Empowering countries in their zero-carbon industrial journey

Issue

Issue #6Auteurs

Jean-François Mercure , Sebastian Valdecantos-Halporn , Étienne Espagne

Une revue scientifique publiée par le Groupe d'études géopolitiques

Climat : la décennie critique

Ten years after the Paris Agreement, climate change mitigation policy discourse remains detached from practical policy implementation. On the one hand, the economic and legal literature on climate change emphasizes the role of economy-wide carbon pricing and the reduction of fossil fuel subsidies as the most efficient and effective way to reduce emissions. 1 This stems directly from the polluter-pays principle whereby agents causing damage to third parties or the environment are expected to compensate society for it. On the other hand, successful policy experience for bringing technologies to markets points to policy instruments that reduce investment risk and create market volume which in turn reduces manufacturing costs. 2 This, however, requires productive capacities and therefore applies to lead markets for green technologies.

In stark contrast with traditional economic debates, actual climate action has triggered a global race towards technological dominance in the new green sectors, led by China, Europe and less so the US. 3 This is the result of comprehensive industrial policies characterised by state support to domestic green industries. China, Europe and the US have each in their own way deployed green industrial strategies, in a historical break with a long-standing tradition limiting state aid and state involvement. This race has resulted in a rapid decline in technology costs in those regions up to the point where parity is reached with their fossil equivalent.

In attempting to pursue their own zero-carbon industrial development, developing countries, however, face stringent state aid rules as part of global trade treaties. State aid, in which preferential treatment is given to domestic relative to foreign firms, whether for acting on climate or for boosting domestic competitiveness in international markets, generally breaches international trade and investment rules under WTO and other inter-regional or bilateral trade treaties. Therefore, green industrial policies frequently breach state aid rules. 4 However, state support of some form is usually necessary to develop new green domestic productive capabilities to supply domestically low-carbon solutions in the context of limited financial capacity to increase imports. Thus developing countries are constrained by trade agreements to remain reliant on imports for decarbonisation.

Emerging and developing countries also have limited capacity to join the green technological race as they face structural challenges limiting their access to finance. Beyond the trade and investment rules, irrespective of whether carbon is priced, climate action is largely hampered by lack of financial resources 5 , excessive financial risk 6 and limited productive capacity for low-carbon technologies and solutions that are increasingly cost-competitive elsewhere 7 . Developing countries notably face limited capacity to import zero-carbon technologies to reduce their emissions due to limited availability of hard currency, while foreign investors are deterred by currency risk. 8

Currency risk arises when investment is made in foreign currency, but revenues accrue in domestic currency, and the recipient domestic industry or the government assumes the currency conversion risk. Under adverse exchange rate fluctuations, domestic companies or the government with external debt positions could face foreign currency liquidity problems, leading to currency devaluation in a vicious cycle. Meanwhile, increased imports in the form of zero-carbon technologies can deteriorate the current account balance in the absence of compensating exports, which also increases risks of currency devaluation.

The result is that developing countries face a twin challenge: limits to accessing low-carbon technologies due to lack of finance and unsustainability of their current account, and limits to fostering domestic green industrial development due to trade agreements proscribing state aid, restricting their options for climate action.

I – Understanding currency and sovereign risk in the context of climate action

Green industrial policies have underpinned most zero-carbon technological progress to date and have been largely financed in domestic currency in advanced economies. This has been achieved using either dedicated public financing and regulatory mechanisms, development banks, investment funds or other forms of allocation of financial resources. 9 Successful industrial policies include programs that mitigate investment risk and create bankable volumes of low-carbon projects, bringing their costs down to or near parity with fossil fuels, and pushing them towards mass markets. Advanced economies use and issue so-called “hard” currencies, characterized by low liquidity premia and easily convertibility into any other type of currency, facilitating the import of green technologies where they are not available domestically. Hard currencies acquire their status by their use in the trade of goods and services, the depth of the financial markets and the perceived trust in their institutions.

In emerging and developing countries, financing zero-carbon investment using domestic currency and financial markets is constrained due to limited domestic productive capacity for green technologies and limited convertibility of the local currency. Most developing and emerging countries possess relatively “weak” currencies, affected by limited convertibility for international financial transactions and face higher liquidity premia 10 . In countries of limited domestic productive capabilities for green technologies, zero-carbon investments rely on imported productive capital and intermediate goods, requiring hard currency to support their transition. This may lead these countries to increase their level of external debt, competing with other basic needs such as importing medical equipment or IT components. Their balance of hard currency flows constrains their pace of transition towards net-zero, 11 unless they can increase exports, typically consisting of primary commodities including fossil fuels.

Sovereign risk, the risk of investing in particular countries, leads international investors to require higher returns, reflected in higher financing rates. In periods of low global interest rates, developing and emerging countries usually experience inflows of funds as international investors take advantage of differentials via ‘carry trade’. 12 In the absence of sufficiently stringent macroprudential frameworks, this can expose domestic agents in emerging economies to excessive external debt burdens that can become unsustainable when external conditions change, such as with an increase of interest rates in the US or Europe. Sovereign risk includes the possibility of global financial cycle shifts, capital flight, and turmoil in financial markets, interrupting investment. Together with currency risks, sovereign risks deter investment in many economically viable and necessary projects for a zero-carbon transition.

II – Realistic and effective climate action lies with green industrial policy

Addressing climate change becomes easier and cheaper the more we do it. The costs of key zero-carbon technologies have come down in recent years to achieve parity or near-parity with incumbent fossil fuel technologies. 13 This includes solar and wind energy, and electric vehicles. The bulk of investment bringing costs down have been made in leading markets, largely the EU, China and the US, opening access to effective climate action worldwide. However, not all countries can benefit due to financial constraints.

Zero-carbon productive capacity will be required to be built in developing economies beyond China, in order to achieve global climate action. To manage currency risks and to support resilient economic development away from unsustainable extractive models, developing countries must develop their own capacity to produce domestically decarbonization solutions. This suggests that zero-carbon solution manufacturing must spread outside of lead markets into developing economies. The upfront investment required for doing so could be substantial and building up competitiveness a significant challenge. But the long-term impact of sustained green industrial policy offers a way out of the cascading barrier of unsustainable reliance on imports, currency risk and lack of finance.

The transition cannot be achieved by advanced economies alone and developing economies risk being left behind with costly and inefficient fossil fuel technologies. High-carbon systems could become entrenched and increasingly difficult to phase out due to lack of hard currency financial resources, even when they are more expensive than renewable and low-carbon technology. Without real prospects of competitiveness with technologies from advanced economies, and with wavering fossil fuel markets worldwide, developing economies may find themselves in corner situations, with regards to foreign currency liquidity, in which ageing inefficient and polluting high-carbon capital cannot be replaced for cleaner capital.

III – Breaking the doom loop of currency risk and industrial under-development for climate action in emerging countries, the case of Brazil

There are not many ways to overcome the twin challenge of currency risk and industrial under-development in developing countries: it must involve innovative financing mechanisms and relaxing or re-interpreting state aid rules. Expecting advanced economies to finance the entire transition of developing countries is not a realistic prospect, as the former face their own domestic financing challenges for the transition. It is much less costly for advanced economies to relax stringent state aid rules as part of treaties with developing economies that proscribe trading partners from developing their own green industries. Meanwhile, the currency risk problem can be overcome with the use of appropriate currency hedging mechanisms, which can substantially reduce the cost of the zero-carbon transition.

Different de-risking strategies for investment in emerging and developing markets have recently been promoted, 14 but these are marred by potential contingent fiscal risks. In these approaches, private investors are rewarded for investing in risky markets via subsidies and guarantee mechanisms. Government budgets and development aid are expected to leverage private finance through targeted guarantee support and regulatory frameworks that allow for the emergence of investible asset classes, the exchange rate risk guaranteed by the public budget. However, in adverse scenarios, the transfer of risk from private to public budgets can become unsustainable. 15

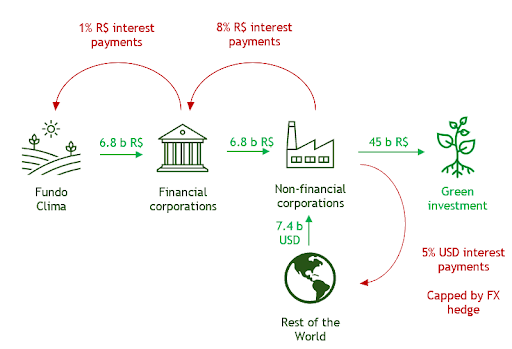

In contrast, Brazil has designed sustainable mechanisms to absorb currency risk in support of an ambitious climate action plan. 16 As part of the Ecological Transformation Plan 17 developed by the Brazilian Ministry of Finance in cooperation with the Interamerican Development Bank (IDB), the EcoInvest instrument 18 aims at managing the exchange rate volatility and boost persistently low levels of investment (See Figure 1). Low interest rates are guaranteed by a public fund, Fundo Clima 19 , for a series of targeted sectors and for companies that at the same time manage to attract external funding. A dedicated hedging mechanism ensures that these external funds are covered against excessive exchange rate volatility. While the uptake and success of these programs remains to be observed, this model could be considered more broadly across the developing world. It requires, however, an existing stock of foreign currency reserves, which is not available in many countries.

Figure 1: The blended finance instrument of the EcoInvest program, part of the Brazilian Ecological Transformation Plan

Conclusion

The twin barrier formed by currency risk and constraints to state aid from multilateral trade rules results in many countries becoming unable to either develop domestic capabilities to act on climate, or obtain those capabilities from abroad, and leads to limited capacity to act on climate change overall. This results in difficult debates over commitments from advanced economies for financial support to developing economies that have, up to now, been vastly insufficient to address the magnitude of the climate problem. But the problem may well be seen using the wrong lens, since empowering countries to develop profitable domestic zero-carbon industries does not necessarily require huge financial transfers from North to South. Instead, it requires developing facilities to absorb currency risk, and ways to allow investment in domestic productive capabilities that do not contravene trade agreements.

The creation of facilities and financial instruments to manage currency risk, along with innovative use of international trade and investment law to avoid costly court cases in the context of climate action could unlock ambitious action on climate change globally. The innovative Brazilian approach to mitigating currency risk within the framework of its Ecological Transformation Plan, demonstrated in the run up to COP30 in Belem, could offer a blueprint for a mechanism to mitigate currency risk and attract foreign climate finance. Meanwhile, making trade and investment law work for climate concerns rather than against is a critical element for a successful global zero-carbon transition. The essential goal is to empower countries to develop and scale zero-carbon productive capacities to meet climate challenges while contributing to resilient economic development.

Notes

- I. W. Parry, S. Black and K. Zhunussova, ‘Carbon Taxes or Emissions Trading Systems?: Instrument Choice and Design’, Staff Climate Notes, 2022(006)

- M. Grubb et al. (2021), EEIST report

- X. Li, M. Du, ‘China’s Green Industrial Policy and World Trade Law’, East Asia (2025)

- H. B. Asmelash, ‘Energy Subsidies and WTO Dispute Settlement: Why Only Renewable Energy Subsidies Are Challenged’, Journal of International Economic Law, Volume 18, Issue 2, June 2015, 261–285

- See IMF, “Global Financial Stability Report”, October 2023. [See Chapter 3: Financial Sector Policies to Unlock Private Climate Finance in Emerging Market and Developing Economies]. See also Climate Policy Initiative. Accelerating Sustainable Finance for Emerging Markets and Developing Economies, 2024.

- N. Ameli, O. Dessens, M. Winning et al., ‘Higher cost of finance exacerbates a climate investment trap in developing economies’, Nat Commun 12, 4046 (2021) ; A. Prasad, E. Loukoianova, A. X. Feng, and W. Oman. ‘Mobilizing Private Climate Financing in Emerging Market and Developing Economies’, Staff Climate Notes 2022, 007 (2022)

- B. Li, Q. Liu, Y. Li, S. Zheng, ‘Socioeconomic Productive Capacity and Renewable Energy Development: Empirical Insights from BRICS’, Sustainability, 15(7), 2023.

- J. Rickman, S. Kothari, N. Ameli et al., The ‘Hidden Cost’ of Sustainable Debt Financing in Emerging Markets, 17 October 2024.

- See M. Grubb et al, EEIST Report, 2021; G.F. Nemet, How solar energy became cheap: A model for low-carbon innovation, op. cit.

- D. M. Prates, ‘Beyond Modern Money Theory: A Post‑Keynesian approach to the currency hierarchy, monetary sovereignty, and policy space’. Review of Keynesian Economics, 8(4), 2020, 494–511.

- This is one dimension of a possible mid-transition trap. See E. Espagne, W. Oman, J.F. Mercure, R. Svartzman, U. Volz, H. Pollitt, E. Campiglio, Cross-border risks of a global economy in mid-transition (Vol. 184), International Monetary Fund, 2023.

- S. Filipe, J. Nissinen, M. Suominen, ‘Currency carry trades and global funding risk’, Journal of Banking & Finance, Volume 149, 2023.

- See M. Grubb et al, EEIST Report, op.cit. ; G. F. Nemet, How solar energy became cheap: A model for low-carbon innovation, op.cit.

- V. Laxton and E. Choi, Mobilizing Private Investment in Climate Solutions: De-risking Strategies of Multilateral Development Banks, WRI: World Resources Institute, 2024.

- D. Gabor, ‘The wall street consensus’, Development and change, 52(3), 2021, 429-459

- The macro and financial impacts of this mechanism have been assessed under the C3A (Coalition for Capacity on Climate Action) initiative together with the Ministry of Finance of Brazil

- Ecological Transformation Plan (2023)

- Eco Invest program (2023)

- https://www.bndes.gov.br/SiteBNDES/bndes/bndes_en/Institucional/Social_and_Environmental_Responsibility/climate_fund_program.html

citer l'article

Jean-François Mercure, Sebastian Valdecantos-Halporn, Étienne Espagne, Empowering countries in their zero-carbon industrial journey, Nov 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue