Parliamentary Election in Cyprus, 30 May 2021 (II)

Gilles Bertrand

Lecturer, University of BordeauxIssue

Issue #1Auteurs

Gilles Bertrand

21x29,7cm - 102 pages Issue #1, September 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe: December 2020 — May 2021

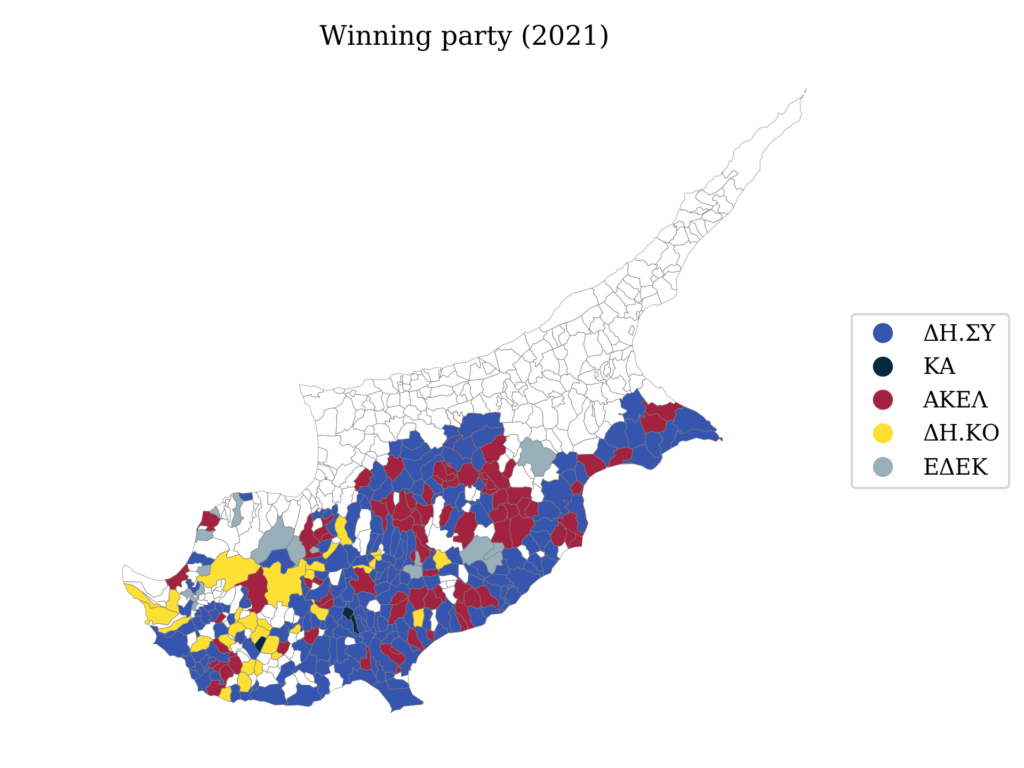

The territorial framework

A British colony until 1960, the island of Cyprus experienced an “intercommunal” conflict 1 which led to its partition in 1974. Despite a dozen rounds of negotiations since then, the conflict is “frozen” without a lasting solution (Bertrand, 2017). The island is thus divided into:

- A southern zone representing 58% of the territory, with 850,000 “Greek” Cypriots (Greek-speaking Orthodox), minority Christians (Armenians, Catholics and Maronites), a few hundred “Turkish” Cypriots (Muslims) and non-citizen residents living under the authority of the Republic of Cyprus (RC), the only state internationally recognised as sovereign on the island;

- A Turkish-occupied northern area, representing 36% of the territory, with an estimated population of 260-330,000 “Turkish” Cypriots but also Turkish nationals, some of whom also enjoy citizenship of the self-proclaimed Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), as well as several hundred “enclaved” Greek Cypriots; 2

- The remaining 6% of the territory is almost equally divided between two British Sovereign Base Areas (SBAs) and the buffer zone between the two zones in the north and south, which is under the control of the United Nations Force (UNFICYP).

As the partition was illegal, the RoC maintained the six original electoral districts, while Kyrenia’s electoral district is entirely in the north and Nicosia and Famagusta’s in part. Greek Cypriots who were resident in these constituencies before 1974, but who took refuge in the south at the time of partition, continue to vote there fictitiously (the polling stations being “delocalized” to the south).

The constitutional framework

The RoC has a strong presidential system. The President of the Republic is elected for five years by direct universal suffrage. He appoints the ministers, who are not accountable to the House of Representatives (the only chamber of parliament). The duration of a legislature is also five years, but it does not match with the presidential term — there is a three-year gap, due to the conflict (1965 presidential elections postponed to 1968, 1975 legislative elections postponed by one year). The 1960 Constitution provided for the election of deputies by separate community electorates. Greek Cypriots and Christian minorities elect 56 deputies; Turkish Cypriots are supposed to elect 24 deputies, but their seats have remained vacant since the conflict in late 1963. However, following a 2004 ruling by the European Court of Human Rights, a 2006 law allows the 400 or so Turkish Cypriots living in the south to register on the Greek Cypriot electoral roll and thus participate in the election of 56 deputies. Finally, three deputies are elected by the members of the three Christian minorities (who therefore vote twice) but only have an advisory role on issues concerning minorities (e.g. education).

Members of Parliament are elected according to a system of proportional representation with limited preferential voting (1979, modified in 1995 and 2015). The distribution of seats is done in two steps. A first distribution allocates as many seats as each list has obtained votes, multiplied by the electoral quotient (resulting from the division of the number of valid votes by the number of seats) of the constituency. The list leaders and then the candidates with the highest number of preferential votes are selected first, followed by the other candidates. A distribution of the remainders then takes place, but in order to participate, the party must have obtained 3.6% of the votes cast nationally. This threshold is raised to 10 or 20% for coalitions of two or more parties.

| Electoral constituency | Seats | Possible preferential votes |

| Lefkosia (Nicosie) | 20 | 5 |

| Lemesos (Limassol) | 12 | 3 |

| Ammokhostos (Famagouste) | 11 | 3 |

| Larnaca | 6 | 2 |

| Paphos | 4 | 1 |

| Kerynia (Kyrenia) | 3 | 1 |

The Greek Cypriot political landscape

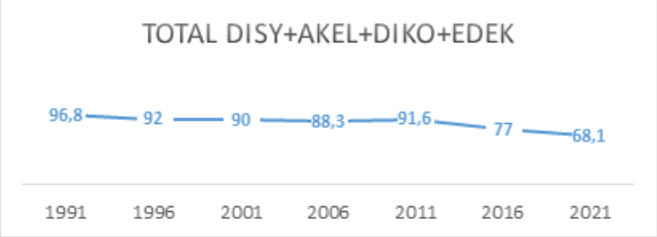

Composed mainly of 4 large parties which totalled 97% of the votes during the 1991 legislative elections and still 68% in 2021, it is still largely marked by intra- and inter-community conflict, but also by a clientelist system identifiable in particular by the recruitment in the civil service of affidavits of the parties in power. Thus, the results of each party in the legislative elections seem to play a role in the distribution of public jobs during the following term (Faustmann, 2010).

AKEL (Ανορθωτικό Κόμμα Εργαζόμενου Λαού, Workers’ Reform Party), founded in 1941, is actually the Communist Party (founded in 1926, banned under that name by the British in 1933). It favours reunification and thus a compromise with the Turkish Cypriots, but called for a vote against the UN plan in 2004 and failed to reach an agreement during the presidency of its former general secretary Dimitri Christophias (2008-2013). DISY (Δημοκρατικός Συναγερμός, Democratic/Republican Rally — the distinction does not exist in Greek), founded in 1976, brings together different sensibilities: nationalists, conservatives, liberals. It is one of the heirs of the nationalist current which bears a heavy responsibility in the conflict. Its leaders, Glafcos Clerides and then Nicos Anastassiades, the current President of the Republic, voted in favour of the UN plan in 2004, but some of their activists and voters are ultranationalists. DIKO (Δημοκρατικό Κόμμα, Democratic/Republican Party) is more liberal than DISY but no less nationalistic: its leader, President Tassos Papadopoulos (2003-2008), is primarily responsible for the failure of the UN plan (76% of Greek Cypriot votes in opposition in the 2004 referendum). At the time, he claimed that he would negotiate a “better plan.” His son Nikos, the current leader of DIKO, is equally maximalist. EDEK (Ενιαία Δημοκρατική Eνωση Κέντρου — Κίνημα Σοσιαλδημοκρατών: Unitary Rally of the Democratic Centre -Movement of Social Democrats), founded in 1969, certainly belongs to the Socialist International, but is also very nationalistic and maximalist, and not too open to dialogue with Turkish Cypriots.

b • Total vote share of the four large historical parties of the RoC, 1991-2021

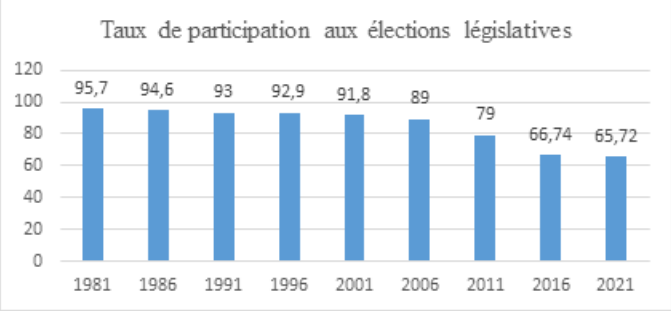

c • Turnout in general elections in the RoC, 1981-2021

These four parties have been in relative decline for the past thirty years (Figure b). The political scene only started to open up after the 2001 parliamentary elections (4 MPs belonging to 4 new parties, including environmentalists). Nevertheless, the phenomenon remained very marginal until the financial crisis of 2013.

The crisis of representation, born of the 2013 crisis, still ongoing

As a member of the European Union since 2004 and the Eurozone since 2008, the RoC suffered the consequences of the 2008 global crisis, the debt crisis and the subsequent crisis of confidence in the EU institutions and the local political class (Karatsioli et al., 2014). However, the financial crisis only erupted in 2013 when the fragility of Cypriot banks, highly exposed to Greek debt, holing bad debts and at the heart of a real estate bubble, forced the European Central Bank to intervene and the European Council to impose drastic measures on the RC. However, the ensuing recession lasted only two years and, despite the persistence of some difficulties, the Greek Cypriot economy recovered faster than expected (Hardouvelis & Gkionis, 2016). However, the crisis has severely eroded confidence in the political class, a phenomenon aggravated by corruption scandals (Assiotis and Krambia-Kapardis, 2014), most recently the affair of the “golden passports” granted opaquely to non-EU nationals in exchange for sometimes dubious investments, and the total lack of progress in the negotiations for reunification.

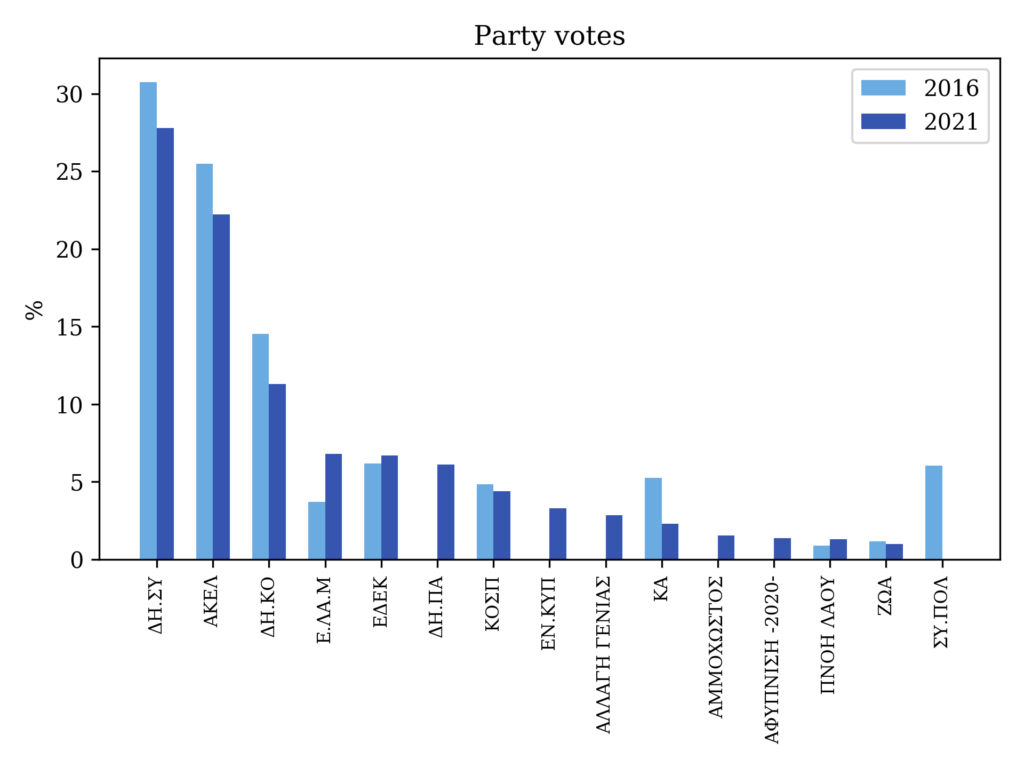

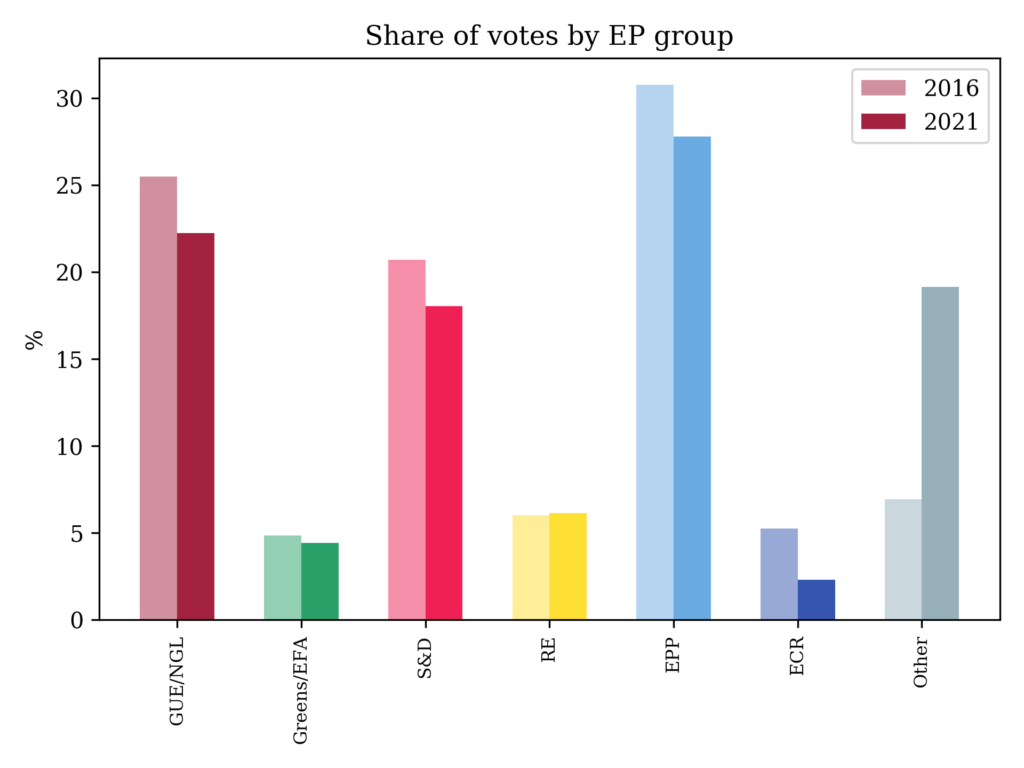

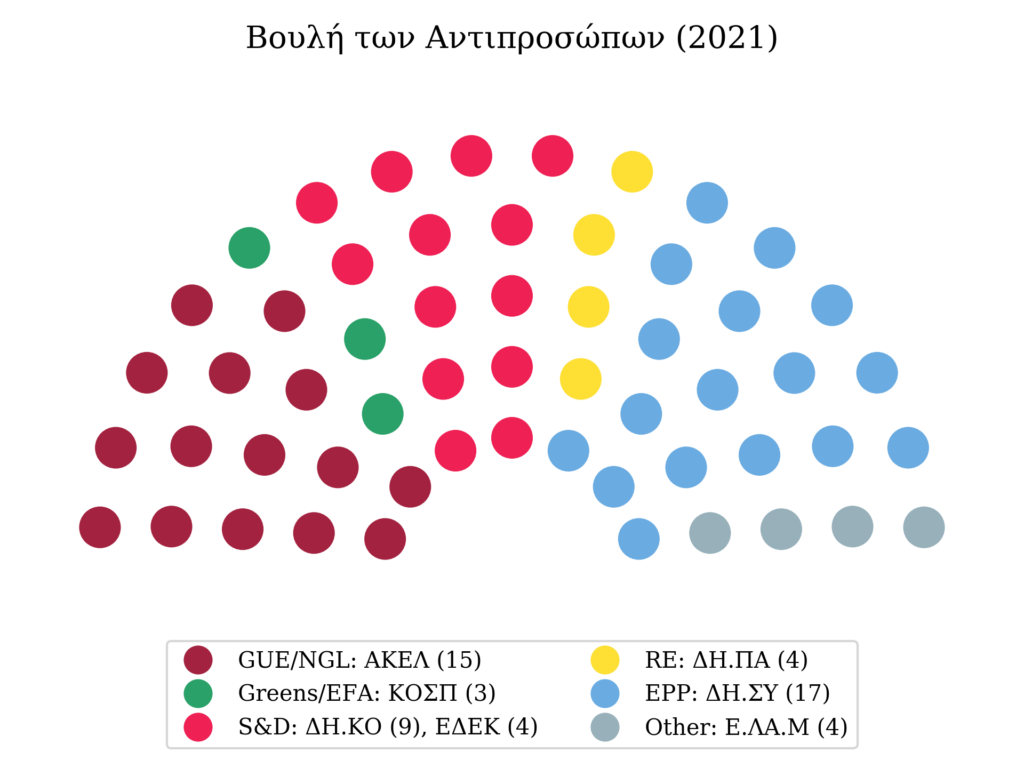

| Votes 2021 | % 2021 (% 2016) | Seats | |

| AKEL (communist) | 79 913 | 22,34 (25,67) | 15 (-1) |

| DISY (federalist right) | 99 328 | 27,77 (30,7) | 17 (-1) |

| DIKO (anti-federalist right) | 40 395 | 11,29 (14,49) | 9 |

| EDEK (anti-federalist left) | 24 022 | 6,72 (6,18) | 4 (-1) |

| DIPA (diss. DIKO, pro-negociation) | 21 832 | 6,10 | 4 |

| ELAM (nationalist) | 24 255 | 6,78 (3,7) | 4 (+2) |

| Ecologistes (anti-federalist) | 15 762 | 4,41 (4,8) | 3 (+1) |

| Votes obtained by parties represented in Parliament | 305 507 | 85,41 (96,9) | |

| Turnout | 366 608 | 65,72 (66,74) | |

| Registered voters / Total seats | 557 836 | 56 |

Voter turnout fell sharply in 2011 and 2016; it stabilised in 2021. Unsurprisingly, surveys show a link between abstention and the decline in citizens’ identification with the four historical parties; as elsewhere, young people abstain the most (Kanol, 2013).

Correlatively, the four major parties (AKEL, DISY, DIKO and EDEK), which had always received more than 90% of the votes in the legislative elections (except in 2006: 88.3%), received only 77% in 2016 and 68% in 2021.

The new parties are the very relative winners of the crisis of political representation. In fact, 8 of the 10 new parties that have obtained at least one MP since 1996 are the result of dissidences from the big 4, and have disappeared one after the other. The only one still active is DIPA (Δημοκρατική Παράταξη, Democratic Front), founded in 2018 by DIKO cadres challenging the current party leadership. Like all previous breakaway parties, DIPA only relatively endangers the party it split from: DIKO kept the 9 MPs it had in 2016, despite losing 10,000 votes from one election to the next.

Two parties are exceptions to this rule: the environmentalists, and the far right under the banner of ELAM (Εθνικό Λαϊκό Μέτωπο, National Popular Front), established in 2008 as the Cypriot branch of the Greek party Golden Down (Katsourides, 2013). These are representative of two relatively new and growing political currents in most EU member states. Having won their first parliamentary seat in 2001, the Greens have 3 seats twenty years later… This is hardly a meteoric rise, especially as the party lost 1200 votes between 2016 and 2021. Of course, the Western European green parties have not progressed very fast either. The Greek Cypriot ecologists however may suffer from their peculiar positioning: they are not very open to negotiations with the Turkish Cypriots, which is surprising for a party claiming to be on the left of the political spectrum, and likely to confuse young voters. ELAM, on the other hand, has enjoyed a positive dynamic in the last decade: a small group in 2011 (4354 votes), it obtained 13040 votes in 2016 (2 MPs) and almost doubled its score in 2021.

Conclusion

The May 2021 elections are characterised by a high abstention rate and a historically low score of the four major parties, that have shared almost all the seats in parliament since 1976. Clearly, these results reflect exasperation with the governing parties, which did not anticipate or manage the 2013 crisis well. The results also reflect a certain weariness with the political oligarchy. However, it should not be forgotten that the most important election in the RoC is the presidential election, which will take place in February 2023.

Bibliography

Assiotis A. and Krambia-Kapardis M. (2014). Corruption correlates: the case of Cyprus. Journal of Money Laundering Control, 17 (3).

Bertrand G. (2017). Chypre : trop de négociations ont-elles tué la négociation ? Confluences Méditerranée, n°100.

Bertrand G. (2005a). Chypre. In Y. Déloye (dir.). Dictionnaire des élections européennes. Paris : Economica.

Charalambous G. (2012). Le Parti progressiste du peuple travailleur (AKEL). Un profil sociopolitique. In J.-M. De Waele & D.-L. Seiler, Les Partis de la gauche anticapitaliste en Europe, Paris : Economica.

Charalambous G. and Christophorou C. (dir.) (2016). Party-Society Relations in the Republic of Cyprus. Political and Societal Strategies. London : Routledge.

Copeaux É. and Mauss-Copeaux C. (2005). Taksim ! Chypre divisée. Lyon : Ædelsa.

Faustmann H. (2010). Rusfeti and Political Patronage in the Republic of Cyprus. The Cyprus Review 22 (2).

Hardouvelis G. A. and Gkionis I. (2016, December). A Decade Long Economic Crisis: Cyprus versus Greece. Cyprus Economic Policy Review, University of Cyprus, Economics Research Centre, vol. 10(2), pp. 3-40.

Karatsiolis et al. (2014). Dossier sur la crise mondiale et ses conséquences à Chypre. Cyprus Review, 26 (1).

Katsourides Y. (2013). Determinants of Extreme Right Reappearance in Cyprus: The National Popular Front (ELAM), Golden Dawn’s Sister Party. South European Society and Politics, 18 (4).

Kanol D. (2013). To Vote or Not to Vote? Declining Voter Turnout in the Republic of Cyprus. The Cyprus Review, Vol. 25, No. 2.

Rossetto J. (2012). Le statut constitutionnel de la République de Chypre. In Rossetto J. and Agapiou-Joséphidès K. (dir.) (2012). La singularité de Chypre dans l’Union européenne. Diversité des droits et des statuts. Paris : Mare & Martin.

The Data

Notes

- This is a particularly problematic label (Bertrand, 2005a). It would be more accurate to speak of a conflict between Greek-Cypriot and Turkish-Cypriot nationalist political-military elites and factions, with the population either supporting or suffering (and often both) from the belligerents (Copeaux and Mauss-Copeaux, 2005). The Greek and Turkish states are also involved in the conflict.

- These are Greek Cypriots who remained in the north despite the Turkish occupation.

citer l'article

Gilles Bertrand, Parliamentary Election in Cyprus, 30 May 2021 (II), Sep 2021, 74-77.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue