Parliamentary election in Sweden, 11 September 2022

Sofie Blombäck

Associate Professor at the Mid Sweden UniversityIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Sofie Blombäck

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

The context of the election

The 2022 election was heavily influenced by a turbulent previous parliamentary period, with several simultaneous crises as a backdrop.

This turbulence is indicative of the breakdown of the traditional political blocs and the drawing of new political boundaries. For most of 20th century, Swedish politics consisted of a left-wing bloc, dominated by the Social Democrats (S), and a bourgeois bloc. The entry of the radical right Sweden Democrats (SD) into parliament in 2010 shifted these dynamics. Initially, the other parties imposed a strict cordon sanitaire and continued working together in the traditional blocs. After the 2014 election, this became increasingly difficult to sustain as the minority government was unable to get its budget through parliament. For a few weeks, the country was on brink of new elections being called, for the first time in modern history. Instead, most of the parties struck a bargain intended to exclude SD, and to a lesser extent the Left Party (V), from power. While this allowed the government to remain in place, it also marked the beginning of intensified discussions about the relationship to SD within several parties in the bourgeois bloc (Demker & Odmalm, 2022).

Normally, several factors in the Swedish constitutional system make it easy to form governments and ensure that even relatively weak minorities governments are able to function. However, both the 2014 budget crisis and the aftermath of the 2018 election indicates that this might no longer be true. The 2018 election resulted in the longest government formation process in Swedish history, lasting 134 days and needing three investiture votes in parliament, before a minority coalition between S and the Greens (MP) was in place (see Eriksson, 2019).

The 2018 election resulted in no government being possible without the support of the liberal Centre Party (C). C ideally wanted a centrist coalition, but were not able to persuade other parties. In the end C were forced to choose between supporting a left-wing government, being a part of a right-wing government dependent on SD or being seen as the cause of new elections being called. C, together with the Liberal Party (L), opted for a deal where they supported the S-led coalition in exchange for policy concessions (Aylott & Bolin, 2019).

Once formed, the S/MP government was far from stable. For the first time in modern history a Swedish prime minister lost a confidence vote, when the opposition parties on the right supported V’s motion of no confidence in June of 2021. After a period of negotiations, the same coalition was reformed, lasting until Stefan Löfven’s resignation as party leader and Prime Minister in November 2021. The very same day his successor Magdalena Andersson was elected, the right-wing opposition’s budget was adopted by parliament. This caused MP to leave the government, citing unwillingness to implement this budget, which in turn prompted the resignation of Andersson after a mere seven hours as Prime Minister. A new round of negotiations resulted in Andersson leading a single-party S minority government for the remaining months of the parliamentary term.

The root of this instability was largely the continued existence and growth of the SD, and the effect this had on the functioning of the party system. Neither of the two traditional blocs could hope to gain majority on their own, and C and L’s choice to support the left-wing government effectively split the bourgeois bloc in two. During the 2018-2022 parliamentary period, the largest party on the right, the Moderate Party (M), shifted its stance on SD, opening for some form of collaboration. This can be compared with how center-right parties in other European countries have started co-operating with the far right (Bale 2003; Heinze 2018). The smaller Christian Democrats (KD) made a similar shift. L were still uneasy about SD, but towards the end of the electoral period publicly stated that it would support an M-led government, even one dependent on SD support. C made the opposite choice, endorsing Andersson as their candidate for prime minister.

Besides the turmoil in the party system, the 2018-2022 period was characterized by multiple crises, some of which were curiously absent from the election campaign. The Swedish Covid-response was a non-issue in the campaign. There was unity around both health policies and the economic response between most parties, and the issue was largely seen as belonging to the past before the campaign started. The war in Ukraine had a profound effect on Swedish foreign policy. In the space of a few weeks S changed its policy of decade-long opposition to NATO membership, and Sweden applied for membership in May 2022 with broad support. The agreement between the leaders of the respective blocs effectively neutralized NATO as a policy issue before the campaign began.

Instead, most of the focus in the campaign was on two other crises: violent crime and energy prizes. Sweden has seen an unprecedented increase of gun violence, primarily among gang members in socio-economically deprived areas, pushing crime as well as economic and ethnic segregation to the front of the political agenda. In the last few months before the election, the issue of energy costs, in particular electricity and petrol, also became a focus of debate, with the parties outbidding each other in offering solutions to bring costs down before the winter months. Both these issues resonated with voters. Exit polls show that law and order and energy and nuclear power were named as very important determinants of their party choice by 50 and 45 percent of voters respectively, ranking them just behind the perennially important issues of Healthcare and Education. The energy issues in particular rose sharply in importance compared to the previous election, when only 26 percent cited it as very important (SVT 2022).

Turnout and election results

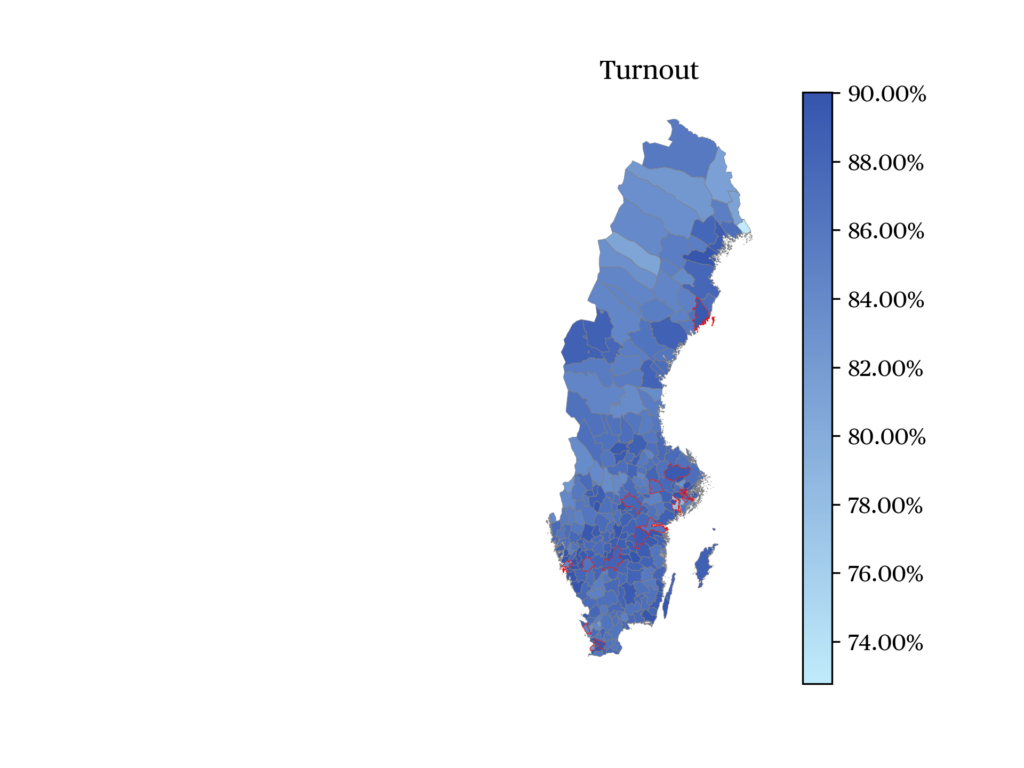

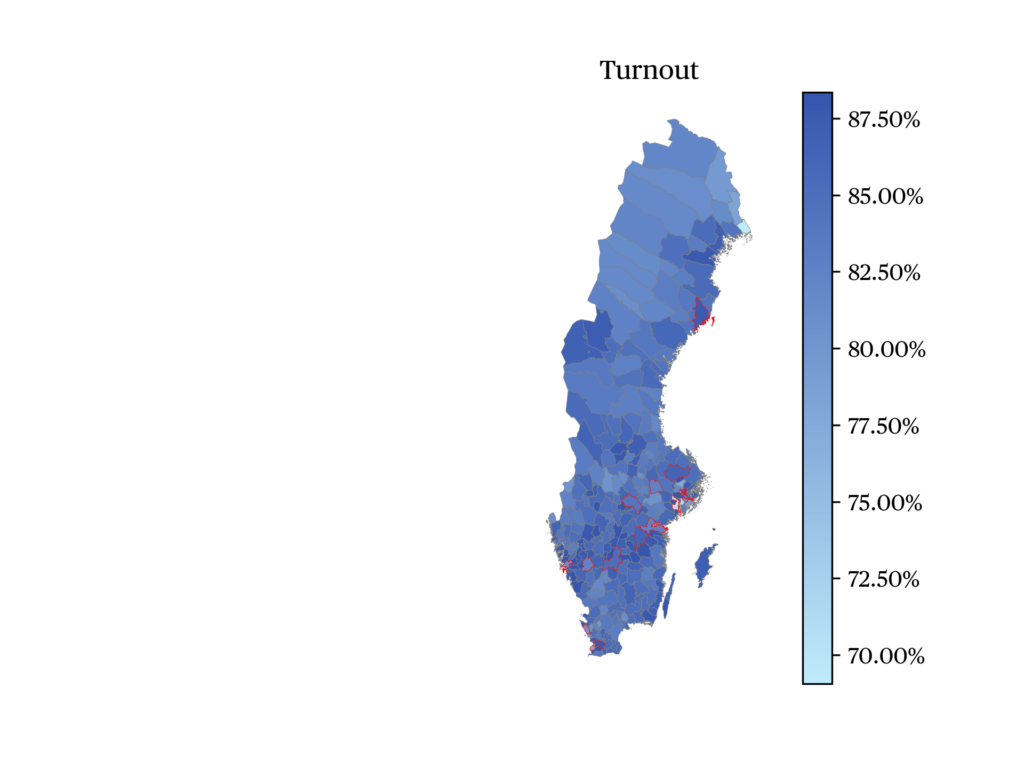

Sweden usually has high turnout levels and has seen an increase in turnout over the past few decades from a low of 80.1 percent in 2002 to 87.2 percent in 2018. However, this election broke that trend, with a decline in turnout to 84.2 percent. Areas with relatively low turnout in 2018 typically saw the largest decreases.

Among the reasons for the high turnout is that the electoral system is highly proportional and there are few barriers to participation. Registration is automatic, and early voting is available for 18 days before the elections. Voters can cast a ballot at any early voting polling place in the country, including on election day itself. Analyses of previous elections indicate that early voting is higher among groups that traditionally have lower turnout, highlighting its importance in making electoral participation more equal. In 2022 early voting again reached record levels, with almost half the voters casting their ballots either before election day or on election day but in a district other than the one they belong to (Dahlberg & Högström 2022).

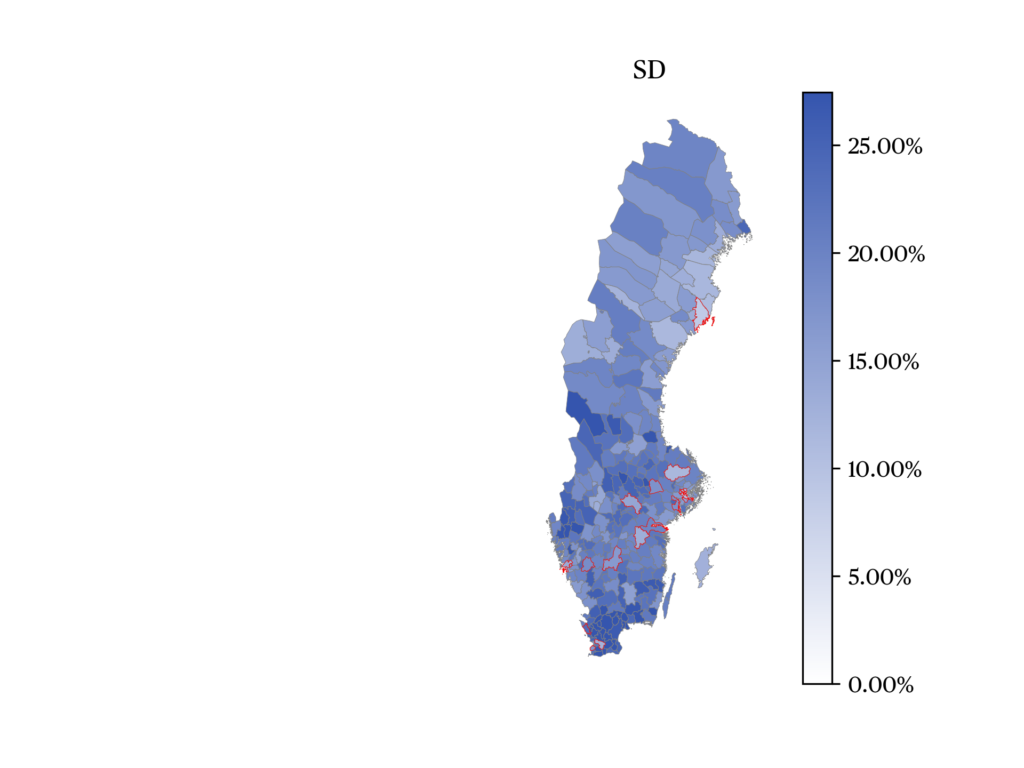

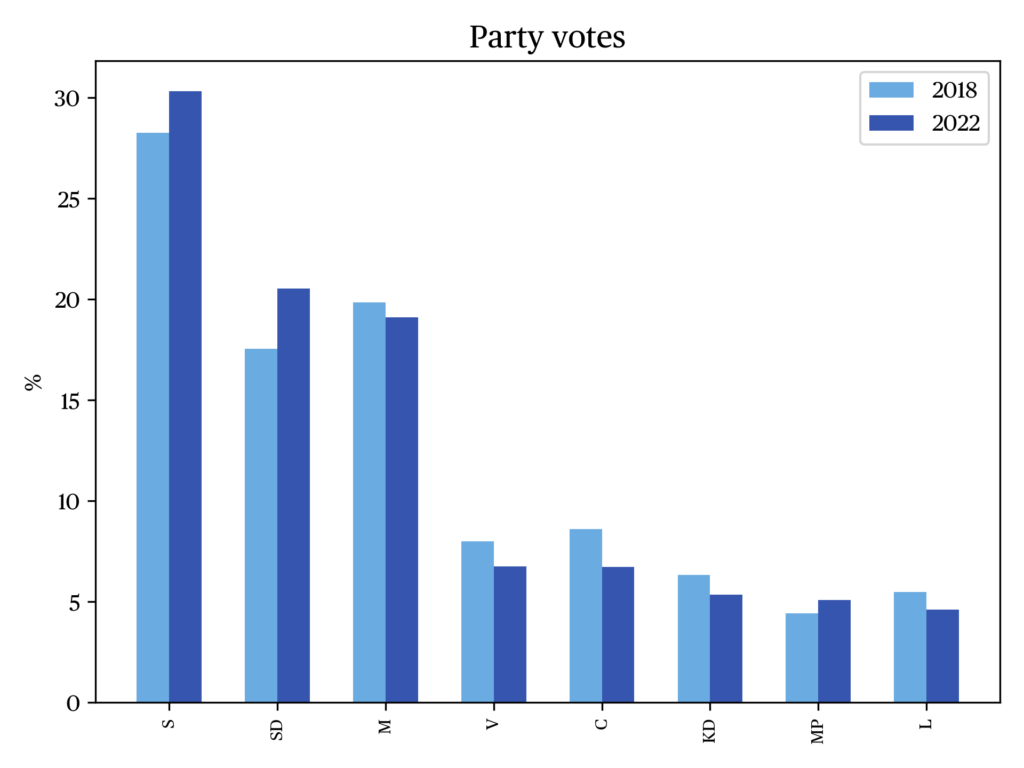

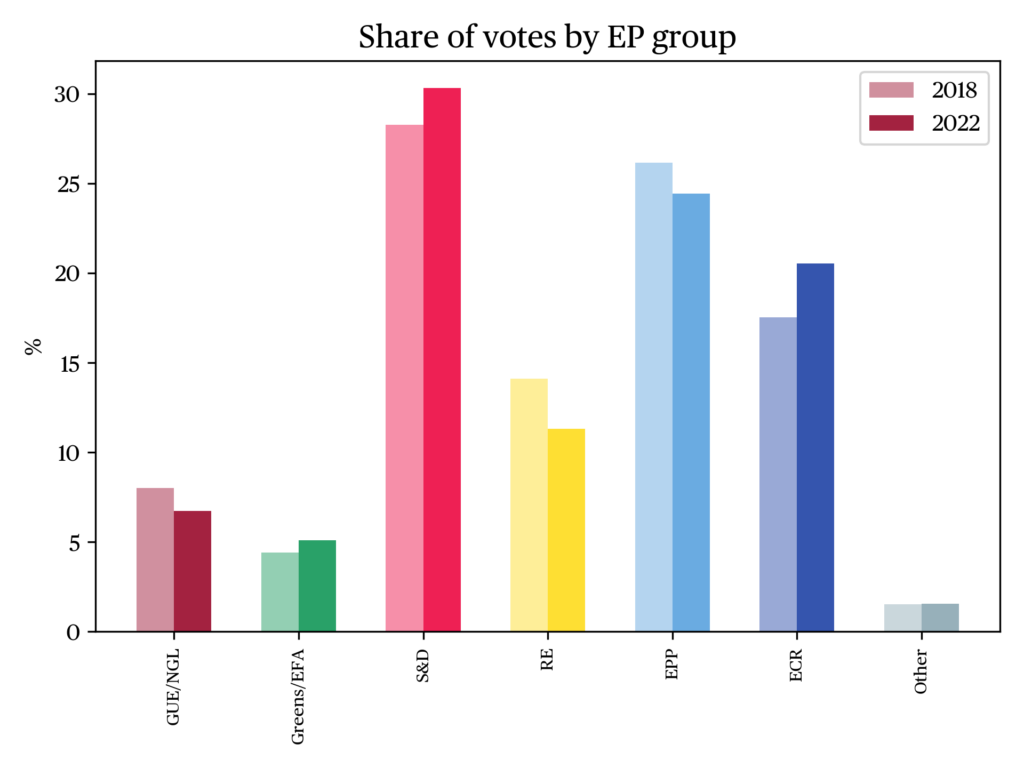

In terms of voter support, the most significant change was that SD for the first time became the second largest party, pushing M down to third place. This continues a trend of remarkable growth for the party that first entered parliament with less than 5 percent of the vote just twelve years ago. Furthermore, the party once again gained voters from both sides of the economic left-right divide (SVT 2022) highlighting shifts away from the established parties and traditional bloc politics.

At the other end of the scale, several parties have hovered around the 4 percent threshold in recent elections, but none have fallen below it since the 1990s. In the past electoral period, L and MP have often scored below or near the threshold in opinion polls. Likely, both were helped by strategic votes from supporters of their political allies, M and S respectively. This has been a recurring phenomenon in Swedish politics for decades (Fredén & Oscarsson 2015).

The two parties that had been in government since the last election, S and MP, both performed better than expected. For MP this meant staying above the 4 percent threshold, and for S that the party once again received more than 30 percent of the vote, recovering somewhat from the worst result in its history in 2018.

Despite the fact that both government parties increased their vote share, the balance between the two blocs shifted to the right. The government ‘support parties’ V and C both suffered losses. On the other side, losses among M, L and KD were offset by the increase for SD.

Trends in voting

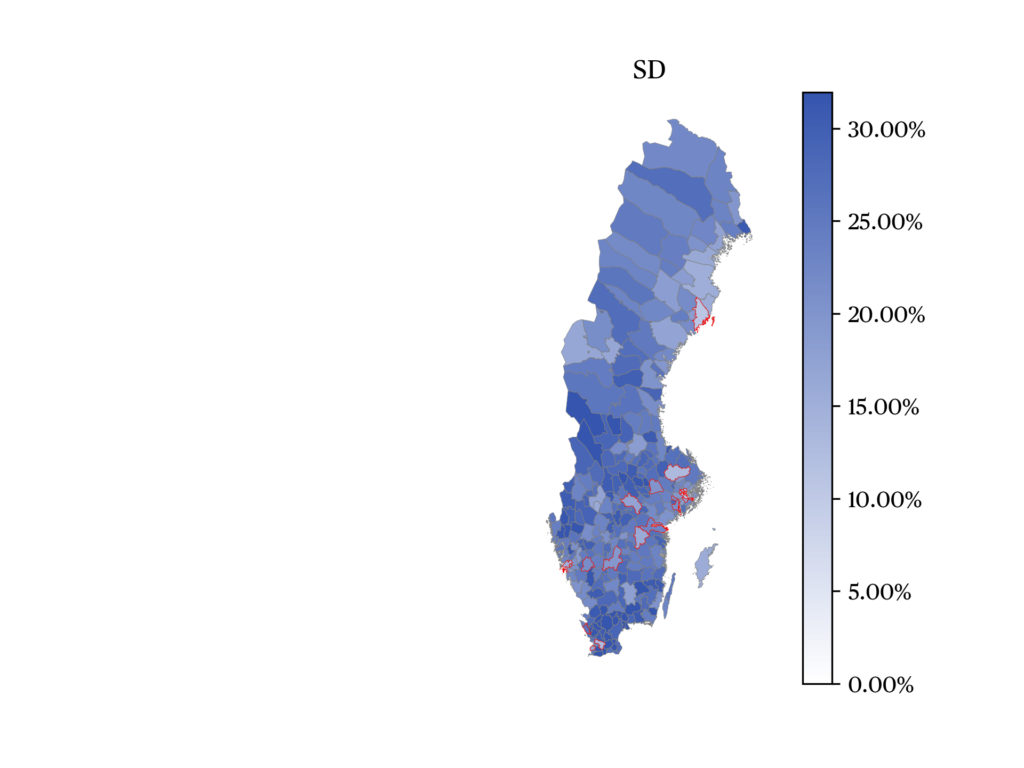

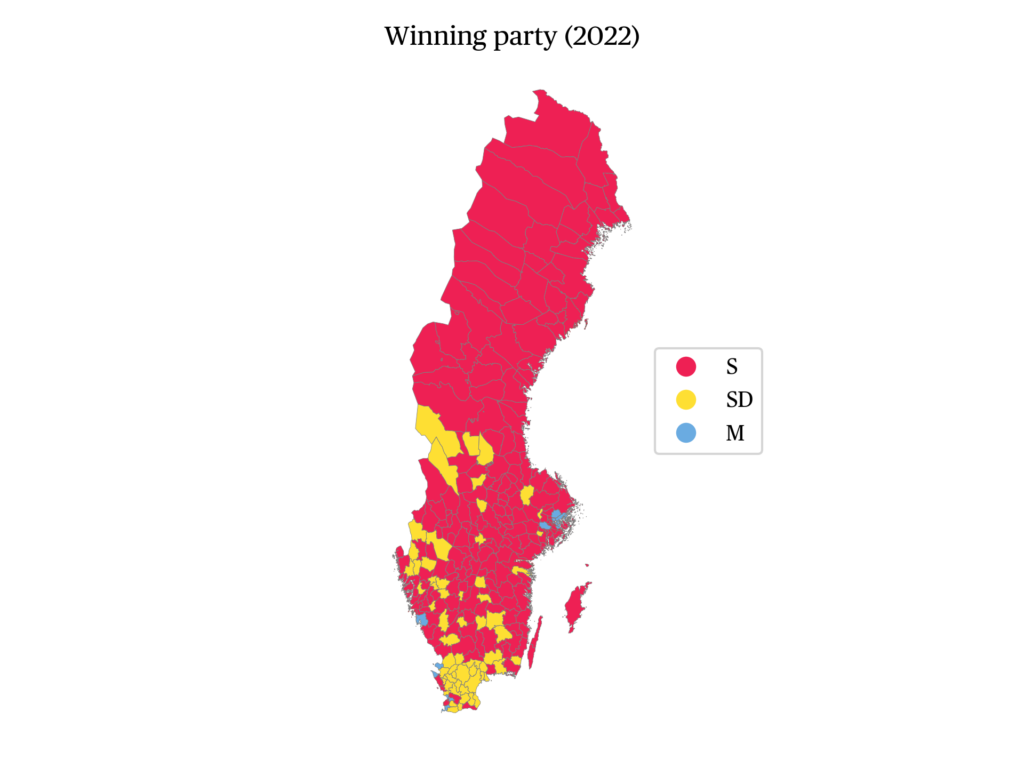

One of the clearest changes in the 2022 election was the change in geographical profile in the support for SD. Previously SD had always been strongest in the south, particularly in the Skåne region, while they fared less well in the traditionally left-leaning north. In 2022 the SD vote was spread more evenly across the country. The new trend can perhaps best be described as an urban-rural divide. The three largest cities were the only regions where SD did not make substantial gains, with Malmö being the sole constituency where the support for the party declined.

The second noteworthy trend is that there has never been a larger divide between the votes of men and women, at least not when it comes to which political bloc they support (Josefsson & Erikson 2022). In exit poll data, S was by far the largest party among women, with 34 percent of the female vote. Among men, S and SD were virtually tied, with 26 and 25 percent respectively. The vote share for SD among women was only 16 percent. Looking at the two potential coalitions, 56 percent of women voted for parties that supported Andersson as Prime Minister, while 56 percent of men voted for parties that supported Ulf Kristersson (SVT 2022).

Government formation

The election can be viewed as a choice between two candidates for Prime Minister, the incumbent Andersson (S) and challenger Kristersson (M). Each candidate was supported by a four-party “team”. Both teams had similar composition, with the candidate’s party and a smaller party that had cooperated before, one party closer to the political center, and one party on the flank.

The outcome of election gave a small advantage to Kristersson. The tight result and the fact that many ballots cast by early voters or abroad are not counted on election night meant that Andersson did not concede until 14 September, and formally resigned the next day. The Speaker of the Parliament held talks with all parties, and tasked Kristersson with trying to form a government.

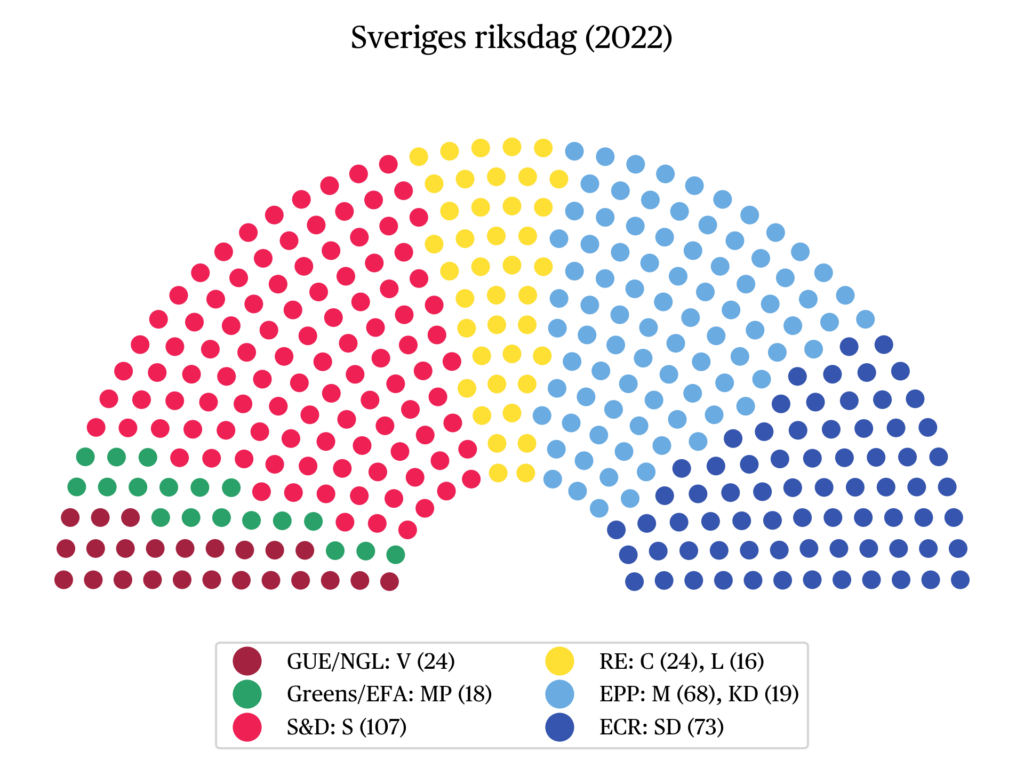

The final result of 176 seats for parties on the right meant that Kristersson in theory had support from a majority of the 349 members of parliament. Despite this, the formation process was not straightforward. SD was largest party in the potential coalition, which normally would mean having largest share of portfolios and the premiership. However, none of the other parties on the right were willing to support SD’s Åkesson as Prime Minister. Furthermore, L would not support any government that included SD.

After a few weeks of negotiations, the four parties on the right presented an agreement. Kristersson proposed a three-party minority government lead by M, with ministers from KD and L. SD were not included in the coalition but gained substantial policy influence, especially in the areas of migration, and law and order, in exchange for supporting the government. Furthermore, the party would be allowed to place staff within central government offices, in so called “co-ordination offices”. The four parties also committed to presenting and supporting a common budget bill.

The agreement sparked internal debate in L, which was cause of some concern given the slim majority. The close cooperation with SD is unpalatable to many in the Liberal party and several of the planned policy changes are not in line with party policy. In the end, all of L’s Members of Parliament voted in favor of the new government, but a few have publicly stated that they will not vote for parts of the policy agreement, once they are up for votes in parliament.

European and international perspectives

Sweden’s EU presidency in the first six months of 2023 is not likely to be affected by the change in government, since both blocs have similar attitudes towards the EU. Unusually for Swedish elections, M laid out a plan for the presidency in their election manifesto, but it was not subject of any real debate during the campaign (Blombäck, 2022).

Neither is the NATO-membership process likely to be affected. There is broad agreement in favor of membership among most parties, with the leaders of S and M making joint statements when the application process was begun in May. There is a tradition of consensus among the largest parties on important international issues, and both formal and informal channels for making sure that everyone is on board.

The government’s close co-operation with SD has been the subject of some international criticism, given the party’s roots in right wing extremist and neo-Nazi movements. L, in particular, has faced criticism from its European allies. ALDE has sent a fact-finding mission to Stockholm and L’s leader is at the moment of writing not welcome at ALDE meetings. The sole Liberal MEP has been allowed to remain in Renew, at least for the time being. It should be noted that there are two Swedish parties in ALDE/Renew, but having made a different choice as to which parties to cooperate with, C has not faced similar criticism.

There is another possible source of controversy concerning international relations; until very recently the other Swedish parties did not consider SD trustworthy on international issues. The new agreement, however, gives the party the right to be informed before the rest of parliament on certain EU-related issues. It remains to be seen how closely the government and SD will cooperate on international issues, and on how SD will use its new influence.

References

Aylott, N. & Bolin, N. (2019). A party system in flux: the Swedish parliamentary election of September 2018. West European Politics, 42(7), 1504-1515.

Bale, T. (2003). Cinderella and her ugly sisters: the mainstream and extreme right in Europe’s bipolarising party systems. West European Politics, 26(3), 67-90.

Blombäck, S. (2022) Fortfarande lite utrymme för EU-frågor i valrörelsen. In Bolin, N., Falasca, K., Grusell, M., & Nord, L. (eds.), Snabbtänkt 2.0 22 : Reflektioner från valet 2022 av ledande forskare. Sundsvall: Mittuniversitetet.

Dahlberg, S. & Högström, J. (2022). Förtidsröstandet är här för att stanna. In Bolin, N., Falasca, K., Grusell, M., & Nord, L. (eds.) Snabbtänkt 2.0 22 : Reflektioner från valet 2022 av ledande forskare. Sundsvall: Mittuniversitetet

Demker, M. & Odmalm, P. (2022). From governmental success to governmental breakdown: how a new dimension of conflict tore apart the politics of migration of the Swedish centre-right. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 48(2), 425-440.

Eriksson, L. M. (2019). Election Report Sweden. Scandinavian Political Studies, 42(1), 84-88.

Fredén, A. & Oscarsson, H. (2015). Skäl att rösta strategiskt i riksdagsval. In Bergström, A., Johansson, B., Oscarsson, H., & Oskarson M. (eds.), Fragment: SOM-undersökningen 2014, SOM-institutet, 377-386.

Heinze, A. S. (2018). Strategies of mainstream parties towards their right-wing populist challengers: Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland in comparison. West European Politics, 41(2), 287-309.

Josefsson, C. & Erikson, J. (2022). I valet 2022 har kön avgörande betydelse. In Bolin, N, Falasca, K., Grusell, M., & Nord, L. (eds.), Snabbtänkt 2.0 22 : Reflektioner från valet 2022 av ledande forskare. Sundsvall: Mittuniversitetet

SVT (2022). SVT Valu 2022. Retrieved 10.11.2022.

citer l'article

Sofie Blombäck, Parliamentary election in Sweden, 11 September 2022, Mar 2023, 98-102.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue