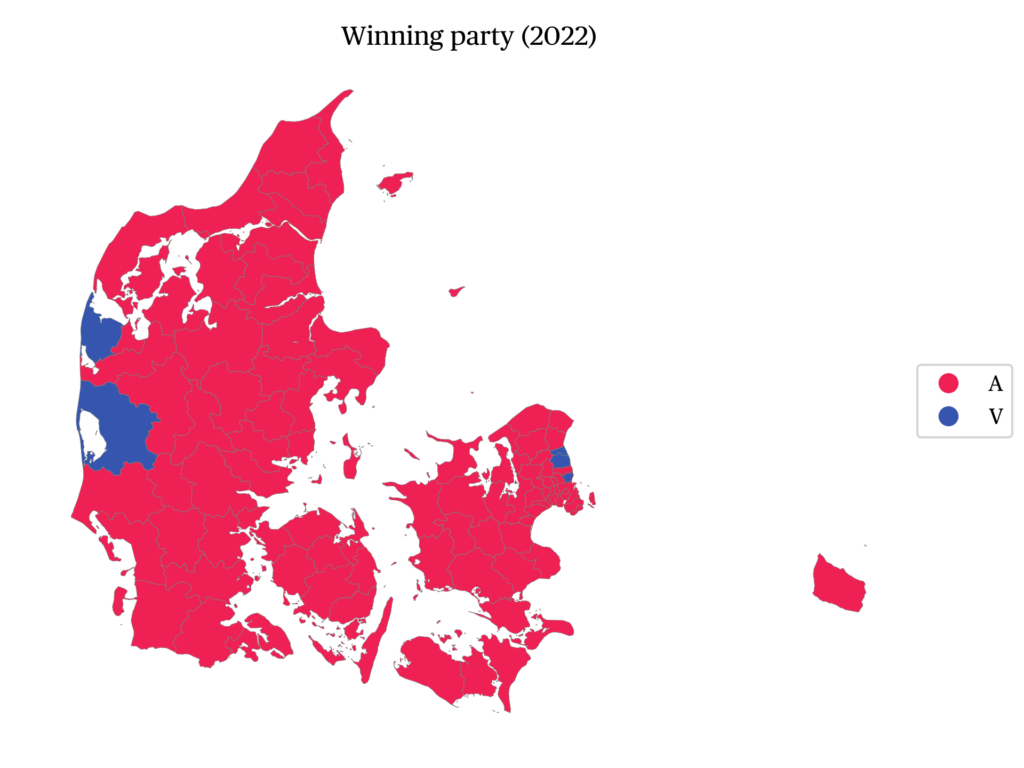

At the 2019 elections, the Social Democrats gained only one seat but acquired the keys not only to the Prime Minister’s office, but to all ministerial offices with the support of the Red-Green Alliance, Socialist People’s Party and Social Liberals (Kosiara-Pedersen 2020). The election period brought unprecedented challenges with the Covid-19 pandemic resulting in a ‘rally around the flag’ tendency and high levels of support for the Social Democrats. However, the joyful period did not last, amongst other things due to the Mink Culling scandal. Hence, at the 2022 election, the Social Democrats gained two seats, which was better than expected. The Social Democrats had struggled in the cities at the 2021 municipal elections, and while, at the 2022 general election, they did less well in densely populated areas, their losses there were not as large as feared.

Among the parties supporting the Social Democratic governmentin parliament, only one party gained electorally in 2022, namely the Socialist People’s Party (Socialistisk Folkeparti, SF), which was considered the closest ally of the Social Democrats. The party gained one seat and now has 15 It thus managed to recover its usual level of support, stabilizing its score after a high of 23 seats in 2007 and a low of seven in 2015, caused by an unsuccessful term in government.

The most left-wing party, the Red-Green Alliance (Enhedslisten) lost four seats and ended with nine. This is a marked decrease, possibly partly explained by some voters choosing to ‘save’ the Alternative. However, this result is still above their electoral record of 1994-2007, where they, with 4-6 seats, were at or close to the electoral threshold.

Since 2001, the Social Liberals (Radikale Venstre) have been on a roller-coaster ride with a doubling and halving of their support at every other election. On this basis, the 2022 decline from 16 to seven could be expected. However, their losses in 2022 have been drastic, and also seem to result from their decision to require an early election — while still pointing to Mette Frederiksen as their preferred Prime Minister.

The Alternative (Alternativet) stormed into parliament with nine seats in 2015 but lost support in 2019 and ended with only five MPs. In 2022, they struggled with the 2 percent electoral threshold prior to the election but eventually made it into parliament with six seats. Some of the additional votes they received may be red-bloc sympathy votes from neighbour parties due to them being so close to the threshold, since opinion polls showed that if they did not make it into parliament, the centre-left would not be able to command a majority.

All parties in the centre-left bloc except the Social Democrats get markedly more votes as the population density increases. They are much stronger in suburban and urban areas. In addition, women, in comparison with men, cast more votes for centre-left parties than for parties right of the centre.

Turning to the right-of-centre parties, the most successful of them is still the Liberals, even if their vote share reduced drastically. In 2019, the Liberals gained seats but their government lost its majority, leading to Prime Minister Lars Løkke Rasmussen being replaced by Mette Frederiksen. In the aftermath of the election, not only Lars Løkke Rasmussen and Inger Støjberg but also other prominent MPs left the Liberals or parliament. Opinion polls show that voters left them as well. The Liberals were struggling under the chairmanship of Jakob Ellemann-Jensen, son of former minister of foreign affairs and Liberal party chair Uffe Ellemann-Jensen. In this light, the electoral loss of 20 seats to a total of 23 seats was expected. But it is no less tough for a party who since 1994 have gotten at least 42 seats, and who saw the 2015 result with only 34 seats as a one-off incident due to issues with Lars Løkke Rasmussen’s expense accounts (Kosiara-Pedersen 2016; 2017). The agrarian backbone of the Liberals is clearly seen in the electoral result, as they are doing markedly better in rural areas than in suburban and urban regions.

The Conservative People’s Party (Det Konservative Folkeparti) doubled its representation from six to 12 seats in 2019, the largest gain in a long time. Due to the turmoil within the Liberals, their support more than doubled in 2021-2022 in the opinion polls. On this basis, their party chair, Søren Pape Poulsen, announced that he was also a Prime Minister candidate. With this came increased media attention and devastating coverage of decisions in his public and private life. Hence, while mid-election period expectations were very high, the loss of only two seats at the 2022 election came as a relief.

Except for the two new parties, the largest gain at the 2022 election was made by the Liberal Alliance (Liberal Alliance). Competing in elections since 2007, they have been roller-coasting from just over the electoral threshold in 2007 and 2019, to 13-14 seats in 2015 and 2022. Their young chair, Alex Vanopslagh, was particularly successful in gaining traction through campaigning on Tiktok, and the Liberal Alliance has been successful with younger voters.

Turning to the three right-wing parties with clear anti-immigration stances, the oldest is the Danish People’s Party (Dansk Folkeparti), created in 1996 as a splinter party from the Progress Party. It became the largest right-of-centre party in 2015, but was more than halved from 37 to 16 seats in 2019. After the 2019 election, the decline continued as the party dissolved, with MPs leaving in the aftermath of the election of Morten Messerschmidt as party chair. Polls indicated that they could land under the electoral threshold. Hence, even though they lost 11 seats in the 2022 election, they were relieved to secure representation with five seats.

The New Right (Nye Borgerlige) made it just above the threshold with four seats in 2019 in what was their first election. A period in clear opposition without marked influence left them rather outside the spotlight, but the turmoil within the Danish People’s Party increased their electoral support in the opinion polls, and they eventually obtained six seats, gaining two.

Danish Democrats gained candidates, MPs and voters from the imploding Danish People’s Party, which may at least partly explain how a party formally registered as late as June 2022 can storm into parliament with 14 seats (8 percent of the vote).

All three right-wing parties are, together with the Liberals, doing markedly better in rural areas than in suburban and urban ones. Their social profiles differ, in that the New Right gets more support from men and younger voters, while the gender balance is more equal in the other two parties, who also attract a large share of older voters.

Two parties stood for election but did not gain representation. The Christian Democrats have stood for election continuously since 1971 but has not gained election since 2001. The Independent Greens was the only green party not standing together with the Alternative at the 2022 election (Kosiara-Pedersen 2023). At 0.5 and 0.9 percent of the votes, they were both far from the 2 percent electoral threshold.

Election result at the system level

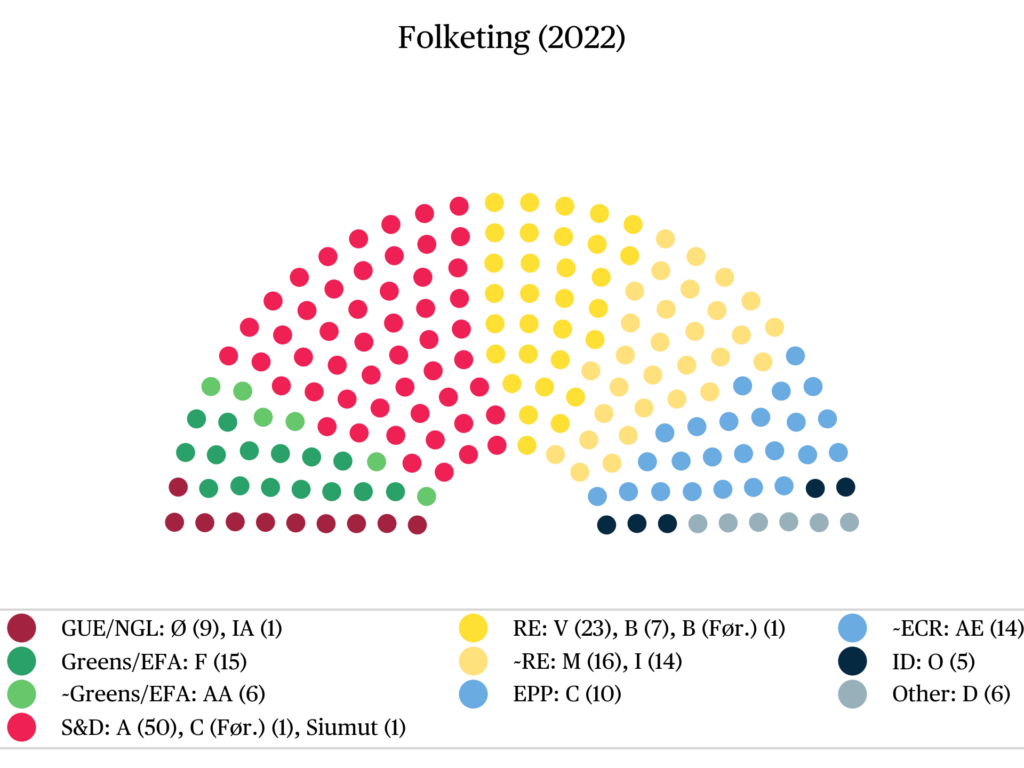

The 2022 election changed the format of the party system. Between seven and eleven parties have been elected to Folketinget since the 1973 election doubled the number of parliamentary parties from five to ten. After the 2022 election, 12 parties are represented in parliament.

At the core of the party system, the four old parties (Social Democrats, Liberals, Conservatives, and Social Liberals) regained their strength in 2019 with 68 percent of the seats after a major loss in 2015 (49 percent). However, in 2022 they are back to 2015 levels with 51 percent. This is markedly lower than at the 1973 election, in which these four parties got 59 percent of the seats. While keeping its monopoly on the Prime Minister’s office, the old core of the Danish party system is being challenged (Kurrild-Klitgaard and Kosiara-Pedersen 2018).

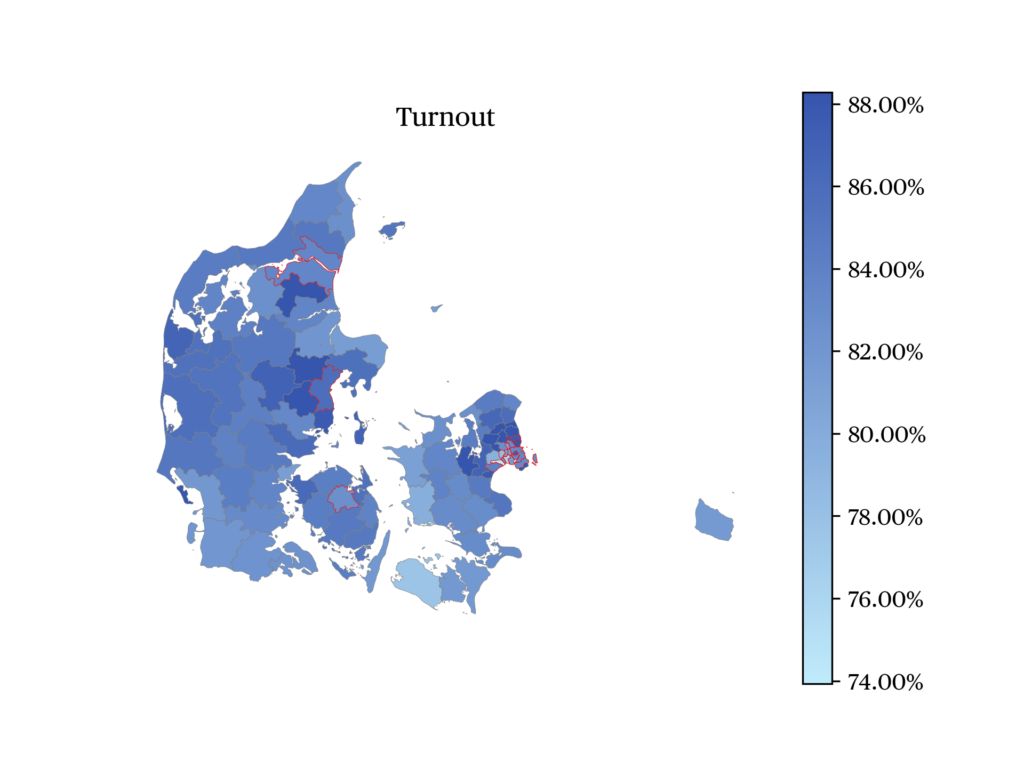

In an international comparison, turnout in Denmark is high (Hansen 2020), but it saw a (further) drop from 85.9 percent in 2015 and 84.5 percent in 2019 to 84.2 percent in 2022. The downward trend is clear, even if more modest than in other European countries.

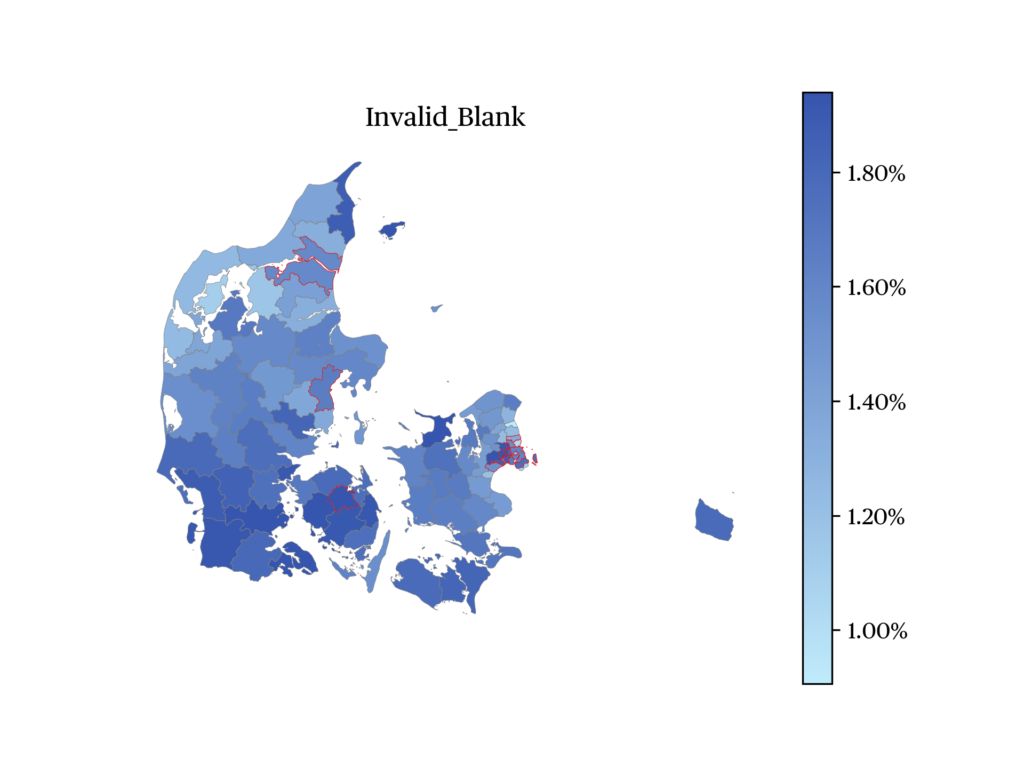

The share of invalid votes has been increasing for the past fifty years, but the 2022 election saw a marked increase both in the share of total invalid votes and in the share of blank votes (Hansen 2023). 1.3 percent of the Danish voters turned up but refrained from supporting any of the 13 parties and their candidates on the ballot. The share of invalid votes is higher in the southern part of Denmark, but there is no clear pattern across urban and rural areas.

Government formation

As regards government formation, the 2022 election also brings renewal. After three decades of long-serving Prime Ministers (Conservative-led right-of-centre government 1982-1993, Social Democratic-led centre-left 1993-2001, Liberal-led right-of-centre 2001-2011), the government has shifted side at all elections since 2011. However, the election night left PM Mette Frederiksen’s centre-left bloc of parties with a marginal majority. While the government and its parliamentary basis had a comfortable majority at 92 seats after the 2019 election, not including the five Alternative MPs, who politically is part of the red bloc, the 2022 election saw their seat share decrease to 81. Only with the inclusion of the Alternative and three North Atlantic MPs (two from Greenland and one from the Faroe Islands), did Mette Frederiksen and the centre-left bloc of ‘red’ parties command the minimum majority of 90 seats. Nevertheless, this result preserved her right to form the new government. Mette Frederiksen was appointed formateur after a ‘Queen round’ (where all parties give advice on what government they support), and government negotiations are record long, being still ongoing five weeks after the election.

During the campaign, Mette Frederiksen repeated her message from June 2022, according to which she wanted to pursue a government formed across the two traditional blocks. At the time of writing, it seems as if she will succeed. The negotiations point towards a Social-Democratic led government with the Liberals, with the parliamentary support of the Moderates. This will be a historic government as the Social Democrats and Liberals have only collaborated in government once, in 1978-1979, in a political experiment that was not very successful. The implications of the advent of a centre government are extremely interesting. While Danish parliamentary affairs are well-known for a high level of consensus with broad support for a large share of the legislation, the government will be challenged by opposition parties from both the right and left, as well as from within, as ministers from the two sides are to agree and trust each other. Due to the high level of consensus among the majority of the parties on EU, foreign and defence policies, the government formation will only have little impact in these arenas.

References

Hansen, K. M. (2020). Electoral Turnout. Strong Social Norms of Voting. In Christiansen, P. M., Elklit, J., & Nedergaard, P. (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Danish Politics, Oxford: OUP, 76-87.

Hansen, K. M. (2023). Folketingsvalget 2022. København: DJØF Forlag.

Kosiara-Pedersen, K. (2016). Denmark. European Journal of Political Research. Special Issue: Political Data Yearbook, 55: 1, 76–83.

Kosiara-Pedersen, K. (2017). Denmark. European Journal of Political Research. Special Issue: Political Data Yearbook, 56: 1, 79–84.

Kosiara-Pedersen, K. (2019). Denmark: Political Development and Data for 2018. European Journal of Political Research. Special Issue: Political Data Yearbook, 58: 1.

Kosiara-Pedersen, K. (2020). Stronger core, weaker fringes: the Danish general election 2019. West European Politics, 43: 4, 1011-1022.

Kosiara-Pedersen, K. (2023). The Danish general election 2022. West European Politics, 46.

Kosiara-Pedersen, K. & Kurrild-Klitgaard, P. (2018). Change and stability in the Danish party system. In Lisi, M. (eds.), Party system change, the European crisis and the state of democracy. Routledge Studies on Political Parties and Party Systems, London; N.Y.: Routledge, 63-79.

Rasmussen, L. L. (2021). Statement on Facebook from 1 January 2021. Retrieved on 25.4.2022.

citer l'article

Karina Kosiara-Pedersen, Parliamentary election in Denmark, 1 November 2022, Mar 2023, 145-149.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue