Parliamentary election in Finland, 2 April 2023

Tapio Raunio

Professor at Tampere UniversityIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Tapio Raunio

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

The parliamentary elections that took place in Finland on 2 April, 2023 were in many respects unusual. Putin’s war in Ukraine has had a dramatic impact on Finnish security policy, with Finland seeking NATO membership by mid-May 2022 and joining the defence alliance two days after the election on 4 April. NATO membership was accepted almost unanimously in the Eduskunta, the unicameral national legislature, and hence the dramatic change in the country’s security policy status hardly featured at all in the parliamentary elections. However, a few security and defence policy experts with strong media presence were elected to the parliament from the ranks of the National Coalition (conservatives).

The second deviation from normal patterns concerned pre-election promises. In Finland, it has been customary for parties and their leaders not to commit themselves to any potential coalitions. Parties also tend to avoid declaring that they would not join any government involving a specific party (Raunio 2021). However, the situation had already changed in the previous elections held in 2019. Following the hardliner ‘coup’ within the Finns Party and the election of Jussi Halla-aho, the unofficial leader of the party’s anti-immigration wing, as the party chair in 2017, some parties indicated that it would be very difficult if not impossible for them to join a government that also included the Halla-aho-led Finns (Raunio 2019). Citing differences in worldviews, the three left-wing parties – the Social Democrats, the Green League, and the Left Alliance – announced that they would not share power with the Finns Party. The Swedish People’s Party also made it clear that it would be difficult for the party to enter a cabinet together with the Finns. Interestingly, the Finns Party started out as a populist, Eurosceptic party that was quite centrist and even centre-left on the socio-economic dimension, but has since the 2010s moved into a more right-wing direction, making opposition to immigration the central item on its agenda (Poyet & Raunio 2021).

The third unusual pattern was the extremely high popularity and visibility of Prime Minister Sanna Marin, the leader of the Social Democrats. Marin, currently 37, has been touted as the ‘rock star’ of Finnish politics, and she is clearly the most famous Finnish politician of the 21st century. Marin and her left-leaning five-party government that brought together the Social Democrats, the Centre Party, the Green League, the Left Alliance, and the Swedish People’s Party – all of which are parties chaired by women – received extensive international media coverage. Marin is also a polarizing figure, but her support has remained very strong throughout the early 2020s. Her popularity is also a major challenge for the Social Democrats, as Marin was probably a key factor in attracting younger and female voters to supporting the party. Three days after the elections, Marin announced that she would step down as the party chair in the party congress in September. Her successor, Antti Lindtman, will face a very tough job in ensuring that these voters continue to vote for the Social Democrats. Historically, SDP party members have belonged primarily to older age groups, while the two other leftist parties, the Greens and the Left Alliance, have been more popular among younger voters.

Marin’s government had steered the country through the Covid-19 pandemic and the first year of the war in Ukraine, but Finland had to incur further debt in the process. The centre-right parties, and particularly the National Coalition led by Petteri Orpo, therefore focused their campaigns on getting the economy back on track. As a result, while in 2019 climate change and socio-cultural issues had featured prominently in the campaign (Borg et al. 2020; Raunio 2019), the 2023 election was much more centered on economic issues (Arter 2023). Orpo proposed a ‘6+3’ policy, meaning that the next government should reduce debt by six billion euros and the government after that by three billion euros. The Finns Party and the Centre Party broadly agreed with Orpo, while the leftist parties argued against radical cuts and favoured investments that would generate growth and employment. The National Coalition is internally split on the socio-cultural dimension, and hence the focus on the economy worked in the party’s favour.

Marin’s government had finally managed to agree on a reform of social and health services, a topic that had been on the agenda of several previous governments. As part of that package, Finland established directly-elected regional councils (officially titled the councils of wellbeing services counties), with the first regional elections being held in January 2022 (Sipinen 2022). The funding and quality of social and health services has raised serious concerns, but it was harder to detect major differences between the parties, although the left-wing parties more systematically underlined the role of the state in providing such services.

Segregation among schools and students as well as internal security were two other major issues featured in the campaign. The Finns Party linked these to immigration. However, despite increasing reports about problems in the educational system and worsening street violence in the months leading to the elections, the election debates still focused to a large extent on state finances and the future of social and health services. In that respect, the campaign almost appeared as a throwback to the 1980s – the European Union or international politics were rarely mentioned, and socio-cultural issues, including climate change, remained in the background.

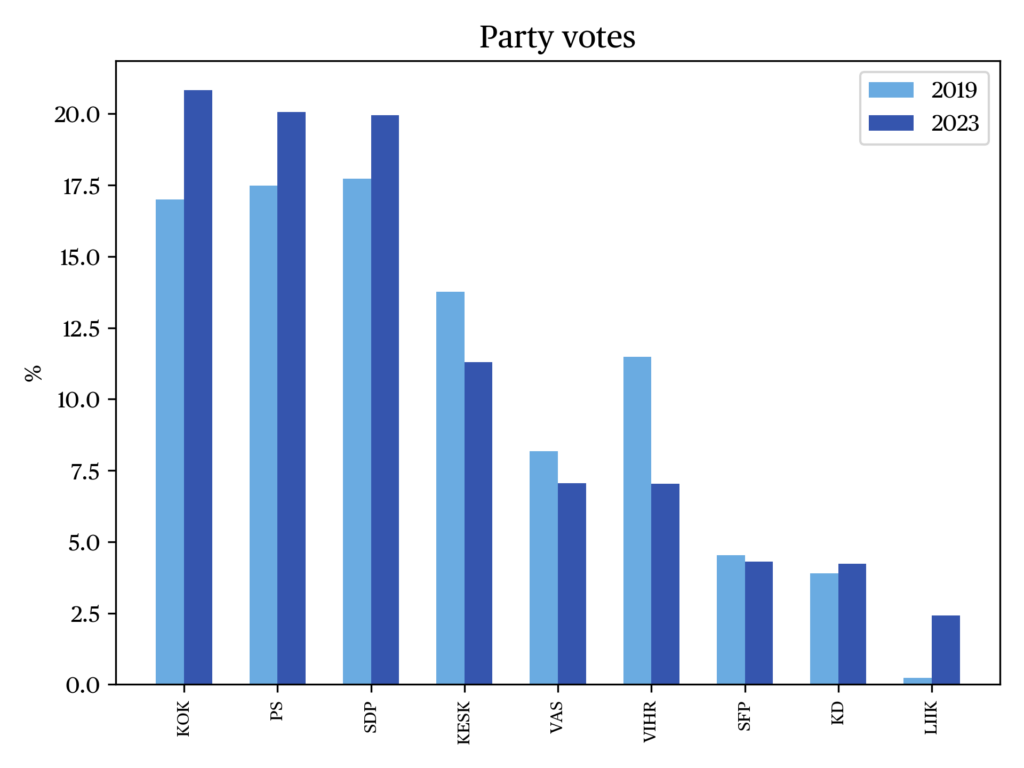

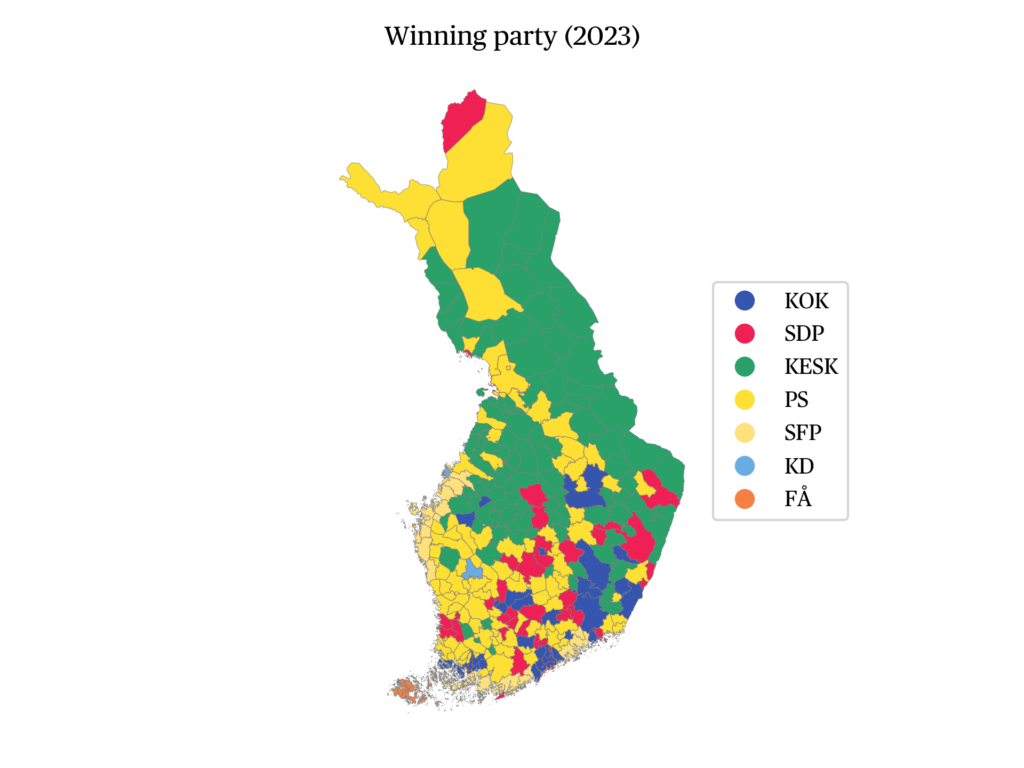

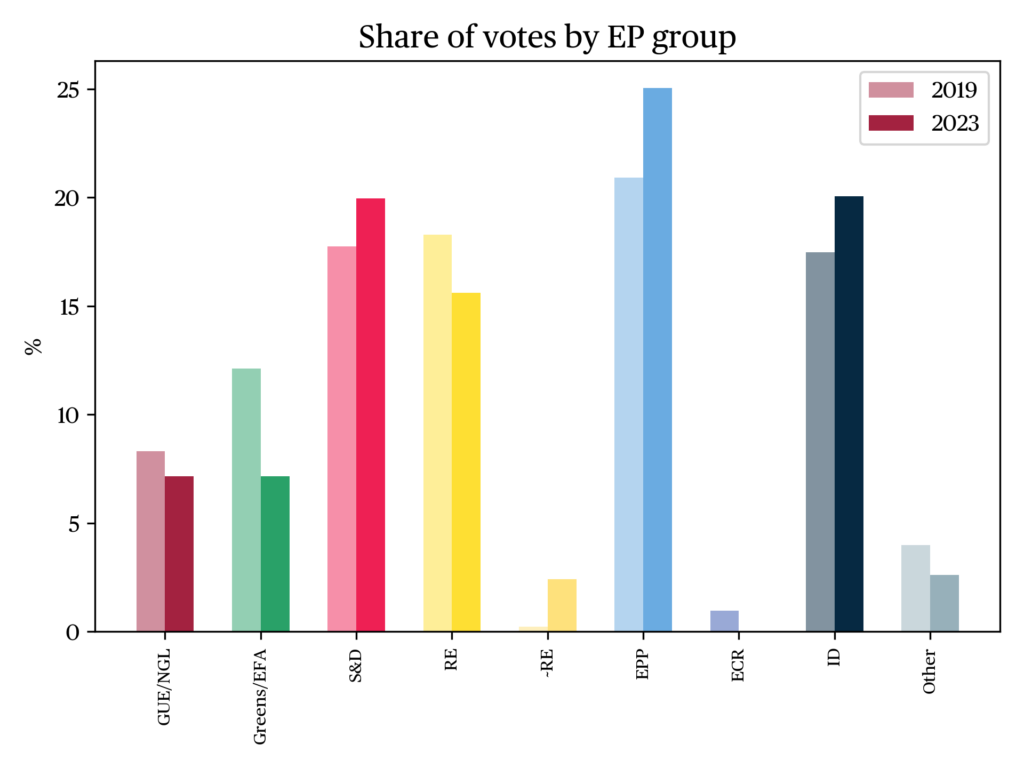

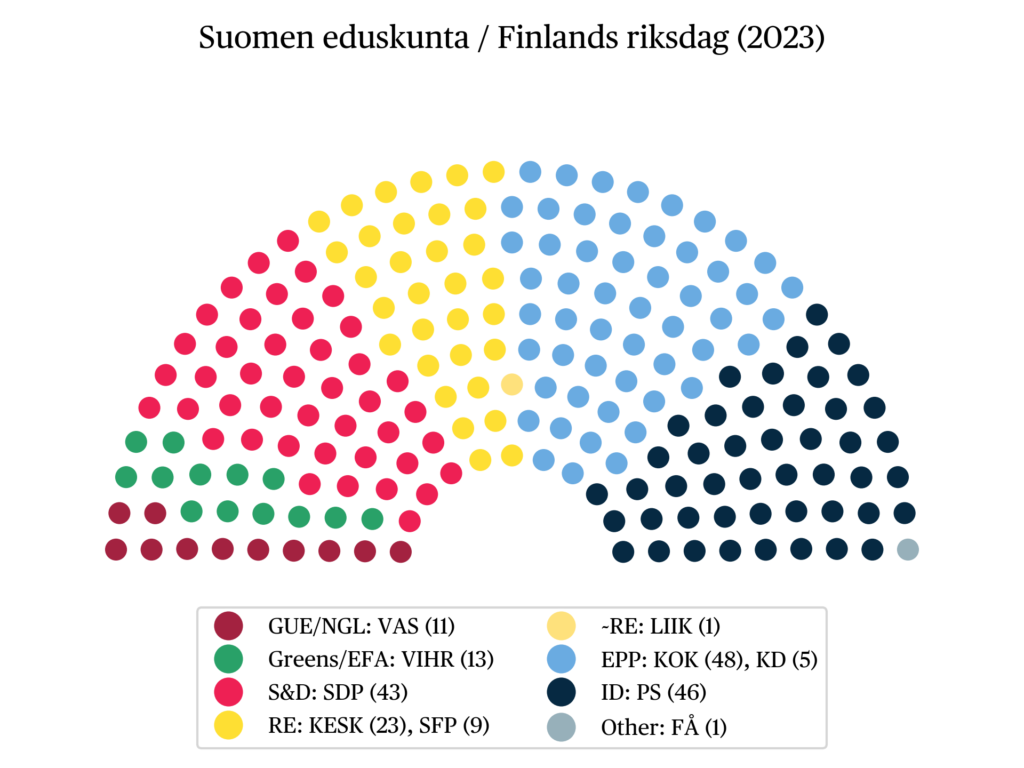

The results

The voters’ verdict was clear: Finland turned right (Grönlund & Strandberg 2023). Orpo guided the National Coalition to pole position, with 20.8% of the vote (+3.8) and 48 seats (+10). The Finns Party finished second with 20.1% of the vote (+2.6) and 46 MPs (+7). The populists achieved a breakthrough in the 2011 elections and have since then ranked among the three largest parties in all parliamentary elections. Most notably, in 2023 the Finns Party won votes throughout the country, in urban centres as well as in rural areas. Party leader Riikka Purra was the most successful individual candidate overall, with 42,594 votes in the Uusimaa district (the largest constituency). Since the 2011 elections, the Finns Party has been the largest party among working-class voters (when measured by occupation), yet the party remains critical of trade unions that continue to see the Social Democrats as their natural ally (Tiihonen 2022).

The Social Democrats came third with 19.9% of the vote (+2.2) and 43 seats (+3), an impressive result when considering that the party of the prime minister normally loses votes. There have been several coalition governments between the National Coalition and the Social Democrats since the late 1980s, but the two parties disagreed strongly on economic policy issues. During the campaign, Marin engaged in aggressive rhetoric against the National Coalition and the other parties of the right. Specifically, she argued that voting for the Social Democrats is the only way to prevent a victory of the political right. This did not go down well among the Green League and the Left Alliance, as the final campaign weeks eventually focused on who would finish first and therefore take the lead to form the new government – the National Coalition, the Finns Party, or the Social Democrats. The other parties received much less media attention, and the Greens found it particularly difficult to get their message across.

The Social Democrats gained votes from the other left-wing parties. In Helsinki district, the Social Democrats increased their support by 7.3% to 20.9%, while the Greens experienced an even larger drop. Party leaders Maria Ohisalo (Greens) and Li Andersson (Left Alliance) had to face severe electoral losses. The Greens only won 7% of the vote (-4.5) and 13 seats (−7), while the Left Alliance received 7.1% of the vote (-1.1) and 11 seats (-5). Roughly one-fourth of those who voted for the Greens and almost one-fifth of the Left Alliance voters in the 2019 elections switched to the Social Democrats (Kestilä-Kekkonen & Sipinen 2023). Tactical voting therefore benefited the Social Democrats, but it is nonetheless safe to predict that the support of the Greens will increase again over the next few years – and that this may happen at the expense of the Social Democrats. In June, the Green League elected a new leader, Sofia Virta, who has indicated that her party needs to focus more on economic policy instead of traditional ‘green’ issues.

The elections were a crushing blow for the Centre Party, which had led governments from 2003 to 2011 and from 2015 to 2019. The party, which had already suffered a humiliating defeat in the 2019 election, fared even worse this time, winning only 11.3% (-2.5) and 23 seats (−8). The Finns Party is now the biggest in several rural constituencies previously dominated by the Centre. It is likely that many Centre voters did not appreciate their party’s inclusion in the Marin cabinet from 2019 to 2023 – neither did they seem to have appreciated the ‘economy-first’ approach of the Centre-led cabinet in 2015-2019.

Among the smaller parties, the Swedish People’s Party won 4.3% (-0.2) and retained its 10 seats (including the representative of the Åland Islands). The Christian Democrats won 4.2% of the vote (+0.3) and held on to their five seats. Movement Now, registered as a party in late 2019, won 2.4% of the vote and maintained its sole MP. Turnout was 72%, a level at which turnout seems to have stabilized in the elections held in the 21st century.

Divisive times ahead

Marin and her cabinet received wide international media coverage. So has the new Finnish government, although for entirely different reasons. After the election, Orpo essentially had two options – either forming a right-wing cabinet that includes the Finns Party or going for the more traditional model of a blue-red coalition built around the National Coalition and the Social Democrats. Orpo went for the former, presumably because it assumed that it would enable the National Coalition to push through its economic reforms, including large cuts to public sector funding and weakening the influence of trade unions. The Christian Democrats and the Swedish People’s Party joined the coalition talks that lasted six and a half weeks, involved over one thousand expert hearings, and resulted in a massive, 216-page (excluding appendices) government programme (Finnish Government 2023). The coalition negotiations were full of drama, not least because of the obvious discomfort inside the Swedish People’s Party. After all, the Finns Party and the Swedish People’s Party have strong disagreements on socio-cultural issues, and the Finns Party has even been critical of the status of the Swedish language in Finland.

The four-party coalition – bringing together the National Coalition, the Finns Party, the Swedish People’s Party, and the Christian Democrats under the leadership of Prime Minister Orpo – was sworn into office on 20 June. It took only a week before the first crisis arrived. The Minister for Economic Affairs Vilhelm Junnila (Finns Party) announced his resignation on 30 June after a scandal over his far-right connections that led the Swedish People’s Party to support a no confidence motion in parliament. Junnila had joked about his election number (88) referencing “Heil Hitler“, had spoken at a far-right event in 2019, and had tabled a parliamentary question in which he urged the government to promote abortion in Africa which he claimed was a measure to stem population growth and fight climate change (Yle 2023c). A couple of weeks later attention turned to Purra, the new Minister of Finance. Back in 2008 she had repeatedly used racist language in texts on the Scripta blog hosted by Halla-aho. For example, she had written about a confrontation on a train with young people from an immigrant background, saying “If they gave me a gun, there’d be bodies on a commuter train too, you see” (Yle 2023e). Purre had also written derogatory comments about Muslim women in 2019 (Yle 2023d). In late July the scandal deepened as Helsingin Sanomat, the leading national daily, published messages containing racist slurs and language sent by Minister of Economic Affairs Wille Rydman from the Finns Party to his previous partner (Yle 2023b). The messages were from 2016, when Rydman was still a member of the National Coalition.

Purra regretted these blog texts, but doubts linger about how genuine her apologies are. Overall, the Finns Party has accused the mainstream media of running an intentional smear campaign against the party, with old texts dug up purposefully to force the government to resign. Orpo meanwhile stayed mainly quiet, defending his cabinet and asking the media and the public to focus on actual policy questions and to let the government do its job. However, anxieties within the Swedish People’s Party have not faded away, while the liberals inside the National Coalition also feel uneasy about the situation. Halla-aho, who was elected as the Speaker of Eduskunta, decided not to reconvene the parliament during the summer break to debate the fate of Purra and the government (Yle 2023f), and much of the public outcry about racism had dissipated by early September when the whole government, Purra, and Rydman survived separate votes of confidence in the Eduskunta (Yle 2023a).

Arter (2023) has called the coalition an ‘unhappy marriage’, and even Orpo has referred to it as a ‘marriage of convenience’. It may well be that the coalition will not last until the next parliamentary elections scheduled for Spring 2027. Even if it does, the next parliamentary term will be a tumultuous ride: in addition to the racism scandals, the implementation of the ambitious government programme is guaranteed to raise concerns both inside the coalition and in society as a whole. Already in September and early October there has been a range of anti-government activities from various types of industrial action to public demonstrations and sit-in protests at university campuses. At the same time the leadership of the Finns Party has become fiscally very conservative in recent years, and it may be that a ring-wing economic policy is the glue keeping the government together.

An interesting development concerns the prospect of bloc politics and increasing polarization between opposing camps (Kekkonen 2023). The pre-electoral promises made by the left-wing parties of not sharing power with the Finns Party – and the willingness of the centre-right parties to do so – resulted in debates about polarization and the growing distance between the right and the left during the campaign. These debates will no doubt continue as the policies of the Orpo government are controversial among Finnish citizens. As Finland is known for its tradition of broad, mainly cross-bloc coalitions, a move towards bloc politics would constitute a significant departure from established practices. One thing is clear: Finnish politics will no longer be boring.

The Data

References

Arter, D. (2023). The making of an ‘unhappy marriage’? The 2023 Finnish general election. West European Politics.

Borg, S., Kestilä-Kekkonen, E., & Wass, H. (eds.) (2020). Politiikan ilmastonmuutos: eduskuntavaalitutkimus 2019. Oikeusministeriön selvityksiä ja ohjeita 2020:5. Helsinki: Oikeusministeriö.

Finnish Government (2023). A strong and committed Finland. Programme of Prime Minister Petteri Orpo’s Government, 20 June 2023. Helsinki: Publications of the Finnish Government 2023:60.

Grönlund, K. & Strandberg, K. (eds.) (2023). Finland turned right: Voting and public opinion in the parliamentary election of 2023. Åbo: Samforsk, The Social Science Research Institute, Åbo Akademi University.

Kekkonen, A. (2023). Affective polarization in a multiparty democracy: Learning from the case of Finland. Doctoral dissertation, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Helsinki.

Kestilä-Kekkonen, E. et Sipinen, J. (2023). Taktinen äänestäminen. Vaalivälähdykset 2023:10, Vaalitutkimuskonsortio (FNES).

Poyet, C. & Raunio, T. (2021). Confrontational but Respecting the Rules: The Minor Impact of the Finns Party on Legislative–Executive Relations. Parliamentary Affairs 74:4, 819-834.

Raunio, T. (2019). The Campaign. Scandinavian Political Studies 42:3-4, 175-181.

Raunio, T. (2021). Finland: Forming and Managing Ideologically Heterogeneous Oversized Coalitions. In Bergman, T., Bäck, H., & Hellström, J. (eds), Coalition Governance in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 165-205.

Sipinen, J. (2022). Regional elections in Finland, 23 January 2022. Electoral Bulletins of the European Union, 3.

Tiihonen, A. (2022). The Mechanisms of Class-Party Ties among the Finnish Working-Class Voters in the 21st Century. Doctoral thesis, Tampere University.

Yle (2023a, 8 September). Finland’s right-wing government, 2 ministers survive confidence votes. Yle.

Yle (2023b, 28 July). HS publishes racist messages by Economic Affairs Minister Rydman. Yle.

Yle (2023c, 30 June). Junnila resigns after week-long row over far-right links. Yle.

Yle (2023d, 20 July). Muslim groups condemn Riikka Purra’s “black sacks” blog comment. Yle.

Yle (2023e, 11 July). Riikka Purra “not resigning” as controversial blog comments resurface. Yle.

Yle (2023f, 15 July). Speaker Halla-aho decides not to reconvene Parliament over Purra comments. Yle.

citer l'article

Tapio Raunio, Parliamentary election in Finland, 2 April 2023, Nov 2023,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue