Regional elections in Lower Austria, 29 January 2023

Daniela Ingruber

Researcher at Krems University of Further EducationIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Daniela Ingruber

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

The history of a provincial election

Lower Austria is not the most well-known part of Austria, but its largest Bundesland by area and its second most populous after the capital of Vienna. With the proclamation of the First Republic in 1918, Lower Austria became a federated entity within a greatly reduced Austrian state struggling with its identity. For Lower Austria, which had to share its state capital with the state of Vienna for many years, the quest for identity proved rather difficult. It was not until a referendum in 1986 that Lower Austria obtained its own state capital, St. Pölten. The high turnout in this referendum reflected a key aspect of the regional political culture: with 61.3 percent of all Lower Austrian citizens turning out to the polls – an unusually high percentage for a direct democracy tool –, the population’s desire for independence was quite clear. With its new regional capital and government district and the many urban, cultural and related investments that accompanied it, the region gained political self-confidence in the following years. Today, this self-confidence is more willingly displayed by the Lower Austrian authorities in domestic politics, where the region is keenly aware of the influence it can derive from its sizable electorate.

The close ties between Lower Austria and Vienna still exist today. In fact, some of the parties running in the 2023 Lower Austrian election also advertised in Vienna – after all, thousands of Lower Austrians commute to the federal capital every day.

On 29 January 2023, 1,288,838 inhabitants of Lower Austria over 16 years of age were eligible to vote in 20 constituencies (cf. Land NÖ 2023a). A total of 56 Landtag seats were at stake. Since young people, and therefore young voters, had been particularly affected by the Corona measures, the votes of the younger cohort were under particular scrutiny. Overall, the Lower Autrian vote benefitted from a high level of public attention, partly because it was the first of a series of three regional ballots that would also include Carinthia (5 March) and Salzburg (23 April). In this context, the January 29 election was considered a test.

Furthermore, it was expected that the Lower Austrian election would have an impact on federal politics. The vote was not only one the first one to take place since the end of the pandemic, but also came at the end of a long period in which corruption allegations and other political scandals had shaken Austrian politics, starting with the release of the so-called Ibiza video in 2019. For Chancellor Karl Nehammer, who himself comes from Lower Austria and started his political career there, this election was particularly important. A weakening of his party, the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), in the region would also impact its standing at the federal level.

Big losers and big winners

A total of 922,253 inhabitants of Lower Austria voted. This corresponds to a turnout of 71.56 per cent, which attests once again to the high degree of importance attached to this election by voters. Indeed in 2018 significantly fewer Lower Austrians – 66.56 per cent – took part in the state elections (cf. Land NÖ 2023a).

The polls did not predict a good result for Governor Johanna Mikl-Leitner, who has been in power since 2017. Her party, the ÖVP, which has ruled with an absolute majority almost continuously since 1945 apart from a ten-year period from 1993 to 2003 (Wiener Zeitung 2023), was expected to lose around ten percentage points, while the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) would grow by an equivalent or even higher percentage. The likelihood of the FPÖ increasing its vote share appeared particularly high in view of the party’s poor 2018 performance, which provided for a low baseline.

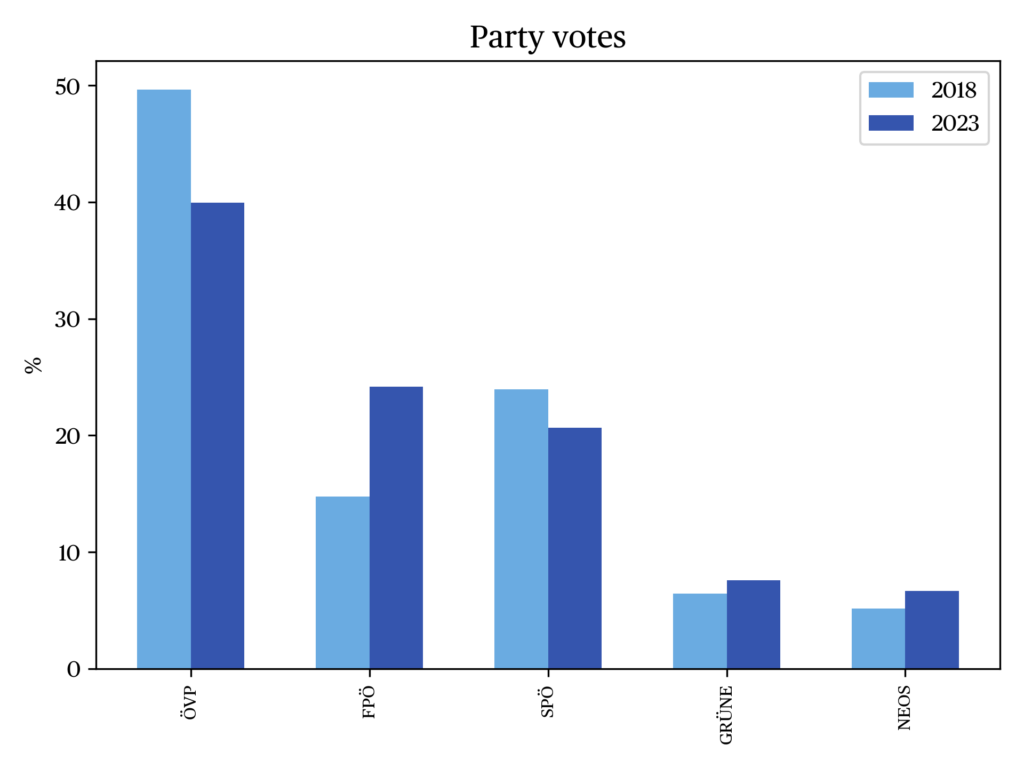

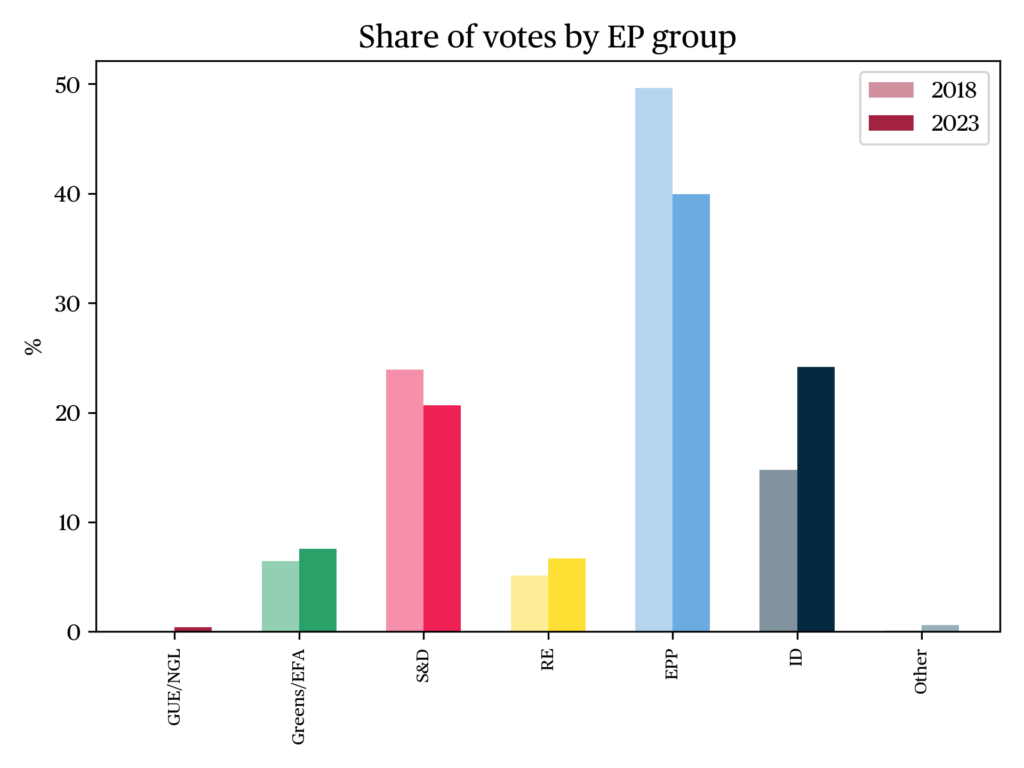

The ÖVP actually lost 9.70 percent (from 49.63 percent in 2018 down to 39.93 percent). The FPÖ increased their result from 14.76 per cent in 2018 up to 24.19 per cent, celebrating its best election result in Lower Austria to date. The Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ), previously in second place, also suffered losses, from 23.92 per cent (2018) to 20.66 per cent (Land NÖ 2023a). In a time of high inflation, war in the European neighbourhood and social problems, one could have expected a social democratic party to easily win votes; yet, the very opposite happened. Inner-party squabbles that had been going on for years threatened to escalate shortly before the Lower Austrian election; for months, the party appeared more occupied with itself than with the population’s concerns. On the day following the election, former SPÖ state party leader Franz Schnabl was urged to resign. He was replaced by Sven Hergovich, a young political leader and head of the Labour Market Service (AMS) of Lower Austria at the time. Hergovich stood for issues that the SPÖ had failed to address during the election campaign; yet, the quarrels within the party escalated further afterwards, and will continue to occupy the SPÖ for a long time.

Things were somewhat quieter around the Greens and the Neos, the other two parties that made it into parliament – unlike the Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ) and the anti-vax party “People-Freedom-Fundamental Rights” (Menschen-Freiheit-Grundrechte, MFG). While the Greens, with 7.5 per cent, did not achieve a record result (in 2013 they had gathered 8.06 per cent of the vote, in 2018 only 6.43 per cent), they however obtained enough votes to form a parliamentary group of their own. Forming a parliamentary group was one of the party’s major electoral goals, as this guarantees more rights in the Landtag as well as additional public funding (all figures: Land NÖ 2023a).

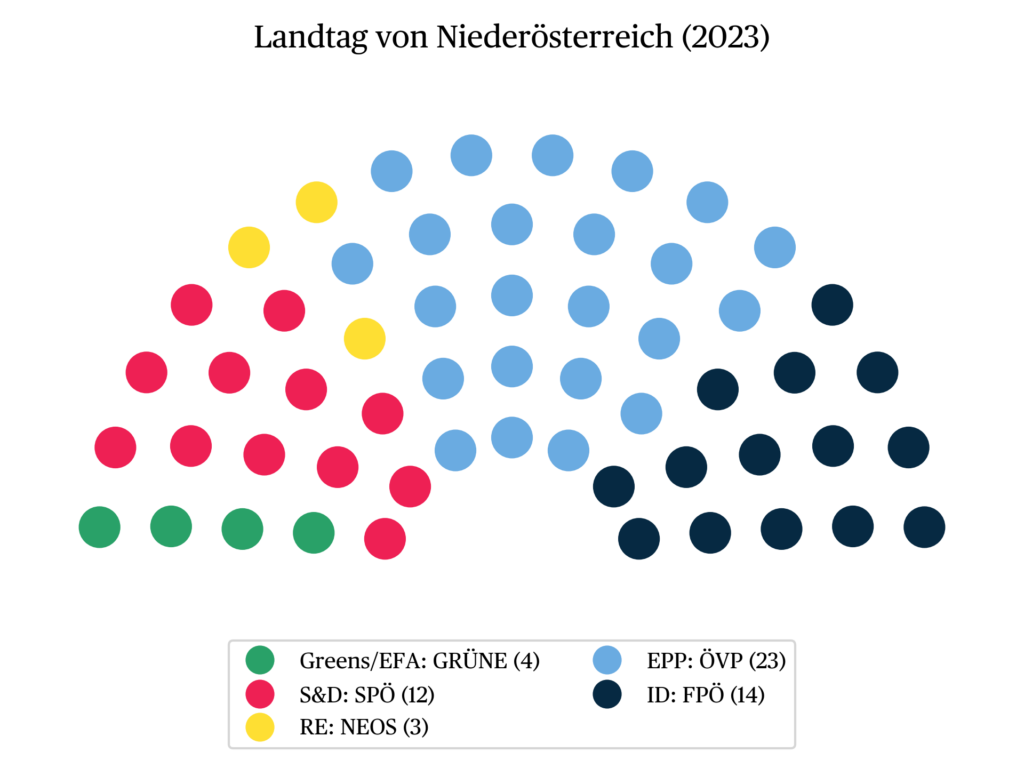

The Neos also increased their vote share, from 5.15 (2018) up to 6.67 per cent. They thus fell short of forming a parliamentary group by one seat. The final distribution of seats was as follows: ÖVP 23, FPÖ 14, SPÖ 12, Grüne 4 and Neos 3 mandates, with the three largest parties also automatically seating in the state government, which is elected using proportional representation (PR). This now heavily criticised PR system, which used to exist in many of the Bundesländer, means that every party above a certain vote threshold becomes part of the state government. This can lead to a party being part of the state government while also in (parliamentary) opposition, as is now the case for the SPÖ in Lower Austria (cf. Dolezal & Fallend 2023: 199; Perlot, Praprotnik, & Ingruber 2020: 195).

The pandemic as a key policy issue

Lower Austria provides an example of a state in which despite growing distrust in democratic institutions and participation, citizens have not withdrawn from the political scene altogether. The higher voter turnout can certainly be read as a challenge for the federal government and especially for the Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP), which was not able to attract these additional votes. During the election campaign it had already become clear that many citizens wanted to show once again that they did not agree with the state’s Covid policies.

In this context, journalist David Krutzler speaks of a “striking correlation between voting behaviour and the Covid measures” (Krutzler 2023). Indeed the FPÖ has been able to increase its vote share more in those municipalities where the vaccination rate against SARS-CoV-2 is particularly low. Some examples are the municipality of Gresten-Land, where “only one third of the population has a basic immunisation with three vaccine doses” (Krutzler 2023), as well as the village of Ertl, where both the losses of the ÖVP and the gains of the FPÖ amount to more than 20 percent. Such results are more than just symbolic. The ÖVP, as the most powerful party in the federal government, is responsible for the Covid measures, and Lower Austrian Governor Mikl-Leitner herself advocated for compulsory vaccination, even though she later dismissed this initial position as a mistake. Klaus Schneeberger, who was the ÖVP’s group leader in Lower Austria until the elections, told the Austrian Broadcasting Corporation (ORF): “We have already heard from our MPs that the vaccine issue in rural areas was, if you like, almost fatal for us” (quoted from Krutzler 2023).

Interestingly, the MFG, a party that started in 2020 with the intention of rallying anti-vax voters, did not achieve a good score. It only obtained 0.5 per cent of the votes, which can be explained by the fact that some of the candidates withdrew during the election campaign, and that the FPÖ addressed the same issue much more professionally and vocally (Krutzler 2023).

At this point, it must also be remembered that Austria’s politics has not only been in crisis since the pandemic, but that this process began in May 2019 at the latest, when the so-called Ibiza video was published. The subsequent scandal led to the end of the governing ÖVP-FPÖ coalition and then to the appointment of a transitional technocratic government, before a new National Council was elected in autumn 2020. But this was not yet the end of the scandals that shook Austrian politics. The outcome of the Lower Austrian parliamentary election was also influenced by the fact that in 2022, the young chancellor Sebastian Kurz, until then strongly supported by Governor Mikl-Leitner, had to resign to avoid being deposed. Since then, numerous social media chats have emerged that have furthered the suspicions of corruption within the ÖVP while leading to legal proceedings against some political actors. This also damaged the public image of the Landeshauptfrau (cf. Hagen & Marchart 2022; TT 2022).

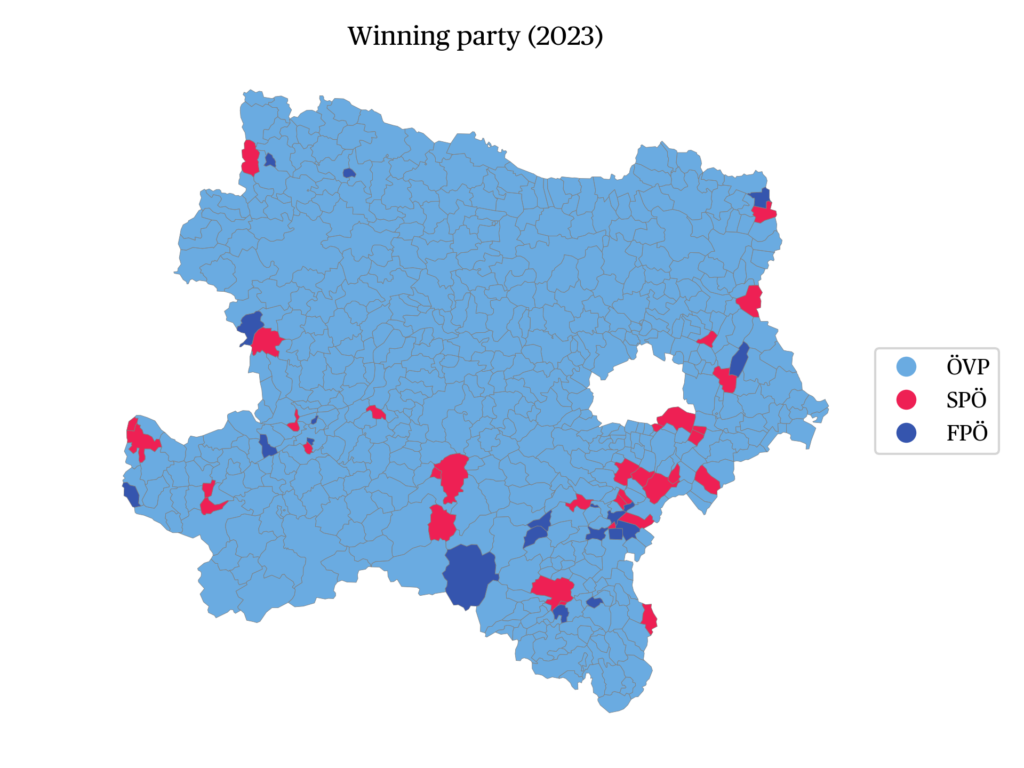

Of course, the ÖVP also celebrated a few local victories. E.g., in the municipality of Großhofen, the ÖVP received 81.8 percent of the votes. However, this plus of 17.8 percentage points corresponds to an absolute gain of only four votes. This illustrates the strong local dimension of the campaign, especially since many of the Lower Austrian municipalities are villages with few inhabitants. As a result of this spatial fragmentation, a party’s local victories do not necessarily impact its overall result in the Bundesland. However, the ÖVP only gained votes in seven municipalities, while the FPÖ only lost votes in two. In all other 566 municipalities except Großhofen, “the support for the People’s Party fell in comparison to 2018” (Rachbauer & Kohrs 2023).

When looking more closely at the determinants of the vote, the ÖVP was more likely to be voted for by women and citizens over 60, the FPÖ by men and young voters up to 29 years of age. The more citizens earn, the likelier they are to vote for the ÖVP, while the FPÖ performed better among the financially weaker – another indication the current societal divides may prove hard to bridge (Der Standard 2023). As mentioned above, the consequences of the pandemic have certainly impacted the election results, but the pandemic has also had the effect that many citizens no longer feel represented and understood by politicians. The party system as a whole has yet to find a strategy to regain trust and rebuild interest in political issues. Overall, the ÖVP and SPÖ are most impacted by voters’ distrust, and on election night, it became clear that they could not simply get back to “business as usual” during the next parliamentary term.

New coalition and first broken election promises

The election result caused the ÖVP to lose its absolute majority, thus forcing the party to to enter into coalition negotiations that it initially conducted with the SPÖ. While the media saw a black-red coalition as likely even after the failure of these negotiations, the ÖVP eventually ended up negotiating a coalition aggreement with the FPÖ. It thereby surprised observers as well as its own voters, particularly since both parties had confirmed on the evening of the election that they did not want to help each other to obtain executive power under any circumstances.

In the end, an unusual picture emerged: the hitherto rather successful Governor, who had been Austria’s Minister of the Interior from 2011 to 2016, decided to form a coalition with a party that she openly ruled out as a potential coalition partner during the election campaign – a party that, for its part, had also signaled a lack of interest in governing with her. Since Mikl-Leitern did not want to start her new term in government by breaking an election promise, the ballot papers for the election of the Governor (who is elected by the state parliament) and her deputies had to adapted so that invalid votes became possible (cf. Fellner 2023). In this way, Mikl-Leitner could be elected by her party colleagues plus one person. Her counterpart Udo Landbauer, head of the FPÖ parliamentary group, in fact received one more vote than Mikl-Leitner did (25 votes compared to 24) (Land NÖ 2023b).

The inauguration of the government on 23 March 2023 was rather unenthusiastic, and it almost seemed that more had to be endured than celebrated. The members of the regional governement were willing to show that they were only working together out of common sense and a feeling of responsibility towards the province of Lower Austria; this state of mind was regularly emphasised in media statements (cf. ORF 2023) with Mikl-Leitner rejecting all criticism of the new coalition agreement: “In five years’ time it will be the people of Lower Austria alone who will judge whether and how we have mastered our common duty – and no one else” (Mikl-Leitner in Land NÖ 2023b).

The distribution of portfolios was eagerly awaited, especially since the SPÖ had expressed their interest in the social affairs and labour ministries but, as an opposition party, had little bargaining power. Critical voices stressed that the FPÖ should under no circumstances be given the migration/asylum portfolio, especially since remarks by FPÖ party members on these issues had caused outrage in the country. It was obvious that the ÖVP would control the economy, education/science, agriculture and finance portfolios, among others. Eventually, the labour, sport, infrastructure, mobility and, most importantly, the asylum portfolio went to the FPÖ. The SPÖ obtained agendas such as social administration, construction law and health.

Potential consequences for federal politics

The new coalition will undoubtably attract a great deal of attention within the Austrian political scene in the next few years. An unpleasant situation initially arose for the federal government as the opposition suddenly held a one-seat majority in the Bundesrat due to the ÖVP’s losses, which could hinder the adoption of legislation in the longer term. However, the government regain its majority following the Carinthian state elections (Parliament 2023).

Since the January 29 election, the FPÖ has benefited from very positive electoral trends; in the same time, the pressure on the party to deliver on its campaign promises increased. Since it could well be that the next National Council elections will take place before the regular election date in autumn 2024, any political mistakes made in the course of the next months may incur a significant electoral cost. In this respect, the FPÖ may not be in the most favorable situation. However, if the coalition succeeds in delivering on its first election promises fast, the right-wing populist party, which according to the latest polls could obtain very good results in the next National Council elections, could experience another major success. The first weeks of the coalition have provided more arguments in favour of this scenario: although no major social or economic decisions were made, the most prominent election promises of the FPÖ were implemented, thus giving the impression, at least in the media, that the junior partner was outshining the state governor’s party.

For Europe, this state government is a kind of test, because the EU-critical FPÖ will also take care of the European agendas. The most interesting aspect of this coalition, however, is the transformation of two parties that have gone from publicly celebrating their dislike of each other to a signing agreement that they had hitherto ruled out, and are now framing as the only feasible and responsible option on the table. How this coalition works out in practice remains to be seen. The aim of maintaining or gaining power is openly visible and contradicts numerous pre-electoral statements by political actors. As for now, it is not known whether the agreement will cost votes in a future election. What is very clear, however, is that no strong supporter of the European idea will govern Lower Austria in the next few years.

The Data

References

Der Standard (2023, 29 January): Landtagswahl in Niederösterreich: FPÖ bei unter 60-Jährigen stärkste Partei. Der Standard.

Dolezal, M. & Fallend, F. (2023): Die Länder: Landtage und Landesregierungen. In Praprotnik, Katrin/Perlot, Flooh (eds.), Das Politische System Österreichs. Basiswissen und Forschungseinblicke. Vienna/Cologne: Böhlau Verlag, p. 185–214.

Fellner, S. (2023, 15 March). Wahl im Landtag: Neuer Landeshauptfrau-Stimmzettel in Niederösterreich erlaubt ungültiges Wählen. Der Standard.

Hagen, L. et Marchart, M. (2023, 8 February). Mikl-Leitner erklärt „Gsindl“-Chat über SPÖ mit Streit in Flüchtlingskrise. Der Standard.

Krutzler, D. (2023, 31 January). FPÖ staubt in impfskeptischen Gemeinden in Niederösterreich ab. Der Standard.

Land de Basse-Autriche (2023a). Landtagswahl 2023. Endgültige Ergebnisse. En ligne.

Land de Basse-Autriche (2023b). Pressemitteilung: Angelobung der Mitglieder der NÖ Landesregierung auf die Bundesverfassung. En ligne.

ORF – Österreichischer Rundfunk (2023, 23 March). Mikl-Leitner mit 24 Stimmen gewählt. ORF.

Parlament Österreich (2023, 30 January). Niederösterreich-Wahl: Koalition büßt Mehrheit im Bundesrat ein. Parlamentskorrespondenz 80.

Parlament Österreich (2023, 14 April): Personalrochaden im Bundesrat: 16 Mandatar:innen angelobt. Parlamentskorrespondenz 403.

Perlot, F., Praprotnik, K., & Ingruber, D. (2020). Wie LandespolitikerInnen über den Föderalismus denken. Ergebnisse einer Umfrage. In Hermann, A. T., Ingruber, D., Perlot, F., Praprotnik, K., & Hainzl, C., regional. national. föderal. Zur Beziehung politischer Ebenen in Österreich. Vienna: Facultas AG, 191–202.

Rachbauer, S. & Kohrs, R. (2023, 1 February). Sechs Details zur Niederösterreich-Wahl: FPÖ holte zwölf Gemeinden von ÖVP. Der Standard.

TT – Tiroler Tageszeitung/APA (2022, 8 February). Neue ÖVP-Chats: Mikl-Leitner entschuldigt sich, SPÖ fordert Reaktion. Tiroler Tageszeitung.

Wiener Zeitung (2023, 29 January). Der ÖVP drohen Rekorde. Wiener Zeitung.

citer l'article

Daniela Ingruber, Regional elections in Lower Austria, 29 January 2023, Nov 2023,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue