Regional election in Andalusia, 19 June 2022

Issue

Issue #3Auteurs

Leticia M. Ruiz Rodríguez , David H. Corrochano

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

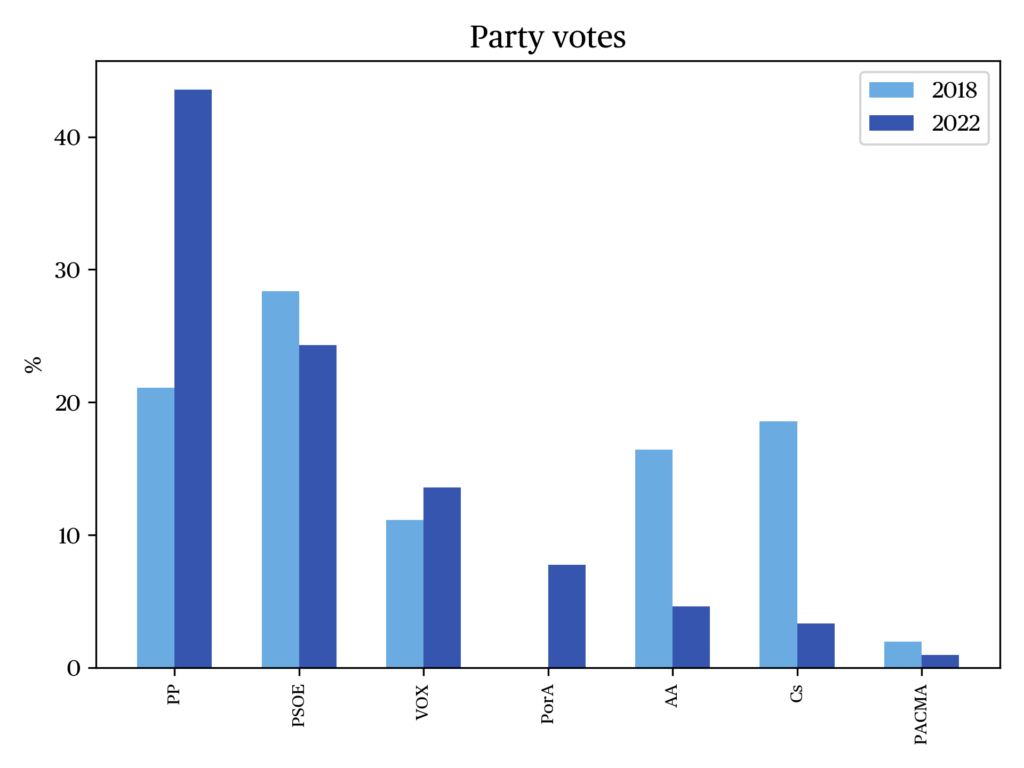

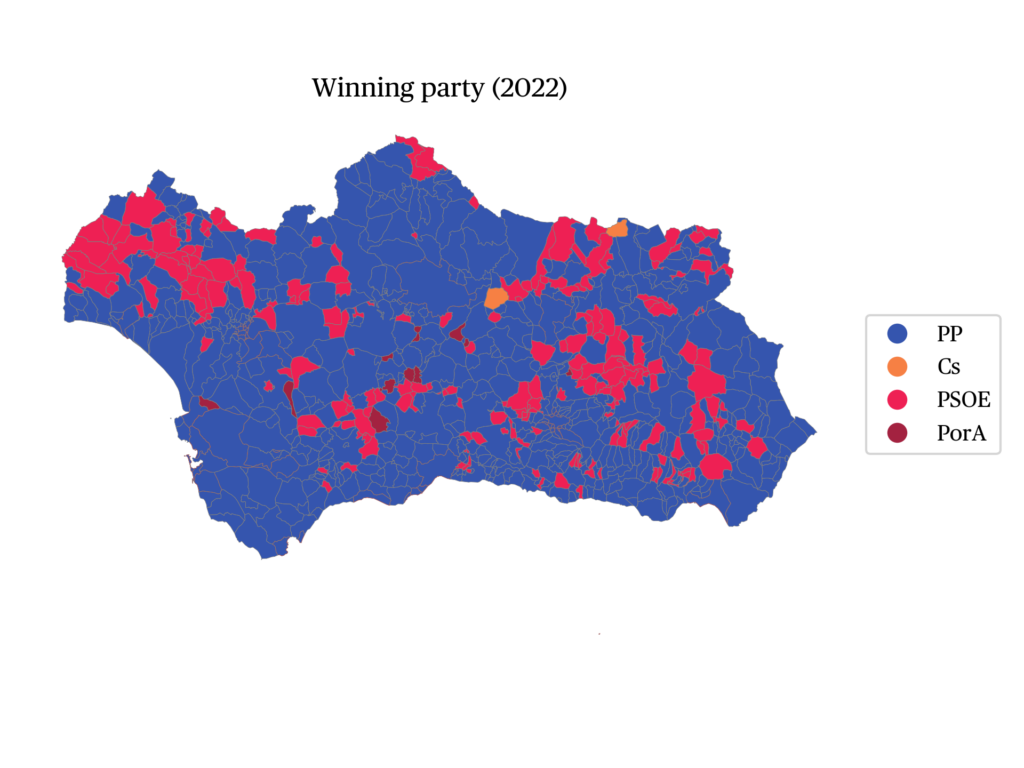

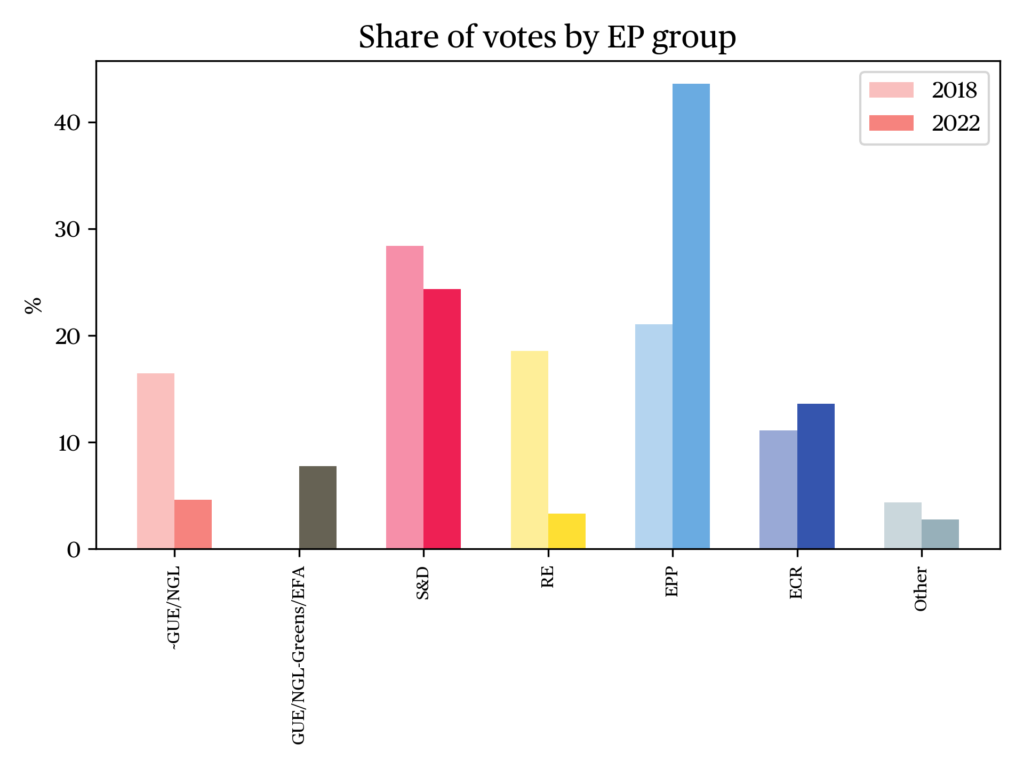

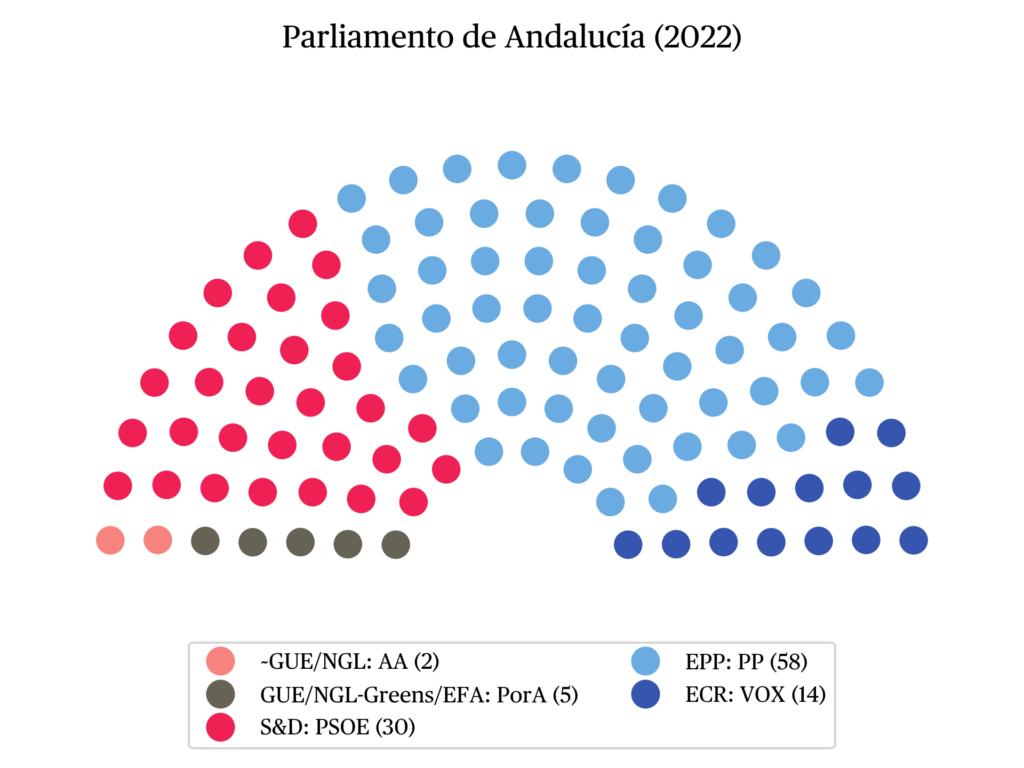

The June 2022 elections in the Autonomous Community of Andalusia resulted in an absolute majority for the PP (Partido Popular), which obtained 43.11% of the vote and 58 of the 109 seats that make up the Andalusian Parliament. These elections also confirmed the decline of the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) in the region: with 24% of the votes and 30 seats, the PSOE lost its historical position as the most voted party in Andalusia.

Electoral system and socio-demographic features of Andalusia

Andalusia is one of the four Spanish regions that have their own electoral calendar, unlike the thirteen other regions that usually hold their elections simultaneously. For this reason, Andalusian electoral contests frequently revolve around specifically regional, rather than countrywide, issues. As in the general elections, the electoral system for the Andalusian elections uses the D’Hondt method with an electoral threshold of 3%. The parties present closed lists in each of the eight provinces. Seats are apportioned among the provinces by population, with the Seville constituency being assigned the most seats (eighteen).

Among the most noteworthy socio-demographic features of Andalusia is its large population, which represents 18% of the total population of Spain according to INE’s 2022 data. As is the case in other Spanish regions, Andalusian provinces are characterized by stark contrasts between rural and urban areas. In addition, several of the Andalusian provinces have among the highest levels of unemployment in the country. In line with these economic difficulties, employment is the main concern of 47% of Andalusians, well before other issues (Andalusian Barometer, September 2022).

On the other hand, Andalusia is a gateway for a high number of immigrants, although it is not the community with the greatest migratory pressure, with many migrants moving to other areas of the country. However, one of its provinces, Almería, has the highest proportion of immigrants Spain-wide (21.78% compared to the national average of 11.62), according to INE data (2022). This is due, in part, to the importance of the agricultural sector. Moreover, together with the Canary Islands, Andalusia is the Spanish Autonomous Community with the lowest GDP per capita. In this context, it is understandable that economic and social issues received special attention from parties, candidates and voters during the last election campaign.

The electoral performance of the PP and the PSOE

The Andalusian electoral process was relevant beyond the regional context, as it confirmed the very positive dynamics of the Spanish Conservatives. A few months earlier, the PP had won the elections in Castilla y León, a traditionally conservative stronghold, where it now governs in coalition with Vox. In Madrid, in 2021, the PP had also celebrated an overwhelming victory in a regional election under the leadership of the president of the Community, Isabel Díaz Ayuso. In addition, in a context of increasing national polarization, this contest was perceived as a test by political parties.

In Andalusia, the polls pointed to another victory for the PP, led by presidential candidate Juanma Moreno. The biggest unknown was whether the PP would need to gather support from other right-wing parties (Ciudadanos and Vox) to form a government, as it had happened in 2018. This apparent uncompetitiveness, coupled with the traditionally low turnout in Andalusia, may explain why only 56% of Andalusian citizens participated in this election. Andalusian electoral contests may also suffer from a lack of mobilizing capacity, due, in part, to their being scheduled independently of other elections.

The PP won in all provinces, beating the PSOE in 70% of Andalusian municipalities. This was a reversal of the traditional voting trend in Andalusia which had seen the PSOE dominate the party system, governing for six terms with a parliamentary majority, for one term with a minority, and for four terms with the support of third parties. However, population size and income level have had a significant impact of the distribution of the vote. The PP has obtained better results in large municipalities and provincial capitals, as well as in higher-income areas. Among the reasons for these results is the transfer of the Ciudadanos vote to the PP, due to two factors: its role as a junior government partner for four years and the erosion of the Ciudadanos brand throughout Spain. On the other hand, the economic situation occupied a large part of the discussions during the campaign. The PP managed to defend its record in office by exposing the decrease in unemployment and the growth above the Spanish average during Moreno’s term. Moreno’s management capacity, together with his image of honesty, are the two factors most frequently wielded by those in Andalusia who voted for the PP in last June’s elections (24.4% and 13.6%, respectively, according to CIS data).

On the other hand, the poor performance of the Andalusian PSOE was the product of a progressive erosion of the three pillars on which its past success was anchored: (1) the culture and political memory of a left-leaning community; (2) its contribution to the modernization of the region while in government, including through the management of European funds earmarked for less developed regions; (3) but also a model of electoral clientelism related to the administration of those funds (Cazorla 1992; 1994). Thus, although from 2012 onwards it continued to govern, first in coalition with Izquierda Unida and then as a minority government, it did so while losing voters (45.5% PP vs. 35.5% PSOE). In the subsequent elections of 2015 and 2018, despite being the most voted party, it suffered a notable decline in support in the polls, eventually losing the capacity of forming a government in 2018.

The PP took advantage of this period to gain ground among urban voters and the middle classes. In recent times, the effects of the 2008 crisis and the chronification of problems such as unemployment, as well as the corruption cases being settled in the courts of justice, added to the decline of the Socialists. In 2011, the so-called “ERE case” was opened, which would not be closed by the Supreme Court until November 2019 and in which, among other important charges, José Antonio Griñán, the former PSOE president of Andalusia (2015-2018), was sentenced to 6 years in prison for prevarication and embezzlement of public funds.

The pre-electoral period saw a confrontation between the autonomous and national leadership of the PSOE. In an attempt to appease tensions, primaries were held to choose the candidate for the 2022 regional elections, a process that only further exposed the division of the party between a centrist wing and another more aligned with the positions of the national left-wing coalition with Unidas Podemos and Izquierda Unida. The winner of these primaries was Juan Espadas, the favorite candidate of the national leadership who, despite being mayor of Seville, failed to be known and connect with the electorate of the autonomous community. From that moment on, the socialist campaign focused on the threat of Vox becoming part of a future PP government, a scenario which the polls had made credible; this message, which appealed to the past, was shared by other left-wing parties. But the PSOE’s electoral narrive proved rather ineffective; in fact, it may even have favored the PP by making it appear a more centrist, moderate and efficient alternative to the radicality of a potential PSOE government.

Other political parties across the ideological spectrum

Besides the PSOE, other left-wing parties also went to the polls, and the left showed signs of fragmentation. Despite the opening of a negotiation process, Adelante Andalucía (AA) did not to join the Por Andalucía (PA) coalition, instead pursuing its own anti-capitalist, Andalusian agenda. The party has never exercised governmental functions along with the PSOE in Andalusia in the past; nor did it exercise it at the national level in the post-pandemic context. This distinctive factor, however, took a back seat with the accentuation of anti-fascist sentiments caused by the scores of Vox in the polls and the rise of a radical Andalusianist discourse in the party’s rhetoric.

Finally, AA would obtain two seats in the regional parliament: one for the Seville constituency, the largest, and another for Cádiz, where the party governs the capital of the province. As was the case for PA, these elections were experienced as part of the struggle for the leadership of the left, with a view to the next general elections. In the choice of the candidate, the configuration of the electoral lists and, later, the development of the campaign, Unidas Podemos and, in particular, its ministers in the national government, were marginalized in the face of IU and PCE ministers, such as Alberto Garzón and Yolanda Díaz. As for the content of their campaign, they exploited not only the fear of the radical right, but also the social policy achievements of the central government, in which the left and PSOE were associated. This claim did not prevent the PSOE from dropping from 17 to 6 seats. The debacle of the left in Andalusia was blatant.

Besides the PP, other center and right-wing parties participated in the election. In the 2018 elections, the center was represented by Ciudadanos, which entered the government as the PP’s junior partner, with the regional leader of the party, Juan Marín, serving as its vice president. The party and its leader thus established their presence and in the community. However, as of 2022, the party had become increasingly marginalized, and its representatives had been losing their seats from regional parliaments all over Spain following its resounding failure in the general elections of November 2019. The party had lost 37 seats and 3 million votes Spain-wide compared to the previous national elections held eight months earlier. As pre-electoral polls had anticipated, the Andalusian election was no exception for Ciudadanos in this regard. The expected transfer of votes to the PP was even reinforced by Marín’s campaign strategy. The Ciudadanos leader defended the record of an executive of which he had been a member, but which was led by the PP. In the electoral television debate, the candidate of Ciudadanos was the only one who did not ask Moreno Bonilla the uncomfortable question: Would Vox enter a hypothetical PP government? In the end, Ciudadanos was left without representation in the Andalusian Parliament.

Vox, which had become the great protagonist of the campaign thanks to the left’s narrative, aimed to grow electorally in the community from which it had emerged nationally in 2018. To this end, the party was betting on being essential to form a government, which would have provided it with greater negociation leverage. The first objective was met, although not to the extent expected at the beginning of the campaign: Vox obtained two additional representatives, reaching fourteen seats. The second objective failed due to the PP’s achievement of an absolute majority. This led Vox to interpret the result as a defeat to be followed by a review of the failures of the campaign, and the election triggered an internal crisis. Among other issues, the party had to improvise an electoral program when the media criticized its lack of a project for the community. It chose to present a candidate with a national profile, Macarena Olona, who did not have roots in Andalusia. In addition, the campaign was highly personalized and ideologized, with the candidate trying to force her PP counterpart to recognize the role that Vox would play in a future government. After the failure of this strategy, Olona resigned from her position as a member of parliament for Andalusia, initiating a public drift away from Vox. The Andalusian autonomous process made it clear that, while part of the electorate is receptive to radical right-wing discourses, the party faces dilemmas when trying to grow at the regional level despite its highly centralized structure.

The year 2023 in the polls

The Andalusian elections of 2022 were the last elections to be held in Spain until the municipal and regional elections of 2023. There will also be general elections, foreseeably in the last quarter of 2023. The low nationalization of Spain’s party system, with nationalist and regional cleavages, issues and parties, makes it difficult to make projections based on a single regional election. However, it is likely that at least at the national level, two trends registered in the Andalusian elections will be repeated. On the one hand, the fragmentation of the non-socialist left into parties or coalitions with both nationwide presence and multiple local brands, as in this case of AA, is likely to persist. On the other hand, the struggle for right-wing votes between the PP and VOX will probably continue: the Popular Party seems to attract former Ciudadanos voters and have the capacity to articulate a liberal management model as an alternative to the social-democratic one, a strategy that appeals to the moderate electorate.

References

Barómetro de Opinión Pública de Andalucía (2022). Centro de Estudios Andaluces, septiembre 2022.

Cazorla, J. (1992). Del clientelismo tradicional al clientelismo de partido. Institut de Ciencies Politiques i Socials, Working Papers, n. 55, Barcelona.

Cazorla, J. (1994). El clientelismo de partido en España ante la opinión pública. El medio rural, la administración y las empresas. Institut de Ciencies Politiques i Socials, Working Papers, n. 86, Barcelona.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) (2022). Cifras de población.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE) (2022). Estadística del Padrón Continuo. Datos provisionales a 1 de enero de 2022.

Postelectoral elecciones autonómicas (2022). Comunidad Autónoma de Andalucía. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

citer l'article

Leticia M. Ruiz Rodríguez, David H. Corrochano, Regional election in Andalusia, 19 June 2022, Mar 2023, 94-97.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue