Presidential and legislative elections in France, April-June 2022

Anne-France Taiclet

Associate professor in Political Science at Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne UniversityIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Anne-France Taiclet

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

The 2022 national election sequence in France (presidential and legislative elections) came at the end of a five-year period in which most intermediate elections (the 2020 municipal elections and the 2021 departmental and regional elections) had been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to the ongoing health crisis, the results of these intermediate elections had not been easy to interpret. Hence, it was unclear to what extent the French party system had really been reconfigured by the election of Emmanuel Macron in 2017 and the emergence of his new party (LREM, now Renaissance), which claims a central position in the political life of the country. Beyond the designation of a new government for the next five years, these national elections were therefore an exercise in measuring the country’s political situation, and, in particular, the balance of partisan forces. While neither the results of the presidential election nor the results of the legislative election allow us to draw definitive conclusions about the effects of a political reconfiguration that does not seem to be complete, they still confirm a long-lasting trend: citizens appear to have become increasingly alienated from representative institutions, an evolution which weakens the mobilizing capacity of democratic rituals and, consequently, the political legitimacy and strength that they confer on those in which power is vested.

The confirmation of a democratic disaffection

The first round of the presidential election concluded a campaign that seemed to have generated more disappointment and frustration than enthusiasm. The late entry into the campaign of one of the main contenders, incumbent president Emmanuel Macron, in a context of a very gradual exit from the pandemic period and the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, gave way to a media campaign that was very much focused on security, migration and “identity” issues, while opinion polls showed higher levels of concern about economic and social issues (purchasing power, access to the health system). With polls repeatedly giving the Rassemblement National a high probability of qualifying for the second round of voting, a shadow was cast over the campaign, in which the candidates’ positioning vis-à-vis the far-right became a central issue. In the ballot box, this campaign, which, as various opinion polls have underlined, has generated little interest among voters, ended with both a concentration and a dispersion of votes.

On one hand, in the first round, the votes concentrated on only three candidates, with all other candidates obtaining very low results. The presidential election has always been the most mobilizing ballot in France, due, at least in part, to the presidentialism of the Fifth Republic and the strong personalization of political issues it generates. In 2022, these mechanisms were again in full play: the only three candidates who managed to obtain at least 20% of the vote were those who benefited from the highest levels of notoriety and identification, especially since they had already played a major role in the 2017 election.

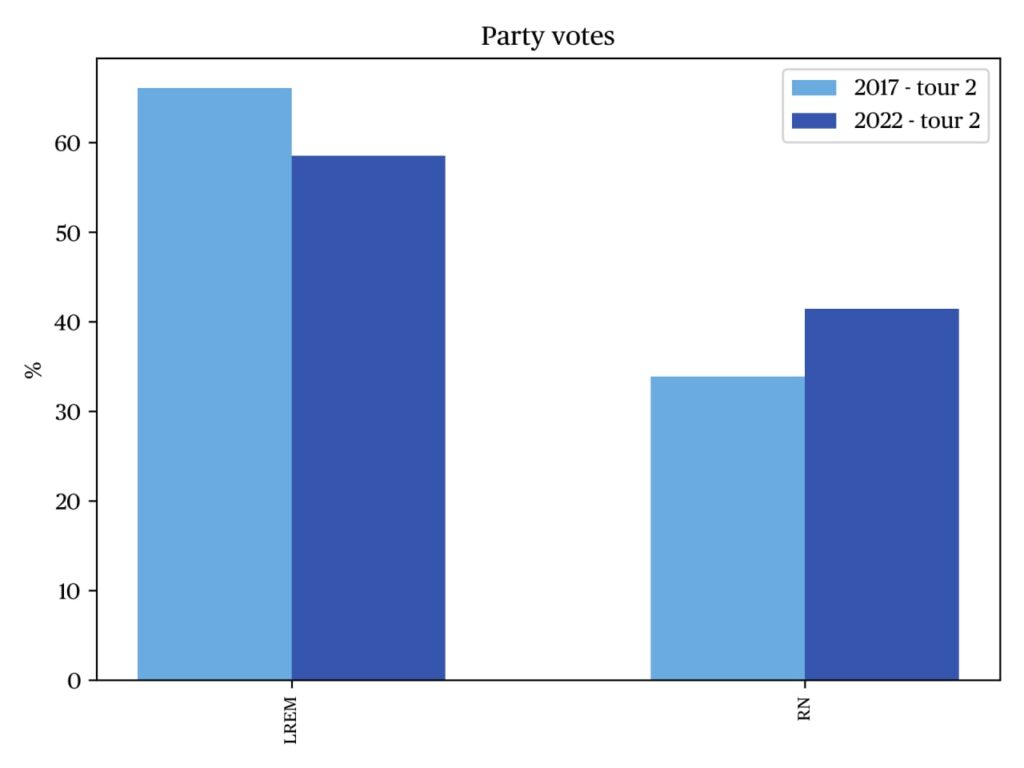

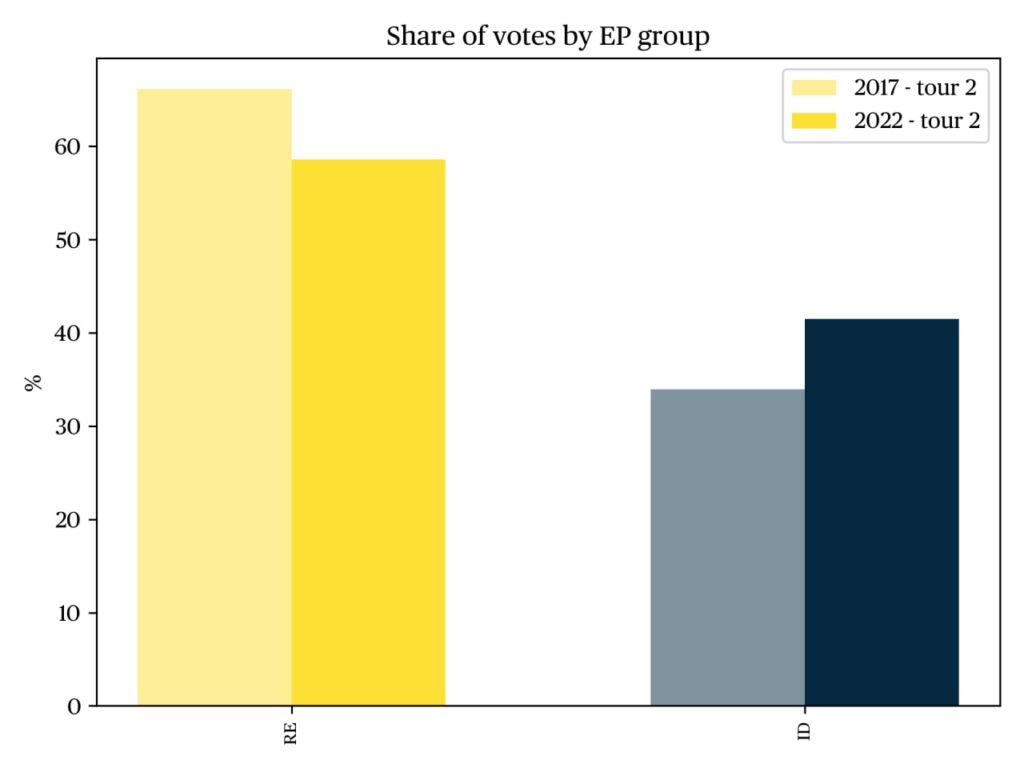

In the same time, the votes were also dispersed among these three candidates, none of whom, including the incumbent who was clearly in the lead, really managed to dominate the election. The presence in the second round of voting of the same two candidates who had already qualified in 2017 made the second round appear once again as a “barrage” against the extreme right; this lack of novelty, together with the high likelihood of Macron’s victory despite polls predicting a close outcome, had a demobilizing effect on the electorate between the two rounds of voting. In the end, Macron’s victory was not very close in relative terms (58.5% of the vote) but his advantage narrowed dramatically compared to 2017, as the number of votes separating the candidates decreased by almost half (from 10 to 5.5 million votes). Support for the incumbent president also shrunk in terms of registered voters, insofar as abstention had, as in 2017, increased between the two rounds (+ 2.7 points), reaching its second-highest level under the Fifth Republic, at 28.01%. This decrease in turnout, together with the historically high number of blank and invalid ballots, led to over one third (34.2%) of registered voters not expressing any preference in the second round. The President of the Republic was thus chosen by 38.5% of registered voters in 2022, down from 43.5% in 2017.

The legislative election of June 2022 was also marked by voter disaffection. While voter turnout in legislative elections has always been lower than in presidential elections, it has been continuously declining since the 2000s. Turnout rates, which were close to 80% from 1967 to 1986, fell below 70% in 1988; from 2002 onward, participation decreased even further, falling below 60% in 2012 and below 50% in 2017. The institutional reforms that introduced a five-year presidential term and inverted the order of the presidential and legislative ballots are deemed to have accentuated the trend toward differential mobilization by promoting a perception of legislative elections as subordinate to the presidential elections: as both official and informal mobilization mechanisms became less effective, the legislative elections came to be perceived as devoid of any autonomous political significance or impact, discouraging the least politicized citizens to turn out to vote.

In 2022, owing in part to the active politicization strategy implemented by Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the legislative elections benefited from a degree of attention uncommon since the beginning of the century. The left-wing political leader had called on the French to “elect him Prime Minister,” placing its hopes in some genuinely parliamentary features of the Fifth Republic, in which cabinets must rely on a majority in the National Assembly to govern. At 52.5% in the first round and 53.8% in the second round, abstention was nevertheless very high, confirming that France is caught in a cycle of very low electoral mobilization, marked by patterns of increasingly intermittent participation (which concern more than half of registered voters), a detached attitude towards electoral processes, a regression of traditional mechanisms of transmission of civic habits, the weakening of moral incentives to vote, and a reinforcement of the feeling that voting is useless.

Social and territorial patterns of electoral behavior

While abstention in the presidential election was more moderate and affected all categories of voters, the sharp increase in abstention in the legislative election that took place two months later was socially differentiated, particularly according to age and socio-economic characteristics. Not only does turnout always increase with age, but the decrease in participation between the presidential and legislative elections was also much more pronounced among those under 35 than among those over 60, leading to retirees being over-represented among those who turned out to vote in the legislative election. Similarly, the differences in turnout widen considerably between blue-collar and white-collar workers on the one hand, and managers on the other, or according to income or educational attainment level. The spatial distribution of abstention is consistent with its social determinants: abstention is particularly common in the deindustrialized areas of Northern and Eastern France, in working-class suburbs, and in the suburbs of the Rhône and Mediterranean regions, with differences of several dozen percentage points (up to 40) between working-class and middle-class polling stations.

The same factors that influence voter turnout also affect the choice of a candidate. Thus, Macron is preferred by the youngest (under 25) and oldest (over 65) voters, while Le Pen wins among working class voters between 30 and 50; the social and professional profile of the two candidates’ electorates is also radically different: while three out of four managers choose Macron, Le Pen is clearly in the lead among workers and employees. Social determinants exhibit consistent patterns, with the share of Macron votes increasing as education and income rise.

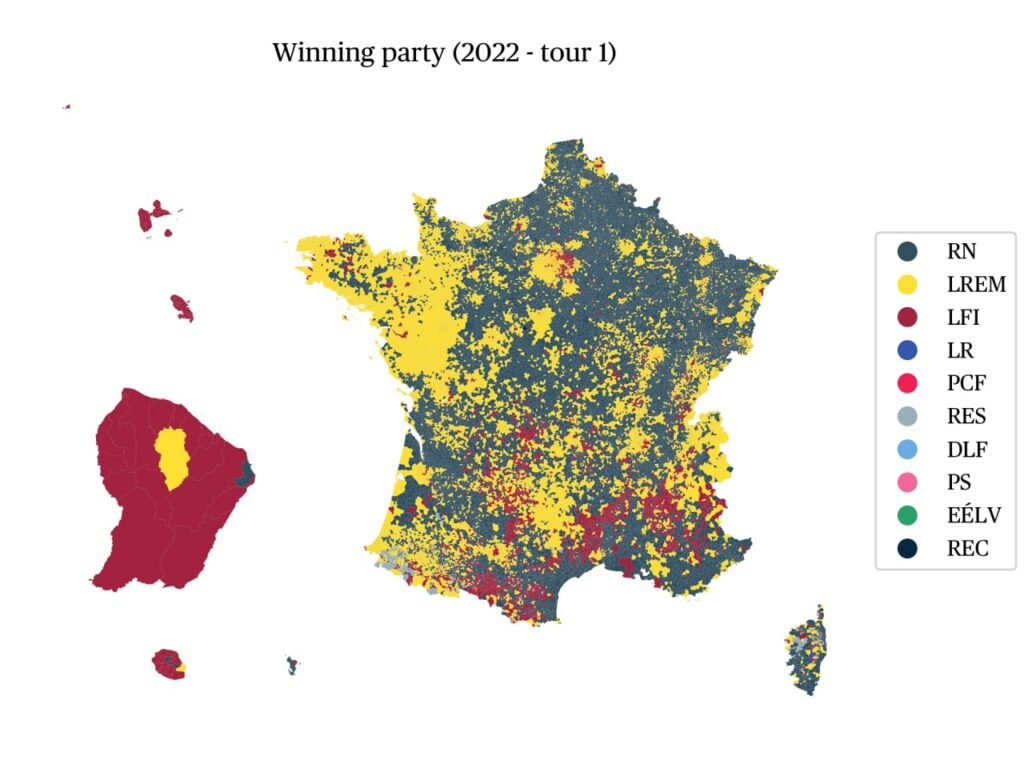

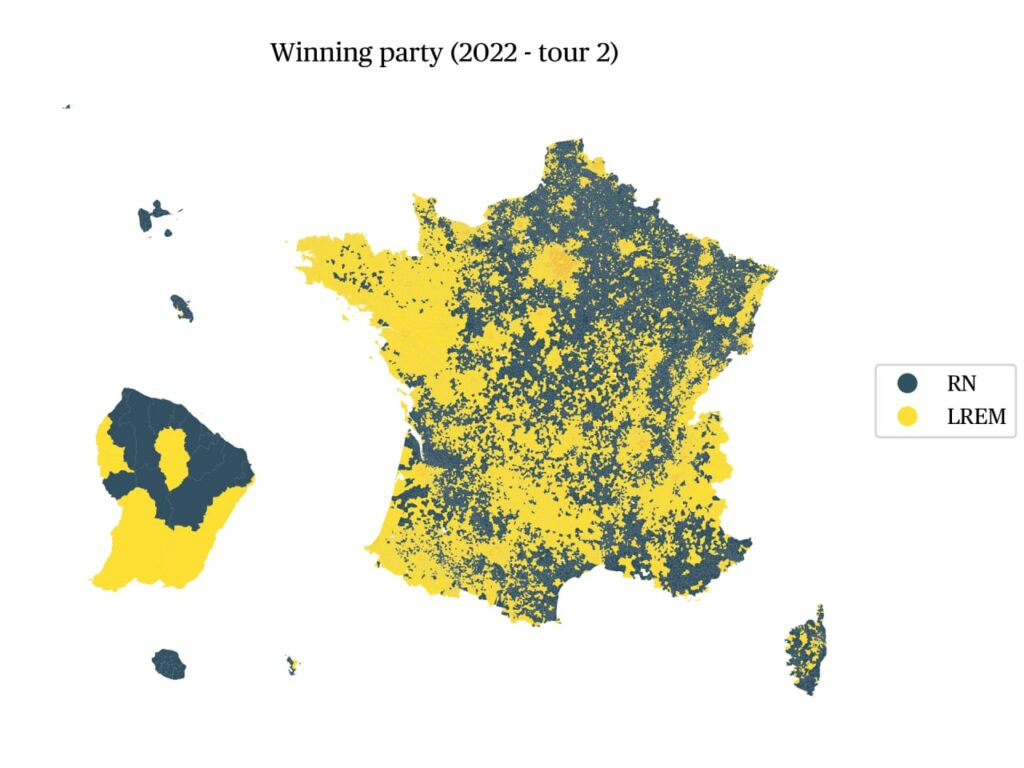

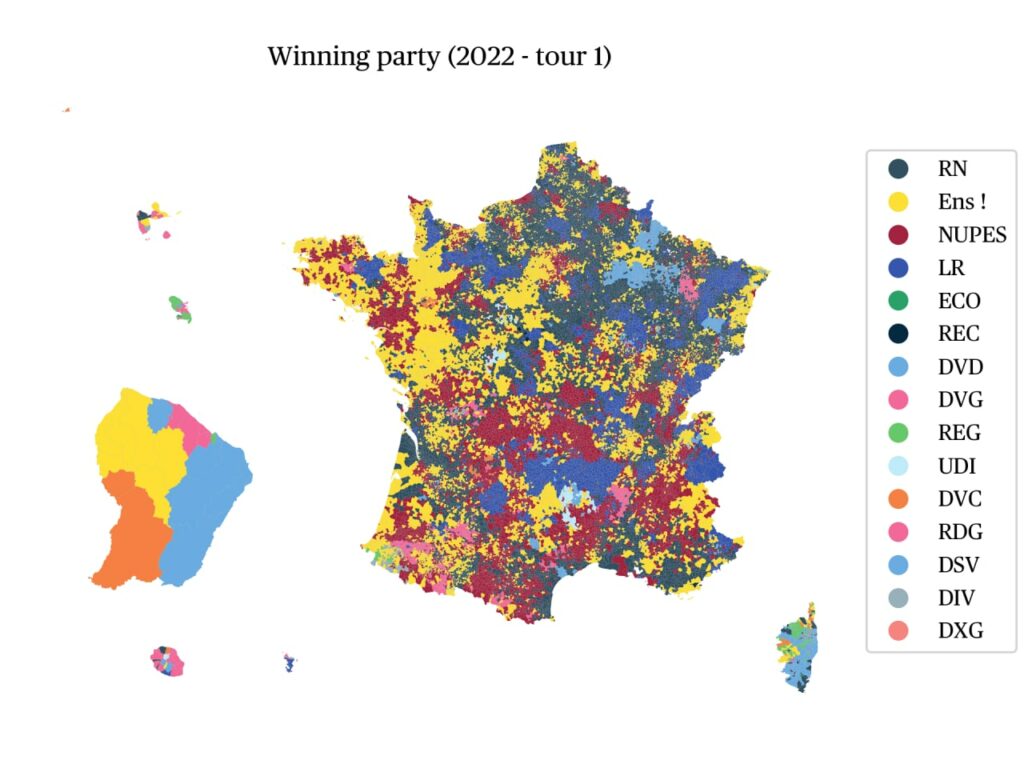

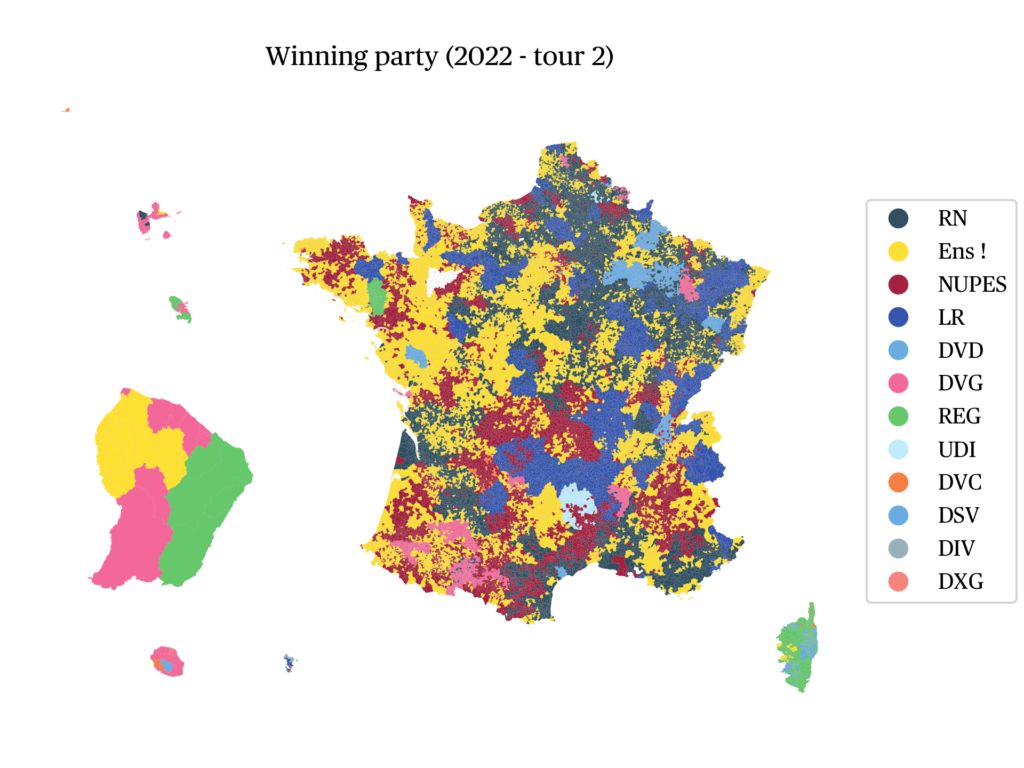

Looking at maps of election winners in the second round of the presidential election in 2017 and in 2022, the increase in the number of communes where Le Pen was leading is blatant. The RN is deepening and broadening its presence in its traditional strongholds of Northern, North-Eastern and Mediterranean France, but its penetration in the Garonne and Rhône valleys is also very significant. While its successes remain unevenly distributed, the areas in which the RN has not made any inroads are now much rarer: even in Brittany, a region traditionally hostile to the RN, in a few municipalities voters gave more votes to Marine Le Pen than to Emmanuel Macron in the second round. At the same time, the spatial distribution of the RN’s gains also provides insights into the geography of Macron’s core electorate. A clear preference for Macron is expressed in the West (especially in Pays de la Loire, Brittany, Normandy, Basque Country and Bearn), as well as in Ile-de-France (which is beginning to constitute an isolate in the northern half of the country), and, more generally, in the metropolises where the outgoing president always won in the second round, including in Eastern and Southeastern France, where the RN vote is more widespread; Lille in Northern France, Marseille and Montpellier on the Mediterranean coast constitute enclaves of Macron vote in areas quite clearly dominated by the RN.

However, the political behavior observed in 2022 cannot be explained only by the urban-rural divide. While curves correlating the density of communes with the candidates’ results show almost inverse trends for right-wing and left-wing candidates, a higher degree of urbanization generally proves favorable to the left-wing and ecologist candidates, but also, very clearly, to Macron, while the RN thrives more in small communes and towns, especially in suburban areas.

It should be remembered that, since electoral behavior is socially anchored, territorial variations also reflect differences in the spatial distribution of social characteristics (e.g., higher education).

At the same time, the success of LFI in municipalities with a population of 2,000-5,000 inhabitants testify to the existence of a strong rural left, which appears on the map of the first round of 2022 in the southern edges of the Massif Central or in the department of Drôme. However, in both rounds, vast rural areas, many of them located in Western France, voted even more massively for Macron than in 2017, as some former Les Républicains (LR) supporters embraced Macron’s candidacy. The outgoing president also achieved good results in medium-sized cities (over 20,000 inhabitants), while the LR candidates obtained better results in small towns of 5,000-15,000 inhabitants. But while Macron achieved better results in the largest cities, he can hardly claim to be the sole “candidate of the metropolises,” since Mélenchon has often been on a par with him in these areas. LFI, for its part, achieved some of its best results in working-class suburban municipalities, winning, in particular, in all of the 12 constituencies of Seine-Saint-Denis. These successes are certainly to be relativized given the high abstention rates (over 65%) that affected these areas; however, it can also be emphasized that these results were achieved despite a marked trend towards abstention among the categories of voters that make up LFI’s core electorate.

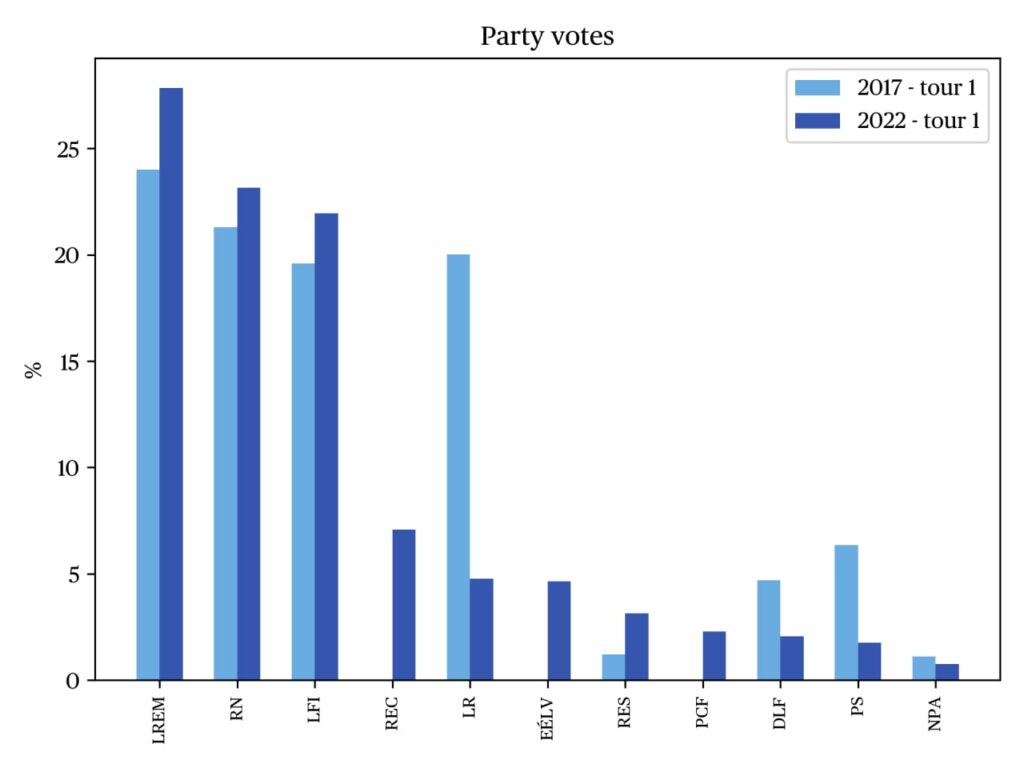

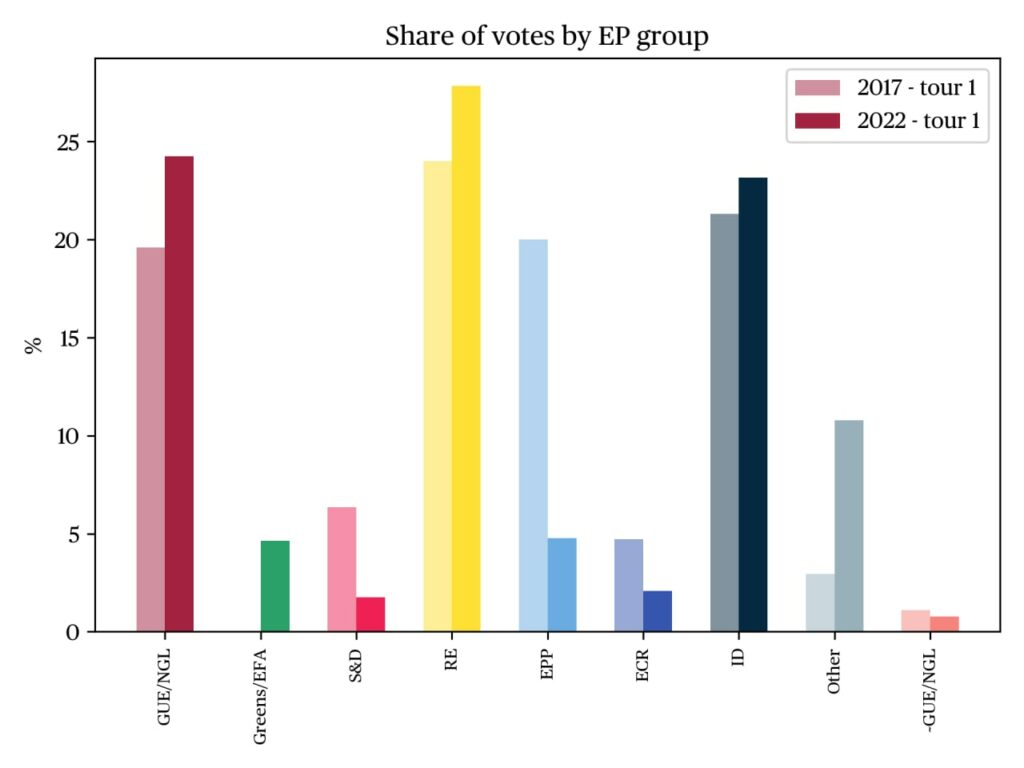

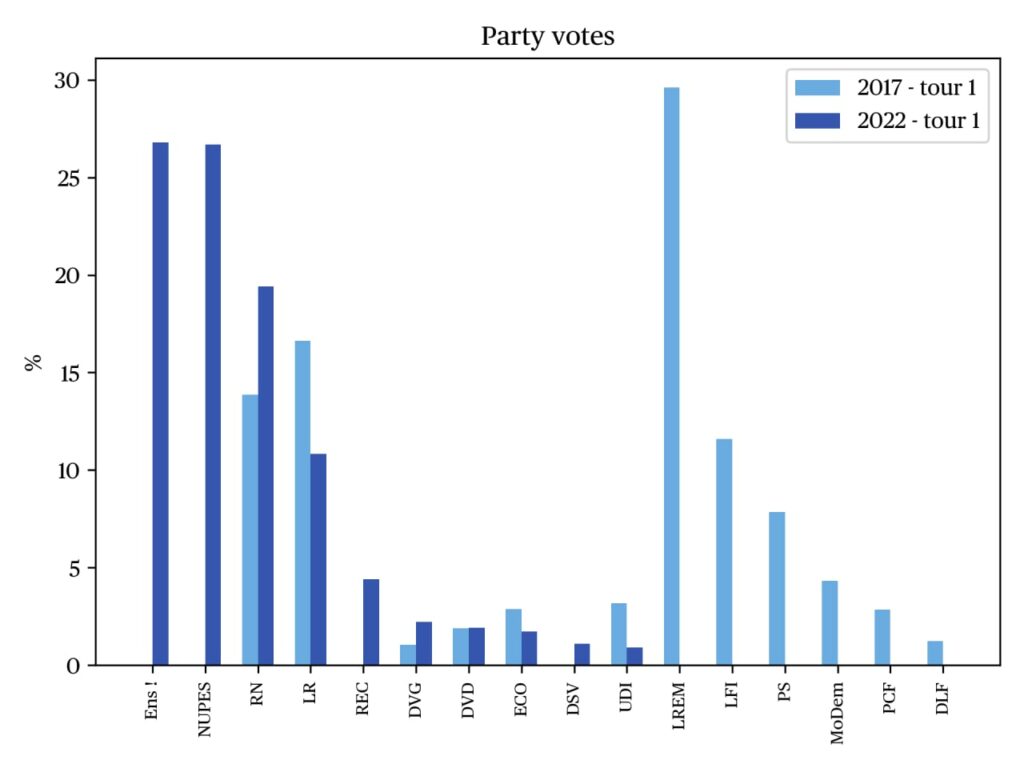

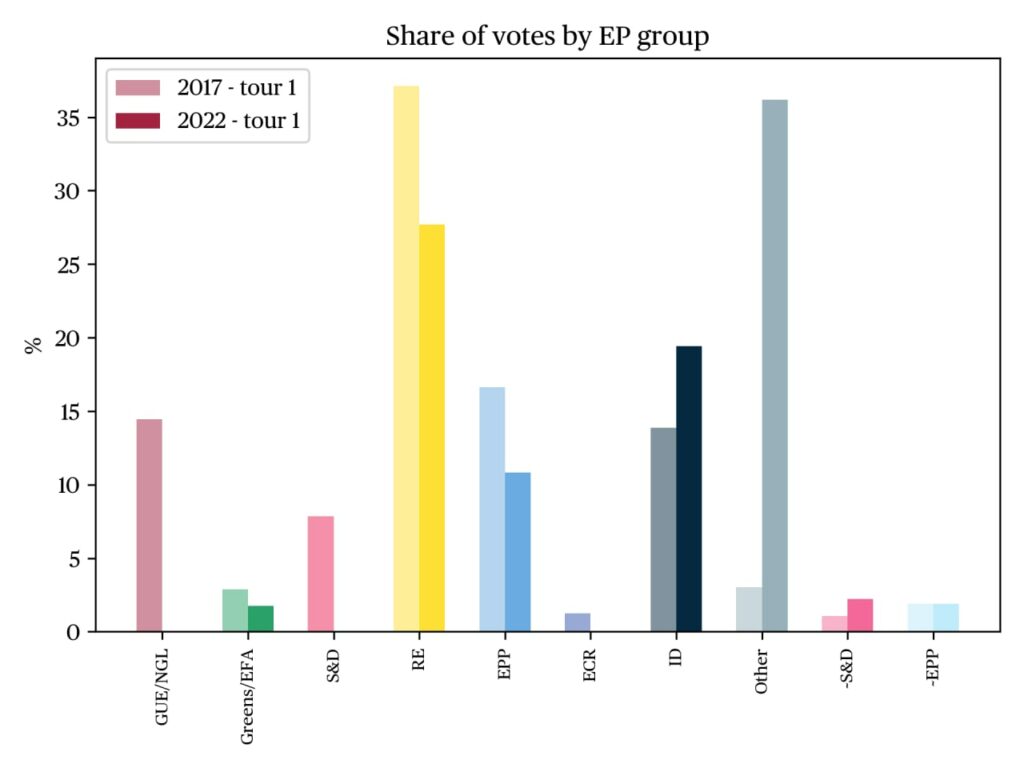

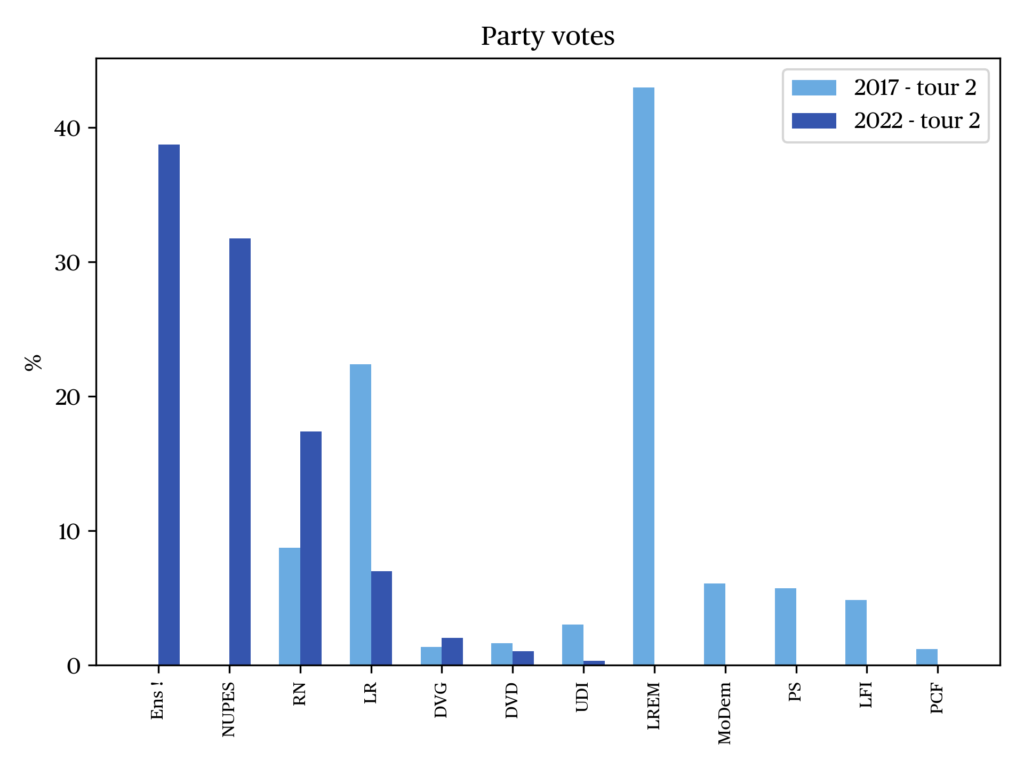

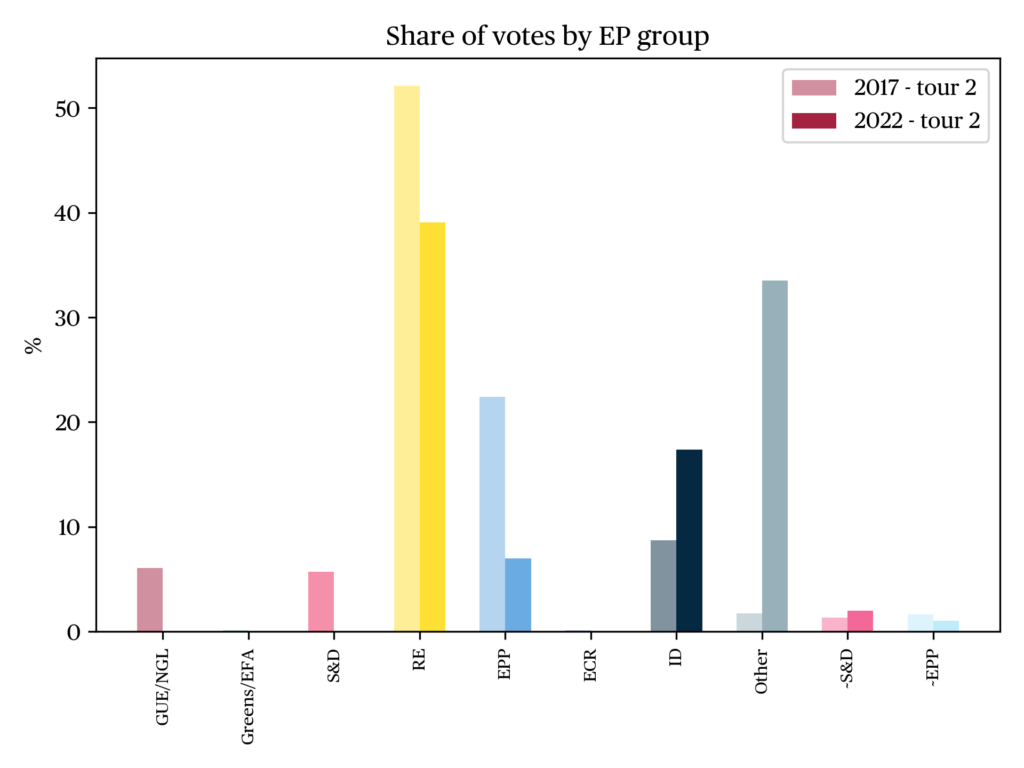

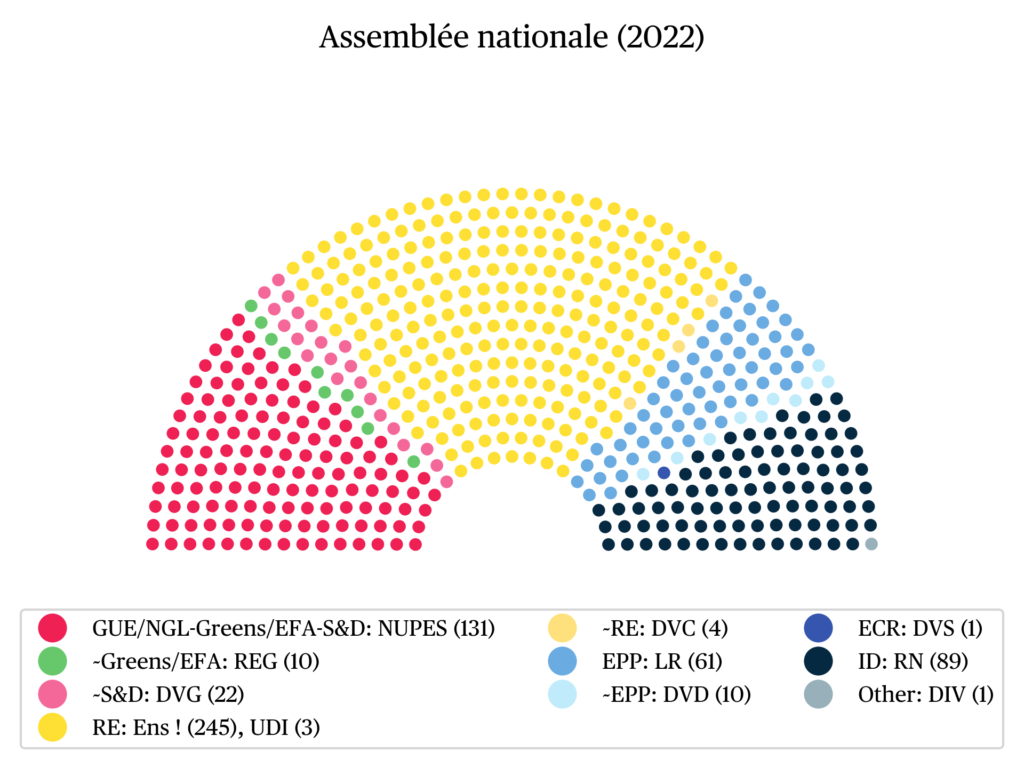

Despite the failure of a reform project that was supposed to introduce proportional representation for a fraction of the National Assembly’s seats, the voters who turned out for the legislative election eventually elected a hung parliament, in which opposition groups on the right and the left have become stronger. While opposition parties probably lack the capacity to impose their political line (all the more so since these parties seem difficult to coordinate), the composition of the parliament now more accurately reflects the country’s political mosaic and will most certainly enhance the importance of parliamentary work. The high abstention rate needs to be taken into account when analyzing the results of the legislative election. Segments of the electorate most favorable to Macron (over-65-year-olds, graduates) are also the most assiduous at the polls; conversely, the strong demobilization of young and working-class voters has penalized the left (which, despite this differential abstention, tied in the first round with Macron’s coalition). The RN was also affected by a loss of momentum in the legislative election, although less strongly than in previous elections, and benefited from increased legitimacy in some territories (as Benoît Coquard has shown, in some areas, the RN vote can now serve as a respectability marker) as well as from a greater presence among active middle classes less inclined to withdraw from voting. Finally, the fact that the re-elected president has obtained only a plurality of seats in the National Assembly can be understood as the result of the demobilization of part of his electorate, which is suggested by the increase in abstention in the legislative elections in the strongholds of electoral Macronism, particularly in the West. With about 25 per cent of the vote in the first round, the Ensemble electoral coalition achieved — by far — the lowest result of any presidential coalition since 2002. Thus, despite the sociological sources of differential abstention traditionally being more favorable to the parties of the center and the right, the electoral base of the outgoing president proved insufficiently solid to guarantee him a majority, while, in spite of their electorates being more inclined to demobilization, the two main opposition forces held up rather better.

A still ongoing political reconfiguration

In the context of the ongoing reconfiguration of the French party system, intense struggles are taking place between, and just as much within, the three blocs that emerged in the first round of the presidential election (as we have seen, a rigorous description of the political landscape should require at least a mention a fourth “bloc,” that of non-voters). As an unprecedented political period begins (for the first time since the introduction of five-year presidential terms, a president is serving a second term without a parliamentary majority), the reconstruction of the party system is far from stabilized.

The major historical parties, LR and Parti socialiste, who had been eliminated in the first round in 2017, have experienced even harsher defeats in 2022, with their respective candidates not even managing to reach 5%. However, during the territorial elections of the last legislative period, these two parties have shown some resilience and demonstrated strong local presence, as if a scalar differentiation of political organizations was emerging, with different parties dominating at different institutional levels.

More than ever, the electorates resemble, as Patrick Lehingue often reminds us, diversified and more or less stable conglomerates much more than homogeneous and consolidated blocs. The NUPES alliance has demonstrated its electoral effectiveness in implementing a “useful vote” strategy on the left via single candidacies (a strategy which had already boosted Mélenchon’s candidacy in the days leading to the first presidential round) without, however, resolving all the programmatic or strategic divisions between its constituent parties. In the same way, the presidential party, now largely identified with the center-right, is confronted with the challenge of its institutionalization after the programmed departure of its founder. However, Macronism has not yet established itself as a very clear political doctrine, and the President’s centrist party is competing with other organizations, some of which claim a similar position on the political spectrum while others seek, on the contrary, to reactivate the right-left divide. While Macron had won in 2017 with the support of a majority of voters coming from the left, his electoral base has since then significantly shifted to the right, which had already been attested to by the alliances concluded during the municipal elections of 2020, and has now been confirmed by the movement of LR voters towards the outgoing president.

The RN, for its part, has emerged stronger from these ballots. Its candidate once again reached the second round of the presidential election. She lost again, but gained almost 3 million votes in the process. With 89 MPs, her party can now compete with the NUPES for the title of leading opposition group. The RN’s presence has also consolidated in a growing number of territories, where it has undergone a process of electoral normalization that has proved successful in large segments of electorate, reaching beyond traditional protest audiences.

Finally, we observe that the popular prediction that French political parties were in decline has hardly come true. Parties continue to structure French political life, as attested by the creation of Renaissance: even Emmanuel Macron, who had originally claimed that he wanted to build a movement, but not a party, has know engaged in an enterprise of partisan consolidation.

Nevertheless, the party system continues to undergo changes and mutations, which at this stage have hardly produced any democratic re-enchantment among citizens. The 2022 national election sequence indeed shows that the French electorate’s relationship to political parties is distant and strongly polarized, especially from a generational and social point of view. While the new National Assembly elected in June 2022 has seen a relative diversification of its MPs in terms of social and professional backgrounds, the revitalization of representative democracy appears more than ever as a crucial issue.

citer l'article

Anne-France Taiclet, Presidential and legislative elections in France, April-June 2022, Oct 2022,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue