Regional election in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, 22 October 2023

Günther Pallaver

Professor Emeritus of Political Science, Senior researcher at Eurac ResearchIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Günther Pallaver

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

The region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, located in Northeast Italy on the border with Austria, is divided into the two Autonomous Provinces of Trento and Bolzano. Both provinces elect their provincial parliaments on the same day. Together, the two provincial parliaments form the regional council, the region‘s legislative body. This is a clear indication of the two provinces‘ political and administrative dominance over the regional political system. Until the 2001 constitutional reform, the regional council was directly elected and then split into the two provincial parliaments.

Ethnic minorities live in both provinces: Trentino is home to a Ladin minority (3.5% of the overall population) and two small German minorities (0.5%), while in South Tyrol the German-speaking group dominates (69.4%), with the Ladin language group accounting for another 4.5% (see etnie 2014; Autonome Provinz Bozen – Südtirol 2023). This ethnic dimension has an impact on the provincial elections, as the Ladin minority is entitled to a seat in both provincial parliaments by law, regardless of the outcome of the election. This dimension is even more relevant in South Tyrol, where the provincial government must be composed with regard to the strength of the different language groups in the provincial parliament as provided by the autonomy statute (art. 50). For this reason, all candidates in South Tyrol must submit a declaration of language group affiliation before the election.

The elections for the next five-year term took place on October 22, 2023. Although the two provinces form a joint region, Bolzano (35 seats) and Trento (35 seats) use different electoral systems.

Electoral systems

The province of South Tyrol forms a single constituency. Voting is based on a proportional representation system without a threshold clause, with the option of casting up to four preferential votes. Voters residing abroad or temporarily out of the country have the option of voting by post. At least one third of male and female candidates must be represented on each list. The provincial government, including the provincial governor, is elected by the provincial parliament. Provincial governors can serve at most three consecutive terms (Provincial Act 2017).

The province of Trento also forms a single constituency. The electoral system has some differences with the one in use in South Tyrol. Namely, the provincial president is elected under a relative majority voting system with a variable majority premium, with provincial presidents serving at most two consecutive terms (Legge elettorale provinciale 2023). Each list must be associated with a candidate for the office of provincial president. Furthermore, the lists must be gender-balanced. Voters vote once for the candidate for the office of provincial president and one of the associated lists. They may cast two preferential votes, divided equally between men and women.

The electoral coalition led by the winning presidential candidate shall be allocated 17 seats (in addition to the president‘s seat) if it gathered less than 40% of the vote, and 20 seats if it gathered at least 40%. The coalition of the winning president may however not receive more than 23 seats. After the allocation of seats to the president’s list or coalition, the remaining seats are distributed proportionally among the other lists and coalitions. The seats are then distributed within each coalition (Camera dei Deputati 2023).

Context and results: Trentino

Throughout the First Republic, Trentino was a stronghold of the Democrazia Cristiana, Italy’s dominant Christian Democratic party. The only relevant regionalist party in Trentino is the Partito popolare Trentino Tirolese (Patt; Trentino Tyrolean People’s Party). Since the beginning of the Second Republic in 1994, however, Trentino had been governed by a center-left alliance until the victory of the center-right coalition in 2018 led to the election of Lega‘s Maurizio Fugatti as provincial president.

The 2018-2023 term was marked by the Covid pandemic and the ongoing debate surrounding the bear and wolf reintroduction program. A runner suffered deadly injuries from a bear attack in Spring 2023. Public protest ensued, driven both by opponents and supporters of bears and wolves. President Fugatti finding himself in the middle of the controversy, but had no direct powers to intervene.

The fragmentation of the party system has increased further with respect to the 2018 provincial elections. Of the 24 lists, 14 made it into the provincial parliament in 2023 (58.3%); in 2018, 22 lists ran, of which only 12 were successful (54.5%) (Provincia Autonoma di Trento 2018).

A fierce conflict between the Lega and Fratelli d`Italia (FdI) flared up before the elections over the choice of the lead candidate of the center-right coalition. As Trentino‘s president is elected directly by the people, the parties from the same political camp run in a coalition in order to remain competitive. The Lega insisted on running with President Fugatti as lead candidate, while FdI, on the other hand, pointed to the new majority after the 2022 general election. In the general election, FdI had obtained 25% of the votes in Trentino, while the Lega gathered only 10% (Brunazzo 2023a). The allies only reached a consensus shortly before the elections, with Lega’s Fugatti again leading the electoral coalition as the presidential candidate of the centre-right alliance.

The center-left camp chose the mayor of Rovereto, Francesco Valduga, as its lead candidate. While the decision was not as controversial as for the center-right, there still were considerable tensions between the political partners.

A total of seven candidates – six men and one woman – ran for the office of provincial president. Maurizio Fugatti was supported by eight lists, Francesco Valduga by seven. The third main lead candidate, Filippo Degasperi, was also the main challenger of the right-left duopoly. Having entered the state parliament in 2013 as a representative of the 5 Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle), Degasperi founded his own party Onda (Wave) in 2018, for which he also ran in 2023. Degasperi was supported by three parties. All other presidential candidates played only a marginal role.

| Presidential candidate | Number of lists | Percentage of votes | Number of votes | Preference votes for the candidate |

| Maurizio Fugatti | 8 lists | 51.82% | 129,758 | 7,375 |

| Francesco Valduga | 7 lists | 37.50% | 93,893 | 7,791 |

| Filippo Degasperi | 3 lists | 3.81% | 9,534 | 1,379 |

| Marco Rizzo | 1 list | 2.26% | 5,651 | 196 |

| Sergio Divina | 3 lists | 2.22% | 5,560 | 810 |

| Alex Marini | 1 list | 1.92% | 4,796 | 272 |

| Elena Dardo | 1 list | 0.48% | 1,205 | 85 |

Figure a · Candidates for provincial president

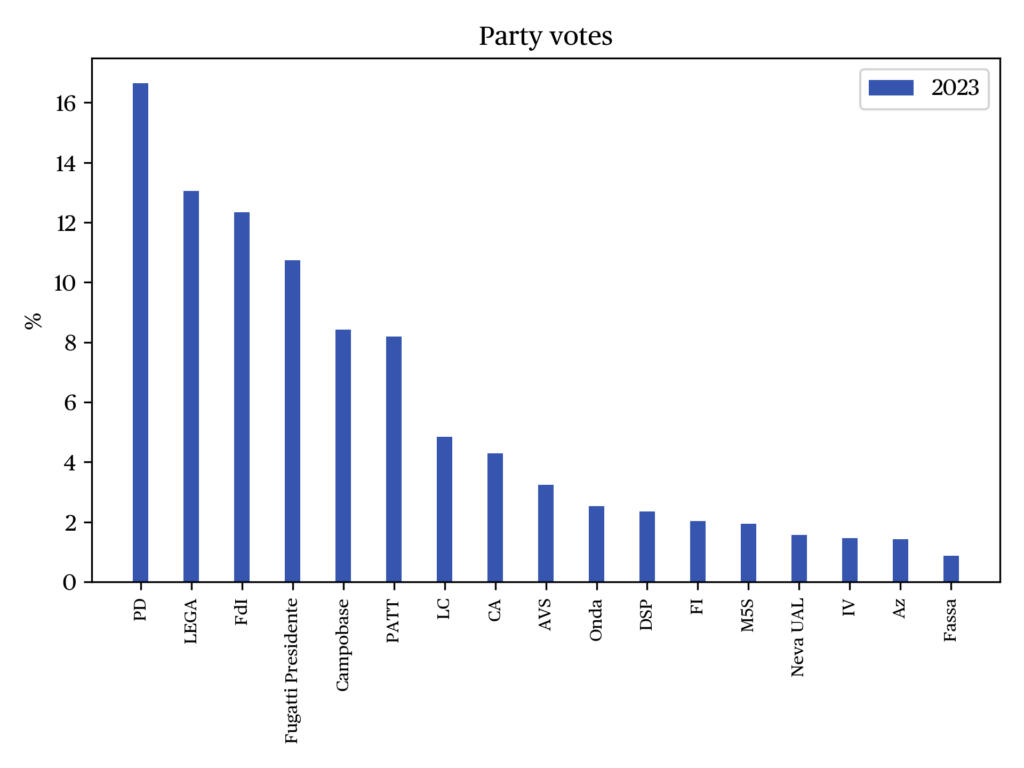

Maurizio Fugatti won the race with 51.8% (2018: 46.7%). In addition to his own Lega, he was supported by the FdI and Forza Italia. Francesco Valduga, a centrist, only received 37.5% (2018: 25.4%), which is 14 percentage points less than Fugatti received. Fugatti’s fears that the high number of candidates for the office of provincial president could favor his rivals did not materialize. Filippo Degasperi and former Lega party secretary and senator Sergio Divina also achieved only meagre electoral results.

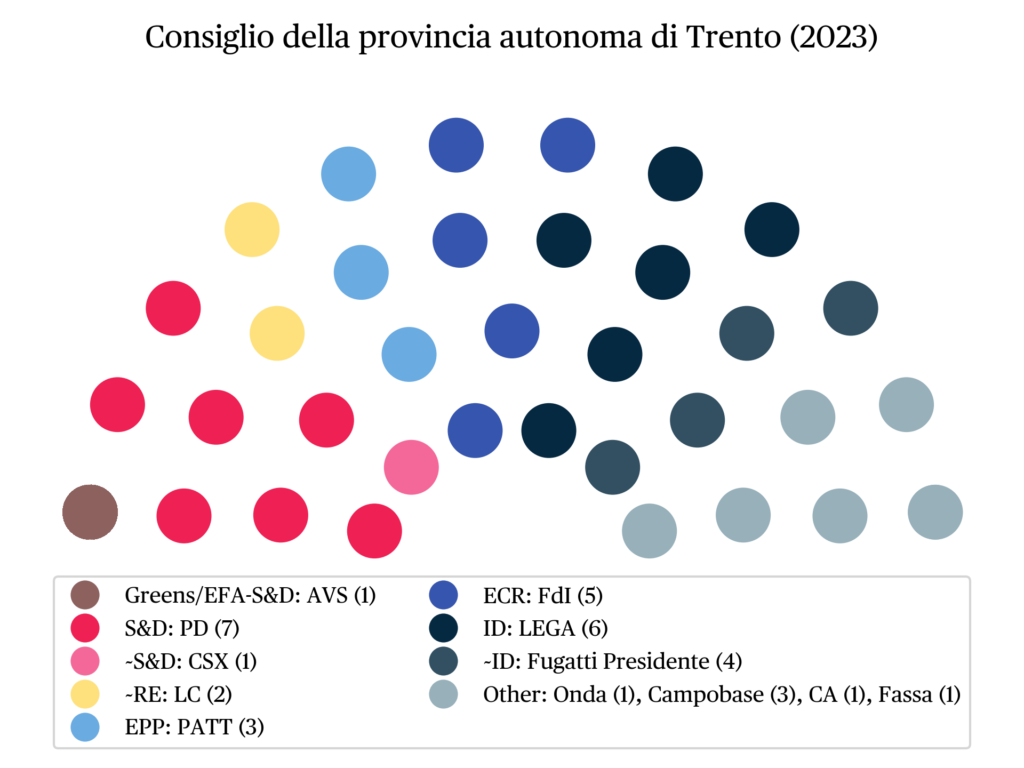

The center-right coalition won 21 seats thanks to the electoral premium, the center-left coalition 13, and Onda one.

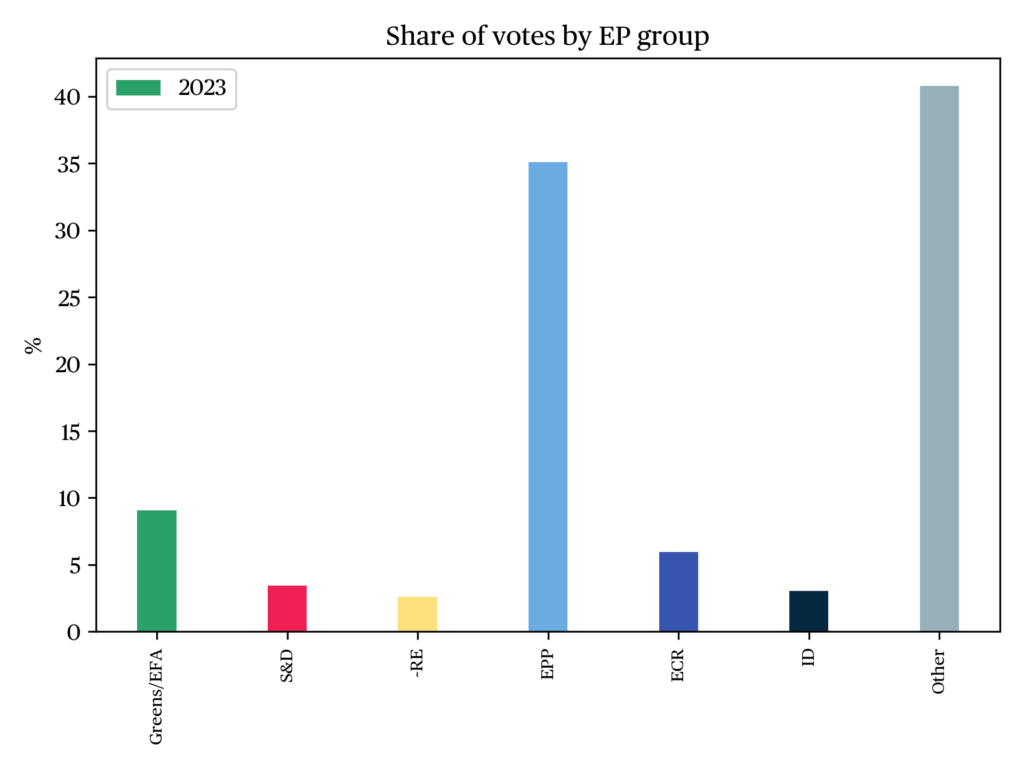

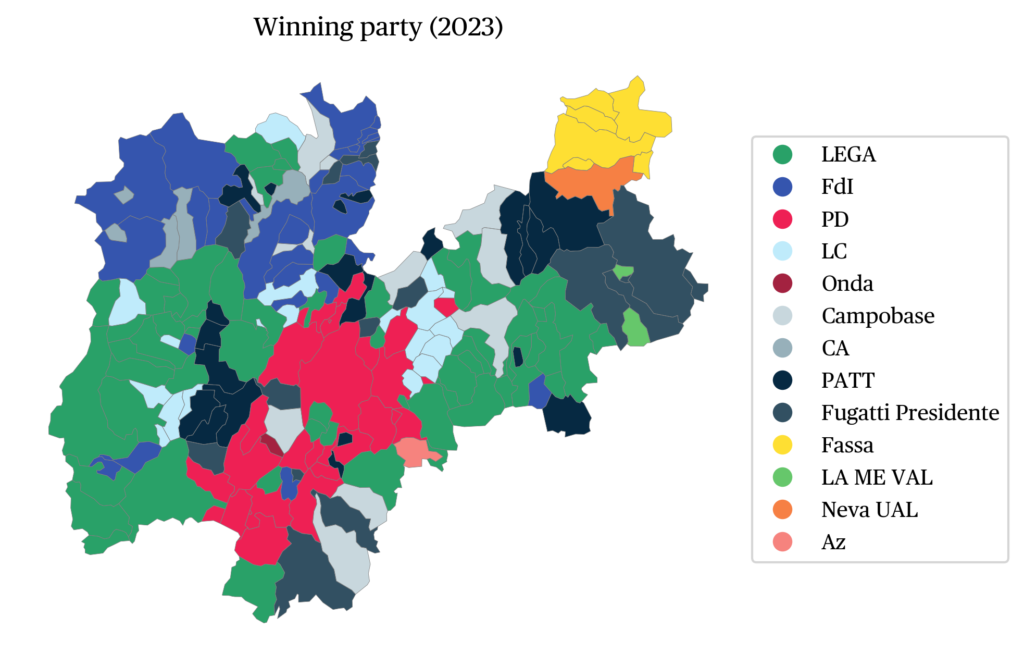

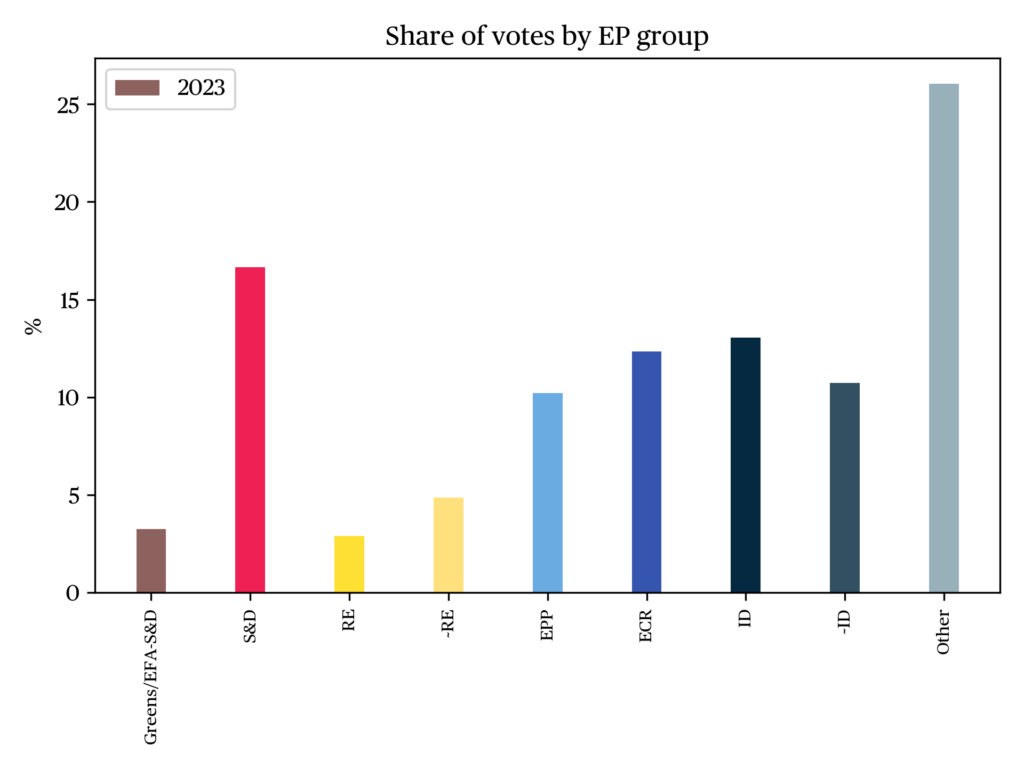

Among the parties, the Partito Democratico obtained the best result with 16.6% (2018: 13.9%), followed by the Lega (13.0%; 2018: 27.1%) and FdI (12.3%: 2018: 1.45%). The list Noi Trentini per Fugatti presidente (We Trentino for Fugatti President) also achieved 10.7%. It is worth noting that the Lega performed worse than in the 2018 regional elections, while FdI fell short of expectations and Forza Italia is no longer represented in parliament.

The political polarization that has emerged in the hard and controversial debate between the two major political camps (center-right and center-left) favored the two leading candidates, Fugatti and Valduga. In this debate between the left and the right, smaller parties outside the two major camps would hardly stand a chance.This, combined withthe nationalization of voting behavior, led to a strong demand for bipolarism. This was felt by the smaller national parties, especially Italia Viva, Azione, Movimento 5 Stelle and Forza Italia, none of which won a single mandate.

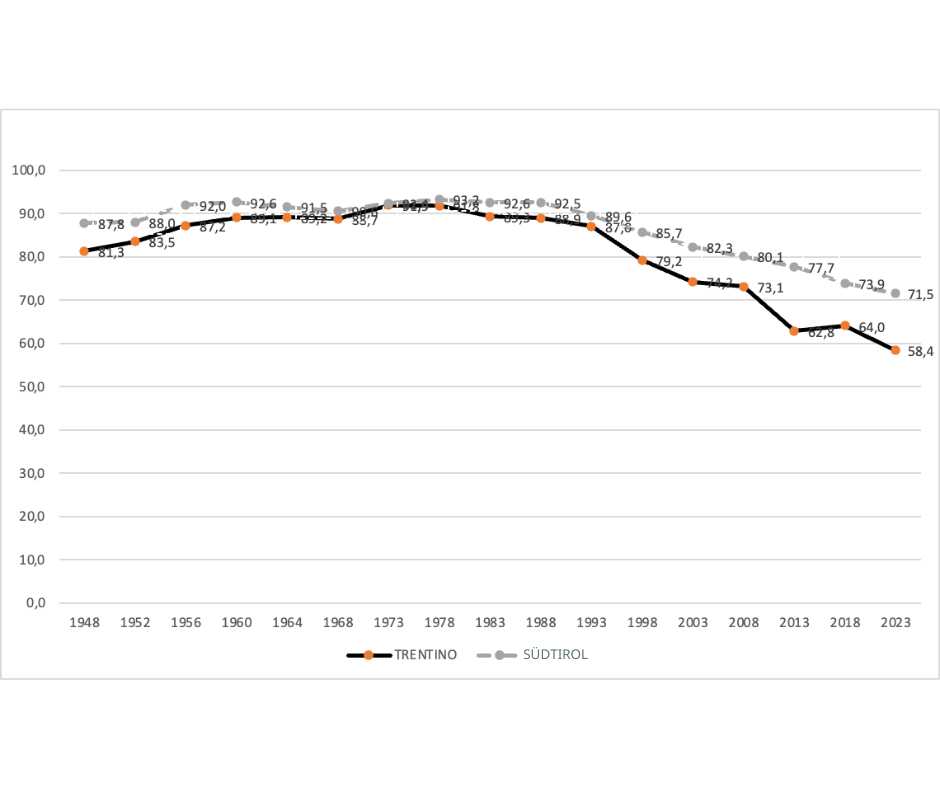

A cleavage also manifested between urban and rural areas. In the valleys, the center-right alliance received more votes, whereas the cities went to the center-left. The election also contradicted the commonly held assumption that polarization leads to higher turnout (Decker 2016). On election Sunday, only 58.4% of registered voters went to the polls, an all-time low since 1948. In 2018, 64.0% had turned out to vote. In Trentino too, the loss of trust in political parties appears to be increasing (Brunazzo 2023b)

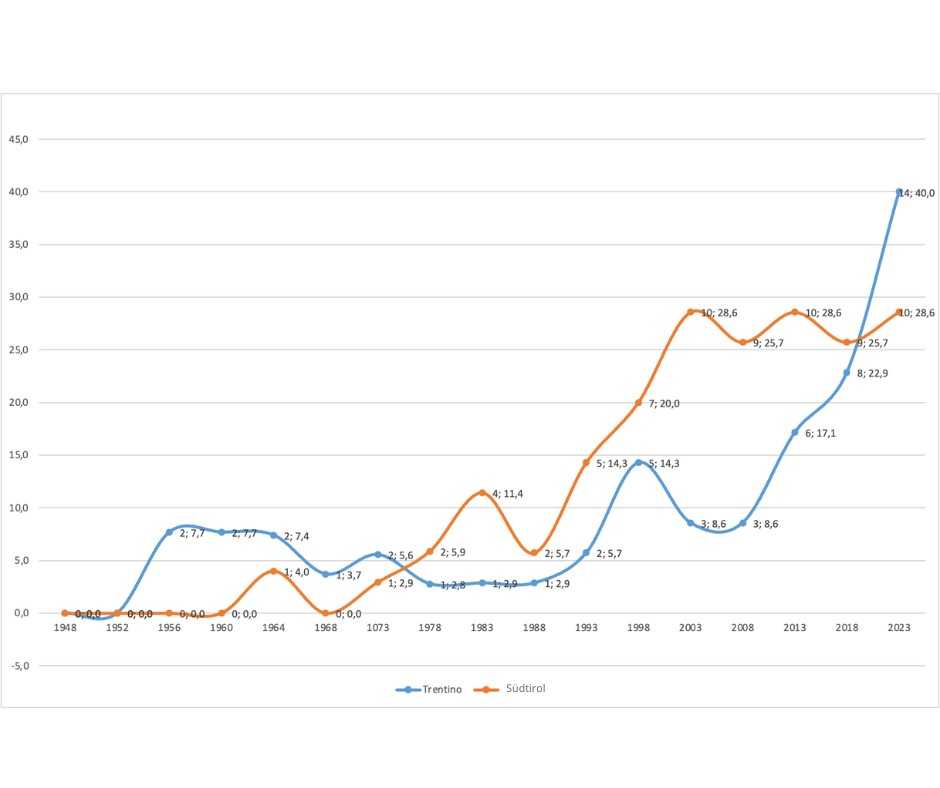

The increase in the number of women in the new provincial parliament is worth mentioning. 14 out of 35 members of parliament (40%) are female. In 2018, only nine women (25.7%) made it into the provincial parliament (see Figure b).

Figure b · Women in the provincial parliaments of Trentino and Alto-Adige/Südtirol 1948 – 2023

Context and results: South Tyrol

It was already clear months before the elections that the results of the vote in South Tyrol would bring surprises and set a new course. This was already evident in the structure of the political supply side. For the first time since 1993, 16 parties were competing for the 35 provincial parliamentary seats. For the first time too, there was a strong fragmentation not only among Italian-speaking parties, but also among German-speaking parties. Eight German parties faced off against seven Italian parties and one interethnic party. Between 2003 and 2018, there had only ever been between four and five German-speaking parties; the increase to eight indicates that the historical political homogeneity of the German and Ladin minorities is a thing of the past. The success rate was far higher for the German parties, of which seven eventually obtained seats in parliaments, than for the Italian parties, of which only four were successful.

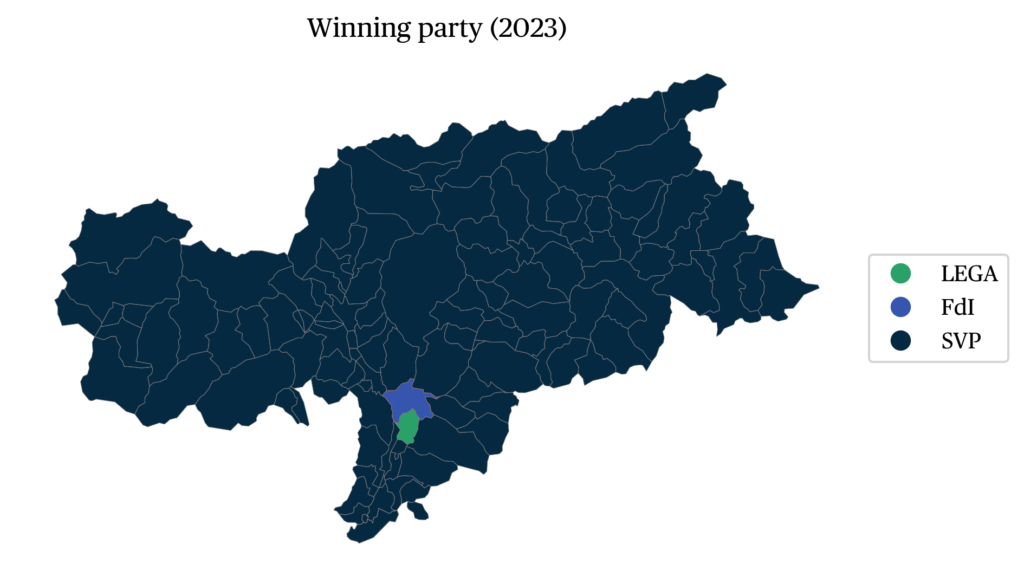

Despite the polarized election campaign, voter turnout decreased slightly. In 1998, it was 82.4%, whereas in 2023 it was 71.5%, 2.4% lower than five years earlier. Voter turnout should also be viewed from an ethnic perspective. In the German-speaking rural municipalities, voter turnout was over 80%. In the large, predominantly Italian cities, voter turnout was below 60%. The low voter turnout among the Italian population and the high turnout among the German population means that seats are being handed over from Italian-speaking parties to German-speaking parties. This “political withdrawal” of Italian speakers is partly due to their perception that they have only little influence on politics in the province, because – due to the ethnic proportionality system – they only ever represent a minority in the provincial government. This behavior has been noticeable since the beginning of the so-called Second Republic in the 1990s, albeit with some fluctuations.

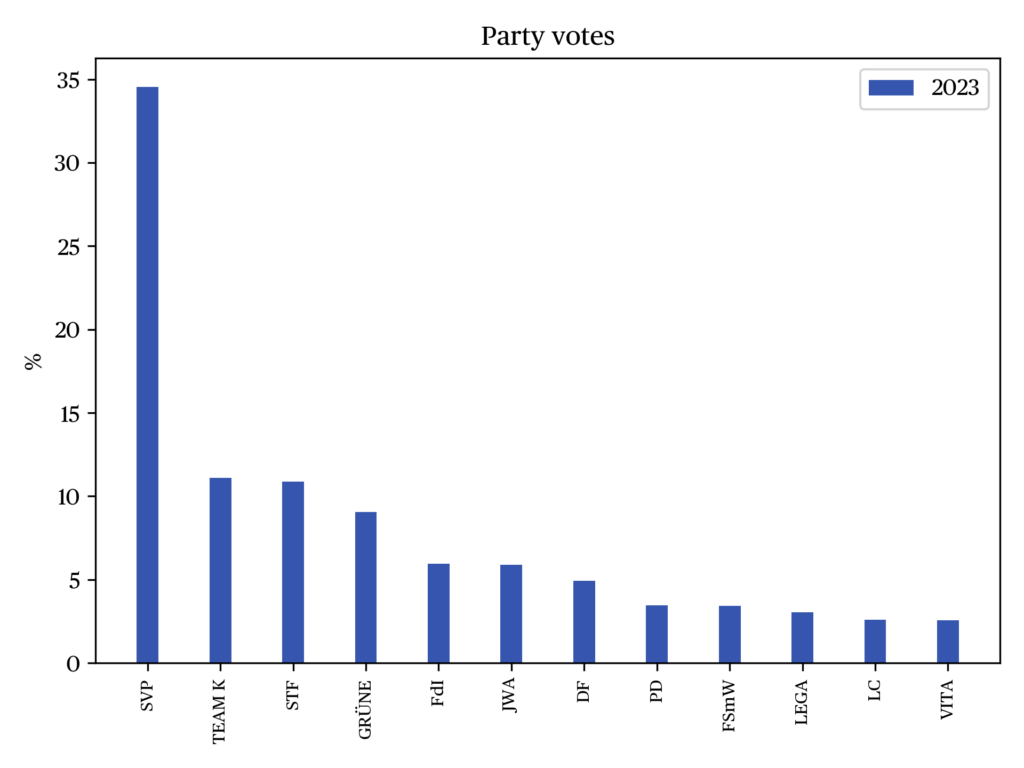

Figure c · Turnout in Trentino and Alto Adige/Südtirol 1948-2023

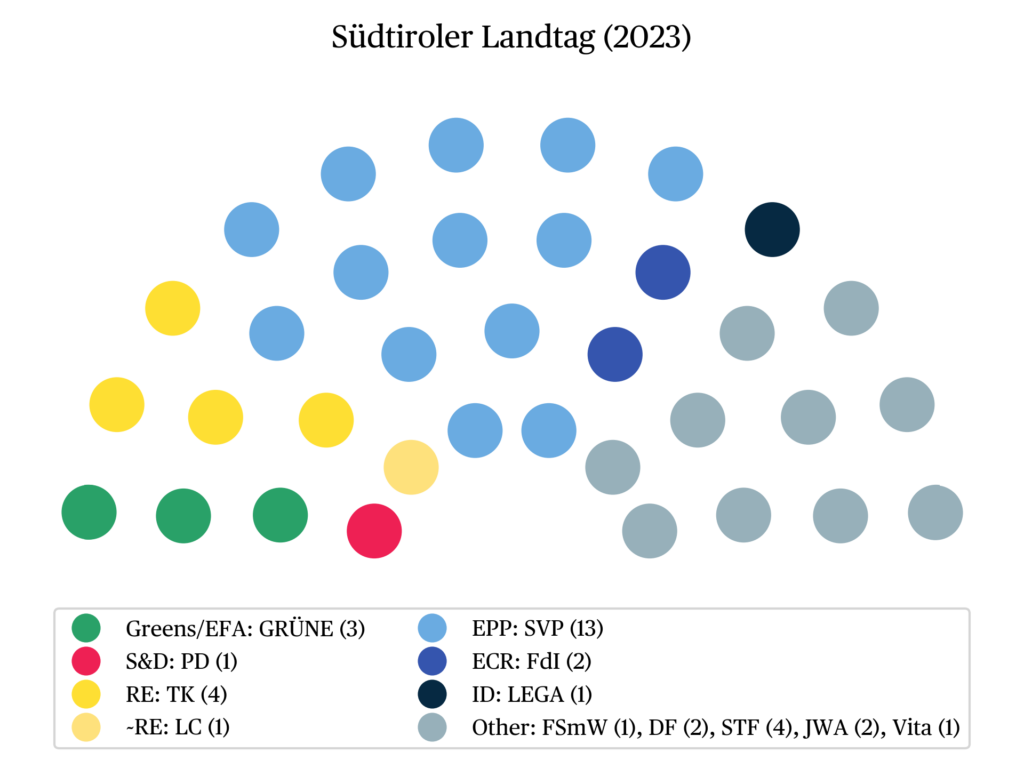

The once democratic-hegemonic South Tyrolean People’s Party (SVP) fell below the 40% mark for the first time in history, achieving only 34.5%. The SVP lost too seats and now holds 13 seats in the provincial legislature, including the only representative of the Ladin minority. This has led to a historic turning point, as the SVP can no longer claim to represent on its own the German and Ladin-speaking minority – indeed, it now only represents 45% of the minority. As a result, the SVP‘s capacity to represent the minority outside of the region is also weakened. Among the reasons for this defeat were constant internal conflicts between the social-liberal and conservative wings of the party, a series of scandals, the development of the SVP into a lobby party (mostly dominated by farmers, hoteliers and innkeepers), and the decision of the former party secretary after a conflict within the party to leave the party and form a new political movement. As a result, the SVP is less trusted to be able to solve the region‘s problems than it used to be in the past.

There were at least two further surprises in the German-speaking party system: The doubling of mandates from two to four for the secessionist party Südtiroler Freiheit (STF) and the entry into the provincial parliament of two openly anti-vaccination parties, JWA (Jürgen Wirth Anderlan) and Vita. JWA and STF also engaged in strong radical right-wing populist propaganda against “those on top” and foreigners.

Among Italian-speaking parties, it was to be expected that the Lega would lose votes, but not that it would save just one of the four seats it had held in the previous legislative period. Fratelli d`Italia, who only achieved two seats despite their national momentum, were expected to perform slightly better that they eventually did. After many failed attempts, this time an Italian center party, La Civica, made it into parliament.

| Lists | % | Seats |

| Südtiroler Volkspartei (SVP) | 34,5 | 13 |

| Team Köllensperger (TK) | 11,1 | 4 |

| Verdi/Grüne/Vërc (VGV) | 9,0 | 3 |

| Fratelli d’Italia (FdI) | 6,0 | 2 |

| JWA With Anderlan | 5,9 | 2 |

| Die Freiheitlichen (DF) | 4,9 | 2 |

| Partito Democratico (PD) | 3,5 | 1 |

| Für Südtirol mit Widmann | 3,4 | 1 |

| Lega | 3,0 | 1 |

| La Civica | 2,6 | 1 |

| Vita | 2,6 | 1 |

| Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S) | 0,7 | 0 |

| Enzian | 0,7 | 0 |

| Forza Italia (FI) | 0,6 | 0 |

| Centro Destra | 0,6 | 0 |

Figure d · Electoral results 2023 (% of votes und seats)

The election results show that the South Tyrolean electorate has shifted to the right. The political center gathered 54.2% of the votes and 20 mandates (SVP, Team K, Widmann, Vita, Civica), two less than in 2018. The center-left parties, PD and Greens, remained relatively stable at 12.5% and four mandates. The center-right and radical right-wing parties (Die Freiheitlichen, JWA, FdI, Lega, Südtiroler Freiheit) increased from 25.0% in the 2018 election to 30.7% in 2023, now holding eleven seats, two more than in 2018.

The new provincial government has also shifted to the right. It is now composed of the SVP, Lega, Fratelli d`Italia and the centrist party La Civica. The SVP justifies the formation of a coalition with far-right parties, from which the SVP had kept its distance in the past, by claiming that the government in Rome, consisting of FdI, Lega, Forza Italia and Noi Moderati, has agreed to an deepening of the autonomy status. This window of opportunity would hence justify their “pact with the devil”.

Lower voter turnout among Italian speakers has weakened the Italian-speaking parties. Only five Italian parties, down from eight in 2018, are represented in the new parliament, impacting the Italian presence in the political institutions.

Ten women were elected to parliament in the October elections, one more than in 2018. Only once before, in the 2003 elections, had eleven women been elected.

The data

Alto-Adige/South Tyrol

Trentino

Summary

The following trends can be identified with regard to the 2023 provincial elections in Trentino and South Tyrol:

- In the province of Bolzano-Alto Adige, elections are based on proportional representation, with the provincial governor being elected by the provincial parliament. Trentino also uses a proportional representation system, but with correctives. The Trentino elects its provincial president directly through a relative majority system, combined with a majority premium.

- In 2023, the fragmentation of the party landscape has experienced a further increase. For the first time since 1993, 16 parties were competing for 35 provincial parliamentary seats in South Tyrol. For the first time, there was strong fragmentation not only among Italian-speaking parties, but also among German-speaking parties. Twelve of the competing parties, or 75%, won seats in the provincial legislature. In Trentino, out of 24 parties running in the election, 14 made it into parliament (58.3%).

- Voter turnout is decreasing. At 71.5% (2018: 73.7%), turnout was higher in South Tyrol than in Trentino, where it was only 58.4% (2018: 64.0%). Due to the low voter turnout among the Italian-speaking population in South Tyrol, seats previously held by Italian-speaking parties have lost seats to German-speaking parties. Following the 2023 election, there will only be five Italian-speaking members of parliament in South Tyrol. This also reduces the representation of Italian speakers in the provincial government to a single representative if the government has fewer than eleven members.

- The South Tyrolean People’s Party fell below 40% for the first time since 1948. After only 45% of the minority cast a vote for the SVP, the party has lost its claim to represent the German and Ladin-speaking minority on its own. The SVP can therefore no longer be called a collective ethnic party, although it had actually already lost this status in the 2008 provincial elections (Atz/Pallaver 2009, 124-125). In Trentino, no party is currently nearly as relevant as the Democrazia Cristiana used to be. The strongest force is the Partito Democratico, followed by the Lega and Fratelli d`Italia.

- Compared to 2018, the number of female MPs has risen from 9 to 10 (28.6%) in South Tyrol and from 9 to 14 (40%) in Trentino. The difference between Bolzano and Trento also has to do with the electoral law. In South Tyrol, at least one third of male and female candidates must be represented on every list. In Trentino, the lists must have equal gender representation. The two preferential votes must be split between a man and a woman.

- Overall, the party system has changed in both Trentino and South Tyrol, becoming more fragmented and polarized in both regions. For the first time, a South Tyrolean government includes parties that have either rejected autonomy in the past or, at least, expressed major reservations.

References

Atz, H. & Pallaver, G. (2009). Der lange Abschied von der Sammelpartei. Die Landtagswahlen 2008 in Südtirol. In F. Karlhofer & G. Pallaver. (eds.), Politik in Tirol. Jahrbuch 2009 (pp. 95-127). Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen: StudienVerlag,.

Autonome Provinz Bozen – Südtirol (2023). Autonomie für drei Sprachgruppen. Online.

Brunazzo, M. (2022a, 27 September). Il politologo Brunazzo: In Trentino un’omologazione al resto di Italia. TGR Trento. Rai News. Online.

Brunazzo, M. (2023c). Elezioni provinciali 2023. Trento: Doculab.

Brunazzo, M. (2023b, 24 October). Dietro al voto in Trentino, “astensionismo e ritorno ai due poli”. TGR Trento. Rai News. Online.

Camera dei Deputati (2023). Le leggi elettorali delle Province autonome di Trento e di

Bolzano. Dossier n° 62 – Schede di lettura 12 ottobre 2023.

Civis.bz.it (2023). Landtagswahlen 2023. Wahl des Landtages der Autonomen Provinz Bozen–Südtirol. Endgültige Ergebnisse. Online.

Decker, F. (2016, 30 September). Sinkende Wahlbeteiligung. Interpretationen und mögliche Gegenmaßnahmen. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte.

Etnie (2014). Trentino: il nuovo censimento di ladini, cimbri e mocheni. Online.

Landesgesetz (2017). Landesgesetz vom 19. September 2017, Nr. 141. Bestimmungen über die Wahl des Landtages, des Landeshauptmannes und über die Zusammensetzung und Wahl der Landesregierung, Online.

Legge elettorale provinciale (2023). Legge provinciale 5 marzo 2003, n. 2. Online.

Pallaver, G. (2018). Südtirols Parteien. Analysen, Trends und Perspektiven. Bozen: Edition Raetia.

Provincia Autonoma di Trento (2018). Elezioni provinciali, 21 ottobre 2018. Online.

Provincia Autonoma di Trento (2023). Elezioni provinciali, 22 ottobre 2023. Online.

citer l'article

Günther Pallaver, Regional election in Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, 22 October 2023, Jun 2024,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue