Regional election in Saarland, 27 March 2022

Marius Minas

Research Associate at the Chair for Western Government Systems at the University of TrierIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Marius Minas

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

The Saarland state election in 2022 was the first after Olaf Scholz (SPD) was elected chancellor in the 2021 federal election and Friedrich Merz (CDU) was elected federal party leader. While the election was in any case a tough challenge for the Saarland Christian Democrats, who had occupied the Saarbrücken State Chancellery for 22 years and were in danger of losing it according to pre-election polls (Infratest Dimap 2022a), it was also seen in the public debate as the first test of public opinion for the two newly elected figures at the federal level. The fact that the different levels in the German federal political system are interdependent is not a new phenomenon (Detterbeck and Renzsch 2008; Minas 2021). Elections can certainly influence other elections. However, people and specific issues set their very own trends in the states and the federal government, as this election clearly illustrated.

While politics in the federal capital Berlin in the spring of 2022 were mainly driven by the war in Ukraine and its effects, with foreign, security, trade and defence policy being primarily federal competences, one thing above all was true of the outcome of this state election: the focus of the Saarlanders in this election was on genuinely regional issues and personalities, despite the extensive presence of the war (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2022; John 2022: 6). As will be demonstrated in the further course of this analysis, this election seemed unusually detached from the usual logics of interdependencies between federal and state politics.

1

Therefore, contrary to the widely discussed public assumption, it was only suitable to a very limited extent as a barometer of sentiment for federal politics and as a predictor for the state elections in Schleswig-Holstein and North Rhine-Westphalia in May, both of which shaped their own dynamics through state-specific issues and personalities (for more on this see: Drewes (2022) and Wurthmann (2022) in this volume). The following analysis explains the election result of the Saarland state election in 2022 on the basis of different, commonly used perspectives of electoral research and particularly addresses socio-demographic, geographic, party-political and economic factors as well as the role of leadership candidates.

“The Saarland faces a mountain of problems” (Kirch 2022a: 7), which are also compounding each other. In addition to the persistent fiscal weakness, the demographic development is a cause for concern in what is already the second-smallest federal state. In the last 25 years, the Saarland has lost almost 100,000 inhabitants (currently approx. 983,000). In addition, there is the ongoing structural change in the economy. Traditionally, (heavy) industry has formed the economic backbone of the state. While jobs in the coal mining industry disappeared years ago, the automotive and steel industries, which are also not considered climate-friendly, are now under great pressure (ibid.) to address these problems of economic development and job security.

The result of this state election was therefore at the same time the decision on which policy should be used to pursue these goals and the no less important answer to the question of who the Saarlanders trust to lead this policy.

Election results in perspective: The Saarland sees red

Election results in figures

In 2022, 51 MPs were elected in three constituencies in Saarland by means of list voting according to pure proportional representation. All German citizens who are over 18 years of age, have had their main residence in Saarland for at least three months and have not been explicitly excluded from voting have the right to vote (Kollmann 2020: 361).

2

Each eligible voter has exactly one vote, which can be used to elect a party or electoral group whose candidates are on fixed lists. The parties or electoral groups have the option of submitting a district list in each of the three constituencies and, in addition, a state list for the whole of Saarland as an election proposal, on which they can distribute their candidates and determine their own order (ibid.: 363f). Seats are allocated on the basis of the number of votes cast according to the maximum d’Hondt method, on condition that at least five per cent of the votes are obtained (five per cent clause). Of the 51 MPs in the Landtag, 41 are determined via the district lists and 10 via the state lists.

3

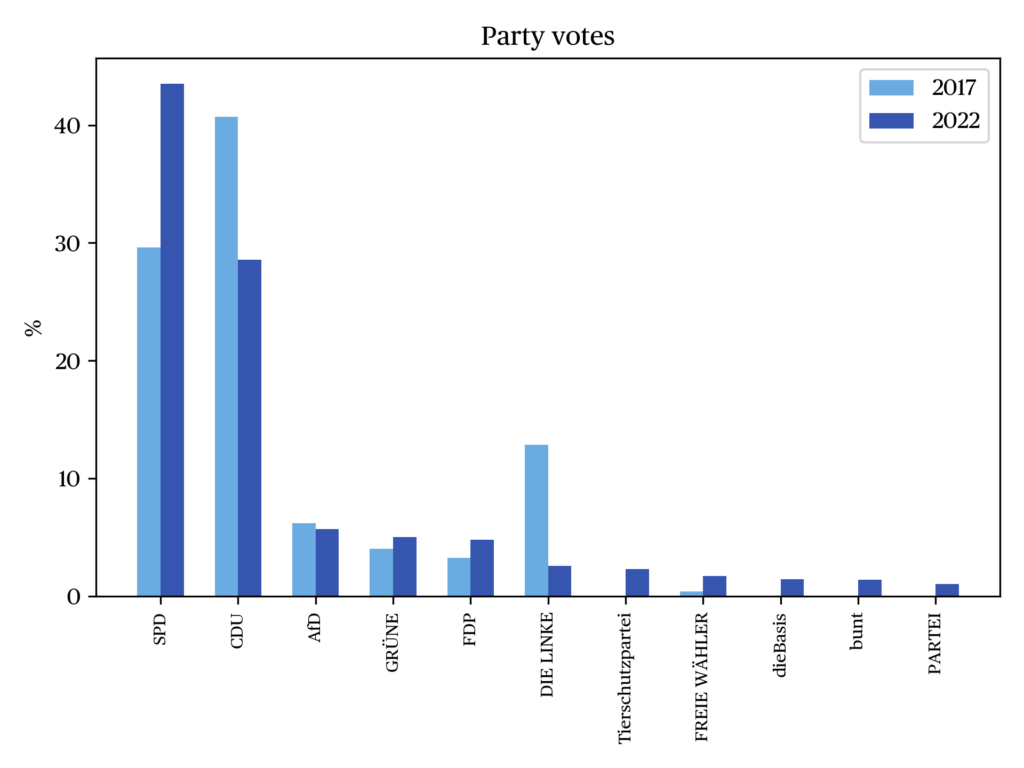

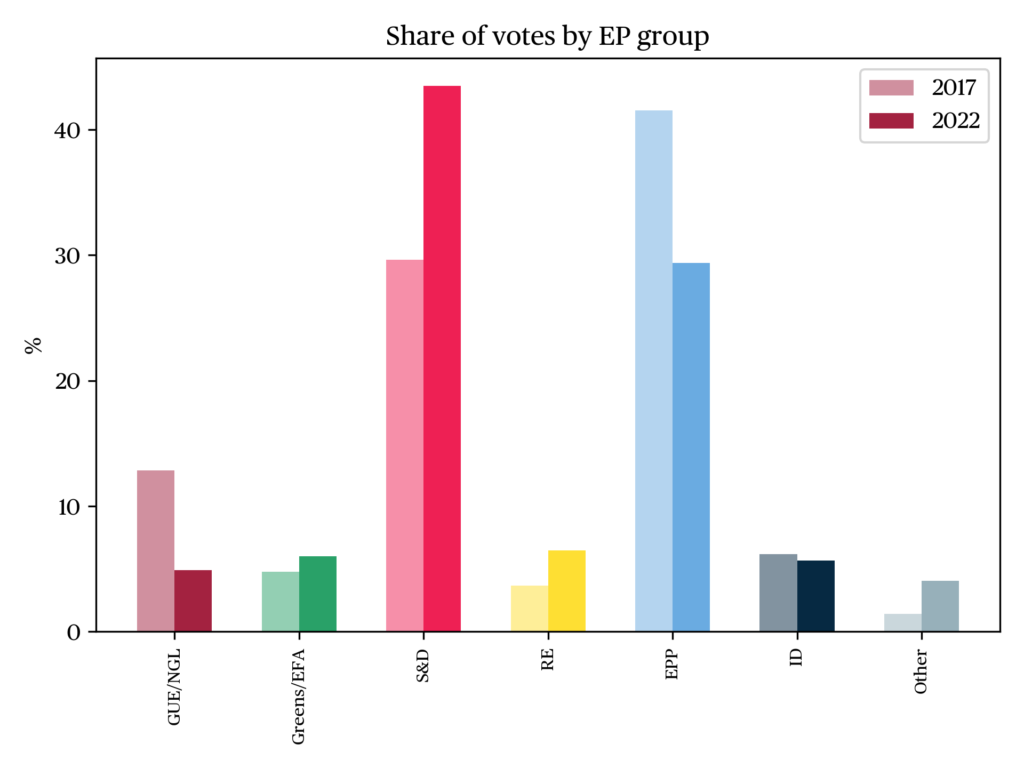

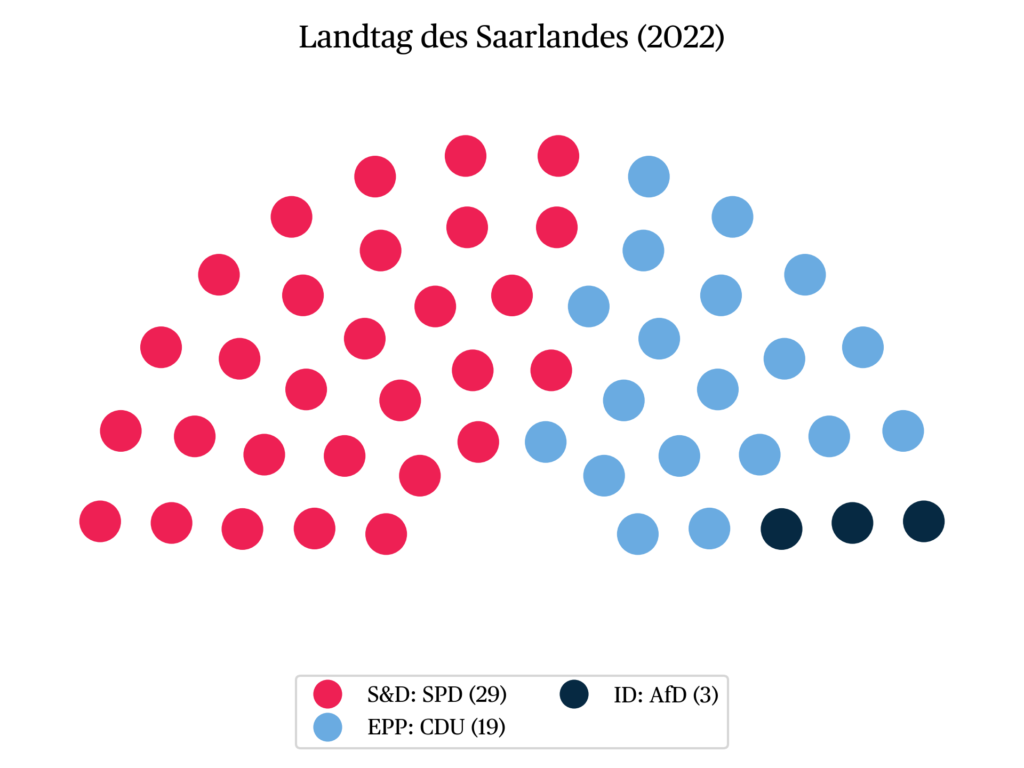

As can be seen from the figures in the “data” panel, and taking into account the results of the State Election Commissioner (2022), the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD; S&D) emerged as the clear winner — more so than predicted by the poll results (Infratest Dimap 2022a) in the months leading up to the election. With 43.5 per cent of the vote, it won 29 of the 51 seats to be allocated in the Landtag, thus achieving Germany’s only absolute majority in a Land parliament. The Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU; EPP) obtained 28.5 per cent of the vote on election day, giving it 19 seats in the state parliament. The Alternative for Germany (AfD; ID) scored 5.7 per cent and thus received the remaining three seats — all other parties and voter groups thus missed out on entering parliament. Bündnis90/Die Grünen (EFA) failed to meet the threshold with 4.99502 per cent. In absolute numbers, the party fell 23 votes short of entering parliament (Kirch 2022b: B1). The Free Democratic Party (FDP; RE) also failed to enter parliament for the third time in a row, with 4.8 per cent of the vote. The otherwise comparatively strong party in this federal state, Die Linke

4

(GUE/NGL) missed its re-entry into the state parliament with a result of 2.6 per cent. The small and very small parties, such as the Tierschutzpartei

5

(Animal Protection Party), FREIE WÄHLER

6

(RE), die Basis

7

(The Basis), bunt.saar

8

(Colourful Saar), Die Partei

9

(The Party) and all the other voter groups and parties

10

also failed to win a seat in the Saarland state parliament.

Compared to the 2017 state election, among the parties represented in the new state parliament, only the SPD was able to improve in terms of the results it achieved. It increased its share of the vote by +13.9 percentage points. Alliance90/The Greens (+1.0 %) and the FDP (+1.5 %) also recorded a slight increase. While the AfD only suffered a relatively small decline in votes of -0.5 per cent, the CDU (-12.2 per cent) and Die Linke (-10.3 per cent) recorded a severe decrease in their share of the vote. The ‘other parties’ climbed in their total by +6.5 percentage points from a total of 3.4 per cent in 2017 and reached a combined 9.9 per cent of the electoral vote in 2022. Looking at the format of the parties at the parliamentary-governmental level, the four-party parliament of the last legislative period (CDU, SPD, Die Linke, AfD) became a three-party parliament consisting of SPD, CDU and AfD. It can thus be stated that with the elimination of the Left PartGy in the Saarland state parliament, the polarisation in this institution has also decreased compared to the previous legislative period.

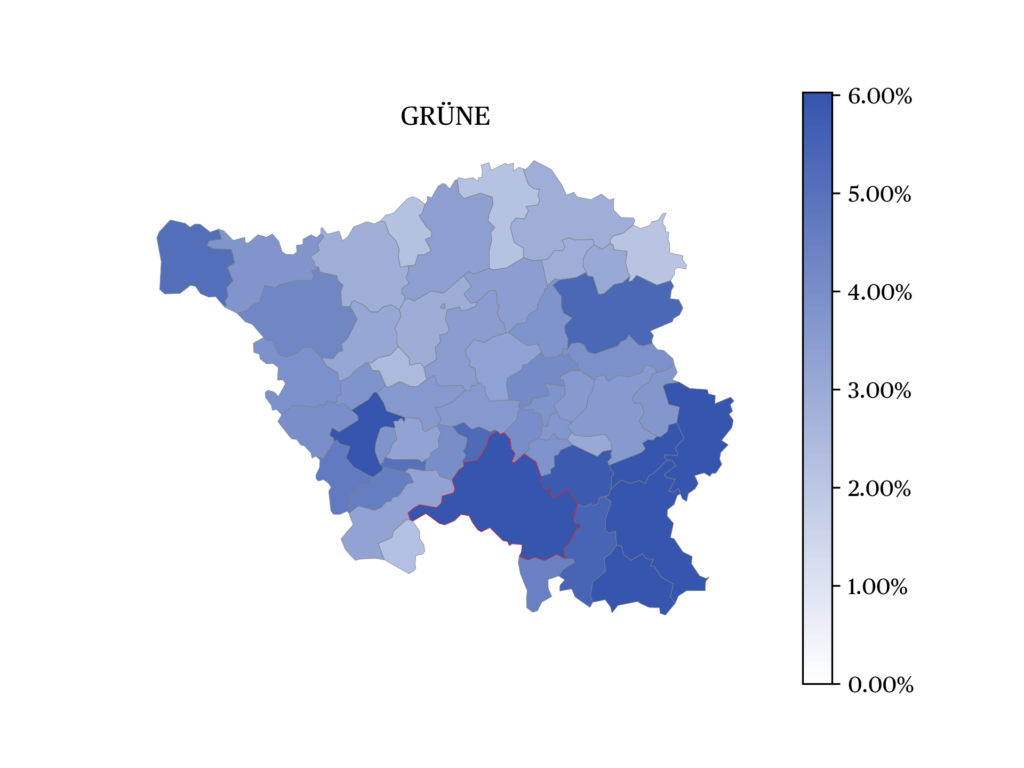

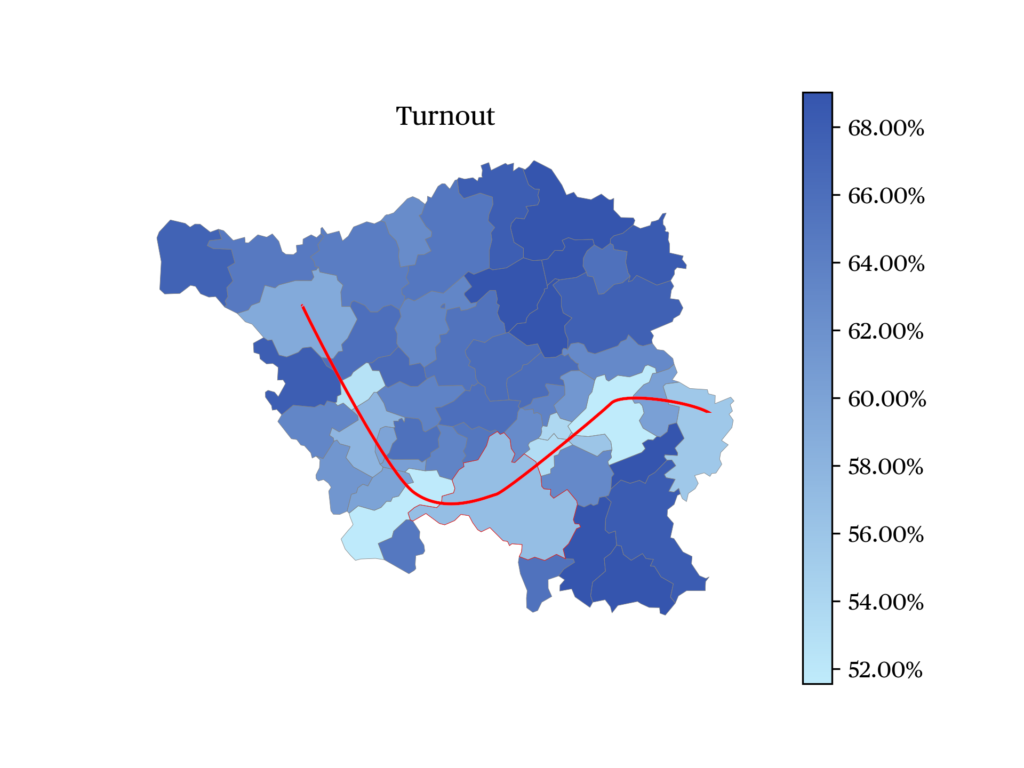

Out of 746,307 eligible voters, 458,113 went to the polls, resulting in a voter turnout of 61.4 % in 2022 (2017: 69.7 %). The proportion of absentee voters was 43.5 per cent (SR.de 2022). Figure 3 shows the voter turnout in the individual municipalities of the Saarland. It is interesting to note that voter turnout was high in rural areas — i.e. in the south-eastern part, in the centre as well as in the north of the state — while it was comparatively lower in urban areas — the reasons for this are discussed in the following sections. More than half of Saarland’s population lives in a V-shaped urban agglomeration (Loth 2021: 572; red line on Figure a). This comprises most of the populous cities in the state

11

and includes precisely those areas with the lowest turnout this year. This is a significant circumstance especially for the Greens, who can normally win comparatively more votes in urban areas.

The reasons for voting in favour of a party are manifold. In the following, the election result is therefore discussed from different perspectives. The analysis is based on the criteria of the established social-psychological Ann Arbor model, according to which so-called ‘relevant factors’ such as socio-demographic and geographical characteristics are temporarily preceded by ‘party identification’ and these in turn by ‘candidate’ and ‘issue orientation’ with a view to election day (for this, see: Campbell et al. 1960; Schoen 2009).

Socio-demographics and political landscape

Looking at Saarland’s socio-demographics, one key point in particular can be identified that suggests a significant connection with the election result. “Since the 19th century, the state’s economy has been dominated by heavy industry” (Loth 2021: 573), in particular the steel industry, coal mining as well as automobile manufacturing — i.e. precisely those economic sectors that are coming under pressure due to structural change. A differentiated look at the voting decisions of various relevant groups reveals that the SPD’s ‘landslide victory’ can be attributed above all to the fact that it was able to win back its former core voter clientele: Workers, senior citizens and people with lower levels of education (Kruse and Müller-Hansen 2022). Among blue-collar workers, 39 per cent voted for the Social Democrats (CDU: 20 per cent). 42 per cent of white-collar workers voted for the SPD (CDU: 25 per cent). Among public servants and the self-employed, only the CDU (37 and 36 per cent) had a lead over the SPD (31 and 27 per cent) (Infratest Dimap 2022c: 2). The age structure of voters also provides interesting insights into the election results: the SPD won significantly in all age groups. A significant movement compared to the 2017 election can be seen in the 60+ age group. A 20 percentage point increase propelled the SPD to 49 per cent in this cohort (CDU: 33 per cent) (ibid.), which in turn accounted for over 40 per cent of the electorate (John 2022: 9). The FDP and the Greens performed comparatively strongly among the young generation, so the trend of the previous Bundestag election continued there. The CDU came in at only 19 per cent — its weakest age cohort (Infratest Dimap 2022c; Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2022: 2). The AfD recruited its voters primarily among middle-aged men (ibid.). If one differentiates between voters according to their level of education, it can be summarised that higher levels of education were associated with a lower share of the vote for the Social Democrats. While 55 per cent of those with a lower secondary school degree voted for the SPD, only 37 per cent of those with a university degree did so. The CDU achieved a maximum of 30 per cent, regardless of the level of education. The Greens and the FDP in particular benefited from the SPD’s declining share of the vote in the more highly educated groups (Kruse and Müller-Hansen 2022).

Surveying the political map of Saarland reveals only a few nuances regarding the performance of different parties besides the completely red colouring (see the “data” panel) — i.e. the victory of the SPD in all municipalities of the state.

12

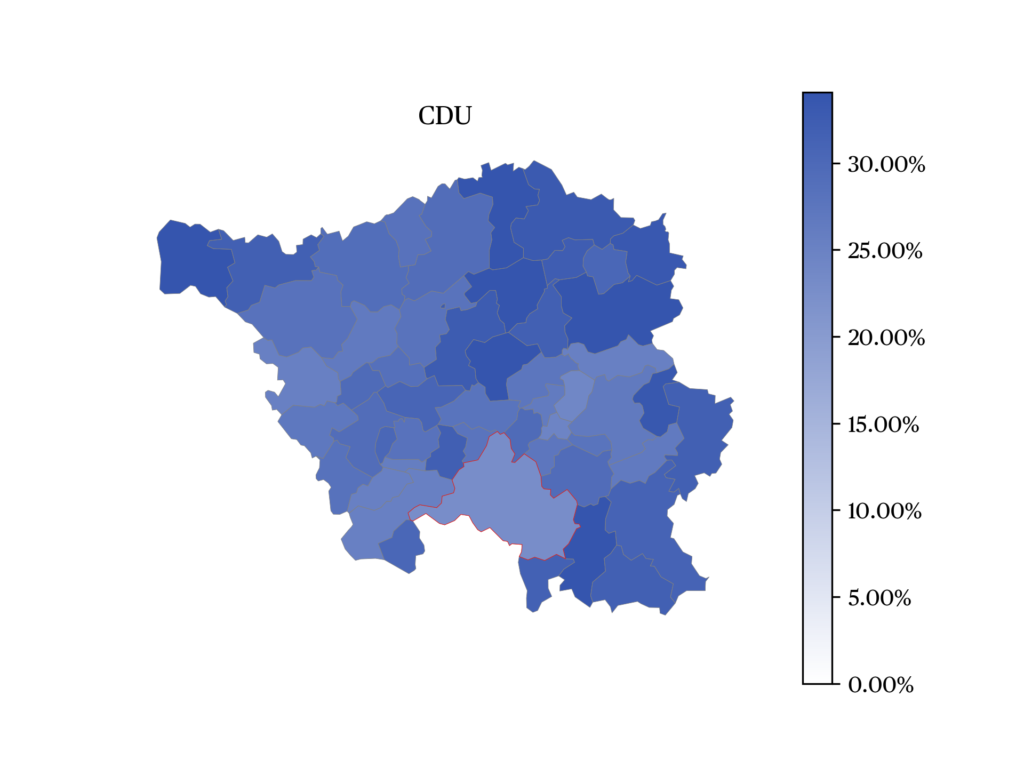

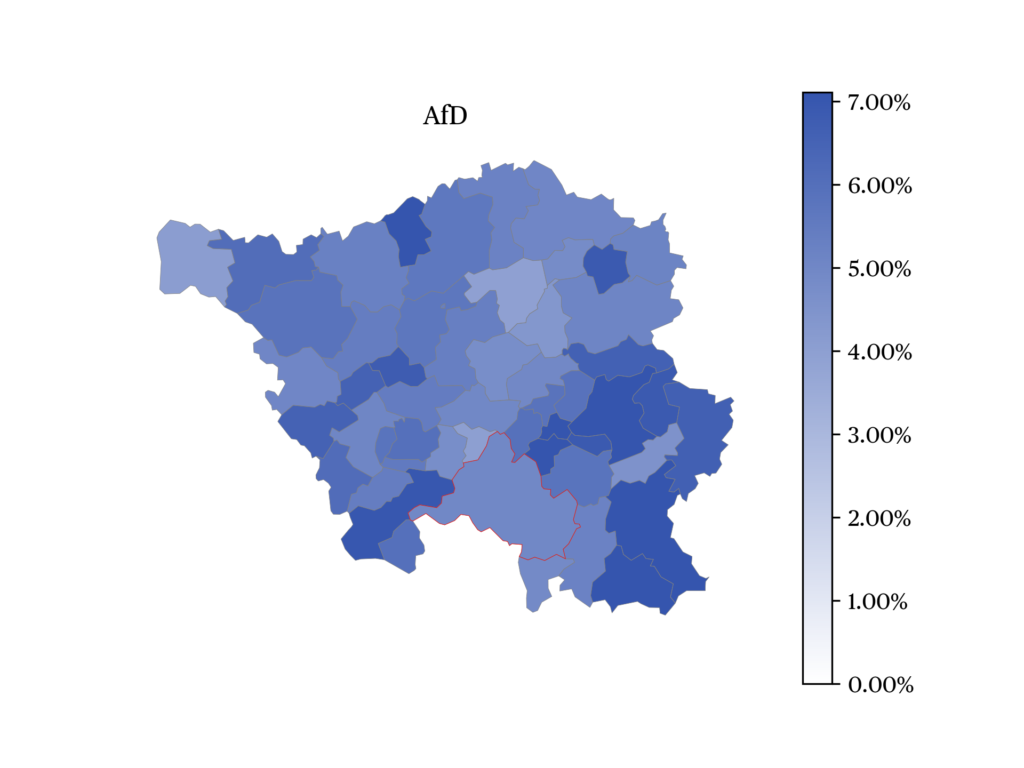

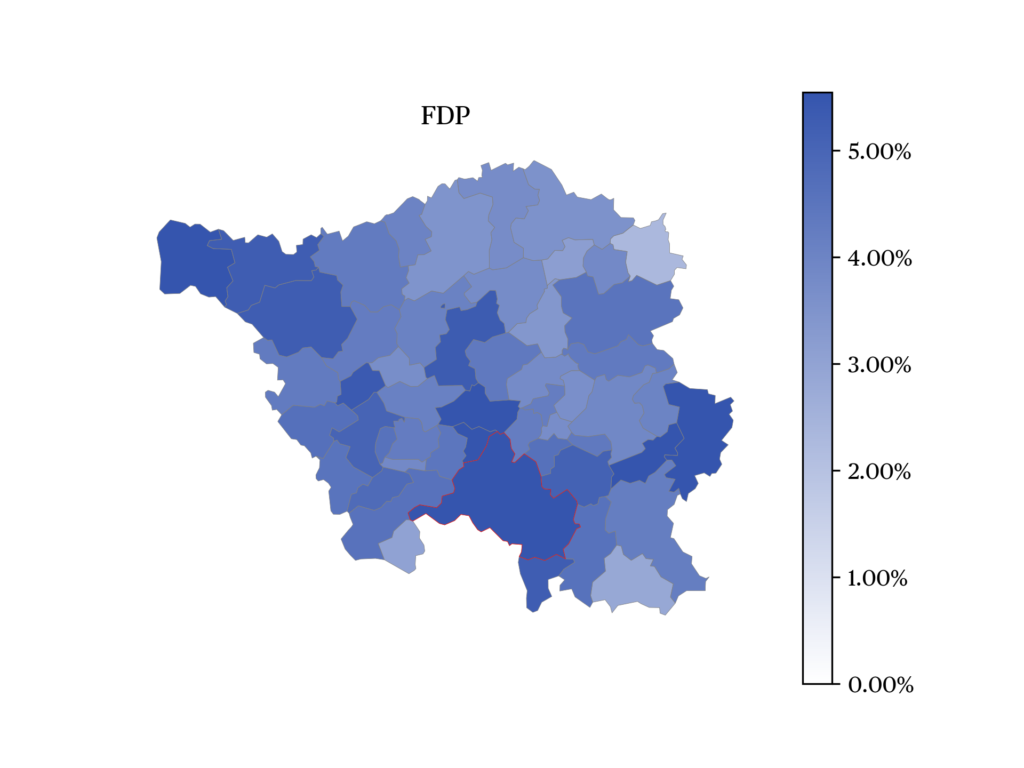

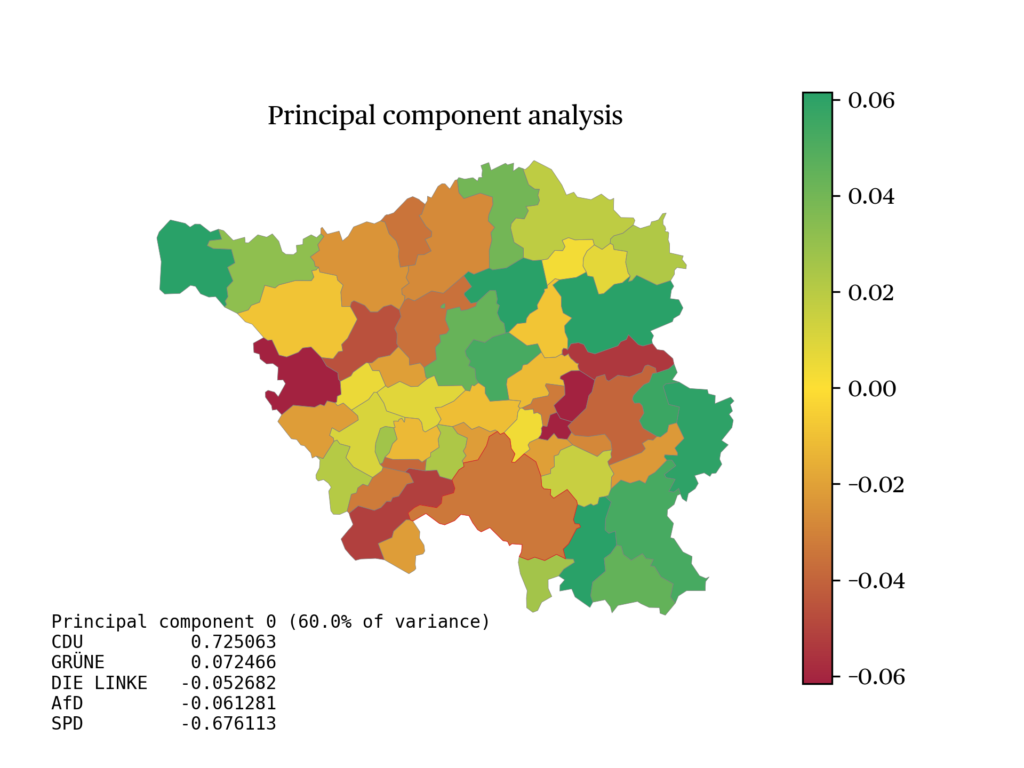

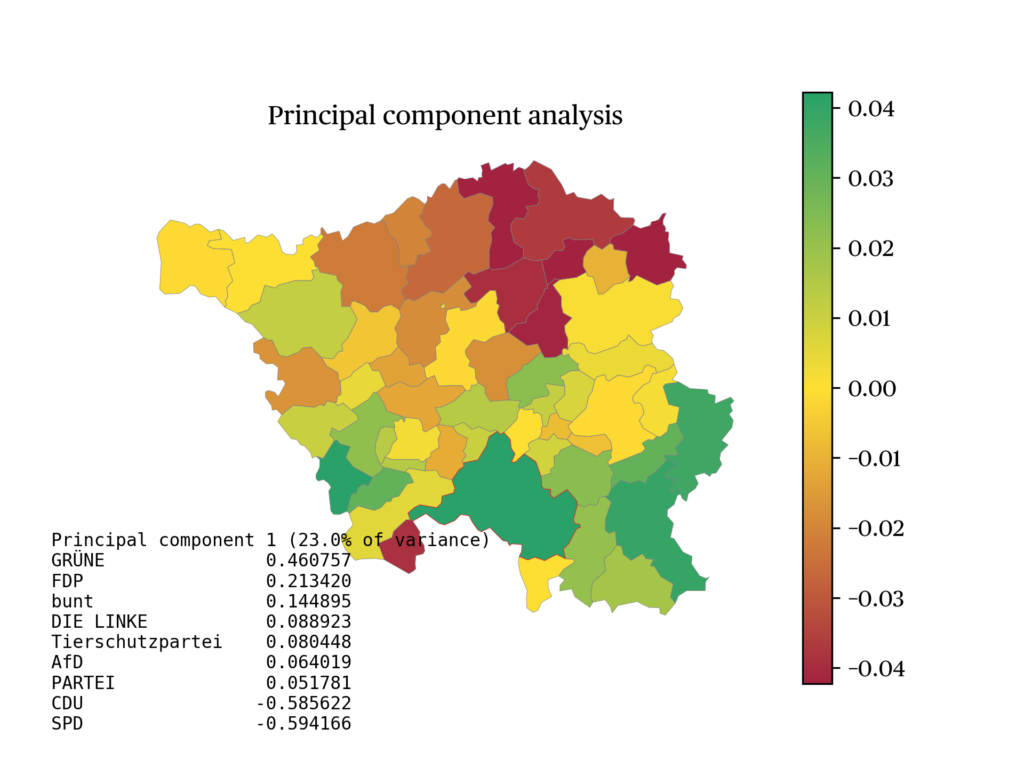

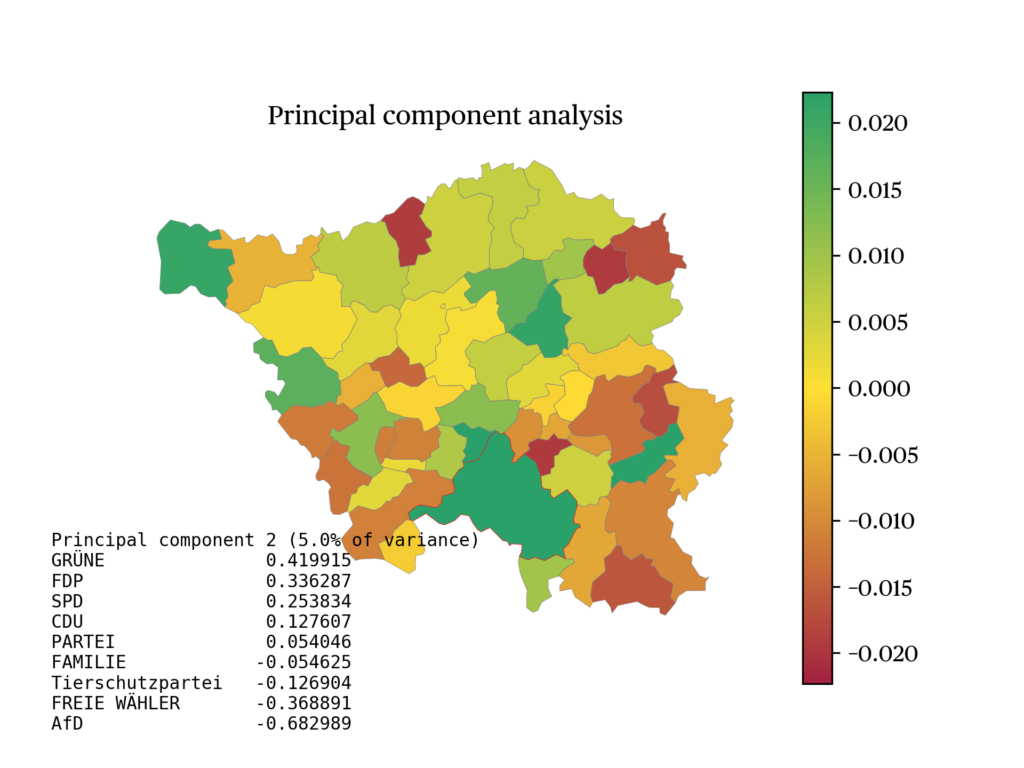

The CDU (Figure b) scored particularly well in the north-eastern constituency 3 (Neunkirchen) (30.7 per cent), but came in at only 25.5 per cent in constituency 1 (Saarbrücken). While its strongest municipalities were in the rural north-east of Saarland (see the principal component analysis in Figure f), the AfD (Figure c) performed well by its standards in the south-east, as well as in scattered municipalities throughout the state. In 15 rural municipalities, it was able to slightly improve its result compared to 2017, but declined everywhere compared to the federal election in the previous year. Interestingly, the Greens (Figure d) were also able to generate many votes by their standards in the south-east. In contrast to the AfD, however, they collected their votes mainly in the two most populous cities — Saarbrücken and Saarlouis (see also principal component analysis Figure f). In 42 of the 52 municipalities they were able to improve their state election result, albeit only marginally. Compared to its performance in the rest of the state, the FDP (Figure e) performed well in the municipalities close to the border with Luxembourg in the north-west, which can also be confirmed by the principal component analysis (Figure f). In all municipalities, the FDP improved compared to 2017, but in contrast to the 2021 federal election (11.5 per cent in Saarland), the result was very weak (John 2021: 3f).

The larger and the smaller parties

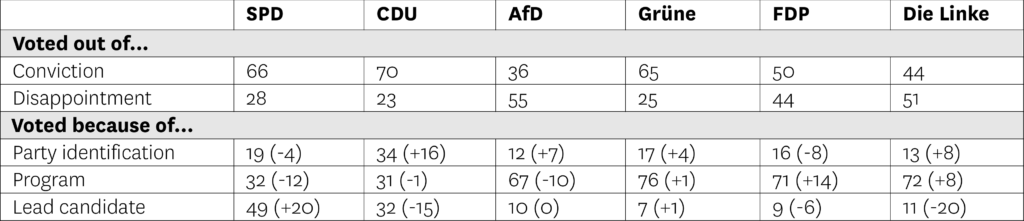

The next step in the analysis is to look at the role of the parties. Looking at figures h and i, a mixed picture emerges. While a smaller proportion of voters identified with the SPD and FDP than five years previously, the CDU recorded a strong increase in party loyalty, the Left and AfD a moderate increase and the Greens a slight increase.

13

However, the fact that these are only relative statements in reference to their own electorate is shown by the voters’ migration.

14

In addition to the strong support from its own electorate, the SPD was able to gain voters from all other parties, benefiting most from the CDU (approx. 32,000 voters) and from Die Linke (approx. 17,000 voters). The latter lost another 12,000 voters who did not go to the polls voluntarily this year; the CDU had to do without 19,000 voters. The AfD was also able to score with the former voters of Die Linke (4,000 voters) (Infratest Dimap 2022c).

The evaluation of the parties (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2022) shows an opposite picture compared to party loyalty. Here, the SPD was able to rise on the scale between -5 and +5 from 1.9 in 2017 to 2.1 and the FDP from -0.5 to -0.1 in the same period. All other parties recorded losses: CDU from 2.1 to 1.1; AFD from -3.6 to -3.8; Greens from -0.4 to -1.0; Die Linke from -0.1 to -1.8. The SPD benefited significantly more than the CDU from the quite positive perceptions of Saarlanders of the Grand Coalition

15

(Infratest Dimap 2022b). The poor performance of the Greens and the Left can be explained, among other things, by internal disputes that had been running through the parties since the year before. While this had little or no consequences for the AfD at the ballot box, the quarrels in Die Linke and Bündnis90/ Die Grünen led, among other things, to the founding of the electoral alliance bunt.saar, which won 1.4 per cent of the electoral votes — a particularly bitter circumstance for Bündnis90/Die Grünen, considering that they were only 23 votes short of entering the state parliament and that their internal disputes, which culminated in the inadmissible list in the 2021 federal election, were considered largely settled (John 2022: 8). Die Linke also had to pay for its internal strife by leaving parliament; in addition, however, the dispute with its figurehead Oskar Lafontaine played a special role, which will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

The personality factor

The role of personalities in the public debate as well as in everyday political life has been increasingly important for years (Karvonen 2010; Bittner 2011; Rahat and Kenig 2018). This circumstance is becoming increasingly evident especially in the context of elections and election campaigns. This state parliamentary election was no exception — on the contrary. The election campaign as well as the public debate surrounding the upcoming election were repeatedly conducted with enormous intensity about the personalities of the contesting parties.

As already mentioned, the focus was also on the former figurehead of the Left Party, Oskar Lafontaine. The former Minister-President of the Saarland (1985-1998) — at that time still under the Social Democratic banner — became the co-founder of the Left Party in 2007, which from 2009 onwards always achieved double-digit results in Saarland state elections, unlike its predecessor party, the PDS (Winkler 2018: 48). The strong position of the party, which otherwise performed rather poorly in the western states of Germany and was able to achieve good results mainly in the east, could so far be attributed not only to the socio-economic factors of the state but also to Oskar Lafontaine personally (Winkler 2018: 41ff; Hirndorf and Roose 2022: 4). The personal factor emerged all the more clearly when one looks at this year’s result of the Left Party and relates it to Lafontaine’s initially announced decision not to run for another legislative term (Saarbrücker Zeitung 2022), which ultimately culminated in his leaving the party (Kirch 2022c). After Lafontaine’s withdrawal from the party, the party finally found itself back where the predecessor party, the PDS, had been before Lafontaine’s activities in the Left Party (most recently in the 2004 state elections): at just over two per cent of the vote.

In addition to the outgoing candidate, however, the contenders for the office of Minister President played a role, if not the biggest role, in this election. Unlike, for example, in the state elections in March 2021 in Rhineland-Palatinate (Minas 2021) and Baden-Württemberg (Drewes 2021), it was not possible to identify any incumbency bonus for the incumbent Prime Minister Tobias Hans (CDU) running for election in Saarland in 2022 (Fahrenholz 2022). Hans, who was rather unknown until then, took over the Saarland State Chancellery from his predecessor Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer (CDU) in 2018. While the latter clearly won the fictitious direct election question for the office of Minister-President against her opponent Anke Rehlinger (SPD) with 52 to 38 per cent in the polls in the 2017 election, Hans lost this year in the fictitious direct election with 33 to 49 per cent against the very same Anke Rehlinger, who only built up a lead over the incumbent since November 2021 (Infratest Dimap 2022c). The Christian Democrat also lost out to the Social Democrat in polls on their ratings or popularity (ibid.; Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2022; Hirndorf and Roose 2022: 5). Hans’ poor poll ratings were based on several reasons. First, he was repeatedly accused of wavering in his management of the Coronavirus during the pandemic (Fahrenholz 2022). Moreover, he made a gaffe during the election campaign with a Twitter video in which he denounced high fuel prices and blamed the federal government while filming himself in front of a petrol station, differentiating between “low-income people” and “hard-working people.”

If we look at the role of leadership candidates in Table 1, we can see that, with regard to the CDU, just under a third of its voters chose the party because of Tobias Hans. The leadership candidates of the smaller parties remained rather pale and played only a minor role in the electoral decision for them. However, the leading role of the social democratic candidate Rehlinger is striking. With her personality, she developed a power of appeal that was recently only observed with Malu Dreyer in Rhineland-Palatinate (John 2022: 6; Minas 2021). 49 percent of SPD voters said they had voted for the party because of the candidate. No other party came close to such a high figure. During her tenure as minister, she also managed to build up a kind of incumbency bonus beyond the SPD’s supporters — a fact that the Social Democrats’ election campaign strategists took advantage of. As Minister of Economic Affairs, she was concerned by virtue of her office with issues such as jobs and the broader consequences of structural change in the country, the management of which was one of the main concerns of voters, as will be discussed in more detail in the next section. Her strongly personalised election campaign came to a head with a large-print election poster (Figure g) on which Rehlinger’s likeness was accompanied by the text “Our candidate for the office of Minister President.” While “Our Minister President” could be read large and clearly, one had to look much closer for the text in the middle — a coup of the party that visualises the role of the top candidate and her forced, suggested official bonus in the election campaign.

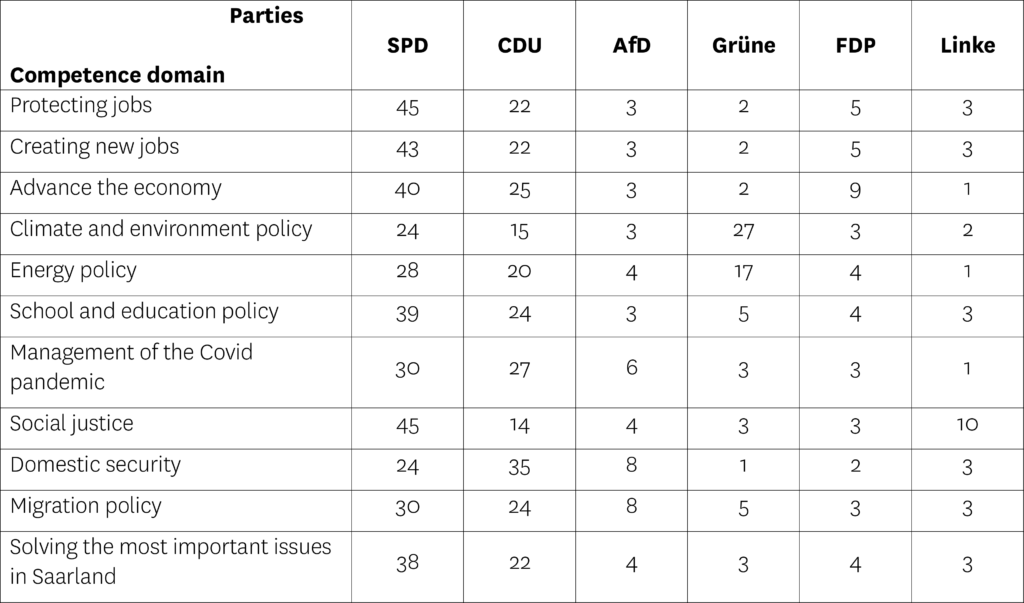

It’s the economy, stupid

Just under a month before the election, a quarter of the Saarlanders surveyed said that dealing with (the threat of) unemployment in the country was the most important problem at the moment. This was followed by dealing with the Corona pandemic (21 percent), mobility issues (18 percent), the economy and structural change in general (17 percent) and education (16 percent). Environmental protection and climate change ranked sixth with 10 percent (Infratest Dimap 2022a). The priority of the Saarlanders was therefore clearly on consequences (including jobs) and coping with economic structural change, which is not surprising in view of the dependence of the Saarland economy on its key industrial sectors. It is therefore interesting to look at the voters’ assessment of which party had the greatest competence in the individual policy areas (Table 2). It can be clearly stated that the SPD had a massive lead over its competitors in most of the decisive issues. The SPD is clearly ahead both in securing jobs and creating new ones, and in advancing the economy, as well as in the somewhat more abstract category of solving the most important problems of the Saarland. Not even in the area of Corona management does the SPD lose out to the CDU, which can be attributed in part to the fact that CDU top candidate Hans has been repeatedly criticised for his meandering course in Corona policy. In environmental and climate protection, the Greens rank first, while with regard to education policy, the SPD again scores best. Infratest Dimap (2022a) already painted a similar, if not yet so clear, picture one month before the election. The CDU not only lost out to the SPD in most categories, but also had to note in self-reflection that its competence attribution scores deteriorated significantly in retrospect to the last election in 2017 (Hirndorf and Roose 2022: 5f).

Outlook

If one interprets the results of this state election with a differentiated view of the electoral motives and contextual factors described above, it appears clearly that Saarlanders chose Social Democracy, but also primarily Anke Rehlinger herself, to solve the region’s problems. Despite the list voting system laid down in Saarland electoral law, a crucial personal factor can be identified which had a decisive influence on the voting motives of many Saarlanders. Another factor is that the issues that dominated were those that fell within Anke Rehlinger’s sphere of competence as former Minister of Economic Affairs.

Coalition issues only had to be speculated about before the election. Despite the recently elected traffic light coalition (SPD, Greens, FDP) in the federal government and the rather unloved coalition of CDU and SPD at the federal level, the Saarlanders clearly favoured the latter for the coming legislative period. In addition to the topical priorities, it became particularly clear here that this election clearly had a regional character, i.e. it hardly functioned as an indicator for federal politics or a predictor for other federal states. Due to the weakness of the smaller parties, which, with the exception of the AfD, all failed to enter the state parliament, the Social Democrats won an absolute majority in parliament and will henceforth govern the Saarland alone, while the CDU will have to reposition itself in the opposition and give itself a new profile. Although the AfD lost votes, it can so far rely on a small but solid electorate in Saarland that is willing to overlook internal party disputes. This is not the case for Bündnis90/Die Grünen. The Greens and the FDP continue to struggle to establish themselves in Saarland — which is partly due to the socio-demographics and the economic circumstances of the state. Whether the Left Party will manage to regain a foothold in Saarland politics without Oskar Lafontaine remains open or even doubtful.

References

Bittner, A. (2011). Platform or personality? The role of party leaders in elections. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American Voter. New York: Wiley.

Detterbeck, K. & Renzsch, W. (2008). Symmetrien und Asymmetrien im bundesstaatlichen Parteienwettbewerb. In: Jun, U., Haas, M., & Niedermayer, O. (eds.), Parteien und Parteiensysteme in den deutschen Ländern. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften: 39-55.

Drewes, O. (2021). Parliamentary Election in Baden-Württemberg, 14 March 2021. BLUE 1. Paris: Groupe d’études géopolitiques: 38-44.

Drewes, O. (2022). Parliamentary Election in Schleswig-Holstein, 7 May 2022. BLUE 3. Paris: Groupe d’études géopolitiques.

Fahrenholz, P. (2022, 28 March). SPD gewinnt Wahl im Saarland. Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Forschungsgruppe Wahlen (2022). Landtagswahl im Saarland. 27. März 2022. Online. Retrieved 13.5.22.

Hirndorf, D. & Roose, J. (2022). Landtagswahl im Saarland am 27. März 2022. In: Monitor. Wahl- und Sozialforschung. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. Online. Retrieved 13.5.22.

Infratest Dimap (2022a). SaarlandTREND Feburar 2022. Online. Retrieved 18.5.22.

Infratest Dimap (2022b). SaarlandTREND März 2022. Online. Retrieved 18.5.22.

Infratest Dimap (2022c). WahlREPORT Landtagswahl Saarland 2022. Berlin: infratest dimap.

John, S. (2022). Analye der Landtagswahl im Saarland 2022. böll.brief — Demokratie und Gesellschaft #28. Heinrich Böll Stiftung. Online. Retrieved 18.5.22.

Karvonen, L. (2010). The personalisation of politics. A study of parliamentary democracies. Colchester: ECPR Press.

Kirch, D. (2022a). Das Saarland steht vor einem Berg von Problemen. In: Kirch, D. (ed.), \wahlen. Die Landtagswahl 2022 im Saarland. wirklich\wahr. das junge magazin. Mainz: Medienebene e.V.: 7.

Kirch, D. (2022b, 7 April). Jetzt amtlich: Den Grünen fehlten 23 Stimmen. Saarbrücker Zeitung.

Kirch, D. (2022c, 18 March). Oskar Lafontaines Austritt bei der Linke. Saarbrücker Zeitung. Online. Retrieved 18.5.22.: Weiterer Paukenschlag zum Ende einer großen Ära. Online. Retrived 18.5.22.

Kollmann, M. (2020). §15 Saarland. In Kaiser, R. & Michl, F. (eds.), Landeswahlrecht. Wahlrecht und Wahlsystem der deutschen Länder. Baden-Baden: Nomos: 357-379.

Kruse, B. & Müller-Hansen, S. (2022). Wie die SPD die Wahl gewonnen hat. Süddeutsche Zeitung. Online. Retrieved 18.5.22.

Landeswahlleiterin (2022). Landtagswahl 2022. Online. Retrieved 18.5.22.

Loth, W. (2021). Land Saarland. In Andersen, U. et al., Handwörterbuch des politischen Systems der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Wiesbaden: Springer VS: 571-578.

Minas, M. (2021). Parliamentary Election in Rhineland-Palatinate, 14 March 2021. BLUE 1. Paris: Groupe d’études géopolitiques: 45-51.

Rahat, G. & Kenig, O. (2018). From party politics to personalized politics? Party change and political personalization in democracies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Saarbrücker Zeitung (2022). Das war’s: Linken-Politiker Oskar Lafontaine wird Privatmann. Saarbrücker Zeitung. Online. Retrieved 18.5.22.

Schoen, H. (2009). Wahlsoziologie. In Kaina, V. & Römmele, A. (eds.), Politische Soziologie. Ein Studienbuch. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag

SR.de (2022). Amtliches Endergebnis der Landtagswahl steht fest. SR. Online. Retrieved 18.5.22.

Winkler, J. (2018). Die saarländische Landtagswahl vom 26. März 2017: Bestätigung der CDU-geführten Großen Koalition. Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 49(1): 40-56.

Wurthmann, C. (2022). Parliamentary Election in North-Rhine Westphalia, 15 May 2022. BLUE 3. Paris: Groupe d’études géopolitiques.

Notes

- Whether this specific observation can also be found in other elections at the state level, whether a new trend and thus a new dynamic between the federal and state levels can be deduced in this respect, and what the possible reasons for this decoupling are, is to be examined in a separate study.

- Cf. Article 64 (1) of the Saarland‘s Constitution.

- For further specifics regarding voting laws, the electoral system and the distribution of seats in the Saarland see Kollmann (2020).

- In the previous elections Die Linke had obtained 12,8 % (2017), 16,1 % (2012) and 21,3 % (2009) of the votes.

- 2,3 % of the votes.

- 1,7 % of the votes.

- 1,4 % of the votes.

- 1,4 % of the votes.

- 1,0 % of the votes.

- Other parties or voter groups with a result of under 1 % of the vote: FAMILIE, Volt, Piraten (EFA), ÖDP (EFA), SGV, Gesundheitsforschung, Die Humanisten.

- From west to east: Merzig, Dillingen, Saarlouis, Völklingen, Saarbrücken, Neunkirchen, Homburg.

- In the municipality of Rehlingen-Siersburg in constituency 2 (Saarlouis), the SPD achieved an absolute majority of 50.5 per cent of the votes cast (Landeswahlleiterin 2022).

- One possible explanation for this is that the values given are to be considered relative to each other. On the one hand, a strong leadership candidate for the SPD increased the influence of the factor leadership candidate to the detriment of the factor party loyalty. On the other hand, a weak leading candidate for the CDU reduced the influence of the factor leadership candidate in favour of the factor party loyalty.

- Under the following link you will find an animated representation of voters’ migration. https://www.tagesschau.de/inland/waehlerwanderung-saarland-103.html. However, the following figures refer to the exit polls published by Infratest Dimap and reflect the balances of the voter flow accounts.

- This refers to both the incumbent state government (CDU/SPD) and the desired coalition of respondents in opinion polls before the election.

citer l'article

Marius Minas, Regional election in Saarland, 27 March 2022, Oct 2022,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue