Parliamentary election in Slovakia, 30 September 2023

Olga Gyárfášova

Professor at Comenius University in BratislavaIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Olga Gyárfášova

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

The 2023 Slovak parliamentary election took place on September 30, 2023. It was an early election (the next regular election date was scheduled for February/March 2024) and the ninth election since Slovakia´s independence on January 1, 1993.

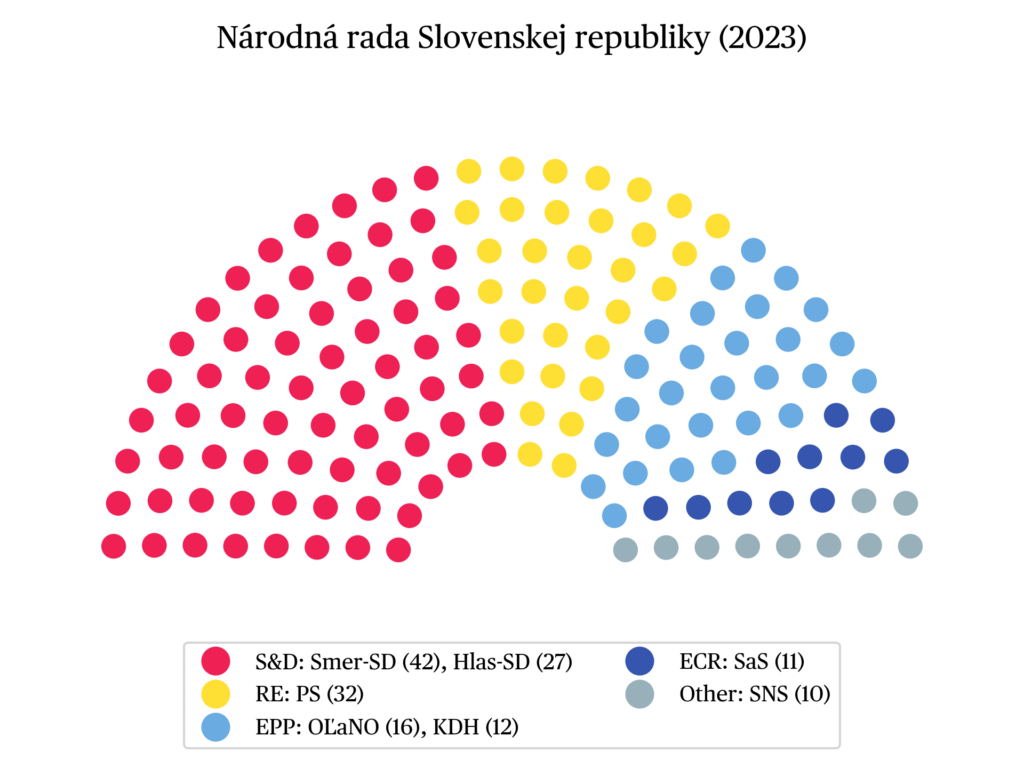

Turnout was 68.5 per cent, slightly higher than in the previous election in 2020 (65.8%). Twenty-five political entities were running, seven of which reached the five-percent threshold (for parties) or seven-percent threshold (for multi-party coalitions) required to obtain representation in the National Council. Slovakia uses a proportional electoral system with a single nationwide constituency. The National Council’s 150 seats are allocated using the largest remainder method with Hagenbach-Bischoff quota, a variant of the D’Hondt method. Party lists are semi-closed, with voters being allowed to cast up to four preferential votes for candidates of their preferred party.

Political and social context of the election

The election took place in a very tense atmosphere, following 3,5 years of political instability. In the 2020 election the Smer-SD party — which had been in power since 2006 with a short break in 2010-12 — was defeated by the center-right anti-corruption movement OľaNO. The main goal of the four-member pro-Western coalition that emerged from the election was to bring big cases of political corruption from the previous term to justice. Public expectations were high, with strong demands for decency and the respect of the rule of law. Alternation in power happened – Smer-SD went into opposition – but the expectations were not met. The government faced huge external and internal challenges: first the COVID pandemic, then high inflation, energy crises, and the war of aggression of Russia against Ukraine, Slovakia’s neighbor, which brought tens of thousands of war refugees to the country. Moreover, the government suffered from intra-coalition conflicts and animosities and was under continuous pressure due to Igor Matovič’s aggressive attitude towards other parties. In the eyes of the public the governing style of the coalition was perceived as chaotic. Trust in government reached historical lows — early 2023 saw the lowest level of trust since 1993 —, with only 14 per cent of the adult population still trusting Heger’s government (Standard Eurobarometer 98). By the end of 2022, the government faced a non-confidence vote in parliament. Few months later, in May 2024, it resigned and Ms. Zuzana Čaputová, Slovakia’s President, swore in a government of technocrats to lead the country to snap elections. In that way the standard coalition-opposition divide de facto disappeared. The electoral campaign was highly polarized, appealing predominantly to emotions of fear and anger among the electorate.

Results

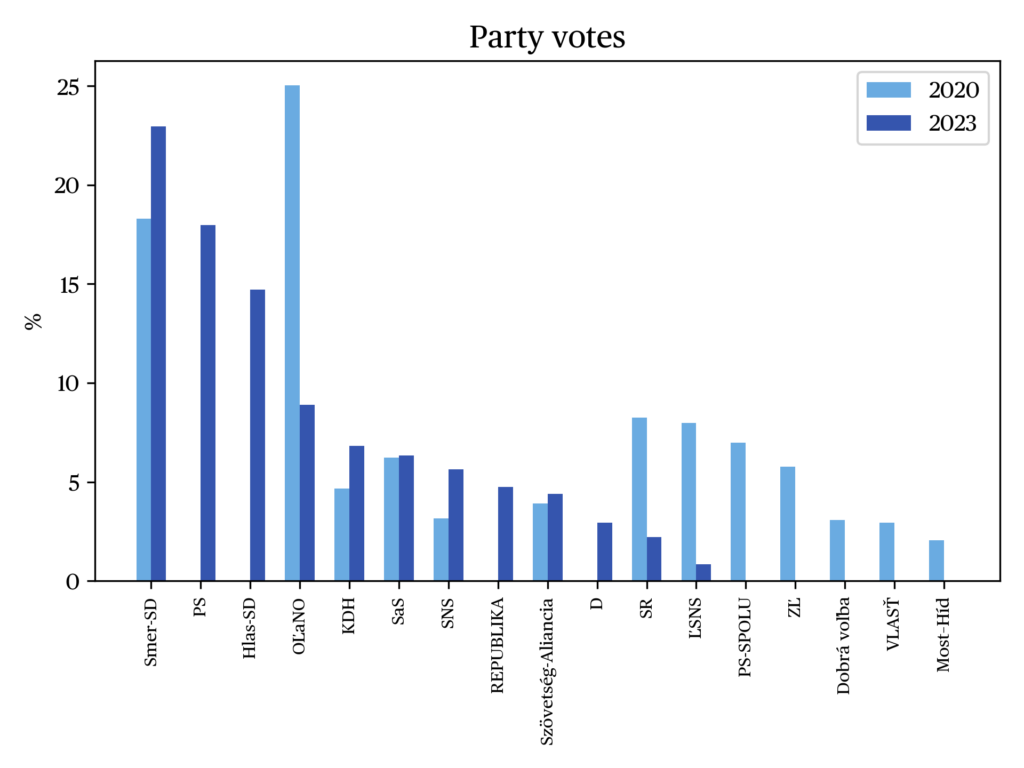

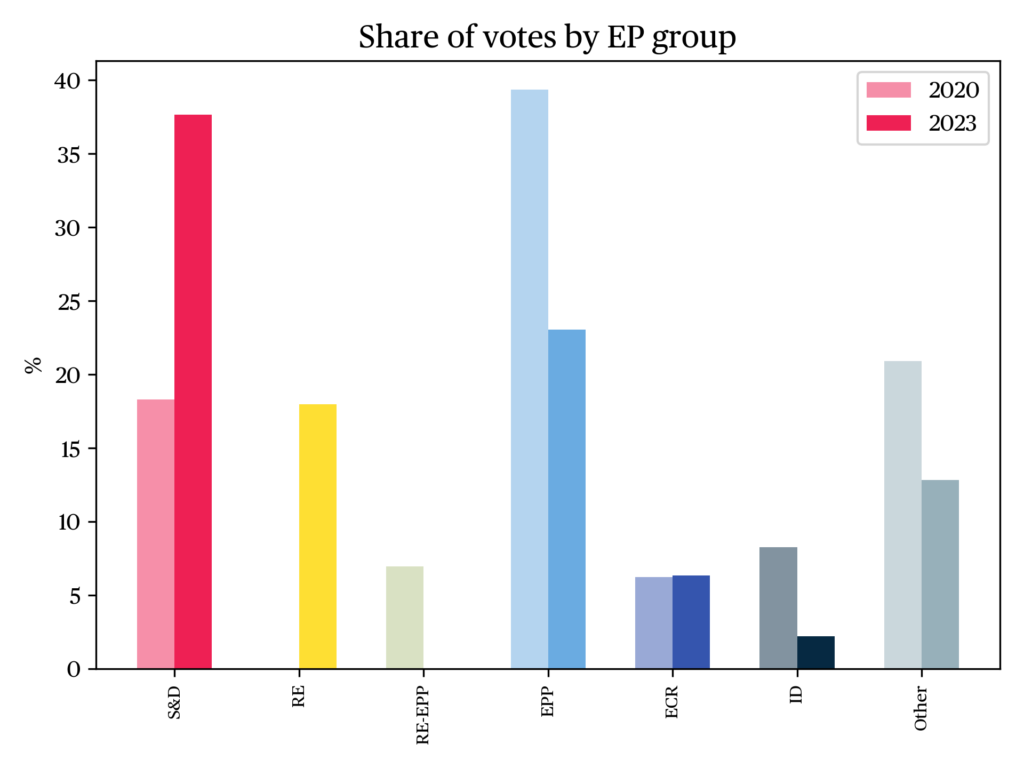

The winner of the 2023 election is the well-established party Direction-Social Democracy, a member of the Socialist and Democrats in the EP (Smer-SD, S&D) 1 led by ex-prime minister Robert Fico. The Slovak social democrats received 22.9% of votes and 42 mandates (+ 4 with respect to the previous election). Progressive Slovakia, a member of the Renew Europe group in the EP (PS, RE) and a newcomer to the Slovak parliament, came in second with 18% of votes and 32 seats 2 . PS leader Michal Šimečka was elected to the European Parliament in 2019. where he has also served as a vice president of the Renew Europe group. After winning a mandate in the national parliament, Šimečka resigned as an MEP. The party Voice-Social Democracy (Hlas-SD) took third place. Hlas-SD emerged in 2020 as a split from Smer-SD led by former Smer-SD member and short-lived PM Peter Pellegrini. In 2023, Hlas-SD obtained 14,7% of the votes and 27 seats. The clear winner of 2020 election, the conservative anticorruption party Ordinary People and Independent Personalities, a member of the group of the European People’s Party in the EP (OľaNO, EPP), won just 8,9% of the votes and 16 seats on a joint list with smaller allies. The Christian Democratic Movement, also a member of the European People´s Party in the EP (KDH, EPP), returned to the national parliament after two electoral cycles with 6.8% of the votes and 12 seats. Likewise, the ethnonationalist Slovak National Party (SNS) could celebrate its comeback to national politics with 5.6% and 10 seats. Last but not least, the classical liberal party Freedom and Solidarity, a member of the European Conservatists and Reformists in the EP (SaS, ECR), received 6.3% of votes and 11 mandates.

Among the most prominent losers of this election are the extreme right-wing parties — most importantly the People’s Party Our Slovakia, (ĽSNS, Non-Inscrits) and its splinter movement Republic (Republika). The extremists, who celebrated an electoral breakthrough in 2016, are now out of parliament. One of the possible explanations for this fiasco is the radicalization of the Smer-SD party, which was able to absorb parts of their electorate. Among the losers is also the new Democrats (D) party led by ex-center-right prime minister Eduard Heger, who replaced Igor Matovič in March 2021. Despite having several former ministers running on their list, the Democrats received less than 3% of votes. Another member of the incumbent coalition, We are a family (SR) suffered a similar fate. Finally, the leader of the fourth coalition member party Za ľudí (For People) Veronika Remišová “saved” herself only by joining OľaNO; her former party, originally founded by former president Andrej Kiska, practically faded into irrelevance. In the end, all parties that defeated Robert Fico in 2020 by winning a constitutional majority were severely defeated. To complete the list of unsuccessful parties, one should mention the fragmented political representation of the Hungarian minority — not a single one of the parties of this space met the required quorum.

Government formation and campaign

The new government was formed shortly after the election by three parties: Smer-SD, Hlas-SD and SNS. It holds a narrow majority of 79 seats in parliament. The leader of the strongest party, Robert Fico, became Slovakia’s PM for the fourth time.

The structure of the political competition was determined mostly by the growing salience of sociocultural issues: illiberal conservatives promoting traditional family values and a hierarchical social order stood vis-à-vis liberals and progressives advocating strong minority rights, including demands for registered partnerships for the LGBTI+ minority 3 . However, the cleavage was not “only” about cultural values, but also about the basic features of liberal democracy. As the Hungarian political scientist Zsolt Enyedi argues, “illiberal conservatism is hostile to check and balances, state neutrality, and the ability of the mass media and civil society to hold decision makers accountable” (Enyedi, 2023: 12). Linked to civilizationalist ethnocentrism and paternalist populism (ibid.), illiberal conservativism is the toxic combination responsible for democratic backsliding observed in several Central European countries since the 2010s. The rise of illiberalism led to a reduction of the political competition to a contest between two polarized camps, one of which represents regress to authoritarianism while the other tries to save the principles of the rule of law and liberal democracy (cf. Greskovits, 2015; Rupnik, 2023). Under this backdrop, the 2023 Slovak election was rightly called “critical” as it decided not only about the routine alternation of power, but also about the future direction taken by the country.

The two strongest parties are also the champions of the two main competing blocs. The nationalistic albeit left-leaning Smer-SD promotes a “sovereign Slovak foreign policy” reminiscent of Viktor Orbán’s in its stance towards the EU, Ukraine, and Russia. On the other hand, Progressive Slovakia stands for a markedly pro-European, liberal, and progressive agenda. The civilizational difference between these two parties can be illustrated by a very simple indicator: in the 2023 election, PS was the first party in Slovakia’s democratic history to run with a gender-balanced list; meanwhile, the first female Smer-SD candidate in the party’s list ranked only in 33rd position.

Voters and their choices

Slovakia is characterized by a high degree of electoral instability at the party-system level — in each election new parties emerge and are successful, and voters’ behavior is considered very volatile (cf. Haughton & Deegan-Krause, 2015; Linek & Gyárfášová, 2020). The 2023 parliamentary election is no exception to this rule, with massive in- and outflows of voters. A new party, Hlas-SD, a splinter from Smer-SD, entered the parliament. PS is also a newcomer in the national parliament. It attracted 2.5 times more voters than in 2020, when it ran in coalition with the center-right SPOLU. All four governing parties faced massive voter outflows, with more than half of their former electorate voting for other parties. The entire government coalition was severely “punished” for its governing style despite many last-minute social packages.

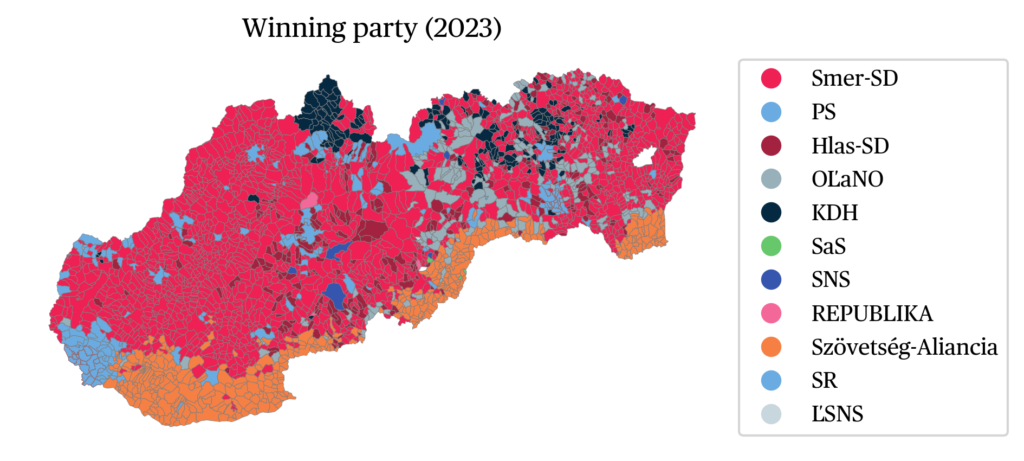

The parties’ voter bases have a very different sociodemographic structure, especially as regards age and education. According to the exit poll results (FOCUS, 2023), PS clearly won among the age cohort up to 39 years and among university education holders, while among university students it even gathered over 40% of votes. On the other hand, Smer-SD enjoyed above-average support among the elderly and middle-aged population. A rural-urban divide is also visible: PS has a stronghold in the capital Bratislava and other big towns across the country, whereas Smer-SD is stronger in smaller towns and rural areas.

The electorate of the two nominally social democratic parties Smer-SD and Hlas-SD show significant differences. Whereas Smer-SD addressed mainly the elderly and rural voters, Hlas-SD was successful among younger urban voters. As for their ideological positioning, while both parties maintained a left-leaning economic profile, they differed on the sociocultural dimension, with Hlas-SD being more liberal with an outreach to middle-class social- democratic voters. Their joint electoral potential reached 38%, more than double Smer-SD’s 2020 result. As post-electoral developments led to close cooperation within a new governmental coalition, it can be assumed that the divide was in fact transitory and the social-democratic parties will reunite in the future.

The largest ethnic minority in Slovakia are Hungarians (8.4 % of the population according to the 2021 census). The Hungarian minority is territorially concentrated in southern Slovakia along the border with Hungary. Until 2020, the Hungarian minority was continuously represented in national politics. In the 2023 election, however, the Hungarian vote was fragmented. The strongest Hungarian party, Szövetség-Aliancia, received 4.4% of the votes, while two smaller parties each took less than 1% of votes. The vote for Hungarian parties is stronger in the southern regions (see “the data”). Still, Hungarian parties are more successful in local and regional politics than at national level.

Looking at the geography of the vote (see “the data”), we see the Smer-SD winning in a majority of Slovak municipalities. Among the exceptions are areas of high ethnic Hungarian presence, where Szövetség-Aliancia was able to win. PS won in the largest cities, while in Northern Slovakia (above all in the region of Orava), KDH was stronger due to a higher concentration of Christian voters. Finally, there were further exceptions to the Smer-SD dominance in areas specifically targeted by some parties’ campaigns, or where local candidates ran on party lists.

Challenges ahead for the new government

Fico’s new government faces several difficult tasks. Key challenges include easing societal tensions, demonstrating its capacity to address the needs of all groups of citizens, and regaining trust towards the political system. Slovak society is likely to remain polarized along political lines in the coming years. The economy, social affairs, and public finances will also be in the foreground during the next legislative term. Many social groups — above all single parents, pensioners living in single households, large families, and families with disabled members — are economically deprived and face rising prices for energy, housing, and food, a situation that calls for targeted social assistance. Another important challenge is the necessity to consolidate public finances after two years of considerable debt growth. Whether the efforts to improve the efficiency of the judiciary and consistently prosecute cases of corruption and abuse of power will continue is unclear.

The outcome of the 2023 parliamentary election in Slovakia also has broader relevance for European politics, especially in the light of the unfolding geopolitical crises. There are concerns — based on the old-new prime minister’s statements — that the continuity of Slovakia’s foreign policy might be broken, and that the country will be a less reliable and predictable partner in the EU and NATO. This would be most evident from the termination of Slovakia’s military support for Ukraine, the new government’s opposition to Ukraine’s EU membership bid and its openness towards Moscow’s narratives and policies. On the other hand, Fico has often presented himself as a pragmatic politician who is willing to continue the pro-EU policies of his predecessors. Which of his many faces will predominate in the coming four years remains to be seen.

The data

References

Enyedi, Z. (2023). Illiberal conservativism, civilizationalist ethnocentrism, and paternalist populism in Orbán´s Hungary. CEU- DI Working papers 2023/03.

FOCUS (2023). Data from the exit-poll conducted on September 30 for TV Markíza. Internal data set.

Greskovits, B. (2015). The Hollowing and Backsliding of Democracy in East Central Europe. Global Policy, 6(S1): 28-37.

Haughton, T. & Deegan-Krause, K. (2015). Hurricane Season: Systems of Instability in Central and East European Party Politics. East European Politics and Societies 29(1): 61–80.

Linek, L. & Gyárfášová, O. (2020). The role of incumbency, ethnicity, and new parties for electoral volatility in Slovakia, Czech Political Science Review, XXVII(3): 303-322.

Rupnik, J. (2023). Illiberal Democracy and Hybrid Regimes in East-Central Europe. In Kolozova, K. & N. Milanese, N. (eds.), Illiberal Democracies in Europe: An Authoritarian Response to the Crisis of Illiberalism (pp. 9-16). The Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies.

Standard Eurobarometer 98 – Winter 2022-2023 (2023). Online.

Notes

- Smer-SD and Hlas-SD are both members of the Party of European Socialists. However, after forming a government coalition with the Slovak National Party (SNS) in 2023, their memberships in the party and the S&D group were suspended.

- In the 2020 election, PS, running in a coalition with the party TOGETHER (SPOLU, RE) missed the electoral threshold by a mere 0.04%. This coalition split shortly after the election and PS ran as a single party in the 2023 election.

- Slovakia is one of the few EU countries which does not recognise same-sex marriage or civil unions. The Constitution of Slovakia has limited marriage to opposite-sex couples since 2014.

citer l'article

Olga Gyárfášova, Parliamentary election in Slovakia, 30 September 2023, Jun 2024,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue