Parliamentary election in Portugal, 30 January 2022

Marco Lisi

Marco Lisi is an Associate Professor at NOVA University LisbonIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Marco Lisi

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

Background

The Portuguese party system has been named an “island of stability” in the European political landscape, as it did not suffer any electoral earthquake or major reconfiguration of party competition in recent years. This was remarkable given the deep transformation of party systems experienced by Southern European countries hit by the Great Recession.

1

The two mainstream parties — the centre-left Socialist Party (PS) and the centre-right Social Democratic Party (PSD) — have been able to retain widespread support and maintain a pivotal role in government formation, while no new populist party made a major breakthrough in the electoral arena.

Despite this apparent stability, however, a process of dealignment has fostered incremental changes in the party system, evidenced by growing rates of abstention and increasing levels of party fragmentation. New parliamentary forces also emerged. The first was the green party PAN (People-Animals-Nature party), which was able to obtain one MP in the 2015 elections. In the following election (2019), three new actors emerged. On the left side of the political spectrum, the left-libertarian Livre obtained one representative. The party defends pro-European stances and an ecologist agenda, and puts a strong emphasis on digital innovation. On the right side, the liberals (Iniciativa Liberal, IL) and the populist right-wing party Chega (‘Enough’, CH) also gained representation for the first time, although with different programmatic stances and strategies.

While the reconfiguration of the right followed some of the trajectories already experienced by most European countries in the past decades, party system innovation on the left was triggered by an unprecedent cooperation between left-wing parties. After the 2015 election, a new government formula emerged, when the PS signed an agreement with the radical left (composed of the Communist Party [PCP], the Left Bloc [BE] and the Greens [PEV]), which included the reversal of some policies implemented during the Troika years.

2

Despite divergence on fundamental issues — e.g., labour policies, pro vs. anti-European stances, etc. —, this cooperation (dubbed the “Contraption”, pt. Geringonça) allowed the PS minority government to govern to the end of its four-year mandate.

3

This important shift marked a watershed in Portuguese politics and had important transnational consequences, as it demonstrated that moderate left-wing parties can cooperate with more radical allies, a path followed in the following years in Spain. While coalitions between right-wing parties have been frequent throughout the democratic regime, this innovation contributed to reduce the disadvantage suffered by left-wing parties in the government formation process.

Despite this important experience, the left-wing parties decided not to renew their government agreement after the 2019 elections, in which the PS won a plurality of the vote but did not achieve an overall parliamentary majority. This time, the Socialists did not pursue their cooperation with the radical left, instead choosing to govern alone and to negotiate policy proposals one by one with opposition parties. Only a few months after being formed, the new government had to face the Covid-19 emergency, and was in charge of implementing the policies needed to address the associated public health and economic issues. During the pandemic, the PS could benefit from the support of a number of opposition parties which toned down political conflictuality in an effort to deal with the public health emergency and to avoid unnecessary social tensions. Most of the time, the PSD proved cooperative, while the radical left gradually distanced itself from the Socialist executive. By the end of 2021, strategic motivations determined the end of this unstable arrangement. On the one hand, both radical-left parties were losing electoral support, and this was particularly evident for the PCP, which had lost some major strongholds in the local elections held in October 2021. On the other, the PS was confident that a snap election could strengthen its position vis-à-vis opposition parties, given not only the difficulties experienced by the radical left, but also the weakness of right-wing parties, which were not able to influence the political agenda and to avoid internal conflicts. The pandemic context was also especially important as it boosted the PS’s confidence in its ability to win an early election. In fact, during its initial stages, low levels of political polarization, a climate of cross-party collaboration and the support of the President of the Republic facilitated the control of the pandemic.

The campaign

The election took place after the collapse of António Costa’s minority government, which followed the Parliament’s failure to approve the state budget for 2022. In view of the unwillingness of the main parties to form a new parliamentary majority, the President of the Republic Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa, who had himself been re-elected for a second mandate in January 2021, called for early elections

The election campaign was characterized by three main aspects. The first was the pandemic, as the country was in a declared state of calamity. This limited grassroots mobilization and increased the importance of television debates among party leaders as well as the use of new digital tools and platforms. Notably, Portugal experienced a peak of the coronavirus in the month preceding election day. The government facilitated advance voting, an option used by more than 300,000 voters. Despite this, many political observers feared the circumstances could demobilize voters, especially among older cohorts. As political parties limited the organization of rallies or mass events, TV debates among party leaders assumed a key role in the campaign. The televised debate between PS leader Costa and PSD leader Rio played a particularly important role, reaching the highest audience figures with more than three million viewers. The pandemic also shaped the media agenda and health issues have been one of the most debated topics. Yet the way the socialist government dealt with this situation was not storngly politicized and very few policy proposals were directed at the effects of Covid-19, with the exception of mental health. This could explain the electorate’s positive perceptions of the government’s management of the health and social crises.

The second major aspect was the unprecedent fragmentation of the political system and the role played by new leaders and parties. Minor parties were able to set the campaign agenda by politicizing new policy issues and focusing attention on social media. While IL appealed to young people and upper social classes by stressing liberal policies, Chega was effective in mobilizing its electorate around an anti-elite populist narrative. Livre emphasized the importance of digital transition and the fight against climate change. However, the health emergency continued to consume much political attention during the campaign, and this was to the advantage of PS, which was perceived to have handled it competently.

Another aspect that dominated the campaign was the debate around political stability and the high competitiveness of the elections, with the PSD showing — according to opinion polls — an increasing capacity to gain support and challenge the predominant position of the PS. Indeed, one week before the election, several polls suggested a technical tie between PS and PSD, neither of which seemed able to obtain an overall parliamentary majority (with both parties gathering around 35% of the vote). However, the polls published during the campaign made it clear that the PS was going to win the election, although probably without an overall parliamentary majority.

From this viewpoint, the campaign was also fought on post-electoral scenarios. The PS started seeking an absolute majority to avoid having to deal with a hung parliament after the election. Opposition parties argued that an absolute majority was not desirable as it could endanger democratic equilibria. As the polls made this scenario less and less realistic and a potential victory of the right against the left was not to be excluded, another topic entered in the campaign, namely post-electoral agreements. Many observers considered an agreement between the PS and PSD as a probable outcome, which would have resulted in a kind of grand-coalition government. This solution was backed up by many economic interest groups, especially due to the management of the European recovery program. On the other hand, left-wing parties talked about a potential alliance between PSD and CH as a threat for democracy. Indeed, one of the main weaknesses of the PSD leadership was the ambiguity of its strategy of alliances. Rio did not firmly reject the possibility of cooperation with the radical right party, and at the same time he claimed to be willing to facilitate the survival of a socialist government in case the PS would win a plurality, but no majority of seats in parliament.

4

The results

Voter turnout (51.4%) registered a slight increase compared to previous elections. This is quite remarkable not only because of the long-term trend towards demobilization that affected Portuguese elections, but also because of the constraints associated to the pandemic. Moreover, the fact that this was a snap election was also expected to negatively affect voter participation. The turnout increase was probably due to the competitiveness showed by the polls and the mobilization fostered by new parties.

5

But organizational aspects of the election also played an important role in fostering mobilization. For instance, alternative voting options have been made available, such as early and mobile voting. Additionally, the government decision (although controversial as it was made very close to election day) to allow voters in self-isolation to vote in person can also explain the high turnout levels.

The results of the 2022 legislative elections were quite surprising in light of the opinion polls published during the campaign. Few of them predicted the possibility of an overall parliamentary majority for the PS; even more striking was the low score achieved by the PSD. Instead, opinion polls indicated a convergence between the two main competitors, with a clear upward trend of the PSD since December 2021. Meanwhile, many political observers and journalists tried to interpret the failure of opinion polls to predict the final results. The fear of a potential loss of a leftist majority certainly led many left-wing voters to vote strategically and to concentrate their vote on the PS. However, there may be other causes for this phenomenon, such as asymmetrical mobilization or the high proportion of undecided voters and abstentionists. In any case, this was quite exceptional in the Portuguese context as opinion polls for legislative elections have not traditionally failed to predict election outcomes.

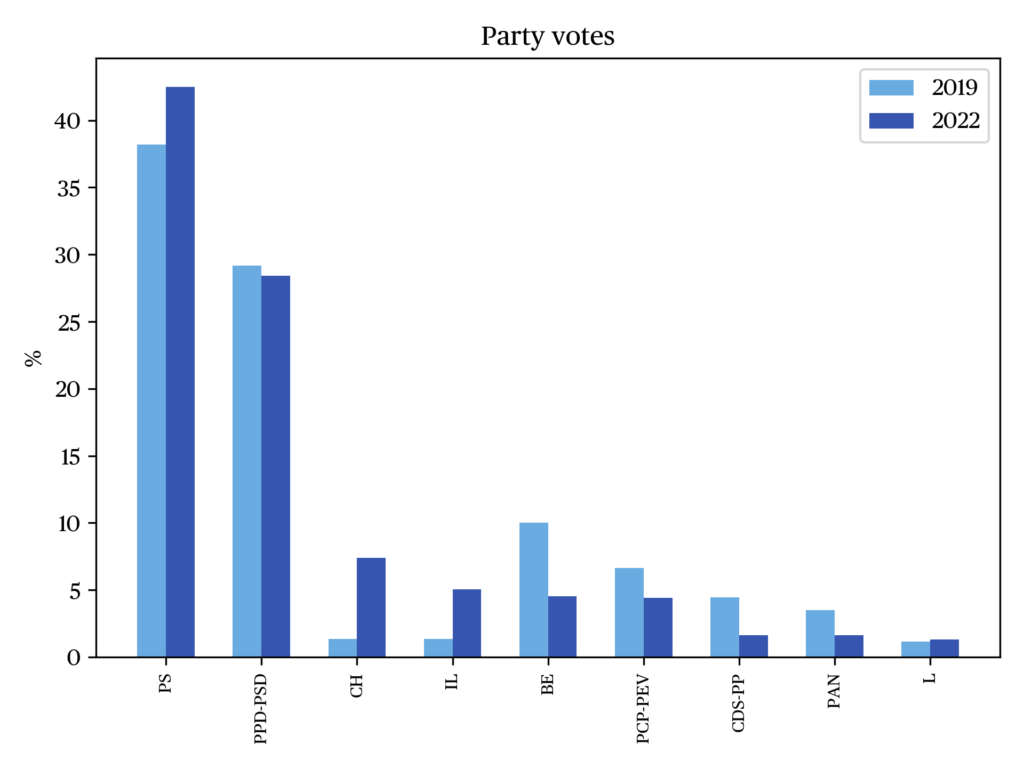

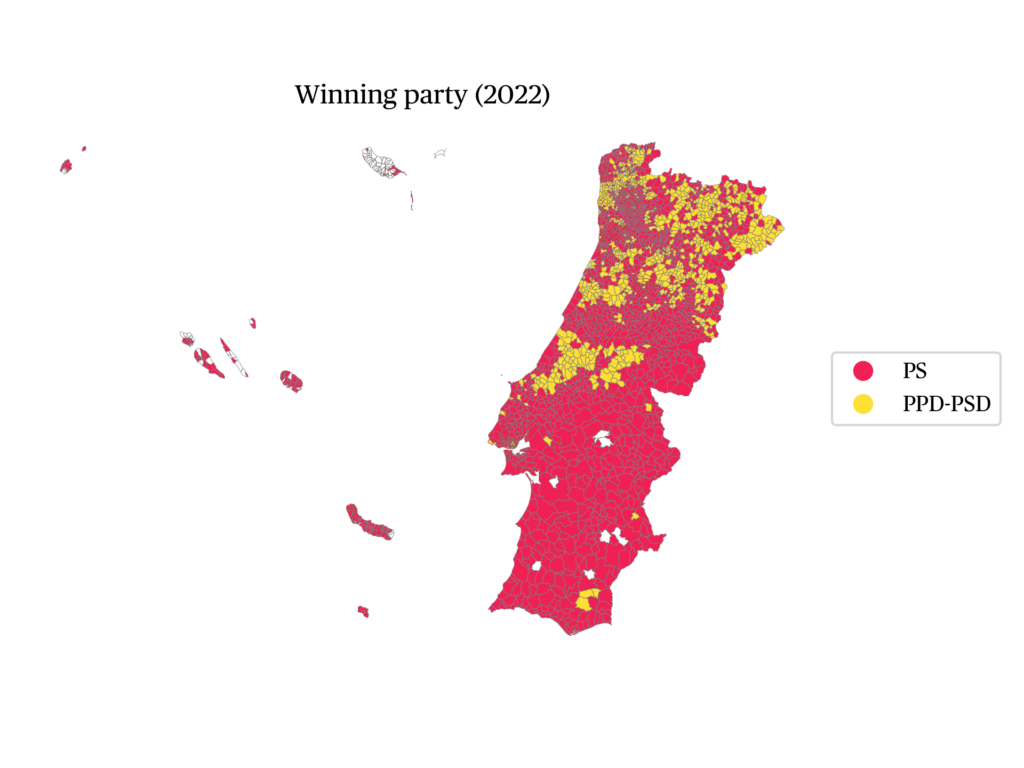

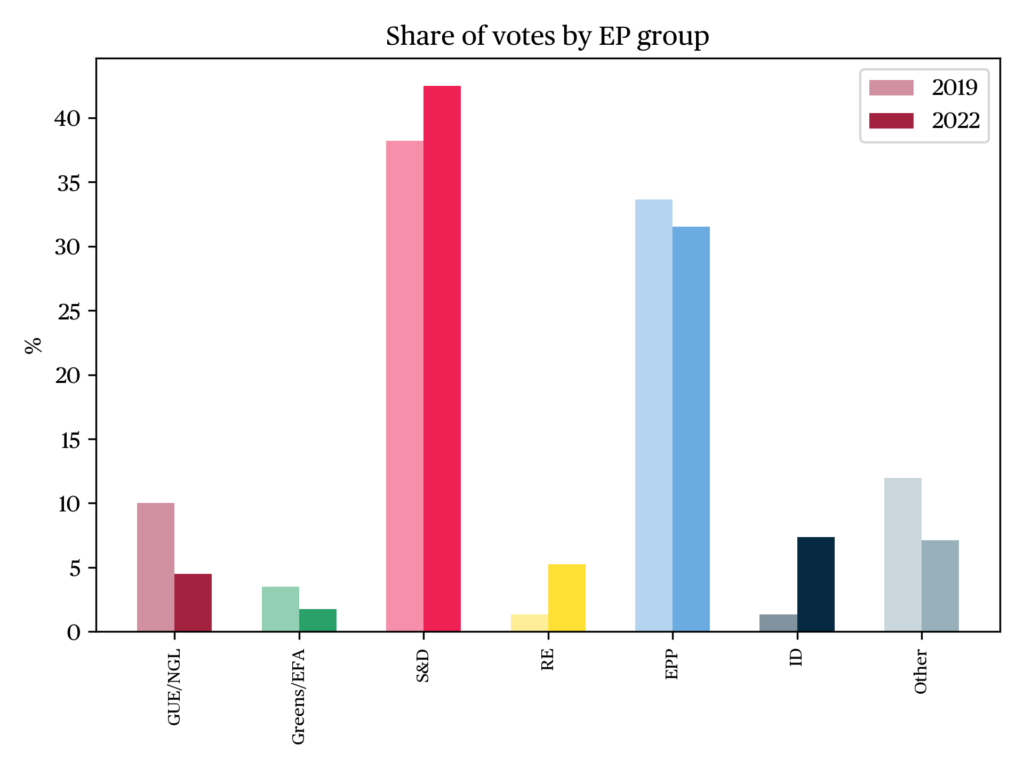

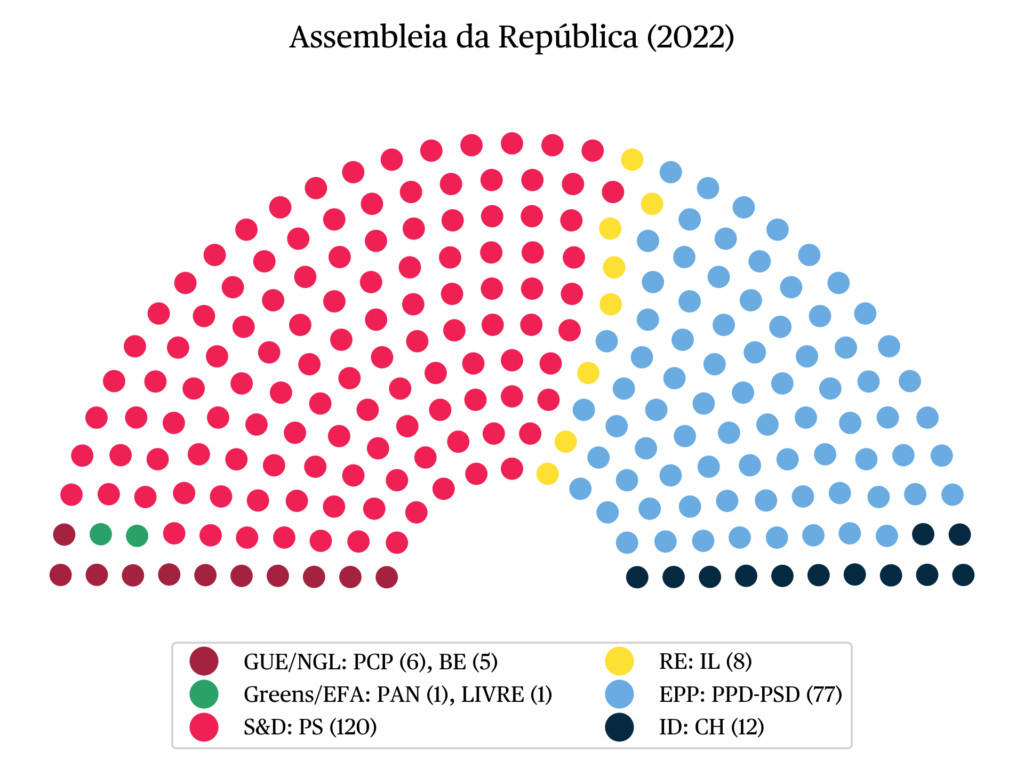

The results of the 2022 elections were also quite exceptional because of the absolute majority achieved by the PS. This is a historical achievement, as the socialists only obtained a similar result in 2005, and not an easy one given the proportionality of the electoral system and the distribution of the socialist vote in the territory, which is quite dispersed and homogeneous. The PS’s score of 41.4% was its second-best result ever in a legislative election and a significant breakthrough compared to previous elections, with a more than 5-percentage-point increase. By contrast, the PSD only obtained 29% of the votes, remaining at the same level as in the 2019 election. This was the second defeat of Rui Rio in legislative elections, and the party lost important strongholds, especially in the Northern part of the country.

The surprise also came for the score achieved by minor parties. The populist radical right Chega came third, with a score of 7.2% and 12 MPs. Liberal Initiative also performed well, obtaining 4.9% of the votes. Overall, both forces were able to substantially increase their vote shares compared to previous elections, strengthening their parliamentary representation. Chega’s resounding success was based, first of all, on protest and ideologically radical voters, most of whom came from the CDS. Populist attitudes may hence be key in explaining Chega’s electoral breakthrough. The new party was also disproportionately supported by male voters. On the other hand, IL presents a very different support base, mostly concentrated on younger and educated people. Territorial support also shows distinct patterns for the parties. While CH displayed higher levels of penetration in the interior (as the distance from the capital increases), IL is more popular in urban constituencies.

All other parties suffered a heavy defeat. Both radical left parties (BE and PCP) lost a significant proportion of votes and parliamentary seats and, even more importantly, they were bypassed by newcomers. The result for the BE speaks for itself, with a decrease in parliamentary representation from 19 to just 5 seats (from 9.5% to 4.4% in terms of votes). The CDU was not able to halt this declining trend, and suffered a substantial decrease in both its percentage (4.3%) and absolute number of votes compared to previous elections. In addition, for the first time since 1983, its coalition ally (PEV) was not able to elect any MP. Radical left parties were attacked during the campaign for bearing the main responsibility for the political instability created by the lack of approval of the budget proposal. In addition, it was not clear to the leftist electorate why, despite traditional programmatic differences, they were not able to cooperate with the socialists as during the “Geringonça”. Finally, PAN also lost votes and MPs (from 4 to 1), while Livre was able to secure one MP, as in the previous elections.

The defeat was felt even more strongly in the case of the CDS (a conservative, right-wing party), which was not able to send any representative to the parliament. This was a historical result, as the CDS was one of the founding parties of Portuguese democracy and it was always able to elect MPs in every parliamentary election. Despite its attempt to compete with Chega, the lack of leadership appeal, internal conflicts and the failure to promote programmatic renewal led the party to a dramatic defeat.

The PS obtained an overall parliamentary majority mainly due to the ‘punishment’ inflicted by voters on radical parties, which were held responsible for triggering an undesired political crisis, as well as the lack of credibility of the PSD, which was not able to capitalize on the weakening of the socialist government. The management of the government with regard to the public health emergency and economic recovery also helped the PS consolidate its position vis-à-vis opposition parties. Indeed, it is important to underscore that Portugal has been praised by international organizations regarding the management of the pandemic and of the vaccination campaign. Although post-election surveys are not available yet, looking at the aggregate level it is plausible that the PS attracted voters not only from the radical left, but also from the PSD and abstentionists.

Conclusions

Government formation took more time than expected due to illegal procedures registered in out-of-country constituencies. This led the national electoral administration to repeat elections in these electoral districts on 12 and 13 of March. After the confirmation of the seat allocation for out-of-country constituencies, the new executive took office. The new cabinet showed a significant centralization of powers in the Prime-Minister’s hands; António Costa appointed some members of his coterie in key cabinet positions, and also directly controlled EU affairs and the digital transition portfolio. The fact that, during this mandate, the government will manage the financial package of the Recovery and Resilience Plan seems to have played a key role in António Costa’s decision to centralize and politicize the executive in comparison to the previous mandate. Finally, it is worth noting that this is the first parity government in Portuguese history, including women in traditionally male portfolios (for instance, Defense).

The 2022 legislative elections were significantly marked by the pandemic context, which had a multidimensional impact on this electoral process, not only in terms of campaign mobilization and agenda, but also by influencing the decision to call for early elections, as well as voting choices. Nonetheless, the outcome of these elections can perhaps be best understood as a reward to the moderate orientation of the PS and a fear of political instability and a potential radicalization of the political landscape. Portuguese voters punished the lack of cooperation between radical left parties and the PS government, but they also mistrusted a possible alliance of the PSD with Chega, which could have led to unpredictable policies. Overall, the political change these elections brought to the fore was more evident on the right than on the left side of the political spectrum, a pattern which follows (with some delay) the trajectory experienced by many European countries, as Portugal is a latecomer in terms of the rise and success of a new radical right populist party. It also exhibits a pattern of increasing fragmentation of party politics, which will make it more difficult to form stable governments in future elections. This trend is most visible on the right side of the political spectrum: new parties emerged as a consequence of the crisis experienced by the PSD (internal conflicts, lack of clear programmatic strategy, etc.) and its competition with the CDS. From this viewpoint, it is worth noting that the growing party system fragmentation does not reflect the emergence or politicization of new cleavages; rather, it is the effect of party strategies and the successful performance of political entrepreneurs.

The PS will enjoy a unique opportunity to implement the policies presented in its electoral manifesto during the next four years. The overall parliamentary majority provides the government the necessary stability to plan and execute key reforms, especially in the financial, economic and welfare sectors. The guidelines are quite clear and follow the path already taken during the previous governments. This means a cautious management of public finances, more investments in the health and education sectors and the reduction of inequalities. Decentralization is another key reform that the government aims to achieve during this mandate. How to foster economic development of the country remains the greatest challenge, together with the rise of inflation created by the Ukraine war. In the midst of an energy crisis and with the international situation still to be resolved, the task of the new government may not be easy.

References

De Giorgi, E. & Santana Pereira, J. (2020). The Exceptional Case of Post-Bailout Portugal: A Comparative Outlook, South European Society and Politics. South European Society & Politics 25(2): 127–50.

Fernandes, J. M., Magalhães, P. C., & Santana-Pereira, J. (2018). Portugal’s Leftist Government: From Sick Man to Poster Boy? South European Society and Politics 23(4): 503–24.

Lisi, M. (2016). U-Turn: The Portuguese Radical Left from Marginality to Government Support. South European Society & Politics 21(4): 541–60.

Lisi, M., Rodrigues Sanches, E., & dos Santos Maia, J. (2020). Party system renewal or business as usual? Continuity and change in post-bailout Portugal. South European Society and Politics 25(2): 179–203.

Notes

- See De Giorgi and Santana Pereira (2020).

- The communists (PCP) and the Greens (PEV) run together in the legislative election as the CDU (Unitary Democratic Coalition) coalition.

- See Lisi (2016); Fernandes et al. (2018).

- It is worth noting that in the autonomous region of Azores, the current government (2020-) is supported by a coalition between right-wing parties, namely PSD, CDS (Social Democratic Centre) and Chega. This was considered an important precedent and radical left parties used it as an example of the availability of the PSD leader to negotiate or cooperate with Chega in order to defeat left-wing parties.

- There is evidence that in the 2019 legislative elections new parties reported higher scores of the vote in districts with higher levels of turnout (see Lisi et al. 2020).

citer l'article

Marco Lisi, Parliamentary election in Portugal, 30 January 2022, Oct 2022,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue