Parliamentary Election in Scotland, 6 May 2021

Fraser McMillan

Researcher, University of GlasgowIssue

Issue #1Auteurs

Fraser McMillan

21x29,7cm - 102 pages Issue #1, September 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe: December 2020 — May 2021

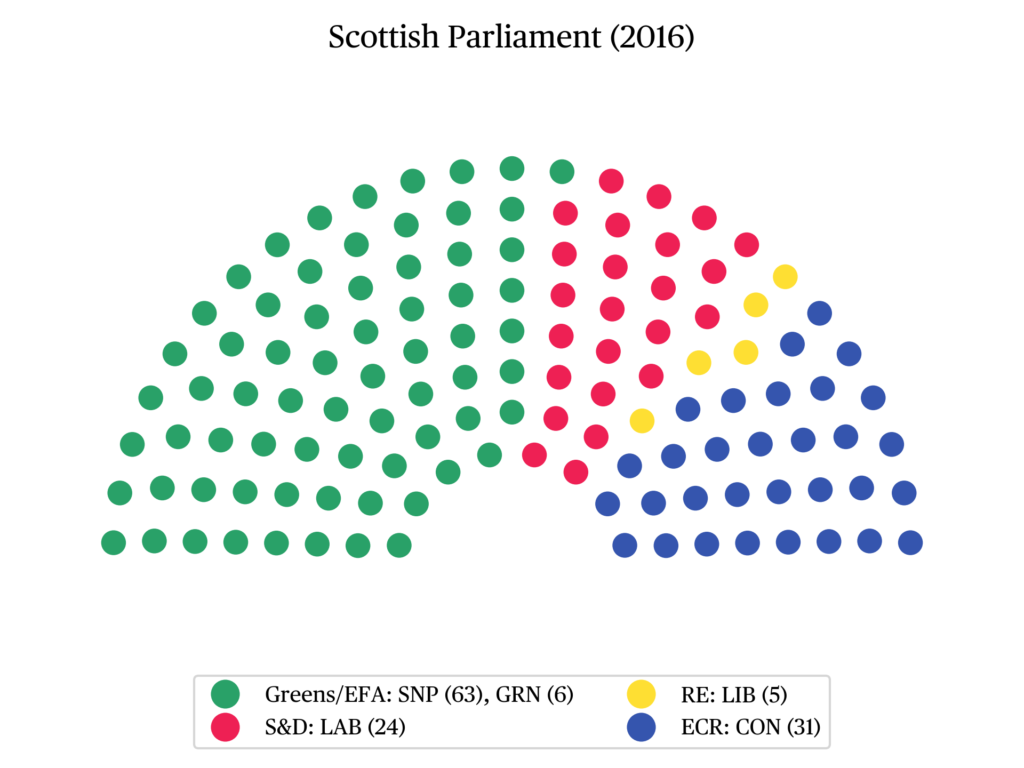

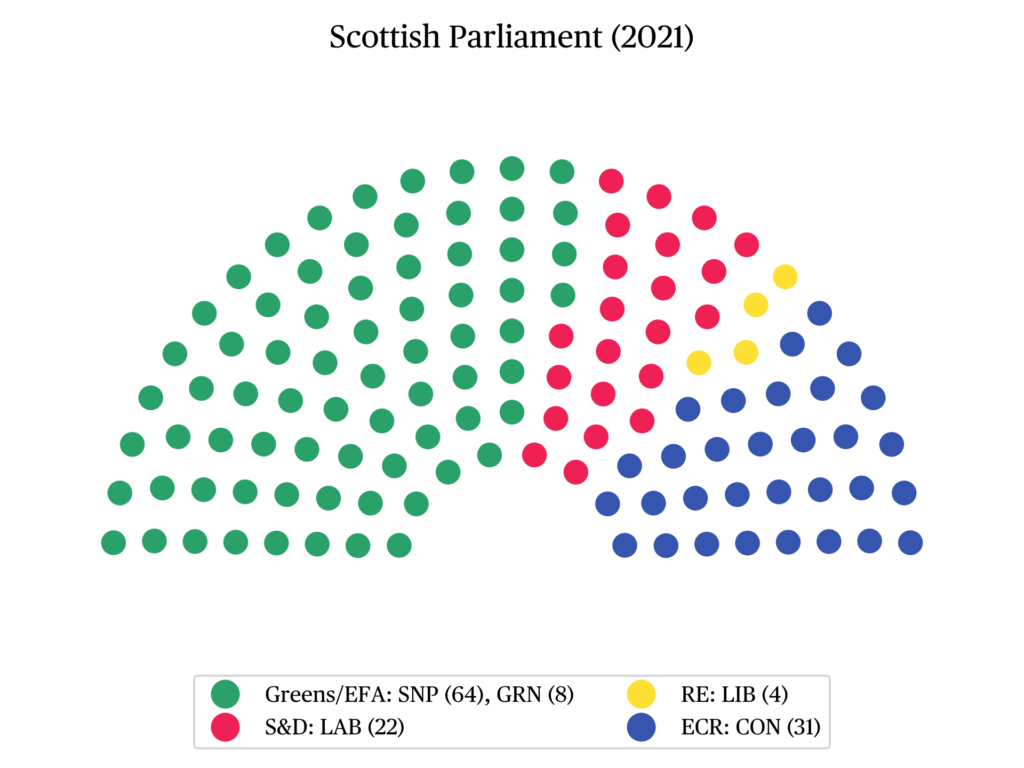

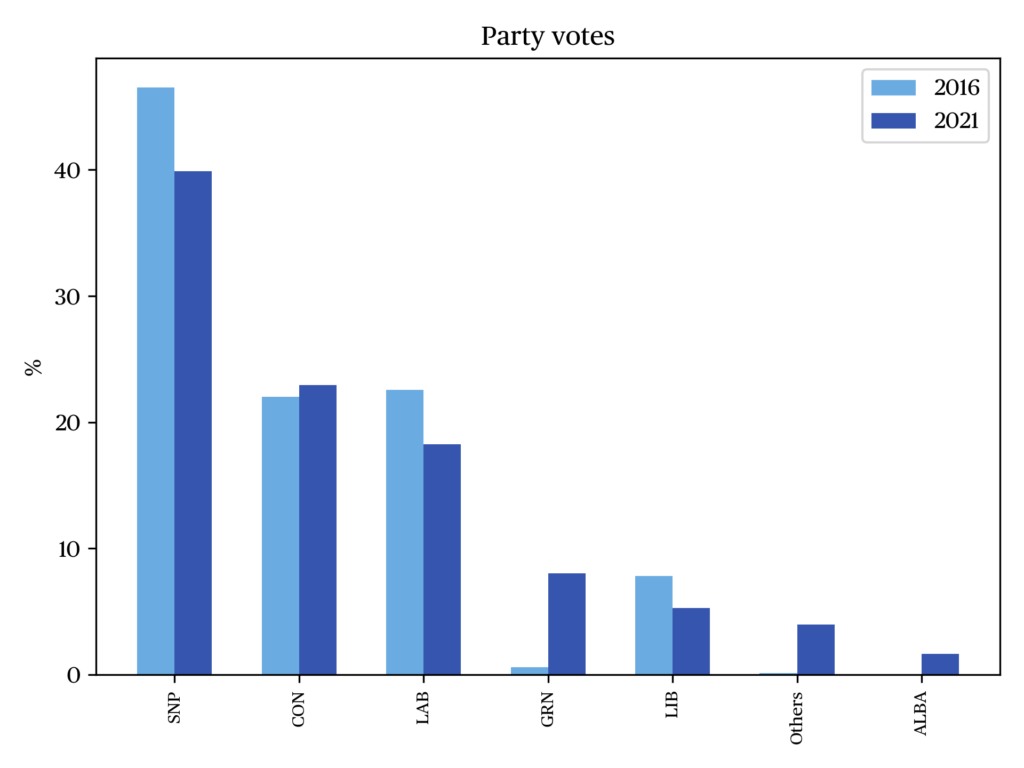

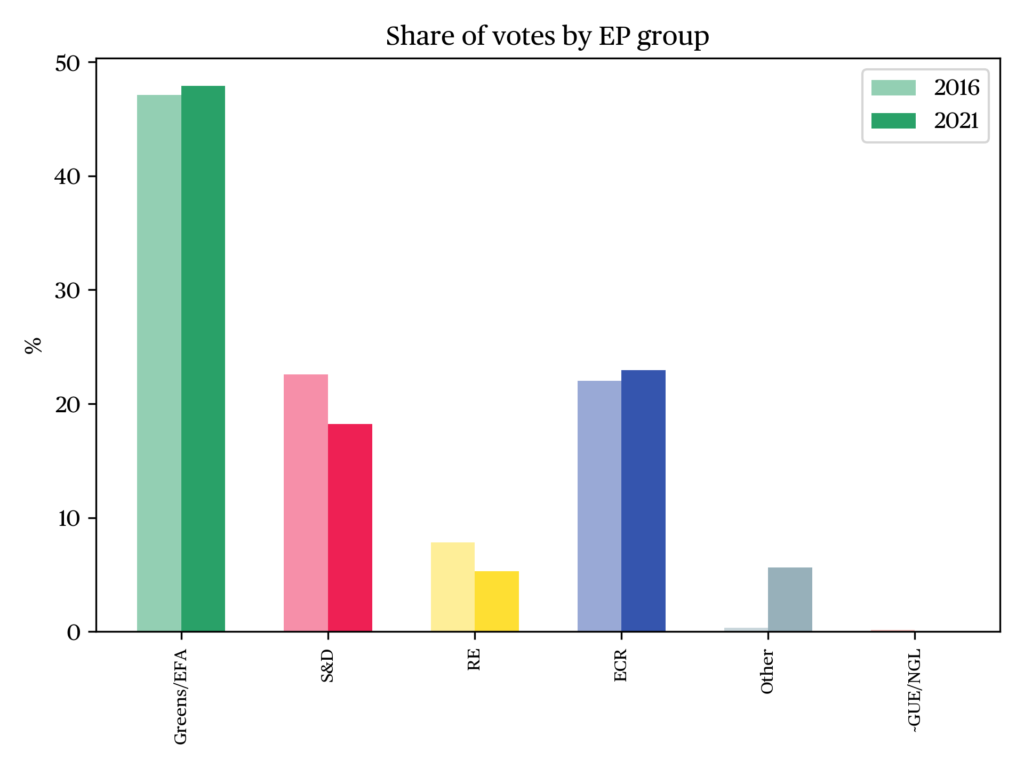

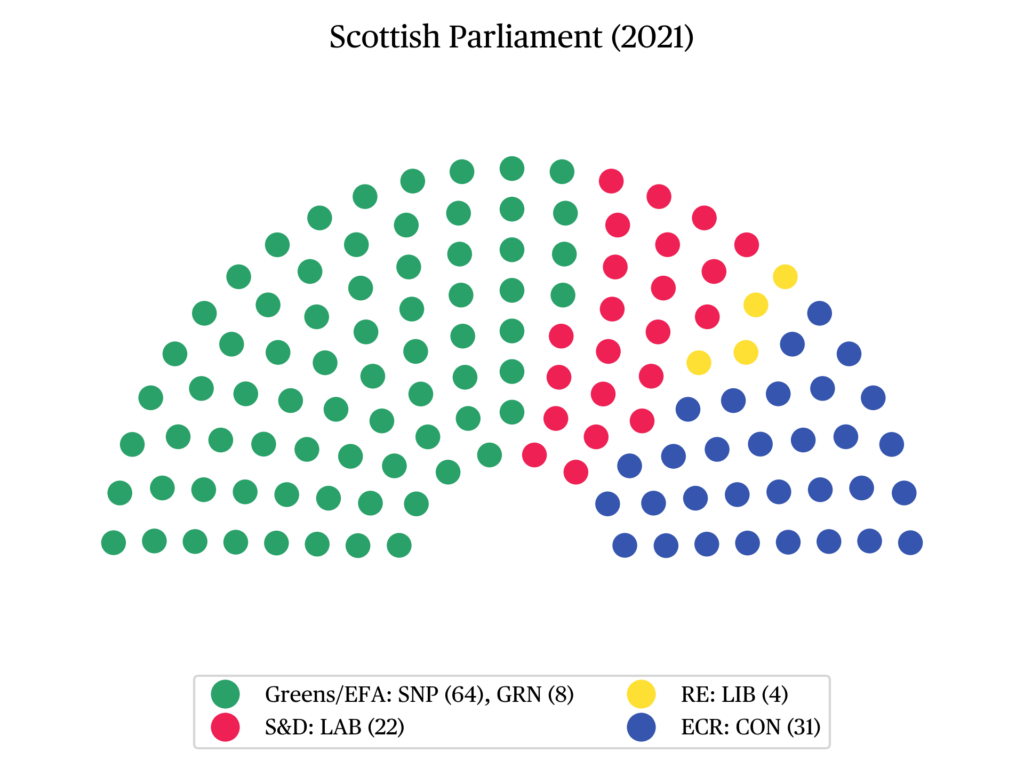

Comparing the party composition of the Scottish Parliament (Holyrood) sworn in this month to the one elected five years ago, little looks to have changed. Vote shares barely shifted versus 2016, and none of the five main parties gained or lost more than two seats in the country’s 129 Member legislature, which is elected using a mixed system combining Westminster-style single-member districts with proportional top-up party lists at the regional level. Figure a shows how similar the result was to 2016.

But the apparent aggregate stability of Scottish electoral politics masks significant shifts under the surface after five years of constitutional and social upheaval. And the result guarantees an intense intergovernmental battle over the devolved parliament’s constitutional authority to hold a referendum on leaving the United Kingdom.

If 2021 turnout is anything to go by, Scottish citizens are deeply invested in this coming clash. Voters had been widely expected to stay away from the polls given the near-total absence of traditional campaigning. Parties bombarded households with bullet-pointed pamphlets and the leaders debated on television no fewer than six times. But, with candidates unable to organise in-person events or canvass as they normally would, there were concerns that the campaign was making little impression.

Despite suggestions this could result in a sub-50% turnout, voters showed up in record numbers. Participation surged by nearly eight percentage points to 63.4%, comfortably the highest level since the parliament opened in 1999. The increased number of postal ballots and greater free time to head to the polls during lockdown may have contributed to this boost. But it’s clear that, even experiencing a largely-digital campaign amid a gradual return to post-lockdown normality, the Scottish electorate had politics on the mind.

Background

It is difficult to avoid attributing the spike in participation to the ever-present issue of Scotland’s sovereignty, even though opinion polls suggested that the COVID pandemic and recovery were far and away the public’s highest priorities. While the pro-independence Scottish National Party (SNP), in power since 2007, went into the election emphasising continuity and pandemic recovery, they also promised to hold a referendum on leaving the UK by the end of 2023. This would be the second vote on the matter, following the historic original contest in 2014. On that occasion, the Yes to independence campaign lost with a higher-than-expected 45% share having picked up significant support over the course of the campaign.

As a result, the No campaign secured only a pyrrhic victory. Scotland’s political landscape today is entirely a product of that referendum which, rather than resolving the question, let the nationalist genie out of the bottle. The plebiscite legitimised and mainstreamed the previously fringe pursuit of Scottish independence, and SNP membership swelled several times over in the days and weeks afterward. The party went on to win 56 of Scotland’s 59 Westminster seats at the 2015 general election — held, of course, using a pure First-Past-the-Post system —, an increase of 50 which reversed Labour’s stranglehold on the country overnight.

The 2016 Scottish Parliament elections saw the Scottish electorate realign according to constitutional preferences: just one in ten SNP voters was opposed to independence, versus one in three in 2011. But an influx of pro-independence voters and constitutional convers helped the SNP offset these losses to win their third Holyrood victory in a row. That said, the independence issue might have faded into the background for some time had the UK not voted to leave the European Union in yet another constitutional referendum just weeks later. While the UK as a whole chose Brexit, it was opposed by nearly two thirds of Scottish voters. This immediately reignited the independence argument, not least because the SNP manifesto contained a pledge leaving the door open to another referendum in the event of a “material change of circumstances… such as Scotland being taken out of the EU against our will”.

While Brexit complicated the practicalities of Scottish independence, it undermined a key plank of the pro-union campaign’s 2014 platform and reemphasised the “democratic deficit” that Scottish devolution was supposed to resolve – that is, the country voting for one outcome and getting another. It also, thanks to the SNP manifesto, created the pretext for another bite at the independence cherry. The 2016-2021 SNP minority administration, with the wildly popular Nicola Sturgeon at its head as First Minister (she attained a net +50 approval rating at some points in 2020), requested the legal authority to hold a second referendum on multiple occasions. Each time, however, they but was were repeatedly rebuffed by successive Conservative Prime Ministers arguing that the timing was not appropriate.

Context

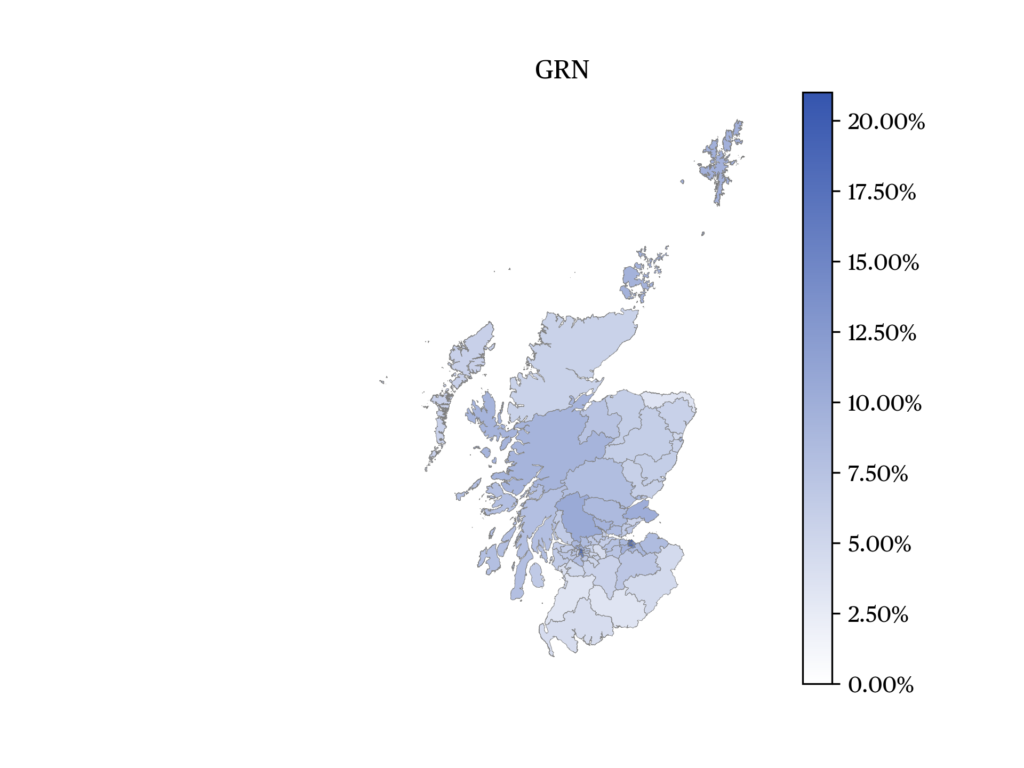

With polls throughout 2020 and early 2021 suggesting that the pro-independence side had gained a slight edge in public opinion, the SNP portrayed the 2021 election as an opportunity to obtain a renewed mandate to put the question before voters and send a message to Westminster. The Scottish Greens, who had provided the votes to pass the SNP’s budgets since 2016, made a similar pledge. Both parties also support Scotland rejoining the European Union as an independent state — it is no accident that most of the movement in independence polling has been down to risk averse Remain voters to whom the UK no longer appears the safe bet. Demographically, these shifts have erased gender differences on the constitutional question and weakened the link between socioeconomic prosperity and support for the union.

In the 2021 campaign the anti-independence parties – the Conservatives, Labour and the Liberal Democrats – all pledged to oppose a second referendum with varying degrees of vehemence. Otherwise, the parties disagreed on little of substance — Scotland’s elite policy consensus is well to the left of centre. The international trend towards ambitious spending and future-proofing in the wake of the pandemic has narrowed whatever distance there was between the SNP, Scottish Labour and the Scottish Greens.. And while nobody would describe them as being on the left, even the Scottish Conservatives ran on a high-spending, socially liberal platform. Much of the top-level campaign focused on the coronavirus recovery and the SNP’s performance in government rather than the prospect of a referendum. Safe in the knowledge that most pro-independence voters were already likely in their camp, the SNP primarily emphasised Sturgeon’s pandemic handling and experienced leadership rather than the constitution.

The only major surprise of the campaign came with the late entry of a new pro-independence political party led by disgraced former SNP First Minister Alex Salmond. Salmond had served as Scotland’s First Minister between 2007 and 2014 and was Sturgeon’s friend, mentor and boss for decades, but the pair became estranged after multiple sexual harassment and assault complaints against him came to light in 2018. Salmond won a legal challenge against the Scottish Government for procedural failings and was acquitted of criminal charges in 2020, arguing that past “inappropriate” conduct did not rise to criminality.

This complicated scandal reached its political apex weeks before the 2021 election, when both Salmond and Sturgeon appeared in front of a parliamentary committee investigating the complaints process. Salmond alleged an implausible conspiracy between civil servants and senior SNP figures to take him down, while Sturgeon claimed she had responded appropriately and sought to emphasise the personal difficulty of the situation. Opposition politicians had hoped the case would damage Sturgeon or even result in her resignation, but she was cleared of breaching the Ministerial Code by an independent government legal advisor shortly after her committee appearance. The affair generated a great deal of heat, but very little light.

Salmond was not ready to leave the stage, however, and he attempted to return to the political scene as leader of the new Alba Party in the run-up to the election. They ran only on the proportional regional ballot and adopted a more aggressive pro-independence platform, providing a home for elements of the movement who simultaneously oppose the SNP’s social liberalism and cautious, pragmatic approach to securing a second independence referendum.

Results

If the first post-referendum Scottish election suggested that the country’s electoral politics had reoriented around the constitutional question, the 2021 contest confirmed beyond all doubt that the nation is deeply polarised on the matter of its future relationship with the rest of the UK. Voters on both sides of the divide behaved more strategically this time around, attempting to exploit the voting system to maximise representation of their constitutional preference. For unionists, this meant consolidation, as strategic voting increased in constituencies all over the country. For the nationalists, it meant modest fragmentation, with the Scottish Greens gaining further ground in the regional ballot. The results from each ballot are shown in figures b et c.

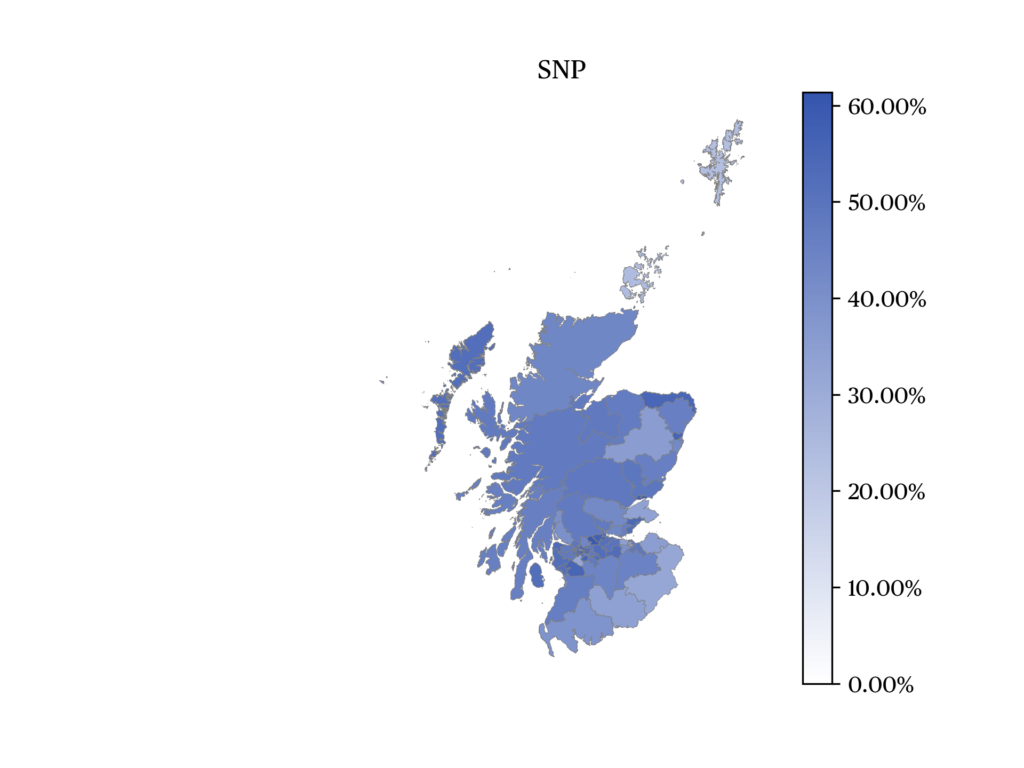

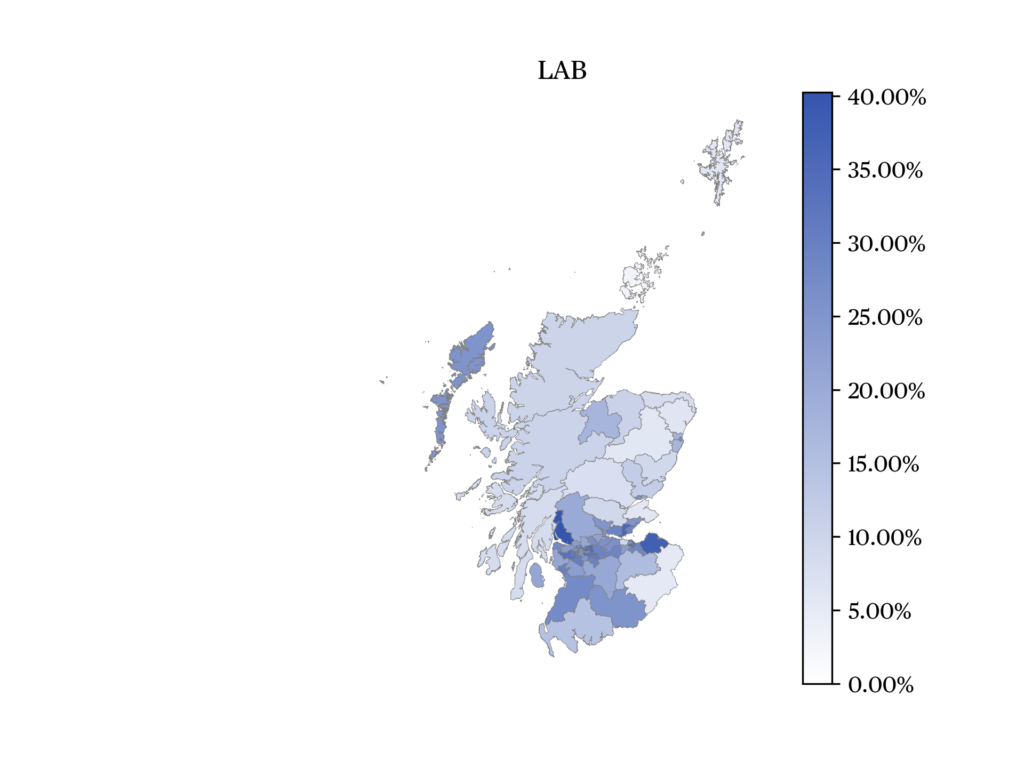

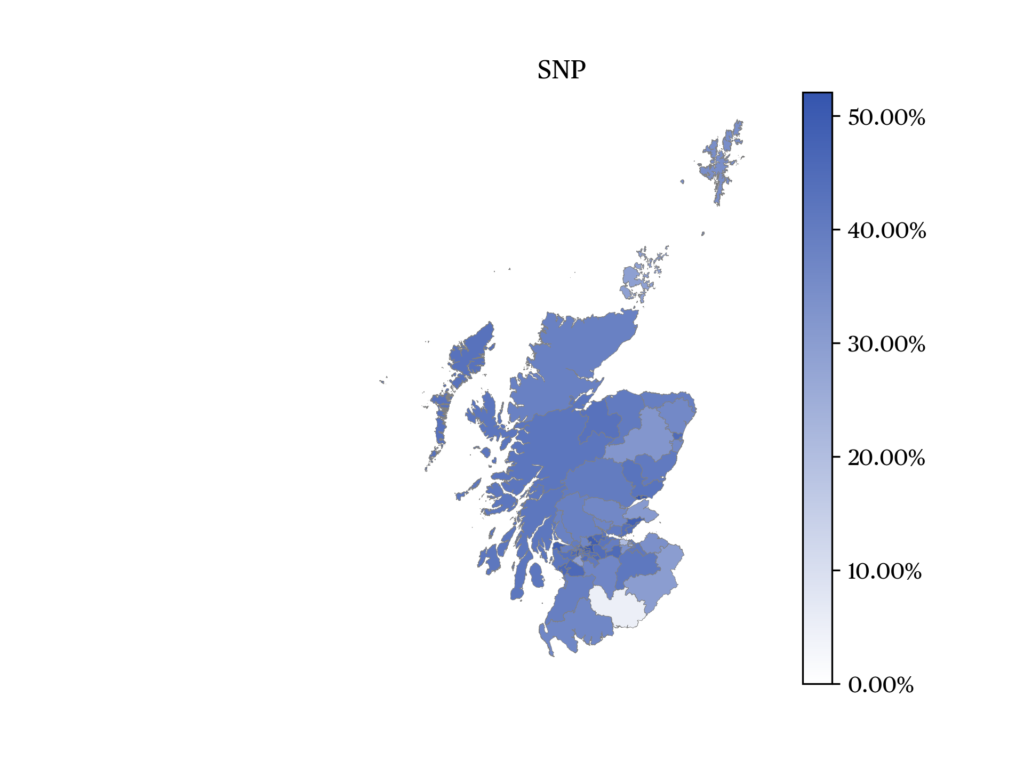

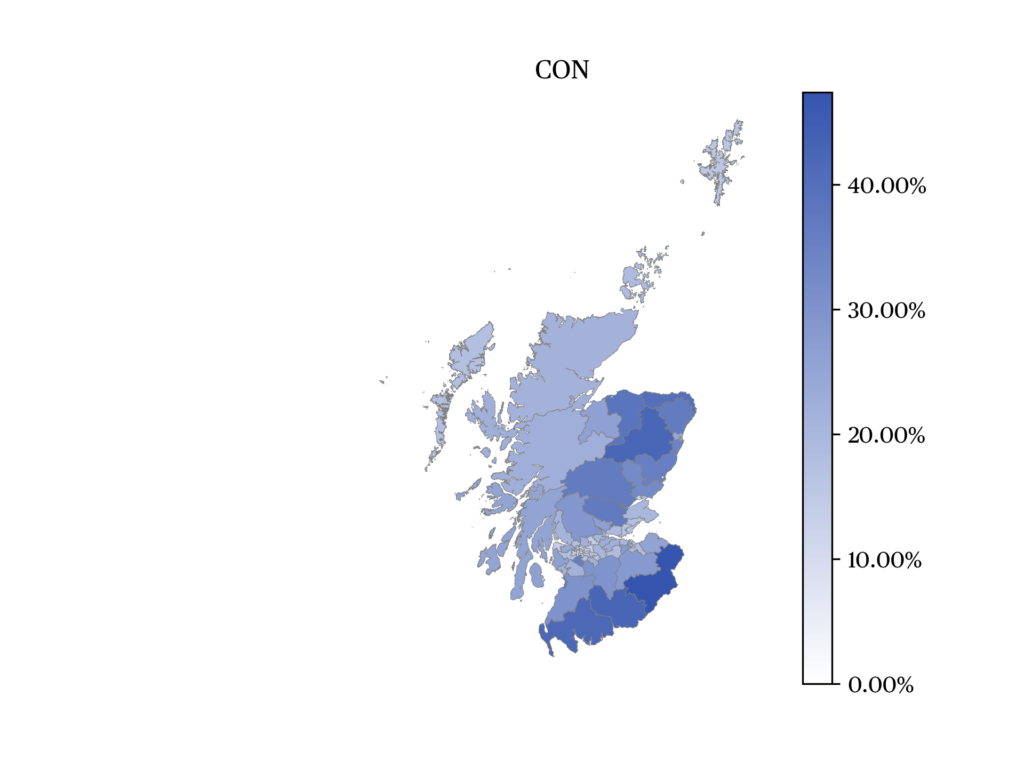

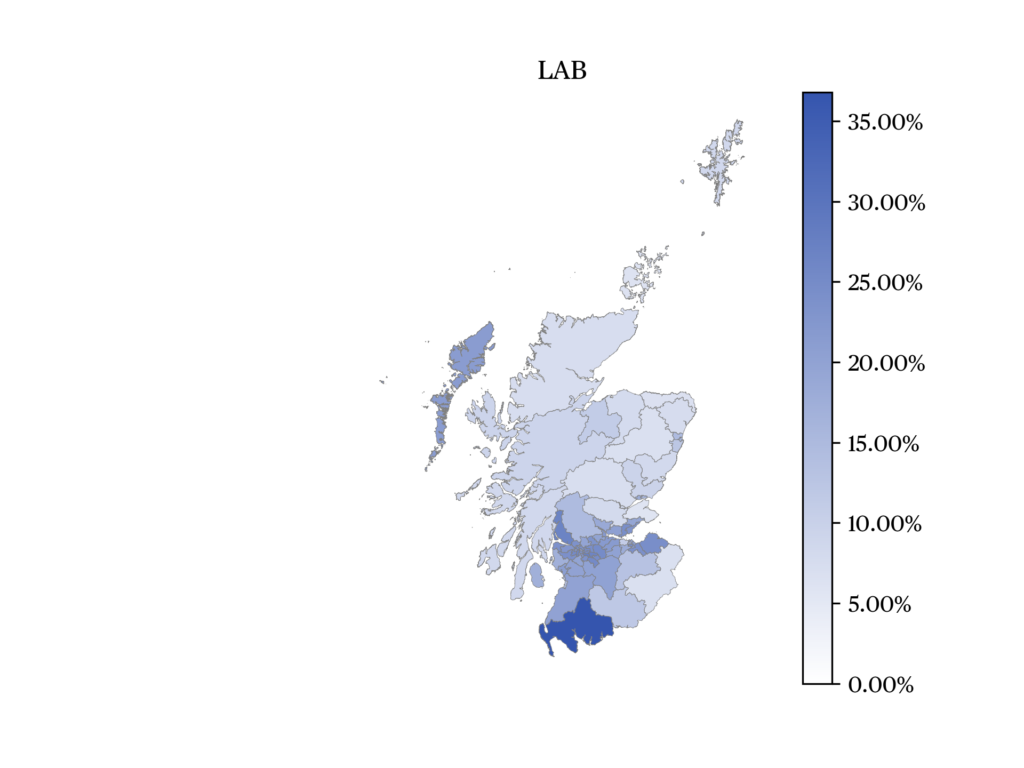

The story of the 2021 election is therefore one of deckchairs being rearranged within each constitutional camp rather than much movement between them. That’s why the outcome fell in the same range as 2016 despite the twin sociopolitical earthquakes of Brexit and COVID. Overall vote shares changed little, with the SNP up 1.2% to 47.7% in the constituencies but down a similar amount to 40.3% on the regional ballot. The Conservatives remained static in the constituencies (losing 0.1%) and gained slightly on the list, landing on 21.9% and 23.5% respectively, while Labour dropped a point or so on each ballot to finish third again on 21.6% and 17.9%.

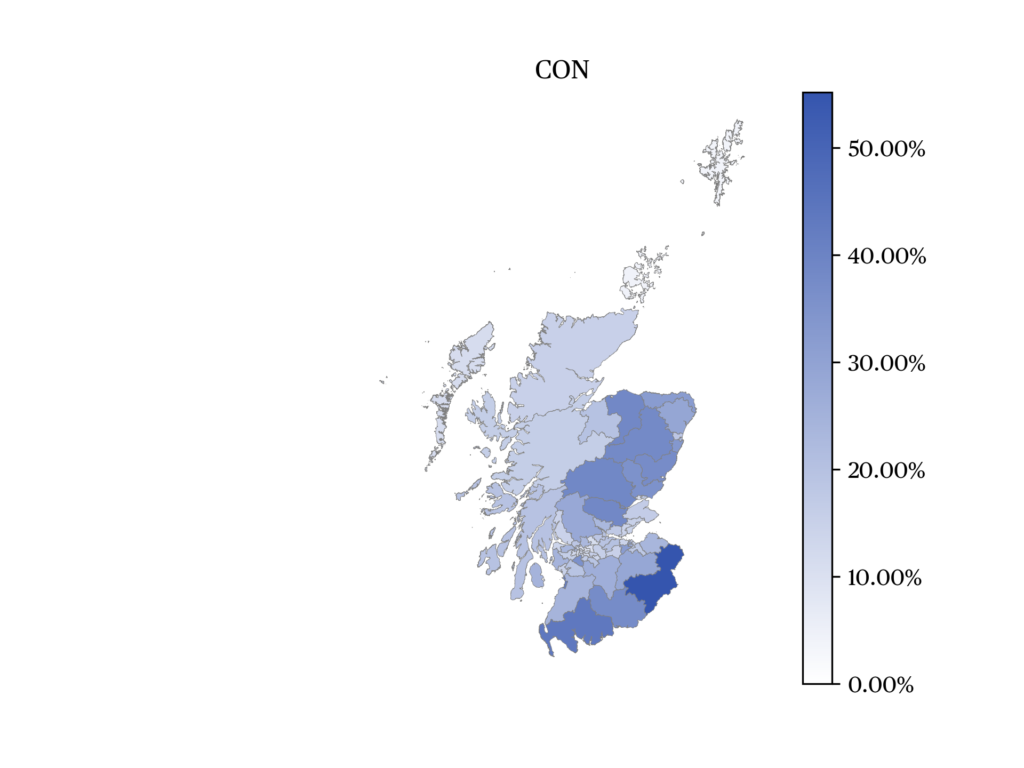

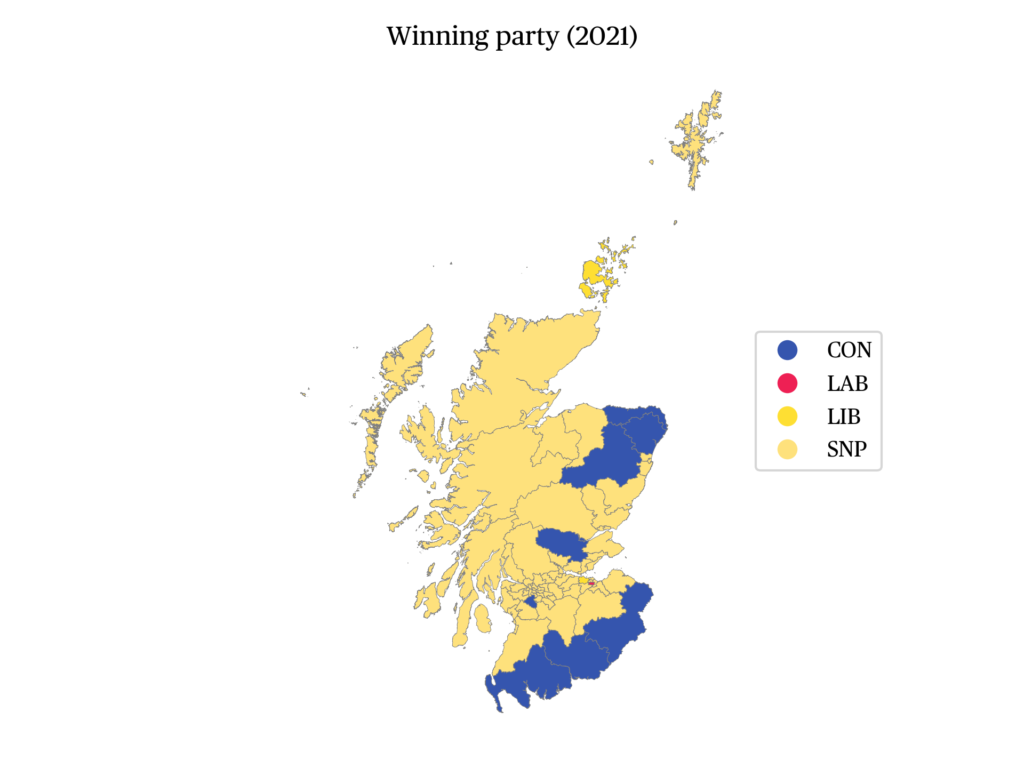

While the aggregate results appear very stable, they mask a some amount of churn due to local and regional divergences. The SNP consolidated its dominant position in First Past the Post constituencies, gaining three seats to take its total to 62 of an available 73. However, the party wins so many constituencies it is virtually impossible for them to take PR top-up seats in most of Scotland. The constituency gains and reduced list vote share resulted in the loss of two out of four proportionally allocated seats, both in the South of Scotland region which contains the strongly anti-independence Borders area. This is visible in Figure d. This left the SNP with a net gain of a single seat vs. 2016, taking their total to 64 – just one short a parliamentary majority.

Given the hurdles presented by the electoral system, this would be considered a remarkable achievement in any other circumstance. However, commentators had talked up the prospects of an SNP majority before the election, to the point that this became the central question about the outcome. Pro-union lawmakers and commentators seized on the SNP’s single-seat deficit in the election’s aftermath to argue that this undermines the Scottish Government’s moral authority to pursue a second referendum. These claims, of course, apply the majoritarian standards of First-Past-the-Post to a semi-proportional electoral system in which nearly half of seats are drawn from multi-member districts, and illustrate how deeply ingrained this “Westminster mindset” is in Scottish political culture.

For their part, unionist party vote shares remained virtually static overall. However, there was significant geographical variation. Unionist incumbents increased their vote share in 8 of 13 constituency seats won by these parties in 2016, of which they ultimately retained 10. And in the large number of constituency seats won by the SNP in 2016, anti-independence voters flocked to the nearest challenger. The 2021 election demonstrated just how robust the pro-union vote in Scotland is, a fact which is often forgotten in light of rising support for independence.

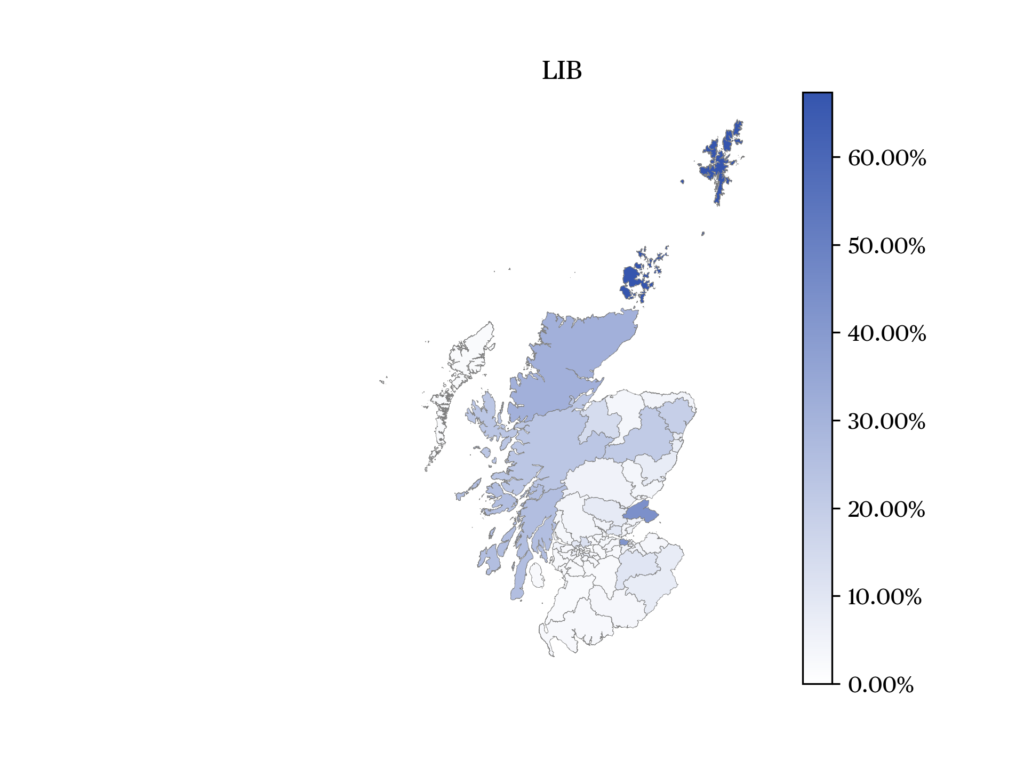

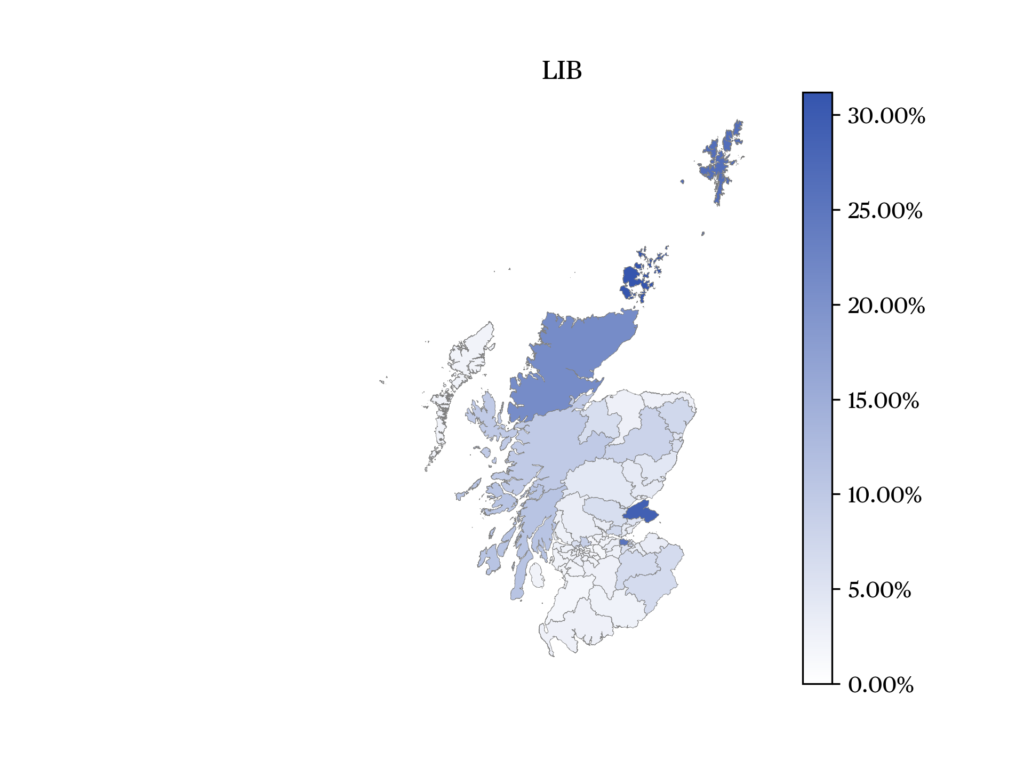

These dynamics especially benefitted the Conservatives, who gained an average of around three percentage points in seats where they finished runner-up in 2016. The party’s 2021 gains demonstrate a linear association with the share of voters who chose Leave in the EU referendum. Other anti-independence seats with stronger ‘Remain’ leanings gravitated towards Labour and the Lib Dems, depending on who was best placed to beat or challenge the SNP. As a result, there are very few “three-way marginal” seats remaining – the overwhelming majority of constituencies are straight fights between the SNP and the best-placed unionist challenger, and who that is largely depends upon the proportion of pro-Brexit voters in the seat.

While the overall vote share for pro-union parties slightly declined, tactical voting ensured that its efficiency increased. This strategy undoubtedly deprived the SNP of a majority, with target constituencies such as Dumbarton, Eastwood and Aberdeenshire West remaining just outside the nationalists’ grasp even as they meaningfully increased their share of the vote in each locality.

However, this outcome is unlikely to frustrate the pursuit of a second independence referendum. An increased number of SNP constituency voters gave their regional vote to a different nationalist party on the list – but it was the Scottish Greens, rather than Alba, who capitalised on this. Alba secured 1.6% of overall list votes and didn’t come close to winning a seat in any region. The Greens, meanwhile, captured 8.1% of the proportional vote to achieve their best ever result of 8 seats, cementing their status as the fourth-largest party and bringing the total number of pro-independence MSPs to a record 72. There may prove to be room in the party system for a more aggressively nationalist project which promises heightened confrontation with Westminster, but it is unlikely to be one led by a figure as unpopular as Salmond.

Finally, the election also produced the most diverse Scottish Parliament yet elected. The legislature is now close to gender-balanced, with 45% women MSPs. This contingent includes the parliament’s first full-time wheelchair user and its first two minority ethnic women. Six minority ethnic representatives were elected in total, all of whom are from a South Asian background. While there remains scope for progress, these advances were welcomed across the political spectrum.

What’s Next?

The result leaves the parties in much the same place as they were before the election, albeit with a slightly tighter nationalist grip on the legislature as a whole. The SNP will continue as a minority administration buoyed by Scottish Green support — this time, perhaps, backed by a more formal cooperation agreement — and they will renew their push for another referendum once the pandemic fades.

The fundamental problem for unionists in Scotland remains their electoral fragmentation. The SNP’s position is envious, as the party virtually monopolises the constituency vote of independence supporters and can rely on an ever-enlarging Green contingent to provide backup on essential budget votes and constitutional matters. The traditional Westminster parties meanwhile — among whom there is a great deal of historic animosity, as well as irreconcilable policy differences — are forced to split the other half of the electorate three ways.

This places the anti-independence cause in a structurally perilous position. The Scottish Parliament has had a continuous pro-independence majority since 2011, and that is highly unlikely to change until the issue is resolved one way or the other. The country seems destined to hold another independence referendum at some point, and age patterns in attitudes to independence suggest that time is not on their side: independence would comfortably carry the working age population in another referendum, and Yes beats No by as much as 70%/30% among younger cohorts.

With an unpopular UK government likely to spend the next few years frustrating the Scottish Parliament, nationalists also have an opportunity to rebuild the dubious economic case for independence and consolidate support for their cause. The politics of Brexit may have convinced some No voters to switch sides, but its practicalities could push them back in the other direction. While Sturgeon must walk a strategic tightrope — and will face pressure to hold a Catalonia-style “advisory” referendum in the event that a legally-binding contest proves impossible — she is playing the long-game and understands that the surest route out of the United Kingdom is one supported by a convincing majority of Scots in a referendum with widespread legitimacy. The wider Yes movement is probably less patient than this, and that may eventually cause real problems for the First Minister.

The likeliest way to build that majority, for now, is to exploit the “undemocratic” recalcitrance of Boris Johnson’s government on the matter of a referendum itself. While the strong unionist showing at the 2021 election showed that Scottish independence is far from inevitable, this feedback loop may ultimately prove the undoing of Great Britain as a political whole after more than three centuries of shared sovereignty. The Prime Minister will be all too happy to play along, knowing that a Gaullistic “Non” to Scotland is in his short-term interest even if it is a danger to the union’s long-term future. The longer the constitutional-legal confrontation between Scotland’s two, increasingly-estranged governments continues, the more likely it seems that public opinion will swing behind independence.

The Data

citer l'article

Fraser McMillan, Parliamentary Election in Scotland, 6 May 2021, Sep 2021, 86-91.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue