Regional election in Murcia, 28 May 2023

José Miguel Rojo

Predoctoral Fellow at the University of MurciaIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

José Miguel Rojo

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

On May 28th, regional elections were held in twelve of the seventeen autonomous communities of Spain. In addition, on that day the members of all city councils across the country (more than eight thousand) were elected, including the forty-five councils of Murcia.

The context

Murcia’s 10th Legislature, which ended last May, was in a convulsive stage and prone to controversy. On top of four major crises that hit this community during the period 2019-2023 (the floods of autumn 2019, the anoxia and ecological crisis of the Mar Menor also in autumn 2019, the coronavirus and the economic and energy crisis due to the war in Ukraine) the region was subject to significant political instability. In March 2021, the coalition government, then formed by the Popular Party (PP, EPP) and Ciudadanos (Cs, RE) broke down and the minority coalition partner decided to file a motion of no confidence together with the PSOE (S&D) against President Fernando López Miras. That motion of no confidence included the coordinator of the liberal Ciudadanos party as a candidate for the presidency, despite the fact that this formation came third in the 2019 elections and only had 6 of the 45 seats that make up the Regional Assembly. The motion of no confidence ended up being a great failure: part of the Ciudadanos MPs dissociated themselves from the initiative and supported the continuity of the Popular Party in power. In exchange, they kept their seats in the government, although their party had considered the coalition broken. This generated a great debate throughout the country on the allegations of political transfugitivism. However, the weakness of the Popular Party was evident. It had just lost the elections to the PSOE in 2019 — by a few hundred votes and for the first time since 1991 —, had obtained the lowest number of seats since 1987, had to form the first coalition government of democracy in the Region of Murcia and, in addition, found itself with the need to shore up its legislative agenda with a somewhat uncomfortable third partner: the radical right of Vox (ECR), a party that participated in the majority of support for the government, conditioning some measures (such as requesting greater parental control over the educational talks given in schools), although without being part of the executive.

The regional political situation continued to worsen as within the Vox party, a series of splits took place which turned 3 of its 4 deputies in the 10th Legislature into “free verses”. The Popular Party had to negotiate with the former members of the radical right their vote against the motion of no confidence, since it was essential that they did not vote in favor of the initiative for change. In return, one of the deputies formerly integrated in Vox and now expelled from the formation became part of the government as head of Education and Culture. In this way, the Region of Murcia became the first autonomous community in Spain in which a person linked to the radical right assumed government responsibilities.

The failure of the motion of no confidence was not only in parliamentary terms. Public opinion also received it negatively, especially the electorate of Ciudadanos, which did not understand the turn of his party. According to data from CEMOP (Murcian Public Opinian Study Center) in its Spring Barometer of 2021, 59.5% of those interviewed thought the presentation of this motion was bad or very bad, but, what is more, 67.7% of Ciudadanos voters in 2019 thought the decision of their party was bad or very bad (Crespo et al., 2021: 29). From this political storm in 2021 (which had effects in other areas of the country, causing the advance of the elections in the Community of Madrid), the PP was improving its electoral expectations, the PSOE was lowering its support and Ciudadanos began to drift towards an extra-parliamentary status. Meanwhile, Vox was growing despite its internal problems, and one must remember that the radical party won the general elections of November 10, 2019 in the province of Murcia, being the only peninsular territory in the country where it was the first force.

The campaign

Beyond the analysis of the legislature that preceded the May 28th elections, it is worth highlighting the prominent role played by national issues in the electoral campaign, which almost made the problems of each territorial area invisible. These elections, commonly described as “second order” (Montabes, Alarcón and Trujillo, 2023), were used by the opposition parties to the government of the Socialist Pedro Sánchez as a sort of first round to force snap elections. The figure of Pedro Sánchez himself became the focal point of a negative campaign from PP and Vox.

In Murcia’s case, the big question that hovered over the campaign was not whether the right (PP+Vox) would manage to overcome the left — something that all the polls took for granted. The key question was whether the Popular Party could govern alone or whether it would inevitably need the support of the radical right. The Popular candidate and current president, Fernando López Miras, ran for the elections with the slogan “The necessary majority”. López Miras refused to return to governing in coalition with any party — the experience had not been very good according to him — and called for a solo government to achieve more effective decision making. It was known, however, that the goal of 23 seats (needed for an outright majority in the Regional Assembly) was difficult after the reform of the Murcian electoral system carried out in 2015: a reform that lowered the electoral threshold present since 1982 from 5% to 3% and eliminated the five constituencies, moving to a single constituency system that facilitates the proportional distribution of seats and the entry of minority parties. For its part, the radical right focused its campaign on insecurity and support for agriculture in the face of the environmental regulations imposed on the Mar Menor and by Agenda 2030. Mar Menor’s environmental crisis has been one of the major issues of regional politics in recent years, reaching a cultural battle level (tension between the interests of agricultural companies and the conservation of the lagoon, tension between different models of life and society). The Popular Party was in the middle of two poles on this issue, between the environmental positions of the left and Vox’s extreme defense of agriculture.

The results

Electoral turnout reached 63.25% compared to 62.3% in 2019. The turnout in 2023 is very close to the figures reached in 2015 (63.57%), but far from those obtained at the beginning of this century (in the elections of 2003 the turnout was 70% and in those of 2007 it reached 68%). This slight increase in turnout compared to 2019 – perhaps due to the mobilization capacity that the nationalization of the campaign could have had – does not eliminate the fact that Murcian citizens vote less in their autonomic elections than in general elections. A few months later, on July 23, and despite the exceptional nature of the date, the participation in the elections to the General Courts in the Region of Murcia was 70.78%. Something similar happened in 2019. On November 10 of that year, 66.2% of the census turned out to vote, despite the fact that it was a repeat election (on April 28 of the same year another general election had been held).

The low turnout figures — that in recent years characterize the regional elections in the Region of Murcia — may be connected to a general perception of limited possibilities for change, or the non-exceptional nature of the elections, i.e., understanding that there is not much at stake, the incentives to participate decrease (Manzanera Román, 2020; García Escribano, 2015). If we perform an analysis of participation by municipality, we find that those of smaller size are also those in which voters turned out to vote to a greater extent — exceeding 90% participation in 3 cases. The turnout in the capital (66.31%) was somewhat higher than the regional average, but the second most important city in the Region of Murcia in terms of population and economy, Cartagena, is the second municipality with the lowest turnout, 60.17%. This is a significant result to explain some phenomena of territorial cohesion and identification, assuming the existence of a Cartagena/Murcia cleavage that has its translation in the party system (with the birth of a local party, Movimiento Ciudadano, which promotes the creation of a province for Cartagena and the separation, therefore, of the province of Murcia).

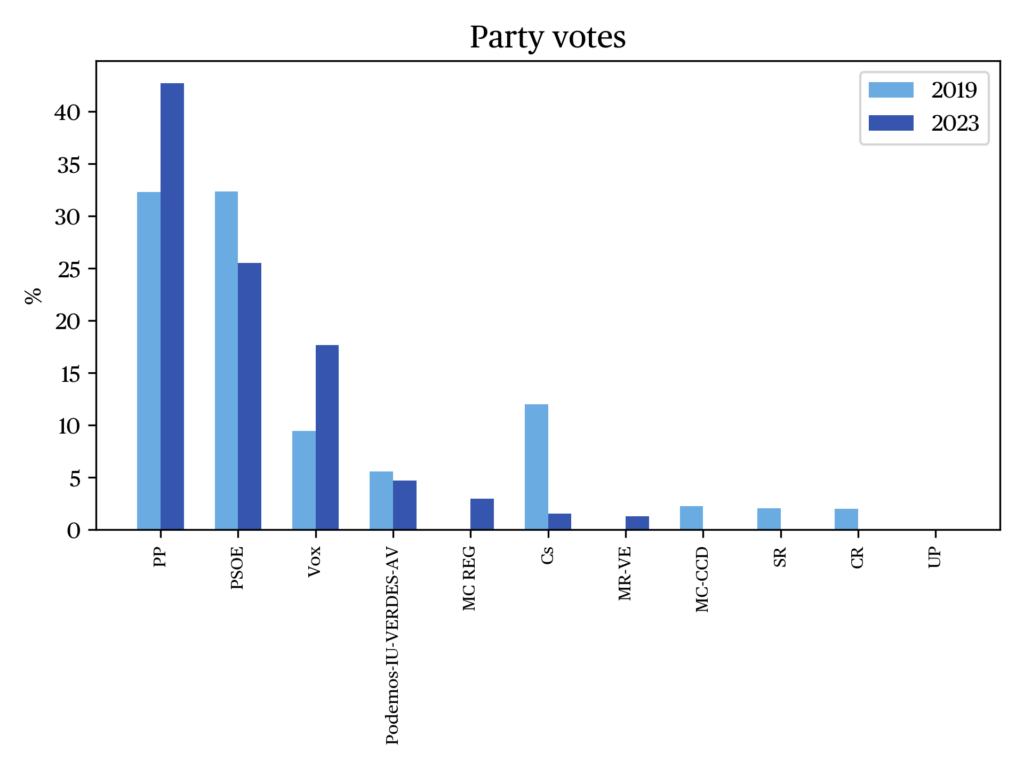

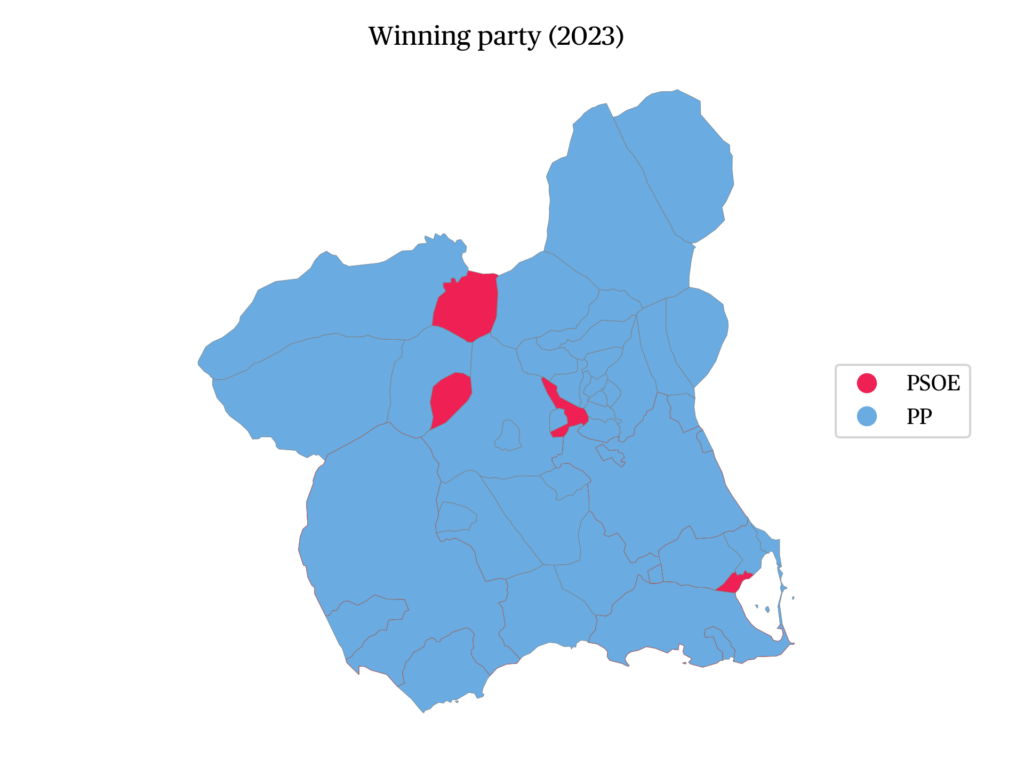

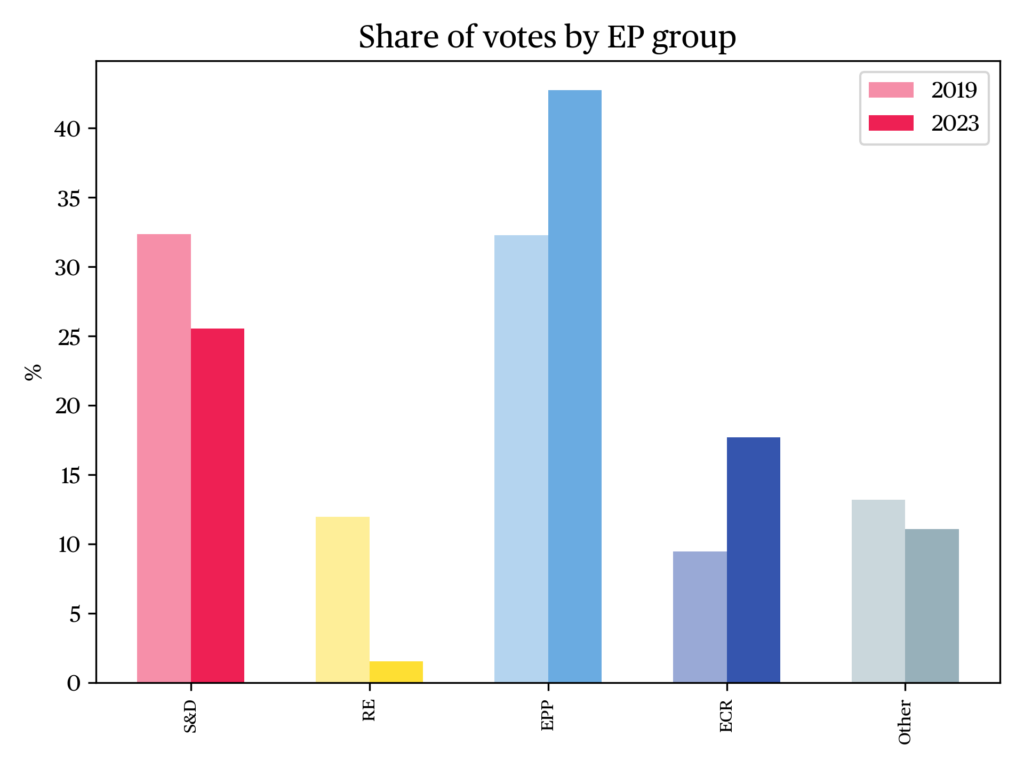

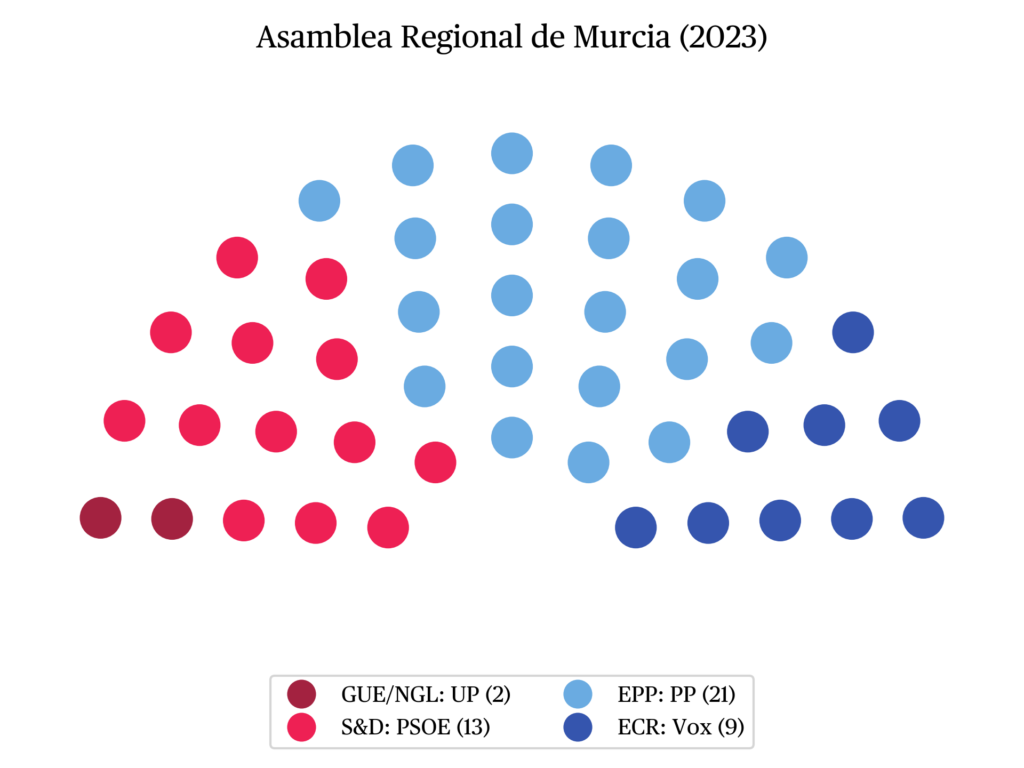

As for party results, the moderate right wing represented by the Popular Party obtained a clear victory, with 43.22% of the votes cast (293,051). This amounted to 21 seats, only two less than the outright majority and more than the sum of the left-wing parties (PSOE and Podemos-IU-AV). The Popular Party obtained 17 points more than the second party, the PSOE, which obtained 175,505 votes and 13 seats. Compared to 2019, the Popular Party won 5 more seats, was again the most voted force and increased its results by more than 81,000 votes. The growth of the government party can also be seen in terms of the territorial distribution of its victory: it was the winning party in 41 of the 45 municipalities that make up the Region. As for the PSOE, it lost 4 seats and more than 37,000 votes, a hard result for a party that has not governed the Region of Murcia since 1995.

On its side, Vox managed to improve its 2019 results: it went from 4 MPs to 9 and its vote share reached 17.93% in 2023 (8.43 point increase compared to four years earlier). This is the highest percentage obtained by VOX in the set of autonomic elections held in the country last May 28. The growth of the radical right in Murcia is consolidated. In fact, the Region of Murcia is, together with Almería, Vox’s great stronghold. Of course, after arriving first at the November 10 general elections, expectations could have been higher.

Why does the radical right triumph among a large part of the Murcian electorate? To answer this question it is useful to read authors such as Crespo and Mora (2022), who have investigated this question in depth. What distinguishes the Vox voter in the Region of Murcia, and gives the party an added element with respect to other motivations shared with the country as a whole, are the nativist-based issues. Crespo and Mora (2022) show that there is a positive correlation between voting for Vox and the percentage of resident population born in Morocco and that respondents who vote for VOX justify their vote with nativist arguments. The Region of Murcia, known as “the orchard of Europe”, is an area closely linked to the primary sector, with a productive model that attracts a large number of migrant labor, especially of Moroccan or sub-Saharan origin. This creates a differential social context with respect to other areas of Spain and, it could be argued, that this exceptionality becomes a possible explanatory factor of the vote for the radical right.

Finally, the alternative left, represented by the Podemos-Izquierda Unida-Alianza Verde candidacy, maintained its parliamentary representation (2 seats), a result that can be considered satisfactory when compared to other regions. For example, in Madrid or in the Valencian Community, Podemos-Izquierda Unida ceased to have representation as of May 28. Despite this, the space significantly reduced its support from 49,738 votes in 2019 (then Izquierda Unida and Podemos concurred separately and these votes result from the sum of the 36,486 votes of Podemos and the 13,252 votes of the “Cambiar la Región” candidacy, which included Izquierda Unida and Anticapitalistas) to 32,173 in 2023. Podemos’ candidate in these elections, María Marín, starred in one of the most remarkable moments of the campaign in the only televised debate between all the candidates. By refusing to leave the set to give her space to the representative of Más Región-Verdes-Equo, the party with which Podemos competed in coalition in 2019 and with which the propaganda spaces and debates were to be distributed as determined by the electoral authority, she forced the suspension of the debate in full live. It was never repeated nor was another one held again, thus becoming the first debate between candidates in the democratic history of Spain to be suspended once it had begun.

Regardless of the results by party, the balance of power between the ideological blocs consolidated the hegemony of the right in the Region of Murcia. PP and VOX accounted for 61.25% of the votes and the left (PSOE and Podemos-IU-AV) 30.7%. This reproduces a voting structure that has characterized Murcia since the late nineties, with the only particularity that now the right appears divided in two – something that did not happen until 2015 with the appearance of Ciudadanos and more intensely since 2019 with VOX. Therefore, the electoral behavior of Murcian citizens is stable with hardly any room for transfers between parties of different ideology, if we perform an aggregate analysis.

Faced with such a stable scenario and virtually immovable preferences, the only novelty of the elections could have come from the hand of the Cartagena Citizen Movement (MC). This party, of a diffuse ideological nature (catch all) and with a populist type of leadership, intended to reach the Regional Assembly to continue denouncing the discrimination that, according to them, Cartagena suffers because of Murcia, the capital. The party obtained more than 20,000 votes (2.99%) and was about to overcome the 3% barrier and get a seat. So much so that during a good part of the vote counting it got it. In Cartagena, the party obtained 19.59% of the votes, a remarkable result which affected the vote share of major parties: the PP obtained 35.93% of the vote in Cartagena and the PSOE 17.59%, both results below those obtained in the region as a whole. Considering these percentages, one can also note that MC has a greater impact on the socialist electorate than on the popular electorate, although it snatches votes from all parties.

The beginning of the new legislature

With the results now final, the Parliament was constituted on June 14. At the beginning of July a first investiture vote was held. The Popular Party candidate had not closed a pact with Vox and took advantage of his speech to claim the legitimacy he had to govern alone after his resounding victory (he alone had more seats than PSOE and Podemos-IU-AV together), an argument that did not convince the radical right. The investiture did not go ahead and during the summer months everything came to a standstill. When it seemed that the Region was doomed to repeat the elections, PP and Vox reached a pact — in parallel with Núñez Feijóo’s first attempt to investiture in the Congress of Deputies — by which the candidate of the radical right, José Ángel Antelo, a former basketball player, would become the new vice president of the Region of Murcia, assuming competences in security, emergencies and urban planning. On September 14, the third López Miras government took office. In addition to the new vice president, Vox also took over the infrastructure department. However, the party failed in its claim to control the department of agriculture and water, a strategic issue for the radical right in Murcia.

The data

References

Crespo Martínez, I., García Escribano, J. J., García Palma, M. B., Garrido Rubia, A., Manzanera Román, S., Mayordomo Zapata, C., & Sánchez-Mora Molina, M. I. (2021). Realineamiento electoral. Barómetro de primavera 2021. Barómetros de la Región de Murcia. Online.

Crespo Martínez, I. & Mora Rodríguez, A. (2022). El auge de la extrema derecha en Europa: el caso de Vox en la Región de Murcia. Política y Sociedad, 59(3).

García Escribano, J. J. (2015). Las elecciones autonómicas de 2015 en la Región de Murcia. Cuadernos Manuel Giménez Abad, 10: 149-64.

Manzanera-Román, S. (2020). Participación, abstención y momento de decisión del voto en las elecciones autonómicas de mayo de 2019 en la Región de Murcia. In Crespo Martínez, I. & J. J. García Escribano (eds.), ¿Cómo vota el electorado murciano? Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch.

Montabes Pereira, J., Alarcón González, F. J., & Trujillo, J. M. (2023). Las elecciones municipales de 2023 en España: la consolidación de una dinámica de bloques. Más Poder Local, 53 : 88-105.

citer l'article

José Miguel Rojo, Regional election in Murcia, 28 May 2023, Jun 2024,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue