Presidential election in Slovakia, March-April 2024

Ľubomír Zvada

PhD candidate at Palacký University OlomoucIssue

Issue #5Auteurs

Ľubomír Zvada

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

Introduction

After President Zuzana Čaputová announced that she would not seek re-election in 2024, it was clear that Slovaks would have a new President. The election which took place on 23 March and 6 April was won in the second round by Peter Pellegrini, who defeated his opponent, long-serving diplomat and former foreign minister Ivan Korčok. Pellegrini became the first politician in modern Slovak history to hold all the highest constitutional offices, having previously served as speaker of parliament (2014-2016, 2023-2024) and prime minister (2018-2020).

This text has several aims. First, it outlines the broader historical background of the presidential election in Slovakia and the legal framework under which the 2024 election took place. Second, it discusses the context of the 2024 presidential election and the candidate nomination process. Third, it presents the highlights of the candidates’ campaigns in both rounds and outlines the reasons behind Peter Pellegrini’s victory, inquiring from which electoral groups and regions Pellegrini drew his electoral support. Finally, this contribution discusses the impact of Pellegrini’s victory on the current and future direction of Slovak politics.

Historical background and legal framework of the presidential election

The presidential tradition in Slovakia undoubtedly goes back to the 1918-1939 period, when Slovakia was a part of Czechoslovakia. However, unlike in the Czech Republic – which proudly claims the era of interwar Czechoslovak democracy – Slovak political elites are much more hesitant to claim this period (Brunclik et al., 2023, p. 121). Hence, in Slovakia, it is not the presidential tradition represented by T. G. Masaryk or Edvard Beneš that is highlighted; on the contrary – from a historical perspective – the presidency is most associated with the names of Jozef Tiso or Gustáv Husák as representatives of two undemocratic regimes.

Considering this lack of historical experience with the office of the president and its representatives, a completely new history of the office began to be written with the establishment of the Slovak Republic in 1993. The very first president in the era of Slovak independence, Michal Kováč – who was the only president indirectly elected by parliament – is considered by society to represent a certain archetype of how the presidential office should be exercised. President Kováč was the candidate nominated by the most powerful party at the time, the HZDS (The Movement for a Democratic Slovakia, Hnutie za demokratické Slovensko) led by Vladimír Mečiar. However, soon after taking office, Kováč began opposing Mečiar’s authoritarian ambitions and became one of the main anti-Mečiar figures in Slovak politics. The dispute between Prime Minister Mečiar and President Kováč over the character of the future Slovak political system culminated after the end of Kováč’s mandate, when PM Mečiar, acting as an interim President, granted an infamous series of amnesties in cases related to the kidnapping of the President’s son abroad and the failed referendum of 1997. As parliament was unable to elect another president and Slovakia faced an institutional crisis, the possibility of changing the procedure for electing the president became one of the main issues in the 1998 campaign. The HZDS managed to win the election but was unable to form a majority coalition in parliament. As a result, a broad anti-Mečiar alliance led by the SDK (Slovak Democratic Coalition, Slovenská demokratická koalícia) and including parties such as SDĽ (Party of the Democratic Left, Strana demokratickej ľavice), SMK (Party of the Hungarian Coalition, Strana maďarskej koalície), and SOP (Party of Civic Understanding, Strana občianskeho porozumenia) passed a series of constitutional amendments that included changing the method of electing the president from indirect to direct. In 1999, Rudolf Schuster became the first President to be elected by direct vote, with the election seeing an unprecedented turnout in both the first (73.89%) and second (75.45%) rounds. Turnout has been significantly lower in each of the subsequent elections. Schuster was succeeded by Ivan Gašparovič, who was the only present to be reelected for a second term.

The 2014 and 2019 elections marked a significant shift in the perception of the presidency itself, as the office was filled for the first time by a new generation of politicians. Both Andrej Kiska and Zuzana Čaputová ran as independent candidates who managed to defeat the candidates of the strongest party, Smer-SD (Direction-Social Democracy) – Robert Fico and Maroš Šefčovič respectively. The non-partisan candidates’ triumph was primarily framed as a victory over the existing political establishment and corrupt politicians. However, the 2019 election also saw the lowest voter turnout in history, below 50% in both rounds, with the second round seeing the lowest turnout ever with only 41.79% of eligible voters going to the polls (Štatistický úrad Slovenskej republiky, 2019).

As the Slovak Republic is a parliamentary democracy, the role of the President is mostly representative, symbolic and ceremonial (Giba, 2011). Similarly to presidents in other parliamentary democracies, the Slovak president acts as a kind of arbiter trying to control the power of the government and parliament (Brunclík & Kubát, 2019, pp. 52–53).

The President of the Slovak Republic is elected by direct vote for a five-year term. Any citizen of the Slovak Republic over the age of 40 who is nominated by at least 15 members of parliament or collects 15,000 signatures from citizens may run for the presidency. A two-round majority system is used. In the first round, any candidate who receives a majority of the votes of all eligible voters is elected. If no candidate is elected in the first round, a second round is held 14 days later, in which the two candidates with the highest number of votes from the first round face each other. In the second round, the candidate with the highest number of votes is elected (Národná Rada Slovenskej Republiky, 2023).

Unlike in Czechia, voting takes place on a single day (Kubát, 2023). Voting is possible only at a polling station on the territory of the Slovak Republic; a citizen of the Slovak Republic who has reached the age of 18 no later than the day of the election may vote either in the municipality of his/her permanent residence or at any polling station if he/she has applied for an electoral card. The law sets the limit for campaign expenses at a total of €500,000 including VAT for both rounds of the election. This amount includes the costs used by the presidential candidate for advertising in the period beginning 180 days before the date of the announcement of the election (i.e. from 13 July 2023) and the costs paid or to be paid by the presidential candidate. The election campaign for President of the Slovak Republic officially began on Tuesday, 9 January, the day the decision to call the election was published in the Collection of Laws of the Slovak Republic. It ends 48 hours before the day of the first round, i.e., at midnight on 20-21 March, when the election moratorium begins. If a second round is held, the campaign ends at midnight between 3 and 4 April (Ministerstvo vnútra Slovenskej Republiky, 2024).

Broader election context and candidate selection process

The 2024 presidential election in Slovakia must be considered in its broader context. Several events and external factors have shaped the overall electoral climate, with three key moments likely significantly influencing the outcome of the election election.

President Čaputová – the first woman elected to the presidency of Slovakia in 2019 – announced that she would not seek a second term on 20 June 2023, citing personal reasons (The Guardian, 2023). During her time in office, Čaputová has faced relentless smear campaigns from Smer-SD and far-right parties such as K-ĽSNS (Kotlebists People’s Party Our Slovakia, Kotlebovci – Ľudová strana naše Slovensko) and Republika (The Republic), who labelled her an American agent and subjected her to misogynistic slurs. This led to death threats targeting her and her family.

The problematic governance of the centre-right government that emerged from the 2020 parliamentary election also conditioned the electoral context. In the 2020 election, OĽaNO (Ordinary People and Independent Personalities, Obyčajní ľudia a nezávislé osobnosti) had defeated Robert Fico’s Smer-SD and formed a coalition with other parties such as SaS (Freedom and Solidarity, Sloboda a solidarita), Za Ľudí (For the People) and Sme rodina (We are Family). However, the center-right’s governance has been marred by persistent intra-party conflicts. This was mainly due to the populist leadership style of OĽaNO leader Igor Matovič. While these conflicts eventually led to Matovič’s resignation and subsequent appointment as finance minister, tensions within the coalition continued to escalate even after his fellow party member, Eduard Heger, replaced him as Prime Minister. As a result of the ongoing crisis, the SaS ministers, including Korčok, who was serving as foreign minister, withdrew from the coalition (Kern, 2022). Finally, in December 2022, the parliament passed a vote of no confidence against Heger’s government. As a result, for the first time since 1993, President Čaputová decided to appoint a caretaker government headed by Ľudovít Ódor to lead the country until early parliamentary election, the date of which was set for 30 September 2023.

The turmoil during the Matovič and Heger governments was used by Fico and Smer-SD to stage a comeback. After the snap election, Fico formed his fourth government in seventeen years with the support of the SNS (Slovak National Party) and Pellegrini’s newly formed Hlas-SD party – which had emerged from a split with Smer-SD –, securing a parliamentary majority of 79 out of 150 seats (Gyarfášová, 2024). Fico and his party took advantage of the insecurity resulting from a series of crises that the government had to deal with, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and the energy crisis. Fico’s victory in the snap election relied on polarising rhetoric and a campaign marked by hostility towards all the main political actors: the Matovič and Heger governments, the Ódor caretaker government, President Čaputová, liberalism, the EU, etc. Smer-SD’s opposition policy was based on divisive discourses that undermined democratic institutions and the independence of the judiciary, with party speeches built on oppositions between “us” and “them”. In this way, Smer-SD has shifted towards more extreme right-wing discourse than ever before. Some of the party’s statements on foreign policy or reflections on the war in Ukraine do not support the official and common goals and principles formulated by the EU and NATO (Zvada, 2023, pp. 216–217). The war in Ukraine and the struggle over the interpretation of this event – which was very visible during the parliamentary election campaign – became one of the main issues of the presidential campaign.

Multiple parties and potential candidates considered whether to run in the election given this political context. Ultimately, a total of eleven candidates entered the presidential race. Four of them ran as independents (Ivan Korčok, Ján Kubiš, Štefan Harabin, Milan Náhlik), while others represented specific political parties. A political climate hostile to President Čaputová undoubtedly contributed to the lack of any female candidates in the 2024 presidential race, a situation that last occurred in 2004. According to long-term polls, the race for the presidential seat had narrowed down to a contest between Ivan Korčok, an independent supported by a wide range of opposition parties, including Progresívne Slovensko (PS), the Democrats, KDH and Most-Híd, and Peter Pellegrini (Hlas-SD) as the main candidate of the ruling coalition, supported by Smer-SD. In retrospect, it seems quite likely that Pellegrini’s candidacy had already been anticipated months earlier, during the negotiations over the formation of the new Fico government.

Interestingly, neither the opposition nor government parties nominated a single candidate. The junior coalition party SNS nominated its leader Andrej Danko. In addition to Korčok, the opposition parties nominated several candidates such as former PM Igor Matovič (supported by the Slovakia party, formerly known as OĽANO) and Patrik Dubovský (supported by Za ľudí, For the People). Krisztián Forró (Szövetség-Aliancia), the leader of an extra-parliamentary party representing the Hungarian minority, also participated in the first round. In addition, four candidates that can be labelled as anti-system took part in the election, including independent Štefan Harabin, leader of the far-right K-ĽSNS party Marian Kotleba, independent Milan Náhlik, and Robert Švec from SHO (Slovenské hnutie obrody, Slovak renewal movement). Finally, two of the candidates, Andrej Danko (SNS) and Robert Švec (SHO) withdrew before the first round of voting. In the end, Slovak voters could choose between nine candidates in the first round.

Campaigning

The campaign leading up to the first round remained relatively lukewarm, with some of the actions taken by the Fico government attracting public scrutiny. These included controversial ministerial appointments, the approval of the budget, and efforts to revise the penal code (Bahounková, 2024).

Ivan Korčok’s campaign was based on slogans such as “Serve the people, not the politicians” or the more direct “Let’s not let them take over the whole state”. Above all, Korčok systematically pointed out the unfairness of the election campaign, accusing Pellegrini of abusing his position as speaker for electoral purposes. He also highlighted the intransparent financing of Pellegrini’s campaign. In contrast, Pellegrini focused on avoiding a direct confrontation with Korčok before the first round. Only two debates took place within 48 hours, with the other candidates on RTVS (Radio and Television of Slovakia) and on the private channel TV Markíza. Pellegrini chose the slogan “Calm for Slovakia” as his main claim before the first round. Despite the President´s lack of power regarding concrete policymaking, he also presented himself as a “president who would bring dignity and a better life to Slovak people.”

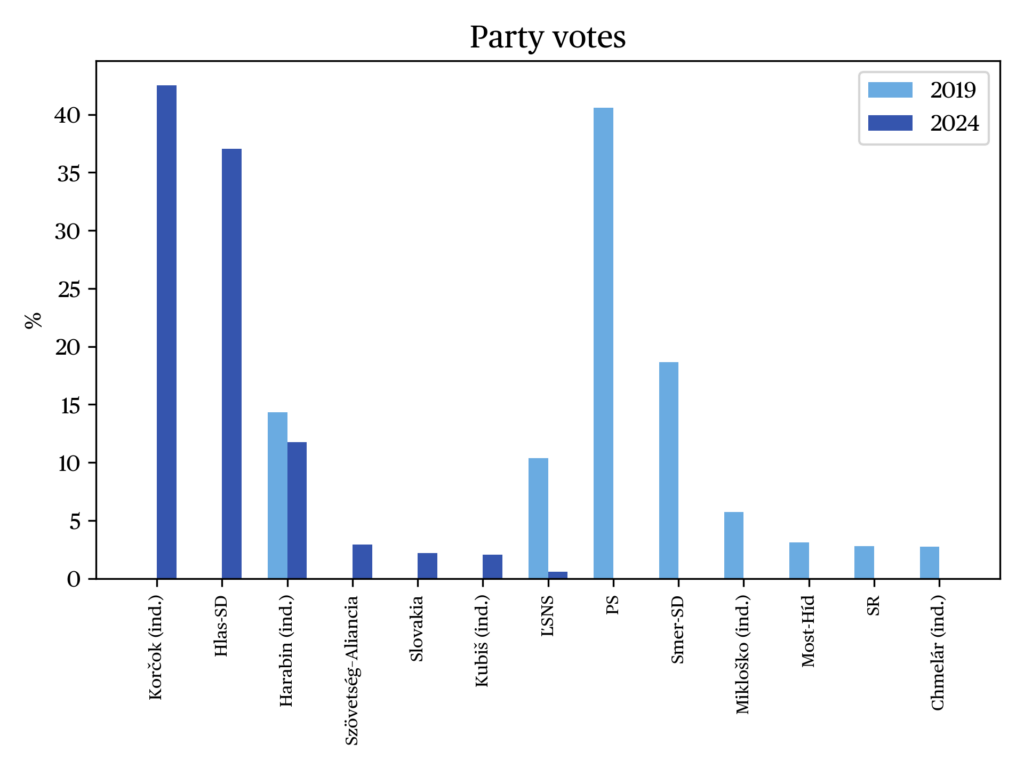

Pellegrini’s lackluster campaign, his refusal to participate in the debates and his overconfidence in winning the first round (as predicted by all relevant polls in Slovakia) led to Korčok’s surprise victory in the first round. Korčok defeated Pellegrini by 42.51% (958 393 votes) to 37.02% (834 718 votes) with a turnout of 51.9%.

Despite both candidates’ commitments to running a fair and respectful campaign ahead of the second round, the race devolved into an unprecedentedly negative and hostile contest.

Prior to the first round, Pellegrini projected an image of calm and composure. However, after being outpolled by Korčok in the first round, he shifted to a more confrontational strategy, recognizing the need to mobilize both his base and those who had backed anti-system candidates – particularly the voters who supported Štefan Harabin. Pellegrini’s campaign was characterized by a frequent use of fearmongering, particularly concerning the ongoing war in Ukraine. Pellegrini constructed a narrative labelling Korčok “the president of conflict and war” while positioning himself as a candidate committed to ensuring a dignified existence for all citizens – branding himself as a “president of peace”. While Pellegrini claimed “Slovakia needs peace now” (Slovensko už potrebuje pokoj) – hinting at the years under the previous government which were marked by disputes, clashes and unrest –, Korčok campaigned with the slogan “Cooperation. Experience. Service to the country” (Spolupráca. Skúsenosť. Služba vlasti.).

During a televised debate on RTVS, Pellegrini insinuated that Korčok would advocate for the deployment of troops to Ukraine, asserting that he himself would never permit such actions. This kind of rhetoric aligned closely with the narratives espoused by Prime Minister Fico, which stand in direct opposition to the official stance of the both European Union and NATO in the conflict. On the other hand, Korčok tried to capitalize on his success in the first round, but he also brought in new themes, including, for example, his vision of patriotism – which he aimed not only to restore to its original essence but also to redefine with a new meaning (Týždeň, 2024).

While Pellegrini also accused Korčok of engaging in negative campaigning, a critical distinction must be made: Pellegrini orchestrated a campaign rooted in hostility – supported by his party and coalition allies – whereas the negative discourse directed at Pellegrini was primarily spearheaded by Igor Matovič rather than Korčok himself. In contrast to Pellegrini, who denied any involvement in the manipulation of imagery and the negative campaigning, Korčok vocally condemned Matovič’s homophobic interference and other attacks that targeted Pellegrini’s personal integrity.

Results

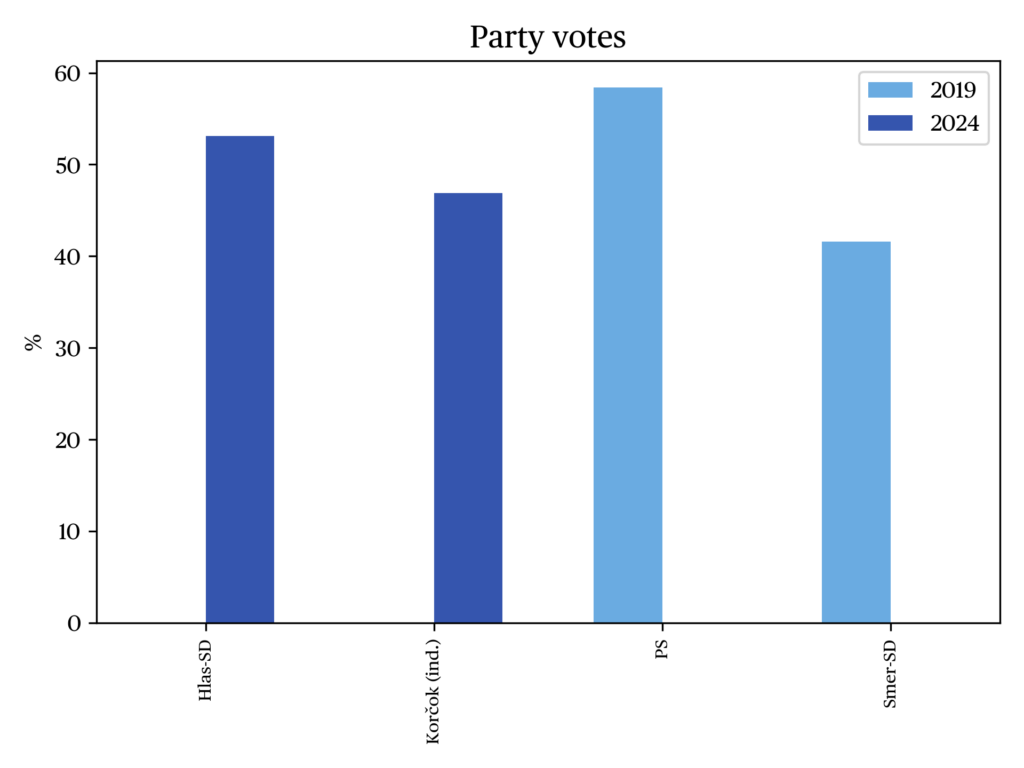

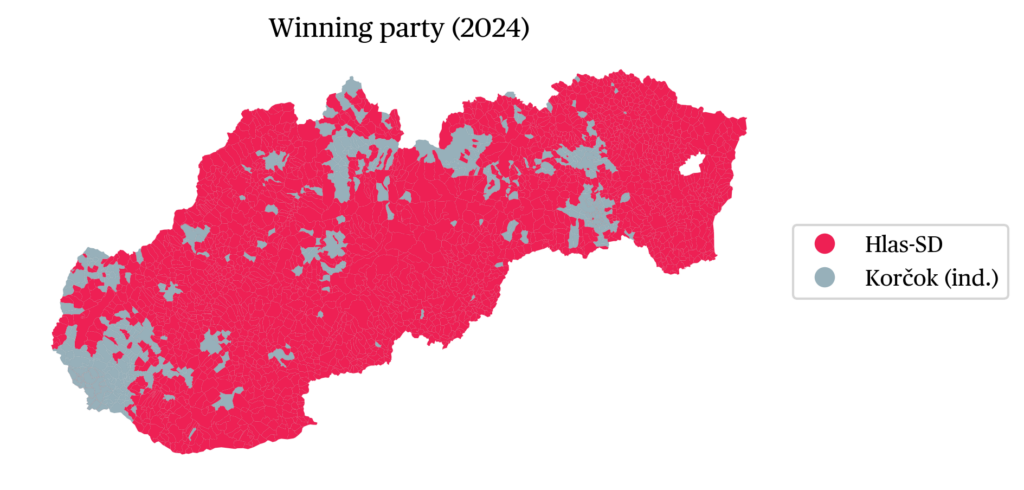

On April 6, the Slovak electorate went to the polls, resulting in the election of Peter Pellegrini as president of the Slovak Republic with a margin of 53.12% to 46.87% (Štatistický úrad Slovenskej republiky, 2024). Several key factors contributed to Pellegrini’s victory.

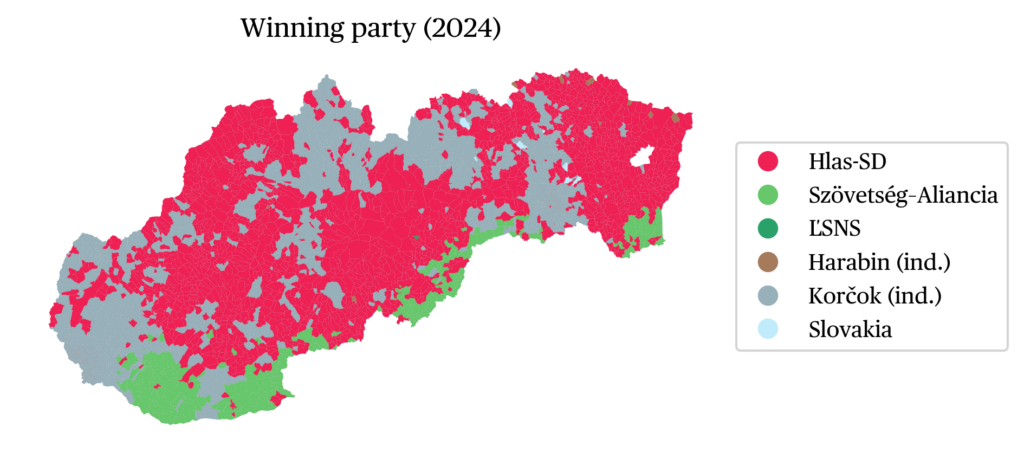

First, his support base primarily consisted of voters from Smer-SD, Hlas-SD, and various illiberal actors. While both candidates mobilized their respective electorates in the second round, Pellegrini demonstrated a significantly greater ability to attract voters, securing an additional 574,537 votes compared to Korčok’s 285,316. Although Korčok garnered a slightly higher share of the vote in urban areas, Pellegrini’s support was significantly stronger in rural regions. Voter turnout was another critical factor. Largely driven by Pellegrini’s intense and polarizing campaign, the election recorded the second-highest voter turnout in the country’s presidential history. Korčok’s refusal to engage in negative campaigning and his decision not to seek support from anti-system candidates prior to the second round may have hindered his electoral prospects. On the other hand, Pellegrini successfully mobilized a significant part of the anti-system vote, including former Harabin voters, in the first round.

Korčok was also less effective than Pellegrini at mobilizing Hungarian voters. In previous elections (2014 and 2019), Hungarian voters had supported both election winners – Andrej Kiska and Zuzana Čaputová – whose campaigns benefited significantly from the Hungarian vote (Zvada, 2020). Before the second round of the 2024 election, Slovak Hungarians predominantly favored Pellegrini or did not vote. In the end, beyond the demobilization of Hungarian voters, some analysts pointed out that the abstention of OĽaNO (now rebranded as Slovensko) vote also contributed to Korčok’s defeat. Approximately three-quarters of those who voted for OĽaNO in the 2020 parliamentary election abstained from participating in the second round of the presidential election (Vančo et al., 2024).

Implications

President Peter Pellegrini took office on 15 June 2024. Although he has been in office for only a few months at the time of writing, several key moments have already emerged that may signal the future direction his presidency is likely to take.

First, Pellegrini approved the government’s nomination of Pavel Gašpar as the new director of the Slovak Information Service. Pavel Gašpar is the son of Tibor Gašpar – a former police chief, current MP, and deputy speaker of parliament for Smer-SD (Hüttner, 2024) – who was forced to resign following the 2018 murder of an investigative journalist. Tibor Gašpar was later investigated and imprisoned in a corruption case during the Matovič and Heger governments. Pavel Gašpar’s qualifications to lead the institution have been questioned in political and security circles and is an open manifestation of the never-ending nepotism in Slovak politics, raising questions about Pellegrini’s ability to select competent individuals to fill key positions in the security apparatus.

Second, Pellegrini has proved relatively passive on the issue of filling the post of Speaker of the Slovak Parliament – the second highest constitutional post. According to the Prime Minister’s current statements, this post may remain vacant until the end of the current coalition’s term. This situation is causing tensions between Pellegrini’s former party Smer-SD and the Slovak National Party (SNS), as SNS leader Andrej Danko had laid claim to the post after having endorsed Pellegrini ahead of the second round of the presidential election.

Third, Pellegrini decided not to use his veto right after the approval of the so-called consolidation package prepared by the fourth Fico government. This package increases the basic VAT rate from 20% to 23%, which is expected to have a negative impact on middle-class, low-income and vulnerable groups in Slovak society such as families with children and pensioners. On the other hand, the consolidation ensures the highest budget for the Office of the President in history (Kalmanová, 2024).

Fourth, it appears that Pellegrini’s role is linked to the current government coalition from which he emerged, rather than being a non-partisan president. Although Pellegrini originally pledged to be a president who would unify society, actual developments point in the opposite direction. Apart from a joint statement by Pellegrini and Čaputová meant to reassure Slovak society following the assassination attempt on Prime Minister Fico in May 2024, Pellegrini has so far presented himself as a president exercising his mandate from afar, refraining from any significant involvement in the political arena.

Pellegrini’s victory in the presidential election marked the culmination of the success of illiberal forces in Slovak parliamentary elections, resulting in their full control over both the legislative and executive branches of the government. His presidency will be heavily shaped by the outcome of the last parliamentary vote, with the strength and stability of his alliance with the dominant political force – Smer-SD and its leader Robert Fico – playing a crucial role in shaping the course of his tenure. This relationship will also be a key factor in determining the prospects of a potential re-election.

The data

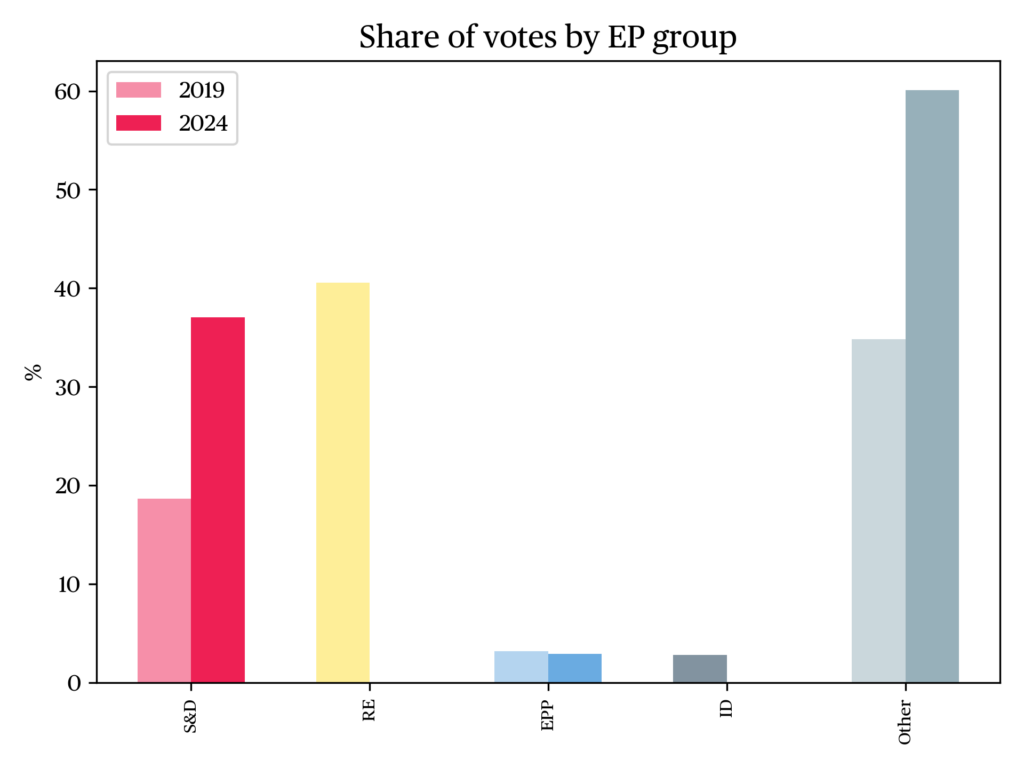

First round

Second round

References

Bahounková, P. (2024, 21 March). Slovensko má za sebou „nejnudnější” kampaň. Zastínila ji Ficova vláda. Česka Televize.

Brunclík, M., Kubát, M., Vincze, A., Kindlová, M., Antoš, M., Horák, F., & Hájeket L. (2023). Power Beyond Constitutions: Presidential Constitutional Conventions in Central Europe. Springer International Publishing.

Brunclík, M., & Kubát, M (2019). Semi-Presidentialism, Parliamentarism and Presidents: Presidential Politics in Central Europe. Routledge.

Giba, M. (2011). Vplyv priamej voľby na ústavné postavenie prezidenta republiky na Slovensku. AUC IURIDICA, 57(4), 101–113.

Gyarfášová, O. (2024). Parliamentary Election in Slovakia, 30 September 2023. Electoral Bulletins of the European Union (BLUE), 4. Groupe d’études géopolitiques.

Hüttner, R. (2024, 26 August). SIS má po roku nového riaditeľa. Pellegrini Vymenoval Gašpara Za Šéfa Tajných. Pravda.

Kalmanová, M. (2024, 18 October). Prezident Pellegrini podpísal konsolidačný balík, minister Šaško zohnal vyše 100 miliónov na platy zdravotníkov. RTVS.

Kern, M. (2022, 27 August). Posledný pokus o záchranu koalície zlyhal, ministri Sas podajú demisie. Denník N.

Kubát, M. (2024). Presidential Election in the Czech Republic, 13-14 January 2023. Electoral Bulletins of the European Union (BLUE), 4. Groupe d’études géopolitiques.

Národná Rada Slovenskej Republiky (2023). Ústava SR.

Ministerstvo vnútra Slovenskej republiky (2024). Prezidentské VOĽBY 2024 – Prehľad dôležitých lehôt.

Štatistický úrad Slovenskej republiky (2019). Súhrnné Výsledky Hlasovania. Voľby Prezidenta Slovenskej Republiky 2019.

The Guardian (2023, 20 June). Slovakian President Čaputová Says She Will Not Run for Re-Election. The Guardian.

Týždeň (2024, 30 March). Ivan Korčok: Chcem vrátiť vlastenectvu pôvodný zmysel a dať mu nový obsah. Týždeň.sk.

Vančo, M., Škop, M., & Mahdalová, K. (2024, 16 April). Voliči Aliancie a bývalého OĽaNO ostali v 2. kole doma (Analýza prezidentských volieb). SME.

Zvada, Ľ. (2023). The State of Social Democracy in Slovakia: The Twilight (or Rebirth) of Social Democracy? In A. Skrzypek & A. Bíró-Nagy (Eds.), The Social Democratic Parties in the Visegrád Countries. Springer International Publishing.

Zvada, Ľ., Petlach, M., & Ondruška, M. (2020). Where Were the Voters? A Spatial Analysis of the 2019 Slovak Presidential Election. Slovak Journal of Political Sciences, 20(2), 176–205.

citer l'article

Ľubomír Zvada, Presidential election in Slovakia, March-April 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue