Parliamentary election in Slovenia, 24 April 2022

Marko Lovec

Associate Professor at Ljubljana UniversityIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Marko Lovec

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

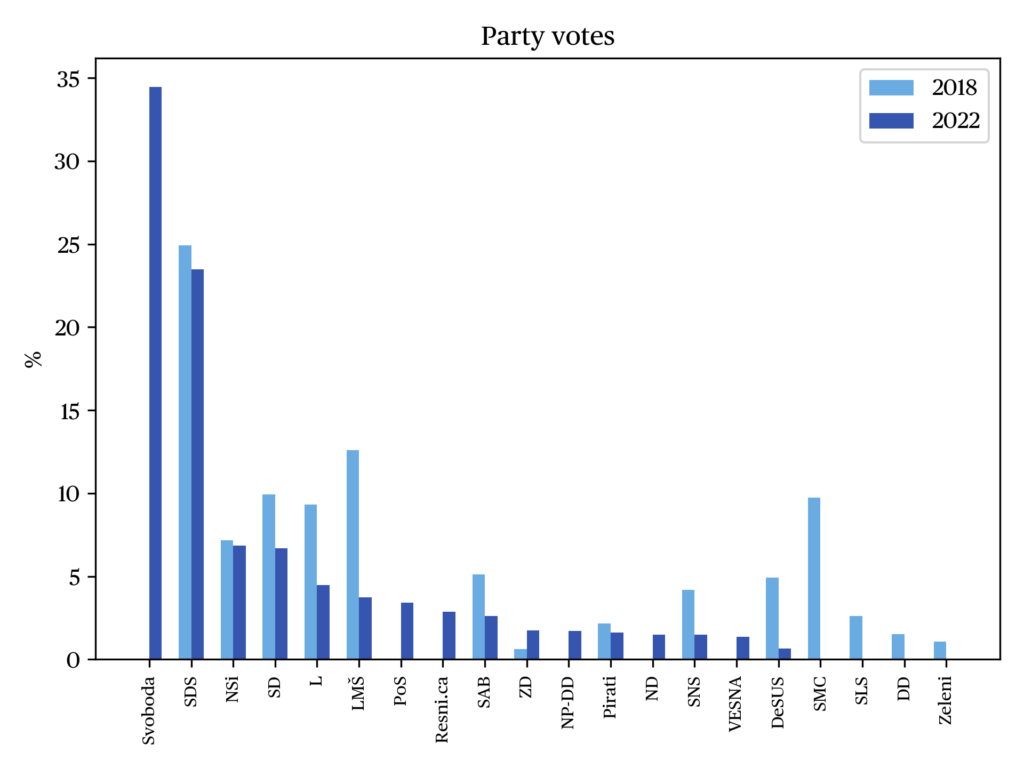

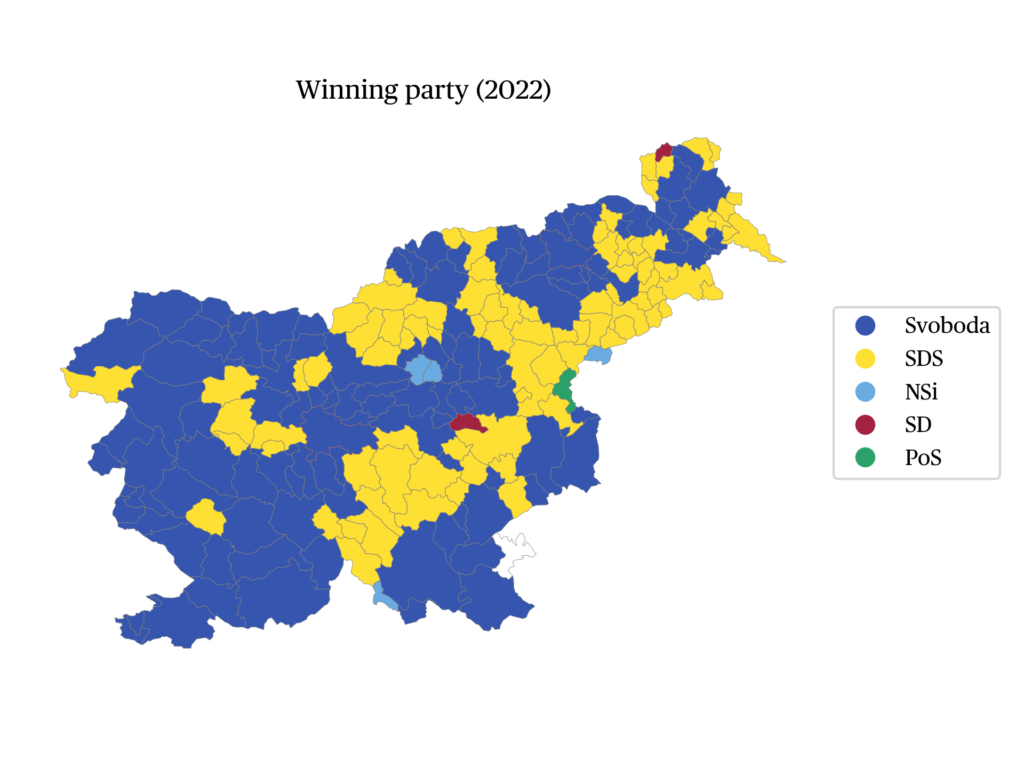

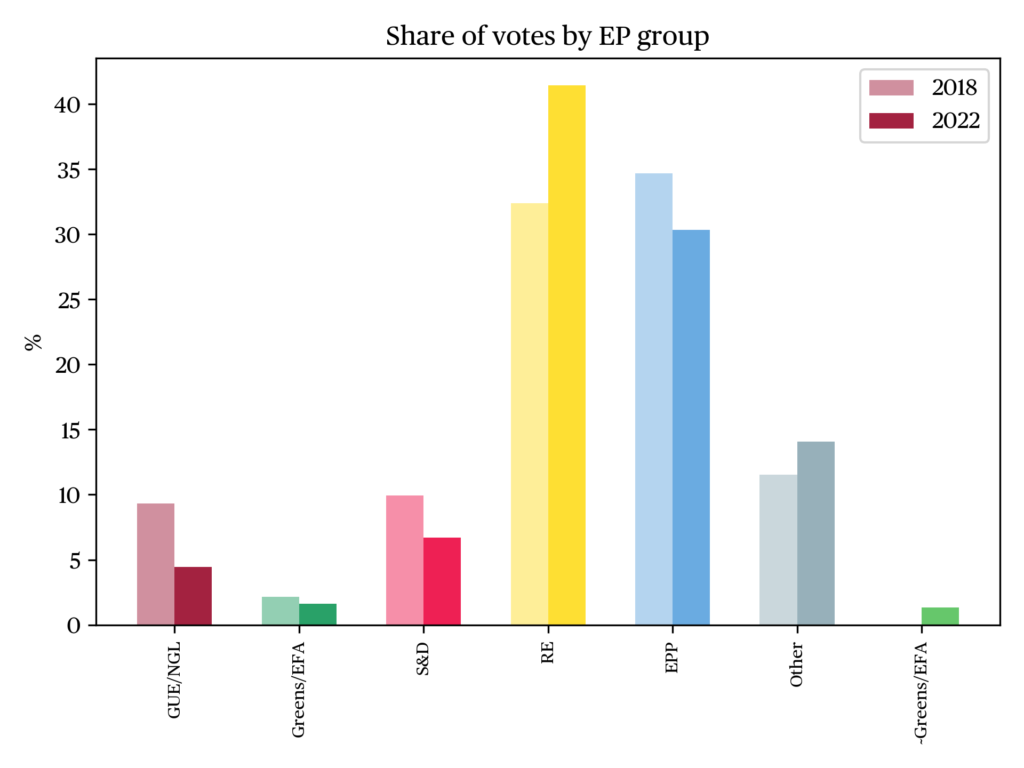

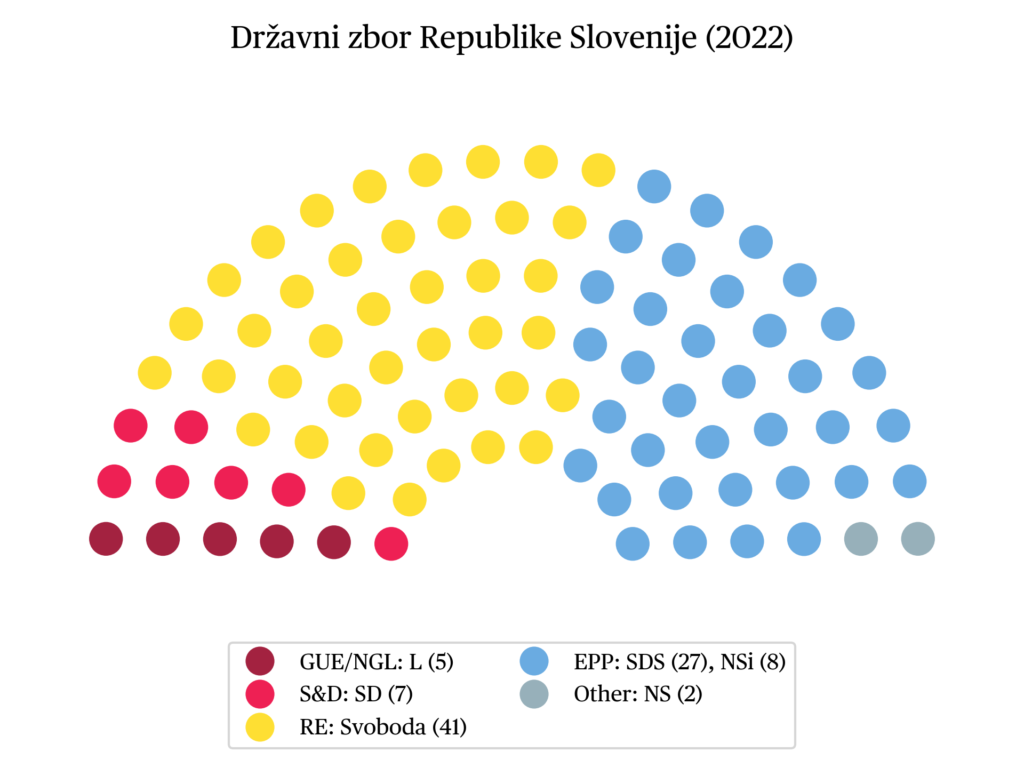

In Slovenia, parliamentary elections were held on 24 April 2022. These were the first regular parliamentary elections since 2008, a sign of a political turbulence in the country over the past 15 years. The elections were characterized by a high turnout of 70.79%, the highest since the new millennium. The Freedom movement (Freedom-RE) led by newcomer Robert Golob won the elections by 34.45% gaining 41 seats in the 90-seat parliament (two seats are reserved for elected representatives of the Italian and Hungarian national minorities). The relatively strong victory of a party that emerged just a couple of months before the elections came as a surprise. The Slovenian Democratic Party (SDS-EPP, nationalist-conservative) led by Prime Minister Janez Janša came second with 23.48% of votes (27 seats), followed by the government coalition partner of SDS, New Slovenia (NSi-EPP, Christian-liberal), with 6.86% (8 seats), the Social Democrats (SD-S&D) with 6.69% (7 seats) and The Left (Levica-GUE/NGL) with 4.46% (5 seats). The remaining of about 20 parties and lists which participated at the elections fell short of the 4% threshold. This included several parliamentary parties, namely the government coalition members Konkretno (former Modern Centre Party-SMC-RE) that joined the newly established list Let’s unite Slovenia (PoS), the Democratic pensioner’s party (DeSUS-E/RenewRE) and the Slovenian National Party (SNS, nationalist) which was not a formal coalition member but supported the government, as well as opposition parties Marjan Šarec’s List (LMŠ-RE) and Alenka Bratušek’s Party (SAB-RE). Elections were characterized by a strong mobilisation of especially centrist and non-traditional voters against Janša’s government. These criticized the incumbent’s alleged interference with independent state institutions and the restrictions it imposed during the pandemic, that were broadly seen as poorly communicated and disproportionate. The election was marked by tactical voting of especially centre-left voters, as a reaction to the fragmented and weak role of the centre-left opposition parties in the past.

Strong mobilisation against Janša’s SDS

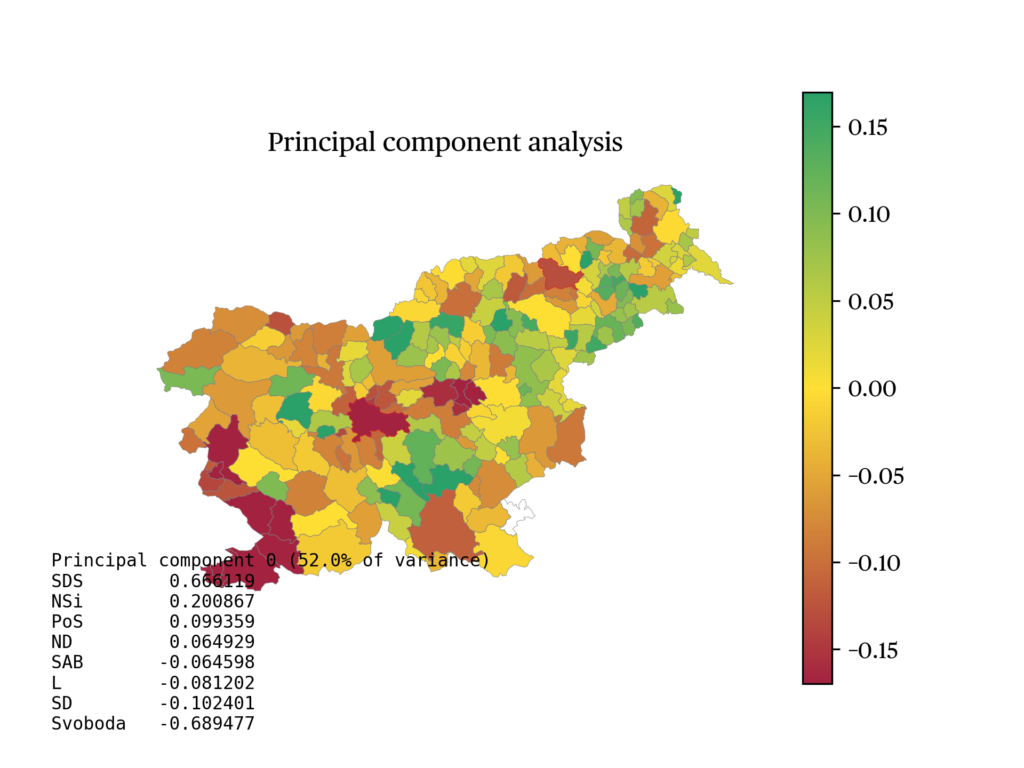

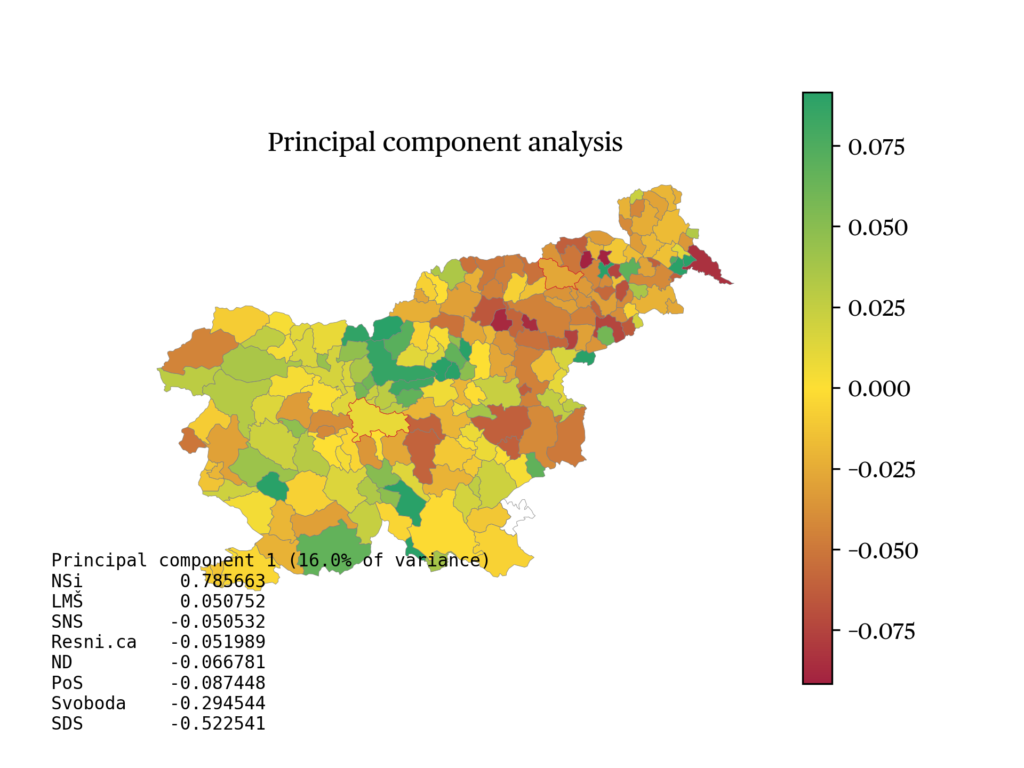

The coalition government led by Janša came to power in early 2020 after the fragmented center-left minority government coalition led by Šarec collapsed. Šarec’s government consisted of LMŠ, SD, SMC, SAB and DeSUS and was supported by Levica. In hope of snap elections, Šarec resigned. However, Janša managed to put together a center-right coalition, which consisted of SDS, NSi, SMC and DeSUS and was supported by SNS. Janša was successful in forming a coalition because, according to the polls, many MPs would likely lose their seats at the snap elections. Moreover, the start of the pandemic created a sense of an emergent need for an effective government. The support for the government was relatively high in the first months but soon plummeted due to allegations of corruption related with procurement of emergency medical supplies and restrictive measures that were often poorly communicated, disproportional and lacked proper legal basis. The government was also accused of using the pandemic as a cover for interfering with the independent state institutions, the media and civil society. Civil society organizations launched anti-government protests, which with some interruptions and against attempts to suppress those protests (including by overstepping police authorities), lasted throughout the government mandate. Janša was also criticized for allying with the Eurosceptic and illiberal forces internationally, especially with the regime of Viktor Orbán in Hungary which financially supported pro-Janša media outlets in Slovenia, and for controversial foreign policy actions, such as when Janša congratulated Donald Trump for winning the elections in the United States (which he lost) and waging rhetoric attacks against individual MEPs and European journalists. In the second part of the Slovenian presidency of the EU Council in 2021, Janša started to use more constructive rhetoric to present himself as a moderate and pro-European actor. When the war in Ukraine broke out in early 2022, at a time which coincided with the official start of the electoral campaign, Janša strongly condemned the attack and became one of the first Western leaders to travel to Kiev to gain positive coverage from Western media and regain international legitimacy. Janša’s government, in the backdrop of the pandemic and war in Ukraine, used expansionist fiscal policy that included subsidies distributed to large segments of the population such as tourist and energy vouchers, the latter handed out just two weeks before the election. SDS used two electoral slogans: »We Build Slovenia« and »No Experiments«. The former referred to several construction projects (cofunded by the EU) and the latter to the increasingly unstable international environment and to political contender Golob, who had little political experience. It also referred to some of the ideas of the center-left opposition, often painted as successors of the former communist regime, itself largely considered as a failed social experiment. Despite the increase of the total number of votes since the 2018 elections (279,897 vs 219,415), SDS obtained a lower share of votes (23.48 vs 24.92%) but gained more seats (+2) due to more parties failing to reach the threshold. SDS reached higher scores in areas with relatively lower voter density (ie. rural areas) and especially in the South-Eastern parts of Slovenia. In line with the principal component analysis of the vote, 54% of district-level variance can be explained by better performance of SDS in rural areas compared to urban areas and the Adriatic coast. Janša’s coalition partner NSi, led by Matej Tonin, had been in the shadows of the SDS due to SDS’s hegemonic role on the right side of the political spectrum, and did not distance itself sufficiently from some of the Janša’s most controversial moves; it also reached lower result compared to the 2018 elections (6.86% vs 7.16%). For the reasons explained above, NSi managed to gain one additional seat. NSi achieved better score in rural areas but to a lesser extent compared to SDS and, as opposed to SDS, achieved better scores in central and Western parts of the country. According to the principal component analysis, 16% of the variance can be explained by stronger NSi vote in the South-West of the country compared to the North-East. But the largest defeat for the government coalition and the center-right parties was that the rest of the SDS’s potential coalition partners fell short of entering the parliament. SMC, renamed Konkretno, led by Zdravko Počivalšek, which formed PoS together with several smaller non-parliamentary parties (Greens, Slovenian People’s party, New People’s party) was just below the threshold (3.41%) and lost 10 seats. Our country (ND) led by Aleksandra Pivec, a former minister in Janša’s government, was also below the threshold (1.5%) as was also the Slovenian National Party led by Zmago Jelinčič (1.49%) which lost 4 seats. Among the reasons for poor performance were competition between center-right parties such as between PoS and ND in the South-Eastern parts of Slovenia, failure to mobilize more voters, especially the ‘left behind’ voters (in parts of the rural areas where SDS, NSi, PoS and ND achieved better results, participation rates were often lower), and broad mobilization against Janša which went beyond the center-left and included right-wing and non-traditional voters. This was particularly evident in the case of the SNS voters; while Jelinčič supported Janša’s government, SNS voters were more pro-Russian and skeptical towards the Covid related restrictions. This was demonstrated by the relatively strong performance of the anti-covid-restrictions parties such as Resni.ca and NLLGZD (2.86 and 1.76% respectively).

A newcomer’s surprisingly high relative win due to tactical votes

The centre-left opposition parties — LMŠ, SD, SAB and Levica — faced criticism from their electorate due to their fragmented and weak role. Towards the end of 2020 they decided to work together more closely and established the Constitutional arch coalition (KUL), suggesting that acts of Janša’s government were a threat to the constitutionally guaranteed checks and balances and personal rights and freedoms. However, none of the parties managed to take a convincing lead in the polls to become the alternative to Janša’s predominance on the right. In the past 15 years, tactical and non-traditional voting of especially centre-left voters has taken extreme proportions in Slovenia, in a context of deconsolidation of the centre-left. Entirely new parties emerged and won the elections, only to be replaced by newer parties during subsequent elections. Thus, the Positive Slovenija of Zoran Janković won in 2011 (SAB was partially a successor of that party), the Modern Centre party led by Miro Cerar won the elections in 2014 (and was later renamed into SMC and Konkretno), and Šarec’s LMŠ came first among centre-left parties at the 2018 elections. Towards the end of 2021, Robert Golob, the former head of a state-controlled energy company, announced to run in the parliamentary election after Janša’s government did not extend his mandate. His Freedom movement was joined by individuals personally pressured by Janša’s government such as former judge Urška Klakočar Zupančič (new president of the parliament) or journalist Mojca Šetinc Pašek. In late 2021 and early 2022, polls demonstrated that Golob could challenge Janša’s relative victory at the elections. As a result, many centre-left voters shifted their support to Freedom. Freedom mainly focused on anti-government sentiments caused by interference with independent institutions and restrictions due to Covid, which enabled it to attract a broad range of voters. Despite his and his party’s limited political experience (Golob was previously associated with PS and SAB but did not play any major political role), throughout the campaign as well as last-minute allegations of Golob possessing an undeclared foreign bank account, Freedom won the elections with 34.45% of the vote and gained 41 seats. Freedom received 410,769, votes which is the single highest number achieved by any party in the history of Slovenia. Freedom reached top scores especially in the urban districts of the two largest cities in Slovenia — Ljubljana and Maribor — and the Western part of Slovenia next to the Italian border. This was to a large extent at the expense of the parliamentary centre-left opposition parties. A comparison with the opinion polls demonstrated that many of the centre-left voters decided to support Freedom in the weeks and even days before the election. Compared to the 2018 elections, SD went from 9.93% to 6.69% (-3 seats) and Levica from 9.33% to 4.46% (-4 seats). The more centrist LMŠ and SAB fell short of reaching the threshold (3.72 and 2,61%) and lost as much as 13 and 5 seats each. SD and Levica were particularly disappointed as they failed to mobilize some of their traditional voters, some of which even abstained from voting. They failed to make socioeconomic issues a central topic of the campaign, due to a predominant focus on more liberal topics such as interference with state institutions and liberties. SD also used slogans with ambiguous messages such as “Different” and “No promises.” Levica performed poorly outside urban areas. After the elections, Golob, despite a strong position that would require just 3-5 additional votes for an absolute majority in the parliament (national minority MPs traditionally support each government coalition) decided to form a broader centre-left coalition that ld involved SD and Levica. Individual members of LMŠ and SAB were also offered positions. This was done to compensate for the lack of experience and membership on the side of Freedom, to consolidate the centre-left and to prevent future opposition from the left. Two thirds of the parliamentarians were newly elected and over half of those were MPs of Freedom. Freedom also lacked experienced people for executive positions. Becoming part of the government kept the existing leadership of SD and Levica in position and prevented internal overhaul in these parties due to poor election result. SD president Tanja Fajon became new Minister of Foreign and European affairs. SD also nominated ministers for judiciary and economy. Levica nominatenominated ministers for solidarity, labour and culture. Presidents of LMŠ and SAB and former prime ministers, Šarec and Bratušek, became minister (of defense and secretary at the ministry of infrastructure. The lanned merger of Freedom with LMŠ and SAB consolidated liberal-social parties and provided Freedom with the necessary membership and network ahead of the autumn local and presidential elections. Freedom also gained 2 MEPs ahead of its entrance into Renew.

References

Fink Hafner, D. & Novak, M. (2021). Party Fragmentation, The proportional system and Democracy in Slovenia. Political studies review.

IDM and Renner Institute (2022, 21 April). Online panel discussion. Parliamentary elections in Slovenia.

Lovec, M. (2022). Slowenien. In Yearbook of European Integration. Nomos.

Politico (2022). Slovenia 2022 general election. Online.

State election commission (2022). Election to the national assembly 2022. Online.

Valicon (2022, 26 April). Skoraj polovica udeležencev je volila taktično. Online.

citer l'article

Marko Lovec, Parliamentary election in Slovenia, 24 April 2022, Oct 2022,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue