Parliamentary Election in Rhineland-Palatinate, 14 March 2021

Marius Minas

Research Associate at the Chair for Western Government Systems at the University of TrierIssue

Issue #1Auteurs

Marius Minas

21x29,7cm - 102 pages Issue #1, September 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe: December 2020 — May 2021

Voting in 2021

On 14 March 2021, the so-called “super election year” kicked off in Germany. On that Sunday, the citizens of Rhineland-Palatinate and Baden-Württemberg elected their representatives in their respective state parliaments — Saxony-Anhalt, Berlin and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania will follow later in the year. Likewise, the election for the 20th German Bundestag will take place on 26 September 2021. These six different elections at the state and federal levels — plus local elections — are of great importance for the political landscape in Germany. Moreover, in the German multi-level system, elections influence each other (Jun et Cronqvist, 2020:305; Detterbeck et Renzsch, 2008 ; Burkhart, 2007). The elections in Rhineland-Palatinate and Baden-Württemberg could thus be seen not only as a chronological prelude, but also as an indicator of political trends in this “super election year.”

The Corona pandemic is a distinctive feature of 2021, which has affected the whole election process (Leininger et Wagner, 2021). On the one hand, from an organisational point of view, hygiene concepts and regulations for the polling stations have to be developed, implemented and supervised; additional postal votes need to be made available. On the other hand, the debate about the pandemic occupies a large part of the political discourse. The parties’ attitudes towards Covid policies add to — and sometimes even overshadow — the traditional content of election programmes. Representatives of the governing parties in the federal and state governments receive (even) more media scrutiny as the crisis management is managed in an increasingly executive manner.

Meanwhile, the traditional (analogue) election campaign on the ground is severely limited. The resulting unequal distribution of media presence of the candidates and their parties favors officeholders, whose visibility significantly increases — a non-negligible advantage in the election campaign. On a programmatic level, the population tends to place more trust in incumbent politicians in times of crisis, possibly because of a “rally-around-the-flag” effect. According to Mueller, this effect is particularly noticeable in the wake of global and dramatic events, which attract the public’s attention towards public officials (Leininger et Wagner, 2021 ; Mueller, 1970). This is undoubtedly the case with the Covid-19 pandemic.

The increased number of postal ballots also changes contextual factors as defined by the Michigan model frequently used in electoral research. Those without a stable party identification decide only shortly before election day for which party they will vote. Thus, news coverage in the preceding weeks strongly influence the voting decision. However, with postal votes, the period between submitting the ballot and the actual election day is barely, and sometimes not at all, reflected in the voting decision. This has been the case with this year’s “mask affair” involving CDU/CSU MPs in the Bundestag.

The results of the 2021 Rhineland-Palatinate state election in perspective

In 2021, 101 members of parliament were elected in 52 constituencies in Rhineland-Palatinate by means of personalised proportional representation. With a first vote, citizens elected a constituency MP in their respective constituencies using a first-past-the-post system. However, the exact number of MP seats won by each party is eventually determined in proportion to second vote results, with seats being distributed only among parties which have obtained at least five per cent of second votes (a system known as the “five per cent clause”). After deducting the seats that the parties are entitled to through winning constituencies (first vote), the remaining representatives are chosen from state or district lists submitted before the election. 1

Voter turnout in 2021 was 64.3% (2016: 70.4%), of which the proportion of postal voters represented almost two-thirds (2016: approx. 31%).

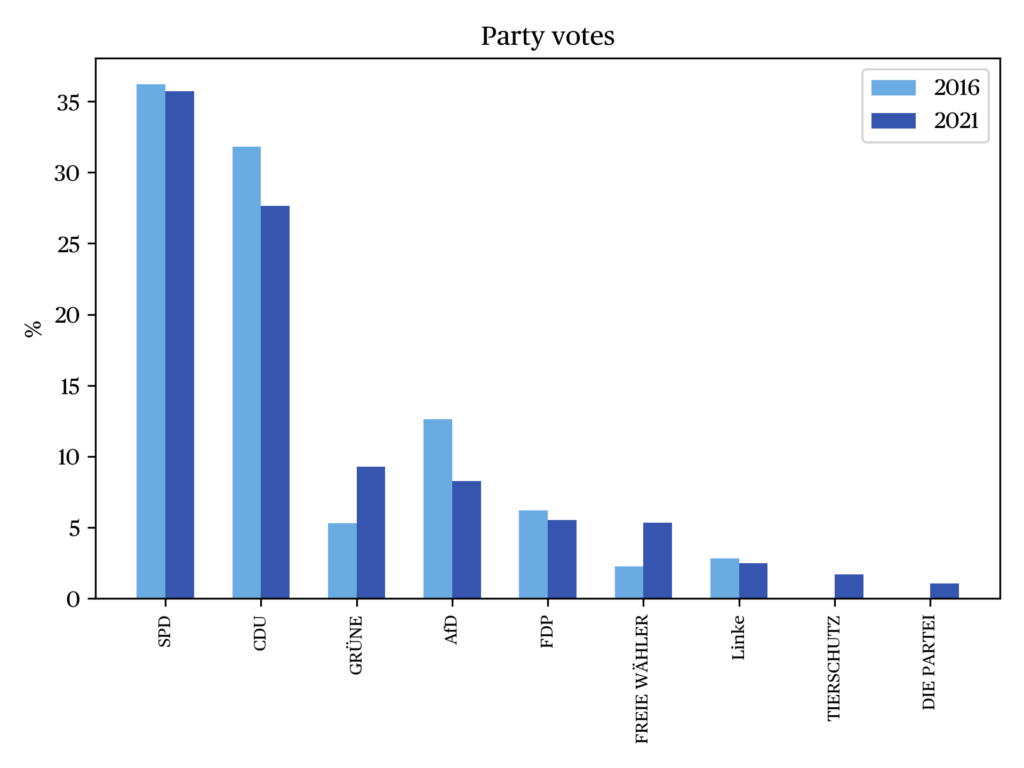

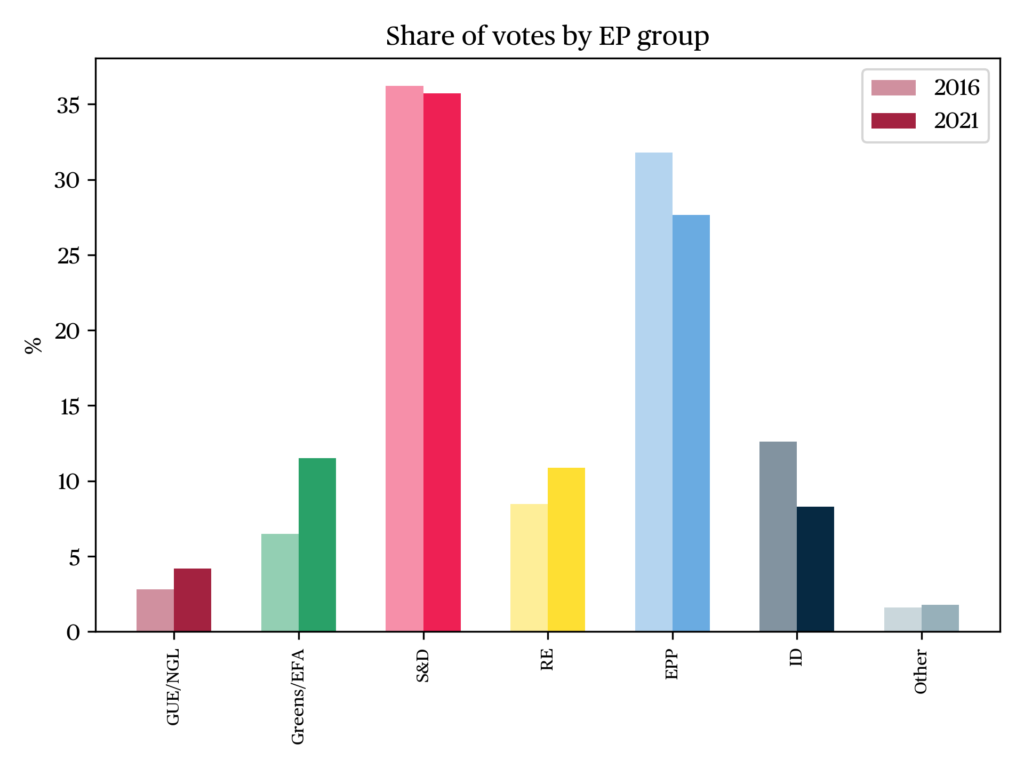

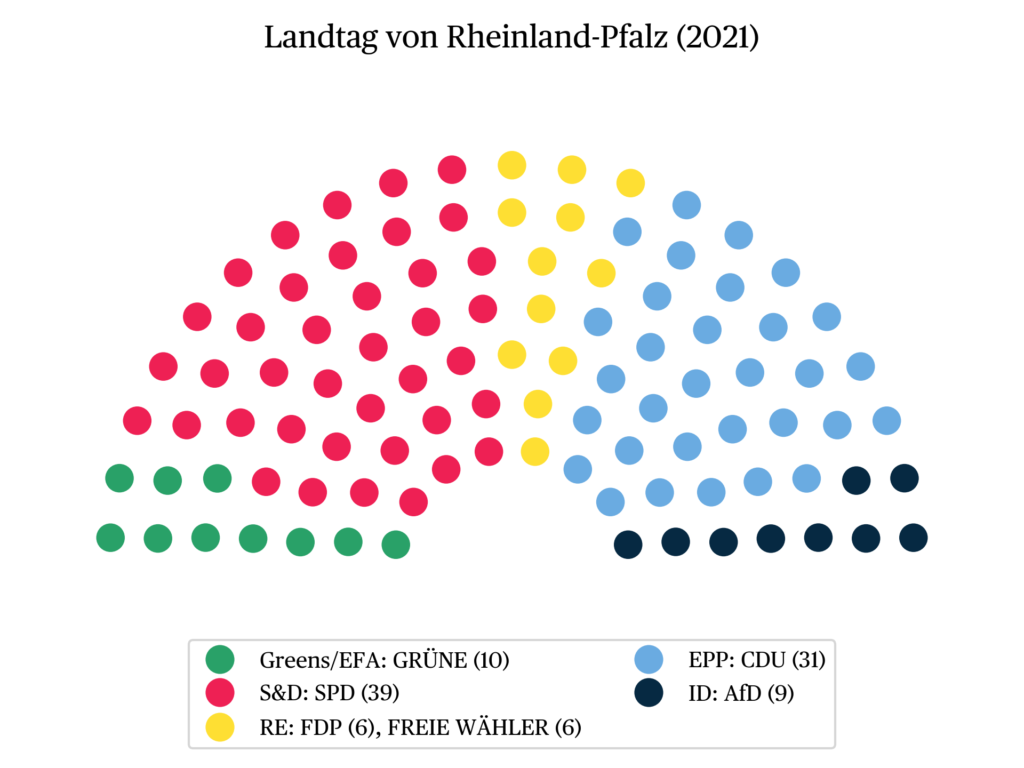

As can be seen in the graphics in the “data” panel, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD; S&D) emerged as the winner, contrary to the poll results in the months before the election. 2 With 35.7% of the state votes and 32.2% of the constituency votes, the party won 39 of the 101 seats, 28 of which were direct mandates. The Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU; EPP), which was just ahead of the SPD in the aforementioned pre-election polls, won 27.7% of the state votes and 31.4% of the constituency votes on election day — its worst result ever at a state election in Rhineland-Palatinate. The party obtained only 31 seats in the state parliament, 23 of which were direct mandates. Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (The Greens; Greens/EFA) become the third strongest force in parliament with 9.3% of the state vote, 10.9% of the constituency vote, and will thus have ten seats (one direct mandate). The Alternative for Germany (AfD; ID) won 8.3% of the state vote and 7.6% of the constituency vote, which amounts to nine seats in parliament. The third governing party (alongside the SPD and the Greens), the Free Democratic Party (FDP; RE), also re-enters parliament with six seats, having received 5.5% of the state vote and 6% of the constituency vote. The Free Voters Party (FW; RE) is a newcomer. Having received 5.4% of the state vote and 7.5% of the constituency vote, the party will have six seats in parliament. Finally, the Left Party (GUE/NGL) 3 , the Animal Welfare Party (Tierschutzpartei) 4 , The Party (Die Partei) 5 , Volt (Greens/EFA) 6 and other parties 7 failed to reach the five per cent threshold.

Compared to the 2016 state election, two of the six parties represented in the new state parliament improved their results in terms of state votes. The Greens increased their share by 4.0 and the Free Voters by 3.2 percentage points. The other four parties saw their share of the state vote decline. While the losses of the two remaining governing parties, SPD (-0.5%) and FDP (-0.7%), are comparatively small, the two opposition parties recorded heavier losses: CDU (-4.1%); AfD (-4.3%).

Explanatory factors according to the Michigan model

In 2020, Jun and Cronqvist described party competition on Rhineland-Palatinate as a case of “moderate pluralism” (Jun et Cronqvist, 2020:306 sqq.), with the SPD and CDU dominating the political scene. The two parties see themselves as the “main competitors for voters’ favour”, (ibid.: 305) thus making it comparatively more difficult for smaller parties to assert themselves in Rhineland-Palatinate than at the national level. Even the voter bases of the Greens and FDP — which served in the state government prior to the election — are unstable, meaning that both formations have had to gain experience in the extra-parliamentary opposition (ibid.: 306). Other small parties succeeded in entering the Landtag only in isolated cases: the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) in 1947; the German Reich Party (DRP) in 1959; the National Democratic Party of Germany (NPD) in 1967 and the AfD in 2016.

The 2021 election represents a caesura in this respect because the AfD, in spite of its losses, was able to reconfirm its presence in the state parliament. On the other hand, with the Free Voters entering parliament, the number of parties represented in the regional assembly increased from five to six for the first time in history. The spectrum previously ranged from two to five parties. While the dominance of the two major parties and moderate pluralism will remain after the 2021 election, parliamentary fragmentation, segmentation, and pluralisation are visibly increasing.

According to the Michigan model, which is well established in electoral sociology, it is above all the factors of identification, issues and candidates that determine voter behaviour. The post-election survey for the 2021 state election run by Infratest dimap shows interesting findings in this regard (John, 2021:11). Particularly SPD, Greens and CDU voters opted for their parties out of conviction. Compared to other parties, the CDU and FDP benefited from a strong party identification of the electorate: 30% of CDU voters and 21% of FDP voters gave party loyalty as the reason for their voting decision. 8 Voters for the Greens (72%) and the AfD (71%) were the most issue-oriented, but the Free Voters (64%) and the FDP (63%) were also able to convince voters through content. 9 According to the electorate, the decisive content-related issues in this election related to the following topics: social security (22%), economy (20%), education (17%), environment/climate (16%), COVID pandemic (12%), crime/internal security (8%) and immigration (5%) (John, 2021:11).

In the voters’ assessment of party competence, the SPD has an advantage over its main competitor, the CDU. The SPD is ahead of the CDU in dealing with the pandemic and in the areas of social justice, schools/education and the economy. The SPD also scores better than the CDU on climate protection but lags far behind the Greens here. Only in the area of transport is the CDU considered more competent than the SPD (ibid.: 8 sqq. ; Forschungsgruppe Wahlen e.V., 2021:2).

Following the Michigan model, the popularity of the Spitzenkanidaten also affects party competition. The citizen-oriented style of politics of former Minister President Kurt Beck (SPD), nicknamed the “state father,” (Borucki & Jakobs, 2020) was continued by the incumbent Minister President Malu Dreyer (SPD) who was therefore granted the informal title of “state mother”. The popularity of her style of government led to a predictable incumbent bonus, which is also confirmed by the polls comparing her to her direct competitor, Christian Baldauf (CDU). In a (virtual) direct election for the office of Minister-President, Baldauf lost to his opponent Dreyer by 28% to 56% (Infratest Dimap, 2021b). The discrepancy in the measured popularity ratings is even more striking; while 71% of respondents are (very) satisfied with Dreyer, Baldauf has to put up with 33% (very) satisfied (Infratest Dimap, 2021a). One of the reasons for this could be Baldauf’s relative lack of notoriety among Rhineland-Palatinate’s population. The Süddeutsche Zeitung ran a headline “Who knows this man?” above a picture of Christian Baldauf on 25 February 2021 — barely two and a half weeks before the election. The article referred to a survey by Südwestrundfunk, according to which around 40% of respondents did not know the CDU’s top candidate, even though he had been the Rhineland Palatinate CDU chairman between 2006 and 2011 and has since been deputy chairman. According to exit polls, 51% of SPD voters chose their party because of Dreyer, while only 23% of CDU voters made their decision because of Baldauf (John 2021:11).

Geographical explanatory factors

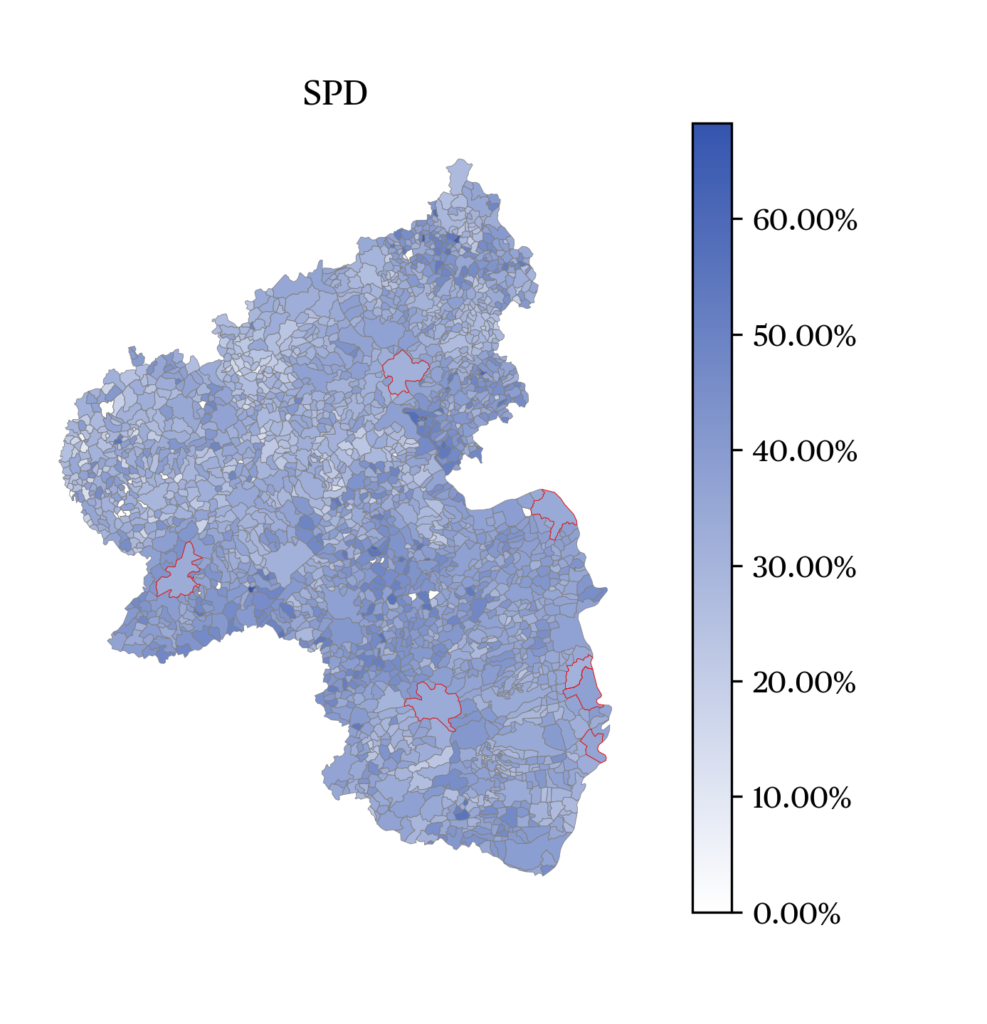

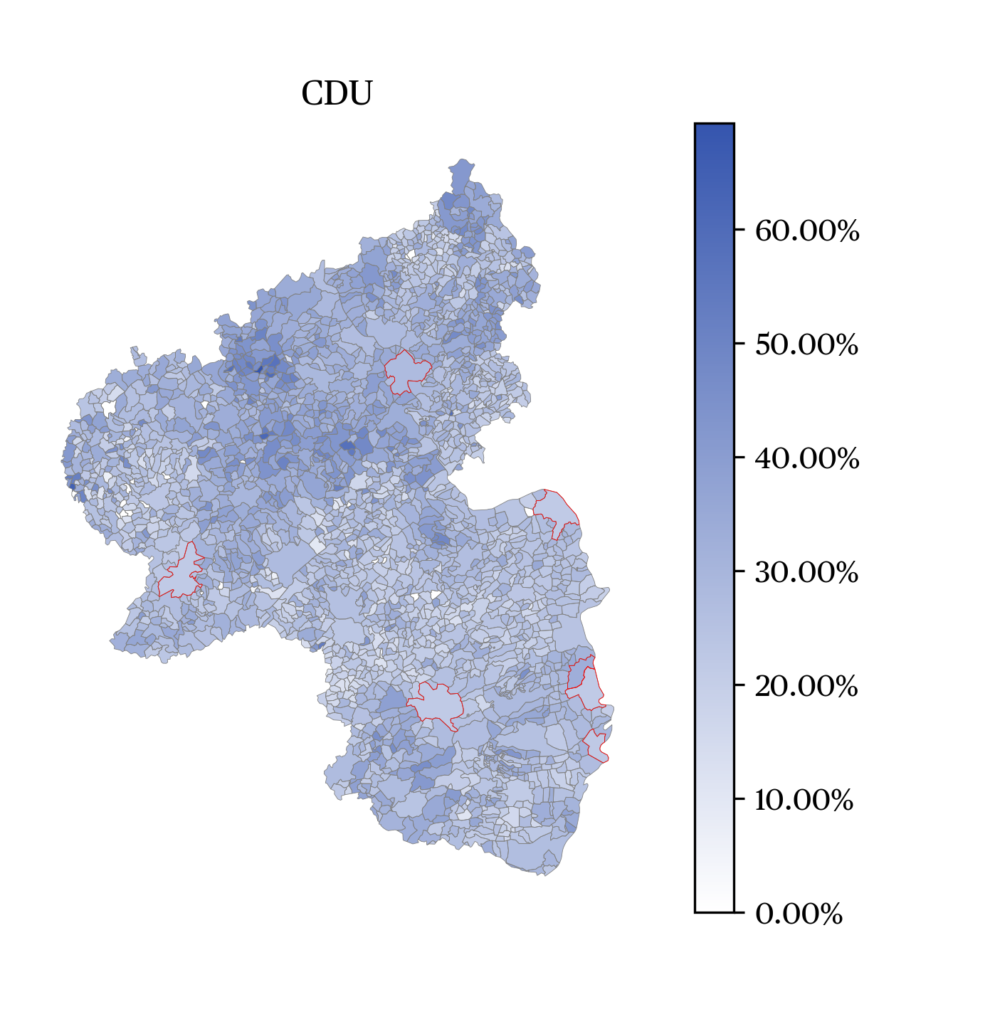

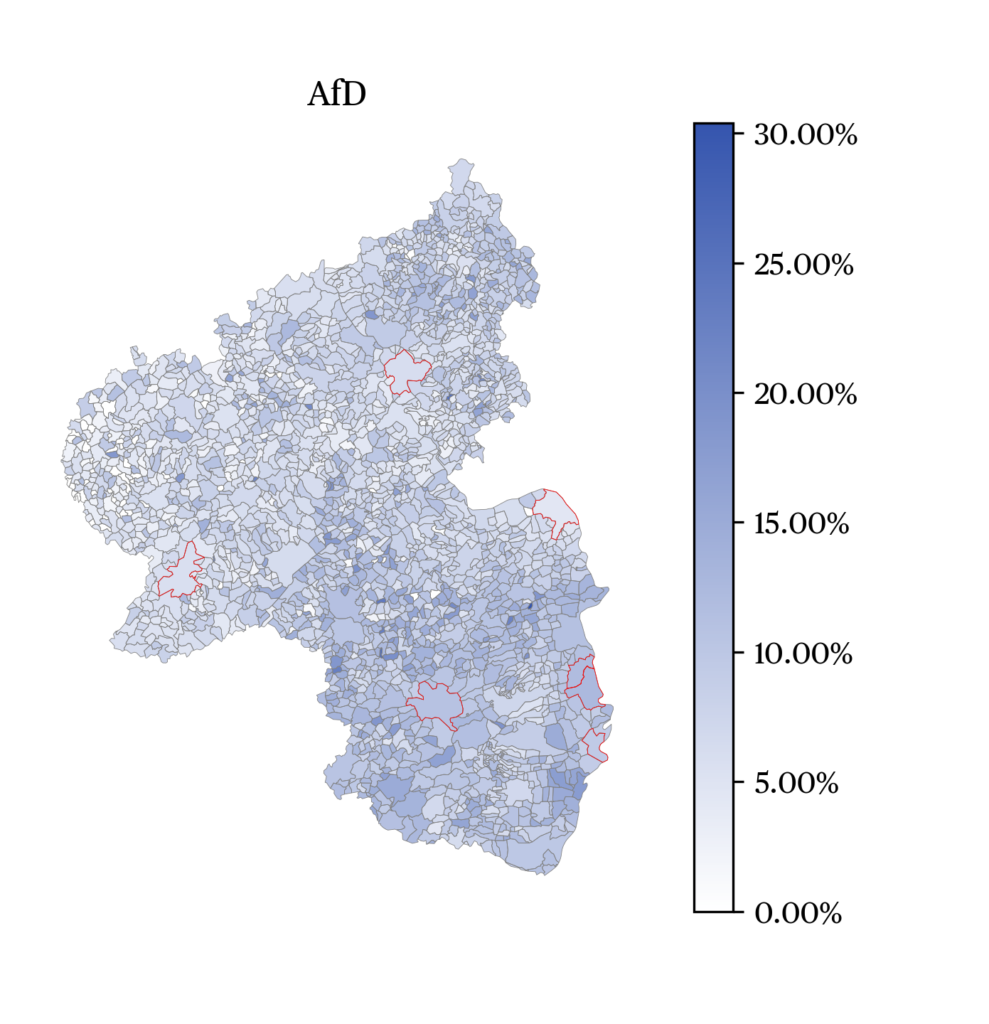

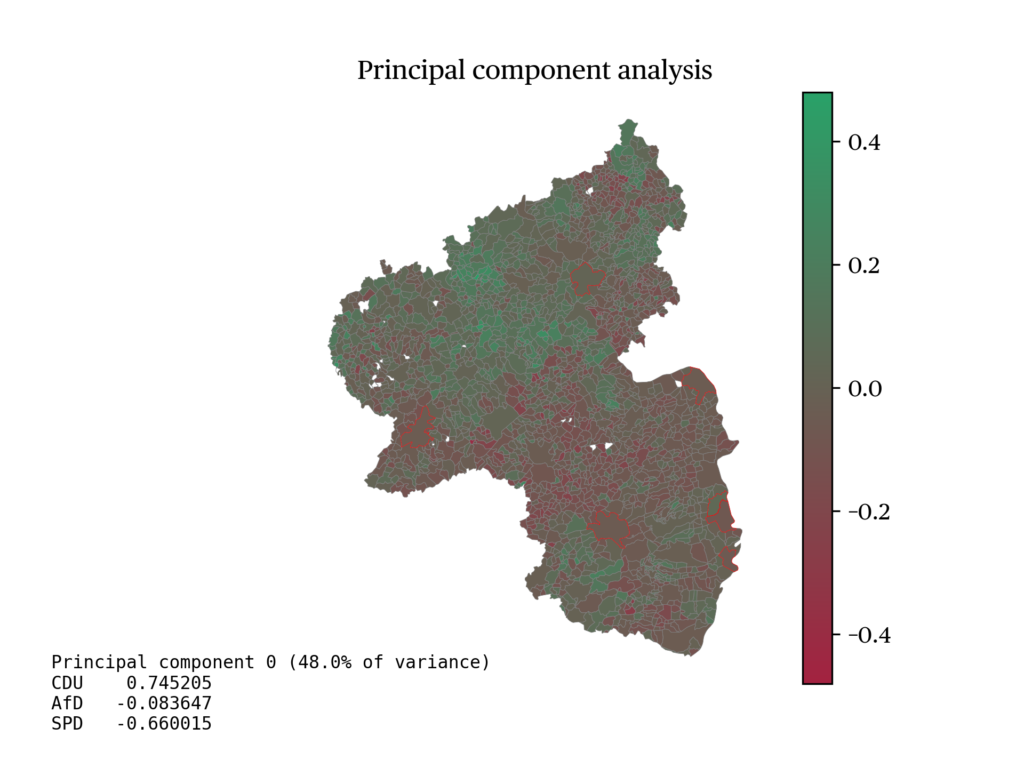

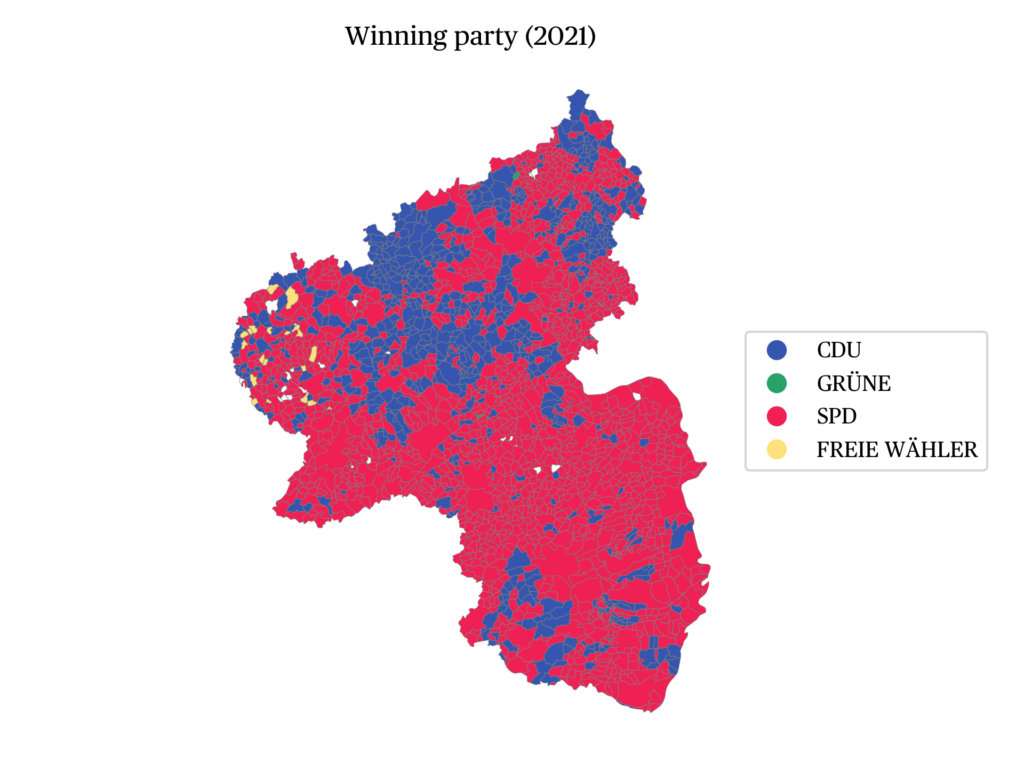

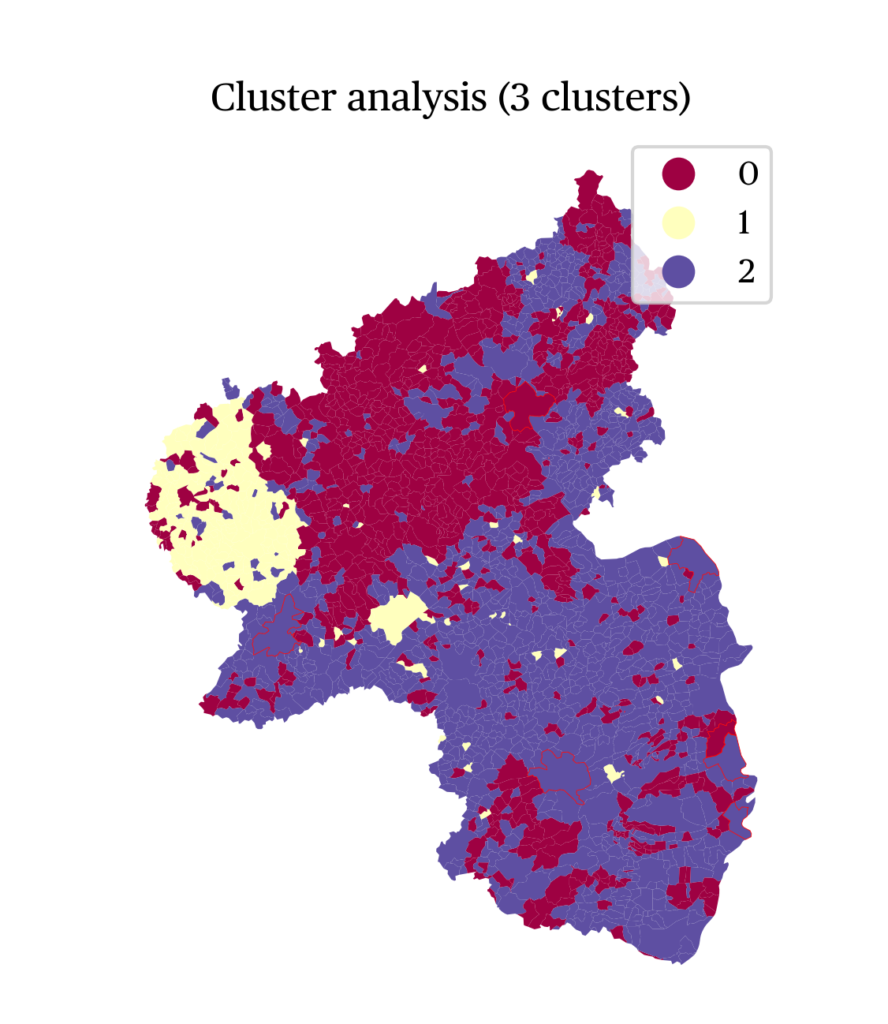

In addition to the three central factors of the Michigan model, the political maps provide important insights into the political processes. As shown in figure a, there are many SPD and CDU voters in almost all constituencies. However, the SPD is concentrated in the central part of the map, while the CDU performs best in the country’s north and southwest. As a principal components analysis (figure b, above) suggests, 49% of the difference in communal results from the regional average is explained by the fact that there are more CDU voters, fewer SPD voters and fewer AfD voters in these constituencies. Figure a also shows that the AfD was able to score well in the rural areas in the south of the Land.

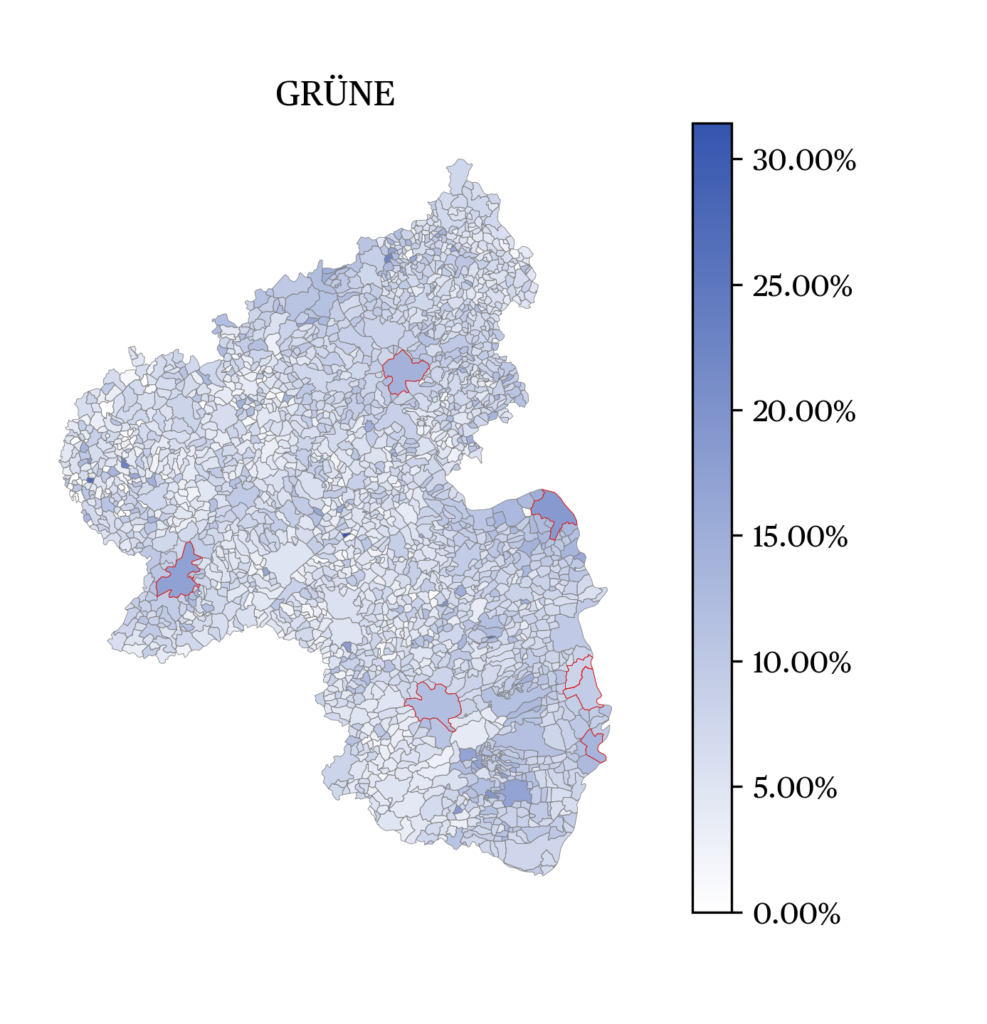

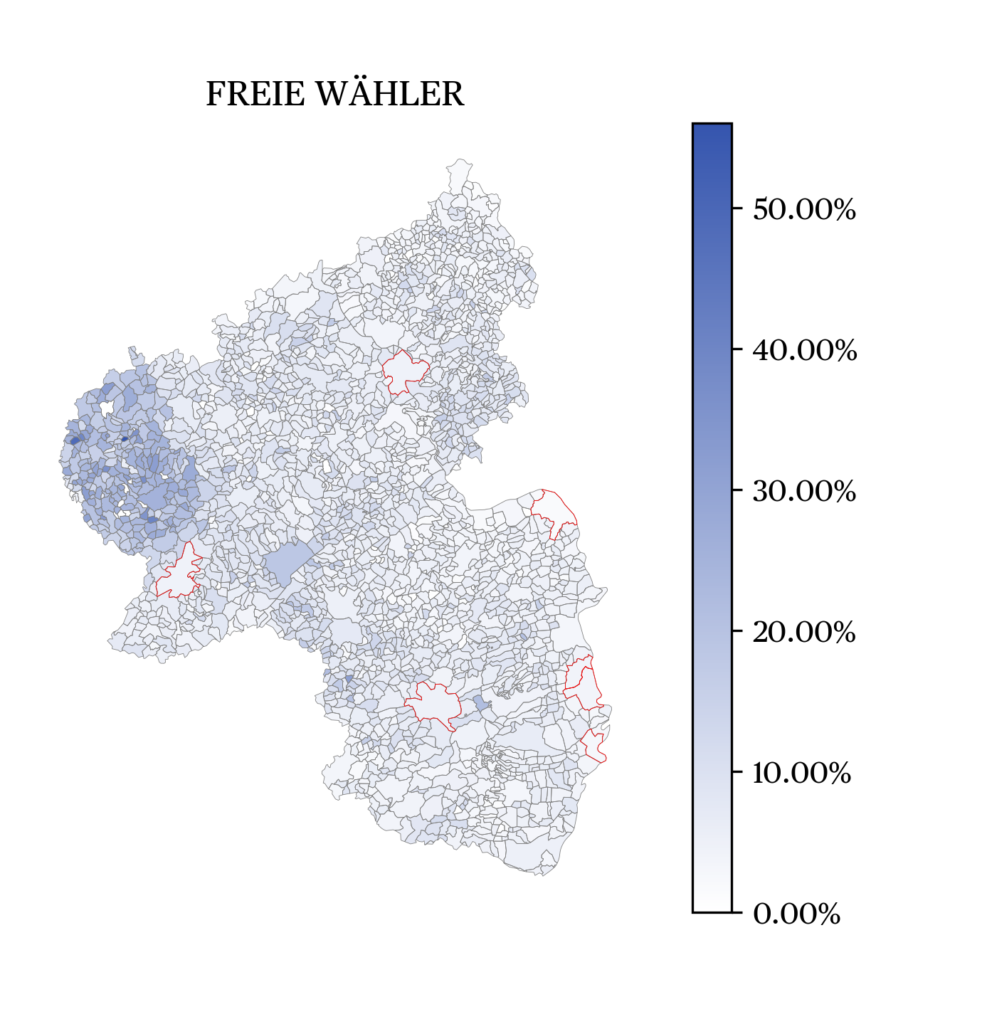

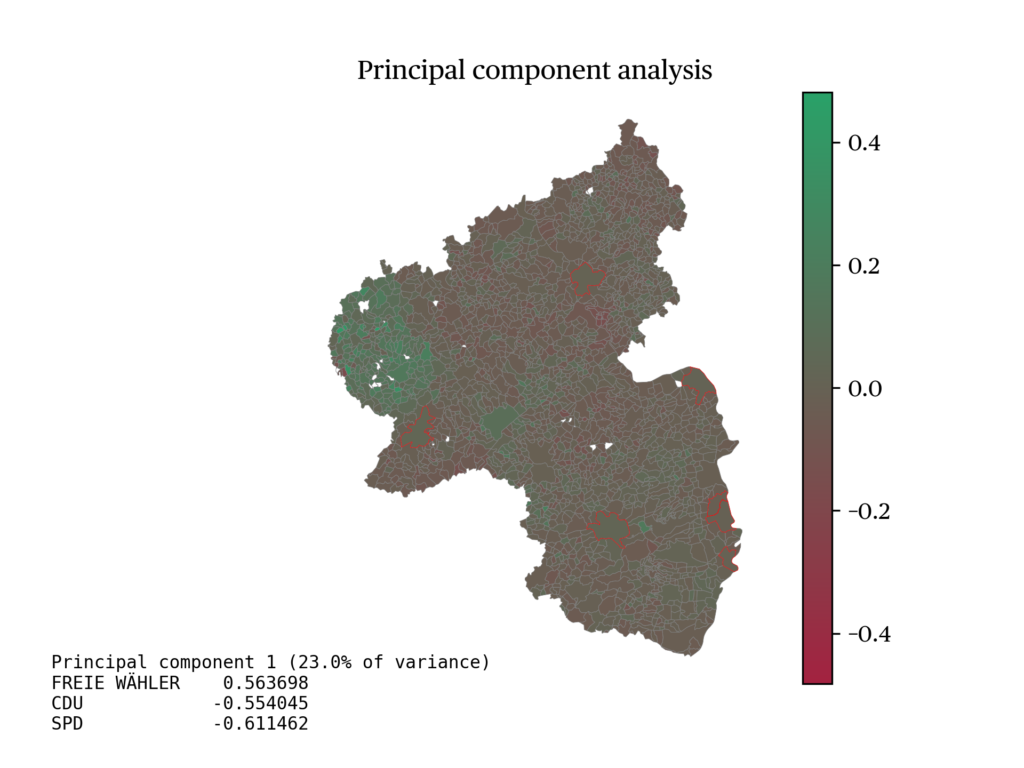

The same figure shows a typical trend for the Greens: the party won high shares of the vote in urban areas and university towns such as Mainz, Trier, Koblenz and Landau. While the political map does not provide much information on the FDP, with only a few districts in the North-West of the state appearing to be highlighted, the constituency of Bitburg-Prüm, in which the Free Voters achieved 21.3%, stands out. Their regional success in the Eifel can partly be explained by the popularity of their Spitzenkandidat Joachim Streit (Free Voters), who grew up in the region. Through intensive door-to-door campaigning, he managed to get elected mayor of Bitburg and later rose to the position of district administrator (Ludwig, 2021). As figure b shows, the comparatively strong result of the Free Voters coincides with weak performance — compared to the state average — of the CDU and SPD in this region.

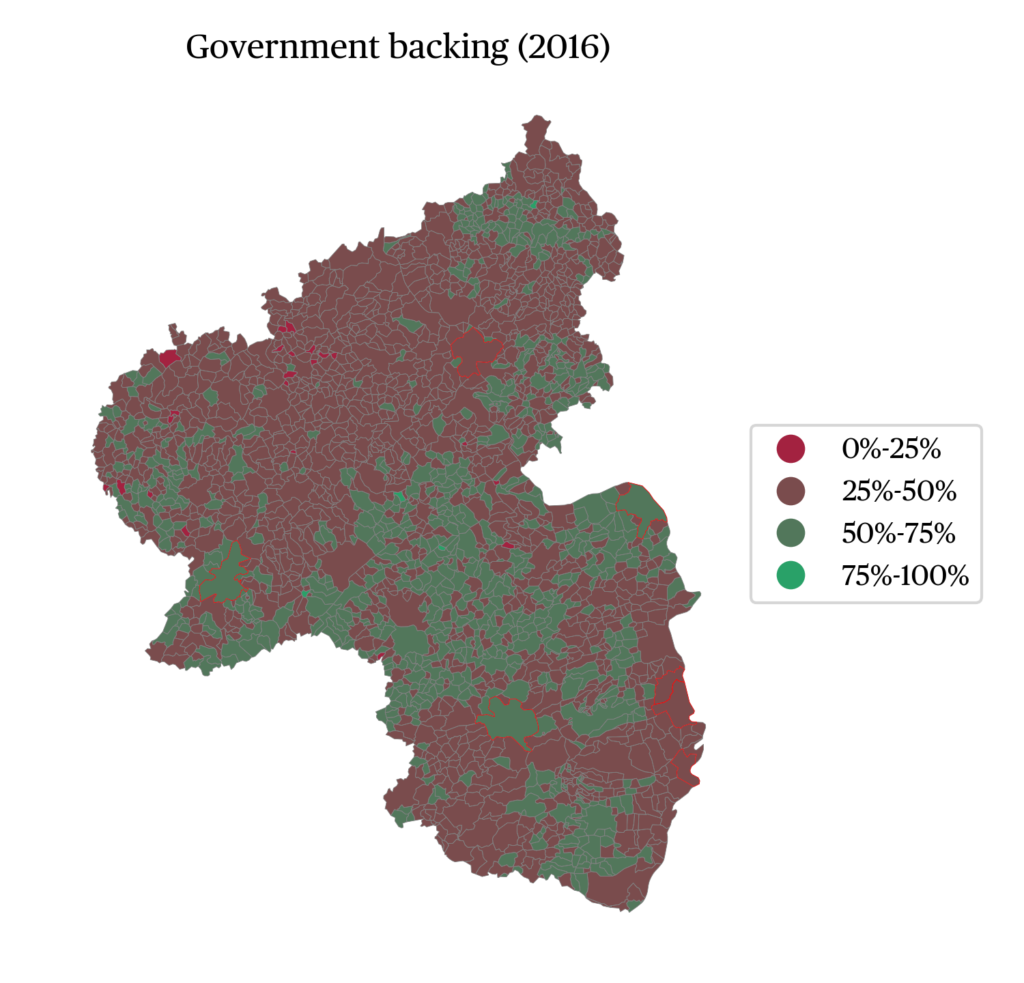

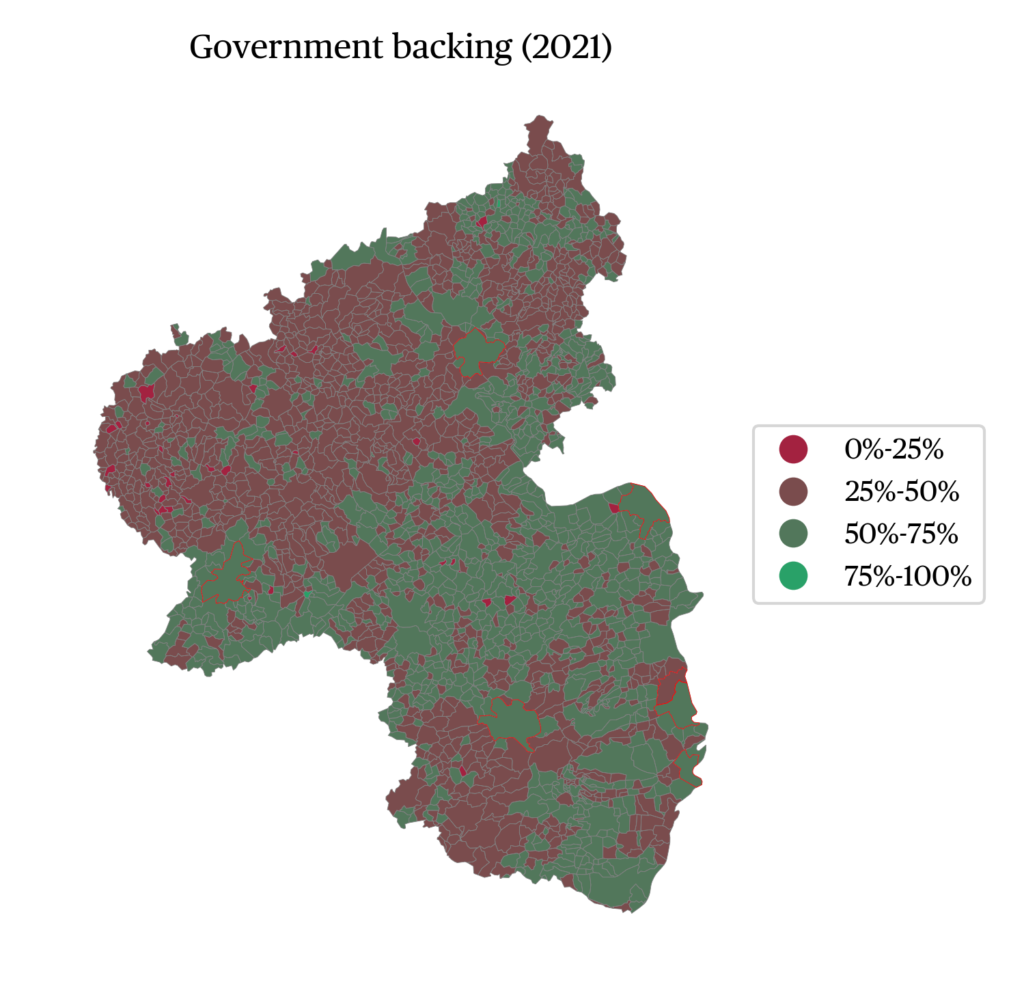

The cluster analysis (figure d) confirms this clear North/South cleavage as well as Bitburg-Prüm’s specific position. The map showing government support in the individual regions shows a similar picture (figure c, left). Again, the already familiar pattern of a North/South divide is discernable. However, here the Bitburg-Prüm constituency merges with the rest of the North, where, in large parts, less than half of the population is satisfied with the government. Satisfaction with the government has spread further in the south and centre of the country since 2016. In this area, the green indicator shows that in significantly more districts than five years ago, more than 50% of the population supports the 2016-2021 government (figure c, right).

Perspectives

The widespread satisfaction with the incumbent government made a continuation of the previous government model likely. On the day following the election, Minister-President Dreyer announced in an interview with Südwestrundfunk: “I’m talking to my current coalition partners [Greens and FDP; author’s note] […] We want to continue the traffic light [Ampel, that is red, yellow green], I’ve never made that a secret.” (Welt Online, 2021) The political scientist and expert on Rhineland-Palatinate, Uwe Jun, also sees “no real alternative to a new edition of the alliance” (ibid.). Even before the election, and especially after the announcement of the final official result — which arithmetically allows an alliance of SPD, Greens and FDP — the relaunch of the traffic light coalition was the most likely scenario for the coming legislature. Dreyer had already rejected a “grand coalition” consisting of SPD and CDU: “The voters would be quite surprised if I were to say now: We are going in that direction.” (ibid.) A centre-right alliance consisting of CDU, FDP (alternatively with the Free Voters) and AfD is not a realistic option. On the one hand, the CDU categorically rejects any government cooperation with the AfD, and on the other hand, there are very few convincing reasons for the FDP to opt for this option in terms of content and strategy. During a press conference on 30 April 2021, the coalition negotiations between the SPD, the Greens and the FDP were declared successfully concluded. The respective party congresses ratified the negotiated coalition agreement the following week. Of the nine ministries, some of which will be reorganised compared to the last legislature, the SPD will receive five and the two junior partners two each. According to Minister President Dreyer, each of the partners will be in charge of one of the three priority issues: Biotechnology (SPD), Climate Neutrality by 2040 (The Greens), Future of Inner Cities (FDP) (SWR.de, 2021). Looking at the negotiated coalition agreement, it seems that the green light of the traffic light shines brightest, although care was taken to ensure that each of the coalition partners retains its profile (Tagesschau.de, 2021).

In conclusion, the SPD benefitted from its competent handling of the central issues of state politics, especially from the confident handling of the pandemic by its incumbent Minister President. Contrary to the national trend, the party emerged as the strongest force. On the other hand, the CDU suffered a clear defeat, partly due to a rather unpopular top candidate and growing dissatisfaction with the nationwide Covid crisis management of the CDU/CSU-led federal government. Voters confirmed their satisfaction with the Greens’ and the FDP’s government work. While the Greens rode on the upward wave of the federal party’s trends and improved on their result of 2016, the FDP suffered losses but remains in parliament and government. After the AfD’s re-entry into the state parliament, the Free Voters’ success represents a turning point in Rhineland-Palatinate, as they form a sixth parliamentary group for the first time.

Concerning the upcoming federal election, it is not clear whether this state election triggered particular trends. The SPD was able to gain one percentage point (from 16% to 17%) in the Sunday poll for the federal election that followed the Rhineland-Palatinate vote. Whether this is a “Rhineland-Palatinate effect” cannot be determined with certainty, as the party has already lost this marginal bonus again and stands (as of mid-April) at 15 percentage points (Infratest Dimap, 2021c). This year, it is particularly likely that federal politics itself, especially the handling of the pandemic and the popularity of the Spitzenkandidaten, will have a more significant influence on the outcome of the federal election. Moreover, the signal effect of a traffic light coalition in Rhineland-Palatinate for federal politics is limited. The example of Rhineland-Palatinate shows the viability of this currently unique government option under the leadership of the SPD. Current polls, however, point to a different power balance in the federal government, i.e. a traffic light under Green, not Social Democratic leadership. Thus, the significance of this example appears limited (Tagesschau.de, 2021).

In addition, other issues and personnel questions may be decisive for a successful compromise in the form of a coalition agreement. Sufficient overlap in quantitative and qualitative form between the SPD, the Greens and the FDP at the federal level can not be presumed at that point. The Rhineland-Palatinate experience is thus difficult to generalise.

Bibliography

Borucki, I. and Jakobs, S. (2020). Die Regierung Beck. Sein Führungsstil als nahbarer Landesvater. In Glaab, M., Hering, H, Kißener, M., Schiffmann, D. and Storm, M. (Eds.), 70 Jahre Rheinland-Pfalz. Historische Perspektiven und politikwissenschaftliche Analyse. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. pp. 219-240.

Burkhart, S. (2007). Der Einfluss der Bundespolitik auf Landtagswahlen. In Schmid, J. and Zolleis, U. (Eds.), Wahlkampf im Südwesten. Parteien, Kampagnen und Landtagswahlen 2006 in Baden-Württemberg und Rheinland-Pfalz. Berlin: LIT Verlag. pp. 191-207.

Detterbeck, K. and Renzsch, W. (2008). Symmetrien und Asymmetrien im bundesstaatlichen Parteienwettbewerb. In Jun, U., Haas, M. and Niedermayer, O. (Ed.): Parteien und Parteiensysteme in den deutschen Ländern. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. pp. 39-55.

Drobinski, M. & Niewel, G. (2021). Wer kennt diesen Mann? Süddeutsche Zeitung, n°46, 25 February 2021. p. 3.

Forschungsgruppe Wahlen e.V. (2021). Landtagswahl in Rheinland-Pfalz 2021. Analyse brève. Online [last accessed 27 April 2021].

Infratest Dimap (2020). PoliTREND Rheinland-Pfalz Dezember 2020. Repräsentative Umfrage im Auftrag des SWR. Online [last accessed 20 April 2021].

Infratest Dimap (2021a). PoliTREND Rheinland-Pfalz Januar 2021. Repräsentative Umfrage im Auftrag des SWR. Online [last accessed 20 April 2021].

Infratest Dimap (2021b). PoliTREND Rheinland-Pfalz Februar 2021. Repräsentative Umfrage im Auftrag des SWR. Online [last accessed 20 April 2021].

Infratest Dimap (2021c). Sonntagsfrage Bundestagswahl. Online [last accessed 27 April 2021].

John, S. (2021). Landtagswahl Rheinland-Pfalz 2021. Ergebnisse und Analysen. böll.brief — Demokratie und Gesellschaft #22. Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung.

Jun, U. and Cronqvist, L. (2020). Der Wandel des Parteienwettbewerbs in Rheinland-Pfalz. Von der CDU-Dominanz zur SPD geprägten Landespolitik. In Glaab, M., Hering, H., Kißener, M., Schiffmann, D. and Storm, M. (eds.), 70 Jahre Rheinland-Pfalz. Historische Perspektiven und politikwissenschaftliche Analyse. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. pp. 305-327.

Landeswahlleiter (2021). Landesergebnis Rheinland-Pfalz. Endgültiges Ergebnis der Landtagswahl 2021. Online [last accessed 20 April 2021].

Leininger, A. and Wagner, A. (2021). Wählen in der Pandemie: Herausforderungen und Konsequenzen. Zeitschrift für Politikwissenschaft. Online [last accessed 21 April 2021].

Ludwig, G. (2021). Joachim Streit (Freie Wähler): Der Exot aus der Eifel, SWR.de. Online [last accessed 2 June 2021].

Mueller, J. E. (1970): Presidential popularity from Truman to Johnson. The American Political Science Review (64/1), pp. 18-34.

SWR.de (2021). Ampelkoalition in Rheinland-Pfalz wird fortgesetzt. Online [last accessed 4 May 2021].

Tagesschau.de (2021). Eine Ampel mit viel Grün. Online [last accessed 4 May 2021].

Welt Online (2021). Parteien analysieren Wahl: Dreyer kündigt Gespräche an. Online [last accessed 27 April 2021].

Les données

Notes

- More information on the specific features of the Rhineland-Palatinate electoral system can be found on the website of the Landtag in Rhineland-Palatinate.

- Sonntagsfrage, February 2021 : CDU 31%, SPD 30% (Infratest Dimap, 2021b) ; January 2021 : CDU 33%, SPD 28% (Infratest Dimap, 2021a) ; December 2020 : CDU 34%, SPD 28% (Infratest Dimap 2020).

- 2.5% of the vote at state level and 2.8% at constituency level.

- 1.7% of votes at state level, no direct candidates.

- 1.1% of the vote at state level and 0.4% at constituency level.

- 1.0% of the vote at state level and 0.1% at constituency level.

- Other candidate parties, individuals or voter communities with less than 1% of the votes at state and constituency level: Pirates (Greens/EFA), ödp (Greens/EFA), Klimaliste, Basisdemokratie, Dr. Moritz, SIGGI WÄHLEN.

- Greens : 18%, SPD : 15%, AfD : 12%, Free Voters : 10%.

- CDU : 44%, SPD : 31%.

citer l'article

Marius Minas, Parliamentary Election in Rhineland-Palatinate, 14 March 2021, Sep 2021, 45-51.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue