Presidential Election in Portugal, 24 January 2021

Eduardo Paz Ferreira

President of the European Institute of the University of LisbonIssue

Issue #1Auteurs

Eduardo Paz Ferreira

21x29,7cm - 102 pages Issue #1, September 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe: December 2020 — May 2021

The presidential election in Portugal happened at a time where each electoral event is under particular scrutiny, in search of signals portending the political future, the resilience of the democratic institutions, the viability of the different partisan alternatives and the gap between voters and the democratic system, as depicted by the abstention rate.

In a context of intense, wide-ranging political troubles afflicting the whole of Europe, the pandemic is yet another factor of social breakdown, a threat that will hardly foster cohesion or reduce the conflicts within societies.

The re-election of Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa in the first round of the presidential election was largely expected and confirmed the tradition by which all the presidents of the Republic democratically elected since 25 April [1976, Carnation Revolution] and the Constitution of 1976, served the two successive terms permitted by the Constitution.

Institutional role of the President of the Portuguese Republic

In the Portuguese semi-presidential system, the president is endowed with powers far from decisive, because he is not at the same time Prime Minister, and the government does not depend on the presidential confidence. However, the president retains broad competences, among which are:

a) To convene an extraordinary session of the Assembly of the Republic;

b) To directly communicate with the Assembly of the Republic and with the legislative assemblies of the autonomous regions;

c) To dissolve the Assembly of the Republic, in compliance with the provisions of Article 172 of the Constitution, after having heard the represented parties and the Council of State;

d) To appoint the Prime Minister, in accordance with Article 187, section 1;

e) To dismiss the Government, in accordance with Article 195, section 2, and to dismiss the Prime Minister, in accordance with Article 186, section 4;

f) To appoint and dismiss the members of the government, proposed by the Prime Minister.

Another crucial aspect of his powers concerns the right to approach the Constitutional Court regarding the constitutionality of the texts transmitted to him by the Assembly of the Republic and by the Government.

Furthermore, his presence in the media and his communication through messages addressed to the Assembly or directly to the voters is another asset of the President of the Republic, as well as an important factor for his image among the Portuguese citizens.

If the abstention rates in the presidential election are generally higher than in the legislative elections, they remain at levels suggesting that the Portuguese are comfortable with the presidential institution.

A quick historic analysis reveals that, generally, when presidents and governments did not belong to the same party, the level of cohabitation remained cordial, despite some inevitable problems.

The powers of the President remain unchanged since the constitutional revision of 1982, which suppressed the possibility for the President to dismiss the government without invoking any ground, which thus ended a situation close to presidentialism and created greater flexibility for the government.

Portuguese presidential elections since 1975

In forty-five years of democracy, Portugal has known five presidents with quite diverse personalities who maintained different relations with the governments. During this period, two phases can be identified: initially, the presidential election was mainly an issue for the military, more or less connected to the political parties and standing for different understandings of democracy — elections of 1976 and 1980 — whereas at later stages, with a few exceptions, the candidates were civilians, with links to the parties or running as independents.

Although the office of President is particularly fit for independent candidacies, the elected candidates are as a rule either presented or supported by a party, without any significant impact on their legitimacy.

Usually, once elected, and sometimes as soon as the election campaign, the candidates insist on presenting themselves as presidents of all the Portuguese, looking to enlarge their electoral base.

The first democratically elected president was General Ramalho Eanes, a key figure of 25 April and of the endorsement of democracy, elected on 25 November 1975.

With the support of most right-wing parties, his first election was easy and the abstention rate low (24.6%), Ramalho Eanes got 61.5% of the vote. Still, a far-left candidate, Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, the strategist of 25 April, got 15.5%. A third member of the military, without partisan support, Admiral Pinheiro de Azevedo, received 14.5%. The only civilian running, Octávio Pat, backed by the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP, GUE/NGL), got 7.5% of the vote.

This peaceful election did not raise any particular difficulties, highlighting in particular the rise in power of the revolutionary left linked to certain military sectors. The latter had seen their power diminish, however, after the military coup of 25 November 1975, which consolidated the moderate sectors in the armed forces. They had been re-elected in the first round with 53%, followed by the PS and BE candidate, Manuel Alegre (19.6%) and the independent candidate Fernando Nobre (14.1%). The PCP’s Francisco Lopes remained at 7.7%.

These last two elections thus show a certain difficulty for the Socialist Party to manage presidential elections.

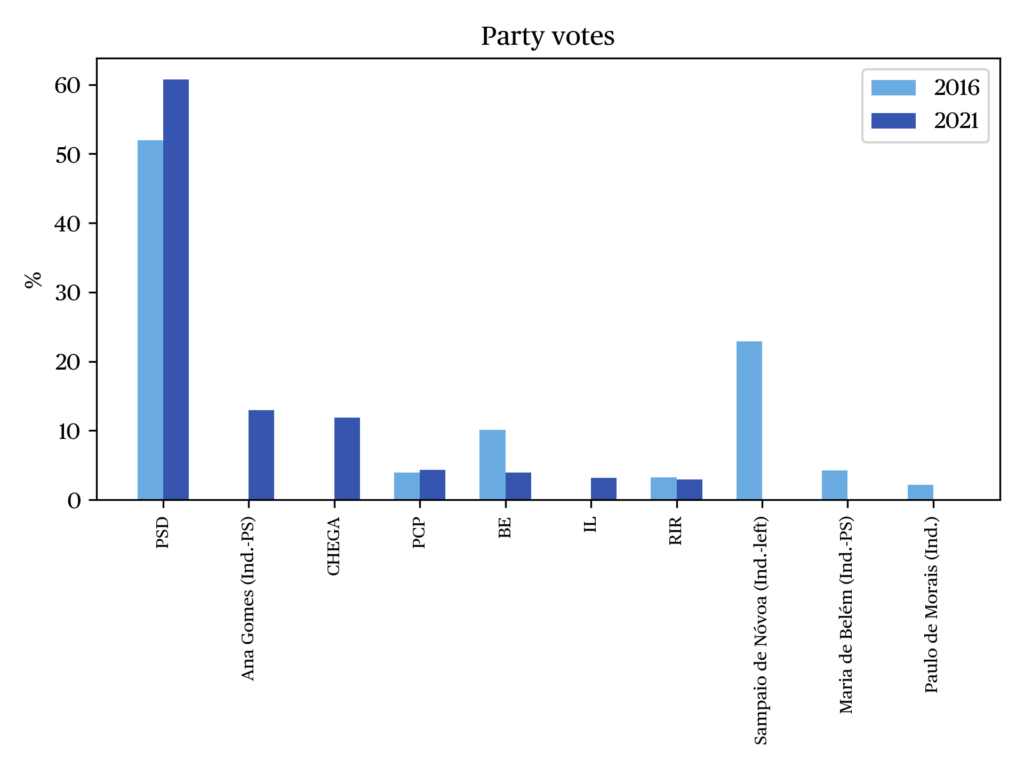

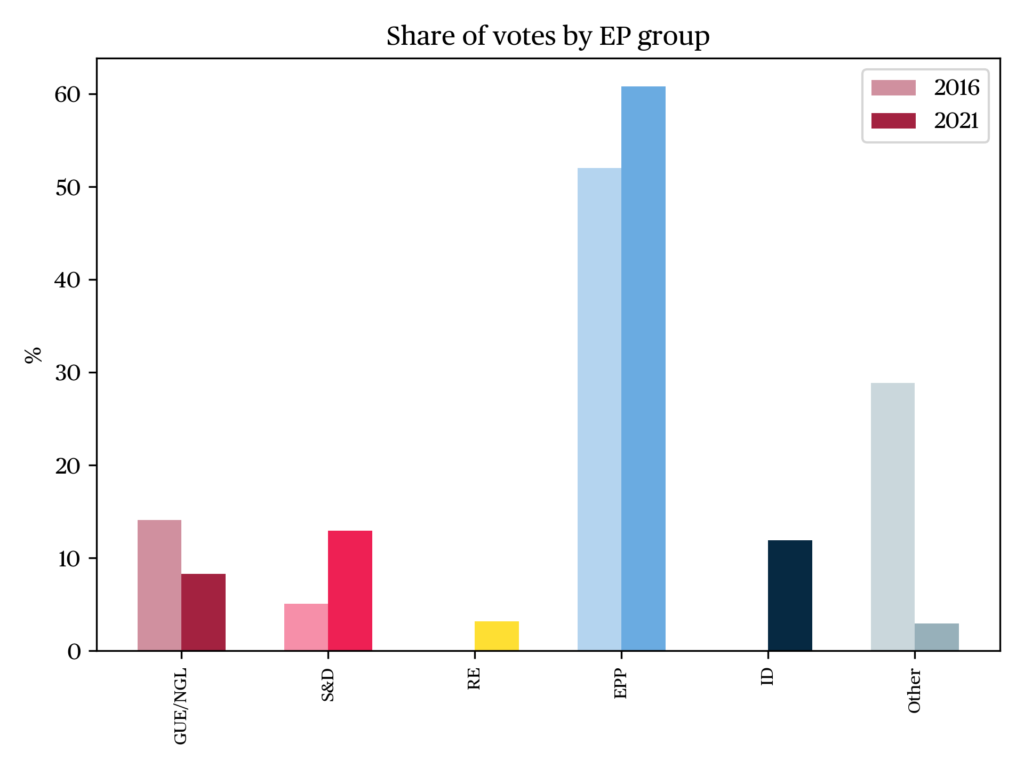

In 2016, Marcelo Rebelo Sousa, who as leader of the PSD had previously not achieved favourable results, won the election with 52% of the vote, supported by the right-wing parties and garnering a significant share of the socialist and independent vote. His career as a political commentator on television and extremely favourable polls played in his favour. His main opponent, Sampaio da Nóvoa, a former rector of Lisbon University who was counting on the votes of the PS, ended up with 22.8% of the vote, while the party also did not support another of its leaders, Maria do Belém Roseira (4.24%).

The big surprise was the result of BE candidate Marisa Matias (10.12%) and the low score of the PCP candidate.

Results of the January 2021 election

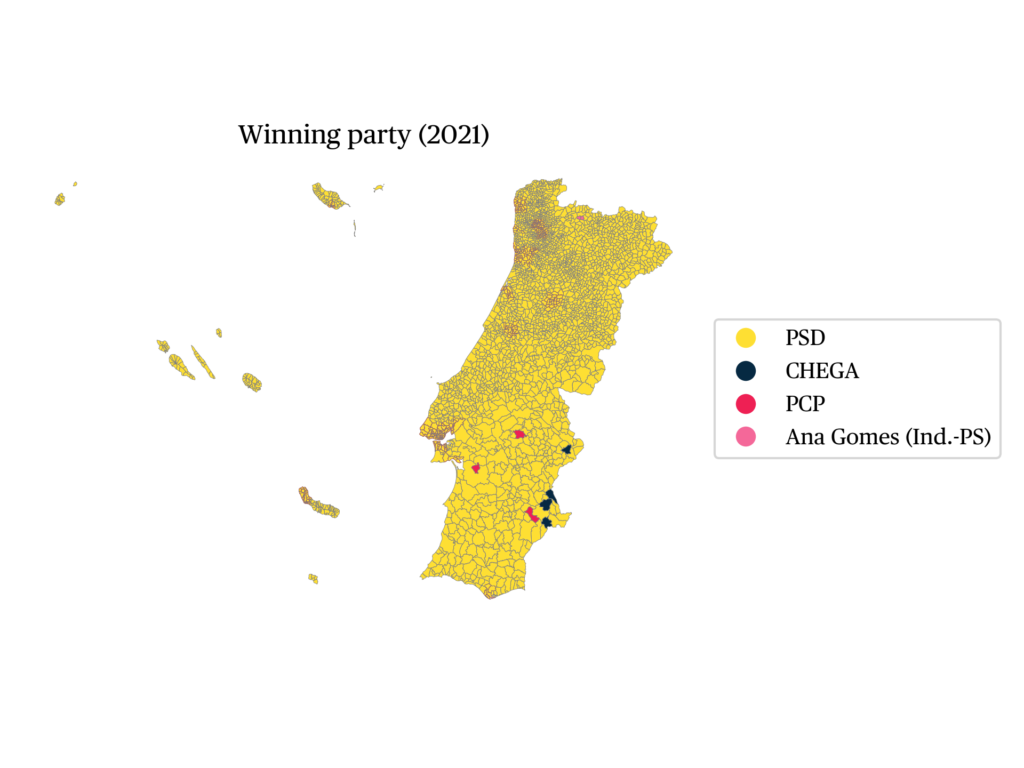

The re-election of Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa in 2021, after a first mandate marked by great popularity, is without surprise. It follows the logic of previous elections, exempting the winning candidate, elected with more than 60% of the vote, from a second round. The abstention rate has also risen to 54%, a figure that must, in any case, be read in the light of the peak of the pandemic that coincided with these elections.

The result consolidated Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa’s position and suggests that he will continue to play a central role in Portuguese politics. The implicit support of the PS is expected to lead to the continuation of intense cohabitation and cooperation between the President of the Republic and the Prime Minister, as several PS figures have given their express support to Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa. The Prime Minister and Secretary General of the PS, António Costa, did so implicitly.

Once again, the PS did not present a candidate, although one of its leaders, Ana Gomes, usually placed on the left of the party, came second (12.97%), supported by the small People-Animals-Nature party (PAN, Greens/EFA). The candidate’s result, while lower than Sampaio da Nóvoa’s in the previous elections, could strengthen her role in the party, however without leading to any radical changes.

A novelty, but of more limited significance, was the score of the Liberal Initiative (IL, ALDE) candidate, who had support in the media; he obtained 3.22% of the vote. However, it is unlikely that liberalism, which is not well established in Portugal, will have a great electoral future.

The results of the left-wing candidates were quite low, with João Ferreira of the PCP obtaining 4.32% of the votes and Marisa Matias 3.95%, apparently victims of the strategic vote to Ana Gomes to prevent André Ventura (CHEGA, ID) from coming second. The next elections will show whether these parties are able to regain their previous electoral weight.

André Ventura, candidate of the recently founded far-right Chega party, came third with 11.9% of the vote; his score is probably the most important novelty of these elections.

The far right, which had only one member in the Parliamentary Assembly, will be able to institutionalise itself and become part of the establishment it claims to oppose. The normalisation of hate speech and xenophobic and racist appeals has received enormous media tolerance, and the party is now likely to follow a similar trajectory to other comparable European parties.

Consequences of the election

The beginning of Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa’s second term in office was different from the first, mainly due to the Covid-19 pandemic and its economic and social effects, which at times made it somewhat difficult for the President and the Government to reach an agreement and to define areas of competence.

Despite this, Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa seems determined to avoid any political crisis and will tend to maintain the current governing conditions. This has allowed for an excellent Portuguese Presidency of the Council of the European Union in the first half of 2021, despite all the difficulties, and has put the country on track to receive support from European aid mechanisms, once the national programme has been approved.

During the second term we saw a gradual hardening of the political debate, with political discourse giving way to partisan bickering and attempts to replace debate with the exposure of real or fake scandals.

Although the media are all opposed to the Government, new digital and even print newspapers continue to appear along the same political lines and social networks have reached levels of indignity never imagined and close to those that have emanated from the Trump presidency.

Despite this, the Socialist Party and, in general, all the left-wing forces are still largely favoured in the polls with little variation.

With the hypothesis of a central bloc moving further and further away, the most likely option is for the socialists to continue to govern with the help of ad hoc support, especially from the PCP, which does not seem to be willing to give the right any opportunity to return to power through elections.

As mentioned earlier, the President of the Republic also prefers this solution to any other that could create a political deadlock, since there is no indication that a right-wing majority will be formed.

The parties of the traditional right, on the other hand, have experienced a significant erosion in favour of the far right, with whom they maintain an ambiguous relationship: sometimes coming closer, as is the case with the regional government of the Azores, a political region, where the regional government is supported in parliament by Chega; at other times distancing themselves from it by refusing coalitions.

Within this framework, the smallest traditional party, the CDS, seems to be the most threatened, with figures showing a very significant decline.

In a difficult situation, the centre-right parties radicalise their discourse and bring it closer to far-right positions, thus losing votes from the centre, without preventing transfers to the right.

Chega is, of all the far-right parties, the one that has made the most progress, based on a racist and xenophobic discourse that takes advantage of popular discontent.

Next October, the local elections will be an important barometer for the future, which will allow us to see if the political system will change in a very significant way, which does not seem likely, or if it will keep more or less the same pattern, dealing with the newcomer, Chega.

From the point of view of the presidential mandate, I do not think there will be any great changes, but only a strengthening to promote greater political rapprochement.

The Data

citer l'article

Eduardo Paz Ferreira, Presidential Election in Portugal, 24 January 2021, Sep 2021, 25-28.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue