Presidential and parliamentary elections in Lithuania, May and October 2024

Issue

Issue #5Auteurs

Mažvydas Jastramskis , Ainė Ramonaitė

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

2024 was an election year in Lithuania. Citizens had the opportunity to vote up to five times. The elections included the first round of the presidential election on May 12, the second round on May 26, the European Parliament election on June 9, the first round of the parliamentary election on October 13, and the second round on October 27.

The presidential elections in Lithuania follow a two-round majoritarian system. If no candidate secures at least 50% plus one vote in the first round, the two candidates with the most votes advance to a second round, where a simple absolute majority determines the winner. One obstacle to candidate registration is requirement of 20,000 signatures, which represent about 0.83% of the voting-age population.

In the parliamentary elections, Lithuania employs mixed-parallel electoral system. Almost half of the Members of Parliament (MPs) – 70 out of 141– are elected through a proportional system (PR tier) in a nationwide district with a 5% threshold for political parties and 7 % for coalitions. For a PR tier, a flexible list system is used where each voter can cast up to five preferential votes. The remaining 71 MPs are elected in single-member districts (SMDs) through a two-round system. Under the Electoral Code adopted in 2022, the winner of an election no longer needs an absolute majority, as was the case before: in a single-mandate election, the candidate who wins the most votes is elected, but only if the candidate wins at least 20% of the total number of registered voters (which is quite rare given the traditionally low turnout rate in Lithuania). If no candidate receives at least 20% of the registered votes in a particular SMD, the top two candidates advance to the second round, where a simple majority determines the winner. While only political parties can present lists in the PR tier, independent candidates are allowed to run in SMDs.

Background

The minimum winning centre-right coalition, consisting of the Homeland Union–Lithuanian Christian Democrats (TS-LKD, EPP), the Liberal Movement (LS, Renew Europe), and the Freedom Party (LP, Renew Europe), has remained in place since the 2020 parliamentary elections. The government, led by Prime Minister Ingrida Šimonytė (TS-LKD), navigated tumultuous times marked by the COVID-19 pandemic, a crisis of illegal migration through the border with Belarus, Russia’s war on Ukraine (which brought an influx of Ukrainian refugees and heightened concerns over the national security), and a surge in inflation. While these crises were managed (with varying degrees of efficiency), they contributed to a political atmosphere of growing polarization and societal discontent. Notably, this led to a wave of anti-pandemic measure protests in 2021 and was also reflected in public opinion polls, where a majority of the population expressed distrust in the government.

Another notable source of contention was the attempts by the most progressive coalition partner LP to introduce same-sex partnership legislation. Although these efforts ultimately failed (as various bills did not receive a majority in parliament), they contributed to ideological sorting and increased polarization on the issue. Interestingly, right wing parties, on average, took a more progressive stance on this matter compared to the centre left and, in particular, the populist wing of the party system. This relates to the evolution of political cleavages in Lithuania. The main socio-political divide emerged from differing evaluations of the Soviet era. Since the restoration of independence, voters with negative views of the Soviet period have supported right-wing parties, while those with neutral or positive assessments have tended to align with centre-left or populist parties. As this division overlapped with urban–rural divide, right-wing parties came to rely more heavily on younger, urban, and more liberal sociological bases.

The 2020-2024 period was also marked by tensions between the non-partisan president Gitanas Nausėda (elected in 2019) and the right-wing government of Šimonytė. The Lithuanian president holds substantial powers, most notably the right to veto legislation (and propose amendments), appoint key state officials (such as Supreme Court judges) with the assent of the Seimas (Lithuanian parliament), and plays a central role in foreign policy, which is conducted jointly with the government.

Although the president and the government were aligned on key strategic issues (such as support for Ukraine, increased defence spending, and a general pro-Western orientation), personal ambitions and intra-executive competition for power led to a strained relationship. A key point of conflict arose over who should represent Lithuania in the European Council. While the informal tradition (since the presidency of Dalia Grybauskaitė) has been for the head of state to assume this role, the right-wing government unsuccessfully argued that the prime minister should take it on. Furthermore, Nausėda’s more conservative stance on family and same-sex partnership issues, coupled with his preference for larger state spending, also led to ideological disagreements with the governing majority.

To sum up, several underlying causes of the stand-off between the prime minister and the president—which subsequently influenced both the parliamentary and presidential elections—can be identified. The first one stems from Lithuania’s semi-presidential system: non-partisan presidents (the Constitution requires the president to resign from all political organizations, and voters typically elect genuinely non-partisan candidates) face incentives to compete for power with party-led government, also functioning as part of the system of checks and balances. The second source of intra-executive friction was personal rivalry and political competition between President Nausėda and Prime Minister Šimonytė, which has persisted since the second-round of 2019 presidential election (won by Nausėda). Third, ideological differences between the two leaders also played a role in tensions.

Campaign

Due to proximity of the parliamentary and presidential elections, their electoral campaigns partially overlapped. Moreover, the results of the presidential elections were closely linked to the parliamentary elections, as some presidential candidates (most notably Remigijus Žemaitaitis, see below) transferred their newly acquired political capital to electoral success of their parties.

One central axis of competition emerged between the president and the Lithuanian Social Democratic Party (LSDP, S&D), the major opposition party at the time, on one side, and the ruling TS-LKD on the other. Although President Nausėda did not explicitly endorse the Social Democrats in the parliamentary election, he signalled his desire for a change in government and his expectation of a centre-left coalition. Prime Minister Šimonytė ran as a candidate of the TS-LKD in the presidential election and also led the party’s electoral list in the parliamentary elections. The LSDP opted not to field a candidate in the presidential election, instead supporting Nausėda’s candidacy, which allowed Nausėda to easily advance to the second round and secure a landslide victory. From a sociological perspective, the decision appeared reasonable, as studies from the 2019 presidential election (Jastramskis, 2020) showed a significant overlap between the electoral bases of Nausėda and the LSDP.

However, the ideological differences between the two camps (centre-right and centre-left) in both the presidential and parliamentary elections were somewhat blurred. President Nausėda and the leader of the Social Democrats, Vilija Blinkevičiūtė, criticized the government and the TS-LKD primarily for their poor communication and general inability to address the concerns of the population. The centre left also called for greater social justice, the expansion of the welfare state and more attention to regional policy. In general, however, the electoral manifestos of the LSDP and the TS-LKD appeared rather similar.

Alongside these two main camps, a third populist camp emerged, criticizing the entire political system and questioning to a varying extent the strategic pillars of Lithuanian foreign policy. This camp includes political newcomers Ignas Vėgelė, Eduardas Vaitkus and former MP Remigijus Žemaitaitis. The first two rose to prominence during the COVID-19 pandemic, while Žemaitaitis, who supported measures to control the pandemic, attracted most attention during the election campaign due to his character traits, strong rhetoric and a very intense election campaign.

In the presidential election, lawyer Ignas Vėgėlė (non-partisan) appeared as the third most popular candidate in the polls. He gained prominence during the pandemic by challenging vaccination efforts and other pandemic-related measures. He has also taken a conservative stance on same-sex partnerships and family policy. While expressing support for NATO, Ukraine’s independence and territorial integrity, he criticised the foreign policy of the former ruling majority as conflict-mongering. After the presidential elections, Vėgėlė joined the Farmers and Greens Union (LVŽS, ECR group), a socially conservative and economically centre-left party.

Among this camp, another non-partisan Eduardas Vaitkus expressed most radical positions. Similar to Călin Georgescu in Romania, Vaitkus campaigned on openly pro-Russian foreign policy stances, calling NATO an aggressive bloc and advocating for peace in the Russia-Ukraine war (without acknowledging Russia’s initial aggression). Anecdotal evidence suggested that he capitalized on social media, particularly TikTok, to gain political attention. However, Vaitkus received only 7.3 percent of the vote (also see result section) and was unable to translate his partial success into the parliamentary elections, where he joined a list of a relatively marginal Lithuanian People’s party.

The key figure in this third populist camp was Remigijus Žemaitaitis. In April 2024, the Constitutional Court ruled that Žemaitaitis had violated the constitution with his anti-Semitic social media posts. Following this ruling, Žemaitaitis resigned from the parliament to avoid impeachment. Before the verdict, he had been suspended from his membership in the minor Freedom and Justice party, eventually forming his own political party “Dawn of Nemunas” (PPNA).

The Constitutional Court’s decision likely amplified the appeal of aggressive populist rhetoric by Žemaitaitis, which had long been critical of the Lithuanian political elite. Previously he held relatively low influence in Lithuanian politics, having been elected multiple times in his rural SMD in western Lithuania. However, his newly strengthened anti-establishment stance helped him secure a fourth-place finish in the presidential race (also see result section). Moreover, he was able to capitalize on this political momentum, tapping into widespread voter dissatisfaction with political establishment, boosting his party’s support in the parliamentary elections.

In response, the major ruling party TS-LKD made Žemaitaitis a focal point of their campaign, emphasizing the need for a cordon sanitaire to isolate him from the mainstream politics and future government (and pointing to the ruling of the Constitutional Court). Meanwhile, the opposition parties, particularly Social Democrats, rejected the option of a grand coalition with TS-LKD, but also made it clear during the campaign that they were unwilling to cooperate with Žemaitaitis.

Results

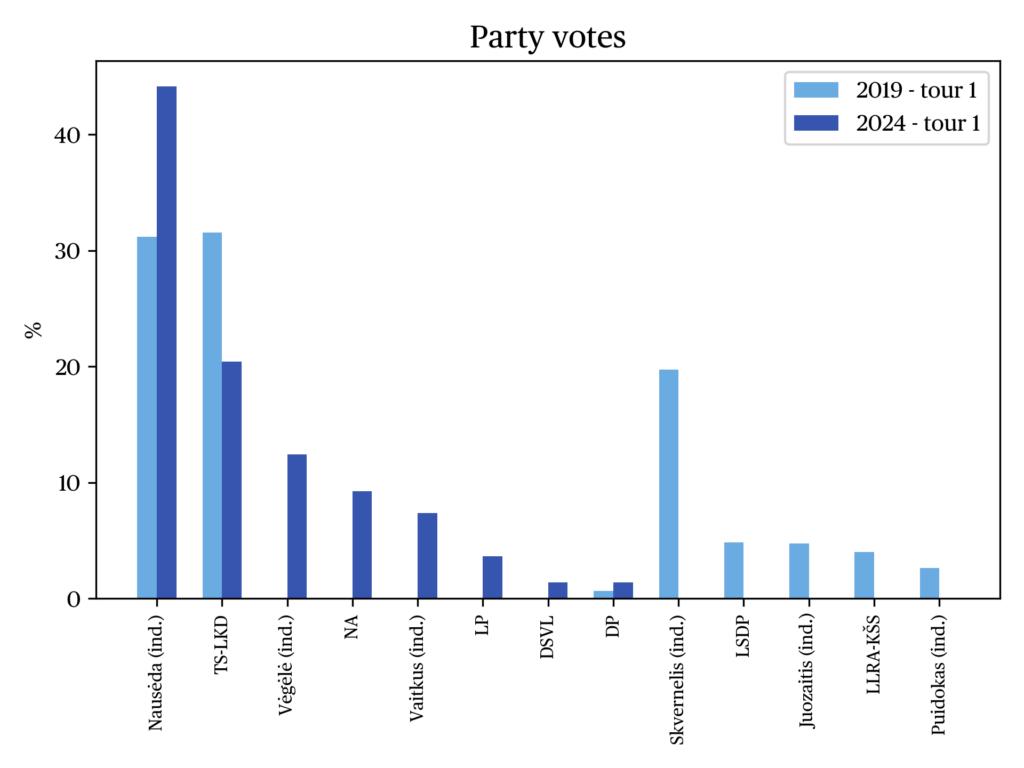

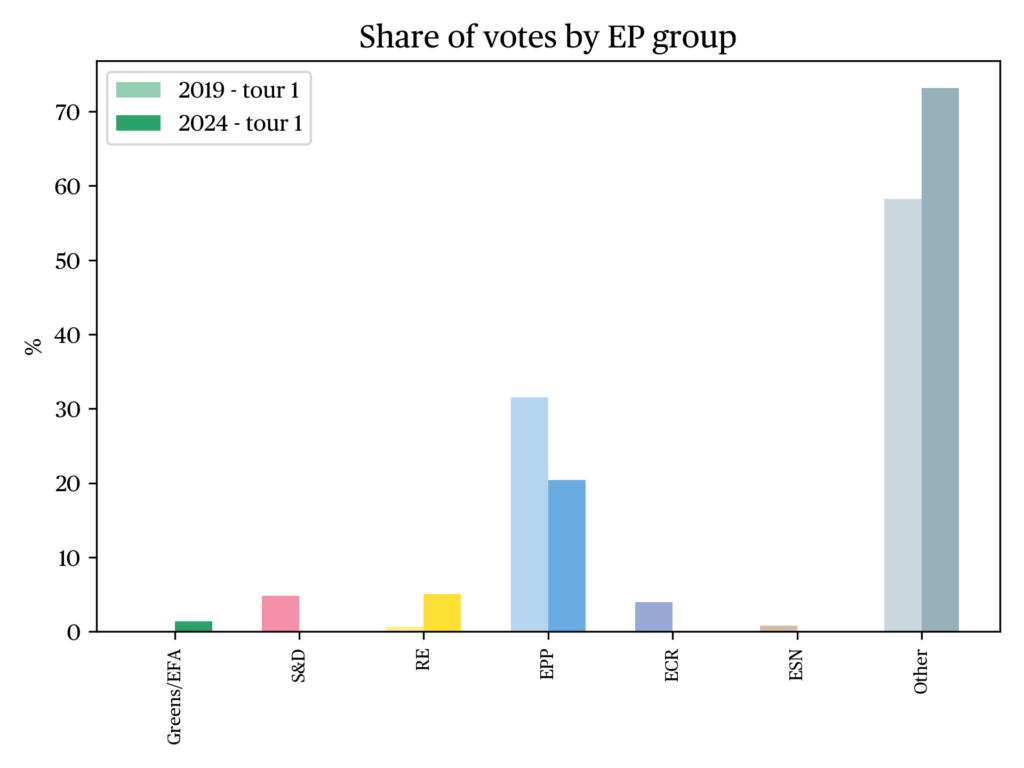

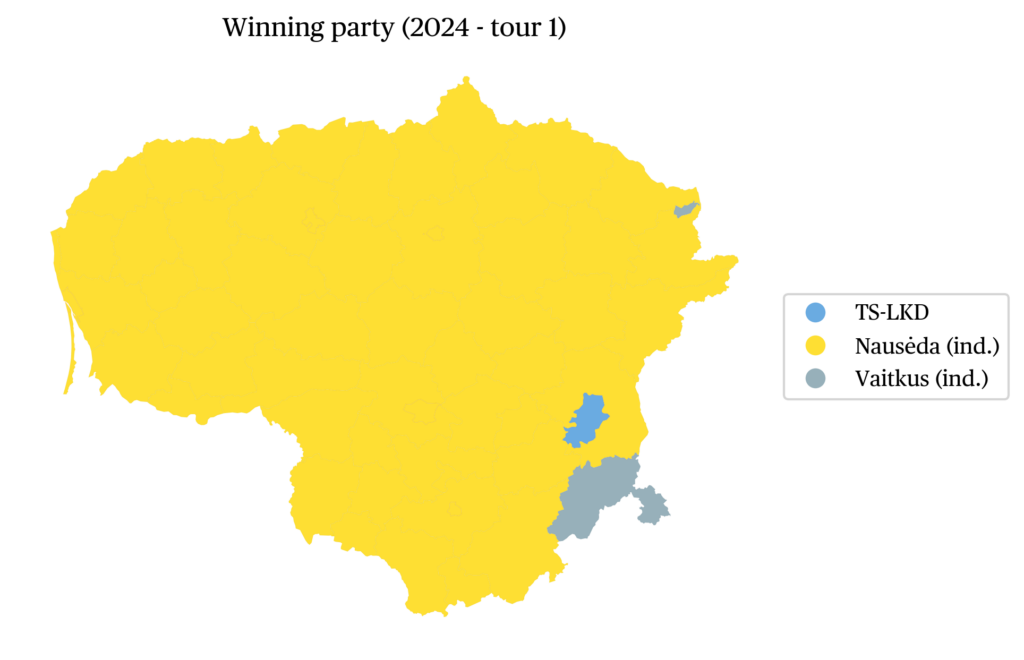

In the first round of the presidential election held on May 12, the incumbent President Gitanas Nausėda emerged as the clear frontrunner. Consequently, the primary question centred on which candidate would secure second place and whether a second round would be needed. The second place was contested by incumbent Prime Minister Ingrida Šimonytė (who came second in the last presidential election in 2019) and political newcomer Ignas Vėgėlė. Although some polling data suggested that Vėgėlė had a viable chance of advancing to the second round (Brunalas, 2024), a significant portion of his potential electorate shifted their support to Remigijus Žemaitaitis. His rising popularity ultimately relegated Vėgėlė to third place with 12% of the vote. Nausėda and Šimonytė advanced to the second round with 44% and 20% of the vote, respectively (see Figure a).

| Candidate | % of votes in the first round 12 May | % of votes in the second round 26 May |

| Gitanas Nausėda | 43.95 | 74.15 |

| Ingrida Šimonytė | 20.05 | 24.34 |

| Ignas Vėgėlė | 12.35 | |

| Remigijus Žemaitaitis | 9.21 | |

| Eduardas Vaitkus | 7.31 | |

| Dainius Žalimas | 3.57 | |

| Andrius Mazuronis | 1.38 | |

| Giedrimas Jeglinskas | 1.37 | |

| Invalid votes | 0.81 | 1.51 |

| Turnout | 59.95 | 49.74 |

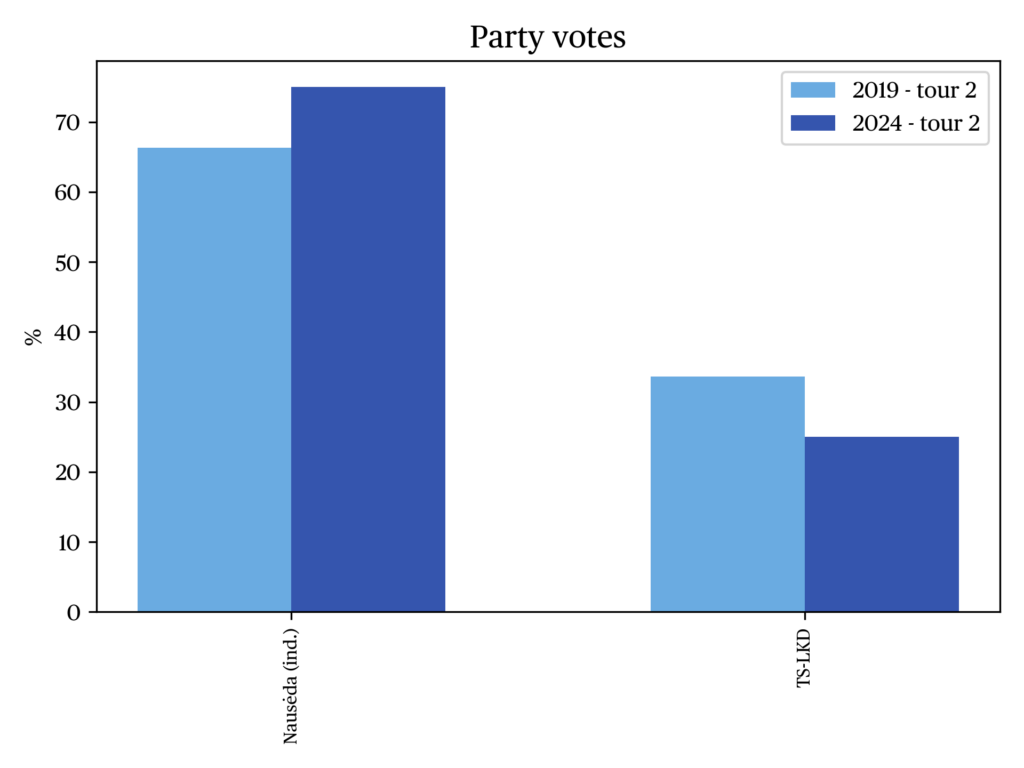

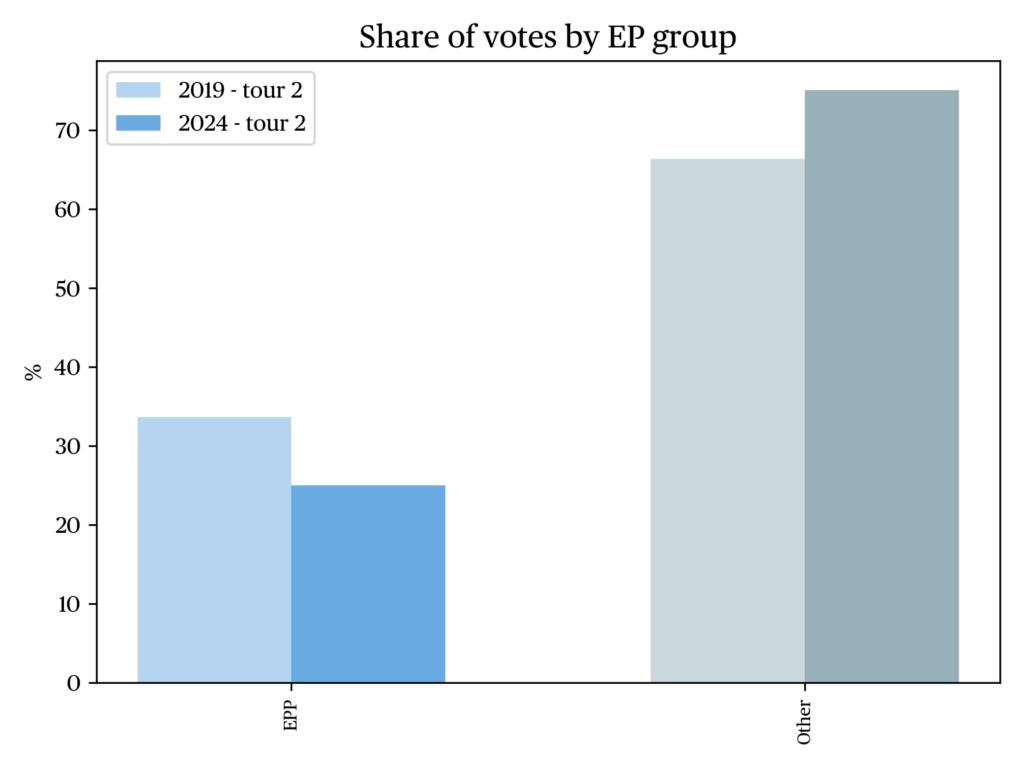

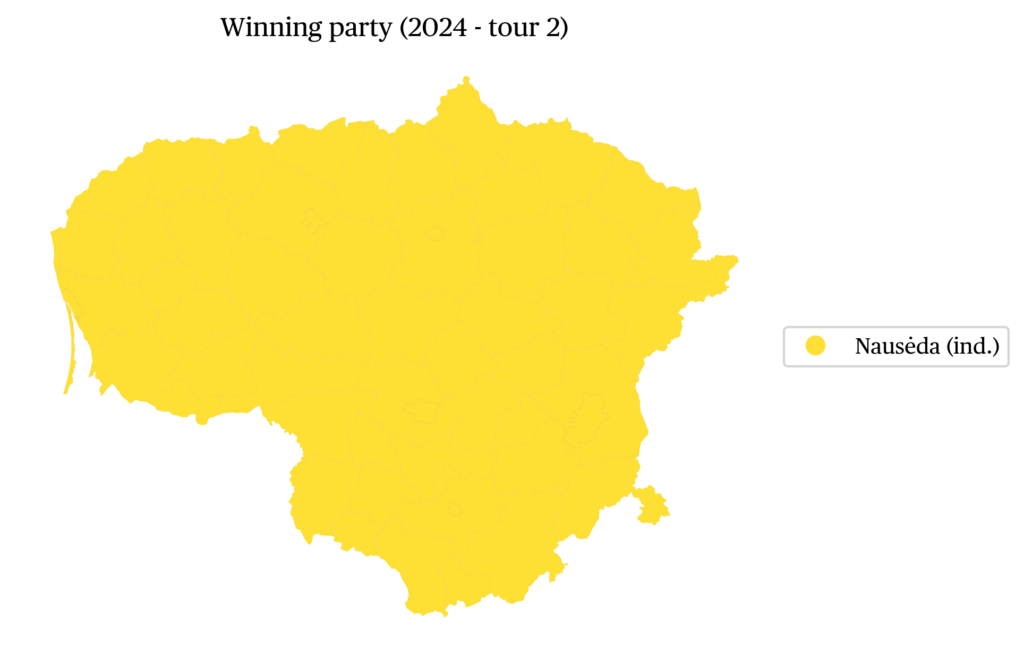

In the second round, conducted on May 26, Nausėda won a landslide victory over Šimonytė, getting the highest-ever support in the history of presidential run-offs in Lithuania (74% of the vote). In contrast, Šimonytė’s support increased by only 4 percentage points compared to her first-round performance. This limited gain can be attributed to the polarizing nature of the Homeland Union, the party Šimonytė represented. The Homeland Union usually gets considerable support from progressive urban voters, particularly in the capital, but faces significant opposition from large segments of the electorate in rural and non-metropolitan areas. As noted previously, this polarization dates back to the post-Soviet transformation in the 1990s; but it was re-enforced again during the covid-19 crisis.

An online panel survey commissioned by Vilnius University and funded by the project “Support for democratic institutions and the polarization of society: an analysis of interactions” (grant no. S-VIS-23-19) revealed that Šimonytė’s voter base in 2024 elections predominantly consisted of urban residents with higher education, whereas Nausėda’s support was drawn from a broader spectrum of societal groups. Another candidate representing the then-ruling majority, Dainius Žalimas of the Freedom Party—who had previously served as Chairman of the Constitutional Court—competed with Šimonytė for a similar electoral base. Žalimas’s support, concentrated among younger urban voters, amounted to only 3.6% of the total vote and thus provided limited assistance to Šimonytė in the second round. Survey data further indicate that a significant proportion of Žalimas’s voters—exceeding one-third—ultimately endorsed Nausėda in the second round rather than Šimonytė.

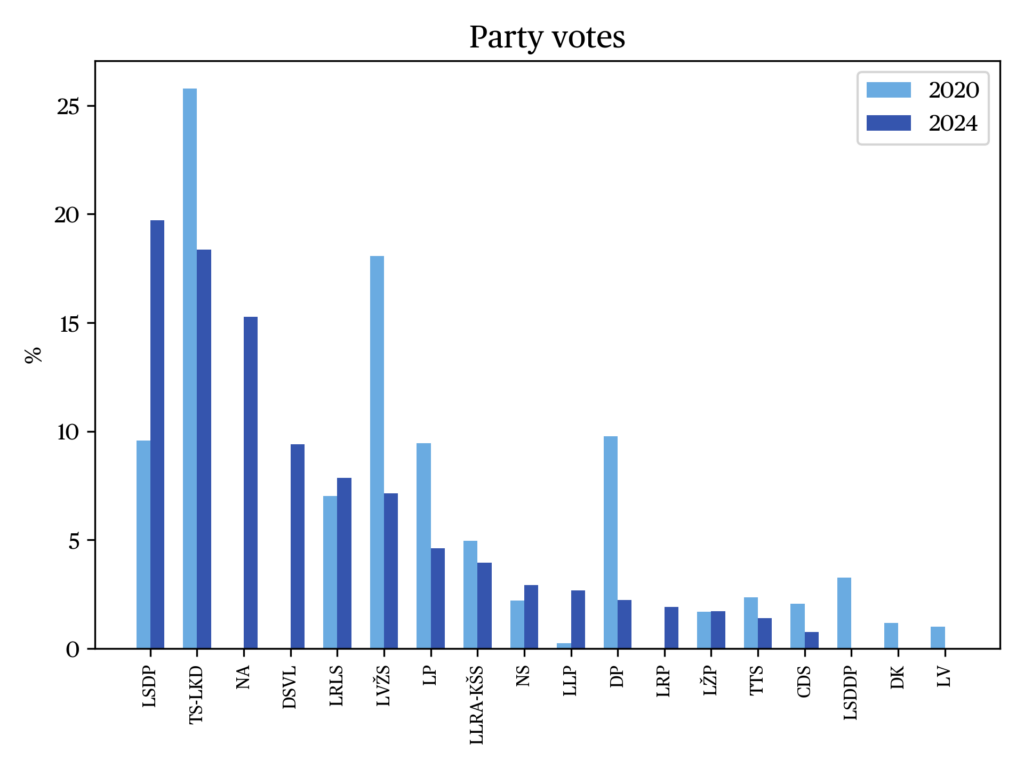

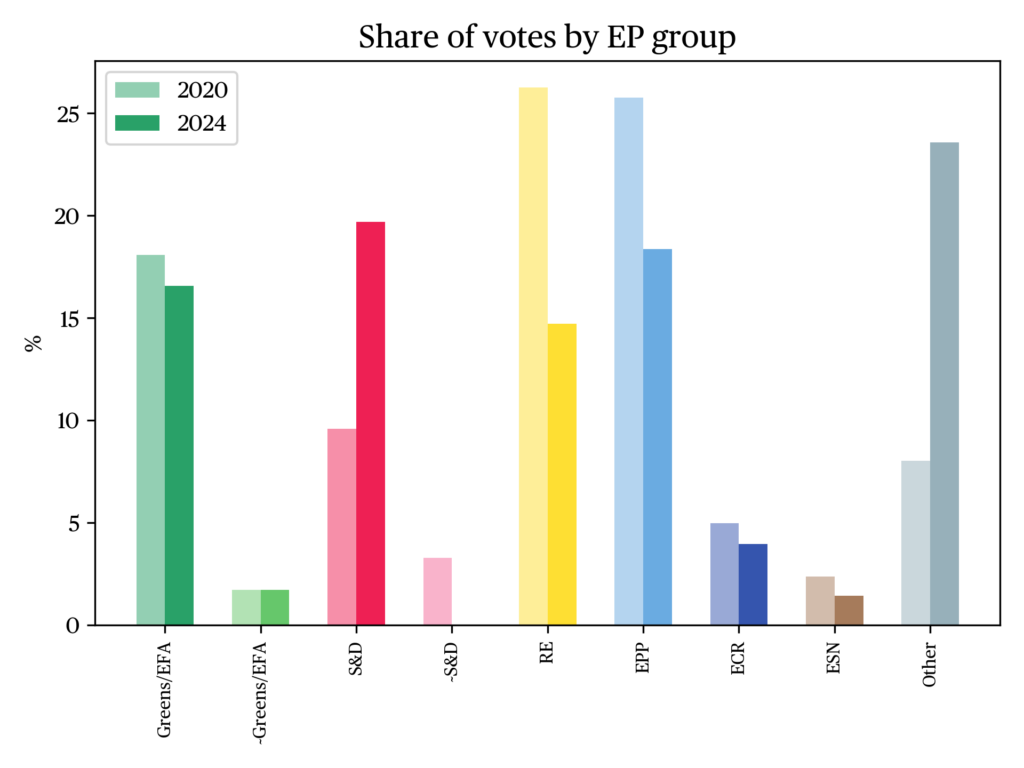

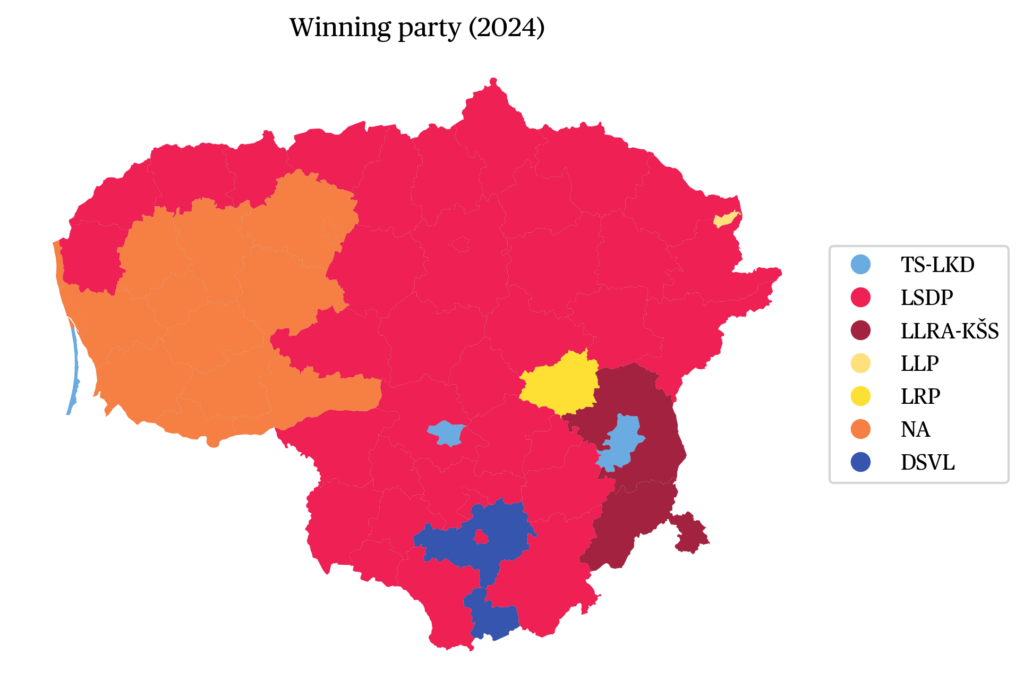

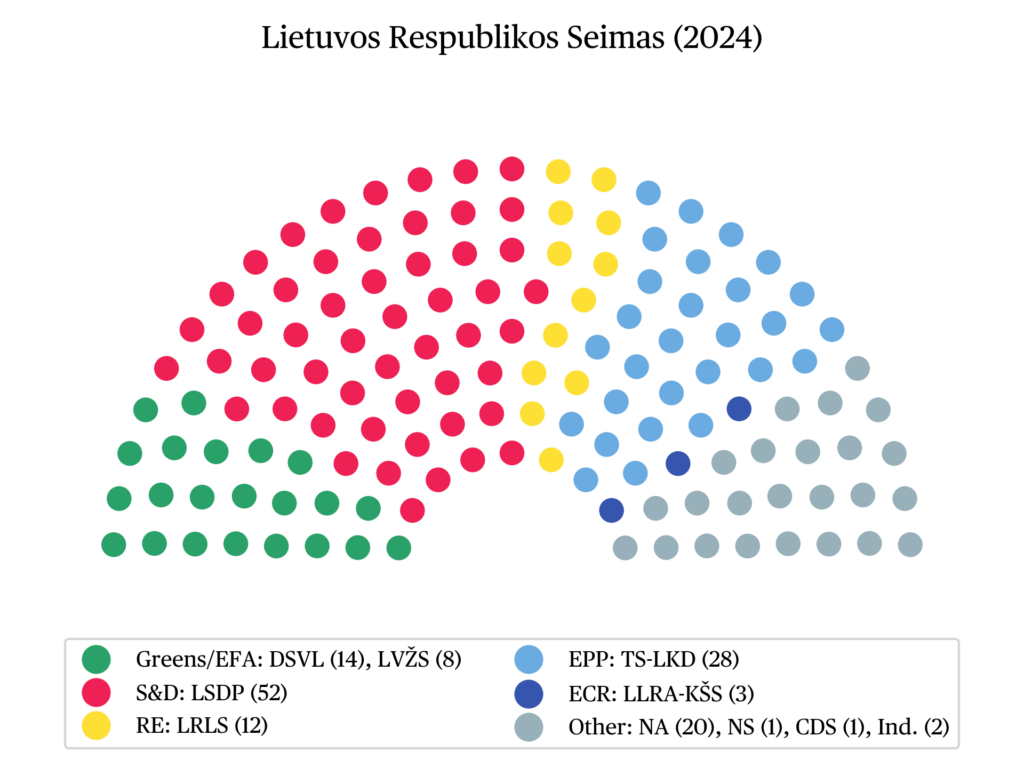

The post-election survey data revealed distinct characteristics among the electorates of the three populist candidates. Vaitkus’s voters stand out for their indifferent attitudes toward defence issues. Vėgėlė’s supporters, like Vaitkus’s, are most notable for their conservative stance on same-sex partnerships. Meanwhile, Žemaitaitis appeals most strongly to those who support a “strong hand” approach. The poll also indicates that Vaitkus received significantly more votes from Russian-speaking and Polish voters than the other candidates. In the parliamentary elections held in October, the Lithuanian Social Democratic Party achieved a decisive victory (Figure b). While the party outpaced the TS-LKD by only one percentage point in the multi-member constituency, securing 19% of the vote and 18 seats, it performed exceptionally well in the second round of single-member constituencies, winning additional 34 seats. This brought its total to a solid 54 seats out of 141. Similar to Nausėda in the second round of the presidential election, LSDP benefited from being a relatively non-polarizing party, appealing to a diverse range of voter groups.

| Party | % of votes in PR tier | Seats won in PR tier | Seats won in SMD |

| Lithuanian Social Democratic Party (LSDP) | 19.32 | 18 | 34 |

| Homeland Union – Lithuanian Christian Democrats (TS-LKD) | 18 | 17 | 11 |

| Political Party “Nemunas Down” (PPNA) | 14.92 | 14 | 6 |

| Democratic Union “For Lithuania” (DSVL) | 9.22 | 8 | 6 |

| Liberal Movement (LS) | 7.70 | 7 | 5 |

| Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union (LVŽS) | 7.02 | 6 | 2 |

| Freedom Party (LP) | 4.53 | 0 | 0 |

| Electoral Action of Poles in Lithuania– Christian Families Alliance (LLRA) | 3.99 | 0 | 3 |

| National Alliance (NS) | 2.87 | 0 | 1 |

| Lithuanian People’s Party (LLP) | 2.64 | 0 | 0 |

| Coalition for Peace (Labor Party, Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party, Samogitian Party) | 2.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Lithuanian Regions’ Party (LRP) | 1.89 | 0 | 0 |

| Lithuanian Green Party (LŽP) | 1.69 | 0 | 0 |

| People and Justice Union (centrists, nationalists) | 1.39 | 0 | 0 |

| Party “Freedom and Justice” (PLT) | 0.75 | 0 | 1 |

| Non-partisans | – | – | 2 |

In contrast, TS-LKD faced challenges similar to those encountered in the presidential election. Although the party performed reasonably well in the first round—securing 18% of the vote and 17 seats—it suffered significant losses in the second round, losing micro-races in single-seat constituencies to nearly all political parties except the even more polarizing Freedom Party (LP). The progressive LP, which emerged as a newcomer in 2020, experienced a disappointing performance in these elections. The party failed to surpass the 5% threshold in the multi-member constituency and did not secure any single-member district seats.

The third partner in the ruling coalition, the Liberal Movement, fared significantly better. Garnering 7.7% of the vote, the party improved upon its 2020 performance in the PR tier and secured 12 seats in total. With a moderate centre-right position, the Liberal Movement managed to attract a portion of TS-LKD’s electorate, as evidenced by the results of the aforementioned panel survey.

One of the most surprising outcomes of the 2024 parliamentary elections was the performance of the newly established party Dawn of Nemunas (PPNA). This party received nearly 15% of the vote, securing 20 seats and claiming third place in the Seimas. Although formally a new political entity, PPNA inherited a portion of its members and voters from the Freedom and Justice Party (which, in turn, inherited part of the members and electorate of the former “Order and Justice” party). Much like its predecessors, PPNA received its strongest support in Samogitia, where its leader, Remigijus Žemaitaitis, conducted the most intensive campaign. The party attracted so-called “protest votes” from those most dissatisfied with Šimonytė’s government and the broader functioning of democracy in Lithuania. Survey data suggest that PPNA managed to draw a significant portion of its support from the Lithuanian Farmers and Greens Union (LVŽS), which performed far worse than expected. While being the second-largest party in 2020 with 17% of the vote, LVŽS garnered only 7% in 2024, even after including Ignas Vėgėlė and his team on their candidate list. LVŽS narrowly avoided failing to enter parliament altogether. Since the party’s candidate list included non-LVŽS members, it was considered a coalition, subject to the higher 7% electoral threshold.

Another key factor contributing to LVŽS’s poor performance was the party’s split in 2021. At that time, former Prime Minister Saulius Skvernelis, along with 15 other MPs, left the political group of the LVŽS to form the Democratic Union “For Lithuania” (DSVL) (see Jastramskis & Ramonaitė, 2022). As a centrist party with a team of well-known politicians—including former European Commissioner Virginijus Sinkevičius—DSVL secured 9% of the vote and won 14 seats in the parliament.

Following the elections, the initiative to form a government was entrusted to the LSDP. On election night, it became clear that the core of the ruling coalition would consist of the LSDP and the DSVL; however, the mandates secured by these two parties (64 out of 141) were insufficient to form a majority. Unwilling to form a coalition with its former counterparts in the LVŽS, the DSVL advocated for the inclusion of the Liberal Movement in the coalition. Nevertheless, this proposal was met with limited support from both the LSDP and the Liberal Movement itself.

Ultimately, in a move that surprised many, Gintautas Paluckas, the Prime Minister-designate nominated by the LSDP (LSDP President Vilija Blinkevičiūtė refused to take up the post of Prime Minister, choosing instead to retain the seat she won in the European Parliament), extended an invitation to PPNA to join the coalition, despite the LSDP’s campaign promise to avoid collaboration with the party. President Nausėda agreed to confirm the ministers of such a government only under the condition that no members of PPNA, including its leader Remigijus Žemaitaitis—who was facing legal proceedings related to anti-Semitic statements—would serve as ministers. While in Lithuania’s semi-presidential system, president approves the composition of the government, this process remains a somewhat grey area within the constitutional framework. On one hand, constitutional doctrine in Lithuania does not grant the president the authority to influence the party makeup of the parliamentary governing coalition. On the other hand, the president may navigate this grey area using his or her informal powers—such as public authority—and may attempt to (pre-emptively) reject certain ministerial candidates, as President Nausėda did with the PPNA. Accordingly, PPNA was required to nominate nonpartisan candidates for ministerial positions. The party accepted these terms, and on December 12, the new cabinet of ministers was approved by the Seimas (BNS, 2024).

The data

Presidential election: first round

Presidential election: second round

Parliamentary election (constituency votes)

References

BNS (2024). Lithuanian lawmakers approve new government programme, cabinet sword in. LRT.lt.

Brunalas, B. (2024). Intriga išlieka: skelbiami naujausi kandidatų į prezidentus reitingai. LRT.lt.

Jastramskis, M. (2020). Kas už ką balsavo 2019 metų Lietuvos prezidento rinkimuose? Politologija, 97(1), 8–41.

Jastramskis, M., & Ramonaitė, A. (2022). Lithuania: Political Developments and Data in 2021. European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook, 61, 299–306.

citer l'article

Mažvydas Jastramskis, Ainė Ramonaitė, Presidential and parliamentary elections in Lithuania, May and October 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue