Danish defense opt-out referendum, 1 June 2022

Issue

Issue #3Auteurs

Rasmus Brun Pedersen , Derek Beach , Roman Senninger , Jannik Fenger

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

Introduction

In a historic referendum on June 1st 2022, the Danish citizens voted in favor of removing the country’s defense opt-out. As a result, Denmark joins all of the other member states in participating in EU defense policy cooperation. The referendum was announced by the Danish government on 6 March 2022 following a broad multi-party defense agreement that came in the wake of the shake-up of Europe’s security architecture after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which also triggered the applications by Sweden and Finland to join NATO.

The Defense opt-out was one of the four Danish opt-outs from further European integration that followed in the wake of the Danish rejection of the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992. As the scope and importance of several of the Danish opt-outs has increased over the years following the deepening of European cooperation in areas covered by them, Denmark has held three referendums since 2000 that were aimed at abandoning or modifying its opt-outs: 1) joining the third phase of EMU in 2000, 2) revising the Justice and Home Affairs (JHA) opt-out to a British-style opt-in in 2015, and 3) joining the EU defense cooperation in 2022. In the EMU referendum, 53.2% of the voters voted No, and 53.1% of the voters rejected revision of the JHA opt-out in 2015. Based on past behavior, it might have been expected that the Danes would again vote no to removing an opt-out.

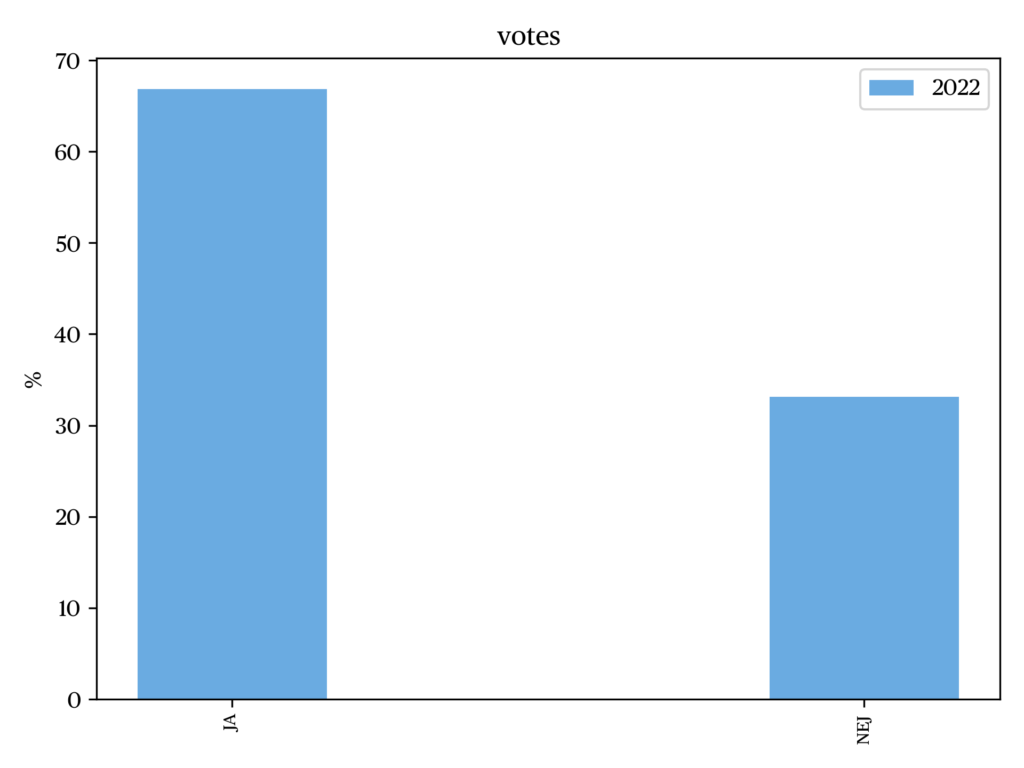

While high levels of Euroscepticism can explain the Danish no in 1992, Danish attitudes had softened by the mid-1990s to being broadly supportive of the European cooperation but without wanting more. In the No votes in 2000 and 2015, voters expressed their opposition to transferring more competences to the EU level (Hobolt 2009; Beach 2021). In contrast, despite having relatively unchanged attitudes towards transferring more sovereignty to the EU, Danes voted overwhelmingly in June 2022 by 66.9% to 33.1% in favor of removing the defense opt-out. What can explain this change in voter behavior?

The Danish defense opt-out

In the referendum on the 2 June 1992, a slim majority (50,7%) of Danish voters rejected the Treaty of Maastricht. To avoid blocking the treaty being adopted, a compromise was found between a majority of Danish parties which stated that Denmark would stay outside of four areas of potential future EU cooperation: JHA, the third phase of EMU (the euro),

1

EU citizenship and EU defense cooperation. As with the other opt-out areas, in 1992 there were not common defense policies in the EU. But Danish voters were concerned in the referendum that a supranational framework might develop in defense policies that could even lead to Danish troops coming under the EU flag (an ‘EU army’). Therefore, the Danish opt-out was formulated based on the need to reassure skeptical voters that Denmark would not be forced to join unwanted areas of cooperation. When the first intergovernmental EU defense policies were adopted in the Treaty of Amsterdam in 1998, Denmark received a protocol allowing it to remain outside of defense cooperation (Nissen 2022).

The Danish opt out is unique, as no other country has an opt-out in the defense area (Butler 2020). From a judicial perspective, the opt-out allowed Denmark to stay outside of several areas of Treaty cooperation (Art. 26 (1); Art. 42-46 EU) that have “military implications.” This implies that Denmark is outside the parts of the European cooperation that are based on these articles because they involve EU military cooperation. For instance, this means that Denmark cannot participate in EU missions with a military component, but Denmark can participate in civilian missions even though they take their point of departure in article 43 (DIIS 2019). The opt-out has been designed in a manner in which Denmark formally does not take part in the cooperation, in exchange for not blocking developments for others. Since EU defense cooperation is intergovernmental (participation is voluntary and decisions are taken with unanimity), removing the opt-out would have no sovereignty implications legally. Because EU common defense policies are intergovernmental, there were for many years only low intensity cooperation in the issue area. This changed after 2014 and the Russian invasion of Crimea, which sparked a rapid development in EU defense policies. This meant that Denmark was increasingly marginalized. In the period from 1993-2022 the Danish opt-out was activated 235 times (Think Tank Europe 2022), understood as instances where Denmark did not participate in EU military cooperation decisions related to articles 42-46 EU. In concrete terms, Denmark was excluded from the working of the European Defense Agency (EDA), Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), military operations and missions under the CFSP, and negotiations and discussions related to the broader developments in the defense area in the EU (DIIS 2019).

Campaign dynamics

In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, a new defense agreement was adopted by a large majority in parliament. There is in total 179 seats in the Danish Folketing. 175 are elected in Denmark, while the Faroe Islands and Greenland each has 2 seats in the Folketing. The parties behind the defense agreement were the Social Democrats (49), the Liberals (39), The Conservative People’s Party (13), the Socialist People’s party (15), and the Social Liberal Party (14). The agreement both included a decision to increase defense spending, end the dependency of Russians oil and gas, but it also included an ambition to abolish the Danish defense opt-out. Liberal Alliance (3), the Christian Democrats (1) and the Independent Greens (3) also endorsed the agreement. The Danish Peoples Party (16), the New Right party (4) and the Red-Green Alliance (13) opposed the abolition of the opt-out and recommended a no-vote.

The campaign was dominated by the narrative from the Yes campaign that Denmark needed to stand together with the rest of Europe. Implicit in this argument was that it was a response to an increasingly aggressive and assertive Russia. However, most Yes elites did not suggest that the EU’s common defense policy could be actually used to stop current Russian aggression. Instead, it was argued that the EU could play an important complementary security role regionally (e.g. in the Balkans) that could free NATO to concentrate on Russia. The main argument put forward by the No-campaign was that the abolishment of the opt-out could lead to a slippery slope of stronger defense cooperation that might become supranational in the future which could result in Denmark losing the ability to control the deployment of Danish troops. One particular concern was whether Denmark might be forced to take part in common EU actions in Africa.

Observers and analysts noted that the campaign was rather underwhelming when compared to the level of debate in national elections and (most) previous EU referendums in Denmark. Given the complexity of the topic and the uncertainty about where EU common defense cooperation was going, the campaign was also characterized by the frequent appearance of experts in the press and in tv debates who were asked to qualify political arguments made by the Yes and No side.

Public opinion polls published throughout the campaign showed a relatively comfortable lead for the Yes-campaign. In the 2015 referendum, there had also been an early lead for the Yes side that had slowly eroded during the course of the campaign. In 2022, while the gap between the ‘Yes’ and ‘No’ supporters narrowed somewhat by the beginning of May 2022, there were no polls that showed a lead for the No vote. As with previous opt-out referendums, there were a substantial number of voters (roughly 35-40% of the electorate) who were undecided until very late in the campaign. As with the 2015 referendum, undecided voters played a major role for the result. But whereas the undecided voters in 2015 broke towards voting no, the opposite occurred in 2022.

Election results — a strong country-wide ‘yes’

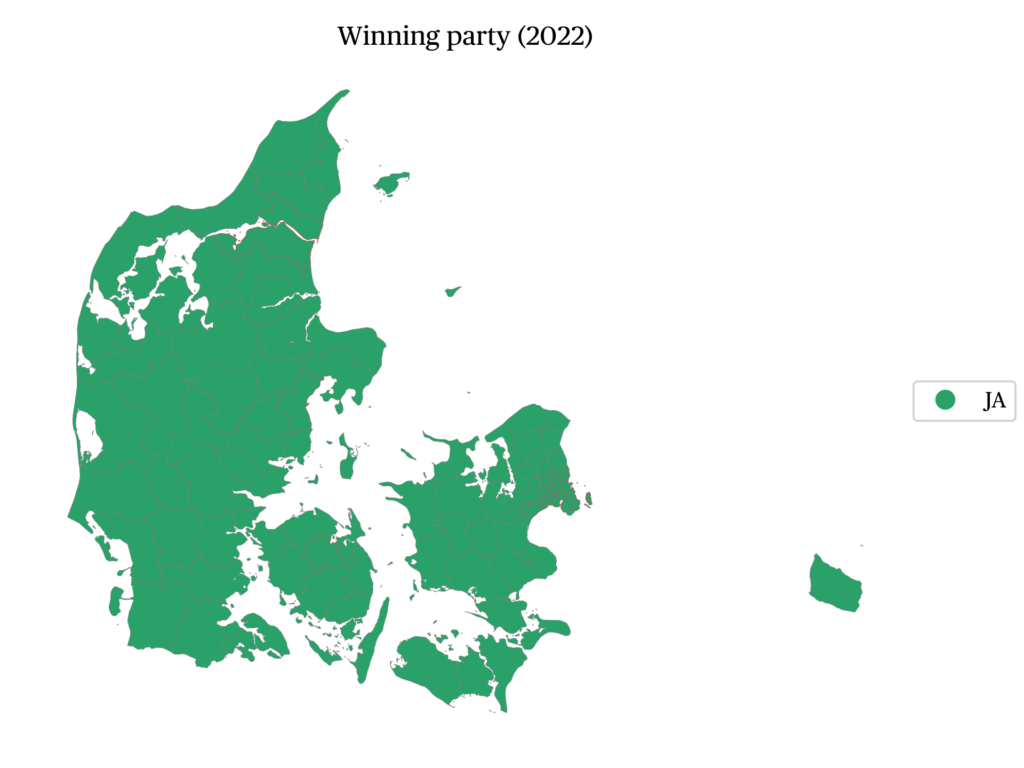

While the Yes majority was not surprising given the consistent polling, what was surprising was the size of the Yes vote. In total, 66,87% voted ‘Yes’ and 33,13% votes ‘No.’, with 65.77% of the electorate participating in the referendum. This was the second-lowest turnout ever observed in an election or referendum in Denmark. Observers lamented the relatively low turnout, but when compared to other referendums across the EU, the turnout is still relatively high (Beach, 2018). The clear victory of the yes campaign is also reflected in the results across the country. Overall, there was not a single municipality in which the voters preferred a ‘No.’ In fact, only a few polling station areas in the country reported a majority for the No-campaign.

What can explain the yes vote?

Data from a panel survey that we conducted in which a representative sample of the Danish voting population was interviewed at the beginning of the campaign in April and re-interviewed immediately after the referendum (N=1249) allow us to gain insights about dynamic changes in public opinion throughout the campaign, and assess the motivations for voting yes or no (Beach et al. 2022).

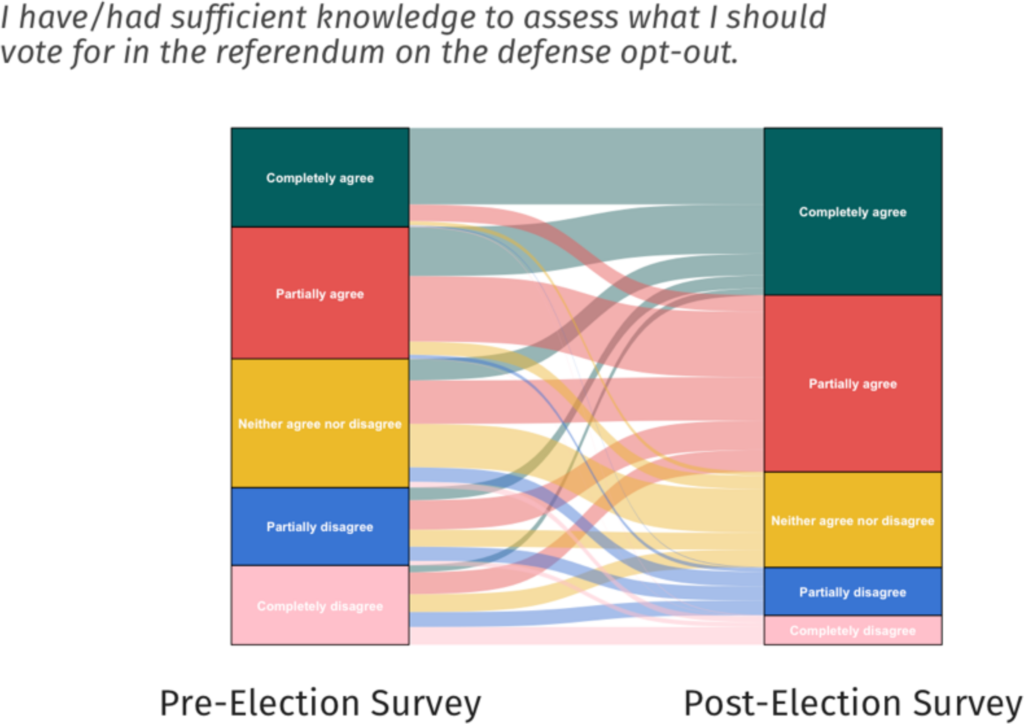

First, as with previous opt-out referendums (Hobolt 2009; Beach 2021; Beach and Finke 2021), there is evidence that most voters believed to have sufficient information to make a qualified choice, and that they thought the referendum was important enough to vote based on the issue and not second-order factors such the popularity of the incumbent government. In April 2022, 45% of the respondents said they had sufficient information to make an informed choice, whereas by the vote, 67% believed they had this information (see Figure a). Additionally, more voters were able to identify misleading arguments from the No-camp as such by the end of the campaign than at the start.

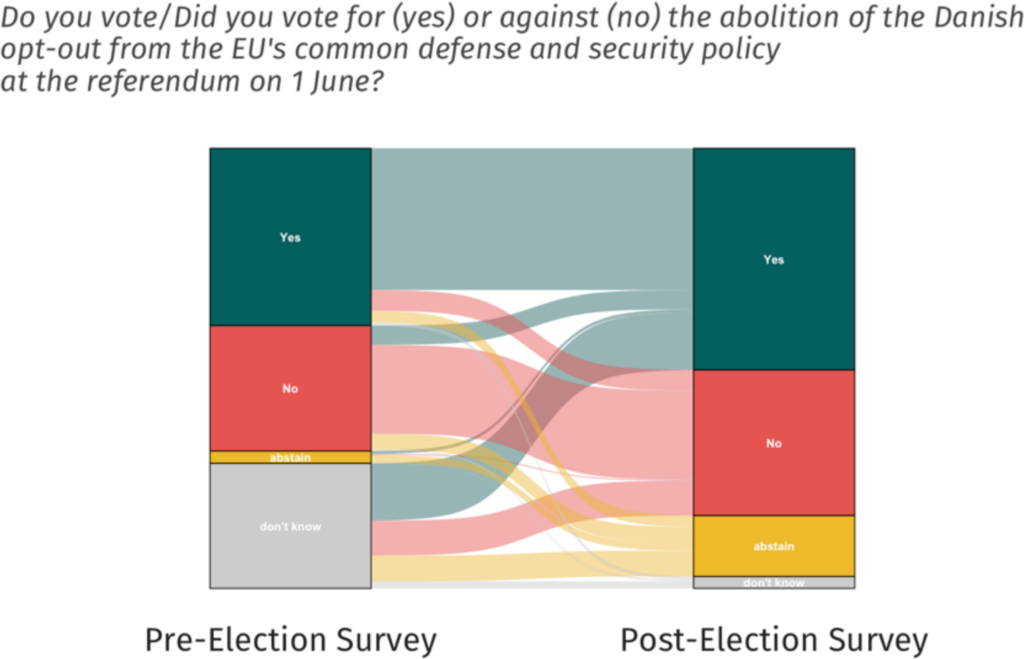

As in the 2015 JHA opt-out referendum (Beach and Finke 2021), most voters ended up voting as they stated they intended at the start of the campaign. However, a majority of undecided voters broke towards voting no in the final weeks of the campaign (Beach 2021). In 2022 a larger share of undecided voters moved to the Yes-camp. In total, 46% of the undecided voters ended up voting ‘Yes’ and 28% voted ‘No’ (see Figure b).

What can explain the movement towards voting yes?

When we compare EU attitudes of voters in 2015 and 2022 in our surveys, there is little evidence that Danes have become more supportive of more EU integration in general (Beach 2016; Beach et al. 2022). Indeed, a majority of voters in both 2015 and 2022 stated that they did not desire ‘more EU.’

When voters were asked about why they voted yes or no in our 2022 survey, the strongest arguments for voting yes related to solidarity with the ‘common foreign and security policies of our European neighbors’ (39% very important, 53% important), and increasing Danish influence in the EU (30% very important, 50.5% important). In contrast, fewer yes voters were motivated by the desire to take part in EU military missions (9.5% very important, 42.6% important). “No”-voters were motivated by the desire to not transfer more power to the EU (39% very important, 37.5% important), uncertainty about the consequences of voting yes (44.3% very important, 32.9% important), and a lack of trust of politicians (34.4% very important, 32.2% important). Overall, most voters agreed that removing the opt-out was important for Danish security (40.5% agreed versus 27.8% disagreed).

The data supports the conclusion that arguments about solidarity and Danish influence resonated amongst voters. Given that the yes-side emphasized both the intergovernmental nature of EU defense cooperation and the relatively minor scale of current operations, this can have enabled Danish voters who are otherwise skeptical about ‘more EU’ to focus more on solidarity with EU partners during the crisis. The logic here is that given the intergovernmental nature of the area, Danes did not fear a massive transfer of sovereignty on the defence area, as the country through a formal veto option could keep the developments ‘under control.’ This also suggests that it would be a mistake to think that Danes would be prepared to remove the euro and JHA opt-outs, given that both involve supranational cooperation in sensitive issue areas.

References

Beach, D. (2016). Undersøgelse om danskernes holdninger til retsforbeholdet. Survey implemented by Epinion, Fall 2015.

Beach, D. (2018). Referendums in the European Union. In Oxford Encyclopedia of Politics. Oxford University Press.

Beach, D. (2021). If you can’t join them… Explaining No Votes in Danish EU Referendums. In The Palgrave Handbook of European Referendums. Palgrave Macmillan, 2021: 537-552.

Beach, D., Fenger, J., Finke, D., Pedersen, R.B., Senninger, R. (2022). Survey of Danish voting behavior during the 2022 defense opt-out referendum. Survey implemented by Epinion, Spring 2022.

Beach, D. & Finke, D. (2021). The long shadow of attitudes: differential campaign effects and issue voting in EU referendums. West European Politics, 44(7): 1482-1505.

Butler, G. (2020). The European Defense Union and Denmark’s Defense Opt-out: A Legal Appraisal. European Foreign Affairs Review, 25:1: 117–150.

DIIS (2019). European defense cooperation and the Danish opt-out. Report on the developments in the EU and Europe in the fields of security and defense policy and their implications for Denmark. Copenhagen: Danish Institute of International Studies

Hobolt, S. B. (2009). Europe in Question: Referendums on European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nissen, C. (2022, 2 May). Det danske EU forsvarsforbehold: Hvorfor, hvad og med hvilken betydning? hvorfor, hvad og med hvilken betydning, DIIS POLICY BRIEF.

Think Tank Europe (2022). Danmark har aktiveret EU-forsvarsforbeholdet 235 gange siden 1993.

Notes

citer l'article

Rasmus Brun Pedersen, Derek Beach, Roman Senninger, Jannik Fenger, Danish defense opt-out referendum, 1 June 2022, Jan 2023,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue