Parliamentary election in Serbia, 17 December 2023

Maja Nastić

Full Professor of Law at the University of NišIssue

Issue #5Auteurs

Maja Nastić

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

Introduction

In this text, we analyse the context and results of the parliamentary election held in the Republic of Serbia on December 17, 2023. This election was announced in an atmosphere of major political and social tensions caused by two mass shootings in May 2023. 1 These events caused disruption in society, leading to mass demonstrations that began on May 12 and continued for the next 27 weeks in Belgrade and many other cities in Serbia. The protests were organised under the slogan ’Serbia against violence’ and included representatives of opposition parties, civil society, and other organisations. On July 18, the National Assembly established an Inquiry Committee to investigate the facts and circumstances surrounding the shootings, identify any lapses in the exercise of authority and recommend appropriate actions, as well as to determine accountability among officials and propose corrective measures. Marinika Tepić, the head of the opposition parliamentary group ’United’ (Ujedinjeni), was elected president of the committee by a majority vote. However, three days later, the National Assembly announced that it was suspending the work of this committee at the request of the victims’ families’ representatives.

This contributed to the further aggravation of the political situation, which was characterized by growing social dissatisfaction. Furthermore, at the end of September, an armed incident in northern Kosovo 2 led to the deaths of a Kosovo police officer and three other members of an informal armed group of Serbian nationality. Serbia’s foreign policy position was greatly impacted by this event (CRTA, 2023). At that time, some media outlets reported on the mobilisation of the party infrastructure of the leading Serbian Progressive Party and part of the opposition, which requested early parliamentary and local elections in Belgrade (CRTA, 2023).

Finally, on October 30, 2023, the Government proposed dissolving the National Assembly to the President of the Republic (Government of Serbia, 2023). According to the government announcement, holding the new parliamentary elections in these circumstances would ensure a higher degree of democracy, reduce tensions created between opposition groups, reject exclusivity and hate speech, and affirm the right to freely express one’s opinion and European values, as stated in the government announcement.

Based on Article 109, paragraphs 1 and 5, of the Constitution, as well as Article 21, paragraph 1, of the Law on the President of the Republic, President Aleksandar Vučić dissolved parliament and called for early parliamentary elections on December 17. On the same day, the Speaker of the Parliament called for local elections in 65 of the 174 self-governing units, including the capital, following the resignation of mayors from the ruling party starting on September 28. The resignations mainly occurred in municipalities where it was estimated that the representatives of the ruling coalition could regain power. Although the mayors justified their resignation on moral grounds or on the basis of saving on the budget and avoiding to vote twice in a short period, the real reasons could be found in the well-known tactics of the ruling coalition led by the Serbian Progressive Party.

On November 16, the election to the Assembly of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina was set to be held on the same day. In Serbia, it is not uncommon to see multiple elections held on the same day. In 2022, presidential and parliamentary elections were held simultaneously, as were parliamentary, provincial and local elections in 2020 and 2016.

The parliamentary elections in December 2023 are the second early elections in less than two years and the third elections over a period of four years. Since the introduction of the multi-party system in 1990, there have been 14 parliamentary elections, of which 10 were early elections. Regular parliamentary elections were only held four times in over 30 years (Figure a).

| Election date | Mandates won | Turnout |

| 9th December 1990 | Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS): 194 Serbian Renewal Movement (SPO): 19 Democratic Party (DS): 7 Parties of national minorities: 14 | 71.49% |

| 21st September 1997 | Socialist Party of Serbia-The Yugoslav Left party-New Democracy (SPS-JUL-ND): 110 Serbian Radical Party (SRS): 82 Serbian Renewal Movement (SPO): 45 Aliance of Vojvodina Hungarians (SVM): 4 | 57.40% |

| 6th May 2012 | Serbian Progressive Party (SNS): 73 Democratic Party (DS): 67 Socialist Party of Serbia-Party of United Pensioners of Serbia (SPS-PUPS): 44 Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS): 21 | 57.76% |

| 21st June 2020 | Serbian Progressive Party (SNS): 188 Socialist Party of Serbia-Party of United Pensioners of Serbia-United Serbia (SPS-PUPS-JS): 32 Serbian Patriotic Alliance (SPAS): 11 | 48.88% |

Source: CRTA.

Unlike in other European countries, in Serbia early parliamentary elections are the norm in Serbia. Frequent election cycles can indicate unstable political conditions or an inability to form a stable parliamentary majority, which has not been the case since 2014 (Jovanović & Simić, 2023). The government calls early elections, and the best moment to preserve power is chosen using strategic maneuvers. The political scene is constantly tense due to frequent election cycles, creating the impression of a permanent pre-election atmosphere. The extent to which this electoral trend adversely affects the achievements of democratic governance is best confirmed by the Freedom House Report prepared at the beginning of 2020. Serbia then shifted from being a semi-consolidated democracy to a hybrid regime that combines authoritarian practices with democratic competition (Damnjanović, 2020). Serbia is a parliamentary democracy with competitive multiparty elections. However, the ruling Serbian Progressive Party has constantly eroded political rights and civil liberties in recent years, putting pressure on independent media, political opposition, and civil society organisations (Burazer, 2023).

Legal framework

The Constitution of the Republic of Serbia (2006) recognizes the basic principles of the electoral system. While it does not specify the exact apportionment method to be used, the Constitution implicitly requires a system of proportional representation. It identifies the following principles of the electoral system: universal suffrage, equal suffrage, free suffrage, secret suffrage, and direct suffrage. These principles are common to all electoral systems and represent a specific aspect of the European constitutional heritage. However, these principles can only be upheld if certain general conditions are met: respect for fundamental rights, regulatory stability and stability of electoral law, and procedural safeguards. Furthermore, the Constitution of Serbia sets out the timeframe within which elections must be announced and conducted, an uncommon practice in comparative constitutional law (Pajvančić & Marinković, 2022).

The Serbian electoral legislation is not homogenous, being contained within several legislative acts. Parliamentary elections are primarily regulated by the 2022 Law on the Election of Members of Parliament, the 2009 Law on Unified Voter Registration, and the decisions and instructions of the Republic Electoral Commission (REC). The legal framework was significantly revised in early 2022, following a two-party dialogue process between the ruling party and the opposition. The inter-party dialogue was mediated by the European Parliament (EP). The first meeting was held on 9-10 October 2019, with a focus on improving the conditions for holding parliamentary elections; the second took place on 14-15 November 2019, with additional initiatives proposed on the basis of the report of the European Commission mission and the OSCE/ODHIR. The final round of the first phase of interparty dialogue was held on 12-13 December (Pásztor, 2022). It resulted in the adoption of sixteen measures to improve the conduct of the electoral process (OSCE, 2022). These include the creation of a Temporary Supervisory Body and other media-related initiatives to promote more equal political representation, include the extra-parliamentary opposition in the Republic Electoral Commission, avoid voter intimidation, and prevent the misuse of public offices and resources.

The OSCE Report on Presidential and Early Parliamentary Elections, issued in August 2022, offered a number of recommendations. These recommendations, rooted in OSCE’s extensive experience and expertise in electoral matters, are crucial for further enhancing the quality of the electoral process in Serbia. The report emphasised the need for further legal review to address challenges related to the misuse of administrative resources and access to the media (OSCE, 2022). The authorities should take measures to the prevent abuse of office and state resources. Legislation should clearly draw the boundaries between the incumbent’s official duties and their campaigning activities. In order to ensure equal opportunities between the candidates, state activities must be clearly separated from party activities and the campaign must be regulated, with a particular focus on preventing the abuse of public funds and official positions. The report noted that most TV channels with national frequency and print media promoted the government’s policies. Those few media outlets that developed alternative viewpoints were limited in their ability to provide an effective counterbalance and expose voters to a diversity of political views.

Electoral system

In 1990, the first multiparty elections were conducted using majority voting. Since 1992, a proportional electoral system has been implemented. Immediately after the mass demonstrations that ended the rule of Slobodan Milošević on 5 October 2000, the outgoing Assembly adopted a new electoral law. Since then, Serbia has used proportional representation based on the D’Hondt’s method in its most extreme form, with the entire country forming one nationwide constituency. The National Assembly is unicameral, consisting of 250 members of Parliament elected for a four-year period on closed electoral lists. Mandates are assigned to declared lists of candidates that win at least 3% of the votes. The quotas of electorals list representing national minorities are increased by 35% if they win fewer than 3% of the votes.

Voters’ registration

Voting rights are granted to all citizens aged 18 or over on election day, except those deprived of legal capacity by court decisions. Voter registration is a passive process. The Ministry of State Administration and Local Self-Government is in charge of maintaining the Unified Voters’ List. Personalised data verification is possible in the Unified Voters’ List on the Ministry’s website and through the e-government portal. However, local self-government units do not practice exposing parts of the voter list to citizens. The lack of transparency in managing the voter list and voter registration and the low level of public confidence in its accuracy was highlighted in the 2023 elections (CESID, 2023). In addition, these elections were marked by organised voter migration, a type of electoral engineering involving the coordinated behavior of voters who temporarily change their residence to influence the election results in a local government unit where they do not usually live (CRTA, 2023).

In Serbia, voting is conducted solely at polling stations, with no possibility of electronic or email voting. Determining polling stations is, therefore, an essential element of the electoral process and is under the jurisdiction of the local electoral commission. The total number of registered voters in the 8,273 polling stations was 6,500,666. Voters who cannot vote at their polling station due to serious illness, old age, or disability can apply to vote outside the polling stations. The last election cycle has seen a noticeable increase in this type of voting (CRTA, 2023). Additionally, special voter lists were drawn up for members of the military and detainees of penal institutions. Voters abroad could apply to vote in Serbian diplomatic and consular representations (Figure b). Opening a polling station abroad requires registering at least 100 voters. The REC decided that voters from Kosovo could vote in 4 peripheral municipalities at 52 polling stations in Bujanovac, Raška, Kuršumlija, and Tutin.

| Elections | Number of polling stations abroad | Number of registered voters |

| 2023 | 81 | 32,216 |

| 2022 | 77 | 39,777 |

| 2020 | 40 | 13,251 |

| 2016 | 37 | 6,649 |

Source: CRTA.

Main contenders

Eighteen lists competed in the election, including a total of 2,817 candidates for MPs of which 1,205 were women. Although all candidate lists met the legal registration requirement to ensure a gender quota of at least 40%, only two lists were headed by women. Ten coalitions, six political parties, and two groups of citizens submitted electoral lists. Seven electoral lists of national minorities, including the Albanian, Bosnian, Croatian, Hungarian, Russian, and Vlach national minorities, were also registered.

Two major blocks were present in these elections: the first gathered around the ruling SNS and the ‘Aleksandar Vučić – Serbia must not stop’ list, and another aligned with the ‘Serbia Against Violence’ list led by the Party of Freedom and Justice together with the People’s Movement of Serbia, the Green-Left Front, and 11 other parties and movements.

The electoral campaign was marked by extreme polarisation, aggressive rhetoric, personal discreditation, verbal abuse, and inflammatory language. Although not a candidate in these elections, President Vučić assumed a central role in daily campaigning by being heavily involved in SNS events, giving him a dominant position in the campaign (European Parliament, 2024).

The campaign’s ability to provide a level playing field for all parties and candidates was greatly hindered by the disproportionate representation of pro-government discourse in the national media, especially on television. The Serbian opposition has faced significant hurdles for a long time due to its lack of access to the media. Despite the adoption of a law on public information and media in October 2023, the role of the media in this election campaign has remained unchanged.

Elections results

The final results of the election were announced on 12 January, with a voter turnout of 58,69% or 3,820,746 votes.

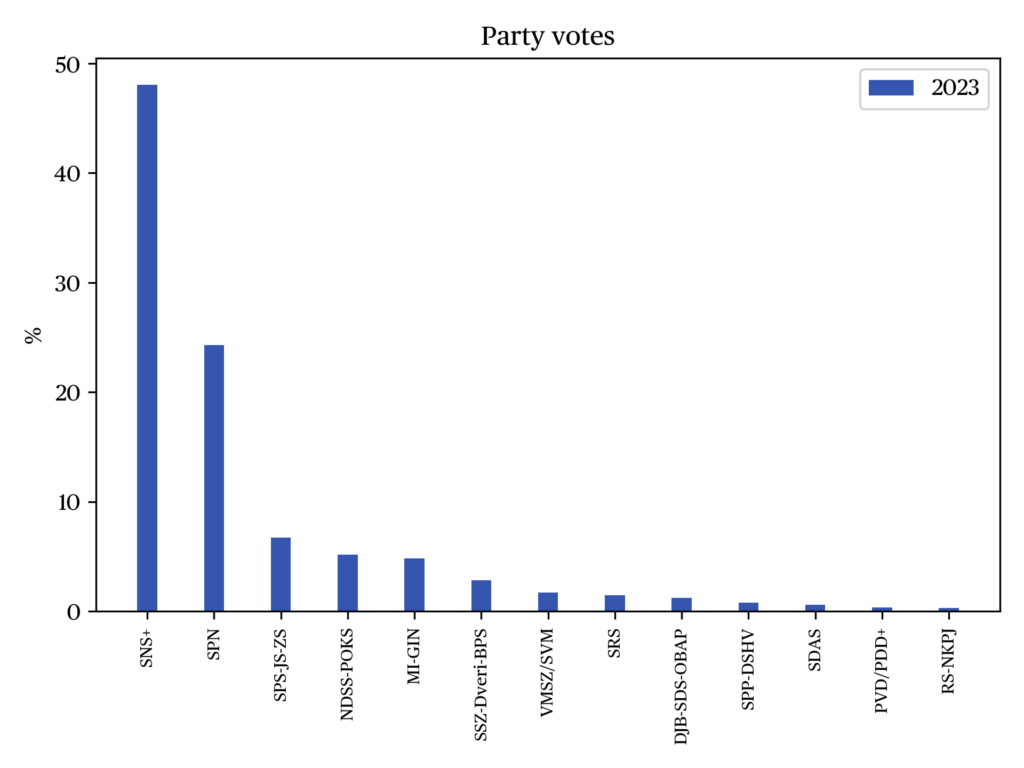

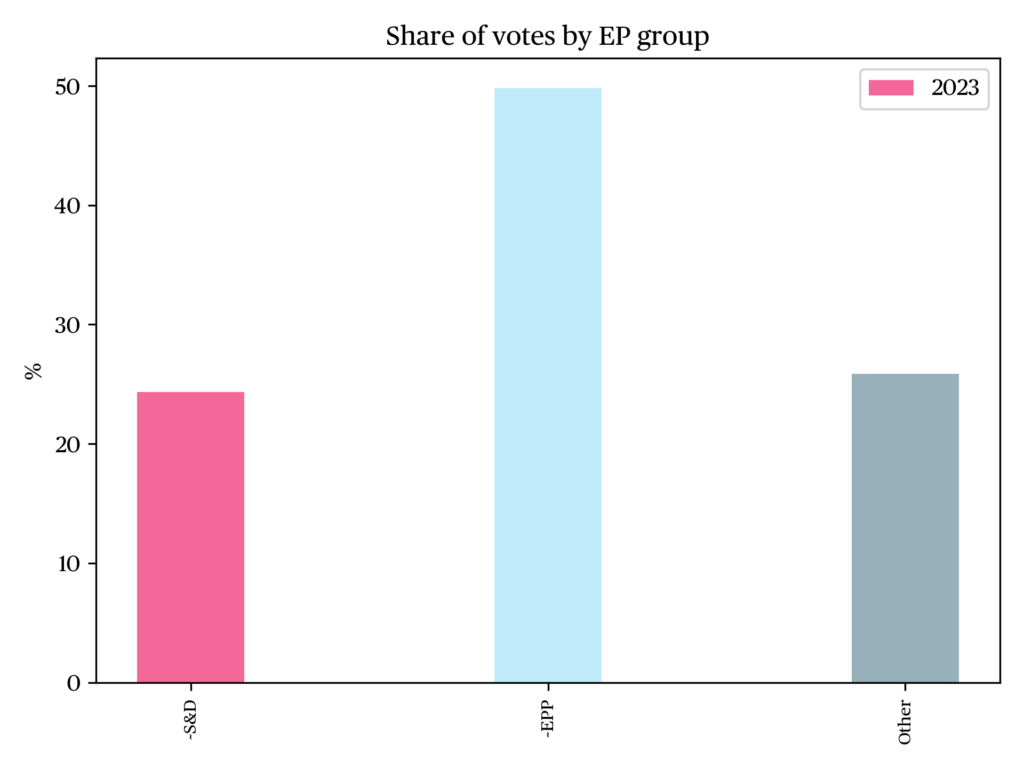

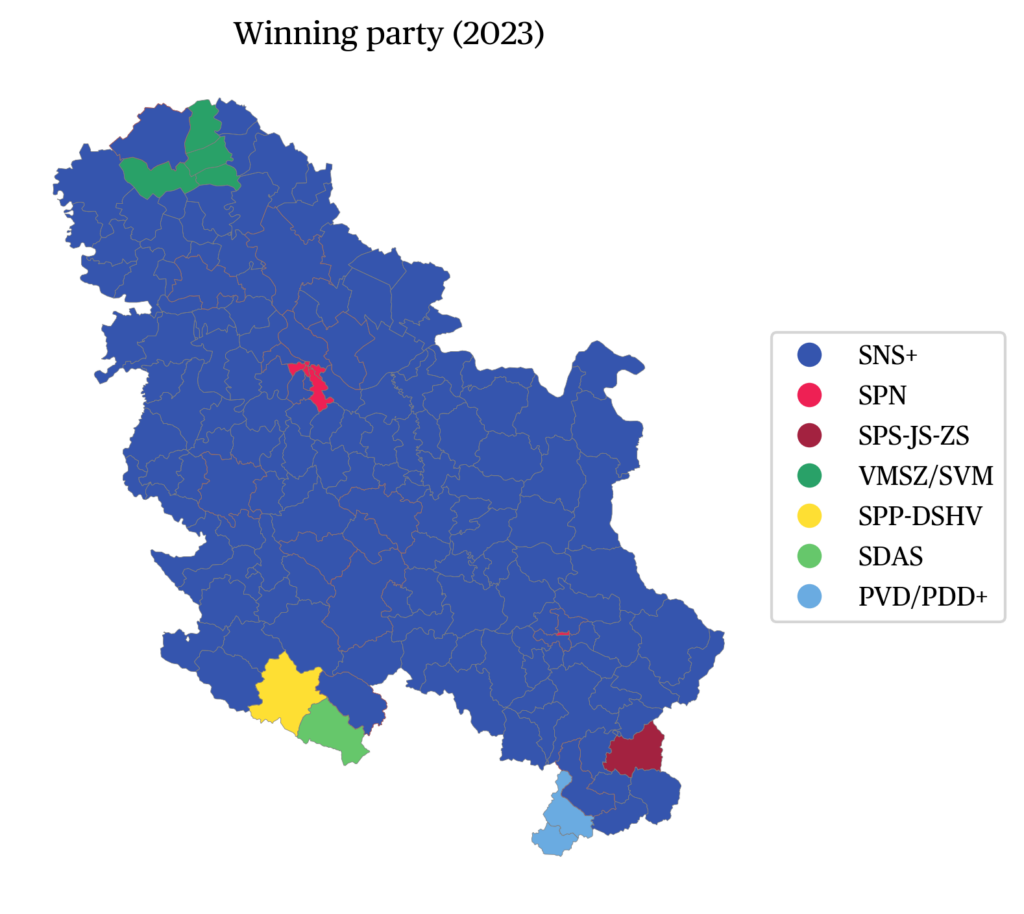

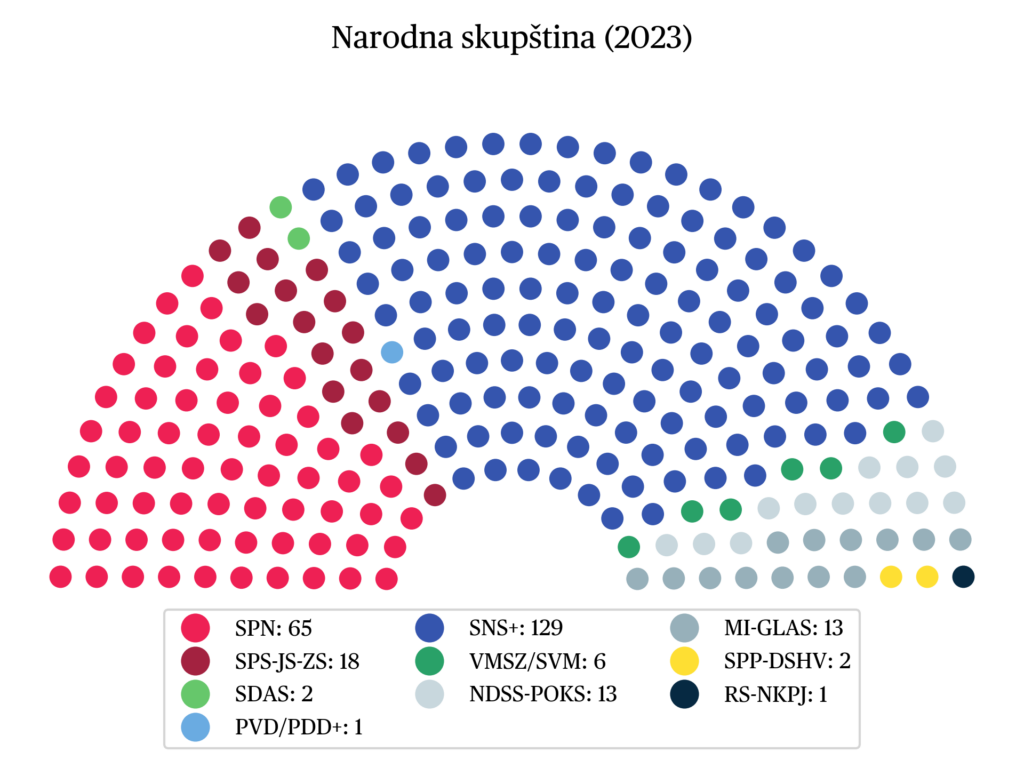

The Serbian Progressive Party (SNS), led by President Vučić, was the ultimate winner of the parliamentary elections. With 46%, the SNS won the absolute majority in the National Assembly with 129 out of 250 seats. At the same time, the Socialist Party of Serbia (SPS) experienced a significant decline in support, dropping from 13% to 6.5% 3 . The opposition was divided into several blocks. The first bloc was grouped under the ’Serbia against Violence’ list and consisted of members of the liberal democratic opposition, including 15 political parties and coalitions, and one trade union. The second block comprised right-wing political parties united by their opposition to the Franco-German plan for Kosovo. Of the right-wing electoral lists, only the Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS) reached the 3% threshold, achieving a vote share of 5%, while other right-wing parties fell below the threshold. Further right-wing parties, such as Dveri, Zavetnici, the Serbian People’s Party, and ‘Enough is Enough’, also fell below the threshold. In this election, Dr Branimir Nestorović’s ‘We, the voice of the people’ movement emerged as a new political player and won 5% of votes. Nestorović was initially part of the medical team of advisers to the Government of Serbia during the COVID-19 pandemic. He has consistently disputed the severity of the pandemic and frequently promoted narratives characterised as conspiracy theories, including those that undermine the efficiency of vaccination. This movement brought together people with anti-globalist, conservative, pro-Russian and conspiracist worldviews.

The results of the 2023 parliamentary elections were largely similar to those of the 2022 elections. However, there were also some minor changes, such as the SNS obtaining more votes than in the previous election. The democratic, pro-European opposition received approximately 300,000 more votes than in the 2016 and 2022 elections combined.

Post-election developments

On December 18, ‘Serbia Against Violence’ started daily protests in Belgrade, demanding that both the local and early parliamentary elections be repeated due to alleged irregularities. The opposition denounced cases of voter intimidation, vote buying, and the organised transportation of voters from inside and outside the country to polling stations. The ‘Serbia against Violence’ coalition presented evidence to the REC on December 23, 2023 and demanded to call and conduct a new election for the Belgrade City Assembly. Although most protests were peaceful, violence broke out on December 24 in Belgrade, leading to riot police using tear gas against protestors and arresting 38 individuals (ODHIR, 2024). The President and Prime Minister denied any claims of electoral fraud, referred to demonstrators as ‘thugs’, and targeted international observers, including the PACE head of delegation (Schennach et al., 2024).

The REC received 360 requests to annul the results of the parliamentary election, while the Local Election Committees (LECs) received 36 complaints concerning alleged irregularities. Of these, approximately 200 demanded the annulment of voting at all polling stations within the territory of an LEC or nationwide.

’Serbia against Violence’ submitted a request to resolve the electoral dispute to the Constitutional Court of Serbia on January 27, 2024. The Constitutional Court announced on February 9 that it had opened cases and assigned them to judges. The Constitutional Court has the legal authority to determine whether the election results were significantly influenced and can annul the electoral process partially or wholly through petitions. The Court is not bound by a specific deadline to resolve electoral disputes, and we are still awaiting its decision.

Meanwhile, the constituting session of the 14th Legislature of the National Assembly of the Republic of Serbia was held on February 6, 2024. The next day, on February 7, the European Parliament adopted a Resolution on the situation in Serbia following the elections. 4 The Parliament regretted that, as a result of the incumbent’s persistent and systematic abuse of the institutions and the media to obtain an unfair and undue advantage, the Serbian parliamentary and local elections held on December 17, 2023 deviated from international standards and Serbia’s commitments to free and fair elections. As a result, it considered that these elections had not been held under fair circumstances. Serbia was consequently urged to take all necessary measures to prevent future disinformation campaigns against election observers and to create an environment that permits both domestic and foreign observers can carry out their duties, cooperate with the ODHIR, the EU and the Council of Europe to implement the OSCE/ODHIR recommendations, and conduct a comprehensive audit of the unified voter registration system in order to correct any inaccuracies, including those relating to claims of voter migration. The European Parliament denounced the widespread unethical and biased media coverage favouring incumbents as well as the lack of media plurality during the election campaign. It also expressed concerns about government influence or control over many media outlets, which created an uneven playing field for opposition candidates during the campaign. The resolution called on the Serbian authorities to guarantee a transparent media environment and to significantly strengthen the protection of independent journalism.

Efforts are underway to address the electoral situation in Serbia. On 3 April 2024, due to the failure to form a majority in the Belgrade City Assembly following the 2023 elections, the Speaker of the Parliament called for new elections to be held on 2 June. In response to the situation, ODHIR established an Election Observation Mission following an invitation from the authorities of the Republic of Serbia. On April 29, 2024, the National Assembly formed the Working Group for the Improvement of the Electoral Process. 5 The task of the Working Group is to determine which legislative and other measures need to be implemented in order to fulfill all recommendations from the final ODHIR report, to prepare amendments to the relevant laws, as well as a proposal for recommendations on measures that should be implemented by other state bodies.

Acknowledgement: This article is a result of research financially supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (contract number 451-03-65/2024-03/200120 from 05/02/2024).

The Data

References

Burazer, N. (2023). Serbia. Nations in Transit. Freedom House.

CRTA (2024). Final Election Observation Report – 2023.

Jovanović, M. & Simić, S. (2023). Determining contextual factors of the 2022 snap elections in the Republic of Serbia. Politička revija, 77(3), 31–55.

Damnjanović, M. (2020). Serbia. Nations in Transit. Freedom House.

Government of Serbia (2023). Government sends to president proposal for disbanding parliament. Statements of government.

Pajvančić, M. & Marinković, T. (2022). Izbori 2022. godine pred Upravnim sudom-pregled postupanja i odluka. Belgrade: CEPRIS.

Pásztor, B. (2022). Nova izborna regulativa i princip reprezentativnosti: Zakon o izboru narodnih poslanka i Zakon o lokalnim izborima. Srpska Politička Misao, 75(1), 9–32.

Pavlović, D. (2024). Parliamentary and Local Elections in Serbia 2023. Contemporary Southeastern Europe,11(1), 1–11.

Schennach, S. et al. (2024). Observation of the early parliamentary elections in Serbia (17 December 2023). Election observation report. Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe.

Tanjug (2023, 30 October). Vlada predložila raspuštanje Skupštine i raspisivanje izbora. Tanjug.

OSCE/ODHIR (2024). Republic of Serbia. Early Parliamentary Elections. 17 December 2023. ODHIR Election Observation Mission Final Report. Warsaw: OSCE.

CESID (2023). Preliminary recommendations for improving the electoral process. Serbian general election, 17 December 2023.

Notes

- A 13-year-old boy committed a violent crime at an elementary school in Belgrade on May 3, resulting in the deaths of 8 pupils and the injuries of 6 children and a teacher. The following day, a 21-year-old man killed eight people and wounded 14 others in the villages of Malo Orašje and Dubona near Mladenovac.

- This designation is without prejudice to positions on status and is in line with UNSCR 1244 and the ICJ opinion Kosovo Declaration of Independence.

- It is a curiosity that Marko Milošević, grandson of Slobodan Milošević, who recently joined the party, was third on this list for the parliamentary elections.

- Resolution 2024/2521 (RSP).

- The Working Groupis composed of two representatives, of each parliamentary group in the National Assembly, every natioonal minority political party which does not have a parliamentary group in the National Assembly and civil society organisations and associations such as the CRTA.

citer l'article

Maja Nastić, Parliamentary election in Serbia, 17 December 2023, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue