Parliamentary Election in Cyprus, 30 May 2021 (I)

Vasiliki Triga

Associate Professor, Cyprus University of TechnologyIssue

Issue #1Auteurs

Vasiliki Triga

21x29,7cm - 102 pages Issue #1, September 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe: December 2020 — May 2021

On 30 May 2021, the 12th Parliamentary Elections since the island’s independence took place in the Republic of Cyprus (RoC). Parliamentary elections in Cyprus are traditionally of lower importance compared to the Presidential elections, since the President of the Republic wields executive power. Despite their lower salience, the Parliamentary elections are still considered a crucial barometer for the political parties’ power and influence in the Parliament, but also outside of Parliament. Parties’ parliamentary strength has an impact on how crucial issues, such as the economy, institutional matters, the next presidential elections and the so-called Cyprus problem are dealt with.

Context

The 2021 parliamentary elections turned out to be significant in various ways. They were the first elections to take place during the COVID 19 pandemic crisis, amidst growing economic uncertainty due to the lengthy lockdowns and a political and institutional crisis caused by the “golden passports” corruption scandal. The latter was heightened after an Al Jazeera television documentary in which the then speaker of the Parliament, Demetris Syllouris, and an MP from the opposition party AKEL appeared to operate as mediators for arranging the naturalization of a criminal Chinese businessman. This incident triggered a series of events: the resignation of the President of the Parliament, an interim investigation for numerous applications for a Cypriot passport, especially for applicants with obscure criminal records aided by prestigious law firms in Cyprus, the abolition of the specific naturalization scheme upon Brussels’ pressure and an overwhelming public anger. Against this background, the composition of a new parliament could have been a transformative moment with the entry of new political parties protesting against corruption and expressing indignation against the existing political system. The results, however, did not produce such a moment, since most of the new parties did not manage to pass the threshold of 3.6 percent and enter the House of Representatives, but instead confirmed the status quo in the Cypriot political context.

Although corruption was a flag issue during the campaign for many parties, especially the new ones, this was not truly the major concern of public opinion. Instead, opinion polls suggest that the economy, along with the classic Cyprus problem, were the most salient issues upon which the electorate formulated its vote choices (IMR, 2021 ; Cypronetwork, 2021). Against this background context the way to the election was long, intense and polarized. The parties and their candidates organized their promotion campaign events predominantly through social media since the lockdown did not allow for social events. This fact had two consequences: On the one hand, the use of social media for campaign reasons opened up new ways of communication and potentially created a new precedent for the use of new technologies in the forthcoming electoral campaigns in Cyprus. On the other, due to social media’s greater scope for interactivity, the campaign became toxic with the use of harsh language by candidates and party supporters, especially those of the new parties, while also providing a platform for the expression of generalized public anger and discontent.

The Candidates

In these elections there were 15 candidate parties/political formations and seven independent candidates. Eight new parties ran for the first time. Past electoral analysis (Triga, 2017) indicates that the Cypriot ideological space is structured upon two well-known axes of political competition. The first concerns the regulation of the economy, the classic cleavage between left and right. The second axis concerns culture and identity issues and incorporates the so-called Cyprus problem. The Cyprus problem is understood as the long-standing de facto partition of the island into a southern Greek Cypriot and a northern Turkish Cypriot part following the Turkish invasion and occupation of the northern part of the island in 1974. Since then, the Southern part of the RoC has been the only internationally recognized state, a fact that makes Cyprus the only EU member state with divided territory under military occupation. Below we briefly discuss the parties that run for the elections in relation to the two axes of the political space in Cyprus.

The so-called old parties were the following:

a) DISY (Democratic Rally — Δημοκρατικός Συναγερμός), with a classic right-wing ideological stance that holds the majority in the Parliament. DISY occupies its own distinctive policy space characterised by a consistent neo-liberal economic position and a more moderate cultural position (mostly because of its position on the Cyprus problem). The President of the Republic, Nicos Anastasiades, belongs to this party.

b) AKEL (Progressive Party of the Working People —Ανορθωτικό Κόμμα Εργαζόμενου Λαού) is a communist party (according to party’s declarations [Akel, 2019]) that adopts left-wing economic positions and is socially progressive. In these elections (as well as recent ones) AKEL has suffered a gradual loss of its electoral base. Yet it remains the biggest opposition party and has the most liberal stance on the Cyprus problem.

c) DIKO (Democratic party — Δημοκρατικό Κόμμα), the third biggest party, is rather centrist in terms of the economy but has taken a more nationalist turn vis a vis the Cyprus problem — a fact that has created tension inside the party and led to a split with the creation of a new party DIPA (Democratic Front — Δημοκρατική Παράταξη) under the leadership of DIKO’s former leader, Marios Garoyian.

d) ELAM (National Popular Front — Εθνικό Λαϊκό Μέτωπο), a far-right party, authoritarian in terms of cultural issues and ultra-nationalist vis a vis the Cyprus problem. ELAM appears quite centrist on the economy, which is quite common among many other far-right parties in Europe who have a populist stance and support policies that are against austerity or privatizations, for example.

e) EDEK (Unified Democratic Union of the Centre —Ενιαία Δημοκρατική Ένωση Κέντρου) is a socialist party, left on the economy but on the conservative side with respect to cultural issues, especially the Cyprus problem: the party denounces the bizonal bicommunal federation. EDEK, despite its consistent decline in recent elections, managed to maintain its fifth position in these elections.

f) KOP (Movement of Ecologists-Citizens’ Cooperation — Κίνημα Οικολόγων Συνεργασία Πολιτών), known also as the Greens, is an overall centrist party promoting a democratic renewal with the collaboration of civil society. However, its positions toward the Cyprus problem remain a bit confusing since the change in its leadership.

g) The Solidarity Movement (Κίνημα Αλληλεγγύη), which first competed in the 2016 parliamentary elections, is a fringe party created by an ex-member of DISY following disagreement with President Anastasiades on how the Cyprus problem was being deal with. The party gained three seats in the 2016 parliamentary elections following a hard line on the Cyprus problem by opposing the model of bi-zonal, bicommunal federation and disputing the overall political establishment.

The remaining eight parties were all newly created. Except for DIPA that as mentioned above was rather moderate on the economy and the cultural axis, the rest six parties were anti-status quo, and mobilized on a anti-corruption agenda. Most of them (apart from Famagusta for Cyprus (Αμμόχωστος για την Κύπρο) also adopted a nationalistic stance on the Cyprus problem (e.g. Awakening 2020 (Αφύπνιση 2020), Active Citizens: United Cypriot Hunters (Ενεργοί Πολίτες: Κίνημα Ενωμένων Κυπρίων Κυνηγών), Independents: Generation Change (Ανεξάρτητοι: Αλλαγή Γενιάς), Peoples Breath (Πνοή Λαού), Animal Party Cyprus (Κόμμα για τα Ζώα Κύπρου), Patriotic Coalition (Πατριωτικός Συνασπισμός).

Election Results

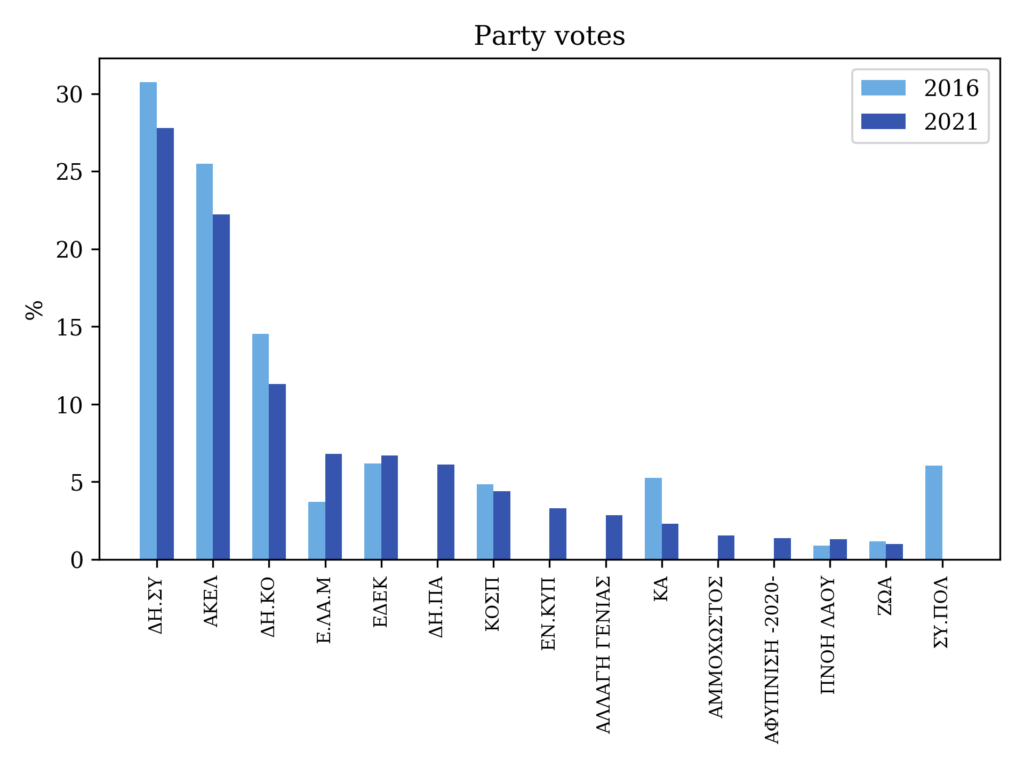

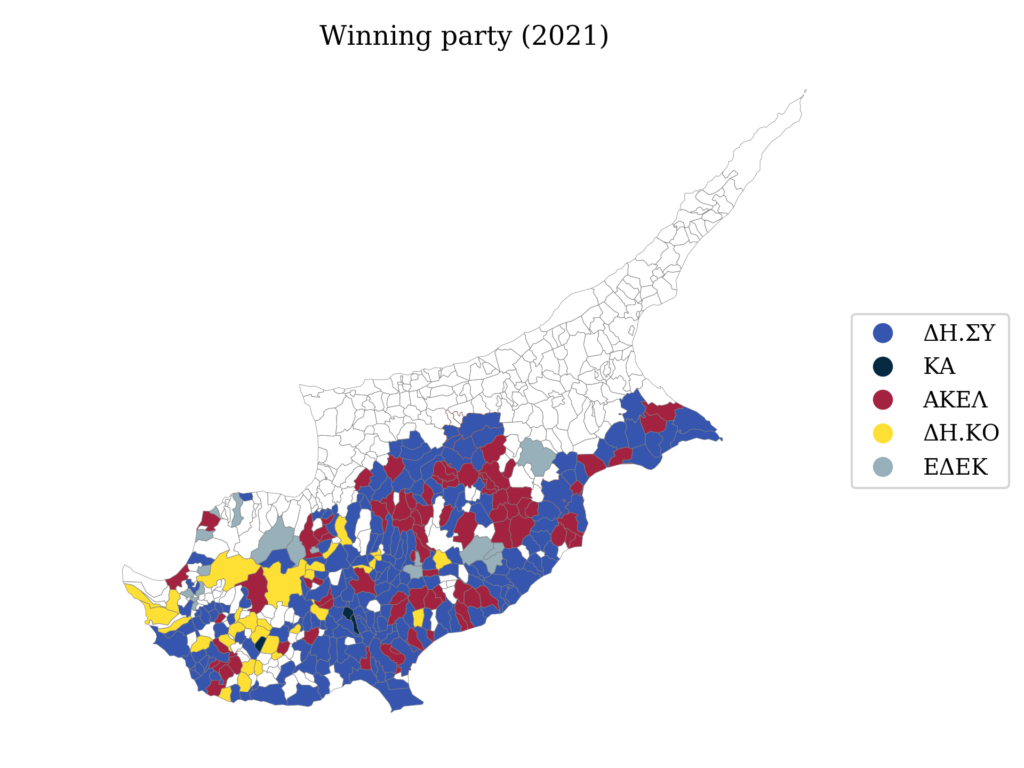

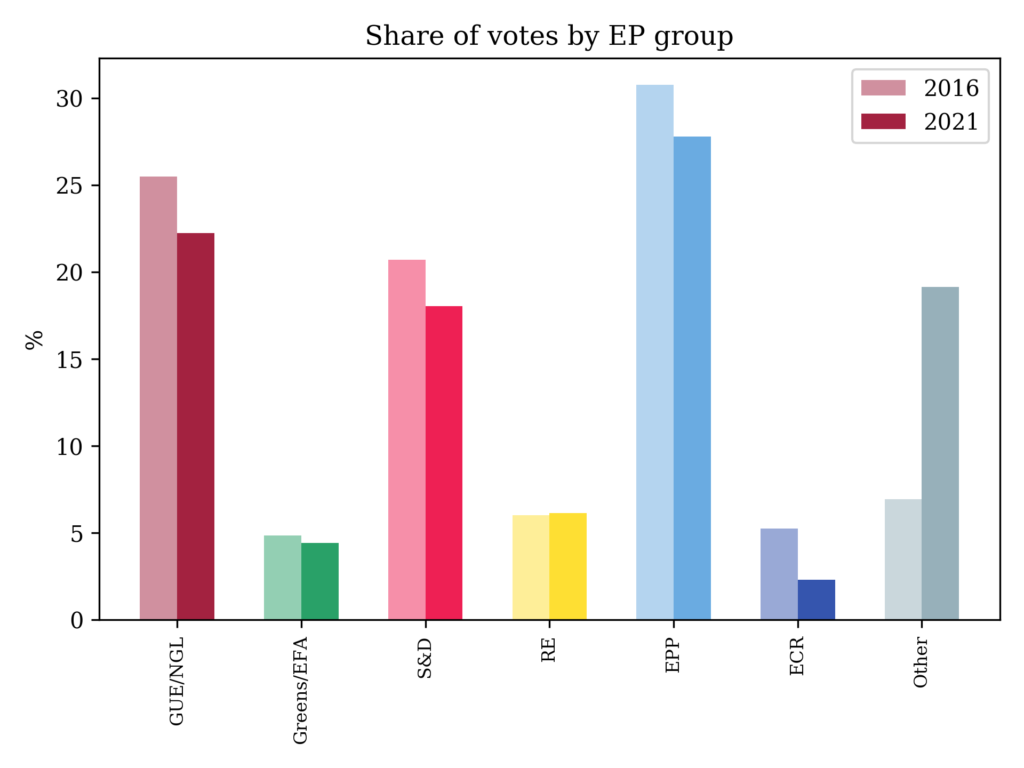

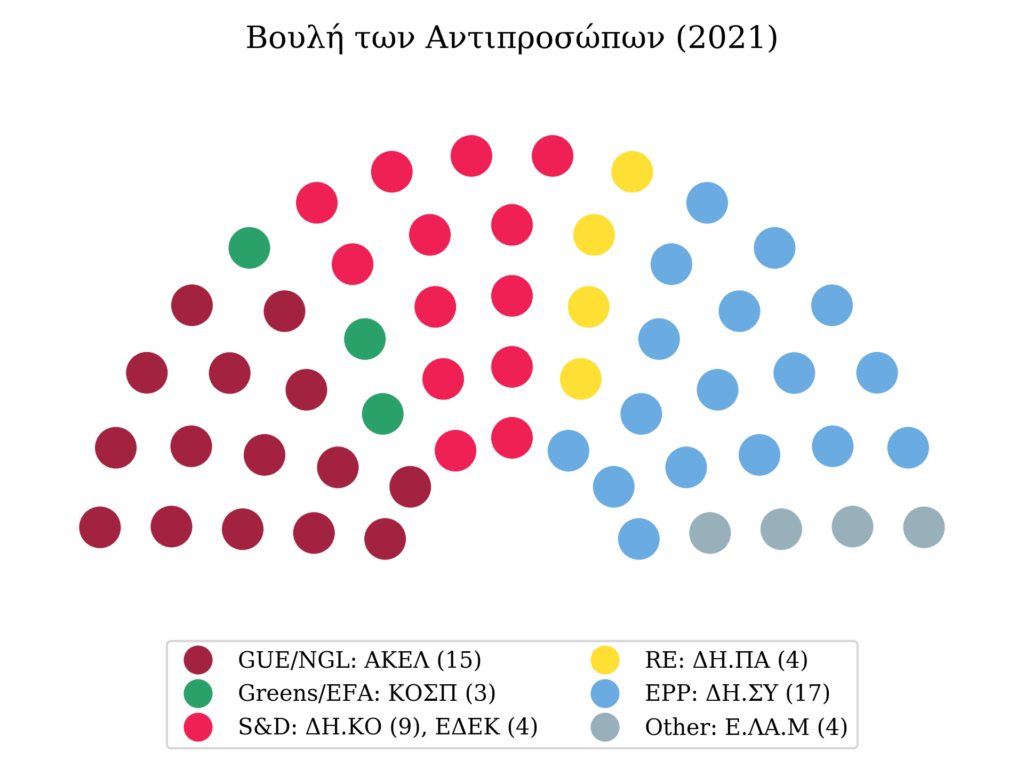

Turning to the election results (see “data” panel), we immediately notice that it was a loss for the opposition rather than for the incumbent, who incured losses. Incumbent parties are frequently “punished” by election outcomes — this was also the case for DISY. The party lost almost 3 percent of its vote share and one seat, having gained only 27.8 percent of the overall votes, at a historical low. However, it remained the first party and held its power. Relatively speaking, this is not a bad outcome for DISY, given that the party was directly involved in the golden passport scandal and has been in power for almost eight consecutive years. Another observation is that AKEL faces the biggest setback of all parties. This vote “hemorrhage” had started already after the defeat of its candidate for the Presidential elections in 2013. Since then, the party seems unable to recover from the perceived failures of Chirstofias presidency (an AKEL leader for 21 years) and capitalize on public discontent of the government’s policies and scandals. The very centralized party approach vis a vis its members and an overall lack of modernization of its discourse appear as ineffective strategies for bringing voters back to the party.

In general, all the existing parties (except for ELAM) lost votes compared to the 2016 parliamentary elections (a phenomenon that emerged in the last 10-year period). More specifically, the two main parties have lost almost 17 percent of their vote share, with their combined electoral strength now accounting for 50 percent of the total vote share (as opposed to 56.4 percent in 2016 and 67 percent in 2011). The notable exception was the far-right party of ELAM, which turned out to be one of the biggest winners. Overall, the new parties managed to attract 14 percent of the vote share by adopting positions that were held traditionally by DISY and DIKO. However, despite their combined gains, apart from DIPA, seven of the new parties did not manage to cross the 3.6 percent (since 2015) threshold to enter parliament.

The parliamentary elections result re-inforced three political phenomena that have become apparent since 2011 and will undoubtedly shape the dynamics of the forthcoming 2023 Presidential elections:

- The growth in voters’ abstention as a systemic feature of the present political context in Cyprus. Abstention rates show a raising trend in Cyprus politics. In the immediate period before the onset of the Great Recession, turnout was about 89 percent (2006), to be compared to the 65 percent in 2021. Although it follows a wider European tendency since the early 2000s, is rather unusual for Cyprus. It is worth mentioning that in these elections. on top of the 34.3 percent that abstained from the ballots, 80.000 new voters did not even register to vote. Analysts connect this trend with the abolition of compulsory vote in Cyprus (legally in 2017, yet the turning point was when Cyprus joined the EU in 2004), and most importantly with a generalized feeling of political apathy, distrust and lack of interest in politics on the part of the electorate.

- The continuous party fragmentation, also related to electoral dissatisfaction. The trend is linked further to the weakening of the two major political parties, DISY and AKEL, which are perceived as unaccountable political formations. Hence, we observe the emergence of new, non-mainstream parties that put forward anti-status quo and anti-corruption manifestos. Although this phenomenon is not new, we do observe that these new parties tend not to last, as shown by the example of Solidarity Movement, which lost its representation in 2021. An interpretation could be that the stressful period of the pandemic re-booste indignation and distrust towards the capacity of “old” parties to manage crises (presently the pandemic), a sentiment which was expressed by the new political parties.

- The far-right party ELAM consolidated itself, and is now the fourth political power in the Cyprus political system. After its first appearance in the 2009 European elections (polling a mere 0.22 percent), ELAM has been steadily and gradually increasing its power. Although ELAM first appeared as a protest party within a wider context of political disappointment, it managed to consolidate its position without the support of its mentor and brother party Golden Dawn in Greece (that latter has been largely disbanded following the imprisonment of many of its elected MPs). Explanations for ELAM’s rise can be attributed to the abandonment of its radical actions and its professionalized campaign strategies, which contributed to its incorporation in the political system. It is indicative that a party representative commented ELAM’s performance on a TV show on election night by using the phrase “democracy won.”

Bibliography

IMR (2021, March-May). Poll for RIK. University of Nicosia.

Cypronetwork (2021, April). Poll for Omega Tv.

Triga, V. (2017). Party changes in post-bailout Cyprus: The May 2016 Parliamentary Elections. South European Society and Politics 22:2, 261-278.

Akel (2019). Communist party of Cyprus : Akel. 93 years of struggles for Cyprus and its people. Online.

The Data

citer l'article

Vasiliki Triga, Parliamentary Election in Cyprus, 30 May 2021 (I), Sep 2021, 71-73.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue