Presidential and parliamentary election in Türkiye, May 2023

Ali Çarkoğlu

Professor in Political Science and Dean of the School of Administrative and Social Sciences at Koç UniversityIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Ali Çarkoğlu

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

On May 14, 2023, elections were held in Turkey to elect both the Grand National Assembly (Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi, TBMM) and the President of the Republic of Türkiye. As no candidate had won a majority in the first round of the presidential election, a second round was held on May 28. The incumbent president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and the leader of the main opposition party, Kemal Kılıçtaroğlu, advanced to the second round. Ultimately, Erdoğan won the second round by a margin of 2.33 million votes and was elected for a third presidential term.

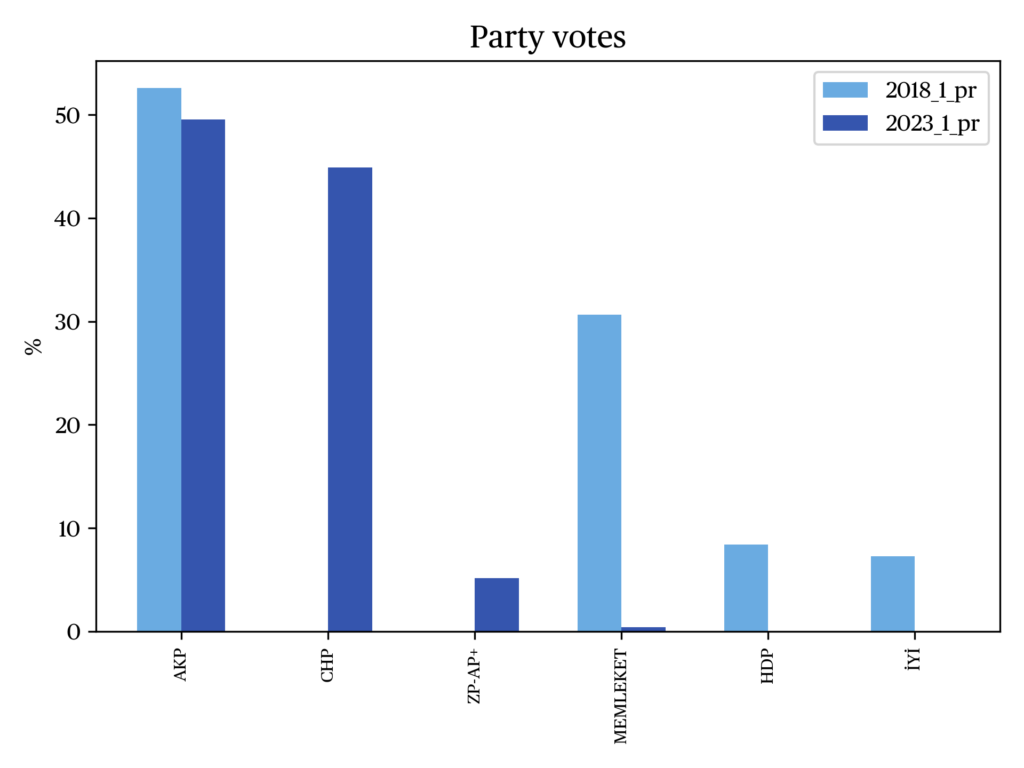

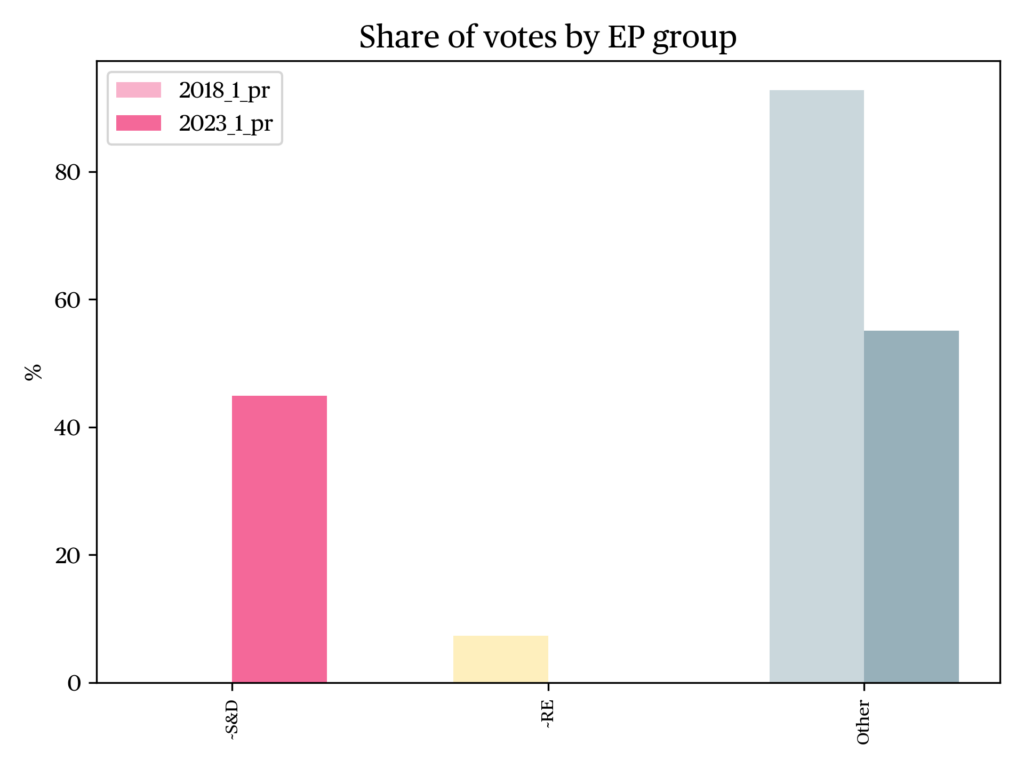

Since the 2018 election, President Erdoğan’s People’s Alliance had expanded by absorbing minor political parties such as the New Welfare Party (Yeniden Refah Partisi, YRP). The Free Cause Party (Hür Dava Partisi, HÜDAPAR) and the Democratic Left Party (Demokratik Sol Parti, DSP) also joined the alliance backing Erdoğan’s candidacy. Although the incumbent People’s Alliance saw a decline of about three percentage points for the TBMM election, it still secured the majority of seats that will allow it to control the legislative agenda during the next term.

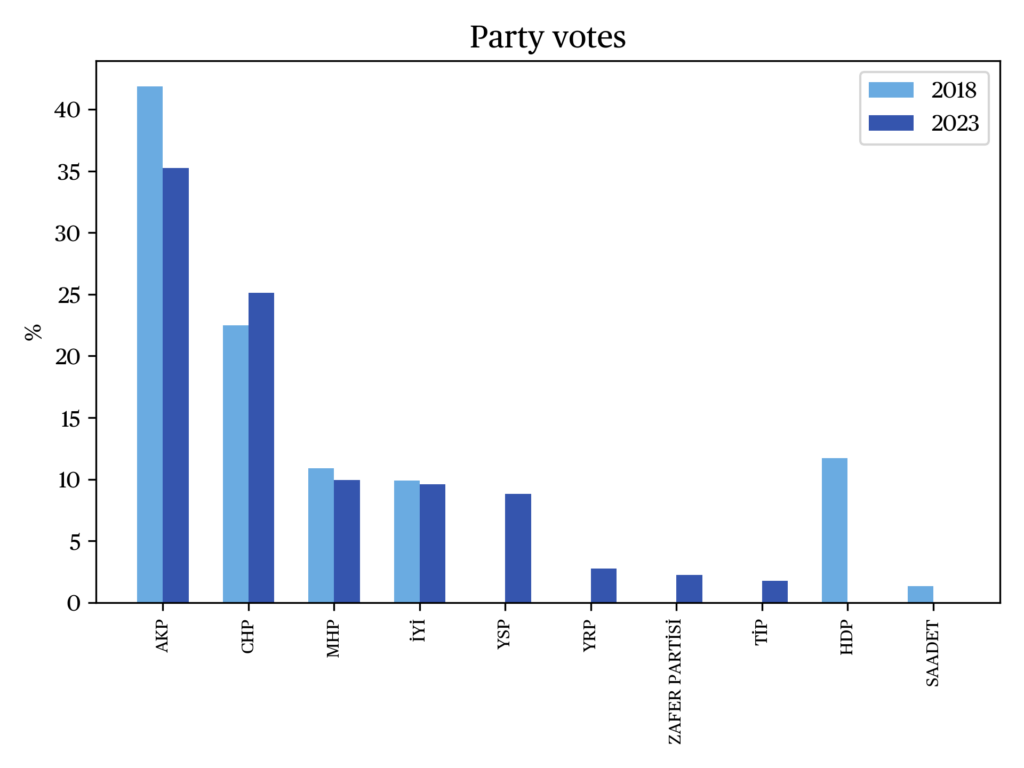

A solidified and enhanced People’s Alliance characterized by a consistently right-of-center, conservative, and pro-Islamist ideology, garnered a narrow victory in both general elections. The founding members and largest parties in the alliance, the Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP) and the Nationalist Action Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi, MHP), experienced a decline in support by 6.94 and 1.03 percentage points, respectively, leading to an overall loss of 21 seats in the TBMM. Consequently, the new system that brought Erdoğan to the presidency was reinforced, precluding the return to a strengthened parliamentary system advocated by the opposition. Moreover, the original AKP positions were pushed towards the fringes of nationalist and pro-Islamist agendas. Economic policy, in particular, suffered from a politically motivated monetary policy that aimed at maintaining low interest rates but eventually resulted in a sharp increase in exchange rates and economic imbalances.

Turkey’s Political and Electoral System in a nutshell

The current Turkish presidential system was established through a series of political and constitutional reforms, which can be traced back to the early 2000s 1 . In 2002, Erdoğan and the AKP came to power in the parliamentary election, with Erdoğan becoming Prime Minister in 2003. During his tenure, Turkey experienced significant economic growth and political stability. However, the secularist establishment in the TBMM impeded the election of AKP’s Abdullah Gül as president in 2007. As a result, the AKP government called snap TBMM elections after which AKP support grew, eventually allowing for Gül’s election. Subsequently, the AKP also moved for a set of constitutional amendments, including changes that allowed for the direct election of the president.

The 2007 constitutional amendments paved the way for the public to directly elect the president, a provision that took effect with the presidential election held in August 2014, which saw Erdoğan becoming the first popularly elected president. A new presidential system with stronger executive powers was established through the April 2017 referendum, held under a state of emergency declared following a failed military coup in July 2016. The state of emergency was only lifted after the presidential and TBMM elections of June 2018, necessitating the formation of the People’s Alliance to ensure a comfortable majority to the AKP in the TBMM.

To be elected, a candidate for President of Turkey must receive at least 50% of the valid votes. If this is not achieved, a runoff election is held between the top two candidates. Candidates must be at least 40 years old and hold a university degree. To nominate candidates, political parties must have received at least 5% of the vote or be part of an alliance that collectively surpasses this threshold. Self-nominated candidates must gather at least 100,000 signatures.

The TBMM elections use the D’Hondt method of proportional representation, with a minimum vote threshold applied nationwide. The first electoral threshold was introduced in 1983 by the military regime and was set at 10% of valid votes. This threshold was reduced to 7% by a recent amendment published in the Official Gazette on April 6, 2022. Unlike in the 2018 election, parties in alliances cannot divide alliance votes to secure seats, as this option was eliminated in the 2022 reform.

Before the latest reform, parliamentary seats in a province or electoral district were primarily distributed based on alliance and independent party votes. The number of seats for each alliance was determined first, followed by the distribution of parliament members to each party based on their vote shares within the alliance. This gave an advantage to parties in an alliance, leading to scenarios where a party could secure seats even if their votes were less than an independent third party’s. Since the reform, the votes obtained by the parties that surpass the threshold are directly and collectively considered in a single step. If political parties capable of garnering votes from diverse voter blocs come together to form an alliance and choose to run on a single list (typically led by the party that receives the highest votes nationwide), rather than individually, each of them can have the opportunity to be represented in the parliament with more candidates.

However, an important additional condition must be fulfilled in order for that strategy to be effective: voters must be convinced to vote for the party leading the alliance in lieu of their own parties. For example, a voter affiliated with the Democratic Party (Demokrat Parti, DP), the Democracy and Progress Party (Demokrasi ve Atılım Partisi, DEVA), or the Future Party (Gelecek Partisi, GP) does not see their party logo on the ballot because the candidates of these parties participate in the election on the list of the CHP, representing the Nation Alliance. Therefore, these voters must vote for the CHP list to support their party’s candidates.

In electoral districts where alliances run multiple lists, it becomes harder for the alliance to win a seat with a narrow vote difference. Parties within the alliance competing against each other can weaken the overall coalition. For example, in many districts, the Green Left Party (Yeşil Sol Parti, YSP) and the Workers’ Party of Turkey (Türkiye İşçi Partisi, TIP) competed against each other even though they were part of the same alliance. When TİP’s votes were added to the alliance list, they could secure a seat, but entering separately with a slightly lower vote share might result in neither party winning a seat. This can weaken the alliance and its constituent parties.

As for the Nation Alliance, where ideologically distant partners are part of the same alliance, CHP voters might not feel comfortable voting for DEVA, Future, or SP candidates. This can weaken the electoral base of the Nation Alliance. However, prominent alliance members such as the MHP, YRP, and BBP ran on separate party lists rather than the AKP’s. This appears to have favored the People’s Alliance over the Nation’s Alliance.

Main Campaign Issues and the Results of the May 14 Ballots

Soon after the 2018 elections, expectations of an early election in the country rose. These expectations were further strengthened by the economic crisis that began in 2018 and saw a rapid decrease in the Turkish lira’s exchange rate against the US dollar. In Turkey, inflation, which was 20.3% in 2018, reached 64% by 2022.

The 2019 local elections contributed to these expectations as the incumbent People’s Alliance lost major metropolitan centers, including Istanbul and Ankara, which have remained in conservative control since the mid-1990s. In addition, the main opposition party. the CHP and independent candidates won in all Thrace, Aegean, and Mediterranean coastal municipalities, except in Balıkesir. Although the Alliance still had a dominant electoral appeal, with slightly more than 50% of the votes in the country for municipal council and mayoral elections, control of the largest metropolitan centers, except in Bursa, was lost. With the economic crisis continuing to erode the People’s Alliance support base, an early election was expected to be called before the full negative impact of the crisis took effect. Even though the Turkish economy had a strong COVID-19 pandemic recovery, that growth did not last. The economy grew by 5.6% in 2022, down from 11.4% in the previous year, as exports, investment, and manufacturing activities lost momentum. Due to the deteriorating external environment and heterodox monetary policies, the economy began to slow down. The Turkish lira lost 30% of its value by 2022 despite an estimated $108 billion in indirect forex interventions by the central bank 2 .

On February 6, 2023, two massive earthquakes devastated 11 provinces, affecting 16.4% of the population and 9.4% of the economy. “Direct losses are estimated at $34.2 billion, but the reconstruction needs could be double. The earthquakes added pressures to an increasingly fragile macro-financial situation.” However, the World Bank also noted that pre-election spending and reconstruction efforts should contribute to growth, which is expected to surpass 3% by 2023 3 . In short, economic difficulties remained high on the agenda. However, as the election day approached after the twin earthquakes, the incumbent Erdoğan administration imposed its control over the reconstruction efforts and re-established its credibility by providing economic relief.

The competition for leadership within the opposition attracted as much attention as the economic crisis the country was moving through and the challenges of earthquakes. Identifying the opposition’s future presidential candidate proved a more difficult task than anticipated. Negotiations for the alliance’s presidential candidate collapsed a month after the earthquake. The Good Party (İyi Parti, IYIP), the second-largest party in the alliance, expressed frustration with selecting a winning candidate for the upcoming presidential election. They argued that CHP leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu could not secure the presidency if nominated as the alliance’s candidate. The IYIP suggested finding an alternative candidate and discussing the names of Istanbul and Ankara’s metropolitan mayors. However, both mayors were CHP members and hesitant to challenge their party leader for the candidacy.

In the first round of the presidential election, the incumbent President Erdoğan and the Nation Alliance candidate Kılıçdaroğlu faced competition from two additional candidates, Muharrem İnce and Sinan Oğan. İnce’s campaign targeted the opposition instead of the incumbent alliance, but he withdrew from the race amid allegations concerning his wealth and personal life. Oğan was initially part of the Ancestral Alliance, a group of national-conservative parties that included the Victory Party and the Justice Party. He received the third largest vote share in the first round and eventually supported Erdoğan in the second round, leading to the dissolution of the Ancestral Alliance. The divided opposition’s infighting during the election contributed to the People’s Alliance and Erdoğan’s victory.

Turnout, TBMM Elections, and the First Round of the Presidential Election

For the May 14 elections, there were 60.7 million registered voters within the country and 3.4 million registered voters outside. 4.9 million voters were first-time voters. 20.8 million were below the age of 35 and 5.2 million were above 70 years of age. Hence, the voting-age population was predominantly composed of younger voters.

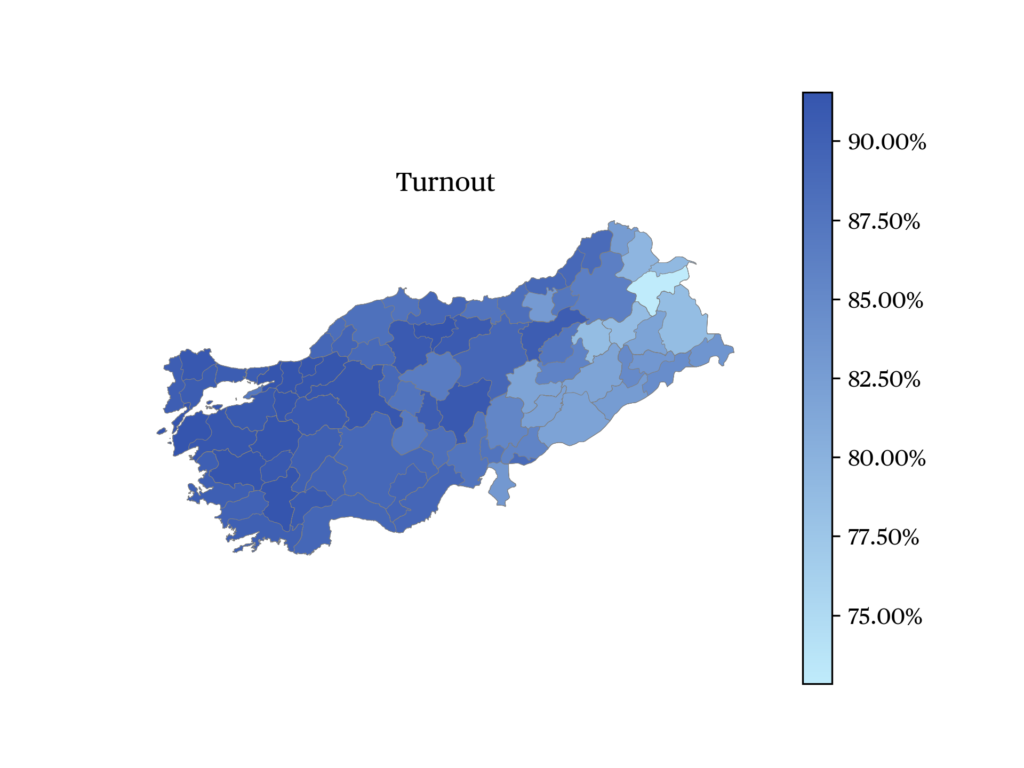

The turnout in the first round of the presidential election was 87.04%, while only 49.4% of those registered outside the country cast votes. While outside the country, there is little gender difference across different age groups, domestically, the turnout of women below the age of 65 was 2-6 percentage points higher than that of men. In contrast, male turnout was approximately 8 percentage points higher in the 65+ group 4 . The geography of turnout is illustrated in Figure a. Turnout was significantly higher in the western provinces. However, typically more than 70% of eligible voters cast a vote even in the far-eastern provinces, where turnout was lowest. Considering the fact that the predominantly Kurdish voters of East and Southeast Anatolia lived in the lowest-turnout regions of the country, one could speculate that if turnout in these regions had been higher, this would have favored the opposition parties and their presidential candidate Kılıçdaroğlu.

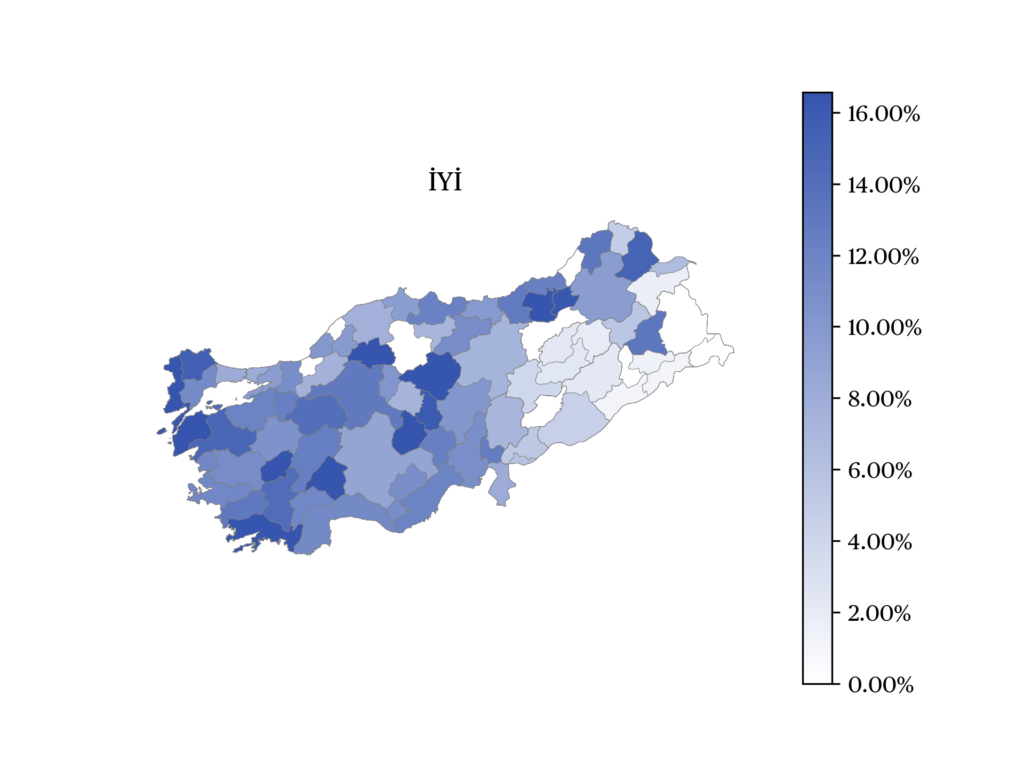

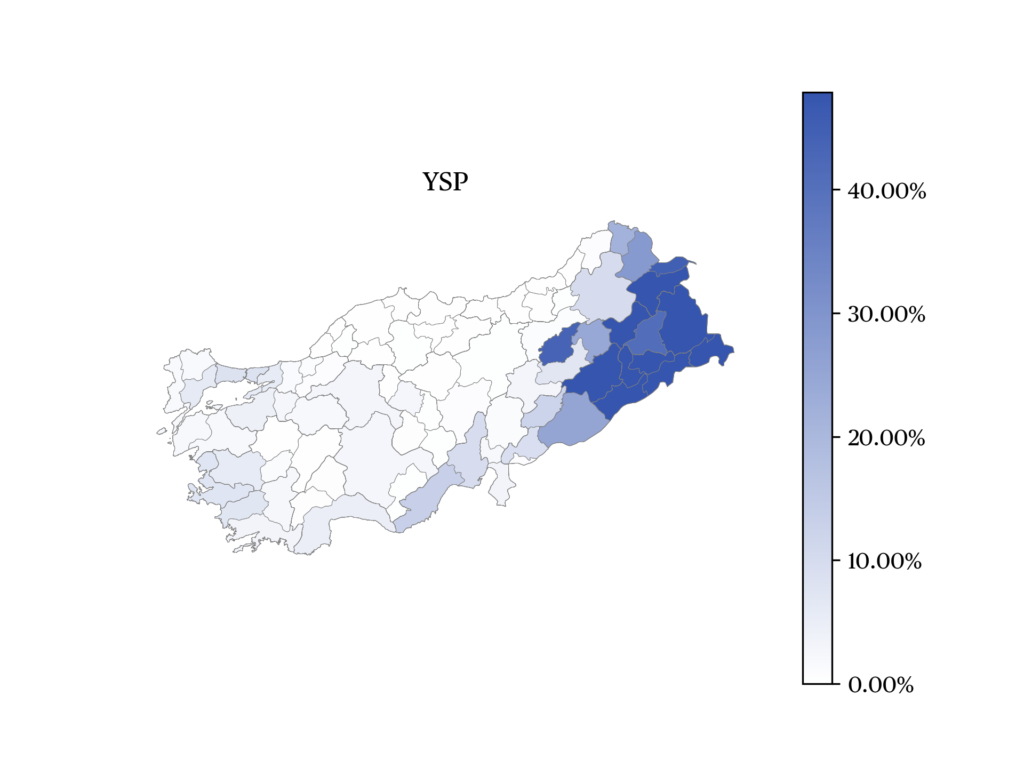

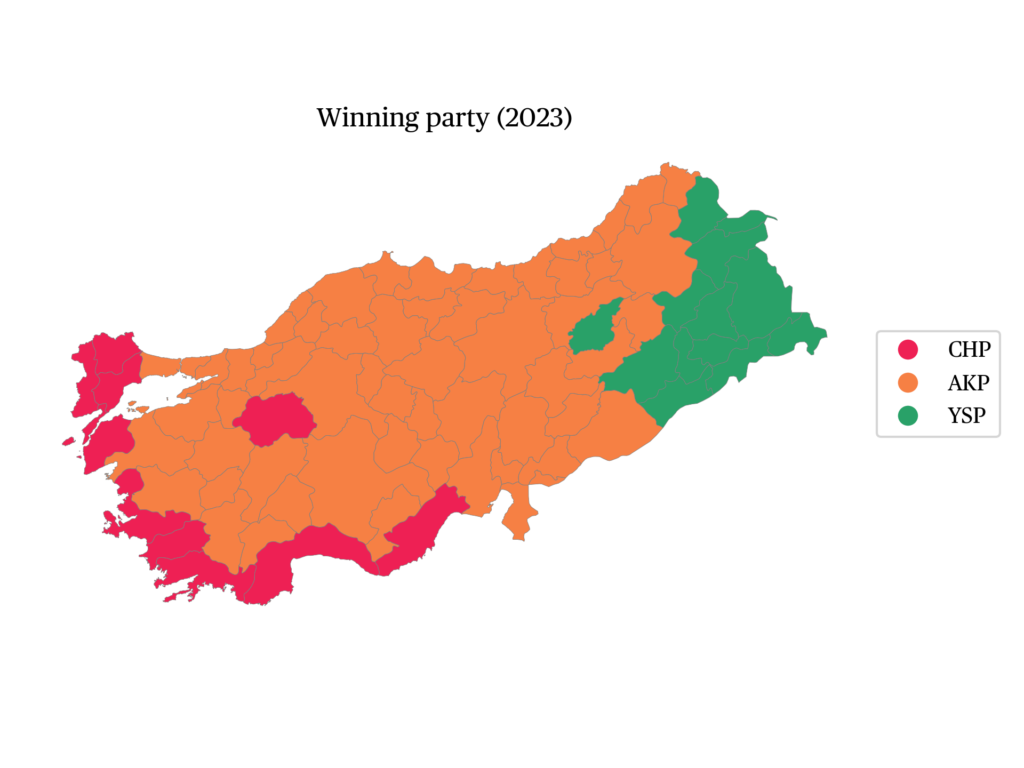

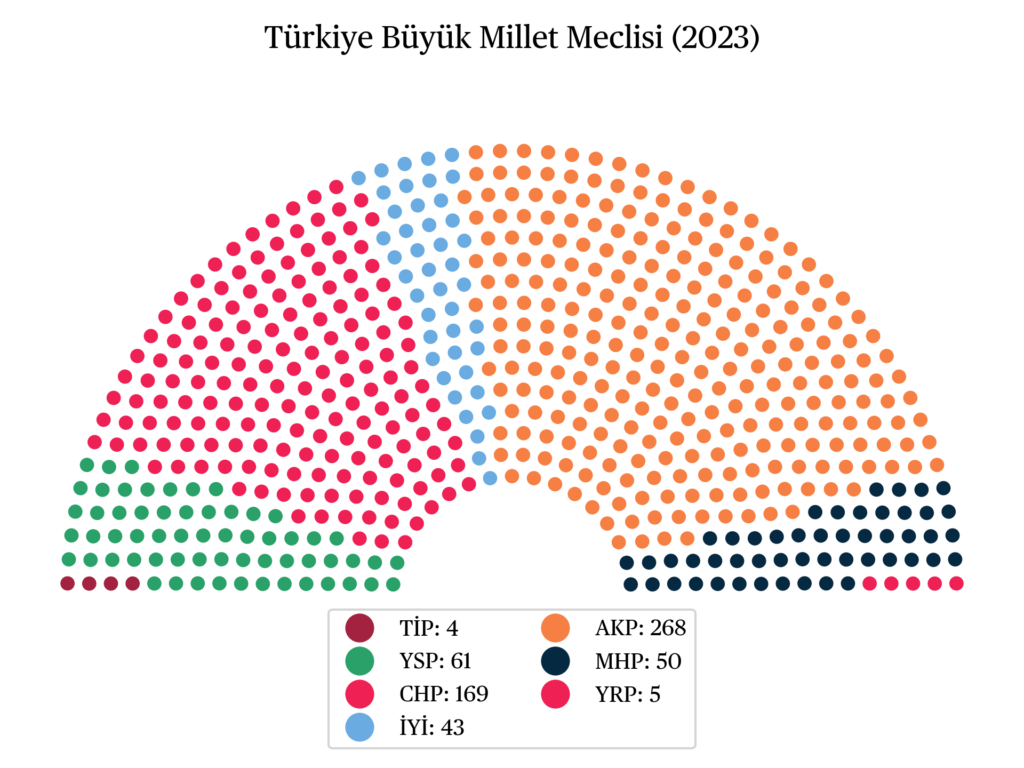

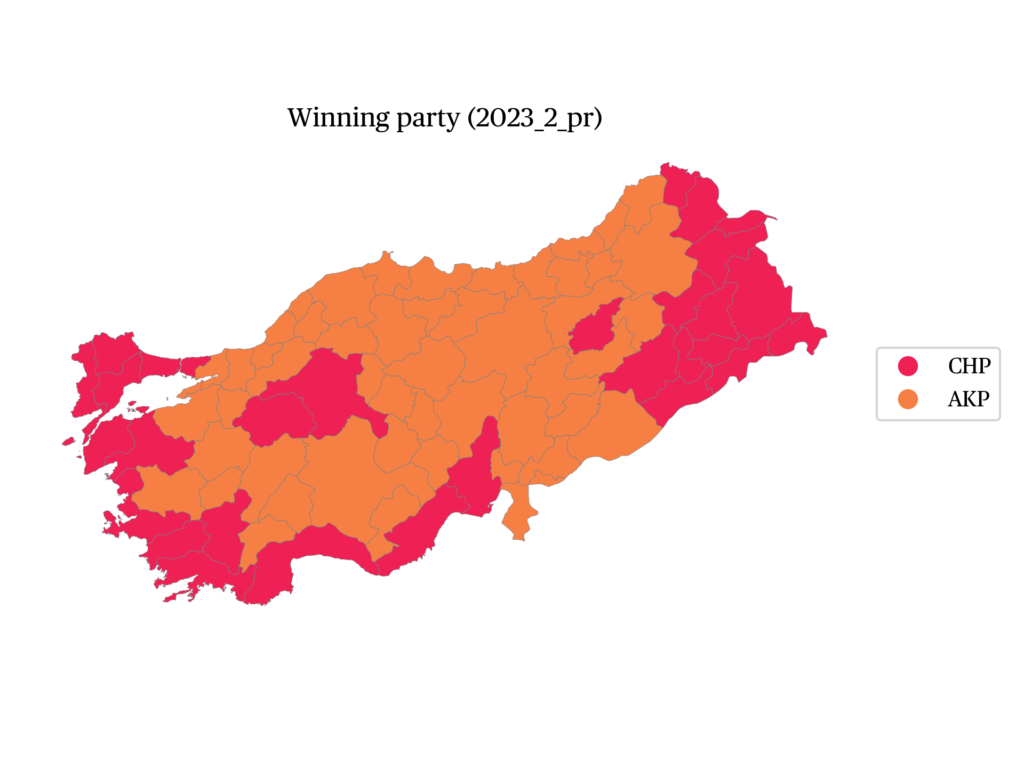

Erdoğan was 264,176 votes short of winning in the first round, obtaining a total of 49,52% of the votes. Kılıçdaroğlu obtained 2,538,671 votes less than Erdoğan, or 44.88% of the valid votes. For the TBMM, 24 out of the 36 eligible parties competed in the election. The AKP obtained 35.6% (268 seats), the CHP 25.4% (169 seats) of valid votes. The AKP contingent in the TBMM shrunk by 27 seats, while the CHP group including other Nation Alliance candidates expanded by 23 seats. Among nationalist parties within the People’s Alliance, the MHP obtained 10.1% (winning 50 seats) and the Grand Unity Party (Büyük Birlik Partisi, BBP) 1% of the votes. The pro-Islamist partner of the People’s Alliance, the YRP, gathered 2.8% (winning five seats). Hence, the total vote share of the People’s Alliance is 49.5% (winning 323 seats) down from 53.7 and 344 seats in 2018. The center-right opposition party IYIP got 9.7% (winning 43 seats) while the right-wing Victory Party (Zafer Partisi, ZP) obtained only 2.2% and failed to win seats in the TBMM. The predominantly Kurdish YSP obtained 8.8% of valid votes, securing 61 seats, down from 67 seats in 2018. The TİP joined the YSP in the Labor and Freedom Alliance but ran separate lists in several provinces. The TİP eventually obtained 1.8% of the votes and won four seats in the TBMM.

The YSP’s electoral support base is mostly concentrated in the eastern and southeastern provinces and is weaker in other regions. In the large coastal centers of Adana, Mersin, Antalya, İzmir, and İstanbul, the Labor and Freedom Alliance formed by the YSP, the TİP, and several smaller left-wing parties obtained 9-12% of the vote but remained at about half this level in metropolitan Ankara, Kocaeli, and Bursa.

Figure a · Geography of Turnout in the May 14, 2023 Election

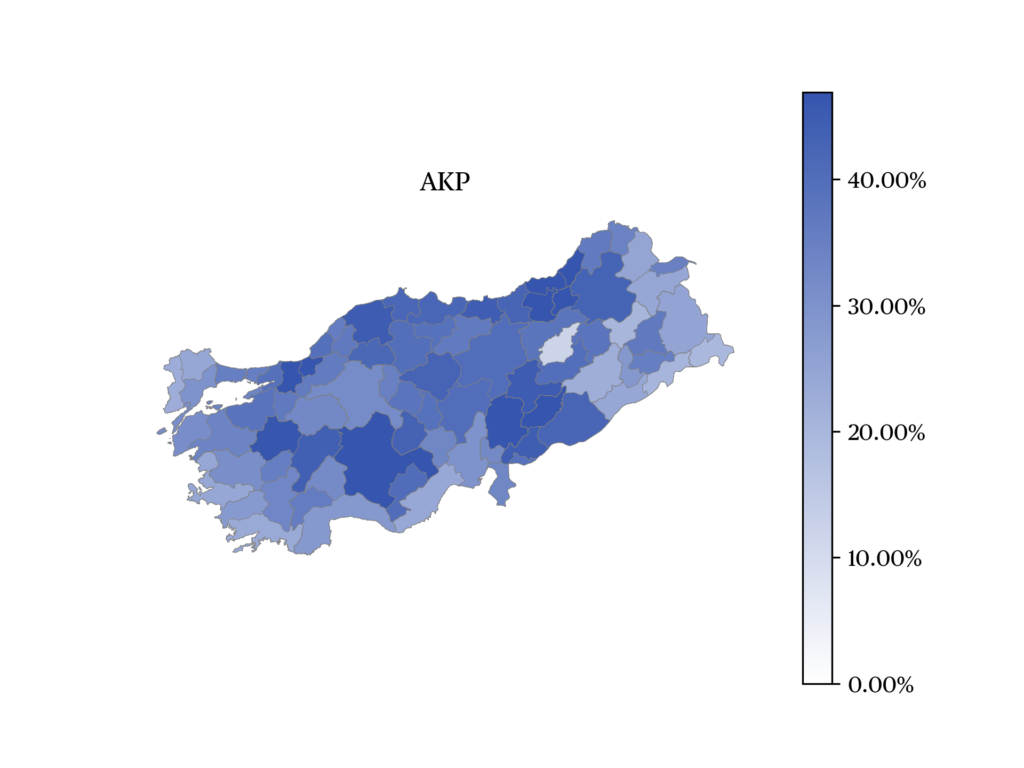

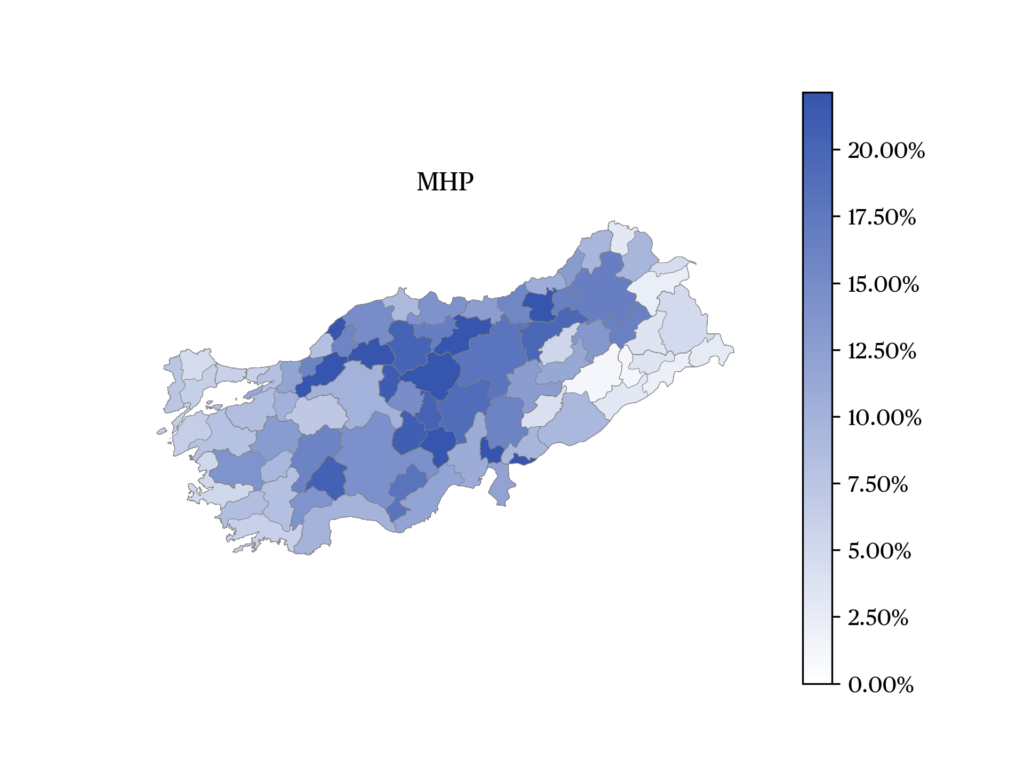

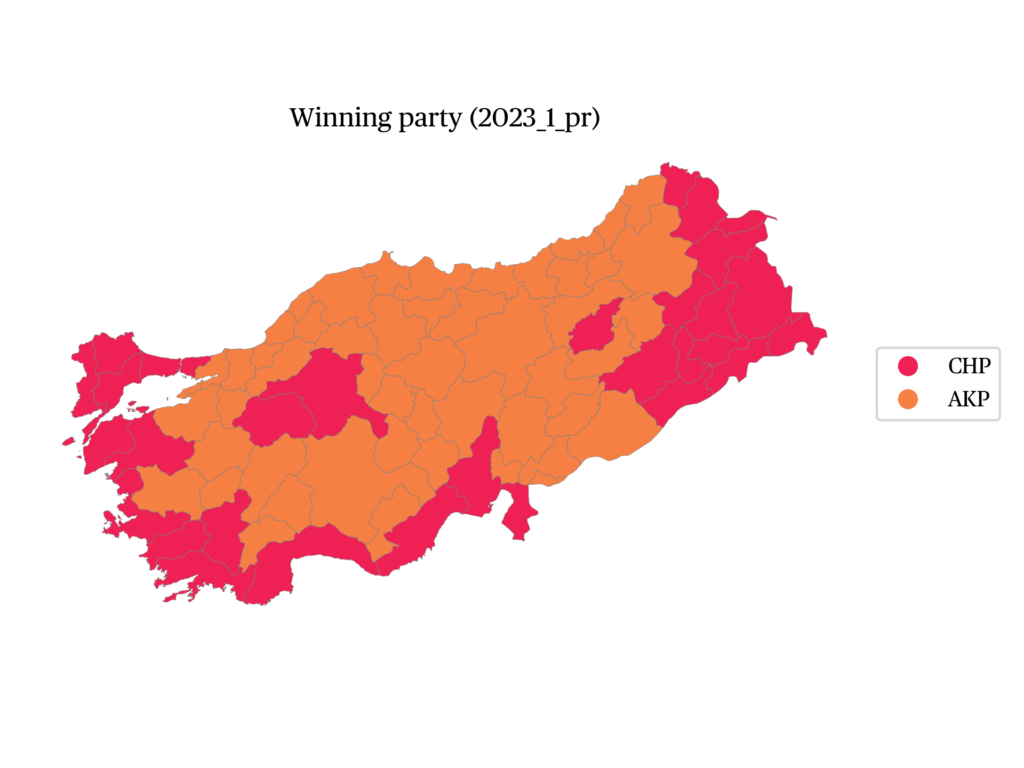

Several patterns are discernible from the geography of party support across Turkish provinces. One is that AKP support is relatively weak in the Eastern and Western coastal regions. Except Adana, Hatay, and Kilis, all other provinces hit by the earthquake lie in areas with the highest level of support for the AKP, as shown in Figure b. It is worth noting that the nationalist partner of the People’s Alliance, the MHP, enjoyed significant support in Kilis, Osmaniye, and Kahramanmaraş, all located in the earthquake region. Their areas of highest support and those of the AKP appear complementary. Hence, the earthquake did not appear to have caused a major electoral upset for the incumbent alliance. Although GP’s leader Ahmet Davudoğlu is from the central Anatolian Konya province, AKP support in this and surrounding provinces remains high. Similarly, the Black Sea coast remains an electoral stronghold for the AKP despite efforts by the opposition’s campaign to target this region. Support for the AKP and MHP appears to have suffered in Ankara but not necessarily in Istanbul, where the People’s Alliance parties secured 46% of the vote, about 10 percentage points above that of the Nation Alliance.

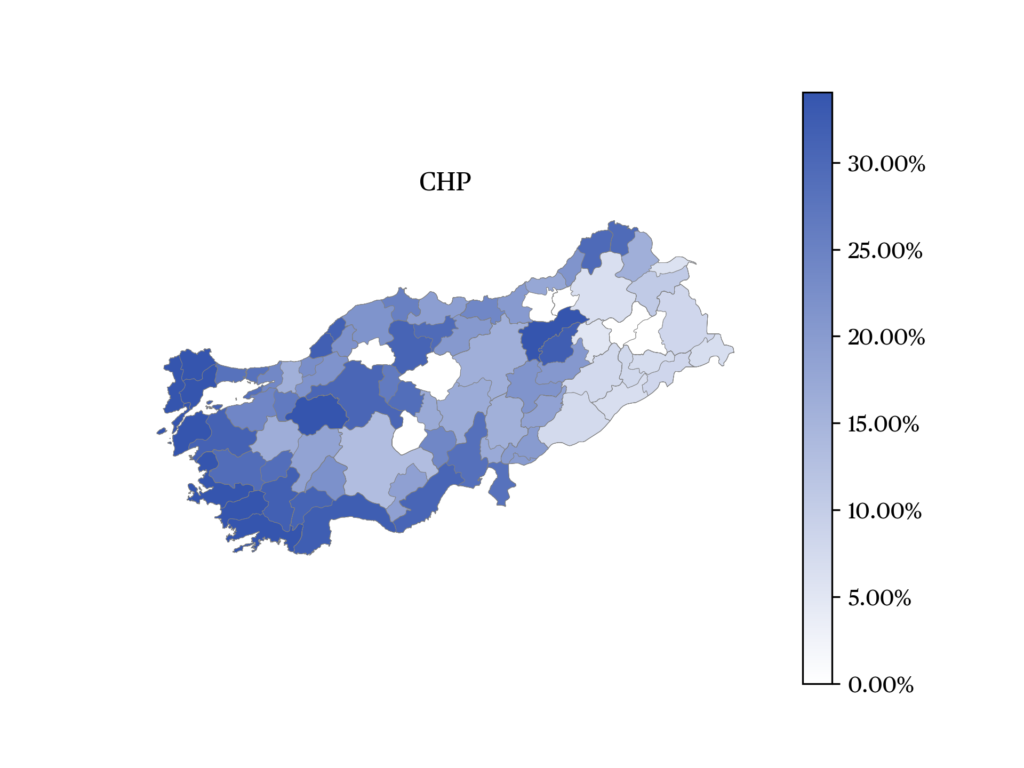

The main opposition party, the CHP, remained very weak in the east and southeast, as well as in the Black Sea and central Anatolian provinces. Within Central Anatolia, the provinces of Ankara, Eskişehir, Çorum, and Amasya stand out with approximately 30% of support for CHP. However, in both Çorum and Amasya, the People’s Alliance was still dominant. Conservative nationalist and pro-Islamist electoral forces in these regions of Anatolia are a well-known phenomenon. The splinter parties from the AKP and MHP, the IYIP, DEVA, and GP, and the traditional pro-Islamist SP, were expected to garner support from the disillusioned ranks of the AKP and MHP. However, their efforts appeared to have been ineffective. The disillusioned AKP voters appear to have switched to either the MHP or the YRP and remained within the People’s Alliance.

The Second Round of the Presidential Election

On the night of May 14, when it appeared that the presidential election will go to the second round, President Erdoğan adopted an optimistic attitude, declaring that he expected a broader victory two weeks later. For several hours, the opposition appeared paralyzed and lost the opportunity to keep its support base mobilized for the second round.

Sinan Oğan obtained more than 2.8 million votes while Muharrem İnce, despite having already withdrawn from the race before the election, received 235,783 votes. Erdoğan needed to keep his support base fully mobilized for the second round and convince only about three hundred thousand additional voters. With the demoralized opposition ranks facing an energetic and optimistic incumbent, the opposition experienced a difficult two-weak campaign.

Negotiations with Sinan Oğan resulted in his eventual support for Erdoğan. As a result, his Ancestral Alliance collapsed after the Victory Party and the Justice Party, both members of the Alliance, supported opposition candidate Kılıçdaroğlu. Kılıçdaroğlu’s campaign adopted an increasingly negative discourse, promising to return Syrian refugees back to their home country and trying to appeal to right-wing Victory Party voters. However, this nationalist rhetoric alienated the Kurdish electorate.

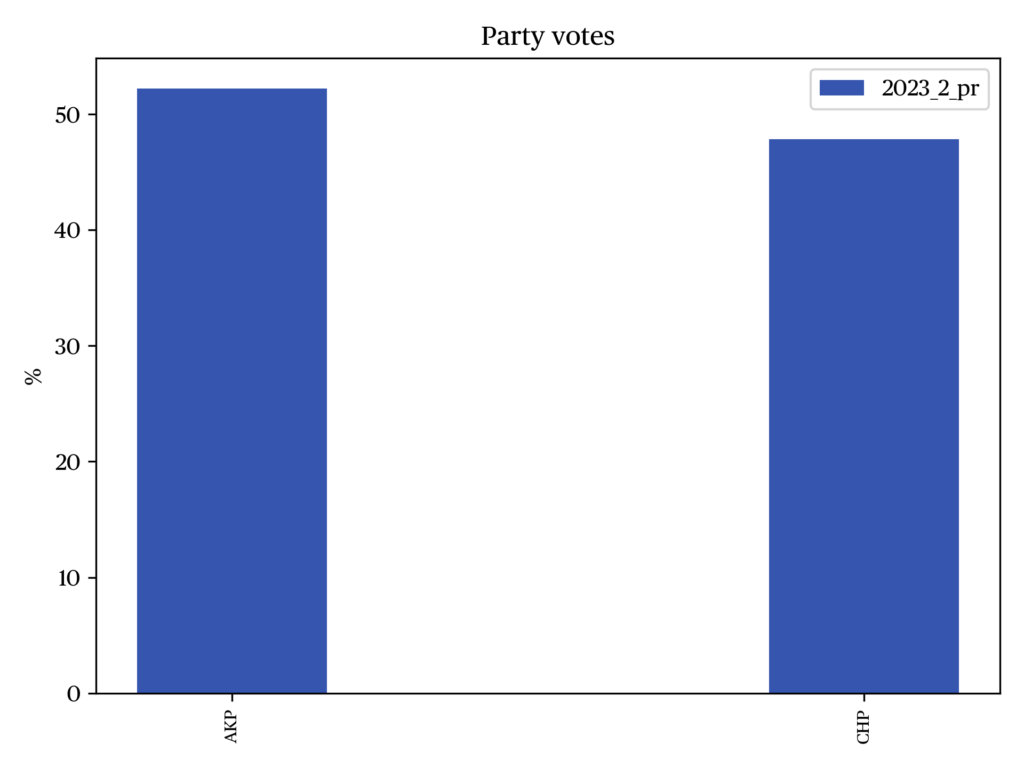

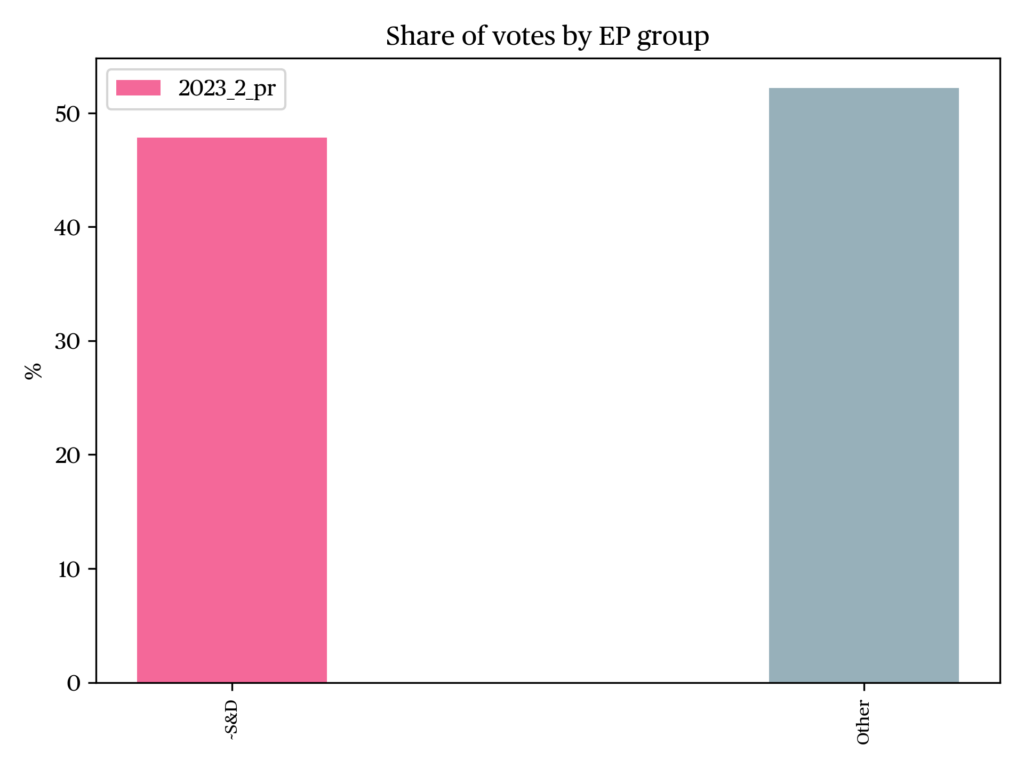

The turnout rate in the second round was approximately three percentage points lower (84.2 %) than in the first round. Once again, the turnout in eastern and southeastern Anatolia was even lower, clearly harming the opposition candidate’s chances. Support for Erdoğan increased by 700,734 voters, while Kılıçdaroğlu obtained an additional 909,546 votes. Erdoğan’s total number of votes was 2,329.865 votes more than Kılıçdaroğlu’s. In other words, only a fraction of Sinan Oğan’s first-round voters appear to have voted for Erdoğan. Even if every single Erdoğan voter in the first round voted for him in the second round and every additional vote obtained by Erdoğan in the second round came from Oğan’s electorate, still less than a fourth (700,734/2,831,239=24.75%) of Oğan voters in the first round must have voted for Erdoğan in the second round. Nonetheless, Erdoğan did manage to mobilize his coalition’s supporters firmly behind his candidacy and attracted a sufficient share of new supporters – primarily among Oğan’s voters – to win the election.

Considering the first-round results, Kılıçdaroğlu needed more than 2.8 million votes to win a majority. This means that if the turnout had remained constant and all Erdoğan and Kılıçdaroğlu voters had voted exactly the same way in the second round, all of Oğan’s supporters should have voted for Kılıçdaroğlu in order for him to win the race. However, in reality the turnout dropped, and it appears that more Kılıçdaroğlu voters did not go to the polls in the second round than did Erdoğan voters. Even though Kılıçdaroğlu increased his voter base by slightly more than 900 thousand, he remained nearly 1.3 million short of winning. If the disillusioned Kılıçdaroğlu voters who did not participate in the second round had turned to support him, the result would have been significantly narrower, and he could even have won. His last-minute appeal to the nationalists of the Victory Party might, in fact, have worked against him, pushing both the Kurdish voters and his core CHP supporters to stay home and not vote in the second round.

Winners and Losers?

Erdoğan perhaps survived the toughest electoral challenge of his career. However, his win came only by moving closer to the nationalist and pro-Islamist fringes of the MHP, the YRP, and HÜDAPAR. This limits his ability to appeal to larger centrist constituencies by delivering social and economic policies. In a sense, this win locks his support within the limits of a marginal pro-Islamist and nationalist agenda.

The next big challenge for Erdoğan and the AKP will be the March 2024 local elections. Immediately after the second round of the presidential election, Erdoğan reshaped his cabinet and reduced the influence of the MHP therein, allowing for a rationalization of his economic policy and reconfiguring the domestic security forces under the authority of the Minister of the Interior. This reshuffle in Erdoğan’s cabinet can be read as an attempt to free himself from nationalist and conservative circles and rationalize his policy agenda before the local elections. The expectation is that the economic recovery will be fast enough to tilt the balance in the local administrations of large metropolitan cities in favor of AKP candidates, especially in Istanbul, Ankara, Adana, and other major urban centers.

Kılıçdaroğlu is the biggest loser of these elections. He lost control of the CHP and was sidelined by a younger generation of political leaders. The IYIP also suffers from party resignations. Similarly, SP, GP, and DEVA clearly proved to be ineffective in appealing to the People’s Alliance electorate. As a result, they lost most of their electoral credibility. In summary, the opposition will face yet another challenge in local elections, where they are expected to hold their ground in at least the major metropolitan races. The Nation Alliance aims to win several of these races to ensure continued electoral credibility. To counter the opposition’s strategy, the People’s Alliance is likely to argue that a single political majority governing at both the central and local level can maximize policy effectiveness in municipalities. It remains to be seen whether this argument will convince voters to shift their support away from the opposition and once again unite under the governing alliance.

The data

Grand National Assembly

Presidential — 1st round

Presidential — 2nd round

References

Aslan Akman, C., & Akçalı, P. (2017). Changing the system through instrumentalizing weak political institutions: the quest for a presidential system in Turkey in historical and comparative perspective. Turkish Studies, 18(4): 577-600.

Aytaç, S. E., Çarkoğlu, A., & Yıldırım, K. (2020). Taking sides: Determinants of support for a presidential system in Turkey. In The AKP Since Gezi Park (pp. 175-194). Routledge.

Cilliler, Y. (2022). Revisiting the authoritarian pattern in Turkey: transition to presidential system. Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 22(2): 263-279.

Notes

citer l'article

Ali Çarkoğlu, Presidential and parliamentary election in Türkiye, May 2023, Jun 2024,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue