Parliamentary Election in the Netherlands, 17 March 2021

Simon Otjes

Assistant Professor, Leiden UniversityIssue

Issue #1Auteurs

Simon Otjes

21x29,7cm - 102 pages Issue #1, September 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe: December 2020 — May 2021

Introduction

In 2021, the Dutch voters elected the most fractionalized parliament in Dutch history. In this fractionalized landscape the centre-right coalition retained its majority. The coalition benefited from popular support for its corona policy and did not pay an electoral price for the child benefit scandal that caused the government to step down three months before the election. This article examines the paradoxical trends of voters flocking away from established parties to smaller newer ones on the one hand and voters flocking to the government parties on the other hand.

In this article, I will discuss the context of the elections, specifically the corona pandemic and the childcare benefit scandal. I will examine the results of the election for each of the parties and I will briefly discuss the ‘second half’ of the elections the formation of a new government and its likely effect for European integration.

Social and Political Context

The Dutch general election, like most elections in 2020 and 2021, took place in the context of the world-wide corona pandemic. In the Dutch context, there also was a specific scandal surrounding childcare benefits.

The pandemic

Since the start of the pandemic the trust in the Dutch government has increased strongly (Van der Meer et al. 2020). In December, the government had introduced a new lockdown to prevent the third wave and this lockdown quickly included a nine o’clock general curfew. In general, Dutch voters were supportive of the government’s measures to contain the spread of the disease. Specifically, this meant that the support for the Liberal Party (VVD, Renew) of Prime Minister Mark Rutte had increased strongly in the polls. The party therefore decided to hinge their campaign on the leadership of Mark Rutte.

Corona was a thick blanket that covered the campaign. It prevented parties from in-person campaigning, instead parties relied on earned and paid media. The three televised debates proved particularly decisive for the election results.

Corona also prevented other themes from taking centre stage in the political arena. Parties dutifully debated themes such as the climate, healthcare and immigration, but none of these themes really dominated the political debate, as the real question was who was trusted to steer the Netherlands out of the corona pandemic.

The Childcare benefit scandal

In January 2021, the Dutch government coalition of VVD, CDA (EPP), D66 (RE) and CU (EPP) had resigned over scandal surrounding childcare benefits. In the Netherlands, most families with children younger than four receive benefits to pay for childcare. In an overzealous attempt to fight fraud, the Dutch government had ruined thousands of families who had committed only minor infractions or who had outside of their knowledge had contracted fraudulent childcare companies. The government had specifically investigated families with dual nationalities (Otjes 2021a). Moreover, the government had consistently provided parliament with false or incomplete information when it had questioned them on the subject. The government had resigned before a parliamentary debate on a critical report of a parliamentary investigation committee on the subject. The result of this was that the issue was never strongly politicized.

The results

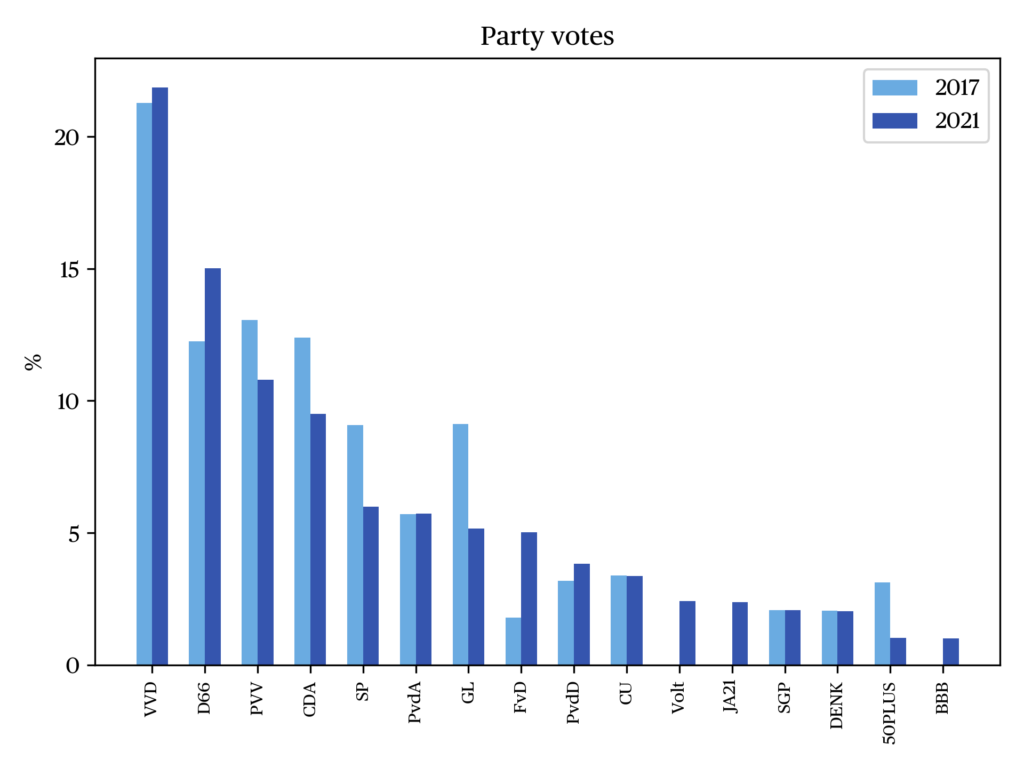

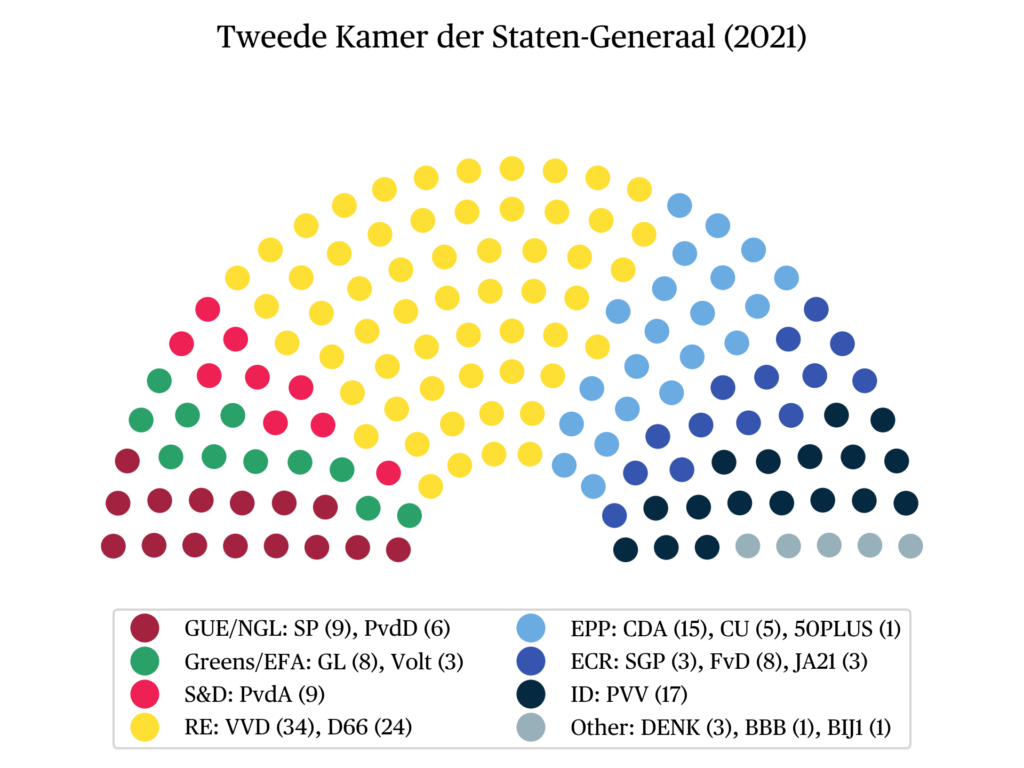

The elections resulted in a very fragmented parliament (see ‘Data’). No less than seventeen parties were elected into parliament, compared to 14 in the previous election. The largest of these (the ruling VVD) had only 34 out of 150 seats. This meant that also the effective number of parliamentary parties, a standard measure of fractionalization in political science (Laakso & Taagepera 1979), was quite high: 8.5 up from 8.1 in the previous term. This was 5.3 on average in the last 100 years. The Netherlands has extremely proportional electoral system where votes are almost perfectly translated into seats.

The elections saw relatively mild volatility: only 14% of seats changed hands. This was the lowest level of volatility in over twenty-five years. In particular the government parties were spared: usually government parties lose seats in the elections, now they retained their majority. It was the first time since the 2003 elections that the parties supporting the government kept their majority and the first time since the 1998 elections that they actually expanded their vote total. This effect was driven by the trust in Rutte as crisis manager and the fact that the most convincing bid to challenge his leadership came from D66, his own coalition partner.

Turnout was relatively high despite the Covid pandemic: 79% of Dutch voters turned out. The turnout was slightly lower than in 2017 (82%), but it was higher than the average turnout in the last twenty years. The government had attempted to boost turnout by allowing voters to vote in person for three days, by allowing people who are older than 70 to vote by mail and by allowing people to cast three proxy votes instead of two.

In order to understand the political landscape, the geographic trends and socio-demographic trends, it may be useful to follow the result per party. We discuss these in nine clusters: the VVD, D66 and the CDA are discussed separately, followed by the radical right (PVV, FVD, JA21), the traditional left (PvdA and SP), the new left (GL, PvdD and Volt), the small Christian parties (CU and SGP), parties rooted in migrant communities (Denk and Bij1) and parties representing specific communities (50PLUS and BBB). Unless specified otherwise, the demographic data reported below, comes from an exit poll by Ipsos (Harteveld & Van Heck 2021).

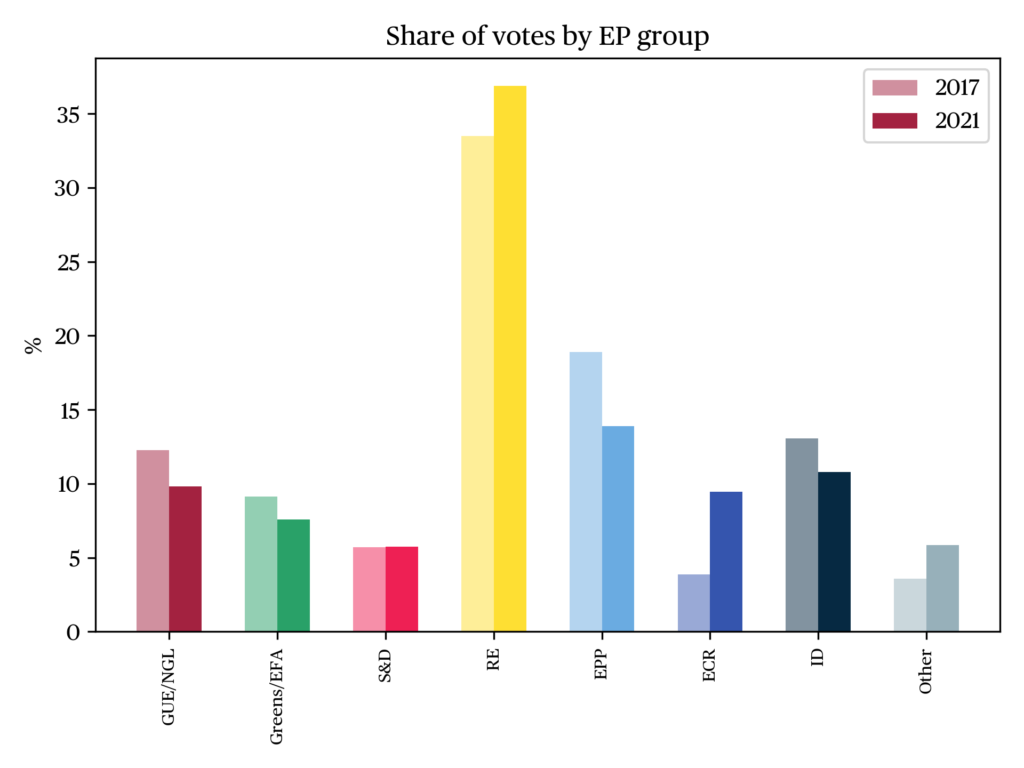

The liberal leader

For over ten years, the Liberal Party (VVD, Renew) of Prime Minister Mark Rutte had governed the country. The party can be characterized as ‘conservative liberal’ and stands on the right of the European liberal family. It favours market-solutions to economic problems. During the corona crisis, the party deviated from its fiscal conservatism, and instead it supported a massive program to keep Dutch workers employed and companies afloat in the economic crisis. On cultural matters it mixes conservative positions on immigration and law order with progressive positions on moral matters such as euthanasia and same-sex relationships. The party describes itself as ‘euro-realist’: it supports European integration when it benefits the Dutch interest, specifically the Dutch economy.

For over a year, the polls indicated that the VVD would expand its seat total in the upcoming election. In January the Poll of polls of the Peilingwijzer had indicated that nearly 30% of the Dutch voters would cast their vote for the VVD (Louwerse 2021). Rutte’s performance as manager of the corona crisis was lauded by voters and the announcing stricter measures to curb the disease had led to increases in support for him and his party. Polling clearly indicated that since the start of the corona-crisis, Rutte’s ratings among voters had increased strongly (Kanne & Driessen 2021). The result (22% of the votes) was considerably less than the party had polled in the months leading up to the election. Still the party retained its position as largest party.

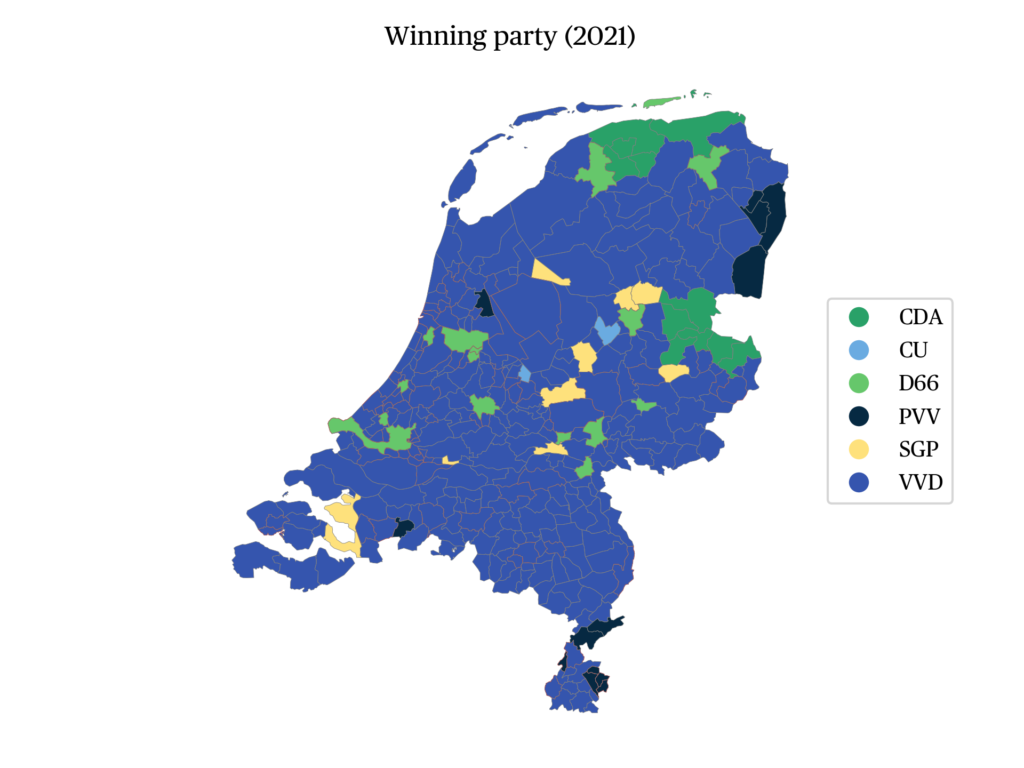

The VVD was the largest party in nearly every municipality and was particularly strong in larger cities and commuter towns in the three most populous provinces: North-Holland, South-Holland and North-Brabant. The party was the largest among men and women, in every age group and among voters at every level of education. It performed better among men, highly educated voters and middle-aged voters.

The liberal challenger

Democrats 66 (D66, Renew) which was also part of the governing coalition broke the ‘rule’ that had been true for 40 years that governing meant that the party would halve its seat total in the election. Instead the party expanded its vote total and became the second party with 16% of the seats. The party’s leader, the sitting minister of development cooperation and foreign trade, Sigrid Kaag (D66, Renew), performed particularly well in the debates. In January, the party had polled below 10% of the vote. Kaag was able to win the support of progressive voters with the promise of new leadership. The sitting minister positioned herself as the progressive alternative for Mark Rutte.

D66 is a social-liberal party which sits in the centre of the European liberal family. It supports strong action to fight climate change. It is fiercely pro-European. It is progressive on moral matters, such as women’s and LBGT+ emancipation. It mixes left-wing and right-wing positions on the economy, for instance advocating investment in education but also a more liberalized pension system. On corona-policy, D66 distanced itself somewhat from the government in particular in advocating more freedom for vaccinated people and ending the curfew. The party wants the Netherlands to embrace a multicultural and cosmopolitan identity. On the matter of national identity, Kaag had the strongest clash with Geert Wilders (PVV, I&D), who accused her of betraying the Netherlands by wearing a headscarf during a visit to Iran. Kaag confidently defended herself by claiming that she had acted in the national interest by visiting Iran and advocating for peace in the region.

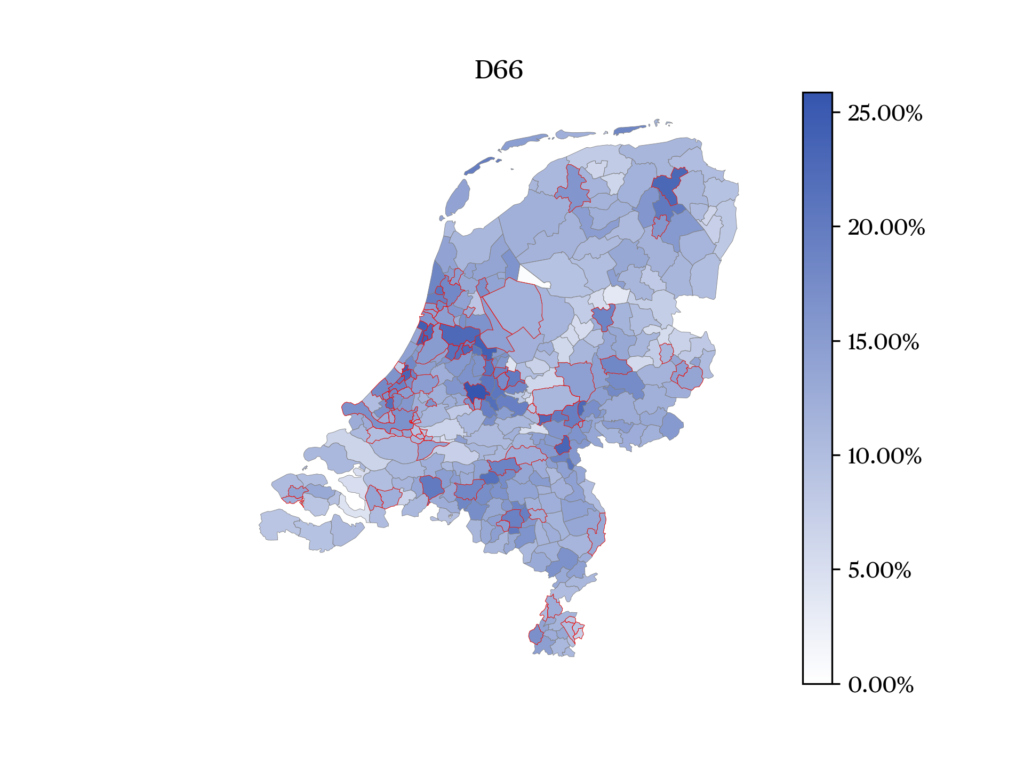

D66 performed particularly well in the largest cities: the party was the largest in Amsterdam, Rotterdam and The Hague. It also did well cities with universities, such as Wageningen, Leiden and Groningen. The party did best among higher educated voters, younger voters and women. The last is particularly notable because in 2017 (in contrast to 2021), D66 had a majority male electorate (NOS 2017). This is a clear indication that Kaag was able to court female voters with her bid to challenge Rutte’s leadership.

The Failed Christian-Democratic Challenge

The Christian-Democratic Appeal (CDA, EPP) was riddled with leadership problems. The party held an internal election to choose a new leader. Hugo de Jonge (CDA, EPP), the minister of healthcare responsible for corona-policy won that election. He stepped down less than half a year after being elected because he found it impossible to combine fighting corona with campaigning. He was replaced by Wopke Hoekstra (CDA, EPP), the minister of finance. He had chosen not run in the internal election. Hoekstra, the stern minister of finance, was seen as the ideal leader of the CDA, who could perhaps even replace Mark Rutte as Prime-Minister and make the CDA the largest party again. Both De Jonge and Hoekstra made a series of larger or smaller mistakes: for instance, De Jonge, who was responsible for corona-vaccination had chosen to start vaccinating much later than other countries to popular dissatisfaction. Hoekstra had taken the opportunity to ice skate in the famous ice-rink Thialf as part of the campaign, despite the fact that it was officially closed to the public. Hoekstra lost his popular appeal and the party went from 13% to 10% of the vote.

The CDA is ideologically similar to the VVD, right-wing on economic issues, conservative on matters of migration, pro-European where it serves the national interest. The only difference is that the party is more conservative on moral matters.

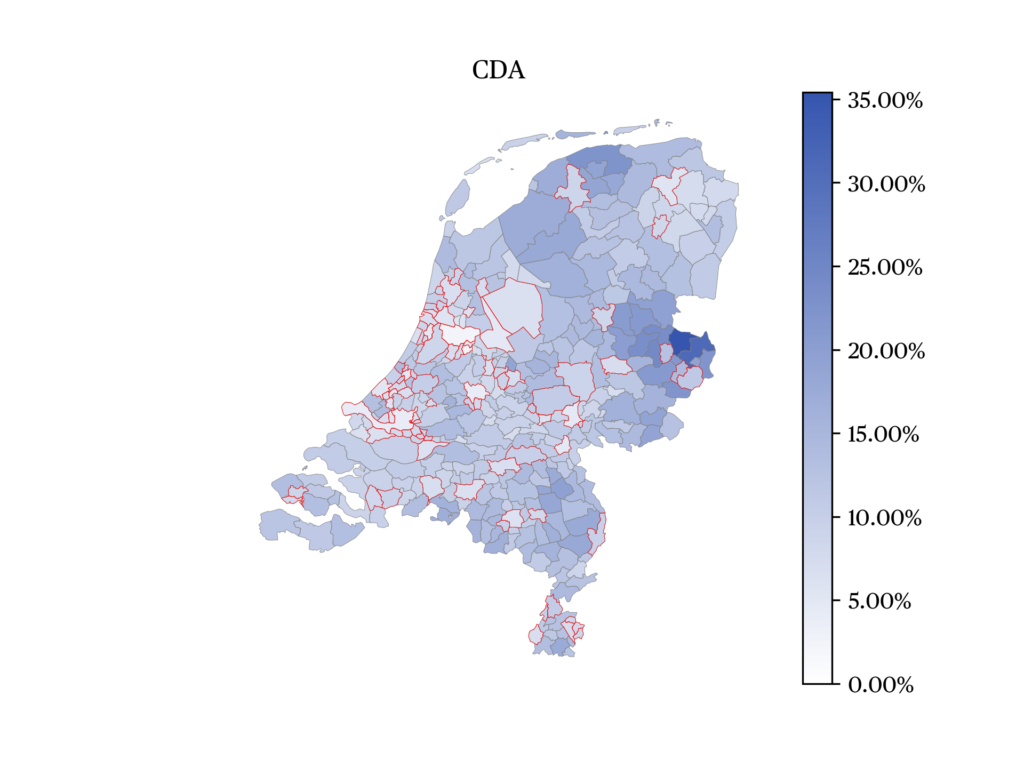

The CDA performed well in rural areas in the North and East of the country (Fryslân, Groningen and Overijssel). The party performed particularly well in Twente where the number 2 of the party, Pieter Omtzigt, the MP who fought for the interests of the victims of the child benefit scandal lives. The CDA performed well among voters who were aged fifty or older where it was the second largest party.

The Radical Right

In 2021, three radical right-wing populist parties entered parliament: the PVV, a main-stay of the radical right family, the FVD, which reinvented itself as anti-lockdown party and JA21, a relatively moderate branch of this family. Together these parties expanded their seat share from 15% to 19%, the highest for the populist right since 2002.

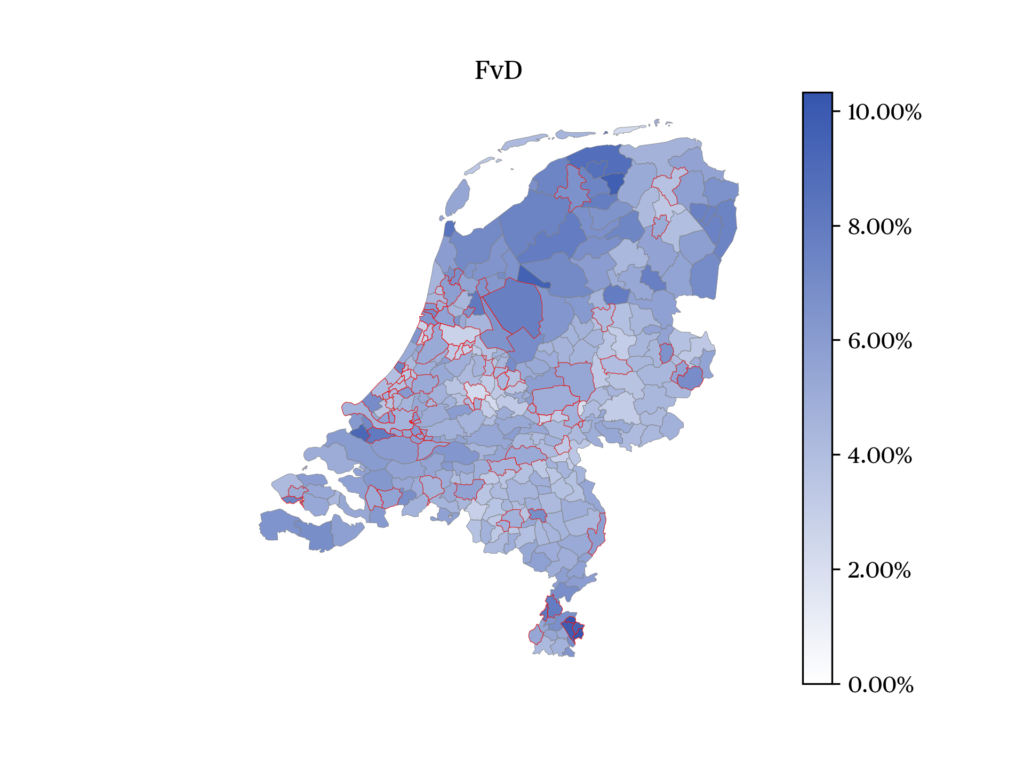

In 2017, Forum for Democracy (FVD, ECR) had entered parliament as hard-Eurosceptic party: it advocates the Dutch withdrawal from the EU. On other matters is a clearly radical right-wing populist party with a neo-liberal bent. It has right-wing positions on immigration, the environment and the economy. In 2019, it did well in the European and Provincial elections. After that the decline set in. Its youth wing had attracted more extremist elements: in their WhatsApp-groups, young members shared anti-Semitic memes. This was the reason for a split in the party in November 2020. The remaining, radical wing of the party led by Thierry Baudet reinvented itself as an anti-lockdown party. FVD was the only party to hold in-person campaign events. In these events, Baudet openly shared his skepticism about the dangers of the corona virus and his opposition to vaccination. This allowed the party to make a resurgence: in January 2021, the party was polled at two percent of the vote but it won five percent.

The moderate wing of the FVD formed Correct Answer 2021 (JA21, ECR), which also entered parliament. JA21 is a radical right-wing populist party but it is more moderate compared to PVV and FVD: it wants to limit immigration but does not want to close down mosques. It is Eurosceptic but does not want the Netherlands to leave the EU. It believes that humans cause climate change but thinks the Netherlands can better adapt to the coming change than try to prevent it. It does not deny the severity of corona. It is moderately conservative on moral matters and right-wing on economic matters.

The Freedom Party (PVV, I&D) of Geert Wilders remained the largest radical right-wing populist party in the Netherlands. The party focuses strongly on immigration, civic integration, national identity and Islam, which it sees as a dangerous ideology and not as religion. The party wants do defend the rights of women, gays and lesbians against what it perceives as the threat of Islam. The party denies the need to take government action to fight climate change. It wants the Netherlands to leave the European Union. On economic issues, it is mixes left and right-wing positions on economic issues for instance proposing to lower the pension age to 65, which mostly benefits Dutch people without a migration background, while proposing more stringent measures for welfare, which relatively many people with a migration background rely on (Otjes 2019).

The PVV was generally supportive of the government’s action to fight corona although it did call for the end of the curfew and the opening of outdoor dining and drinking. The PVV saw a relatively small loss of (from 13 to 11%). This was the end of a roller coaster ride in the polls: in the 2019 European election, the PVV had even lost its seats in the European Parliament. As the FVD lost support, the PVV recuperated.

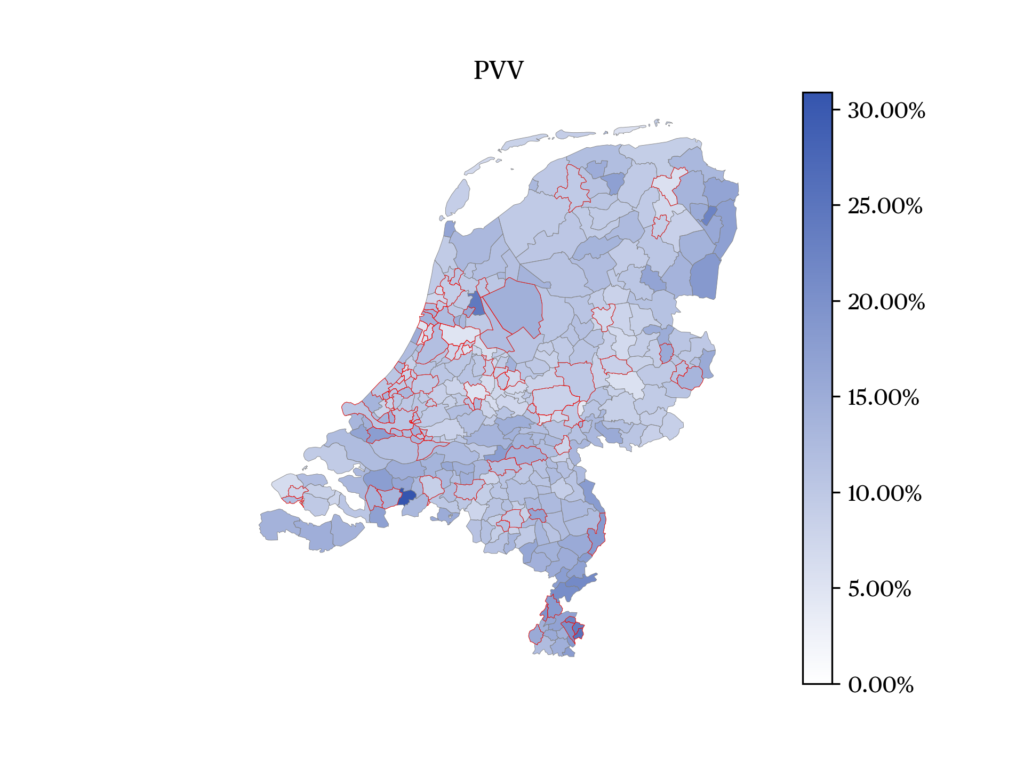

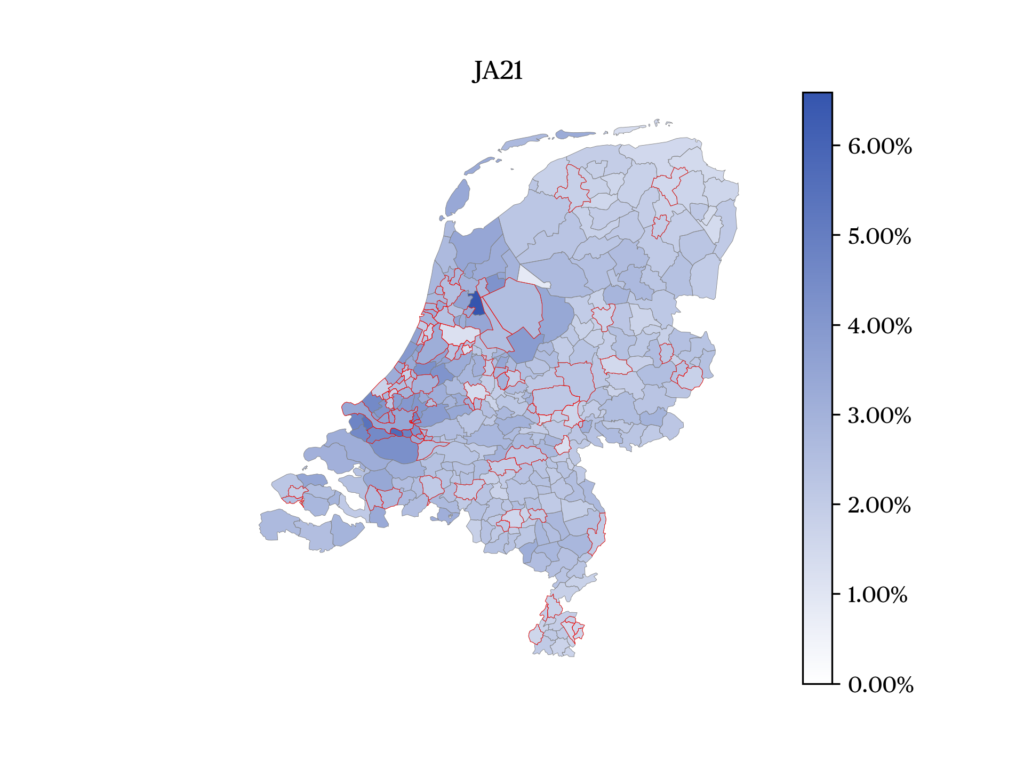

The PVV, FVD and JA21 appeal to a similar electorate but with some differences (Spierings et al. 2021). All parties appeal to men and voters who do not trust the government, but the PVV electorate is much older than the JA21 and FVD electorate. Where it comes to education the most interesting segmentation occurs: the PVV attracts voters with the lowest level of education, the FVD does best among voters with medium levels of education and JA21 does best among voters with the highest level of education. There also are geographic differences: The PVV performed well in peripheral municipalities in the Limburg (where Geert Wilders originates from), North-Brabant, Groningen and Drenthe. Citizens here often feel that the Dutch government focuses too much on the West of the country and not enough on their interest. The FVD received most support in these peripheral areas in Fryslân and Limburg, but also in commuter towns in the West of the country. JA21 finally did well in commuter towns close to Amsterdam and Rotterdam.

The Traditional Left

The Labour Party and the SP had their traditional base in the working class. These parties are in decline. They won only 12% of the seats, compared to 15% in 2017 and 35% in 2012.

For practically all of its existence, the Labour Party (PvdA, S&D) had been one of the two largest parties in parliament. In 2017 the party lost more than three quarters of its seats. It is a social-democratic party with centre-left positions on immigration, the economy, moral and cultural matters, EU integration and the environment. It was generally supportive of the government’s anti-corona measures. Like the CDA, it also suffered leadership problems. The party’s leader, Lodewijk Asscher stepped down three months before the election. As minister in the 2012-2017 Rutte II cabinet, he was partially responsible for the child benefit scandal that had caused the fall of the Rutte III cabinet. He was replaced by the relatively unknown former minister of development cooperation and foreign trade, Liliane Ploumen. The poor performance of the Dutch Labour Party fits a larger trend in Europe where social-democratic parties are under pressure (Benedetto et al. 2020). The fact that for a segment of traditionally social-democratic voters the social-liberal party D66 was an appealing alternative also fits more general European patterns (Abou-Chadi & Hix 2021).

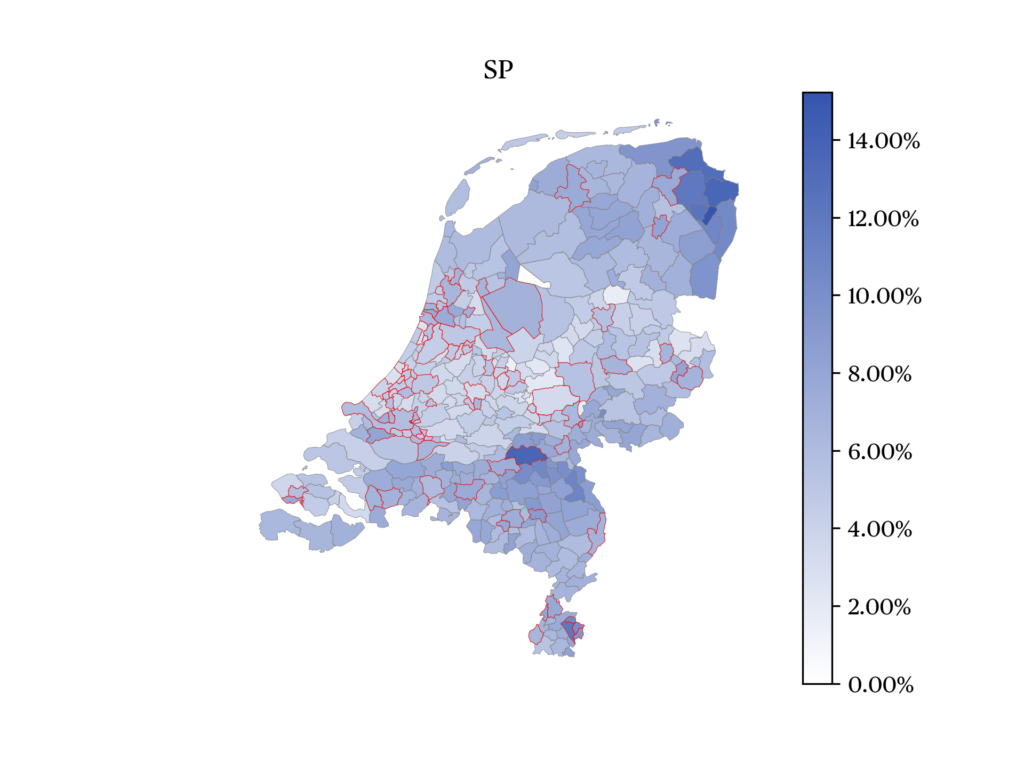

The Socialist Party (SP, GUE/NGL) is a radical left-wing party. The party advocates for more government intervention in the economy to ensure a more equal distribution of income. It wants the Netherlands to house more refugees (although not more labour migrants). It is Eurosceptic (although it does not advocate the Netherlands leaving the EU). It is generally progressive on moral matters (although skeptical about extending euthanasia) and it wants strong action to fight climate change (although it does not want poor citizens to pay for these measure). The SP was generally supportive of the government’s corona measures: this fit the profile of a party that traditionally advocates the interests of healthcare professionals, seniors and the chronically ill.The Labour Party kept the 6% of the seats the party had had. This was un expected result as the 6% had been seen previously as aberration due to the participation in the second cabinet Rutte. The SP lost almost half of its seats. The party blamed this on the fact it usually campaigns door-to-door in working class neighborhoods. This was not possible due to corona. It also possible that because it had been quite supportive of the government in the last year, its traditional base of lower educated voters that distrust the government no longer felt represented by them.

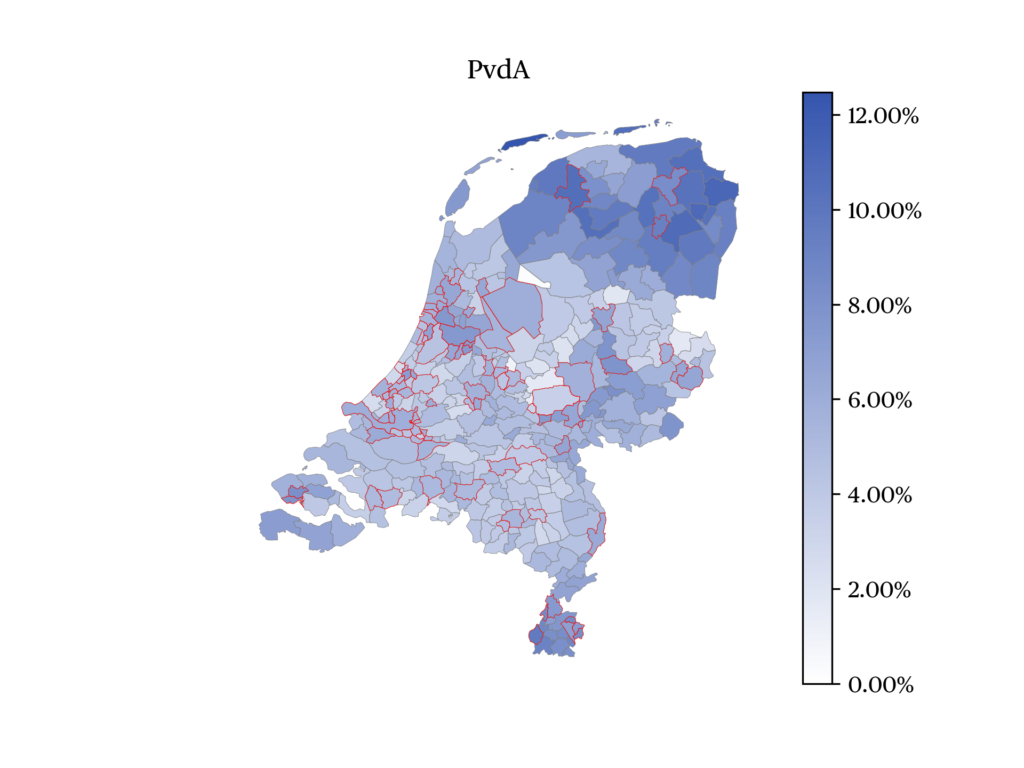

The PvdA performed well in the three Northern provinces (Fryslân, Groningen and Drenthe), the traditional heartland of the party and the South of Limburg (where Ploumen was from). The SP also performed well in more peripheral municipalities in Groningen and Limburg as well as in North-Brabant. Both were strongly supported by senior citizens. The SP did best among lower and middle educated voters, while the PvdA did best among higher educated voters, reflecting that the party had lost its traditional working-class base.

The New Left

In addition to the traditional left-wing parties, there also are three parties on the left with a more progressive and post-materialist orientation: the GreenLeft (GroenLinks), the Party for the Animals and Volt.

Four years ago, the party GroenLinks (GL, Greens/EFA), benefitting from the heavy loss of the Labour Party, it had performed particularly well. Now it lost almost all of its seats. This party focused its campaign on climate, hoping to make the elections climate elections. It has generally left-wing positions on the climate, the economy, immigration, moral and cultural matters. The party supports further EU integration. It also supported the government’s anti-Corona measures, although it did advocate for re-opening universities. In the last four years, it had developed an ambiguous relationship with the government, supporting it on crucial matters (the budget, climate policy and pension reform) but also being heavily critical of its tax policies. The party’s leader Jesse Klaver (GL, G/EFA) had attempted to build a left-wing alliance with SP, PvdA and D66. When these parties rebuffed this attempt publicly, the party had lost its credibility as ‘leader of the left’.

The deeply green Party for the Animals (PvdD, GUE/NGL) is more than a single-issue animal advocacy party. It focuses on animals, climate and the environment but takes left-wing positions on moral, cultural and economic matters. The party is moderately Eurosceptic, making it a good fit with the radical left instead of the Greens in the European Parliament. It also opposed the corona measures where they infringed civil liberties, in particular the curfew. More than anything the party is characterized by its opposition to what it calls ‘compromism’, the way of doing politics in the Netherlands where the process of finding consensus is more important than the long-term impacts of the decisions on people, animals and the environment. The party expanded its seat share from 3 to 4%.

The new party Volt (G/EFA) is part of the pan-European euro-federalist party Volt, which also has a German representative in the European Parliament. He sits in the Group of the Greens. In its first election, the 2019 European election, it performed quite well for a new party but narrowly did not win a seat. The party is close to D66 programmatically: progressive on moral and cultural matters, pro-European and centrist on the economy. The only real substantive difference is that Volt favours nuclear energy to avoid the climate crisis.

All three parties see a large share of their support concentrated in large cities with universities such as Amsterdam, Utrecht, Leiden and Nijmegen. All three perform best among higher educated voters and voters aged 34 and younger. In these municipalities and voting groups they see strong competition from D66. The GreenLeft lost almost half of its seats, because in the eyes of many voters D66 had a more credible claim that a vote for them would steer the formation in a progressive direction.

Small Christian parties

There are two parties who are supported mainly by protestant voters: the CU and the SGP.

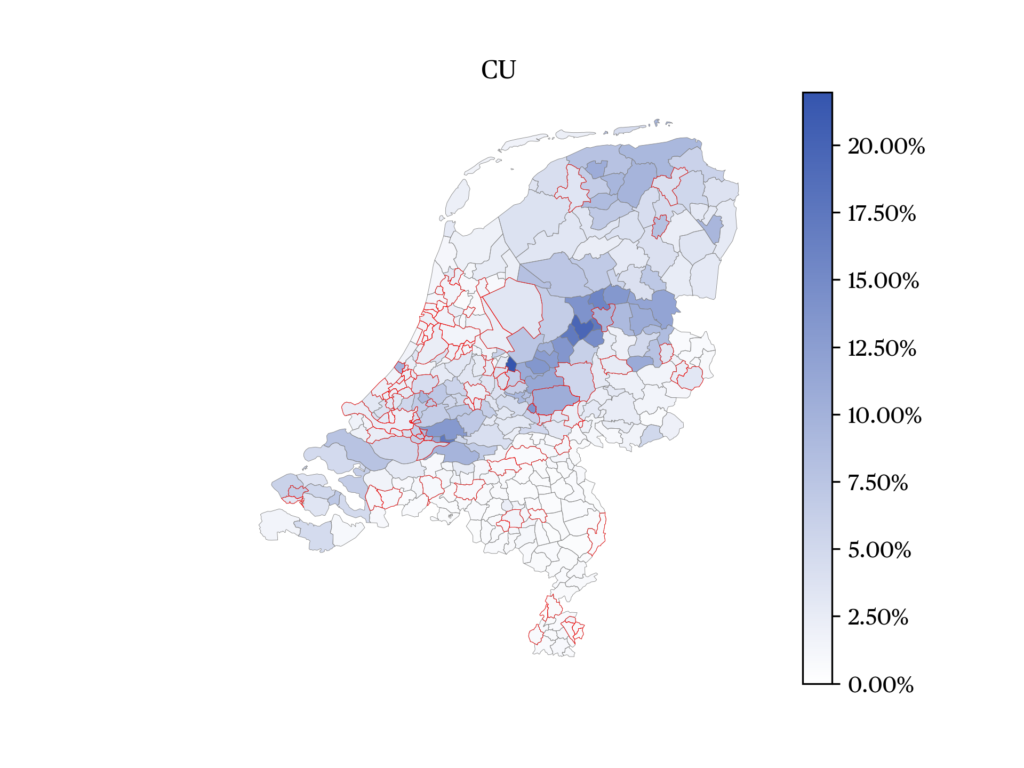

The ChristianUnion (CU, EPP) was the fourth government party. This small Christian social party mixes left-wing positions on immigration, economic matters and the environment with more conservative positions on moral matters, civic integration and EU integration. It broke with the conservatives in the ECR in 2019 because the allowed the FVD to join their group.

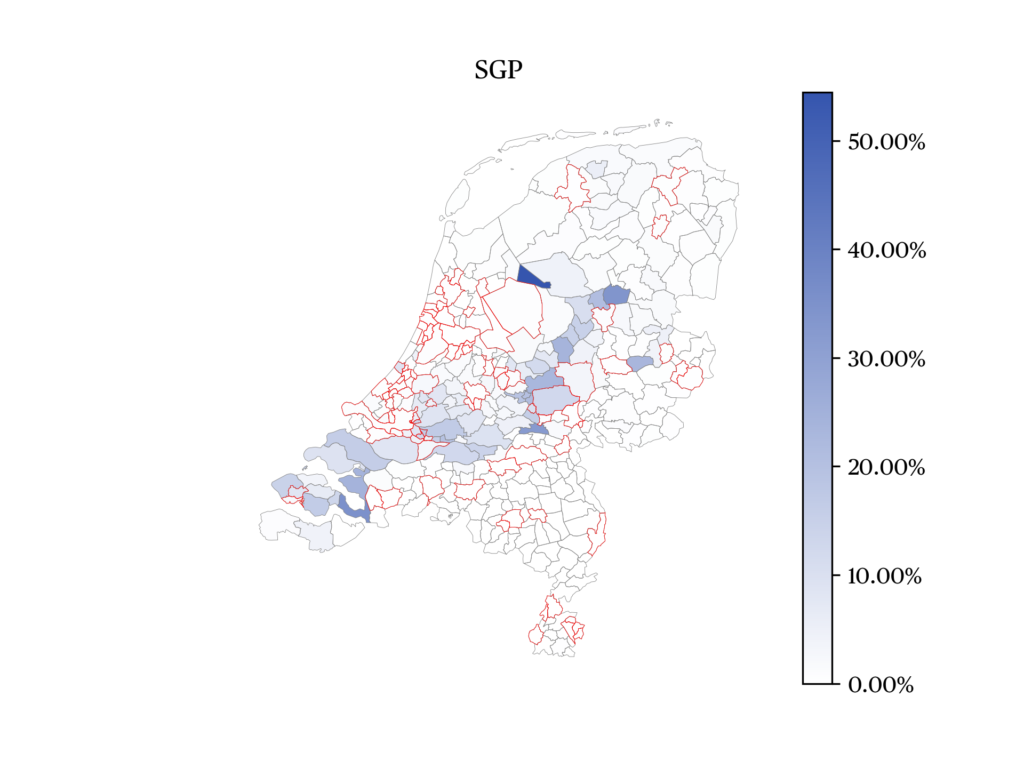

The Political Reformed Party (SGP, ECR) is the second small protestant party in the Netherlands. It is consistently a right-wing party on immigration, moral matters, the environment and the economy. The party is also moderately Eurosceptic. It opposed corona measures where they infringed on civil liberties, in particular the curfew.

Both parties have a consistent base of church going protestants who live in the Dutch Bible Belt, the Bijbelgordel, which runs from Zeeland in the South West to Overijssel in the North East. The CU was the largest in Bunschoten and Oldebroek, municipalities in this belt. The SGP was the strongest in a number of municipalities such as Tholen in Zeeland and Staphorst in Overijssel. Both are very stable, keeping their 3% and 2% of the vote.

Parties rooted in migrant communities

There are two additional parties on the left, which are rooted in specific migrant communities: Denk and As1 (Bij1).

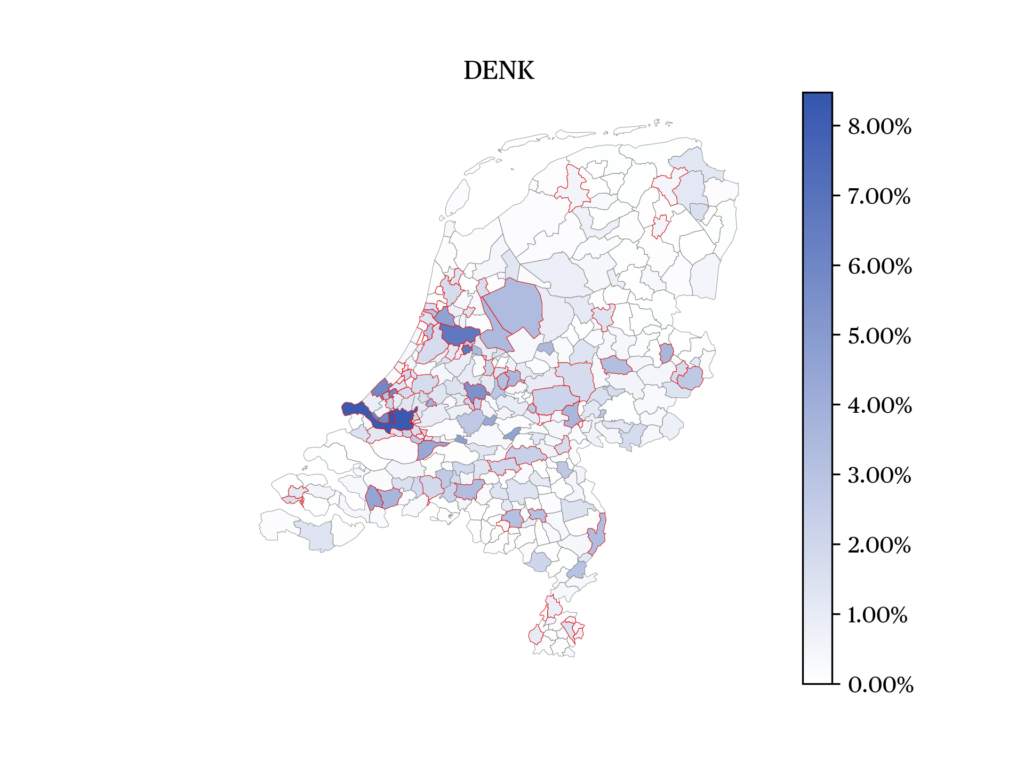

Denk is a party of, for and by citizens with a bicultural background. It performs particularly well among citizens with a Dutch-Turkish and a Dutch-Moroccan background and Islamic Dutch citizens (Otjes & Spierings 2021). The party was founded in 2015 as a split from the Labour Party and stays close to this party on economic and environmental matters. On cultural matters, such as immigration and the fight against discrimination, the party is progressive, while it is more conservative on moral matters. The party kept 2% of the Dutch votes.

As1 (Bij1) is a party that bases itself on the insights of intersectional feminism that there are different sources of oppression and disadvantage that can reinforce each other in different ways. These include race, gender, class and handicaps. This makes the party an anti-racist, anti-capitalist, feminist party. It is left-wing on immigration, moral matters, economic matters, the environment and the EU. It was the only party to criticize the government that its anti-corona measures were too lax. The party which was formed in 2016 as a split from Denk, which in the eyes of the party’s founder TV-presenter turned anti-racism campaigner Sylvana Simons was too conservative. Attention to the issue of racism was heightened after the murder of George Floyd and the anti-police violence protests in the US and Europe. The party became an assembly place for those who felt that GL was too right-wing on economic matters and the SP too conservative on cultural matters. The party received moderate support for migrant communities in particular from Dutch-Surinamese and Dutch-Antilleans and some support from progressive voters without a migration background (Otjes & Spierings 2021). This was enough for one seat.

Sectional interest parties

Finally, there are two parties that represent specific sector interests: seniors (50PLUS) and people living in rural communities (BBB).

50PLUS (EPP) is the Dutch pensioners’ party. In general, the party advocates for the interests of seniors. It is progressive on moral matters and more conservative on the environment, EU integration and immigration. The party saw major internal conflict with its party leader leaving to form his own (unsuccessful) party and its new leader breaking with the party’s commitment to lowering the retirement age. Its sole MEP which sat in the EPP also left the party. Due to these conflicts the party lost all but one of its seats. The remaining support came almost exclusively from people older than fifty.

The Farmer-Citizens’ Movement (BBB) is a new party that advocates the interests of Dutch people in rural areas in particular farmers. Its success can only be understood with reference to the huge resistance by farmers against proposals to reduce nitrogen pollution (such as cutting half the number of cattle in the Netherlands). While these protests were mostly in 2019 farmers were still dissatisfied with government plans. It is notable that three of the four current government parties (VVD, CDA and CU) usually performed well among farmers. A new party for rural Netherlands was formed. This party is moderately right-wing on environmental, cultural and economic matters, it is Eurosceptic and more progressive on moral matters. The party won one seat in parliament. Its support was concentrated in rural areas in particular in the East of the Netherlands, where party’s top candidate Caroline van der Plas was from.

Government Formation

The process of cabinet formation is perhaps more important than the election in determining policy outcomes. Some have even called it the “Bermuda Triangle of Dutch politics”, where the election result disappears and something unexpected can come out (Van Keken and Kuijpers, 2021). While it was clear from the on-set that the formation process would be complex, it became more byzantine in the first two weeks.

The formation took a dramatic turn when became public that the scouts (Annemarie Jorritsma (VVD) and Kajsa Ollongren (D66)) had discussed the political future of Pieter Omtzigt, the CDA MP who had been instrumental in exposing the child benefit scandal, with Mark Rutte. This led to a motion of no confidence against Rutte supported by the entire opposition. In the subsequent weeks minutes of cabinet meetings were leaked which indicated that the lack of information provided to parliament was the result of a conscious political choice. The formation process effectively halted. Two successive informateurs have since been appointed, veteran negotiator Herman Tjeenk Willink and the Chair of the Social-Economic Council, Mariëtte Hamer At the moment of writing (8/6/2021), it is unclear what this way out will be. The only thing that seems very likely is that the two largest parties VVD and D66 will form the basis for the new coalition.

European perspective

Also, where it comes to the EU, the government formation will be more important than the elections. The EU was not seriously debated in the campaign (Boekestijn et al. 2021). Yet, the new government faces serious choices. The Rutte III government opposed steps towards European economic policy integration, such as Eurobonds and permanent economic stabilization mechanisms (Otjes 2021b). The presence of the Euro-federalist D66 at the government table did not mollify the government’s position. Its three current coalition partners, all Euro-realist parties, set the agenda. It looks likely as though the Liberal Party and D66 will form the core of this new government. EU policy will mostly be determined by the interplay between VVD and D66 and their prospective government partners. Mark Rutte of the Euro-pragmatist and fiscally conservative VVD enjoys a reputation as “Mr. No” in Brussels (Van Wiel 2020): he will want continue being a brake on anything resembling a transfer union. The good result of the radical right is likely to put electoral pressure on the Liberals to stay their course. D66 however will want to chart a much different course, both in substance and tone. The entry of Volt into the parliament may force them to realise their pro-European promises (Otjes 2021b).

Conclusion

All in all, these elections reflect the specific national and global circumstances in which they took place: the corona pandemic help explain some of the general patterns, but for the specific parties, events like the child benefit scandal, the murder of George Floyd or the nitrogen crisis mattered. These events help explain the contradicting patterns of increasing movement towards smaller parties and towards government parties.

The elections in the Netherlands are only the first half of the expression of a political will. Crucial now is the formation of a new government. Given the global pandemic and its impact of the economy, the Netherlands wants to have a stable government. Forming a stable government will be challenge however given that the childcare benefit scandal has rocked the faith in Mark Rutte and his ability to lead a new government in many of the opposition parties.

Bibliography

Abou Chadi, T. and Hix, S. (2021). Brahmin Left versus Merchant Right? Education, class, multiparty competition, and redistribution in Western Europe. The British Journal of Sociology, 72(1), pp. 79-92.

Benedetto, G., Hix, S. and Mastrorocco, N. (2020). The rise and fall of social democracy, 1918–2017. American Political Science Review, 114(3), pp. 928-939.

Boekestijn, A.-J., Livestro, J., Schoonis, J., Segers, M. and De Vries, C. (2021, 22 March). Den Haag moet niet doen alsof er geen EU is. NRC Handelsblad. En ligne.

Harryvan, A.G. and Van der Harst, J. (2015). Succes creëert nieuwe verhoudingen: het Nederlands regeringsbeleid en de Europese integratie. in Vollaard, H., Van der Harst, J. and Voerman, G. (Eds.) Van Aanvallen! naar Verdedigen? De opstelling van Nederland ten Aanzien van de Europese integratie, 1945-2015. Amsterdam: Boom.

Harteveld, E. and S. van Heck (2021, 24 March). Onderzoek nu zelf de kiezersstromen: wisselvallig maar voorspelbaar. Stuk Rood Vlees. Online.

Kanne, P. and Driessen, M. (2021) I&O-zetelpeiling: Kelderend vertrouwen in Rutte raakt VVD niet. Online.

Laakso, M. and Taagepera, R. (1979). “Effective” number of parties: a measure with application to West Europe. Comparative Political Studies, 12(1), pp. 3-27.

Louwerse, T. (2021). Peilingwijzer. Online.

NOS (2017). Tweede Kamerverkiezingen 2021. Online.

Otjes, S. (2019). What is left of the radical right? The economic agenda of the Dutch Freedom Party 2006-2017. Politics of the Low Countries 1(2).

Otjes, S. (2021a, 22 January). The Dutch government has been rocked by scandal. Why does its leader remain untainted? Online.

Otjes, S. (2021b). The EU Elephant: Europe in the 2021 Dutch General Elections. Intereconomics.

Otjes, S. and Spierings, N. (2021, 22 March). Verdeeld succes migrantenpartijen. Stuk Rood Vlees. Online.

Spierings, N., Lubbers, M and Sipma, T. (2021, 25 March). PVV, Forum en JA21 maken samen radicaal-rechts groter. Sociale Vraagstukken. Online.

Van Keken, K. and Kuijpers, D. (2021, 10 March). Teruggebracht tot tweestrijd. De Groene Amsterdammer. Online.

Van der Meer, T., Van Steenvoorden, E. and Ouattara, E. (2020). Covid19 en de Rally rond de Nederlandse Vlag. Vertrouwen in de politiek en angst voor besmetting ten tijde van de eerste golf (maart-mei 2020). Coronapapers. Online.

Van Wiel, C. (2020, 22 June). Nu de Britten weg zijn, is Rutte Mr. No. NRC Handelsblad. Online.

The Data

citer l'article

Simon Otjes, Parliamentary Election in the Netherlands, 17 March 2021, Sep 2021, 52-60.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue