Northern Ireland Assembly Election, 5 May 2022

Clare Rice

Research Associate at the University of LiverpoolIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Clare Rice

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

The Northern Ireland Assembly

The Northern Ireland Assembly is a legislature within the United Kingdom (UK) with power to make laws on a range of devolved matters.

1

Since the signing of the Belfast/’Good Friday’ Agreement 1998 (GFA), the design of the political institutions in Northern Ireland requires that parties enter a power-sharing arrangement after elections. This is based on consociationalism, a model of power-sharing which is used in different forms across a number of settings internationally to manage conflict and division broadly defined. The rationale for its use in Northern Ireland stems from the territory’s history of protracted violent conflict, commonly referred to as ‘the Troubles’, which deeply engrained a division in Northern Ireland between, on the one hand, the Protestant/Unionist/Loyalist (PUL) community, and on the other, the Catholic/Nationalist/Republican (CNR) community. While clunky denotations of a complex and nuanced division, they capture the intermeshing of constitutional politics and religion within the historical conflict, while also demonstrating the deep and permeating bases of identity upon which the division proliferated. Power-sharing was the only potential form of governance that could command support in preventing one community holding a position of political dominance over the other, as was the case under the majoritarian system initially used following Northern Ireland’s creation.

This model entails a number of core features: a mandatory coalition of multiple parties within the Executive; proportional representation; and a mutual veto, which exists in the form of the Petition of Concern. In addition, cross-community votes can be held on some issues, which require support from a majority of unionist and nationalist representatives to pass. These operational elements are underpinned by a requirement for Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs) to officially designate as ‘Unionist’, ‘Nationalist’ or ‘Other’ when they are elected. The size of each group within the Assembly is significant, not least in determining which party can nominate to the positions of First Minister and deputy First Minister, which, despite their naming, are equal and form a joint office.

Each group comprises members of multiple political parties, and electoral competition is more common within these clusters rather than between them – for instance, parties at the opposite ends of Northern Ireland’s political spectrum are not in direct competition with each other for votes. The centre-ground — in this context meaning ’Other’ identifying parties — differs somewhat to this, as parties in this field attract voters from across the spectrum. However, the institutional structures prioritise the ‘Unionist’ and ‘Nationalist’ designations, these being the groups at the centre of Northern Ireland’s division.

The Assembly has faced many political difficulties and has been suspended on numerous occasions. Most recently, MLAs did not meet for three years between 2017-2020, and it is currently in the midst of a further period of crisis following the resignation of the First Minister in February 2022.

Context of the 2022 Election

It is necessary to reflect on some key events preceding the 2022 election in order to contextualise the results and their significance in certain regards.

Going into the election, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) was the largest party in the Assembly, and had been since 2003. In February 2022, the party resigned its First Minister from the Executive, setting the tone for the election — this action, the reasons for it, and its consequences for governance featured extensively in the election campaigns of all the parties. The resignation meant that ministers were unable to take any new or cross-departmental decisions, and only legislation already in progress within the Assembly was able to continue. The institutions operated in this shadow capacity until the Assembly dissolved ahead of the May election.

For the DUP, this decision was part of an ongoing protest at the Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland, part of the Brexit arrangements agreed between the UK and the EU. The Protocol has been a source of contention within Northern Ireland since it came into force at the start of 2021, particularly for the unionist community. The purpose of the resignation was explained by Party Leader, Sir Jeffrey Donaldson, as being a means of sending a signal to Westminster about the seriousness of the issues that exist with the Protocol and to ensure that unionist concerns would be addressed (Donaldson 2022). This established the Protocol as a key element in the DUP’s election campaign from the outset.

In a number of ways, the resignation was as much a reaction to external political and electoral pressures as it was an attempt to reflect concerns from within the unionist community, which were themselves informed by political responses to the Protocol. Electoral competition for unionist first preference votes and transfers, combined with the lingering impact of internal upheaval (Rice 2021) in the preceding year, necessitated that the party should take a very clear line on the Protocol issue. It opted to prioritise mitigating the potential movement of voters to the Traditional Unionist Voice (TUV) party in adopting a harder-line approach, calling for the Protocol to be ‘removed and replaced’ (BBC 2022) in contrast to the Ulster Unionist Party’s (UUP) position which was more in favour of the Protocol being retained and reformed.

An additional aspect to the election campaign was the question of whether or not the DUP would be returned as the largest party, and therefore, able to nominate again to the role of First Minister. Successive polling indicated a strong potential that Sinn Féin could be returned as the largest party for the first time, which entailed a symbolic significance both in terms of the nominal distinction it implies, and historically given that Northern Ireland was created with demographics that rendered this an unlikely outcome and was politically constructed to prevent it before power-sharing was introduced. This potential change was anticipated would encourage a strong vote for Sinn Féin in the election. Unionism’s divisions and its crowded electoral field meant that this posed an additional pressure point for the DUP in particular as the largest party, and part of the party’s election messaging was to encourage a consolidation of votes around it as a means to preventing a Sinn Féin First Minister.

From multiple angles, a lot of attention was placed on the DUP in the lead up to the election that meant the party was reliant on generating an appeal beyond its core voter base if it was to at least break even on its 2017 results. This was always going to be a challenging task and one made even more difficult with the decision to prioritise stymieing votes expected to flow to the TUV. This position also entailed that there was no obvious way that the party would return to power-sharing after the election given the reasons for the Executive being collapsed only three months previously, and as such, votes for the party would also be considered a signal of support to continue to pursue a hard-line approach on the Protocol.

Nationalist and ‘Other’ parties operated within a very different set of circumstances ahead of the election. For Sinn Féin and the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), broad agreement existed on the need for the Protocol’s full implementation following reform, so this was not a point of distinction. For Sinn Féin, it was not an election where additional seats needed to be gained; instead, the party needed to work to ensure its 2017 vote was sustained given the projected losses for the DUP. It ran a campaign that was more presidential in style, highlighting what its prospective First Minister could bring to the role, and focused on social issues, stating that the party’s constitutional aspirations for Irish reunification were not an immediate priority (Young 2022). The Protocol was also not a primary issue in the same way for the centre-ground parties. The Alliance Party, Green Party, and People Before Profit each had opportunities to capitalise on the dynamics at play elsewhere and, in different ways, all ran on platforms offering alternatives to Northern Ireland’s traditionally binary politics and its challenges.

The nationalist and ‘Other’ parties might have been similar in terms of the Protocol not dominating their campaigns, however the DUP’s actions in this regard shaped the way narratives and policy objectives of parties in this space were both articulated and received, meaning it became ubiquitous as an issue.

All of this made for an election that was difficult to predict, yet had the potential to alter the dynamics of contemporary politics in Northern Ireland as it was known.

A three-way split: Overview and analysis of the 2022 election results

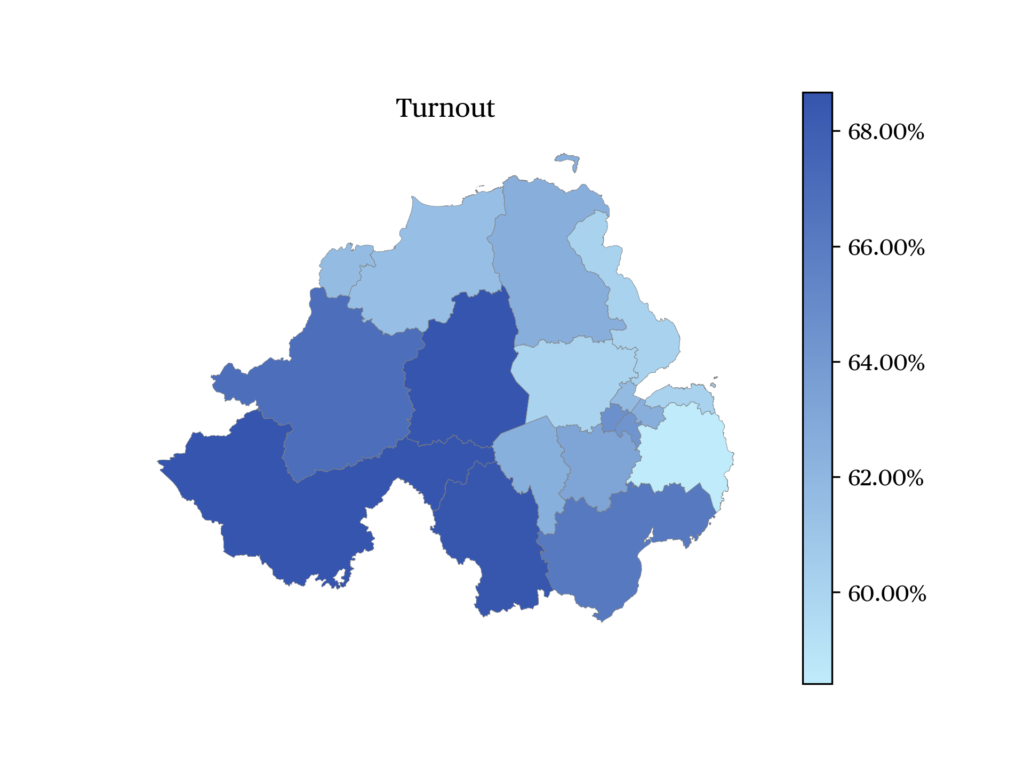

Turnout varied across the 18 constituencies.

2

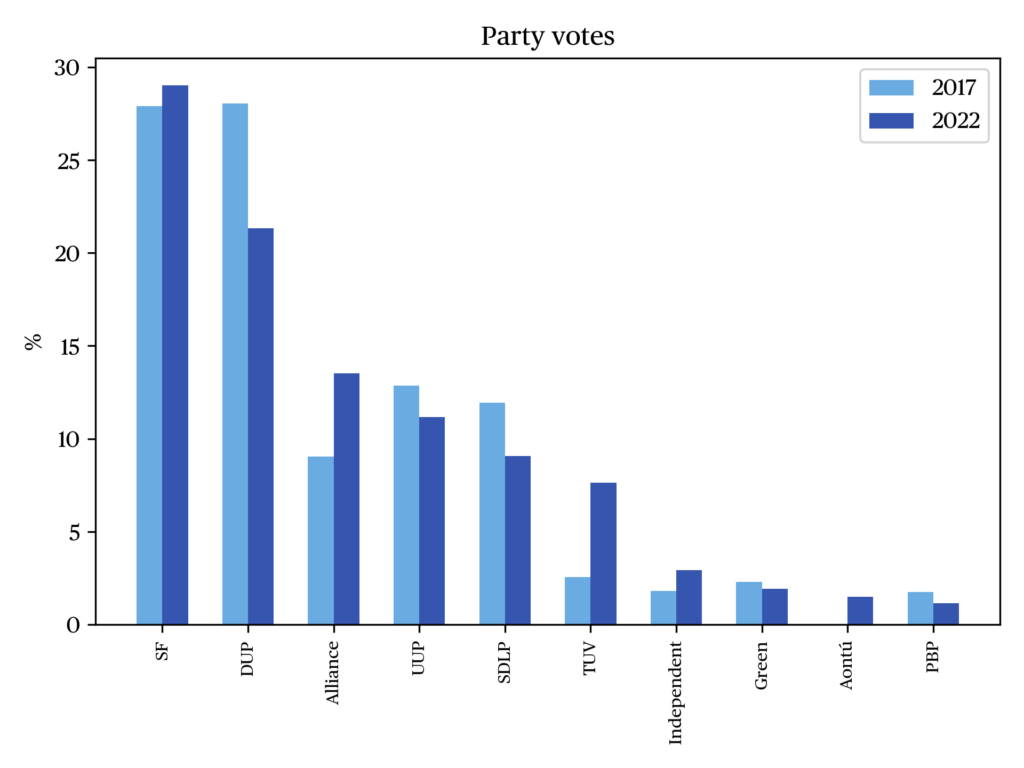

Overall turnout was 63.6%, down from 64.8% in 2017 which saw the highest recorded turnout since the first Assembly election, largely as a result of wider political factors at the time (RTÉ 2017). Higher turnout was seen mainly in constituencies where Sinn Féin topped the poll, due in part to two reasons: firstly, Sinn Féin has historically been adept at mobilising its voters; and secondly, the prospect of becoming the largest party and being able to nominate the First Minister further incentivised participation.

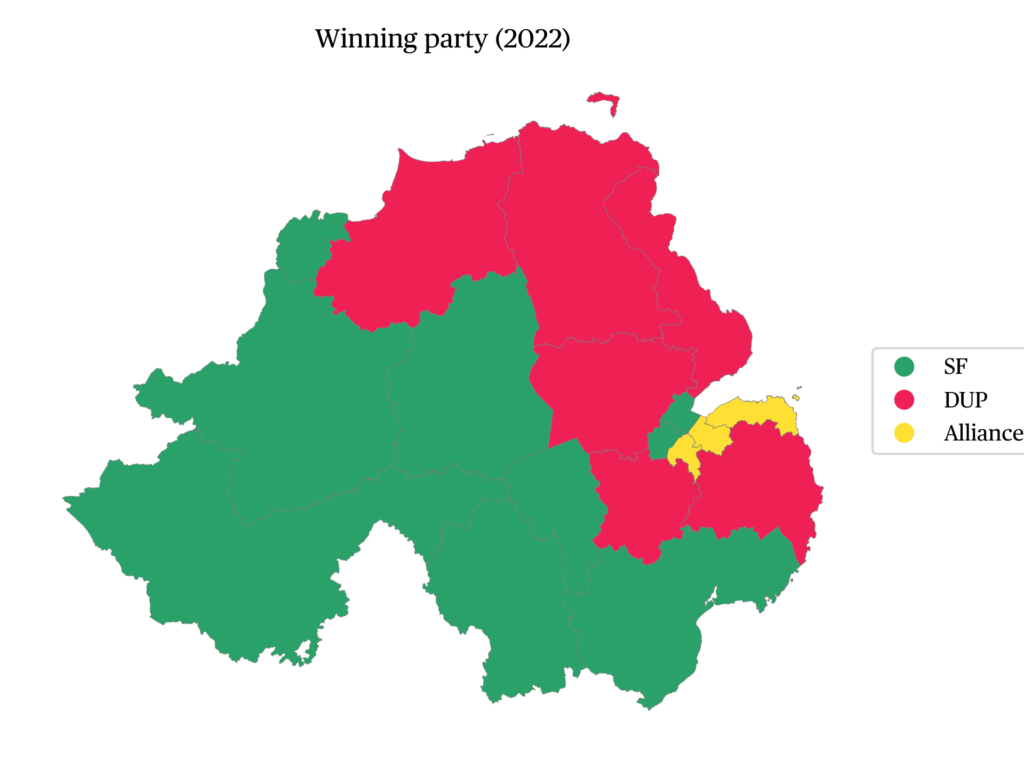

Sinn Féin topped the poll (i.e. achieved the most first preference votes; see map of parties with most first preference votes per constituency in “the data”) in 9 constituencies, the DUP in 6, and Alliance in 3. The TUV saw the biggest increase in vote share (+5.1%) while the DUP saw the biggest decrease (-6.7%). North Antrim is now the most diverse constituency in terms of political representation, with all representatives now from five different parties. 5 constituencies have 3 or more representatives from a single party, which in all these cases is Sinn Féin. The DUP now does not hold more than 2 seats in any constituency, but it does have the widest spread of all the parties, with MLAs in 17 of the 18 constituencies (Belfast West being the exception). The Alliance Party saw the biggest change in its portfolio, gaining seats in 4 additional constituencies compared to 2017.

It was a somewhat unremarkable election for Sinn Féin in terms of changes, however, its notable success was in retaining the same number of seats and increasing its first preference vote share by 1.1%. As a result, the party is now the largest in the Assembly, and for the first time, the First Minister will come from Sinn Féin. The party benefitted from the attention the symbolic significance of this position received during the election campaign, and by focusing on retaining seats rather than trying to increase (which could have overall resulted in losing seats), the party turned the unremarkable into a significant moment in Northern Ireland’s political history.

The DUP took a cautious approach and had 8 fewer candidates than in 2017. The success rate of its candidates was the highest of all the parties (83%), however, its share of first preference votes reduced by 6.7% with a total of 25 seats being won, a loss of three from 2017. Transfers from TUV voters were instrumental in mitigating the impact of the drop in first preference votes, a situation further aided by the TUV being a comparatively transfer-unfriendly party, which counterbalanced its 5.1% increase in first preference votes.

The Alliance Party saw a sizable increase in both its share of the vote and number of seats. It increased its first preference vote share by 4.5%, and more than doubled its representation in the Assembly, increasing from 8 to 17 seats. Crucially for the party, it made gains in new areas, including North Antrim and South Down for the first time. It also won a second seat in Belfast South, at the expense of the Green Party’s leader. The party is strongest in eastern constituencies, so it was notable also that it increased its vote share in western areas. Its gains came at the expense of multiple parties: the DUP, the UUP, the Green Party, and the SDLP.

The SDLP, having retained its 12 seats in 2017 despite a reduction of total MLAs from 108 to 90, saw an almost 3% reduction in its first preference votes. This was a difficult election for the party, which lost 4 seats including the incumbent Minister for Infrastructure in Belfast North, and its long-held second seat in South Down, both of which were historically safe SDLP seats. For the UUP, the picture was similar — it lost 1 seat, that of a party stalwart in East Antrim, and saw an overall decline in vote share by 1.7%.

Voting was strongest at three points on Northern Ireland’s political spectrum: its two extremes and the centre. Parties positioned elsewhere suffered as a consequence. The UUP and SDLP were Northern Ireland’s largest parties when the power-sharing institutions were established following the GFA; now they are the 4th and 5th largest parties respectively.

Of the 18 ‘Other’ seats won at this election, the Alliance Party holds 17, and People Before Profit holds 1. This swell for the Alliance Party came at the exclusion of Green Party representation entirely. While the Alliance Party has established itself in this election as the third largest party, the ‘Other’ designate group is not large enough to be considered to rival those of the ‘Unionist’ (37 MLAs, including 2 independent MLAs) and ‘Nationalist’ (35 MLAs) designations within the Assembly.

In summary, the election results reinforce that there is now a three-way split in Northern Ireland’s politics, with each pillar being dominated by a single party — a direct challenge to the binary politics that has dominated in the post-GFA era.

Aftermath

Since the election, the DUP has extended its protest at the Protocol to include a boycott of the Assembly. Without a Speaker in place, the legislature cannot function, and an Executive cannot be formed. Ministers from the previous mandate are currently continuing in post in a caretaker capacity, but their powers are limited.

What happens next is dependent almost entirely on factors outside Northern Ireland. Sufficient movement to encourage the DUP to return to Stormont was not anticipated before Boris Johnson left office, and his successor, Liz Truss, has given little indication that there will be any change in approach in this regard. Controversial legislation aiming to override aspects of the Protocol, introduced in Westminster in June 2022 by the new Prime Minister, who was tasked at the time with leading negotiations with the EU, has added to the complexity of this.

The new Prime Minister will have to find a way to strike a fine balance between addressing concerns within Northern Ireland to ensure power-sharing is restored, placating adversaries within her own party, and reaching negotiated solutions with the EU regarding the Protocol, in order to secure a pragmatic solution to the current situation. That will be no easy task, indicating that an indefinite period of political instability lies ahead for Northern Ireland.

Nota bene: These graphs/maps show first preference votes by constituency. Northern Ireland uses the Single Transferable vote (STV) system.

References

BBC (2022, 3 May). BBC Election Northern Ireland 2022: The Leaders’ Debate. BBC.

Burton, M. (2022). Northern Ireland Assembly Elections: 2022. Research Briefing. House of Commons Library. Online.

Donaldson, J. (2022, 3 February). Restoring Fairness. Speech. Online.

Rice, C. (2021, 21 July). DUP difficulties, governance in Northern Ireland, and the 2022 (?) election. PSA Blog. Online.

RTÉ (2017, 2 March). Key issues in the Northern Ireland election campaign. RTÉ. Online.

Young, D. (2022, 5 April). People are not waking up thinking about Irish unity — Michelle O’Neill. Belfast Telegraph. Online.

Notes

citer l'article

Clare Rice, Northern Ireland Assembly Election, 5 May 2022, Oct 2022,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue