Provincial and Senate elections in the Netherlands

Simon Otjes

Assistant Professor, Leiden UniversityIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Simon Otjes

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

Introduction

The 2023 Dutch provincial elections, which indirectly elected the Senate a few months later, saw a major change in the political landscape when a party with only one seat in the lower house suddently became the biggest party in the upper house. A small agrarian populist party, the Farmer-Citizen-Movement (BoerBurgerBeweging, BBB) was catapulted to first place due to dissatisfaction with the agricultural policy of the government, the neglect of rural areas and broader discontent with the cabinet. The party won at the cost of radical-right and centre-right parties.

The elections primarily concerned the Dutch provinces, whose responsibilities are primarily in the physical domain. These are mainly responsible for zoning, infrastructure, the environment and nature. A few months after their election, the Provincial Councils in turn elect the Senate, which has unconditional veto power over all legislation. A government without a majority in the Senate would need support from opposition parties to pass legislation.

This article first sketches the context of the 2023 provincial elections, in particular the government formation after the 2021 national elections and the on-going nitrogen crisis. It then examines the performance of the different parties. A special section discusses the intricacies of the Dutch Senate election that followed the provincial elections. The final section discusses the relevance of the elections from a broader perspective.

The social and political context

The outcome of the 2023 Provincial elections should be understood in the context of the formation of an unpopular government after the 2021 national election and the ongoing nitrogen crisis.

Government formation of 2021-2022

The 2021 election took place after the existing government of Liberals and Christian-democrats, in government between 2017 and 2021, had stepped down over a major scandal surrounding the overzealous prosecution of people who had committed relatively minor infractions with childcare benefits (Otjes 2021b). The government parties – the Liberal Party (Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie, VVD, Renew), the social-liberal Democrats 66 (Democraten 66, D66, Renew), the Christian-democratic Appeal (Christen-Democratisch Appèl, CDA, EPP) and the Christian-social ChristianUnion (ChristenUnie, CU, EPP) – kept their majority in the election, despite the scandal and despite having stepped down.

At first, D66 had vetoed the continuation of the existing government because they had promised ‘new leadership’: they did now want to govern with two Christian-democratic parties and instead wanted the social-democratic Labour Party (Partij van de Arbeid, PvdA, S&D) and the GreenLeft (GroenLinks, GL, G/EFA) to enter government. But these two parties only wanted to govern together, while the CDA and the Liberal Party opposed two left-wing parties joining the government. This created a deadlock: all possible governments were blocked by one of the respective possible partners. As a result, the process of cabinet formation undermined public trust in the sitting PM (Kester 2021). One painful incident happened when prime-minister Mark Rutte suggested that “a position elsewhere” should be found for the critical CDA MP Pieter Omtzigt who had put the childcare benefit scandal on the agenda. This was leaked accidentally. After months of talks, D66 accepted the continuation of the existing government under Rutte. A new cabinet was installed in January 2022, almost a year after the fall of the previous one (Otjes & De Jonge 2023).

The new coalition tasked itself with restoring the public confidence in the government (Coalition agreement 2021). The loss of public confidence resulted, among other causes, from the incident-ridden coalition formation and several scandals (among which the aforementioned childcare benefit scandal, but also a scandal over gas extraction permits in Groningen despite seismic risks, as well as the increasingly salient nitrogen crisis).

The nitrogen crisis

In 2019, just before the Corona crisis, the Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte called the nitrogen crisis the most difficult issue of his tenure as PM (Otjes & Voerman 2020). The Netherlands has to abide by the EU habitat directive, which requires preventing the deterioration of nature protection areas, especially Natura 2000 areas. 1 A major reason for the decline of biodiversity in the Netherlands is nitrogen pollution: intensive animal husbandry produces ammonia and combustion in vehicles and the industrial sector produces NOx. The effect of these emissions on protected areas consists in plants which thrive on nitrogen replacing the preexisting diversity of plants. With intensive animal husbandry and a strong transportation sector in a very densely populated country, nitrogen pollution is a much bigger issue in the Netherlands than elsewhere. The Netherlands is the second largest exporter of food in the world, which can be explained both by the role of the harbor of Rotterdam and Schiphol airport as important transit hubs and by the country’s extremely efficient agricultural sector. As a result, about two-thirds of the domestic nitrogen emissions stem from agriculture. In 2009, the coalition created a policy to deal with nitrogen pollution, which aimed at compensating current construction plans or extensions of farms with future decreases in nitrogen emissions.

In 2019, the Council of State, the highest administrative court, ruled the existing nitrogen compensation system illegal (Raad van State 2019). The ruling meant that those who wanted to construct roads or extend farms had to prove that their plans did not increase net nitrogen emissions: either nitrogen pollution would be prevented 2 or the increased nitrogen pollution would be compensated. As a consequence of the ruling, the government was tasked with limiting net emissions from agriculture, transport and industry in order to keep to the habitat directive. A myriad of solutions was attempted, all to no avail. The government tried to deal with this issue with patchwork laws which were once more struck down by the Council of State. A committee of experts was later appointed to offer a holistic agenda (Adviescollege 2020), and the government tasked a special negotiator with discussing pollution reduction strategies with the agricultural sector. In 2022, however, the minister of agriculture stepped down, being unable to deliver a long-term vision for the sector. Maps with areas where the government proposed to decrease the number of farms were first floated by the minister of Nature and Nitrogen Policy, but were quickly retracted. So far, none of the attempted solutions have succeeded, partly because the agricultural sector is unwilling to accept forced buy-outs of farms near protected areas. In 2019, 2022 and 2023, major protests were organized by farmers’ organizations and big agricultural companies. Some of these protests turned violent – with Ministers being threatened at their homes, tractors brought into cities creating dangerous situations and the police shooting a 16-year old farmers’ son. 3

The net result of all this is that construction projects (of roads and houses) are now postponed until the associated nitrogen pollution can be compensated. The centre-right government is caught between three interests. Firstly, the interest of the agricultural sector. For the Christian-democrats, in particular, the ties to farmers and rural areas are an important part of their identity. Since the 1990s, the Christian-democrats have tried to protect the interest of the agricultural sector from the need to reduce ammonia pollution. Secondly, the interests of the environment. The social-liberal party D66 is particularly committed to protecting nature, even if this means halving the number of livestock in the Netherlands. Thirdly, the construction of new houses. The demand for houses in the Netherlands outpaces the supply, in particular in the populous west of the country. The nitrogen ruling has meant that many housing projects could not be started because the nitrogen pollution could not be compensated. The conservative liberal VVD is strongly committed to constructing new houses (in the words of one of their MPs, his three priorities are “building, building, building”).

The Provincial Election Results

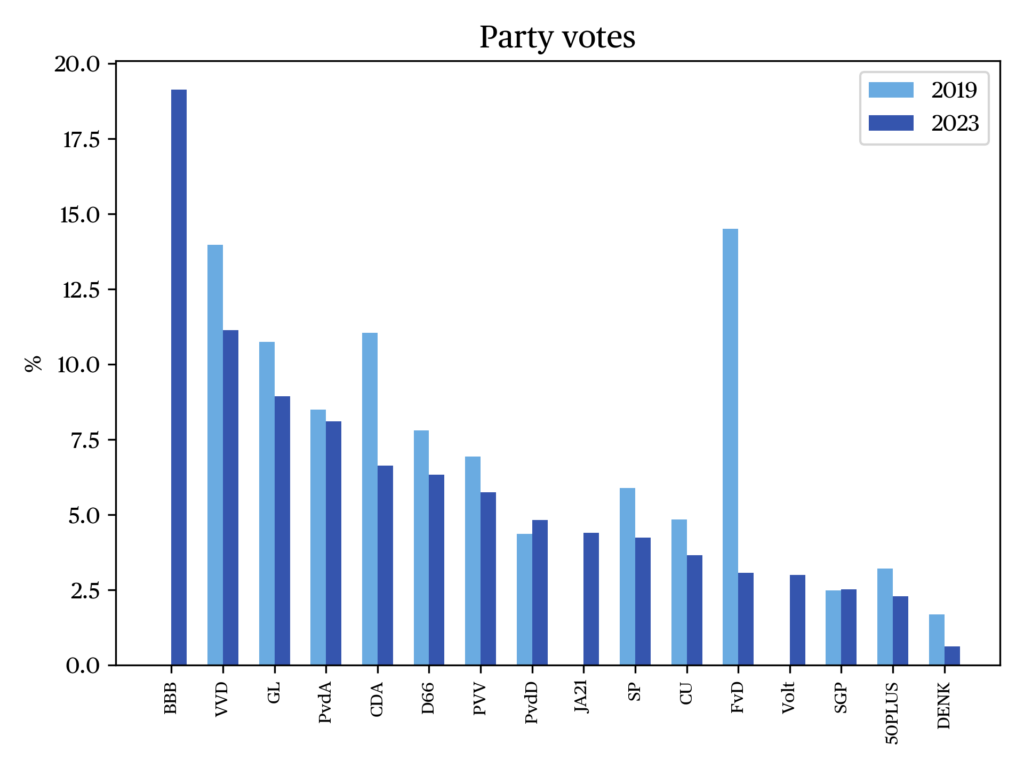

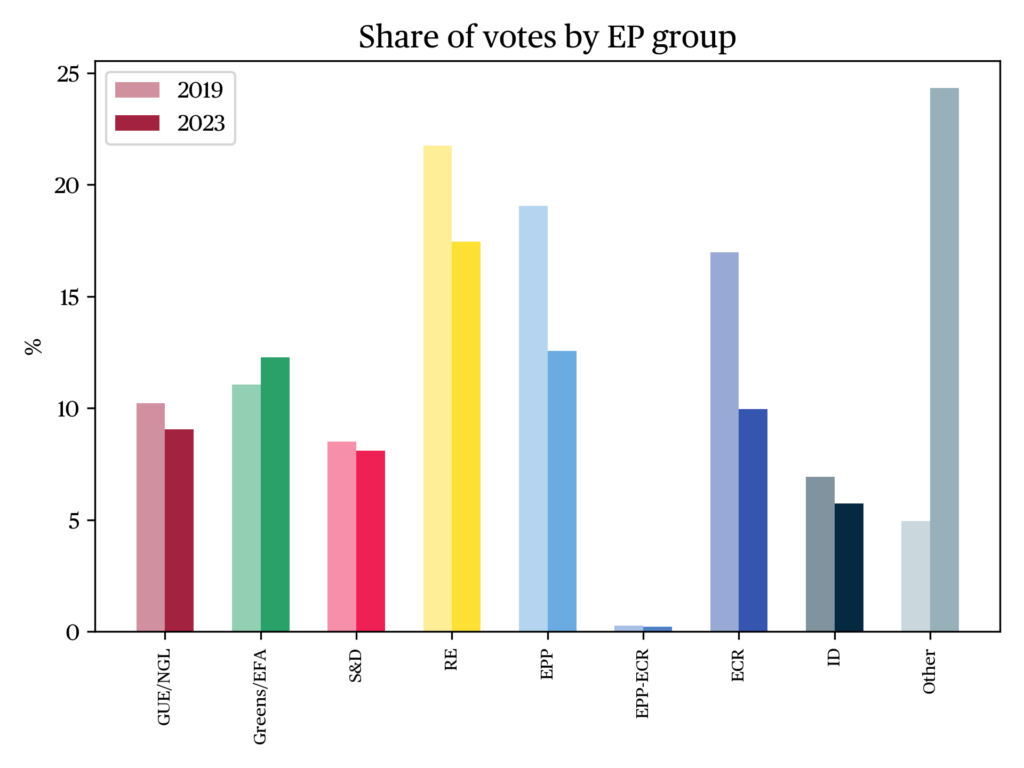

The elections resulted in major change in the composition of the Senate: the BBB, which was not represented in the provincial councils before, became the largest party. Turnout was higher than in the last provincial election (58%, up two percentage points). In order to explain the political landscape in the next sections, we split the parties up into five clusters: the new party BBB, the centre-right government coalition, parties to the left of the coalition, parties to the right of the coalition and three small centrist parties. Polling data come from IPSOS (NOS 2023).

The Big Brand-new Bloc

The big winner on election night was the Farmer-Citizen-Movement. This small populist agrarian party was formed in 2019 and won its first lower house seat in the 2021 national election. The party has outspoken positions on the future of farming in the Netherlands. It opposes the forced buy-outs of farmers. On other issues, the party mixes left-wing positions (e.g., the return of public health insurance funds and legalizing soft drugs) with right-wing positions (e.g., lowering fuel taxes and more restrictive migration policies). The BBB uses populist rhetoric, emphasizing how political elites have grown estranged from voters, especially those from rural areas, and combines this rhetoric with an emphasis on common sense by its leader Caroline van der Plas (Voerman & De Jonge 2023).

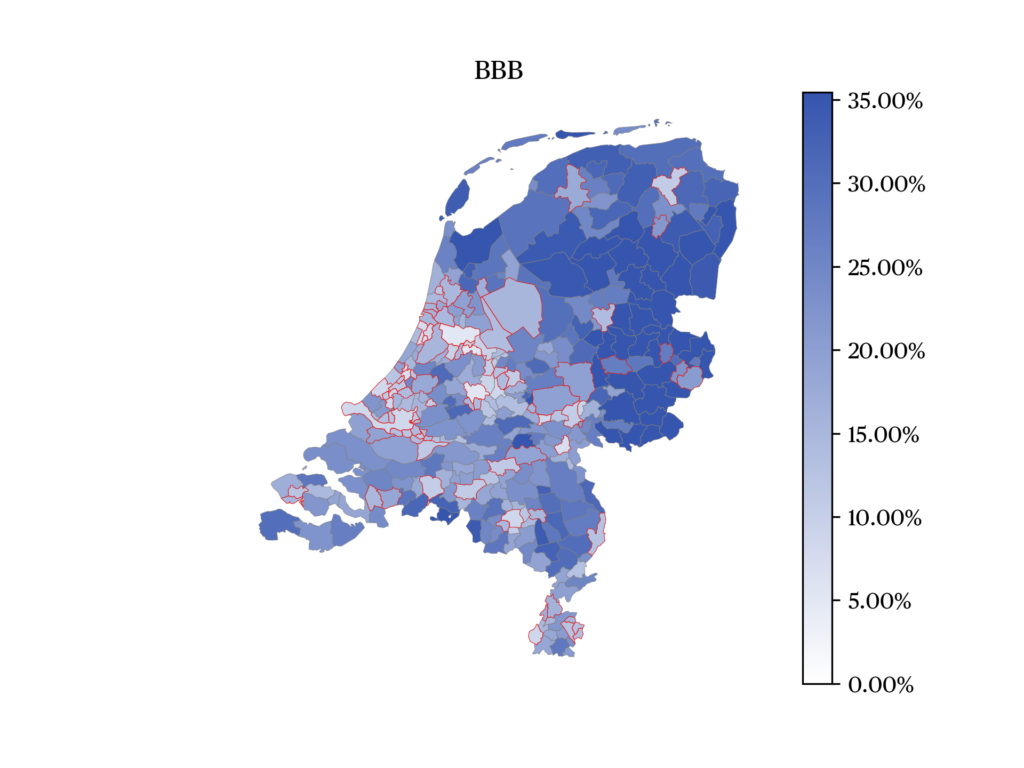

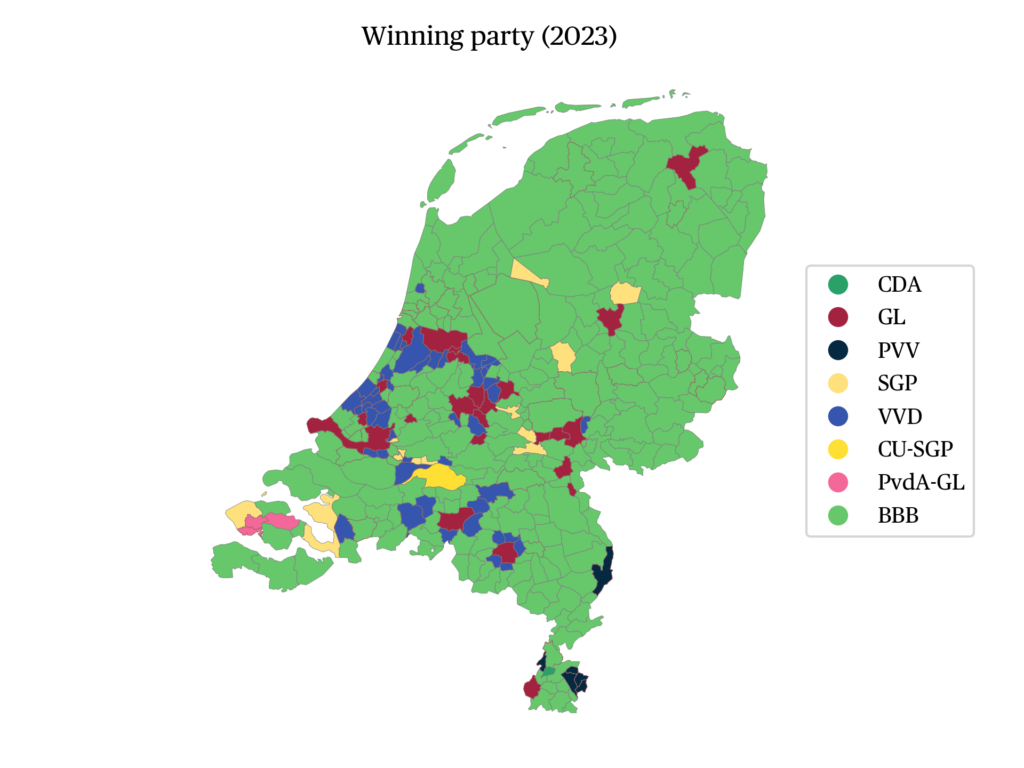

In the 2023 provincial elections, the BBB became the largest party with a fifth of the votes, compared to 1% of the national vote in the 2021 lower house elections. It is the largest party in every province – the first party ever to do so. The party was strongest in rural North-Eastern provinces like Gelderland, Overijssel, Drenthe, Groningen and Frisia, and did much better in rural than urban areas: only 30% of its voters live in urban areas, compared to half of its voters who live in rural areas.

The BBB won the elections mobilizing on three forms of dissatisfaction. Firstly, the party capitalized on voters’ dissatisfaction with the nitrogen policy of the government. The BBB is not just a farmers’ interest party: Dutch farmers are just 0.5% of the population, too few people to become the largest party. Secondly, the party scored well in peripheral areas where there is dissatisfaction with the lack of government attention to rural areas, as most government policy is focused on the populous cities (Lieviesse Adriaanse 2023). Voters in these peripheral areas believe that the government has done too little to support their region economically (De Lange et al. 2023; Huijsmans 2023; De Lange 2018). Finally, the BBB benefitted from a general dissatisfaction with the government’s inability to deal with the major crises it faced (e.g., the child benefit allowance scandal, the Groningen gas extraction scandal and inflation). The BBB won votes of people who voted PVV, VVD and CDA in 2021.

The BBB stands in a longer line of rural populist parties (Vossen 2015): between 1918 and 1937, the Peasants’ League (Plattelandersbond, PB) was represented in parliament. This party likewise wanted to address the disadvantage experienced by rural areas. Later, between 1963 and 1981, the Farmers’ Party (Boerenpartij, PB) also held parliamentary seats. This party started out as a farmers’ interest party opposed to the regulation of the agricultural sector but grew out to be a gathering place for all kinds of political nomads right of the mainstream liberals and Christian-democrats. This party adopted populist rhetoric as well. Interestingly, despite being decades apart, the BBB, BP and PB all did quite well in the same areas in the North-East of the Netherlands. The BBB stands in a longer line of rural populist parties in Europe, in particular in the Nordic countries, such as the historic Finnish League of Rural People (Suomen Maalaisväestön Liitto) but also the current Norwegian Center Party (Senterparti). Compared to traditional agrarian interest parties, these parties use populist rhetoric to mobilize voters by focusing on the cultural difference between the city and rural areas. They make a distinction between the “us”, who live in rural areas and “them”, the urban elites (Arter 2023).

The Coalition Parties

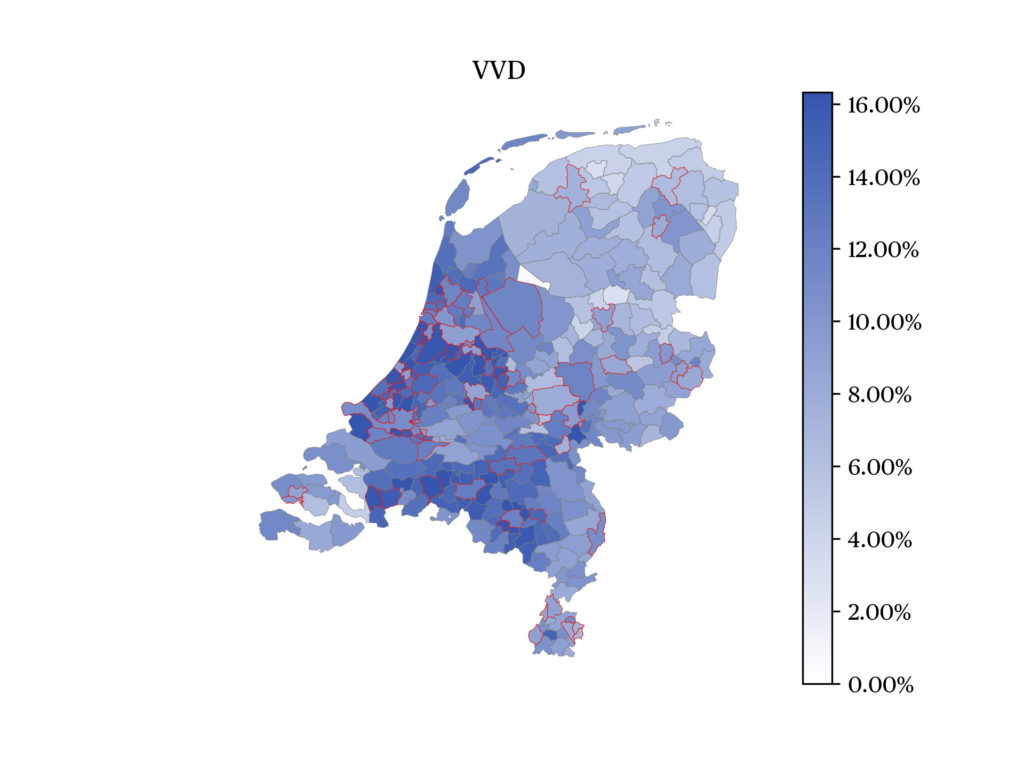

The centre-right coalition of Liberals and Christian-democrats was anticipated to lose seats in this ‘mid-term’ election. The question was only how bad the result would be. The Liberal Party (Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie, VVD, Renew) had hoped to create a horse race between them and the GreenLeft-PvdA combination (see below) by focusing on economic issues and warning that if the latter did well in the elections, they would raise taxes. 4 This strategy proved unsuccessful and instead, the VVD lost a fifth of its voters compared to 2019, ending up in third place. It only did well in suburban and urban areas in the West and South of the country.

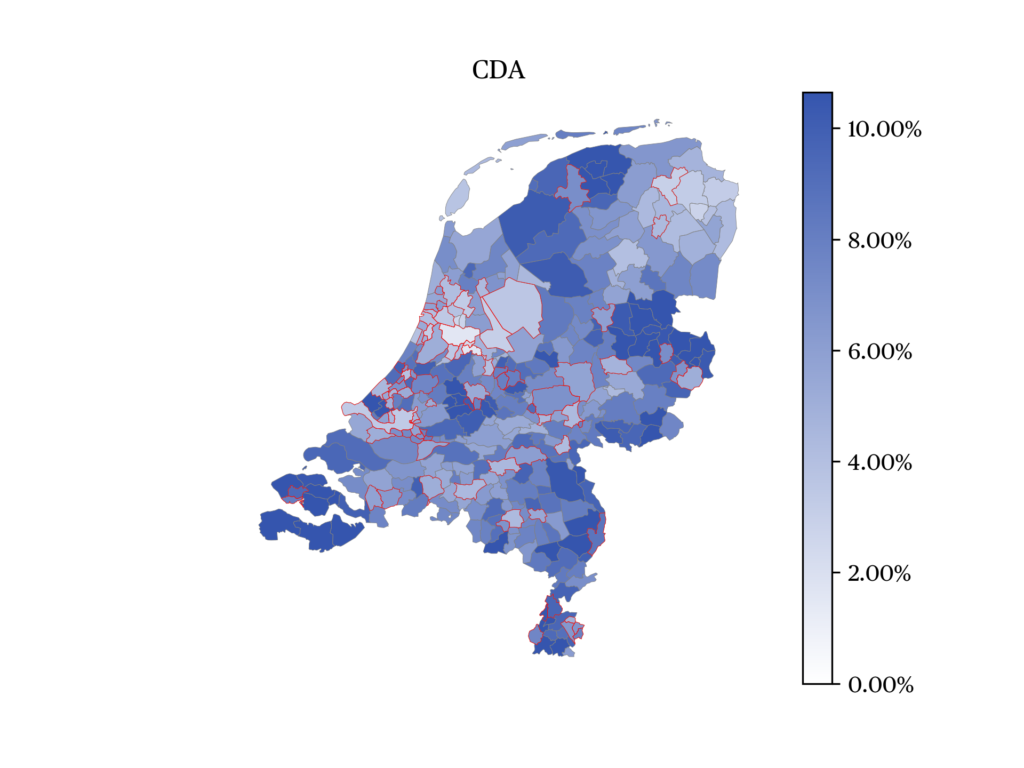

The Christian-Democratic Appeal (Christen-Democratisch Appèl, CDA, EPP) had been polling poorly since the summer of 2021, when the popular MP Pieter Omtzigt left the party. In addition to loosing this popular MP, the party was weakened by the major concessions it had made to D66 and its inability to alter the coalition’s nitrogen policy, despite having repeatedly voiced its disagreement with the plan. In the end, the CDA lost about two fifths of its support compared to 2019. The party lost votes in rural areas in Brabant, Limburg and Overijssel, where the party traditionally did well. 40% of its voters live in rural areas.

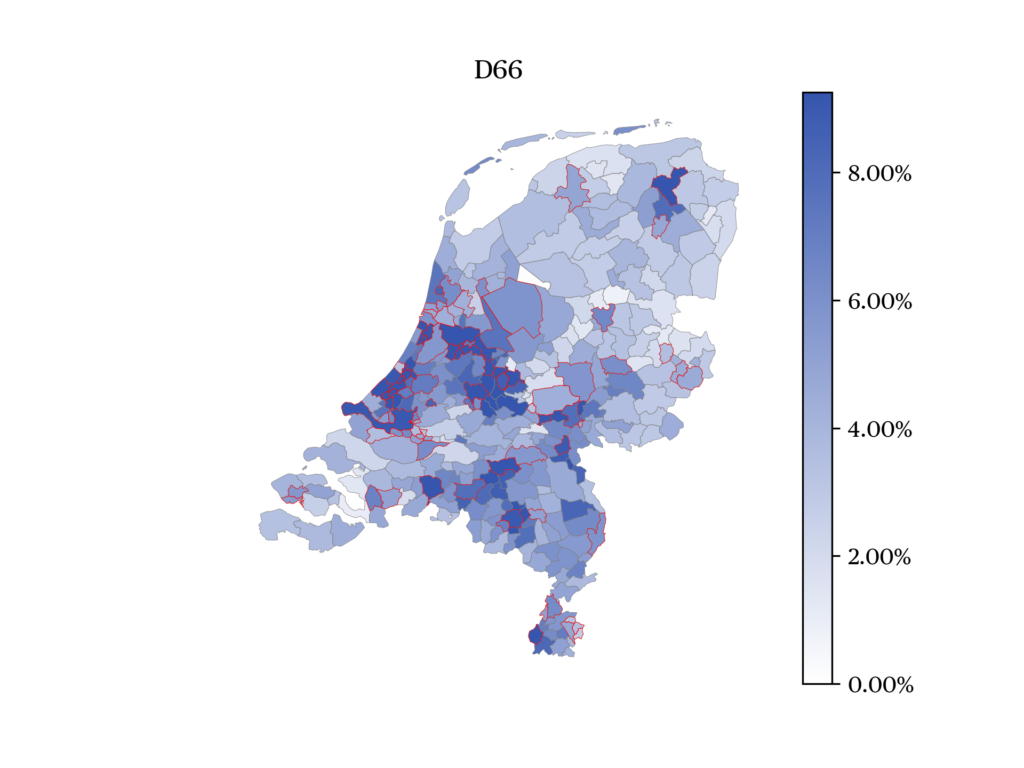

The social-liberal Democrats 66 (Democraten 66, D66, Renew) had also declined in the polls compared to the 2021 election, which it had won under the slogan ‘new leadership’. D66 was forced to accept a continuation of the existing and by then unpopular centre-right government. On many issues, the centre-left positions of D66 did not match those of its coalition parties: on nitrogen/nature policy and on migration, D66 was in continual conflict with CDA and VVD. In 2023, D66 lost a fifth of its votes compared to 2019. The party was strongest in suburban commuter towns in the West of the country. 60% of its support comes from urban areas.

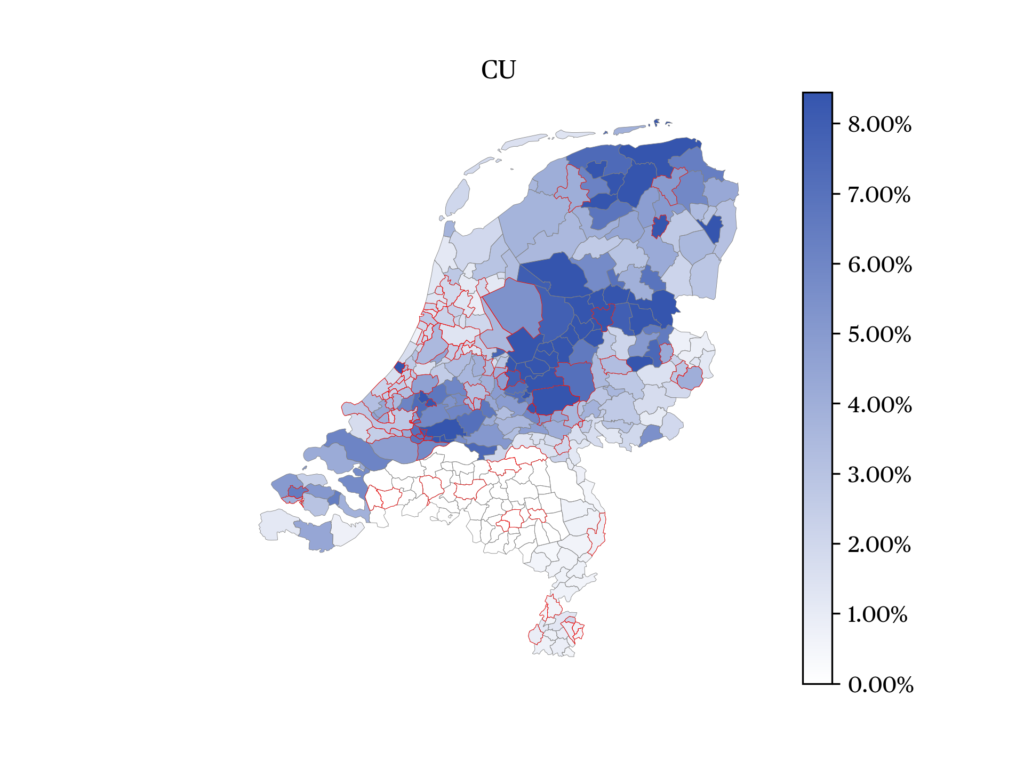

The Christian-social ChristianUnion (ChristenUnie, CU, EPP), although traditionally one of the most electorally stable parties, lost a quarter of its votes compared to 2019. The issue of nitrogen drove a wedge between the relatively pro-environmental party leadership and its traditional base living in the rural protestant ‘bible belt’ that runs from the South-Western province of Zeeland to the North-Eastern province of Groningen.

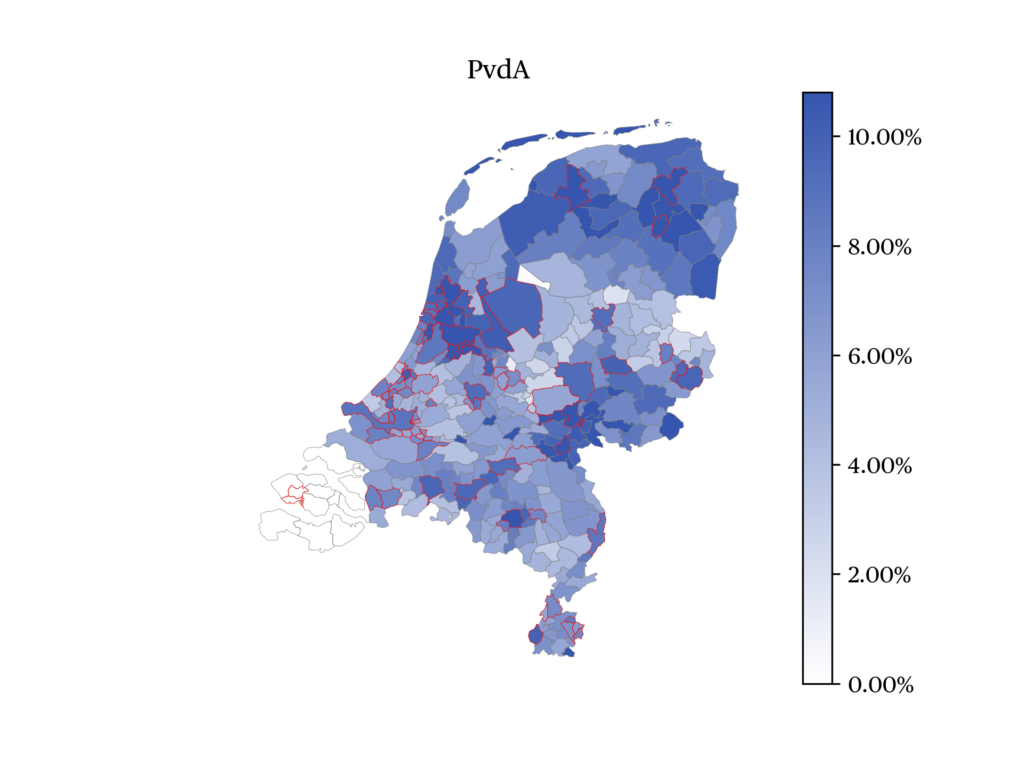

The Left-wing Opposition

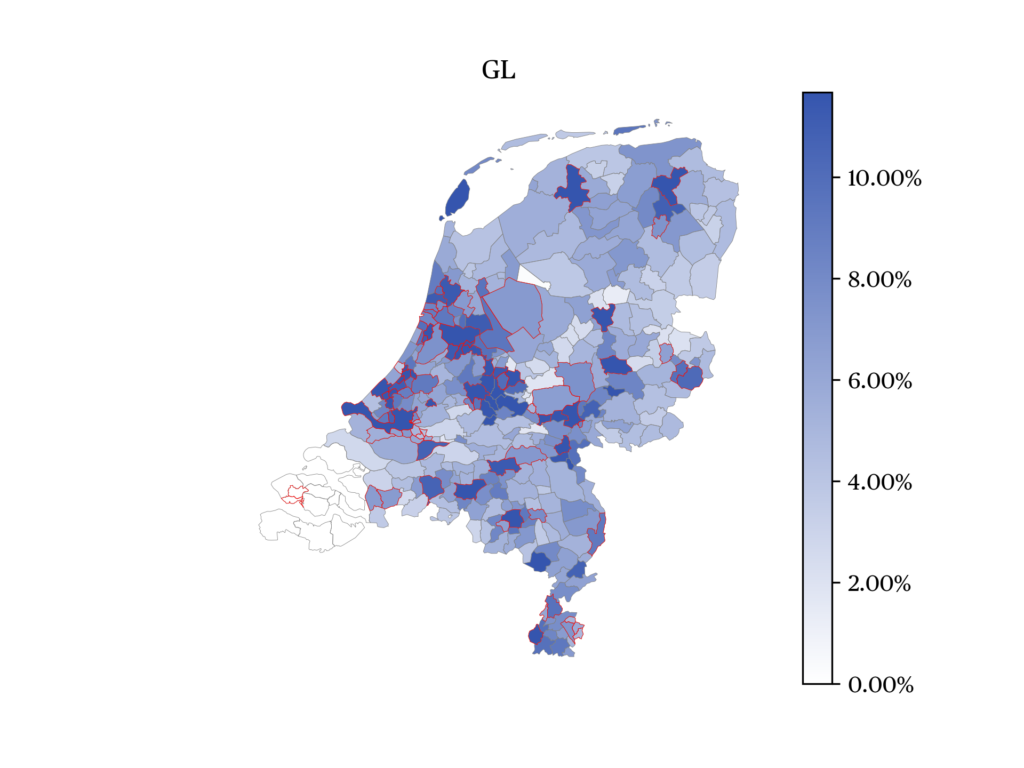

To the left of the government, there are four parties: the GreenLeft, the Labour Party, the Socialist Party (Socialistische Partij, SP, GUE/NGL) and the deep green Party for the Animals (Partij voor de Dieren, PvdD, GUE/NGL). The GreenLeft and the Labour Party cooperated intensively in these elections. In the summer of 2022, they had committed themselves to a common senate group after the elections (Otjes & Voerman 2023). The cooperation was meant to prevent the two parties from being played out against each other by the government searching for a majority in the Senate. In the South-Western province of Zeeland, PvdA and GL ran on a common list. The VVD’s attempt to create a horse race for the mainly symbolic position of becoming the largest party in the Senate was embraced by GL and PvdA: they focused on the idea that, if they became the largest party in the Senate, they would be able to force the government to the left – both on economic issues and on environmental policy. Given that the largest party in the Senate does not have special policy-making power, this claim should be taken with a grain of salt. However, what was crucial for GL/PvdA was that their negotiation power would be greater if the coalition and GL/PvdA would together command a majority in Senate. But despite trying to get into a horse race with the VVD, both parties lost votes compared to 2019: the GL lost a seventh of its votes, while the PvdA lost only a fiftieth. GreenLeft became the largest party in university cities, those in the West of the country (like Amsterdam, Utrecht and Rotterdam), but also those in the North (Groningen), East (Nijmegen) and South (Maastricht). Two thirds of its voters come from urban areas. The PvdA also got about 60% of its support from those urban areas. Still, the Labour Party did relatively well in rural areas in the North-East of the country where it was often the second party after the BBB.

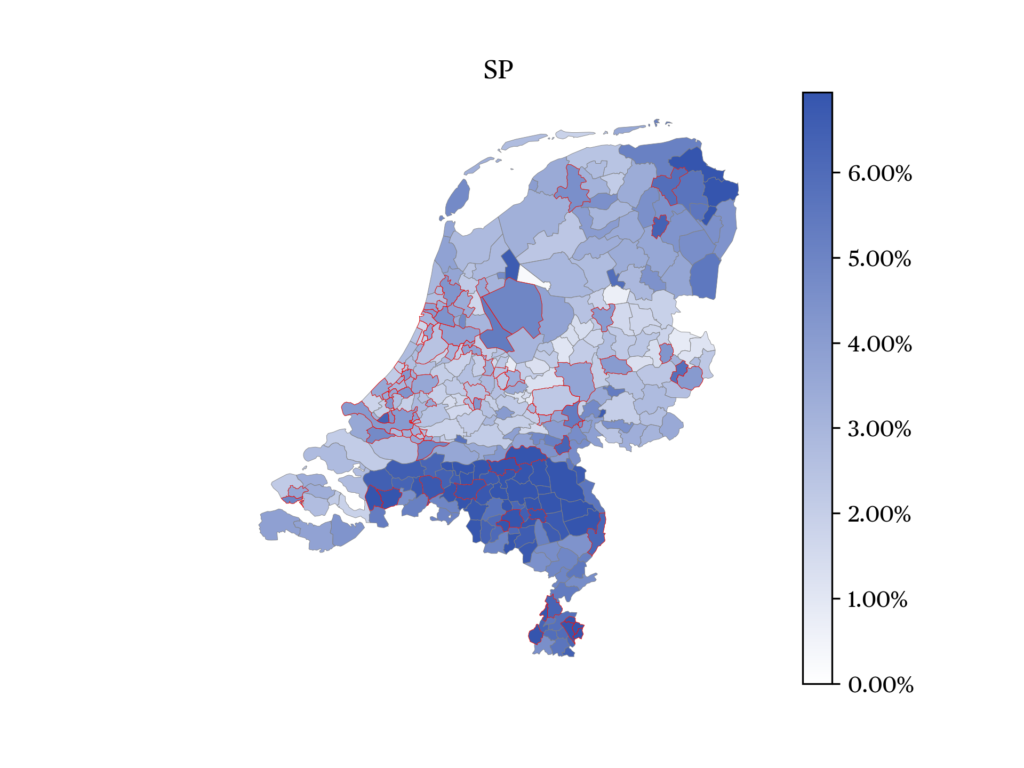

Two other parties stand to the left of this pair, one of which is the Socialist Party. The Socialists used the rising energy prices as an opportunity to criticize the government’s neo-liberal economic policy. Before the elections, it organized a demonstration calling for the nationalization of energy companies. Despite this, the SP lost thirty percent of its voters. In total, this was the seventh time in eight years that the SP lost votes in nation-wide elections. Its voters are relatively evenly distributed between urban and rural areas.

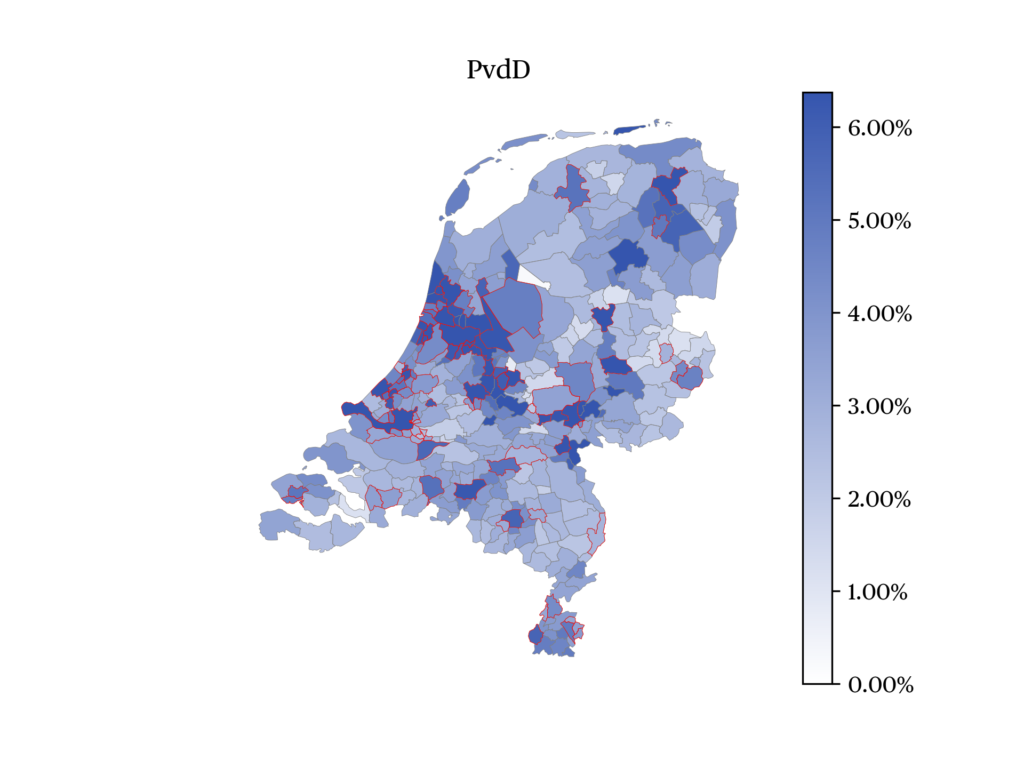

The Party for the Animals has a broad (in its own words, ‘planet-wide’) agenda where it connects the global climate crisis and the state of the environment in the Netherlands with the treatment of animals in factory farming. The party benefitted from the campaign’s focus on the future of farming, nitrogen policy and the natural environment. In the end, it performed well in these provincial elections, winning 10% more votes than in 2019. Its electorate skews highly urban with two thirds of their voters living in highly urban areas.

The Right-wing Opposition

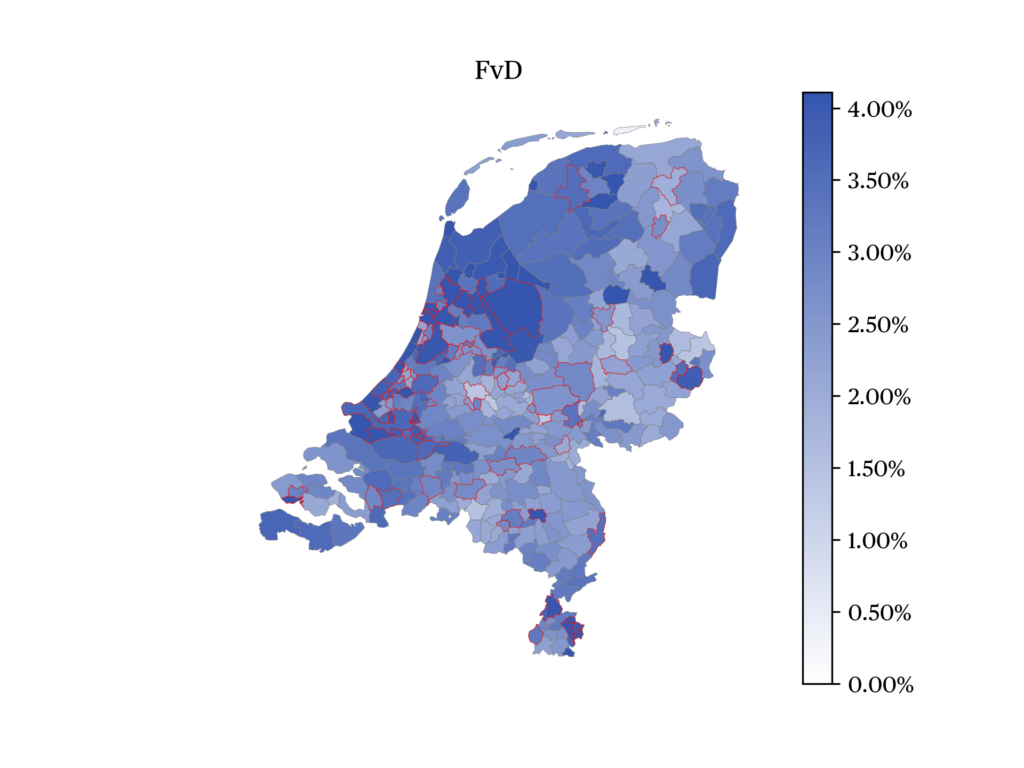

To the right of the government, there are four parties: the radical right-wing populist Freedom Party (Partij voor de Vrijheid, PVV, I&D), the more moderate JA21 (Yes21, ECR), the more extreme Forum for Democracy (Forum voor Democratie, FVD, ECR) and the conservative protestant Political Reformed Party (Staatkundig Gereformeerde Partij, SGP, ECR). The FVD was the big winner of the 2019 Provincial elections where, after holding only two seats in the lower house elections two years before, it had suddenly become the largest party (Otjes 2021a). The FVD had started out as a Eurosceptic party to the right of the VVD, but during the election night of the 2019 Provincial elections, its leader Thierry Baudet had flirted openly with far-right rhetoric (talking of ‘a boreal world’, echoing words of Benito Mussolini and Jean-Marie Le Pen). This victory speech started a process of decomposition that would take four years to be completed. Former allies of Baudet, in particularly those elected to the Senate, left the party because of his use of far-right rhetoric, his unwillingness to sanction the antisemitism in the party’s youth wing, his comparing the Corona rules to the German occupation of the Netherlands and the lack of support to Ukraine after the Russian invasion. The party campaigned on a collection of conspiracy theories regarding the Corona vaccine, the World Economic Forum, the War in Ukraine and nitrogen policy. Compared to the 2019 elections, the FVD was decimated: the party lost eighty percent of its support compared to 2019. Of its 2021 voters, there were more who did not vote than those who turned out to vote in the provincial elections. Its supporters, like those of all radical right-wing populist parties in the Netherlands, are relatively evenly distributed between more urban and rural areas.

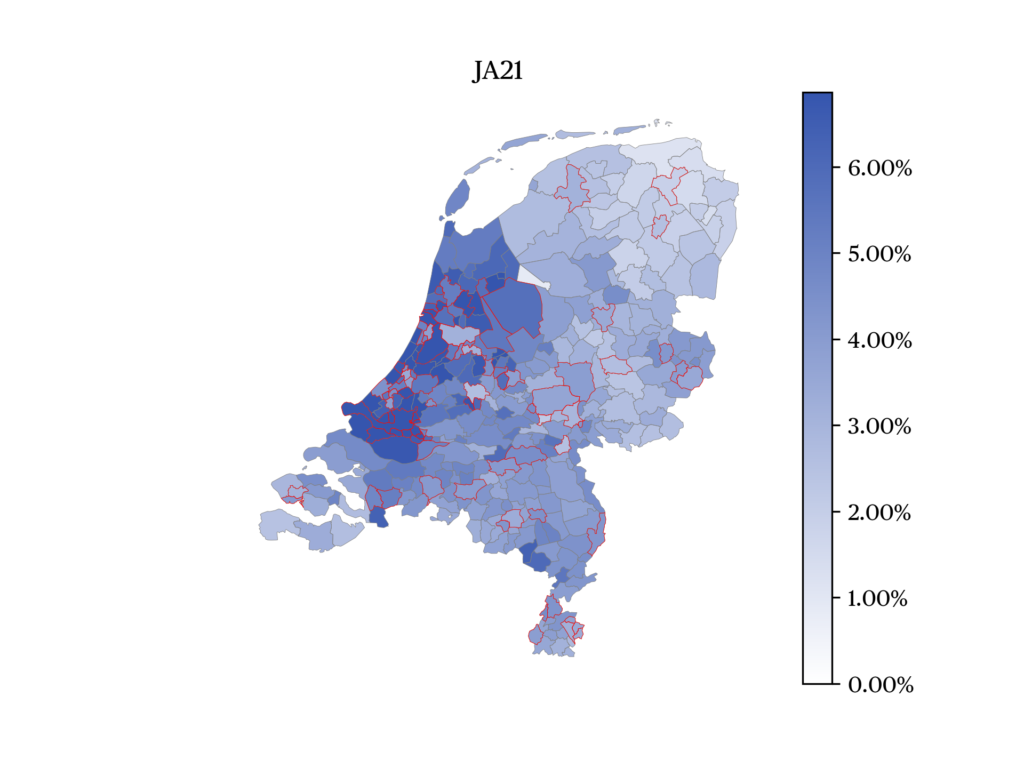

One split from FVD was JA21, a party aimed to keep the original conservative liberal course of FVD between the mainstream right and the radical right (Spierings et al. 2021): for instance, this party is Euroskeptic but not opposed to Dutch membership of the EU; it is opposed to the government policies regarding nitrogen, but does not deny that nitrogen negatively affects biodiversity. On the latter issue, JA21 has drafted a common policy white paper with BBB. While the party did not participate in the 2019 elections, it did hold a Senate group of seven members all originally elected for the FVD, and, as such, was the fifth-largest group in the Senate. The party won four percent of the votes, much less than it needed to keep its seven senators and well below the score it had hoped for in view of the unpopularity of the government, the cabinet’s inability to restrict the entry of refugees and the decline of the FVD.

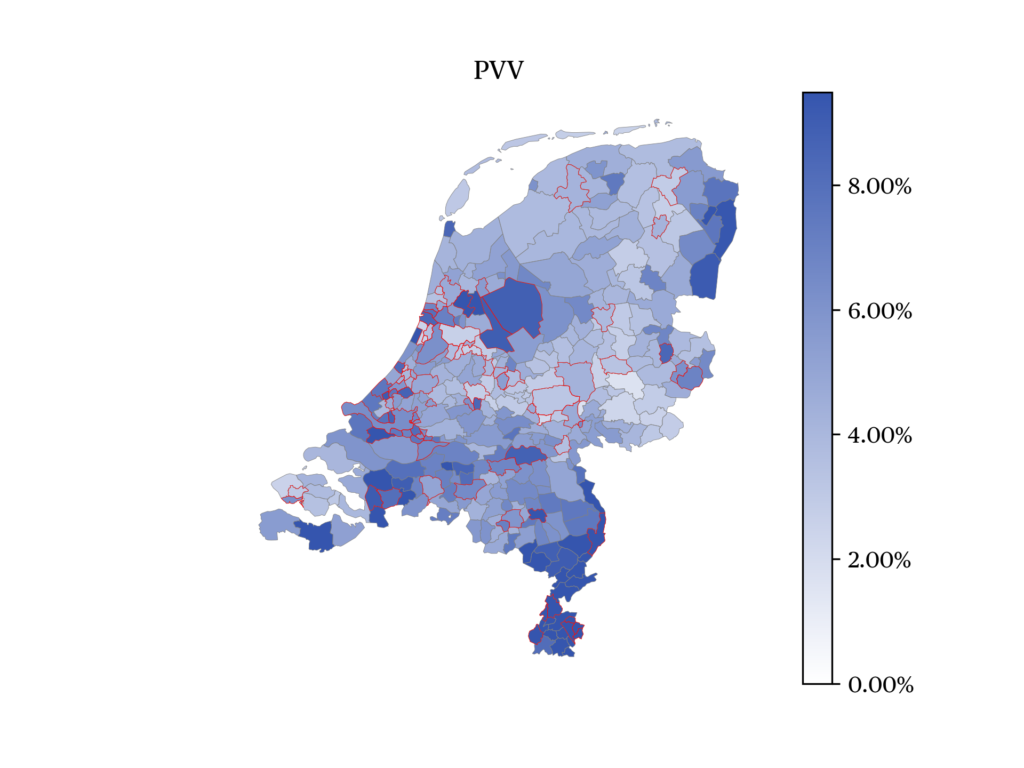

Before the campaign, the PVV appeared to be in a good position: the collapse of the FVD to its right, an unpopular government to its left and a consistent message of opposition to price increases, to the nitrogen policy of the government, to immigration, “islamisation” and EU membership. But despite the party polls leading up to the elections indicating that the PVV would expand its electorate, it eventually lost a sixth of its vote share compared to 2019. A sizeable chunk of its voters went to the BBB.

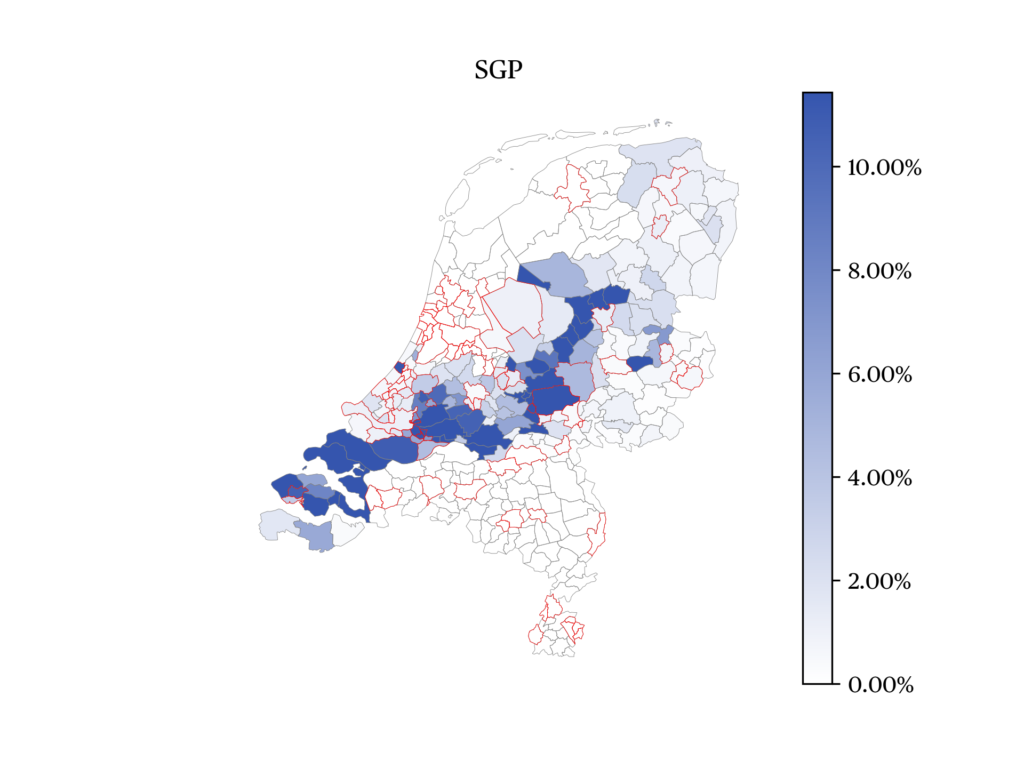

The SGP is a stable star in the firmament of Dutch politics. The Christian party combines conservative positions on moral issues (opposition to abortion, euthanasia, mandatory vaccination etc.) with a constructive attitude towards the government (Otjes 2021c). Therefore, despite the fact that it is quite right-wing on most issues, the government often relies on it for support. In a landscape of extreme change, the SGP was stable at 2.5%.

The Centrist Opposition

In addition to the opposition parties to the left and the right of the government, there are three opposition parties that, due to their centrism or single-issue nature, cannot be classified in either: the pro-European party Volt (G-EFA), the pensioners’ party 50PLUS (EPP) and the alliance of regional parties (Onafhankelijke Politiek Nederland, OPNL, G-EFA).

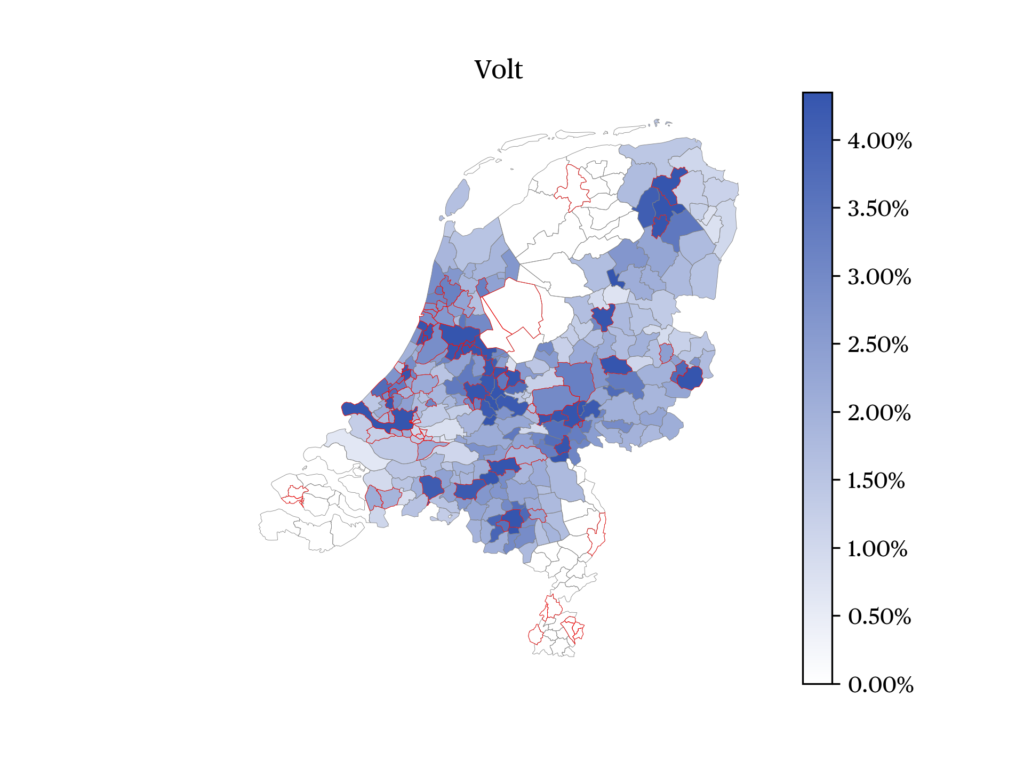

Volt won three seats in the lower house in 2021. The party is characterized by its pro-European orientation, support for nuclear energy and commitment to good government. In 2022, the party lost a seat due to “transgressive behaviour” of one of its MPs (Otjes & De Jonge 2023). However, due to organizational problems, it only participated in elections in eight out of twelve provinces. Volt did well in university cities, becoming the third-largest party in Wageningen and Nijmegen. Overall, it won three percent of the votes. Volt’s support skews extremely urban with 70% of its support coming from urban areas.

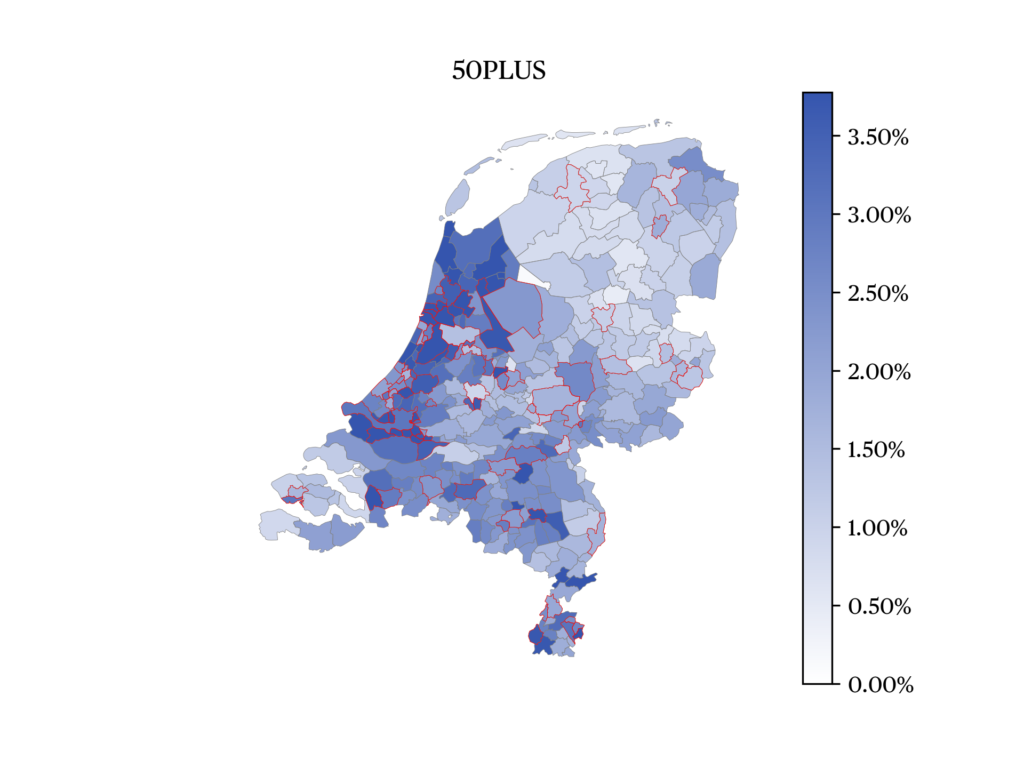

50PLUS had seen a rocky last two years. The party had lost all but one of its seats in the 2021 national election and, a few months after the elections, that one MP left the party. The political leadership thus shifted to one of its two senators. In the meantime, the government worked on a new pension law, which 50PLUS strongly opposed because it no longer ensured fixed benefits for private sector pensions. The party only lost forty percent of its votes, likely due to its opposition to the pension reform.

The last party represented in the Senate is the alliance of regional parties, Independent Politics Netherlands (OPNL). The alliance brings together parties from different provinces that are not aligned with national political parties. The most prominent of these is the Fryske Nasjonale Partij (Frisian National Party, FNP, G/EFA) that desires greater autonomy for Frisia, a Northern province with its own language. In six other provinces, its allies have won seats, which allows it to keep its single Senate seat. In the Senate, this Senator speaks out in favour of the interests of regions outside of the populated West of the country and the autonomy of small-scale subnational governments.

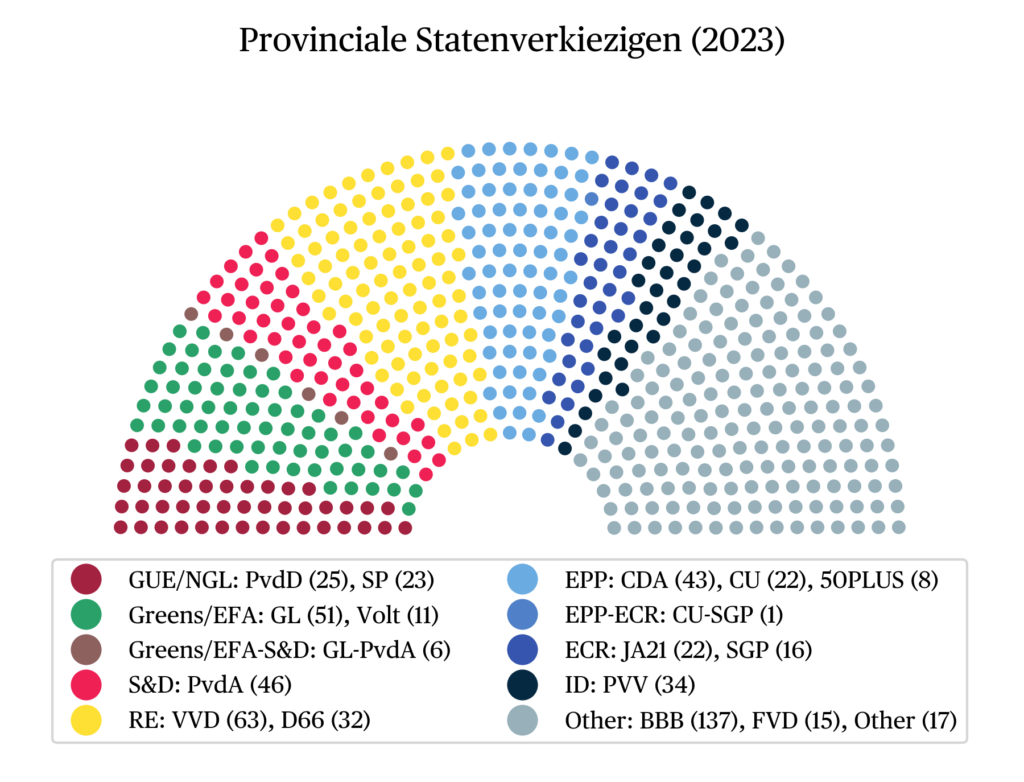

The Senate Results

The Senate is elected indirectly by the Provincial Councils more than two months after their own election. In addition to the Provincial Councils, special electoral colleges representing the three Caribbean islands (which are Dutch municipalities that do not belong to any province) and Dutch citizens residing abroad also participated. 5 These elections use a system of pure PR with no threshold. The votes of the different electors are weighted by the number of citizens they represent.

| VVD | Liberal Party | Renew | Conservative liberal | 12 | 10 | |

| FvD | Forum for Democracy | ECR | Radical right-wing populist | 12 | 2 | |

| CDA | Christian-Democratic Appeal | EPP | Christian-Democrat | 9 | 6 | |

| GL | GreenLeft | G/EFA | Green Left | 8 | 7 | |

| D66 | Democrats 66 | Renew | Social liberal | 7 | 5 | |

| PvdA | Labour Party | S&D | Social-democrat | 6 | 7 | |

| PVV | Freedom Party | I&D | Radical right-wing populist | 5 | 4 | |

| SP | Socialist Party | GUE/NGL | Socialist | 4 | 3 | |

| CU | ChristianUnion | EPP | Christian-social | 4 | 3 | |

| PvdD | Party for the Animals | GUE/NGL | Deep green | 3 | 3 | |

| 50PLUS | EPP | Pensioners’ interests | 2 | 1 | ||

| SGP | Political Reformed Party | ECR | Christian-conservative | 2 | 2 | |

| OPNL | Independent Politics Netherlands | G/EFAc | Regionalist | 1 | 1 | |

| BBB | Farmer-Citizens Movement | – | Rural populist | – | 16 | |

| JA21 | Yes21 | ECR | Radical right-wing populist | – | 3 | |

| Volt | G/EFAd | Pan-European | – | 2 | ||

| a Senate Seats; b Think in Dutch but Equal in Turkish; c Affiliation of the member party FNP c Affiliation of the German Volt MEP | ||||||

Like any PR system, a form of remainder seat division is necessary. The Netherlands uses the system of largest averages. As the results can be predicted before the elections, this allows for tactical voting: by voting for another party than they were elected for, a councilor can ensure that another party would gain an additional seat compared to the system when everyone votes for their own party without costing their own party a seat.

While it is tempting for political scientists to understand these elections in game-theoretical terms, they are actually about trust: trust between coalition parties, trust between opposition parties, trust between the coalition and opposition parties and trust within parties. Compared to the situation where everyone would vote for their own party, three parties lost a seat (BBB, PVV and GL) and three parties won one (CDA, CU and Volt). In this exchange, we can see trust (or lack thereof) at multiple levels. Firstly, the coalition was able to expand its seats from the expected 22 to 24. In this effort, D66 and VVD helped CDA and CU. This shows the despite the problems in the coalition, the trust between the parties is still sufficient to take on these risks. However, we note that D66 members refused to vote CDA and that a little ‘train’ had to be arranged: D66 councilors voted for the VVD who in turn let its councilors vote for the CDA. This does show where the distrust in the coalition is strongest.

Due to the order of the remainder seats, the first party that would have to pay for a potential additional seat for the coalition would be the SGP. In the Senate elections, the CU supported the SGP sufficiently that they would not have to drink this cup of poison. This shows the deep bond of trust existing between two parties that, while they have taken very different positions in daily politics 6 and stand on different sides of the coalition-opposition divide, share a common Calvinist ideology. PVV and BBB both ended up with one seat less.

On the left, two things happened: The PvdA and GL were both expected to get remainder seats. Neither of them was really in a position to help the other. In order to make sure that other parties were less likely to ‘steal’ the PvdA’s remainder seat, all Provincial Councilors in Zeeland elected on the joint list of the PvdA and GL voted for PvdA. This was mostly a symbolic good-will gesture. Yet, one GL provincial councilor in South Holland, who had been in conflict with her party before, did not vote for her own party but for Volt. Because of all these votes not being cast for GL, the party lost one senator compared to the expectations and Volt gained one.

All in all, the coalition got 24 seats in the 75-person Senate (see Figure f). After the Senate elections, GL and PvdA formed a common group with 14 senators. This was the second group after BBB with 16 senators. This meant that the government had the option to form a majority (of 38) with either GL/PvdA or BBB. Mathematically, the coalition could also form a majority without these two (for instance with PVV, SGP, Volt, JA21, FVD and the alliance of regional parties), but that is unlikely given the ideological diversity of those parties.

Conclusion

The Netherlands has become known as one of the most unstable electorates in Europe, and in 2023 it did not disappoint, with an electoral volatility of 29%. This is the highest electoral volatility in the Senate since the institution of the current electoral system in 1983, about twice as much as the average between 1983 and 2023. With the BBB, a new political force mobilizing rural dissatisfaction vaulted into first place. This came mostly at the cost of a far-right party that had placed first in 2019, the radical right-wing populists and centre-right governing parties.

On election night, the Dutch government knew that it did not have a majority in the Dutch Senate, as it had been the case for eleven of the last thirteen years. Due to the strongly bicameral nature of Dutch parliamentarism, the government would have had to strike deals with opposition parties to get its policies adopted. The main question at the time was whether the government would do so by seeking support from the BBB or from GL/PvdA. In the end, this question was never answered, since a month after the new Senate was installed, the cabinet fell due to tensions between the VVD and the CU on migration policy. The 2023 Provincial elections now appear to have been a dress rehearsal for the 2023 National elections that will be held in November. Although in terms of party leadership a lot has changed since the Provincial elections, the dynamics are likely to be similar: the Liberal Party and a combined list of GreenLeft and Labour Party will compete for becoming the largest party and nominating the next Prime minister. The BBB, as well as Pieter Omtzigt’s new party New Social Contract (NSC), will instead seek to mobilize voters that are dissatisfied with business-as-usual in The Hague.

Finally, on an academic note, we observe there is surprisingly little research about voting behaviour in the Dutch provincial election (with Binnema and Vollaard 2021 as an exception). It is an open question to determine to what extent provincial or national themes influence voters in their decision. Journalistic reporting and commercial polling suggest that both aspects are relevant; however, an academic analysis of the relative importance of the evaluation of provincial and national governments, as well as general ideology and positions on specific provincial themes, is still missing.

The data

References

Adviescollege Stikstof Problematiek (2020, 8 June 2020). Niet alles kan overal.

Arter, D. (2023). ‘Bigwig hatred’ and the emergence of the first Scandinavian agrarian‐populist party. Scandinavian Political Studies. Published online ahead of print.

Binnema, H., & Vollaard, H. (2021). The 2019 provincial elections in the Netherlands: the Rise of Forum voor Democratie after a heavily nationalized campaign. Regional & Federal Studies, 31(3), 433-446.

Coalition agreement (2021). Omzien naar elkaar, vooruitkijken naar de toekomst Coalitieakkoord 2021 – 2025 VVD, D66, CDA en ChristenUnie.

De Lange, S. (2018, 26 October). Zeeuws en Nederlander. Over de vertegenwoordiging van burgers uit de provincie in het Haagse. Raad vor het Openbaar Bestuur, Weblogbericht.

De Lange, S., Van der Brug, W., & Harteveld, E. (2023). Regional resentment in the Netherlands: A rural or peripheral phenomenon?. Regional Studies, 57(3), 403-415.

Huijsmans, T. (2023). Place resentment in ‘the places that don’t matter’: explaining the geographic divide in populist and anti-immigration attitudes. Acta Politica, 58(2), 285-305.

Kester, J. (2021, 8 April). Mark Rutte blijft ‘onacceptabel’ als premier, wel minder weerstand tegen samenwerking met VVD. EenVandaag. Online.

Lievisse Adriaanse, M. (2023, 16 March). Waarom BBB óveral groot is: dit is niet alleen de overwinning van het platteland. NRC.

NOS (2023, 15 March). Bekijk hier alle uitslagen van de Provinciale Statenverkiezingen. NOS.nl. Online.

Otjes, S. (2021a). The fight on the right: what drives voting for the Dutch Freedom Party and for the Forum for Democracy? Acta Politica, 56(1), 130-162.

Otjes, S. (2021b). Parliamentary Election in Netherlands, 17 March 2021. BLUE, 1(1), 52-60.

Otjes, S. (2021c). Between “eradicate all false religion” and “love the stranger as yourself”: how immigration attitudes divide voters of religious parties. Politics and Religion, 14(1), 106-131.

Otjes, S., & de Jonge, L. (2023). The Netherlands: Political Developments and Data in 2022: A New Cabinet Facing New and Old Challenges. European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 62(1).

Otjes, S., & Voerman, G. (2020). The Netherlands: political developments and data in 2019. European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook, 59(1), 261-271.

Raad van State (2019). PAS mag niet als toestemmingsbasis voor activiteiten worden gebruikt. Raad van State. Online.

Spierings, N., Lubbers, M. & Sipma, T. (2021). PVV, Forum en JA21 maken samen radicaal-rechts groter. Sociale Vraagstukken.

Voerman, G. & De Jonge, L. (2023). De BoerBurgerBeweging: een agrarische belangenpartij met populistische trekjes. De Hofvijver 13(141).

Vossen, K. (2015). Agrarian parties in the Netherlands: the Plattelandersbond and the Boerenpartij. In Strijker, D., Voerman, G., & Terluin, I. (Eds.). Rural protest groups and populist political parties. Wageningen Academic Publishers. (pp. 22-38)

Notes

- The Dutch government selects these itself.

- E.g., ammonia would be captured in stables.

- The child survived.

- The Senate cannot autonomously set tax levels, only approve tax bills passed through the House.

- The voting weights (based on population) of the electoral colleges together amass 0.33 seat.

- CU takes centre-left positions on environmental, economic and migration issues while the SGP is right-wing on these.

citer l'article

Simon Otjes, Provincial and Senate elections in the Netherlands, Nov 2023,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue