Parliamentary election in Spain, 23 July 2023

Santiago Pérez-Nievas

Professor at the Universidad Autónoma de MadridIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Santiago Pérez-Nievas

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

Introduction

On May 29, 2023, the President of the Spanish Government and leader of the PSOE, Pedro Sánchez, announced by surprise the call for general elections (Congress of Deputies and Senate) for July 23 of that same year, six months earlier than anticipated. Sánchez’s strategic shift in announcing this advance was in response to the results of the local and regional elections of the previous day, in which the conservative Popular Party (PP) managed to gain access to a majority of mayors’ offices and regional governments, although in many cases necessarily through government pacts with the radical right-wing party, Vox.

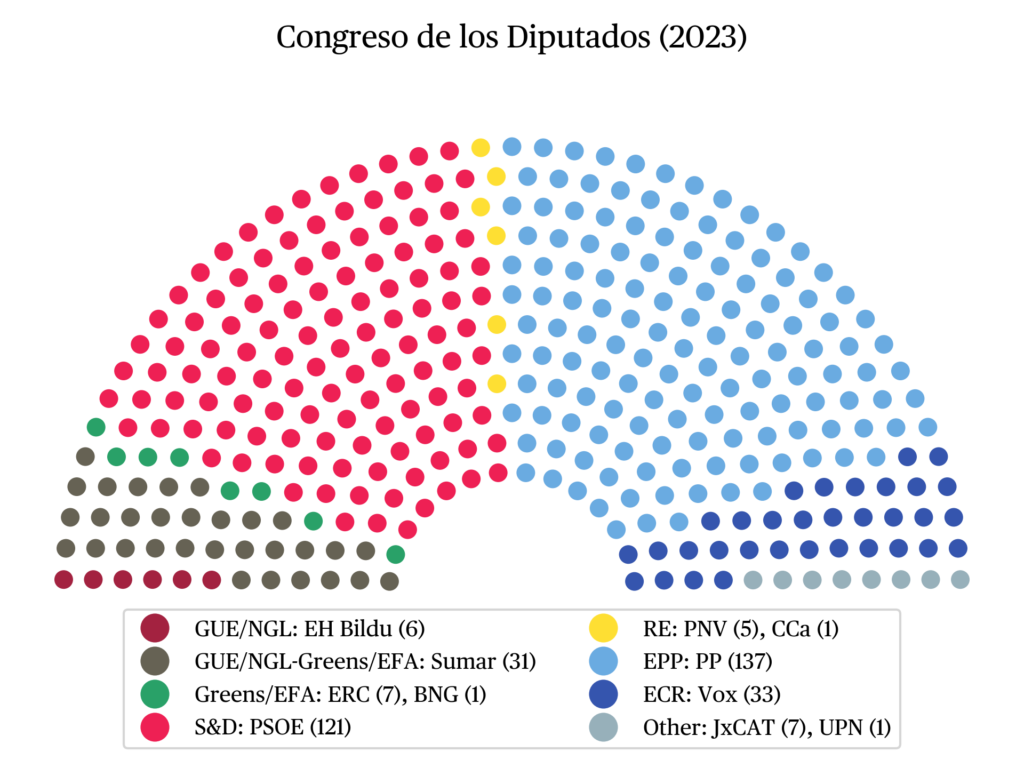

Two months later, in the July 23 elections, the PP won the elections, although by a narrower margin with respect to the PSOE than most pre-electoral surveys had predicted. The PP won 137 deputies in Congress while the PSOE obtained 121, far in both cases from the absolute majority of 176 seats (out of a total of 350 in all). The left-wing coalition Sumar, in which the government coalition partner Unidas Podemos participated, won 31 seats, while Vox obtained 33. The remaining 28 seats in the chamber went to a set of 7 nationalist or regionalist parties of diverse ideologies. From election night itself it seemed unlikely that the right-wing bloc could find sufficient support, although the leader of the PP, Alberto Núñez Feijóo, presented his candidacy in Congress — which was rejected — at the end of September. To avoid a repeat election, the only alternative was a parliamentary coalition of the PSOE with five other parties (including Sumar), an agreement that seemed particularly difficult to reach with the Catalan nationalists of Junts Per Catalunya (JxCat), whose leader, Carles Puigdemont, is still on the run from Spanish justice. In November, the PSOE and JxCat reached an agreement whereby the latter committed to the investiture of Sánchez in exchange for the approval of an Amnesty Law for those indicted for the organization of the illegal referendum in Catalonia in October 2017. A week later Sánchez was invested president of a coalition government (PSOE-Sumar), amid a climate of strong protests against the amnesty.

The PP won a resounding victory in the Senate, which follows a majority electoral system and not a proportional one as in the Congress. Although the Senate does not play a role in the formation of the government, the PP’s predominance in the upper chamber may have implications for the development of the legislature.

Background and Context

Sánchez’s first coalition government (2020-2023) developed in a climate of strong and growing political polarization (Torcal and Comellas, 2022). The two-party system that had characterized Spain in previous decades gave way since 2015 to a crisis of the party system, with the rise and disappearance of a center-right party (Ciudadanos); the rise, crisis and reconfiguration of a coalition of radical left-wing parties (first Unidas Podemos, and more recently Sumar), and the irruption since 2019 of a radical right-wing party (Vox). After the formation in January 2020 of the first left-wing coalition government, the system has been reconfigured into two blocs: with PP + Vox, as the right-wing bloc, and PSOE + Unidas Podemos/Sumar, as the left-wing bloc. The two blocs compete not only on the right-left axis, but also on the center-periphery or nationalist axis (Simón, 2020). In general terms, the right is more centralist and suspicious of peripheral identities, especially Vox, rooted in a nativist and exclusionary Spanish nationalism. In contrast, the PSOE and radical left coalitions have tended to be more sympathetic to nationalist parties, and specifically more supportive of dialogued solutions around the 2017 Catalan crisis. This overlapping of the left-right axis and the nationalist axis intensified after Sánchez’s election in 2018 by constructive censure motion with the support of nationalist parties, including EH-Bildu, heir to the party linked to the terrorist group ETA, as well as the Catalan parties that in 2017 promoted the illegal referendum in Catalonia: Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC) and JxCat. After the 2019 elections, Sánchez was elected president of the first coalition government, with the positive vote or tacit abstention of most of these parties, except JxCat. In addition, the nationalist parties have collaborated in the approval of budgets and other important laws during the last legislature.

The first half of the last legislature (2020-2023) was marked by the COVID-19 pandemic, forcing the new government to prioritize legislative initiatives to counteract the effects of the health crisis and the subsequent economic crisis. During this first period, in the social and economic sphere, it is worth highlighting the Temporary Employment Regulation Expedients (ERTEs) which, in essence, involved the government subsidizing part of the workers’ salaries. The success of the ERTEs reinforced the ascendancy of Yolanda Diaz as a strong member of the government by the minority partner Unidas Podemos. Still during the pandemic the government also approved the Minimum Living Income (IMV), guaranteeing a minimum subsidy to anyone legally resident in Spain. Despite the criticisms raised by the implementation of the IMV, the coalition government made these social measures an electoral claim, in contrast to the austerity policies implemented by the PP during the previous economic crisis. Later on, the government also managed to approve the labor reform — one of its star promises at the beginning of the legislature — with the aim of reducing the high rate of temporary employment in the Spanish labor market. Despite a difficult procedure, the reform demonstrated the government’s capacity for social concertation (reaching agreements with unions and employers) and was, in general, well received by the public. Despite the failure in other areas, such as the housing law, at the end of the legislature the government offered a good balance on the economic and social front, with good data on unemployment and economic growth, as well as lower inflation levels than those of its European neighbors.

On the other hand, the government had more problems on other fronts. In particular, the two laws promoted from the Ministry of Equality by Irene Montero (of the minority partner Unidas Podemos) opened multiple conflicts between the two partners. In the first place, the “Ley Trans”, which aroused the open opposition of prominent PSOE leaders who disagreed with the “gender self-determination” that the new law protected. The conflict was even greater in the “solo el sí es sí” law passed in April 2022 to unify in a single criminal offense the crimes of sexual abuse and assault. The law ended up having the opposite effect of what was sought, cutting the sentences of more than a thousand convicted of sexual assault, to which Montero responded by accusing the judges of being “conservative and sexist” for their interpretation in the implementation of the law, opening a front of conflict between the Government and the Judiciary. The crisis was resolved with an agreement between PSOE and PP who approved a new law to replace the previous one, but the conflict contributed to offer a chaotic image of the government just at the end of the legislature. In the background of these conflicts was also the dispute between PSOE and Unidas Podemos for the leadership of the feminist movement, a division also reflected in the street during the 8-M mobilizations.

The coalition government also took important decisions regarding the 2017 Catalan crisis, approving nine pardons to release Catalan politicians convicted for the organization of the illegal referendum, although the disqualification from holding public office was maintained. In December 2022, and in accordance with the previous agreement set with the ERC nationalists, the crime of sedition (which had been the basis for the convictions) was repealed, replacing it with the crime of public disorder and lowering the maximum penalties. These measures were strongly criticized not only by the right-wing parties but also by many judges, and even by some regional leaders of the PSOE.

Regarding the broader political context, there were different changes, both in the political offer and within the parties. First, the center-liberal party, Ciudadanos (C’s), disappeared, failing to recover after its sharp electoral fall in 2019, leaving more than 1.5 million votes available for the July 2023 elections, which were expected to go to the PP.

The PP also had relevant crises and changes between 2019 and 2023. The legislature began under the leadership of Pablo Casado who ended up resigning in 2022 as a result of a confrontation with Isabel Díaz Ayuso — president of the Community of Madrid, also from the PP — which originated an unprecedented crisis within the party. The internal cohesion of the PP during this period was strained between a more moderate and centrist strategy, and a more exalted and radical one that tries to compete with Vox on its own ground, the latter strategy of which Díaz Ayuso is its best representative. After Casado’s resignation, the leadership crisis was resolved in favor of Núñez Feijóo, until then president of the region of Galicia — a region in the northwest of Spain and one of the main electoral strongholds of the PP —, a politician with a moderate profile until then.

The strategic dilemmas for the PP due to competition from Vox on its right flank were present throughout the legislature, especially at the regional level. After the Castilla-León elections in February 2022, the PP formed a coalition government with Vox for the first time. On the contrary, in the regional elections of Madrid (early May 2021) and Andalusia (June 2022) the PP managed to avoid the entry of Vox in the governments, although following very different strategies: while in Madrid, the PP of Díaz Ayuso gathered a majority of the right-wing vote through very aggressive campaigns in a national key, in Andalusia, on the contrary, the regional PP successfully followed a more moderate strategy appealing to the more centrist vote of the PSOE with which to obtain a sufficient majority and avoid dependence on Vox. After the change in the national leadership, Feijóo and Díaz Ayuso came to embody these different options, with tensions often aired in the media, although the strategy and discourse of the new national leader became more aggressive as the general elections of July 2023 approached.

The last significant change before the elections took place on the left of the PSOE. In the final phase of the legislature, Díaz consolidated her leadership within UP, although in increasingly open conflict with Montero and the more radical sectors of Podemos. The early elections took this space by surprise (possibly one of Sánchez’s motivations for bringing them forward) forcing the two sectors to reach an agreement on a single list (Sumar) that included several Podemos leaders in relevant positions but excluded Montero herself.

On May 28, local and regional elections were held (in 12 of the 17 Autonomous Communities). In the local elections, the PP won by 800,000 votes over the PSOE, winning six of the eight large capitals (Madrid, Valencia, Zaragoza, Seville, Malaga, Murcia). In the regional elections, the PSOE lost in eight of the ten regions in which it led or participated in the regional government; but in several of them (Valencia, Extremadura, Murcia) the PP could only access the government with Vox as a coalition partner. Possibly the main factor that influenced Sánchez in deciding to bring forward the elections was the calculation that the campaign would coincide with the entry of Vox into these governments (also in many municipalities) thus achieving a greater mobilization of left-wing voters, many of whom had stayed at home in the May elections.

Campaign

The slogans chosen by the main parties during the campaign reflected their main objectives. The PSOE slogan “Spain is moving forward” sought to establish a clear dichotomy between the modernity of its policies and those of the extreme right, insisting on the idea that voting for the PP implied choosing the second option, since the conservatives would depend on Vox to form a government. The PP’s slogan “It’s time” proposed a necessary change after a legislature that the party presented as chaotic, due to the divisions and confrontations between the coalition partners, and the government’s dependence on the pro-independence parties. Vox’s program “What matters” placed great emphasis on recentralization and the dismantling of the autonomous state, as well as the repeal of the gender policies implemented during the last decade.

Especially in the initial phase of the campaign, Sánchez had an intensive involvement participating in multiple interviews in media of very different sign. There were two televised debates. In the first debate on July 10 between Sánchez and Feijóo, organized by the private corporation Atresmedia, Feijóo was the winner according to most of the commentators (Jabois, 2023). For the second debate on July 19, RTVE summoned the four main candidates, but Feijóo declined the invitation arguing the lack of neutrality of public television. This second debate, which was attended by the other three candidates, was followed by four million viewers (almost two million less than the first one) but, in any case, it served to stage the PSOE’s message that the alternative to the left-wing coalition was the most radical right wing embodied in Vox.

Most of the electoral estimates published in the months prior to the elections anticipated an absolute majority in Congress for PP-Vox. As the election approached, the estimates shortened the distance between blocs, mainly due to the upward trend in the PSOE vote. One week before the elections, the probability, estimated on the basis of the average of polls, that PP-Vox would not obtain an absolute majority was already 40% (Llaneras et al. 2023). The predictions that continued to be published on the Internet and in foreign media (Spanish law prohibits the publication of estimates during the previous week) continued to shorten the distance between blocs.

Results

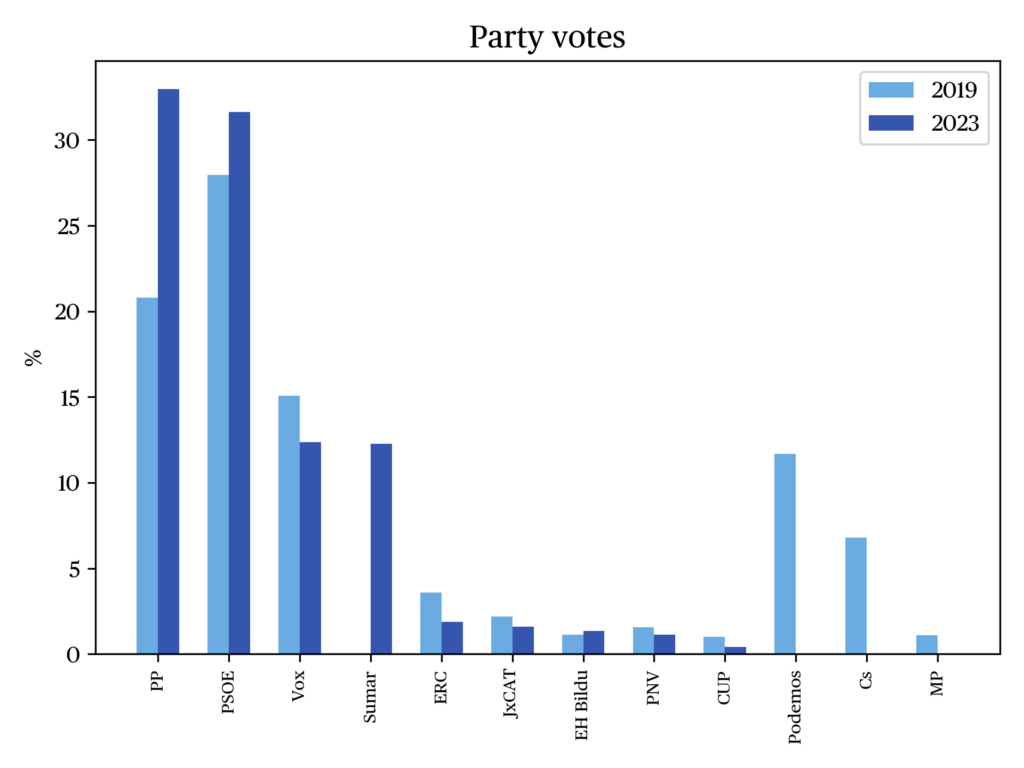

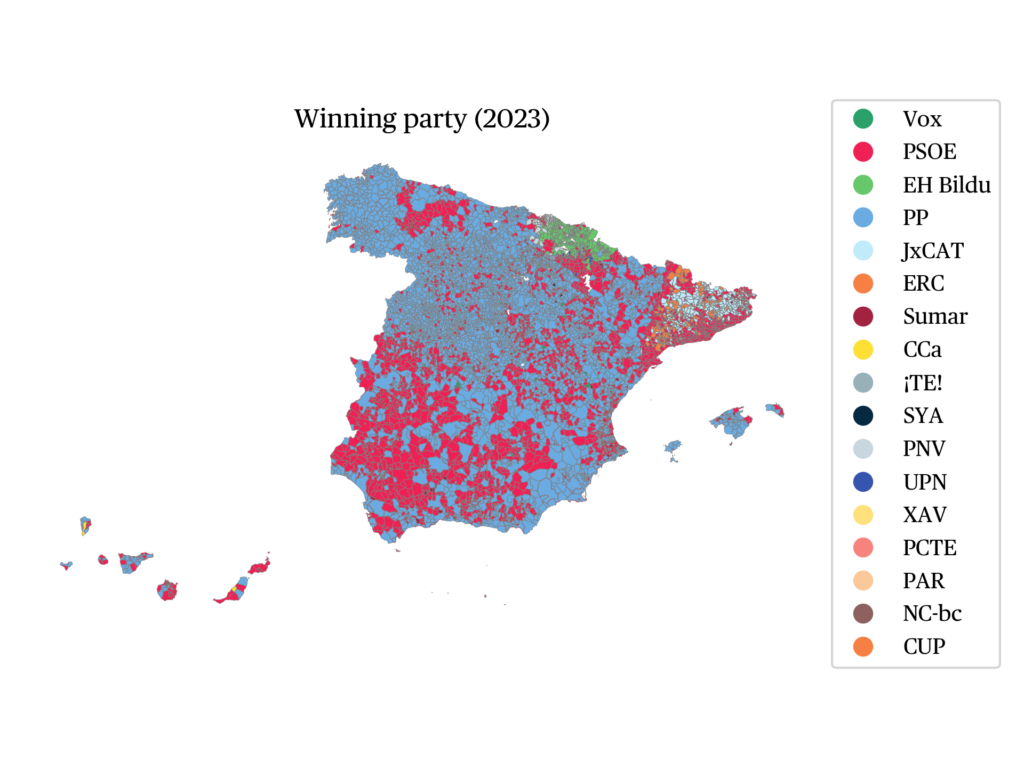

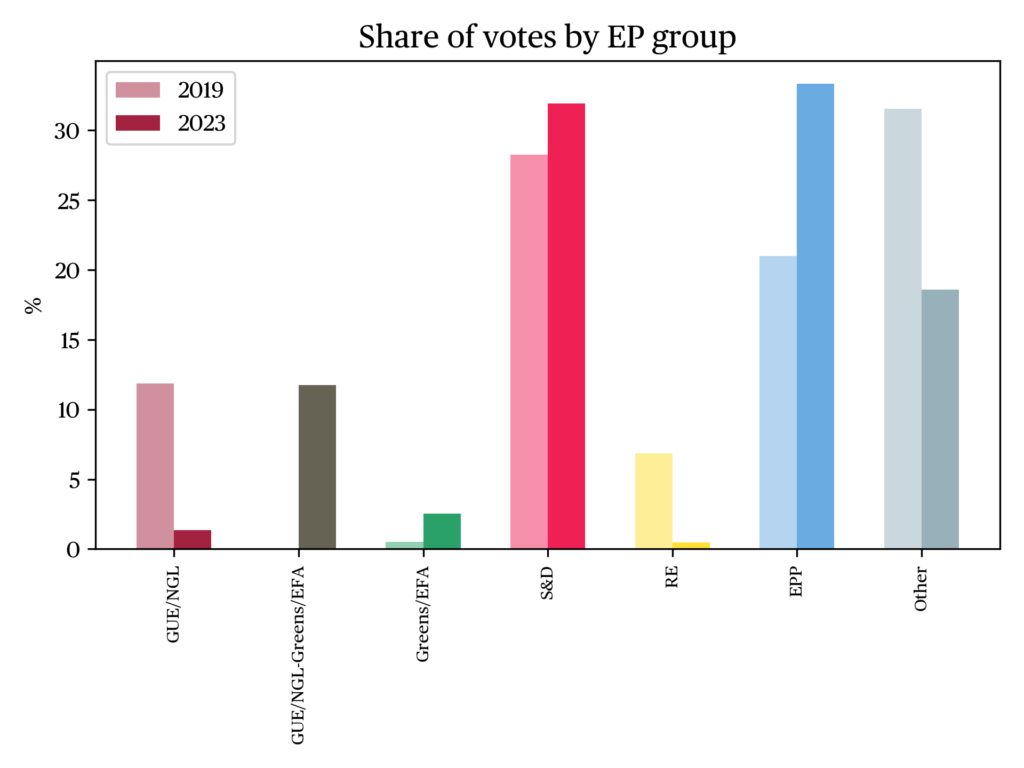

The PP won the elections of July 23, 2023, obtaining 137 seats and 33.1% of the vote. Its representation in Congress increased by 48 deputies and it raised its percentage of the vote by 13 points, substantially improving its 2019 results, in line with what the polls had predicted. Although the Socialists obtained second place, with 121 deputies and 31.7% of the vote, their final result did slightly improve the prediction of the polls’ average. If we look at the map of the most voted party, the PP won in Madrid, the Autonomous Regions of the Northwest and the Cantabrian coast (including Asturias, a traditional fiefdom of the left), in Aragon and in the Southeast (Eastern Andalusia, Murcia and most of the Valencian Community). For its part, the PSOE resisted in significant enclaves of the same Valencian Community and was the most voted party in the Southwest (in Extremadura, and in Western Andalusia, where it recovered a good part of the vote “borrowed” from the PP in the regional elections only two years earlier). The PSOE also won in two Northeastern ACs (Basque Country and Navarre) where nationalist or regionalist parties usually win, and obtained a very good result in Catalonia, at a great distance from the next party (Sumar) and from ERC, the most voted party in 2019 (see winning party maps). In summary, the electoral resistance of the PSOE in the Southwest and its victories in the three Northwestern ACs served to offset the substantial gains of the PP in the rest of Spain, allowing it to maintain a sufficient floor of representation to form an alternative parliamentary coalition to that of the right.

Since this investiture ended up depending on a very tight parliamentary majority, it is important to dwell on the results of the rest of the parties. Vox obtained third place (12, 4%) although it lost 3.3 percentage points of vote and 19 seats (more than a third of its representation) with respect to its 2019 result. Sumar’s result (12.3%) was barely a decrease of 0.5 tenths with respect to UP’s 2019 result but it was actually a similar decrease (2.7 percentage points of vote) if we consider the rest of the smaller parties that in 2023 also joined Díaz’s candidacy. However, Sumar lost only 7 deputies to Vox’s 19. In this intervened the electoral system that penalizes to a greater extent the electoral decline in small districts (those that allocate less than 6 seats) in which Vox had obtained a very good result in 2019. While Vox defended 21 of its 52 in these districts, Sumar — with more support in large cities — only 7 of its 38 seats in 2019, so Vox’s plunge in representation was considerably greater in seats than in vote percentage. Many pre-electoral studies erred precisely in the calculation of Vox seats in these districts — due to the difficulty of estimating the allocation of the last seat that in the real result can be decided by very few votes — and thus overestimated the overall result of the PP-Vox bloc.

Electoral support for nationalist parties suffered a clear decline (except for EH-Bildu) which was especially marked in Catalonia. Since it was in these regions where support for the nationalist parties fell that the socialists experienced the greatest electoral gains, it is worth asking to what extent there may have been transfers of this nationalist vote to the PSOE. This would require a more sophisticated analysis than we can offer here, although in the specific case of ERC in Catalonia, the sharp fall in representation and vote of this party suggests that such transfers seem quite likely. However, voter turnout was also lower in these regions, so that the electoral decline of the nationalists could also be due to a greater demobilization of this electorate (Riera, 2013).

For Spain as a whole, voter turnout was 70.4%, four points higher than in the previous elections of November 2019, a medium-low record if we consider the whole historical series. However, the turnout exceeded what was anticipated — the second best figure in the most recent electoral cycle that began in 2011 — taking into account, moreover, that the elections were held in July, with temperatures exceeding 40ºC and millions of citizens away from their usual place of residence. Turnout increased in three out of four Spanish municipalities (Newtral, 2023), most notably in Galicia and Castilla-León, remaining above average also in Aragón, Madrid, Castilla-La Mancha, Extremadura and Valencia; on the contrary, it fell below average in Western Andalusia, the Basque Country, and very especially in Catalonia (where it fell in 96% of the municipalities).

Finally, it is worth noting the change of trend in the most recent evolution of the party system, which in the period 2015-2019 had evolved towards a polarized multiparty system, with a low concentration of the vote for the first two parties (around 50%) and unusually high levels of party fragmentation in Spain (Rama et al. 2022). The result of 23J reverses this trend with an upward concentration of the vote (63%) and a notable reduction in fragmentation, both due to the electoral decline of Vox and Sumar and that of the nationalist parties. It would be rash, however, to speak of a return to bipartisanship, considering the parliamentary relevance that several nationalist parties continue to maintain.

Consequences and future prospects

Taking a European perspective, the results of the July elections in Spain -together with those of October in Poland- represent an important setback to what seemed to be an unstoppable upward trend of the European radical right-wing parties (European Conservatives and Reformists Group) after the accession of different members of this group to the governments of Italy, Sweden and Finland. The result is also a reinforcement for European social democracy, which consolidates the control of two governments out of the four main EU member states.

In any case, the new coalition government faces formidable challenges. The most obvious in the short term is the unpopularity of the amnesty law, which, beyond the mobilizations that took place coinciding with the investiture (some of them violent), has little support among broad sectors of the population, including many socialist voters (Hermida, 2023). The proposal has also been contested by broad sectors of the judiciary and deepens the growing distrust between the Executive and the Judiciary. Despite its failure to form a government, the PP accumulates considerable institutional power (possibly the greatest power ever enjoyed by an opposition party) as it governs in 11 of the 17 Autonomous Communities and controls the Senate, from where it can obstruct both the processing of the amnesty and other legislative initiatives.

In its favor, the PSOE-Sumar coalition has an institutional system that strengthens the Executive, in addition to the fact that it seems to have a greater internal consistency than that which characterized the PSOE-Unidas Podemos government. However, the parliamentary coalition that supports the government may prove to be weaker than in the previous legislature, due, on the one hand, to the presence of JxCat, but also, on the other hand, to the defection of Podemos (5 deputies) from the parliamentary group of Sumar a few weeks after the formation of the new government.

The data

References

Hermida, X. (2023, 25 July). Un 60% de los españoles considera que la amnistía es injusta y supone un privilegio. El País. Online.

Jabois, M. (2023, 25 July). Noche Nefasta de Sánchez. El País. Online.

Llaneras, K., Clemente, Y., & Grasso, D. (2023, 25 July). Datos y gráficos para entender el 23-J: Cataluña, el voto exterior y una vuelta a 2019. El País. Online.

Pérez, J. R. (2023, 24 July). La participación subió en tres de cada cuatro municipios en las elecciones del 23 J. Newtral. Online.

Rama J., Cordero, G., & Zagórski, P. (2021). Three Is a Crowd? Podemos, Ciudadanos, and Vox: The End of Bipartisanship in Spain. Front. Polit. Sci. 3:688130.

Riera, P. (2013). Voting differently across electoral arenas: empirical implications from a decentralized democracy. International Political Science Review, 34(5): 561-581.

Simón, P. (2020). The Multiple Spanish Elections of April and May 2019: The Impact of Territorial and Left-right Polarisation. South European Society and Politics, 25(3-4): 441-474.

Torcal, M. & Comellas, J. M. (2022). Affective Polarization in times of political instability and conflict. Spain from a comparative perspective. South European Society and Politics 27(1): 1-26.

citer l'article

Santiago Pérez-Nievas, Parliamentary election in Spain, 23 July 2023, Jun 2024,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue