Parliamentary election in Italy, 25 September 2022

Issue

Issue #3Auteurs

Carolina Plescia , Sofia Marini

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

Introduction

On the 25th of September 2022, a snap election took place in Italy. In a rushed political campaign, mainly revolving around coalition (dis)agreements, Italians were called to renew both Chambers of Parliament. Despite the technicalities of the electoral system and the substantial reduction in the number of MPs added some uncertainty to the final election results, there was little surprise as to who would the winner be. As expected, the right-wing coalition obtained a majority of seats in both Chambers. Still, they fell short of the two-thirds majority that would allow them to change the Constitution without the need for a referendum. With an unprecedented speed, the new government headed by Giorgia Meloni was sworn in less than one month after the election. Eventually she became the first woman Prime Minister of the country and her government is possibly the most right-wing in Italian republican history. Nevertheless, in the choice of Ministers she has highlighted continuity with previous right-wing Berlusconi governments and her pleaded Atlanticism reassured international observers.

This article will start by providing a general background of the political developments during the last legislature, that led to the dissolution of Parliament and to early election. It will then proceed to highlight the specificities of the electoral campaign and describe the final results, to conclude with government formation and policy implications thereof.

Background

The parliamentary election held in Italy in March 2018 was followed by the formation of what was regarded by most observers as the “first ‘all-populist’ government in post-war Western Europe” (Newell 2019: 205). The two parties forming the government were the largest party winning the 2018 election with 34% of the vote – the Five Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle, M5S) led by Luigi Di Maio — and Matteo Salvini’s Lega (League, formerly the Northern League), that had emerged as the main political force within the centre-right electoral coalition (with 17% of the votes). Giuseppe Conte, a law professor politically unknown but ideologically close to the M5S, was appointed as Prime Minister. The Conte I government, however, only lasted 14 months. Following the European Parliament (EP) elections held on 26 May 2019, the League became the largest party in Italy and a few months later its leader, Matteo Salvini, hoping for snap election and the possibility to become Prime Minister, triggered a government crisis that led to Conte’s resignation. However, instead of calling for a new election, the President Sergio Mattarella gave Conte a mandate to attempt the formation of an inter-electoral government consisting of the M5S, the centre-left Partito Democratico (Democratic Party, PD) and the left-wing Liberi e Uguali (Free and Equal, LeU) party (Giannetti et al. 2020).

The government Conte II lasted until former Prime Minister Matteo Renzi withdrew his party’s support in early 2021. Upon the resignation of Giuseppe Conte, the mandate was conferred on to Mario Draghi, former President of the Bank of Italy and later of the European Central Bank (ECB). Attracted by plans on how to spend around 200 billion euros from the European Union Recovery fund, 1 the Draghi government received the confirmatory votes of confidence from all the parties represented in parliament except Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy, FdI) and a fringe element of the M5S. The Draghi government would fall into the ‘technocratic-led partisan government’ category, because it included eight technocratic and fifteen partisan ministers (Garzia and Karremans 2021). Investors and beyond hoped that the man widely credited with saving the euro during the 2012 sovereign debt crisis could spearhead reforms to boost growth in a country that has long underperformed its European peers, weighing down the whole Eurozone. However, just a little over than a year later, the Draghi government suffered an irreversible political crisis, triggered initially by the M5S but then sharpened by tense relationships between the members of a patchy and frictious government coalition. After the fall of the government, which led to a parliamentary impasse, President Sergio Mattarella dissolved the parliament on 21st July, and called for new elections.

The campaign

The election campaign was characterized by three main aspects. To begin with, it was the first one in Italy since World War II taking place during the summer. August, arguably the hottest month of the year in Italy, is usually spent in vacation by most Italians with little thought given to politics. Knowing this, political parties only started to really campaign for the election at the beginning of September, making it arguably one of the shortest and less eventful election campaign in Italy’s republican history. Moreover, the timeframe was relatively tight, with just over two months to conduct the political campaign and only one month to finalize coalition choices (and collect signatures to allow new parties to contest the election), since the full lists had to be submitted by end August. The consequence of this was also a relatively limited grassroots mobilization but rather a cementation of the use of digital tools and platforms by political leaders, especially on the right wing of the electoral spectrum.

The second major aspect was the relatively little fragmentation of the otherwise usually very fragmented Italian political system. This was primarily due to the effect of the electoral law which would penalise small parties standing alone. The electoral law commonly known as Rosatellum from the name of its author 2 takes the form of a mixed electoral system in which for both chambers 37% of the seats are allocated by a single-round majority system in as many uninominal constituencies and 61% of the seats are distributed proportionally among coalitions and individual (closed) lists that have passed the required national bar thresholds. 3 Moreover, no split vote is allowed: voters cannot choose a candidate for the single-member constituency that is not associated with the preferred proportional list. The electoral law requires each list to present its own program and declare its own political leader as well as, if necessary, the affiliation with one or more lists in order to create coalitions: the existence of a coalition, which is unique at the national level, binds the coalesced lists to present only one candidate in each uninominal constituency. The partisan affiliation of the candidates in uninominal constituencies and more broadly the formation of pre-electoral coalitions has dominated the election campaign.

While on the right, the formation of the coalition was rather straightforward with the Brothers of Italy (FdI) of Giorgia Meloni, the League of Matteo Salvini and Forza Italia of Silvio Berlusconi coalescing together, on the left the road was bumpier. First there were speculations of the Democratic Party (PD) coalescing with the M5S but they did not last long due to the tense relationship between the leader of the PD Enrico Letta and the leader of the M5S Giuseppe Conte. Rather, Letta signalled his intention to form a coalition with Carlo Calenda and its moderate liberal party Azione (Action) that was polling around 4% at that time. However, leadership incompatibilities as well as Calenda’s openness to Matteo Renzi’s party Italia Viva made the coalition between the three centre-left forces impossible. Eventually, the PD run in a coalition with three smaller parties on the left, all polling around 1-2% (More Europe, +E, Civic Commitment, IC, and the Green and Left Alliance, AVS) while Calenda and Renzi run together within a political force known as Terzo Polo or Third Pole.

The third major aspect of the election campaign was the relatively low importance of policy-related topics compared to the salience that media gave to the pre-electoral coalition formation. Giorgia Meloni, widely regarded as the likely winner of the election, was able to set the campaign agenda by politicizing her winning topics such as poverty, low wages and law and order — specifically linked to illegal immigration. Other parties, and the PD in particular, tried with no success to shift the focus on issues that arguably would weaken Meloni, such as European integration and abortion. In fact, while these two topics were not high on the agenda of many Italians, her positions were clearly at odds with those held by the majority of the population, which is widely seen as much more progressive on these issues compared to the female leader. Yet, arguably, she was able to quickly shift positions on these topics by diffusing her positions and lowering attention. The polls were remarkably stable during the short election campaign and made it clear that FdI was going to win the election with a strong overall parliamentary majority for the right-wing coalition. From this viewpoint, the campaign was primarily fought on post-electoral scenarios.

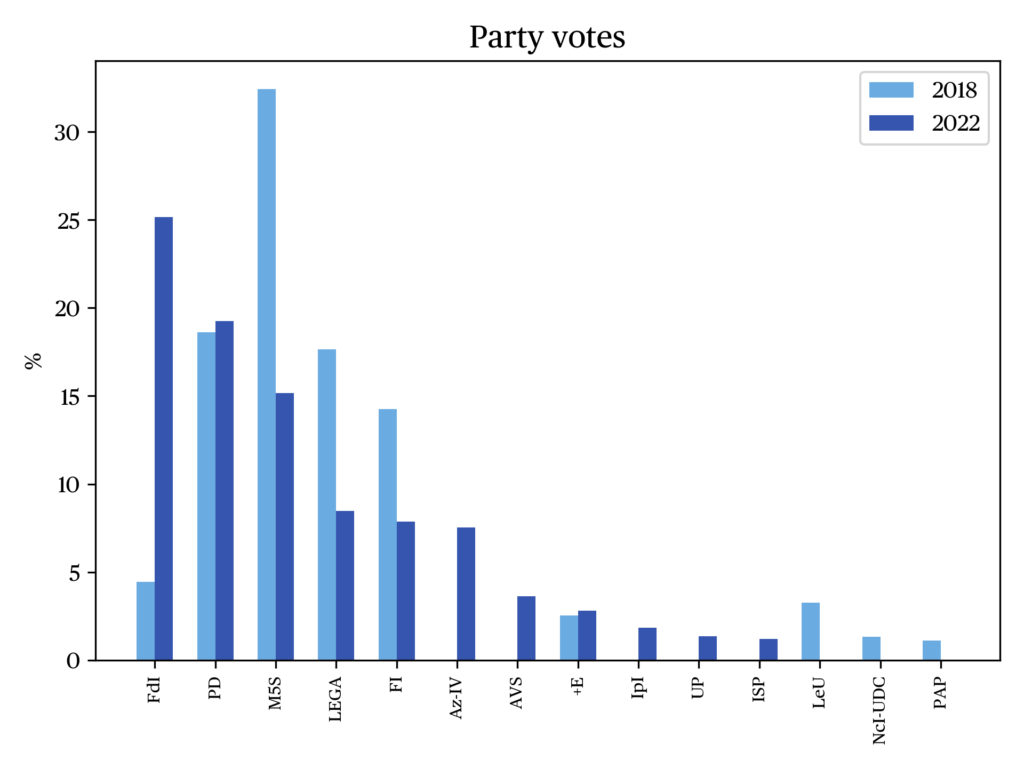

The results

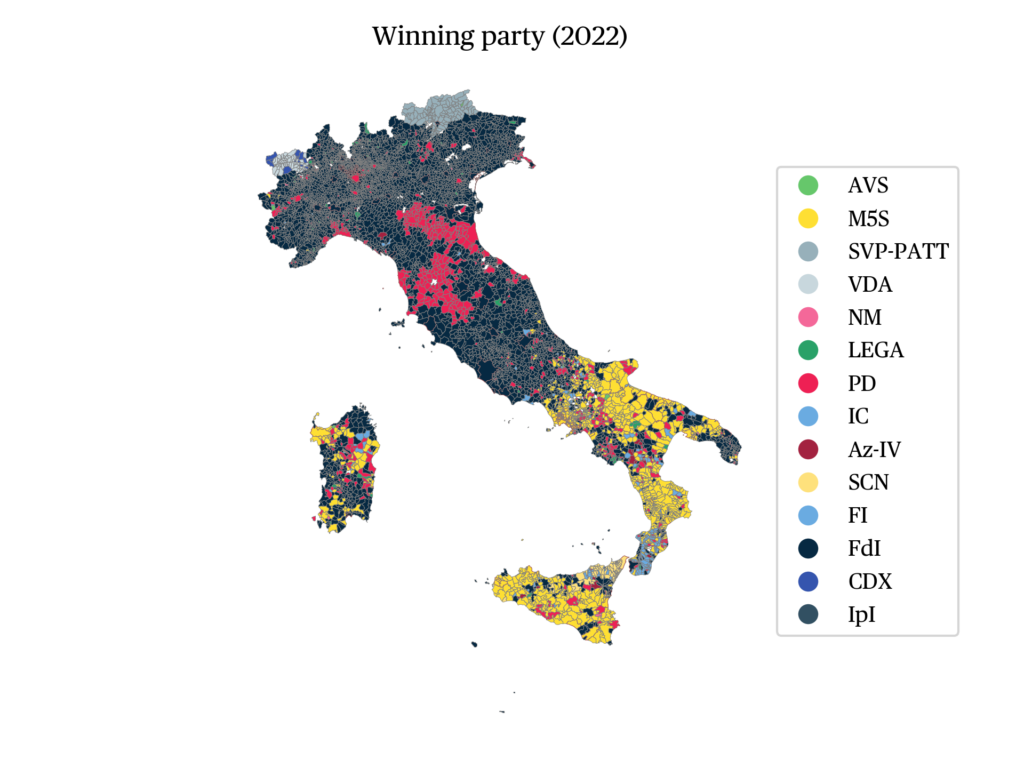

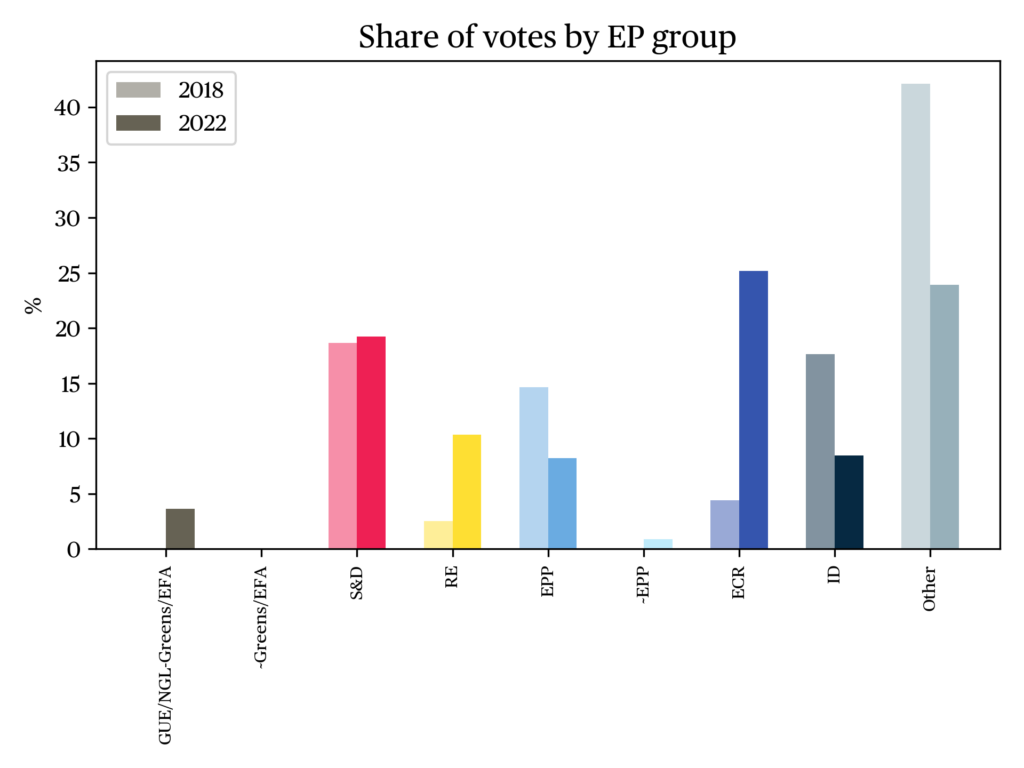

Voter turnout was record-low (63.8%) with certain areas in the South of the country having turnout as low as 30%. This is quite remarkable because Italy has been recording a relatively high election turnout compared to most advanced countries — but this was perhaps not surprising considering the relatively short and uneventful election campaign, as discussed above. Still, it was the largest change in turnout in Republican Italy, with a drop of 9 percentage points compared to the 2018 election (Garzia 2022). The clear and undisputed winner of the election was Meloni’s party FdI with 26% of the vote and a swing of 21.6 percentage points compared to the previous general election of 2018 (see “the data” below). All other parties were clearly losers of the election, since they received less votes than polls had predicted and far less than they had received in 2018. However, no leader admitted defeat except for the leader of the Democratic Party, Enrico Letta, which polled 19.1% of the vote — almost the same as in 2018. The League of Matteo Salvini won 8.8% of the vote, more than 8.5 percentage point less than in 2018; the M5S obtained 15.4% of votes, about 17.3 percentage points less than in 2018 and Berlusconi’s Forza Italia received 8.1% of the votes, down about 5.9 percentage points compared to 2018. The Third Pole (Azione-Italia Viva) won 7.8% of the votes, which was a relatively good result for a new political formation.

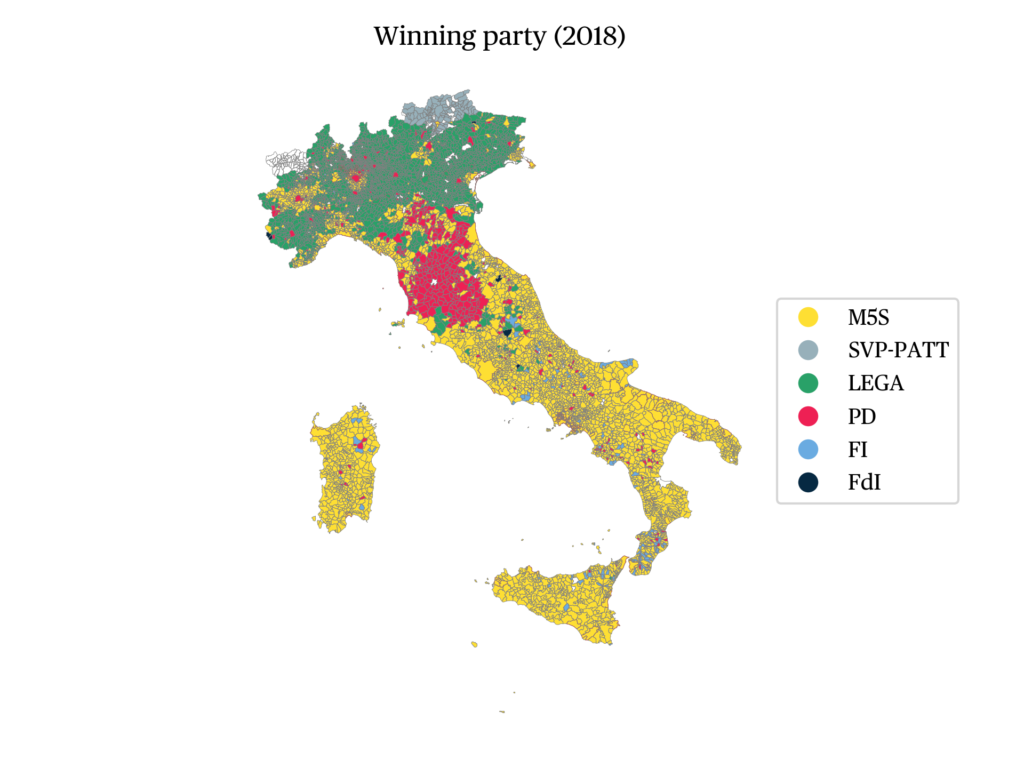

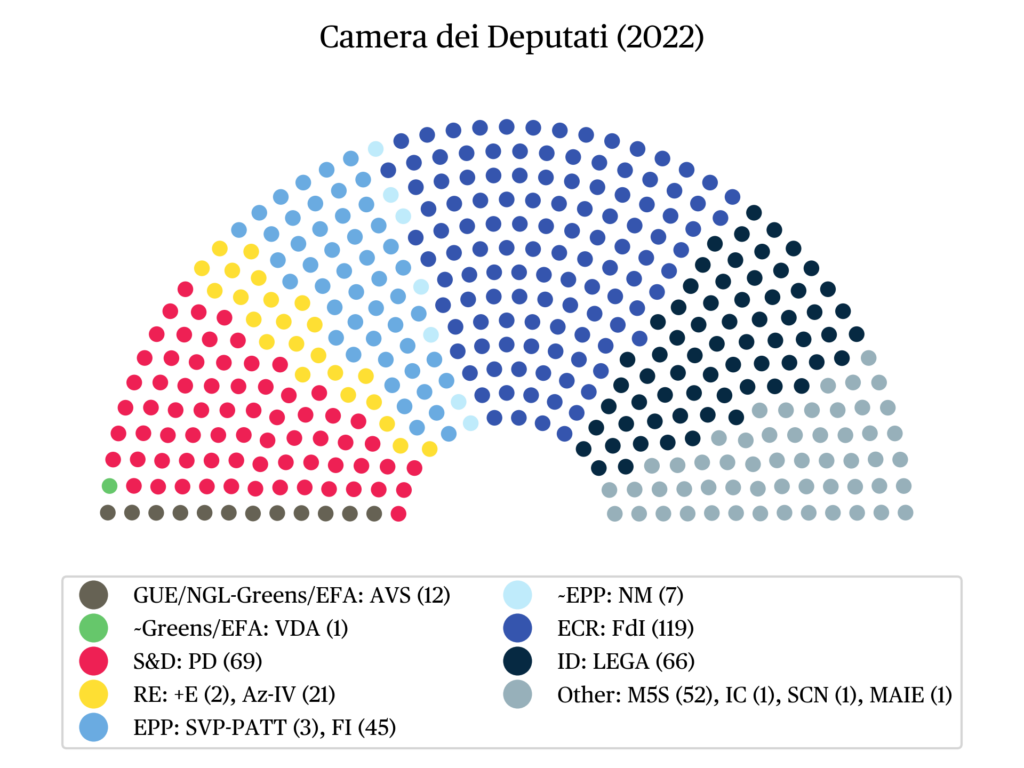

As it was the case in 2018, the election results again pointed out Italy as being divided between the North and the South, but with a clear differentiation: while the M5S was again the clear winner in the South of the country, in 2022 it won far less constituencies than in 2018 with the FdI being the clear winner almost everywhere else (see maps below; cf. Garzia 2022). The PD remained the largest party only in some of its strongholds in the so called “red-belt” in the centre of Italy. It was clear that all parties in government suffered loss and were punished by voters. In fact, and although post-election surveys are not available yet, looking at the aggregate level it is plausible that FdI attracted voters not only from the radical right, but from the entire ideological spectrum. As concerns the distribution of seats, it is interesting to note from the last figure that while elections were fought by three main coalitions, the resulting parliament is rather fragmented due to the internal fragmentation of those same coalitions. One has to notice that the referendum held in Italy in September 2020 had seen the significant reduction of the number of deputies in the lower chamber (from 630 to 400) and the upper chamber (from 315 to 200). This has made it more difficult for parties to anticipate the distortive effects of the electoral system, especially when drafting the electoral lists.

Conclusions

Given the formation of the pre-electoral coalition and the majority of seats enjoyed by the centre-right coalition, government formation was among the quickest in Italian recent electoral history. On October 21st, Giorgia Meloni has been named Italy’s first female prime minister at the head of a right-wing government. In addition, given the much stronger support received by FdI compared to its coalition partners (League and FI), the expected new Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni was able to push through many of her party’s desires in terms of cabinet positions. FdI got 9 ministries and 4 vice-ministries, while the League and FI 5 each and 5 to independents. Symbolically, Matteo Salvini (League) and Antonio Tajani (FI) were appointed as Vice-presidents of the Council of Ministers. While several key ministries such as the Interior went to non-party members, FdI retains key ministries such as Defence, Justice and EU affairs. Overall, several Ministers of Meloni’s cabinet are names long known in Italian politics, with experience in previous Berlusconi governments — a choice that highlights continuity within the right-wing coalition and is probably aimed to reassuring international observers that despite her post-fascist background she will not enact radical policies.

Looking specifically at some policy proposals, however, the practical impact of the new government on civil, political and social rights (in brief, some aspects of the quality of Italian democracy) might be large. Meloni supports a constitutional reform that, allowing for the direct election of the President of the Republic, might transform Italy from a parliamentary to a presidential republic. As concerns the economy, the government has proposed another pension reform (“quota 41”), a flat tax and a raise in the ceiling on the use of cash — provisions that could further increase public debt and encourage tax evasion. On cultural and identitarian issues, the agenda mainly revolves around restricting immigration (preventing NGO ships from disembarking migrants in Italian harbours) and safeguarding traditional family values (therefore strongly opposing LGBTQ+ communities and limiting reproductive rights). On the international scene, conversely, Meloni highlighted Atlanticist positions and toned down her past Euroscepticism, trying to appear as a legitimate and rather moderate counterpart. All in all, however, the impact of the new government will depend on the stability of the coalition itself, which at present relies on a delicate balance of power.

References

Garzia, D. (2022). The Italian parliamentary election of 2022: the populist radical right takes charge. West European Politics: 1-11.

Garzia, D., & Karremans, J. (2021). Super Mario 2: comparing the technocrat-led Monti and Draghi governments in Italy. Contemporary Italian Politics 13(1): 105-115.

Giannetti, D., Pinto, L., & Plescia, C. (2020). The first Conte government: ‘government of change’ or business as usual?. Contemporary Italian Politics 12(2): 182-199.

Newell, J. L. (2019). Italian politics: The ‘yellow-green’government one year on. Contemporary Italian Politics 11(3): 205-207.

Notes

- Italy is one of the main recipients of the funds allocated by the Recovery and Resilience Facility of the European Union, aimed at supporting member states most hit by the coronavirus pandemic. The European Commission has approved Italy’s recovery and resilience plan in July 2021, making 191.5€ billion (corresponding to 10% of the total Fund) available for the country. Meloni has, however, repeatedly claimed that she wants to re-negotiate the agreement.

- Ettore Rosato, from PD, drafted the law in 2017.

- For single lists, the electoral threshold is 3% of votes obtained at the national level or 20% of the votes obtained at the regional level valid only in the Senate. For coalitions, the electoral threshold is 10 percent of the votes obtained at the national level, provided they include at least one list that has passed one of the other thresholds. The remaining 2% of the seats are allocated based on the votes of Italians living abroad.

citer l'article

Carolina Plescia, Sofia Marini, Parliamentary election in Italy, 25 September 2022, Mar 2023, 109-113.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue