Parliamentary election in the Netherlands, 22 November 2023

Denny van der Vlist

PhD candidate in political science at the University of LeidenIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Denny van der Vlist

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

In the Dutch Parliamentary election, citizens vote to fill the 150 seats of the Tweede Kamer, the Dutch lower and only directly elected parliamentary chamber at the national level, which is at the core of legislative decision-making in the Dutch parliamentary system. To elect these seats, The Netherlands uses an extremely proportional electoral system with almost no entry barriers to parliament (see Andeweg & Irwin, 2014), leading to high levels of fragmentation of parliament and offering plenty opportunity for potential newcomers – hence, the notion of a “Dutchification” of politics. As a result, Dutch politics can be tumultuous at times with the 2023 election as a prime example.

The 2023 election took place on 22 November, approximately 2.5 years after the previous parliamentary election and 1.5 years short of the ‘normal’ four-year tenure. Although early elections have become the rule rather than the exception in recent decades and therefore not inherently related to political change, the 2023 election can be considered a fundamental shift in the Dutch political landscape. This article examines this shift by describing the context of the elections, the election results, and the direct aftermath of the elections.

Context of the election

The early election was initiated by the fall of the Rutte IV government in July 2023. The governing coalition, consisting of the Liberal Party (VVD), the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), Democrats ’66 (D66), and the smaller Christian Union (CU), collapsed due to problems in the processing of asylum requests (Lammers, 2023). In short, the system to accommodate and process the arrival of people requesting asylum could not deal with the number of applicants, leading to overcrowded locations and people sleeping outside in harmful conditions. Amongst the solutions to this crisis was a ‘diffusion law’ which arranged a more equal spread of incoming immigrants over The Netherlands. Within the VVD membership, however, there was significant resistance against this law, especially to the binding aspects that prescribed the central government the possibility to enforce the accommodation of people by the lower tiers of government (van Bekkum, 2023). Under the leadership of Rutte, being put under pressure by the members, the VVD subsequently advocated for stricter immigration policies and a change from earlier negotiated outcomes. Differences between the position of CU and D66 and the altered VVD stances could not be bridged, leading to the collapse of the government. The collapse triggered the announcement of early elections and had several other significant political consequences; most notably, Mark Rutte, after bringing his government to the breaking point, announced to step down as VVD party leader (Markus, 2023).

The VVD was, however, not the only political party in turmoil during this parliamentary period. The CDA had lost one of their most electorally important politicians, Pieter Omtzigt, during this parliamentary period. Omtzigt had been one of the MPs at the core of uncovering the Child Benefits Scandal (Toeslagenaffaire), which brought down the previous Rutte III Government (see Otjes & Hansma, 2021). Yet, after sustained tensions between himself and other members of the CDA leadership, he left his party and continued as an independent MP. By remaining the embodiment of the fight for a fair government, his popularity kept rising and prompted by the early election, he decided to create a new party: New Social Contract (NSC). An introduction that further altered the strategic calculations in the election – at the time of the announcement, NSC was even polling as the largest party (Peilingwijzer, 26 September 2023).

A final change was the collaboration between the Labour Party (PvdA) and GreenLeft (GL). Although not completely new – they had a combined list for the upper house – this was the first time that they were presented nationally as a single list on the electoral ticket; combining the two main left-wing political forces under one wing, with the intend to become a force that could contest for governmental power. To strengthen this claim, Frans Timmermans, European Commissioner and first Vice-chair of the Commission, was brought back from the EU to lead their campaign, potentially willing to fill the gap of being the ‘responsible and experienced’ leader that was left by Rutte (Peeperkorn, 2023). This provided a final change to the political landscape which had changed drastically in the months leading up to the 2023 elections. New parties had emerged, old faces left and returned, set against the backdrop of a fallen government on the theme of immigration. The stage had been set for a very volatile election.

The results

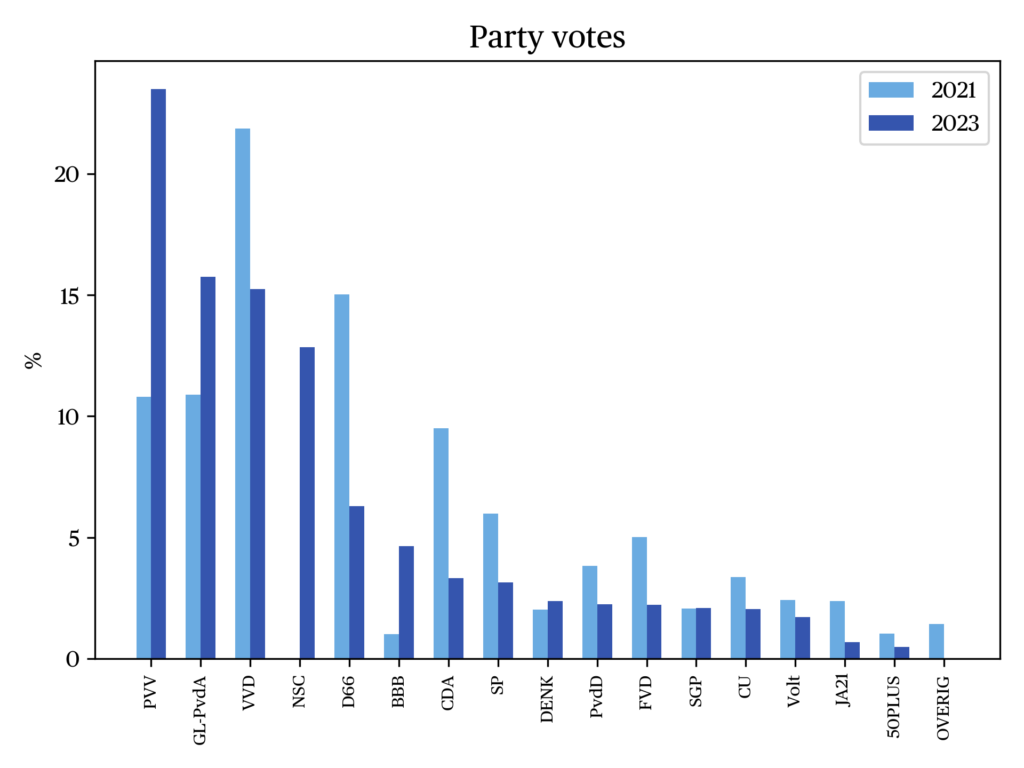

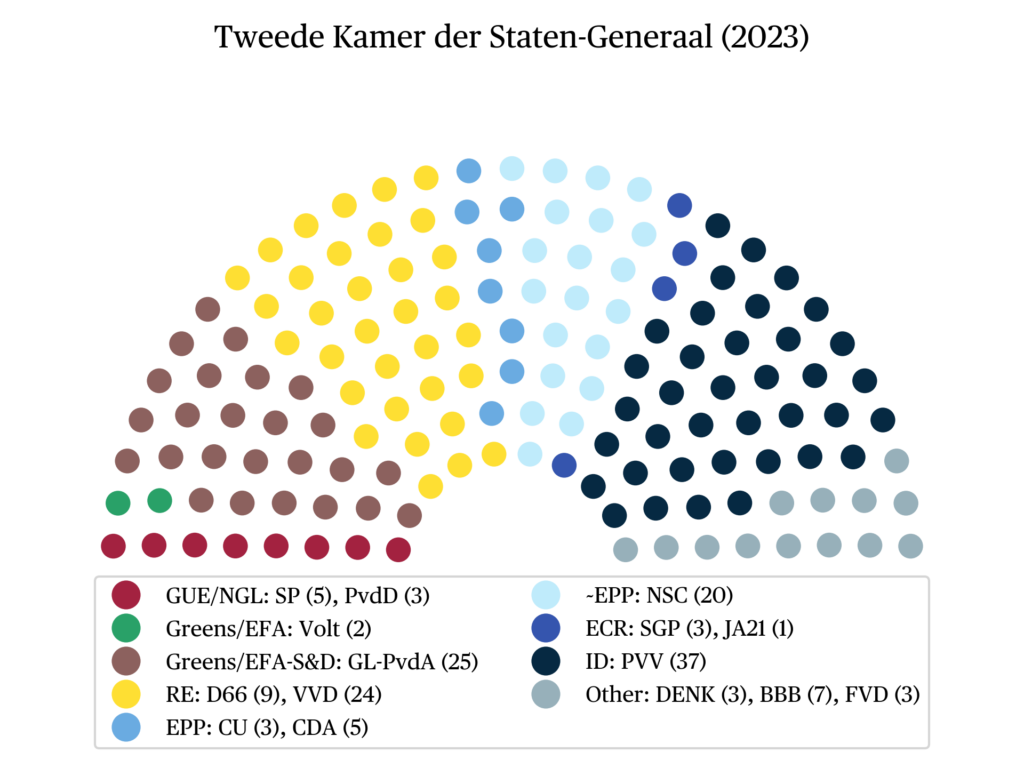

The Dutch election results once again provided highly fragmentized results. In total, 15 out of the 26 parties on the ballot managed to secure at least one seat in parliament, ranging from 37 seats for the largest party, and 1 single seat for the smallest party. Turnout was 77.75%, approximately one percentage point lower compared to the previous parliamentary election in 2021. A full overview of the parties that managed to secure a seat can be found in Figure a.

| Party | Votes | Vote share (%) | Seats | Seat change* | |

| PVV | Freedom Party | 2,450,878 | 23.49 | 37 | +20 |

| GL/PvdA | GreenLeft/Labour Party | 1,643,073 | 15.75 | 25 | +8 |

| VVD | Liberal Party | 1,589,519 | 15.24 | 24 | -10 |

| NSC | New Social Contract | 1,343,287 | 12.88 | 20 | New |

| D66 | Democrats ‘66 | 656,292 | 6.29 | 9 | -15 |

| BBB | Farmer-citizen movement | 485,551 | 4.65 | 7 | +6 |

| CDA | Christian Democratic Appeal | 345,822 | 3.31 | 5 | -10 |

| SP | Socialist Party | 328,225 | 3.15 | 5 | -4 |

| DENK | DENK | 246,765 | 2.37 | 3 | 0 |

| PvdD | Party for the Animals | 235,148 | 2.25 | 3 | -3 |

| FvD | Forum for Democracy | 232,963 | 2.23 | 3 | -5 |

| SGP | Political Reformed Party | 217,270 | 2.08 | 3 | 0 |

| CU | Christian Union | 212,532 | 2.04 | 3 | -2 |

| Volt | Volt | 178,802 | 1.71 | 2 | -1 |

| JA21 | Yes21 | 71,345 | 0.68 | 1 | -2 |

* Compared to the previous election results. Does not take into account changes during the parliamentary period.

Figure a · Overview of the results of the Dutch Parliamentary Elections of 2023

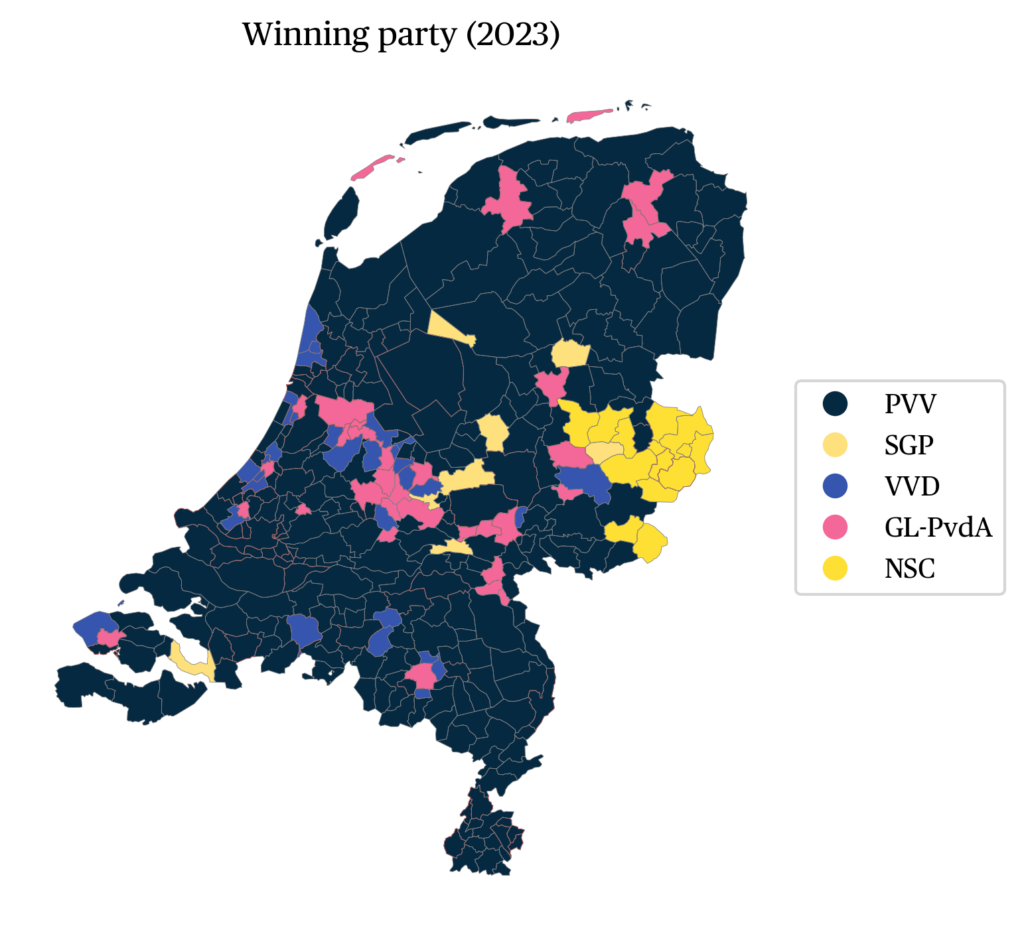

The 2023 election provided significant political change; 54 out of the 150 seats in parliament changed between parties. Much of this change can be attributed to the win of the PVV, which gained 20 seats, and NSC, which entered parliament with a total of 20 seats. Other winners included the BBB, a farmer-citizen party that also won strongly in the provincial election of April 2023, which jumped from 1 to 7 seats, and the combined list of Groenlinks and PvdA which gained 8 seats and got 25 seats. The incumbent government lost significantly, losing 37 seats of their 78-seat majority, with VVD losing 10 seats, D66 losing 15 seats, CDA losing 10 seats and CU losing 2 seats.

Other losing parties can be found in the bunch of smaller parties with the Socialist Party (SP) losing 4 seats out of 9, Party for the Animals (PvdD) losing 3 seats out of 6, Forum for Democracy (FvD) losing 5 seats out of 8, Volt losing 1 out of 3 and JA21 losing 2 out of 3 seats. The only parties that remained stable were the smaller DENK and Political Reformed Party (SGP), both at 3 seats. Finally, some had to leave parliament after losing their single seat; these are BIJ1, a left-wing progressive party, and several MPs who separated from their party and continued on their own. As a result of the 2023 election outcome, there are now two groups of parties in parliament based on their size; four relatively large parties with over 20 seats and 11 small parties with less than 10 seats.

The victory of the PVV by winning the plurality vote would be a surprise to many in July 2023. Only a few months prior in the April 2023 provincial elections, the PVV even lost a senate seat going from 5 to 4 (Otjes, 2023). Important explanations can be found in the campaign. The PVV has been the dominant issue-owner of the immigration topic in the past 20 years, but always had the downside of not being seen as a viable coalition partner. Consequently, any voter who agreed with the PVV but wanted to vote on a potential coalition partner would not vote for the PVV. These voters rather voted strategically for the VVD or other parties that seemed to capture both elements of stricter immigration policy and being seen as a potential governing partner. In this election campaign, however, the VVD under their new leadership openly welcomed the PVV as a viable coalition partner, effectively removing this distinction between the VVD and the PVV (Bhikhie, 2023). This resulted in two competing parties on the issue of immigration, whereas one of these parties – the PVV – was the issue owner. This positioned PVV perfectly from the very start and was leveraged by Wilders throughout the campaign.

In a more long term perspective, the 2023 parliamentary election also shows extreme volatility. Figure b provides the number of changed seats per election (1994-2023), and indicates that only the remarkable 2002 election with Pim Fortuin’s LPF (46 changed seats) can be considered close to the 2023 Dutch parliamentary election. With an average number of 32,9 changed seats per election in this period, the 54 changed seats of the 2023 election really stands out by extreme volatility. Even in comparison to elections in the previous decade, the difference in changing seats is also stark with changes of 23 seats (2012), 38 seats (2017) and 21 seats (2021) respectively, further indicating the important shift that has taken place in this 2023 election.

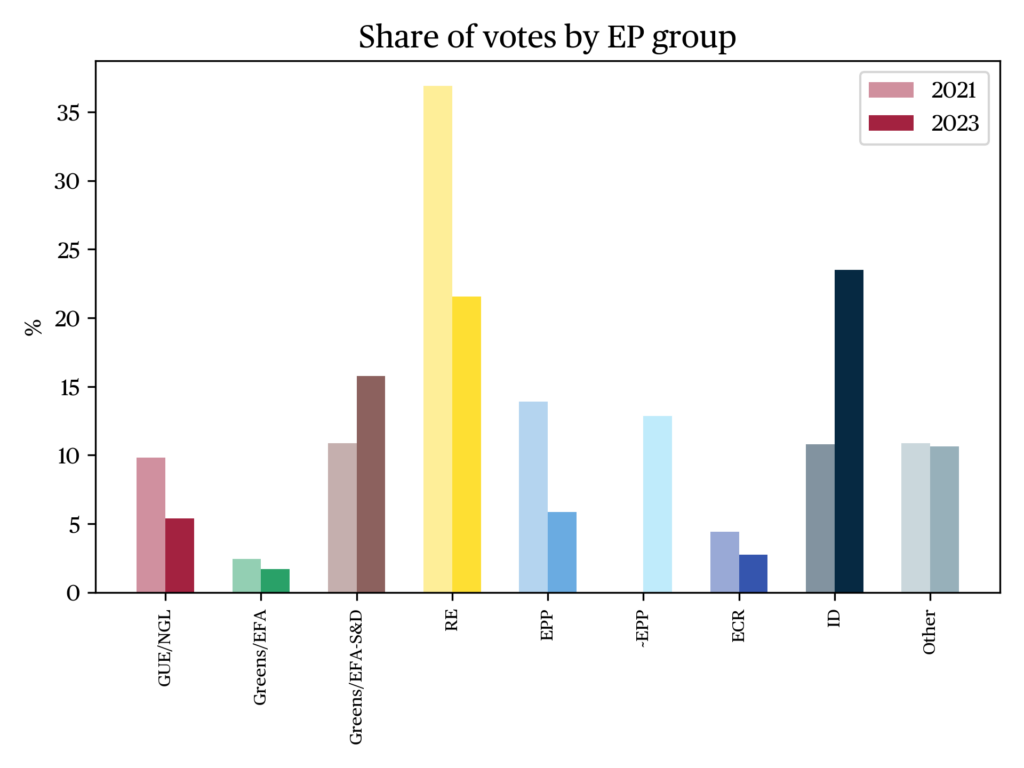

Moreover, the 2023 results solidify the three-bloc character of Dutch politics in the 21st century – also visible in Figure b. First, the left-progressive bloc that includes parties are left-wing in terms of their socio-economic policies and mostly progressive. This bloc has lost some votes in this 2023 election and has been losing in several elections in a row. Even though its main proponent, Groenlinks-PvdA, did win seats, the general seat share of this bloc has declined again with the SP, PvdD, Volt and D66 all losing seats. The traditional counterpart to this left-wing bloc would be the centre-right, with CDA and VVD as the largest parties. Even though both parties lost significantly, this bloc still represents around a third of the seats in parliament, with VVD and NSC being the main components in this parliamentary constellation. Both NSC and BBB seem to represent some parts of the former CDA, while the CDA remained barely alive with only 5 seats, further signalling the long-set decline of the traditional governing parties (van der Meer, 2021, p. 19). Finally, the third bloc is the conservative and radical right. For them, the elections can be considered a great success, with PVV winning the plurality of the vote – even though the PVV has cannibalized most other members, such as the FvD and JA21. The radical right has been growing steadily in the past decades and this election further reinforces that trend (Kanne & van der Schelde, 2024). Consequently, the Dutch parliament is now for the first time roughly equally divided between the three blocs, presenting a new political reality in Dutch politics.

| Election Year | Number of changed seats | Left-progressive | Centre-right | Conservative (Radical) Right |

| 1994 | 34 | 68 | 70 | 5 |

| 1998 | 25 | 75 | 72 | 3 |

| 2002 | 46 | 49 | 71 | 30 |

| 2003 | 24 | 65 | 75 | 10 |

| 2006 | 30 | 70 | 69 | 11 |

| 2010 | 34 | 67 | 57 | 26 |

| 2012 | 23 | 71 | 59 | 18 |

| 2017 | 38 | 64 | 57 | 25 |

| 2021 | 21 | 63 | 54 | 32 |

| 2023 | 54 | 47 | 52 | 51 |

Figure b · Volatility in the number of changed seats and distribution between the blocs.

The aftermath

Although the rise of the radical right has been a process that has been going on for several elections in The Netherlands, getting access to governmental power has been difficult. Governmental power has remained within the hands of the other blocs and has been controlled by the ‘traditional’ governing parties. The PVV, however, might have a chance this time. At the time of writing, there have been rather tumultuous discussions between PVV, VVD, BBB and NSC to form a governmental coalition. Within these talks, the new reality of a radical right party as a plurality winner also created new obstacles which were until now unseen in Dutch politics. The formation discussions between the four parties started with a discussion on the rule of law and the constitution because PVV’s election program violates the rule of law and the constitutional rights of Muslim citizens in several instances (Voermans, 2023). To show his willingness to cooperate, PVV leader Wilders subsequently agreed to place his views and wants that would violate the constitution “in the Freezer” for now (Righton, 2024). Other parties remain sceptical and if PVV can secure governmental power for the first time ever remains to be seen.

The data

References

Andeweg, R.B. & Irwin, G.A. (2014). Governance and politics of The Netherlands. Palgrave Macmillan, 4th Edition.

Bekkum, van D. (2023). Kabinet-Rutte IV vanaf de start van de formatie in 2021 tot aan de val op vrijdagavond. De Volkskrant.

Bhikhie, A. (2023). VVD-leider Yesilgöz sluit samenwerking met PVV niet langer uit. De Volkskrant.

Kanne, P. & van der Schelde, A. (2024). I&O-zetelpeiling: NSC halveert door opstelling in formatie, PVV profiteert. I&O Research.

Kiesraad (n.d.) Databank verkiezingsuitslagen. Online.

Lammers, E. (2023). Waarom de VVD juist op asiel het kabinet liet vallen. Trouw.

Markus, N. (2023). Mark Rutte was niet langer de oplossing, maar het probleem. Trouw.

Meer, van der, T. (2021). De verkiezingen van 2021 in longitudinaal perspectief. In Sipma, T., et al (eds.), Versplinterde Vertegenwoordiging. Nationaal Kiezersonderzoek 2021. SKON. 15-27.

Otjes, S. (2023). Provincial and Senate elections in the Netherlands. BLUE 4.

Otjes, S. & Hansma, L. (2021). The Netherlands: Political Developments and Data in 2020. European Journal of Political Research Political Data Handbook, 60 (1).

Peeperkorn, M. (2023). Frans Timmermans stelt zich kandidaat als lijsttrekker nieuwe PvdA/GroenLinks-combinatie. De Volkskrant.

Peilingwijzer (2023). Peilingwijzer op basis van peilingen I&O Research en Ipsos/EenVandaag, 26 September 2023. Online.

Righton, N. (2024). Wilders zet islamverbod en andere omstreden plannen formeel in de ijskast. De Volkskrant.

Voermans, W. (2023). Rechtsstatelijke doorrekening PVV-programma. Universiteit Leiden.

citer l'article

Denny van der Vlist, Parliamentary election in the Netherlands, 22 November 2023, Jun 2024,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue