Regional election in Bavaria, 8 October 2023

Melanie Walter-Rogg

Professor of political science at the University of RegensburgIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Melanie Walter-Rogg

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

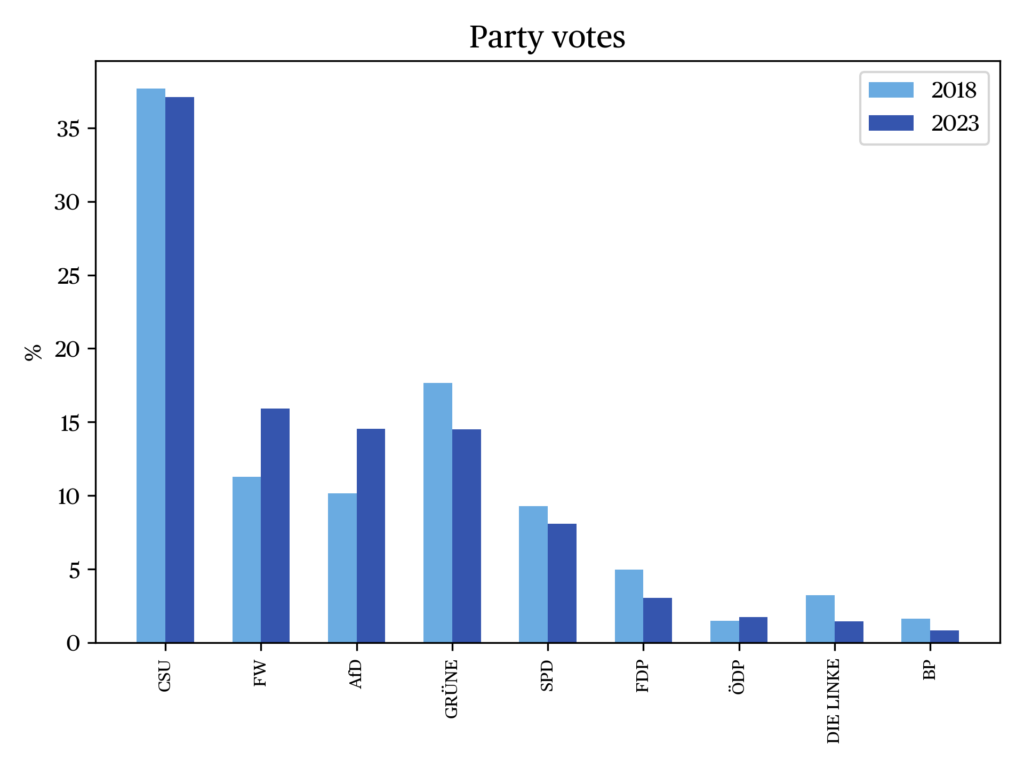

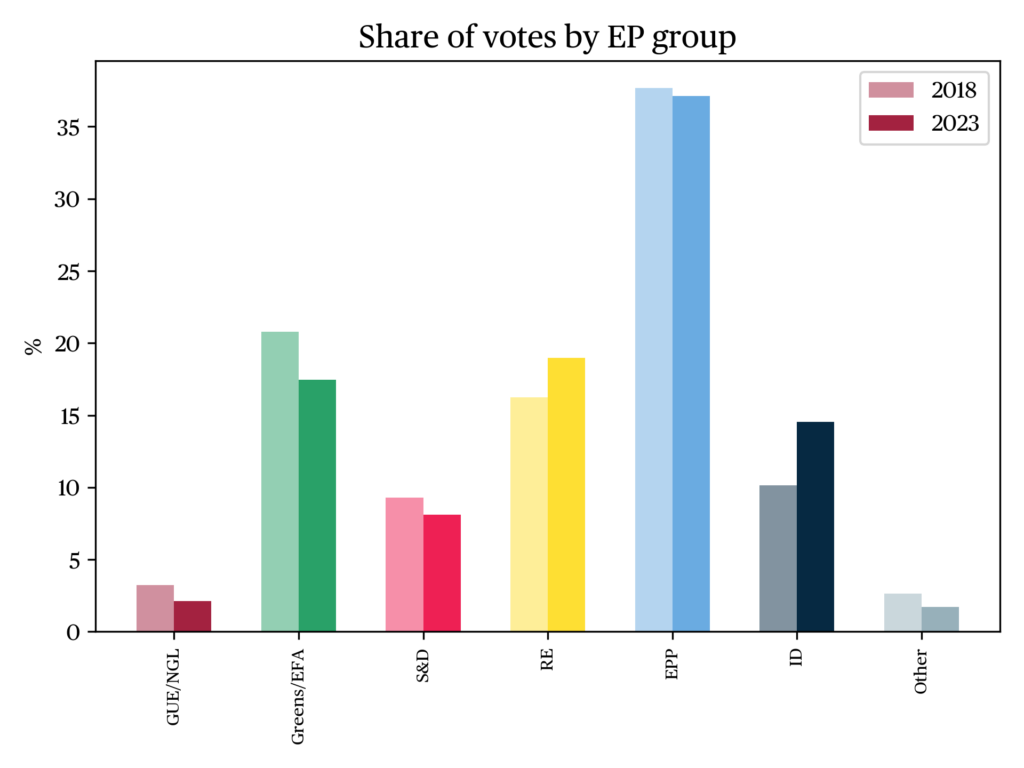

A new Landtag was elected in the Free State of Bavaria on 8 October 2023. CSU leader and Minister President Markus Söder and his deputy and Minister of the Economy Hubert Aiwanger (Free Voters), who have led a “black-orange” coalition since 2018, also stood for election as the leading candidates of their respective parties in 2023. Although the Christian Social Union hoped to be able to form a single party government again, as they did in 2013, the forecasts for the 2023 Bavarian elections indicated early on that this would not be possible (Zicht & Cantow, 2023). Therefore, both politicians stated during the election campaign that they wanted to continue the coalition. This was despite events such as Hubert Aiwanger’s heavily criticised speech in Erding and the so-called leaflet affair in the run-up to the Bavarian elections, which put a heavy strain on the governing coalition. Due to the generally poor mood and dissatisfaction with the “traffic light” government in Berlin, the two state elections in Bavaria and Hesse in October 2023 were highly anticipated. Although some analysts have noted an increasing autonomy of the regional party sections in defining their electoral strategies (cf. Detterbeck et al., 2008), a strong influence of German federal politics was already evident in the 2018 Bavarian election due to the dominance of the immigration issue and the associated internal party disputes within the CDU/CSU (Albrecht and Walter-Rogg, 2023). Federal politics were also very likely to have an impact on the state elections in Bavaria and Hesse in 2023 due to the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, rising inflation and the increasingly controversial issues of migration and climate change. In June 2023, the popularity of the federal government fell to its lowest level since the start of the coalition in December 2021 as various challenges and crises unfolded (DeutschlandTrend, 2023). Almost 80 percent of respondents stated that they were rather not or not at all satisfied with the work of the federal government. The CSU was therefore hoping for a significant gain compared to the Bavarian state elections in 2018, in which it lost 10.5 percentage points and fell to a historic low of 37.2 percent. However, in Bavaria, the Free Voters and the AfD benefited considerably more from the political mood in Germany than the CSU. The situation was different in the federal state of Hesse. Although the traffic light parties also lost a significant amount of votes there, the Hessian CDU was able to capitalise on these losses to increase its vote share by 7.6 percentage points, while the Bavarian CSU remained at the same historically low level as in 2018. The fact that the clocks tick a little differently in Bavaria than in the rest of Germany is also demonstrated by the fact that the Free Voters won 15.8 per cent of the total vote in Bavaria, while the party failed to enter the state parliament in Hesse. Furthermore, unlike in Hesse, the Bavarian FDP did not make it into parliament, gathering only 3 percent of the vote.

Election results

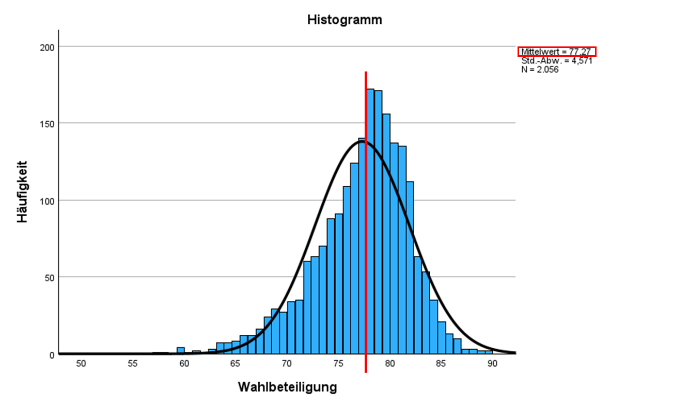

In the election to the 19th Bavarian state parliament, 73.1 per cent of around 9.4 million eligible voters cast their vote. Looking at the average distribution of voter turnout across all 2,056 Bavarian municipalities, the median value is 77.3 per cent. The left-hand distribution in Figure a shows a left-skewed and right-steeped distribution, i.e. fewer municipalities tend to have a low voter turnout and more municipalities tend to have a higher voter turnout. The right-hand distribution in Figure a shows that the centre of the distribution (the middle 50 percent of municipalities) has a voter turnout of between 75 and 80 percent (blue box). A quarter of municipalities are below this with a turnout of 58 to 74 percent and another quarter are above this with a turnout of 81 to 90 percent. There are only a few municipalities that are far above or below this level. For example, the small towns of Stadelhofen and Wattendorf have a turnout of just under 90 per cent and only in some cities such as Schweinfurt (59.3%), Hof (62.7%) or Neu-Ulm (62.8%) and some rural municipalities such as Reichenbach (57.6%) in the Upper Palatinate or Bruckberg (58.3%) in Lower Bavaria is the turnout in the 2023 Bavarian elections significantly below average.

Figure a · Voter turnout in the 2023 Bavarian elections at municipal level

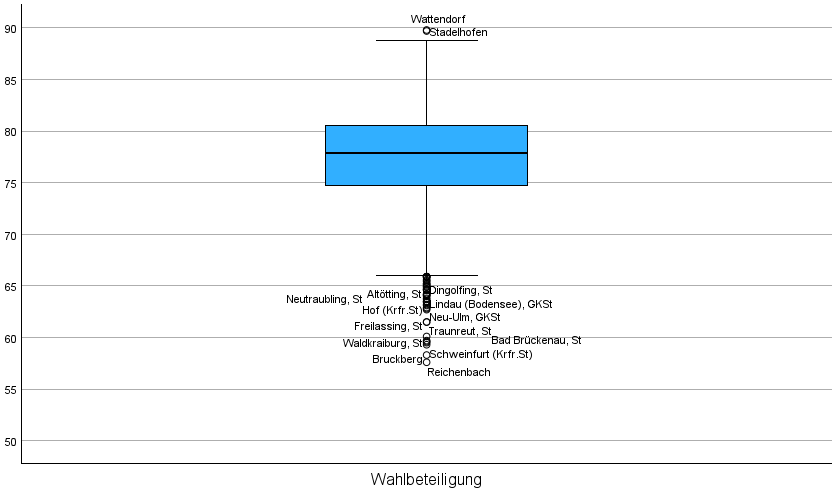

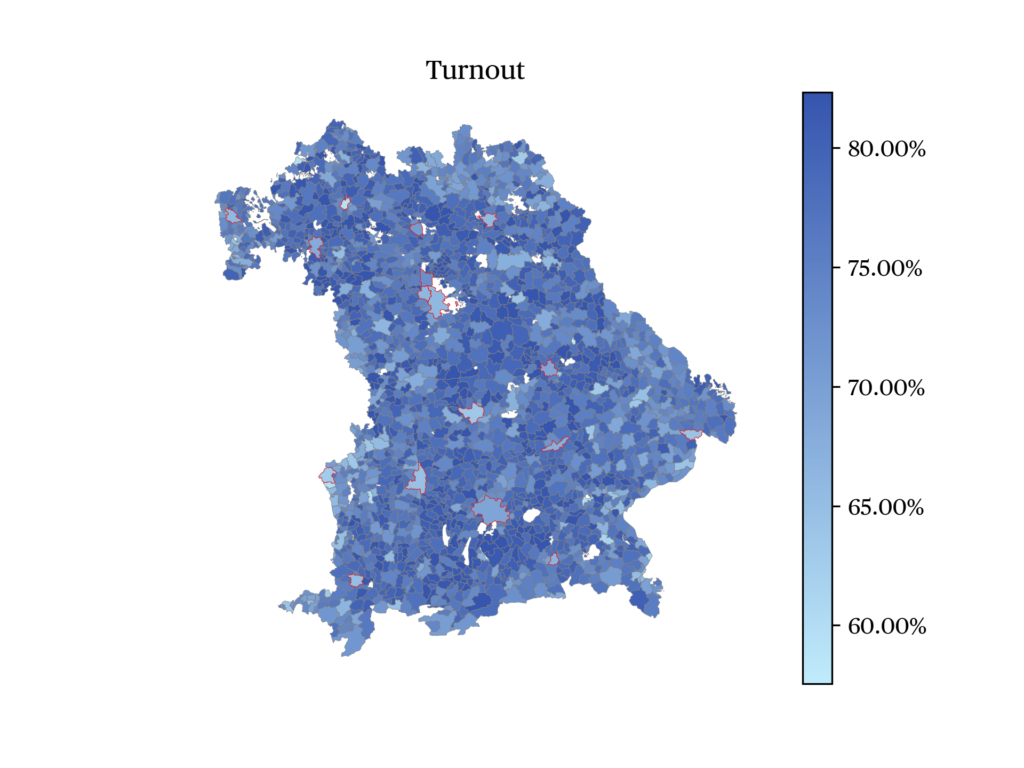

The regional distribution of voter turnout in the 2,056 Bavarian municipalities shows no clear pattern (see Figure b). However, a clear correlation (R2=.28) between municipality size and voter turnout can be seen in the dot chart: The larger a municipality, the lower the turnout in the 2023 Bavarian election. For example, in the state capital of Munich, which has the highest number of eligible voters (910,084), voter turnout is only 69.1 percent. The eight largest cities in Bavaria (Munich, Nuremberg, Augsburg, Regensburg, Würzburg, Ingolstadt, Fürth and Erlangen) have the lowest average voter turnout (67.4 per cent) compared to the other types of cities and municipalities (see figure c), while the 1,325 small rural municipalities have the highest turnout (78.4 per cent).

| Municipality type | Average | Standard deviation | N |

| Large city | 67.4 | 2.95 | 8 |

| Middle-sized city | 68.8 | 4.71 | 81 |

| Larger small city | 73.7 | 4.23 | 150 |

| Smaller small city | 77.0 | 4.39 | 492 |

| Rural municipality | 78.4 | 3.78 | 1,325 |

| Bavaria | 77.3 | 4.57 | 2,056 |

Figure c · Voter turnout in 2023 sorted by type of city or municipality

In 2018, the Bavarian elections had mobilised significantly more registered voters than in previous years. Back in 1990, only two thirds of those eligible to vote in Bavaria, which was at the time characterised by a three-party system with a clear CSU dominance, had in fact cast their ballots. The lowest turnout rate in Bavaria, at just 57.1 percent, was reached in 2003, when the erosion process of the Bavarian social democracy began and many of its supporters no longer participated in elections. In 2008, the CSU lost significant support from its traditional electorate following severe internal party disputes, and the turnout remained low at 57.9 percent. However, Bavarian voters increasingly realised that other parties could also govern with the CSU (Kahrs, 2018: 18). When the political spectrum expanded to include the AfD in 2018, turnout rose to 72.3 percent and remained at this level in 2023 (+1 pp). Thurner et al. (2023: 35) showed that while the AfD was particularly successful at mobilising previous non-voters in Bavaria in 2018, the Greens, the Free Voters and new small parties such as Volt or Mut also managed to attract former non-voters. Infratest dimap’s voter flow survey for the 2023 Bavarian elections (Tagesschau, 2023) shows that the CSU also managed to mobilise 180,000 non-voters this time. The party also won back 140,000 voters from the Greens, 80,000 from the SPD and 90,000 from the FDP. However, the CSU suffered major losses to the Free Voters (-260,000) and the AfD (-110,000). As a result, the CSU remains by far the strongest party, but with 37 percent obtains its weakest result since 1950 (28%) and, as a consequence, its share of the vote from five years earlier hardly changes (-0.2 pp, see “the data”).

By contrast, the Greens – joint winners with the AfD in the 2018 Bavarian elections – suffered significantly losses, only achieving 14.4 percent (-3.2 pp). The SPD obtained its worst result in any West German state with just 8.4 percent (-1.3 pp). While traditionally, the Social Democrats do poorly in Bavaria, another single-digit election result is an embarrassment even by Bavarian standards, especially with an SPD chancellor leading the federal government. With 3 percent (-2.1 pp), the FDP fell well short of the 5 percent threshold, losing its most votes to the CSU (-90,000), the Free Voters (-50,000) and the AfD (-40,000). About 20,000 former voters of the small liberal party did not vote this time or moved to a different party (see Tagesschau, 2023).

At the mid-point of the federal government’s term, the mood of its member parties is therefore rather gloomy. The clear election winners in Bavaria are the Free Voters and the AfD, which became the second and third strongest parties, respectively. The Free Voters increased their vote share by 4.2 percentage points to 15.8 percent and managed to win their first two direct seats in Germany. The AfD gained 4.4 percentage points to reach 14.6 percent. In the village of Oberrieden (population 1,200) in the Kaufbeuren constituency, the AfD even became the strongest party with 31.3 percent. The CSU lost 15.7 percentage points there and only received 28.2 percent of the total vote. All other parties together held 6.6 percent (-1.9 pp) of the vote in the 2023 state election.

While political scientist Werner Weidenfeld sees the “punishment of the traffic light parties” (see Schmid, 2023) as the main message of the Hesse election, the reasons behind the Bavarian election result are more complex. Here, confidence in the ruling coalition and regional Minister President Söder was also a significant factor. The incumbent head of government Markus Söder was assessed significantly more favourably than in the 2018 Bavarian election campaign. While only 61% of citizens saw him as a good Minister President in September 2023, five years earlier, only 49% of respondents held that same opinion. At the same time, 47 percent of eligible voters were dissatisfied with the work of the Bavarian Minister President and his state government shortly before the 2023 Bavarian elections (Infratest dimap, 2023). As in 2018 (Bukow, 2018; Albrecht and Walter-Rogg, 2023), in 2023 the Bavarian election was also marked by the influence of the parties’ popularity at the federal level as well as by federal political issues, with regional issues playing a lesser role. In contrast to the previous five years, the 2023 Bavarian election took place under “historically new circumstances” (cf. Hummel 2023: 6). Even in wealthy Bavaria, the Covid-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine, rising inflation and the increasingly controversial topics of migration and climate impacted many peoples’ life. In Bavaria, 58 percent of citizens still considered the economic situation to be good shortly before the election, 31 percentage points less than before the 2018 state election (see Schwesinger, 2023).

Initially, the election campaign in Bavaria promised little suspense. In the summer, however, the opinion ratings of the member parties of the federal coalition deteriorated significantly. Issues such as the new “heating bill” and the shortcomings of the migration and refugee policy were also the subject of heated debate in Bavaria. The leaflet affair against Hubert Aiwanger also began at the end of August, jeopardising the continuation of the governing coalition that had been announced by both sides. However, in the end, just under 53 percent of voters opted for political continuity by supporting the black-orange alliance. Although the CSU emerged from the election weakened and the Free Voters and their leader significantly strengthened, 57 percent of voters preferred Söder as head of government for the future coalition. Söder was also the preferred candidate for Minister President of many Free Voters and AfD supporters. Nevertheless, the 2023 state election confirmed that the exceptional position of the CSU as the dominant political force of Bavarian politics is a thing of the past. Before the election, 51 percent of eligible voters stated that the CSU had “lost its sense of what really moves Bavarians” (FGW, 2023b). This development gave the Free Voters and the AfD the opportunity to attract disappointed voters. The AfD was also helped by the fact that the topic of asylum and migration clearly increased in prominence in the late summer of 2023 and the mood in Bavaria changed dramatically. While more than two thirds of eligible voters (68%) still believed that Bavaria could cope with the large number of refugees in 2018, this share had shrunk to 37 percent at the beginning of October 2023 (FGW, 2023b). The CSU is still considered to have the highest competence in almost all important policy areas (including the “economy”, the “future” of the region and “education”). However, while the CSU has lost significant ground in Bavaria compared to 2018, the Free Voters have made gains. Apparently, Hubert Aiwanger and his party are also succeeding in deterring voters from voting for the AfD. Indeed, 39 percent of Free Voter supporters say that they would vote for the AfD in Bavaria if it were not for this party. The Greens remained ahead on the second most important issue in the Bavarian election – “climate protection” – although 42 percent of Bavarians think that the current climate protection measures go too far, including a large number of AfD voters (Infratest dimap, 2023b).

Geographical and socio-demographic trends

In the seven administrative districts, it can be seen that the CSU’s share of the vote varies only slightly between 32 (Lower Bavaria) and 42 percent (Lower Franconia) (Figure d). The AfD has now also managed to achieve between 11 (Upper Bavaria) and 18 percent (Lower Bavaria, Upper Palatinate) in all constituencies (Bavarian State Statistical Office 2023). The Free Voters clearly have their main focus in Lower Bavaria (30%), as their chairman Hubert Aiwanger represents the Landshut constituency. In contrast, the party received the fewest votes in Middle and Lower Franconia (9%/12%). In the other districts, their share varies between 14 and 18 percent. The Greens received the most votes in Upper Bavaria (19%) and Middle Franconia (17%) and the fewest votes in Lower Bavaria (7%) and Upper Palatinate (9%). The SPD received only 8 to 11 percent of the vote in all constituencies, but the least in Lower Bavaria (5%).

| CSU | FW | AfD | Greens | AfD | |

| Niederbayern | 32 % | 30 % | 18 % | 7 % | 5 % |

| Oberpfalz | 39 % | 18 % | 18 % | 9 % | 8 % |

| Schwaben | 36 % | 17 % | 17 % | 13 % | 7 % |

| Bayern | 37 % | 16 % | 15 % | 14 % | 8 % |

| Oberfranken | 40 % | 15 % | 17 % | 10 % | 10 % |

| Oberbayern | 35 % | 14 % | 11 % | 19 % | 8 % |

| Unterfranken | 42 % | 12 % | 16 % | 14 % | 9 % |

| Mittelfranken | 40 % | 9 % | 14 % | 17 % | 11 % |

| Bavaria | 37 % | 15,8 % | 14,6 % | 14,4 % | 8,4 % |

Figure d · Election result of the 2023 Bavarian elections per constituency

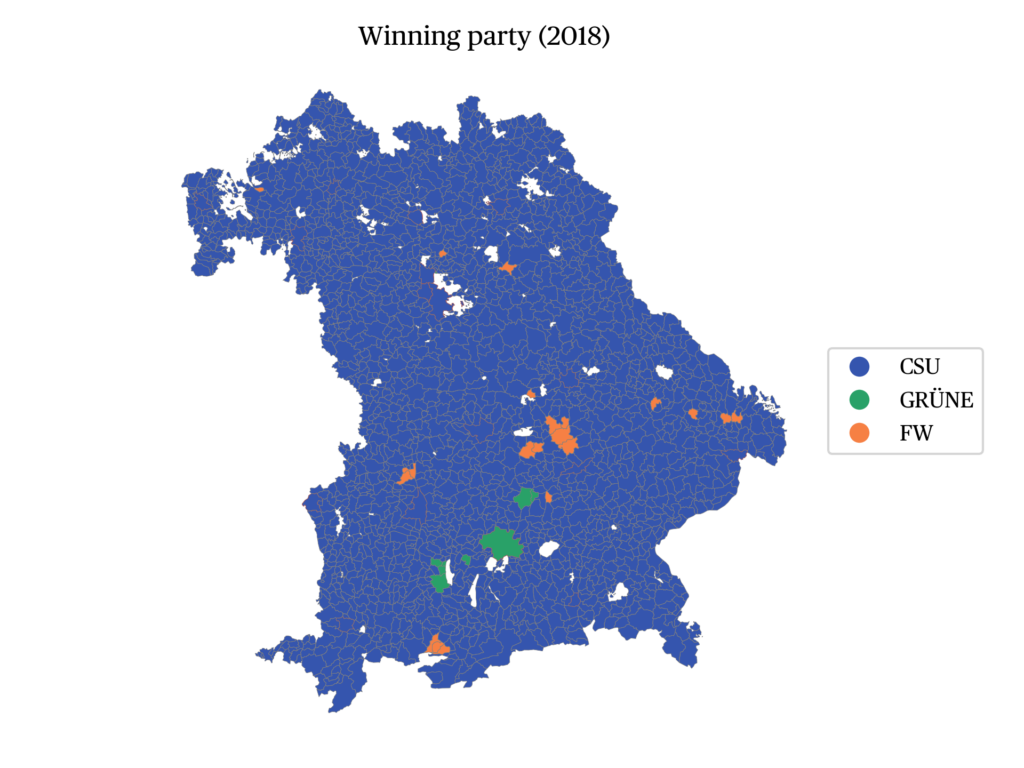

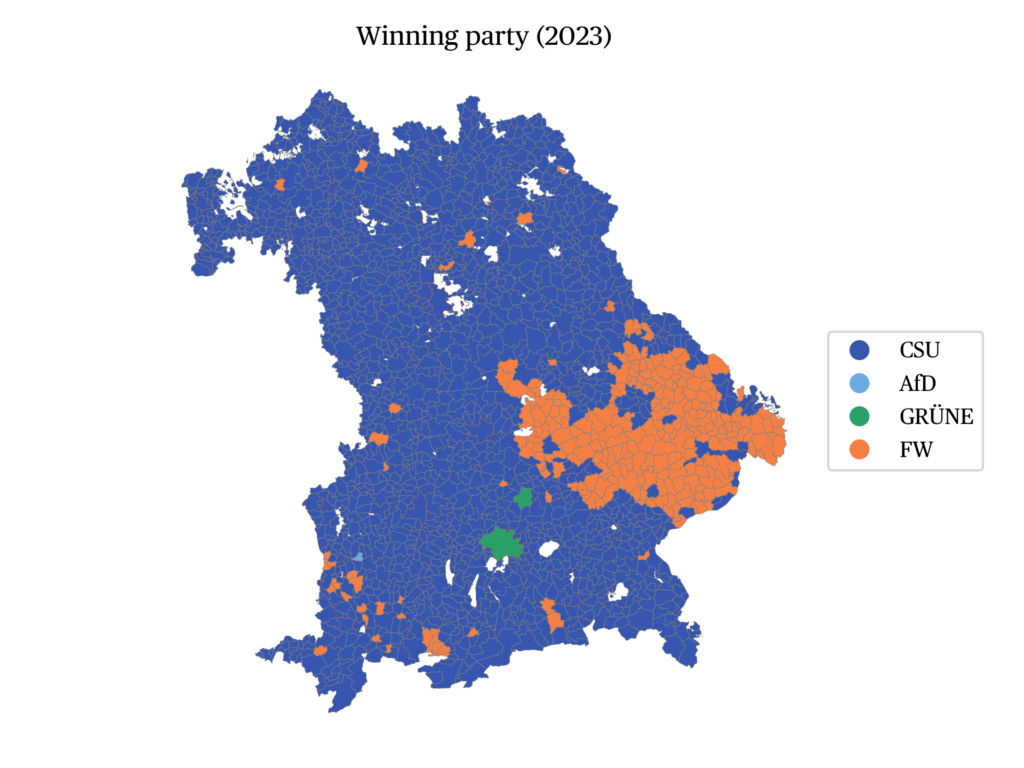

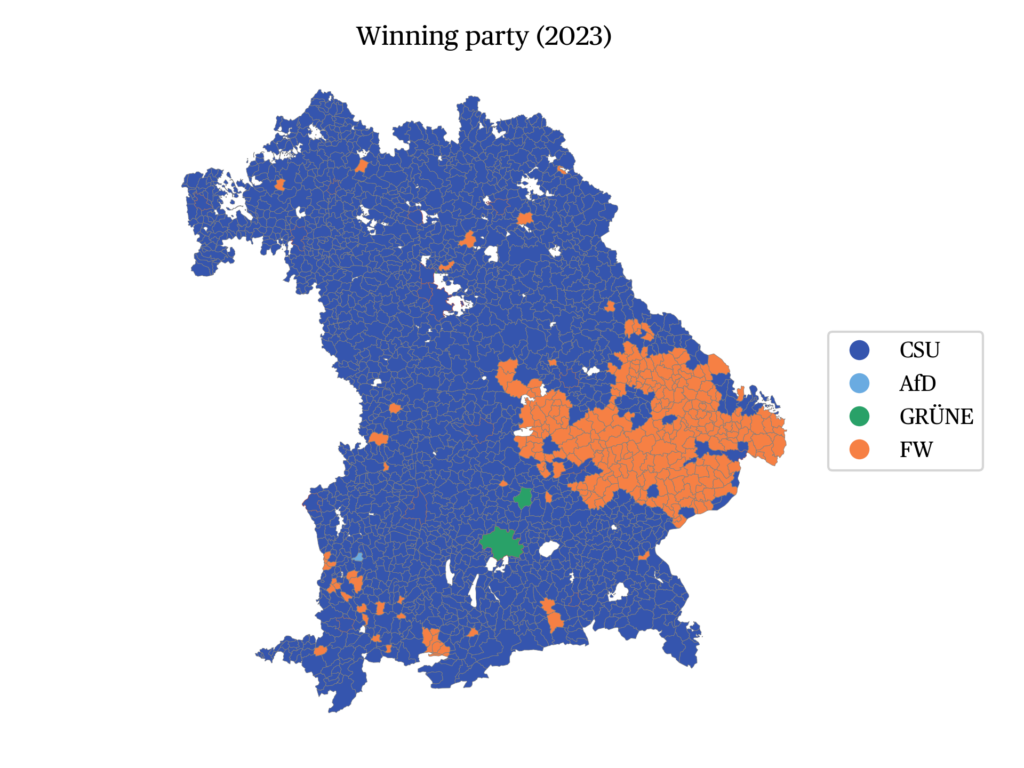

The CSU clearly remains the strongest force in most Bavarian municipalities, even if its dominance has waned since the 2018 state elections (Figure e). The CSU achieved its best statewide result in Bad Kissingen with 48.4 percent, in Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz with 47.4 percent and in Hof with 46 percent. The party was also strong in the constituencies of Bamberg-Land (45.3%), Tirschenreuth (44.6%) and Aschaffenburg-Ost (44.1%). Markus Söder won the direct seat in Nuremberg-East with 41.4 percent (overall CSU vote: 39.2%) and will be a member of the next state parliament. The CSU achieved its worst result in Munich-Centre with 17.7 percent. The Greens had their best result there with 44 percent and top candidate Ludwig Hartmann was able to defend his direct seat with 44.6 percent. The Greens’ top candidate Katharina Schulze also managed to win a direct seat in the Munich-Milbertshofen constituency (35.3 per cent). The worst result for the Greens was in Regen in eastern Bavaria (4.3%). Overall, it can be seen that the CSU, AfD and Free Voters performed significantly better in small municipalities and smaller towns than in large cities, while the reverse is true for the Greens.

Figure e · Winning parties in the 2018 and 2023 Bavarian elections

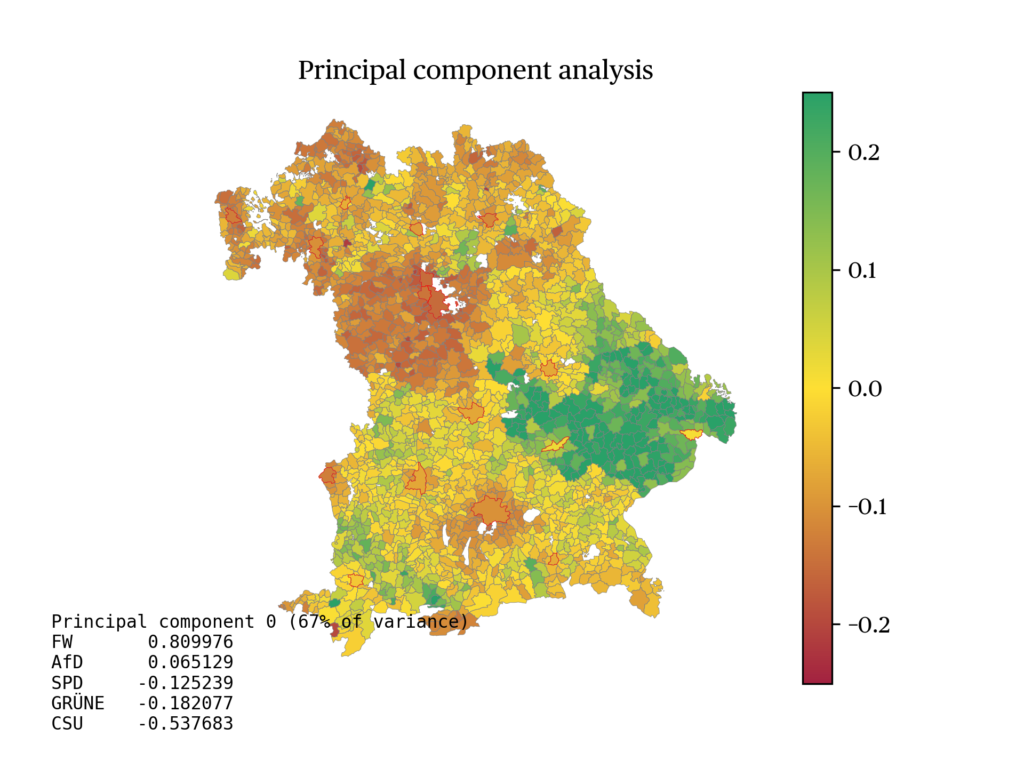

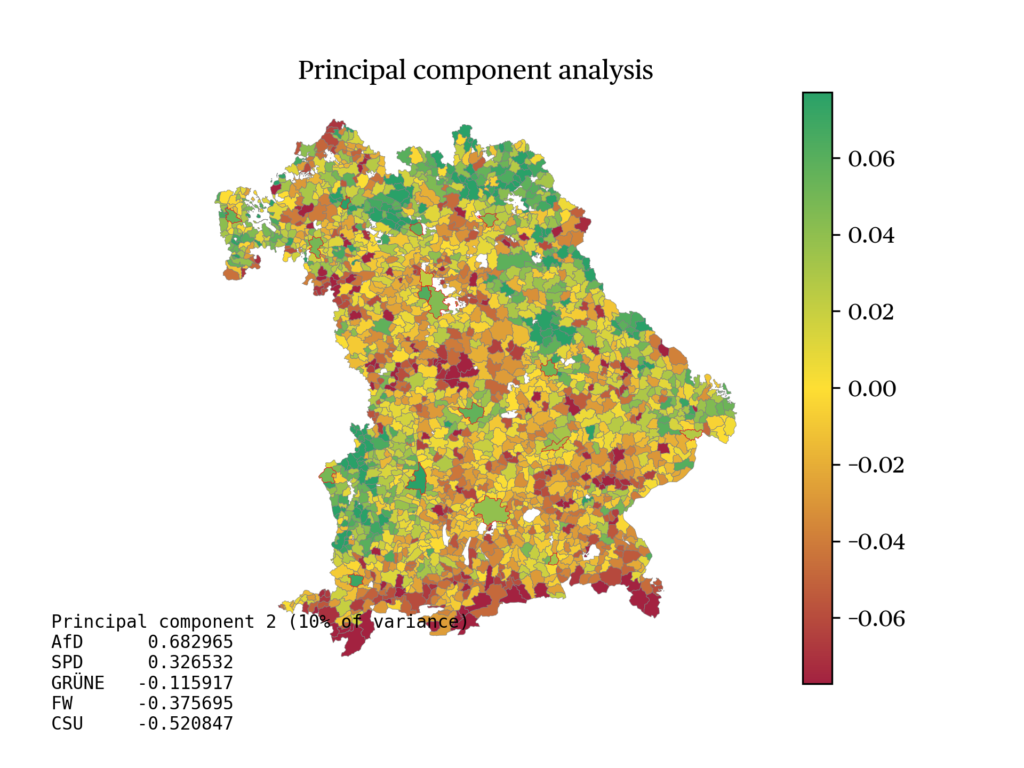

Figure f shows the regional voting behaviour using a principal component analysis of the 2023 election results. The first factor, which explains 67% of municipality-level variance, illustrates the regional focus of the Free Voters in Lower Bavaria and the Upper Palatinate. The greener a municipality, the more voters cast a ballot for the Free Voters and the less likely they are to vote for the CSU, SPD or Greens. In Bavaria, the Free Voters are an established political force – especially in the more rural regions, of which there are many in Germany’s largest federal state by area. Once again, the Free Voters obtained their best results in small municipalities, where they made further significant gains. In large cities, on the other hand, the Free Voters are very weak. The party obtained its best results where its top candidate Hubert Aiwanger was running: Aiwanger won the direct seat in his constituency of Landshut with 37.2 percent, while the Free Voters achieved 32.5 percent. The orange party was also strong in Neuburg-Schrobenhausen (31.6 per cent), Forchheim (27.6 per cent), Mühlheim am Inn (25.3 per cent), as well as Dingolfing and Rottal-Inn (24.9 per cent).

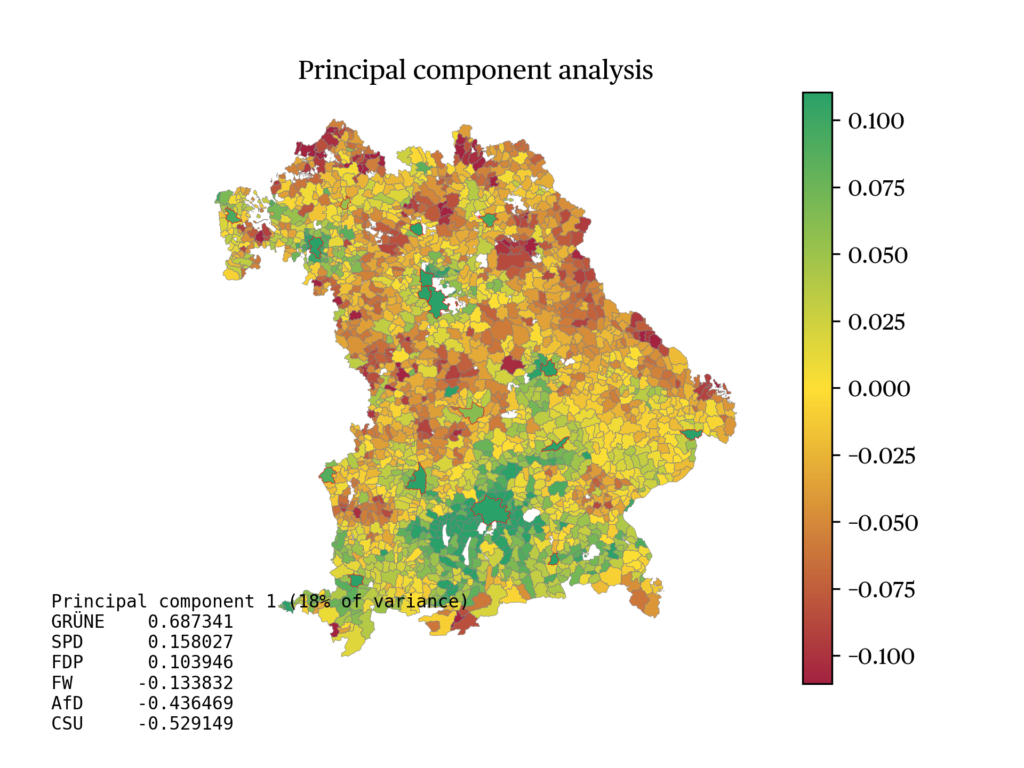

On the 2nd factor, which explains 18% of municipality-level variance, we see the strongholds of the Greens. In these municipalities, fewer people vote for the CSU, the AfD or the Free Voters. The third factor, explaining 10% of the variance, shows municipalities with a relatively high AfD share where the CSU, the Free Voters and the Greens attracts less votes. The AfD achieved its best result in the Günzburg constituency, where it received 23 percent of the vote, while its worst result was in Munich-Centre with 4.5 percent. In the municipality of Oberrieden in the constituency of Kaufbeuren, the AfD was the strongest party with 31.3 per cent. The AfD politician Gerd Mannes achieved the most direct votes in Günzburg with 24.4%, placing second behind the CSU’s Jenny Schack (35.6 %). Munich-Centre is the only constituency in which the AfD scored below the 5% threshold, with 4.5% of the total vote. The AfD increased its vote share in all Bavarian constituencies, in some cases by almost nine percentage points. No other party represented in the Bavarian state parliament saw a similar increase. In 24 of the 91 constituencies, the AfD even managed to become the second largest party. These are results that would have been inconceivable for the right-wing populist party just a few years ago, even in eastern German states.

The SPD obtained its best results in Nuremberg-North with 13.5 percent and its worst result in Regen in the county of Freyung-Grafenau with 3.8 percent. In Coburg and Munich-Mibertshofen, the SPD received 13.3 percent of the vote. Its electoral performance was also above average in Fürth (13.1 per cent), Schweinfurt (12.9 per cent) and Wunsiedel, Kulmbach (12.9 per cent). The FDP was most successful in Munich-Schwabing, where the Liberals won 9.2 percent; their worst result was in Cham with 1.4 percent. The Left Party achieved its best result in Nuremberg-North with 4.2 percent and its worst result in Deggendorf with 0.7 percent.

According to analyses by Forschungsgruppe Wahlen (2023), gender, age, education and occupation have an influence on voting decisions. Women voted slightly more for the CSU (38%) and the Greens (16%), but less for the AfD (12%) compared to men (36%/14%/17%). As usual, the basis for the CSU’s success lies with the older generation: among the over-60s, the CSU scores 47 percent, while among the under-30s, the CSU is only relatively close to the Greens (23% and 20% respectively). Interestingly, the AfD performs relatively strongly among the under-30s (16%). The Free Voters have similar results in all age groups, but lose support as the level of formal education of voters increases. The latter also applies to the CSU and the AfD. While 44 percent of voters with a lower secondary school qualification vote for the Christian Social Party, only 30 percent of voters with a university degree do so. The right-wing populists have a 19 percent share in the lower education groups and only 7 percent in the group with a university degree. The SPD has a similarly low share of the vote in all education groups, slightly more in the civil servant occupational group. While the CSU is supported equally by all occupational groups, the Free Voters are mainly supported by blue-collar workers (19%) and the self-employed (18%), the Greens by civil servants (20%), the self-employed (18%) and white-collar workers (17%) and the AfD by blue-collar workers (23%).

The building of a coalition government

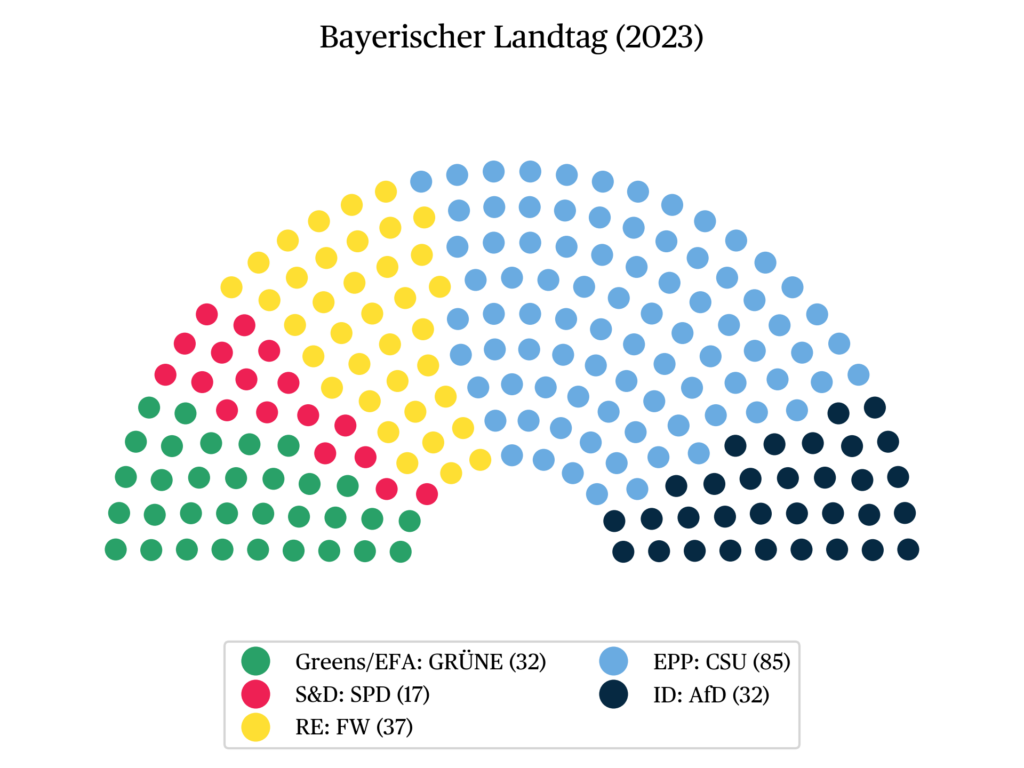

After losing its absolute majority in 2018, the CSU needed a coalition partner. As the FDP had hardly cleared the 5% hurdle, the CSU had to choose between the Greens (17.6%) or the Free Voters (11.6%). The agreement with the ideologically much closer Free Voters was reached quickly and easily. In the election campaign for the 2023 Bavarian elections, the CSU and Free Voters leaders Söder and Aiwanger stated early on that they were willing to continue to govern together (Heim 2023); this was well received by the public. In September, 51 percent rated the black-orange cooperation as very good or good and preferred such a government to a CSU single-party government (63% against) or a black-green coalition (71% against, see Infratest dimap 2023). A CSU single-party government was not deemed likely by any poll in 2023, and the CSU would have had to improve its performance significantly in the last weeks of the campaign to be able to achieve an absolute majority. This time, Minister President Markus Söder had clearly ruled out a coalition with the Greens. In May, he said on Markus Lanz’s TV talk show that “the Greens are a disappointment in the traffic light” and would be more concerned about their “old party ideology” than the “common good of the population” (Rappsilber, 2023). All efforts on the part of the FDP were also rejected by the CSU. In connection with Hubert Aiwanger’s leaflet affair, FDP lead candidate Martin Hagen argued that the Bavarian head of government could not afford a deputy “who has brown stains on his CV and refuses to deal with them honestly and self-critically”. He therefore claimed that “a conservative black-yellow alliance” would be best for Bavaria (Zeit Online, 2023). The fact that the FDP was considering such an alliance was rather surprising. After their only government coalition to date with the CSU, the Liberals were severely punished by voters and did not make it back into the Bavarian state parliament in the 2013 election. In 2023, it was apparent early on that the strong criticism of the traffic light parties made it doubtful whether the FDP would enter the Bavarian state parliament again. It was this very weakness of the Liberals that led Markus Söder and Hubert Aiwanger to repeatedly state that they wanted to continue their government alliance. Following the Bavarian elections on 8 October 2023, the two parties, which together held 122 out of 203 seats (60.1%, see “the data”), presented their coalition agreement after just 19 days. However, the CSU had previously demanded a clear commitment to democracy from the Free Voters and their chairman Hubert Aiwanger: “A lot happened during the election campaign. Simply forgetting about it or saying ‘let’s see’ is not enough,” Söder said after the firs t meeting of the CSU parliamentary group in the state parliament. It had to be clarified if the Free Voters were still committed to stability and “firmly rooted in the democratic spectrum” or if there were other tendencies in their rows. The integrity of the state government was at stake, so the commitment might have to be anchored in a preamble to the coalition agreement (infranken.de, 2023). And so it turned out. Compared to the preamble of the coalition agreement after the 2018 Bavarian elections, the new “Bavarian coalition” is committed to the “principles of our democracy” and to “protecting the liberal and democratic constitutional order” in the face of new social challenges. The joint government alliance therefore “resolutely opposes all forms of anti-Semitism, intolerance, xenophobia and racism” (Coalition Agreement, 2023).

Following their significant increase in votes, the Free Voters received a fourth ministry, taking over the Ministry of Digital Affairs from the CSU. The further division of ministries between the two parties remained unchanged – albeit with some shifts in responsibilities. The Green Party’s top candidate Katharina Schulze claimed that the ministries had be reallocated in line with personal interests. With regard to the decision that hunting now belongs to the Ministry of Economic Affairs, she remarked that this was “political cabaret” and asked “what does hunting law have to do with industrial strategy and the preservation of our prosperity?” (Jerabek et al., 2023). Overall, the new balance of power between the two parties was reflected by the outcome of the coalition negotiations. While Hubert Aiwanger and the Free Voters were given another ministry and some new responsibilities, however, at 0.16 percent of the state budget, the Ministry of Digital Affairs is relatively insignificant and the Free Voters also lost some of their past competences in the process. For example, the issues of tourism and gastronomy were transferred from Aiwanger’s Ministry of Economic Affairs to the CSU-led Ministry of Agriculture. The Free Voters also failed with their plan to remove the construction of the third runway at Munich Airport from the agenda or to lower the voting age in local elections to 16 (Jerabek and Kirschner, 2023). The balance of power in the new cabinet has not changed compared to the last legislative period: Just as in the Söder II cabinet (2018-2023), the executive in the Söder III cabinet (2023-2028) consists of 12 CSU and 5 Free Voter government members, despite the Orange Party gaining significant strength in the Bavarian state parliament in the 2023 Bavarian elections with ten more seats (see “the data”).

Conclusion 1

Already in the 2018 Bavarian elections, the CSU had its worst result in 73 years with 37.2 percent. In 2023, the CSU (again led by Prime Minister Markus Söder) slightly undercut this result. The last two elections in the region thus show that the party system of Bavaria, just as the German party system as a whole, is becoming more diverse in the wake of socio-economic, cultural and ecological changes (Walter-Rogg and Heinrich, 2023: 5). Although the state parliament is less colourful than in 2018 due to the Liberals not obtaining representation, there were more significant shifts between the parties in 2023. The shifts primarily favored the Free Voters and the AfD, both of which made further significant gains compared to the previous election five years earlier. The federal “traffic light” parties were clear losers of the 2023 Bavarian elections, especially the FDP. The Green Party, who was one of the winners of the 2018 state election and had hoped to continue on a series of good electoral performances after its gains in the 2021 federal election, also lost ground. The SPD had already lost many votes in the 2018 Bavarian election after a failed election campaign with a weak lead candidate (-10.9 pp) and fell to its lowest level in any Western German state in 2023, despite holding the office of chancellor at the federal level.

In view of the level of support for the Free Voters, there is growing concern among the Christian Social Union that the new electoral law will prevent them from entering the Bundestag. Under the new law, the CSU must receive enough second votes to surpass the 5% threshold nationwide. In the 2021 federal election, the CSU only just achieved this target with 5.2 percent. Such a result is at risk if the Free Voters run in the 2025 federal election and perform as well as they did in the 2023 Bavarian election. Even before the election, Hubert Aiwanger could envisage moving to Berlin if his party were to succeed in entering the Bundestag nationwide in 2025 (Berliner Zeitung 2023). Until now, the CSU could rely on campaigning with the leader of the Berlin CSU members of parliament and winning as many Bavarian direct seats as possible. This will only be possible if the new election law passed by the “traffic light” coalition is repealed by the Federal Constitutional Court. According to Matthias Moehl, a computer scientist and operator of the election analysis portal “Election.de”, it is “quite conceivable that the Free Voters could win 7.5 percent of the vote in Bavaria in the Bundestag elections, causing the CSU to slip below the five percent threshold” (Delhaes, 2023). In this case, it may be necessary for Markus Söder to run as his party’s top candidate in the next federal election and/or for the CSU in Bavaria to run a German-wide election campaign in order to mobilize as many supporters as possible.

The data

References

Albrecht, F. & Walter-Rogg, M. (2023). Der Einfluss bundespolitischer Themen auf den Landtagswahlkampf in Bayern 2018 – Eine Untersuchung der Twitter-Kommunikation von Bundes- und Landespolitikern. In M. Walter-Rogg & T. Heinrich (eds.), Die Landtagswahl 2018 in Bayern – Analysen zum Wahlverhalten und zur politischen Kultur im Freistaat. Springer VS, pp. 417-452.

Bayerisches Landesamt für Statistik (2023). Landtagswahl 2023. Online.

Berliner Zeitung (2023, 20 September). Freie Wähler in den Bundestag: Aiwanger kann sich Wechsel nach Berlin vorstellen. Berliner Zeitung.

Brunner, K. & Menner, S. (2023). Datenanalyse zur Landtagswahl: Niederbayern wählt anders. BR.

Bukow, S. (2018). Landtagswahl Bayern 14.10.2018. Ergebnisse und Analysen. böll.brief Demokratie & Gesellschaft 8, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung e.V.

Delhaes, D. (2023, 9 October). Wahl in Bayern. Die neuen Sorgen von CSU-Chef Markus Söder. Handelsblatt.

Forschungsgruppe Wahlen (2023). Landtagswahl in Bayern – Votum für Kontinuität – Freie Wähler und AfD stark, Kurzanalyse am 9.10.2023. ZDF.

Forschungsgruppe Wahlen (2023a). Zufriedenheit mit Regierung und Koalitionspartnern seit 01/2022. Online.

Forschungsgruppe Wahlen (2023b). Wahlanalyse Bayern 2023 – Votum für Kontinuität – Freie Wähler und AfD stark. Online.

Heim, M. (2023, 7 October). Wer könnte in Bayern regieren? Tagesschau.

Hummel, M. (2023). Bayern hat gewählt. München: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Bayern.

Infranken.de (2023, 10 October). Neuauflage der Koalition? Söder fordert klares Demokratie-Bekenntnis. Infranken.de.

Infratest dimap (2018). Wahlreport Landtagswahl Bayern 2018. Eine Analyse der Wahl vom 14. Oktober 2018. Online.

Infratest dimap (2023). BayernTREND September II. Repräsentative Studie im Auftrag der ARD. Online.

Jerabek, P., Kirschner, R., & Wendler, A. (2023, 8 November). Neues Kabinett steht – Söder: Kontinuität und Erneuerung. BR.

Jerabek, P. & Kirschner, R. (2023). CSU und FW zum Zweiten: Wer ist der Hund und wer der Schwanz? BR.

Kahrs, H. (2018). Die Wahl zum 18. Bayerischen Landtag am 14. Oktober 2018. Wahlnachtbericht und erster Kommentar. Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung.

Koalitionsvertrag (Coalition agreement) (2023). Freiheit und Stabilität. Für ein modernes, weltoffenes und heimatverbundenes Bayern. Koalitionsvertrag für die Legislaturperiode 2023-2028.

Rappsilber, F. (2023, 3 May). Kritik an Grünen:Söder: Lehnen “Umerziehungswünsche” ab. ZDF.

Schmid, A. (2023, 8 October). Schlechtestes SPD-Ergebnis mit Faeser und AfD-Rekord: Das sind die Gründe. Frankfurter Rundschau.

Schwesinger, H. (2023, 9 October). Analyse. Warum die CSU nicht vom Unmut profitieren kann. Tagesschau.

Tagesschau (2023). Wahlen – Länderparlamente – Bayern – 2023 – Wie die Wähler wanderten vom 18.10.2023. Tagesschau.

Thurner, P. W., Küchenhoff, H., Walter-Rogg, M., Heinrich, T., Klima, A., Knieper, T., Haupt, H., Mauerer, I., Mang, S., & Schnurbus, J. (2023). Die Universitätsstudie Bayernwahl 2018 (USBW18): Design und ermittelte Wählerwanderungen. In M. Walter-Rogg & T. Heinrich (eds.), Die Landtagswahl 2018 in Bayern – Analysen zum Wahlverhalten und zur politischen Kultur im Freistaat. Springer VS, pp. 21-63.

Walter-Rogg, M. & Heinrich, T. (2023). Eine neue, buntere Politik in Bayern? M. Walter-Rogg und T. Heinrich (eds.), Die Landtagswahl 2018 in Bayern – Analysen zum Wahlverhalten und zur politischen Kultur im Freistaat. Springer VS, pp. 3-19.

Zeit Online (2023, 30 October). Bayerns FDP bietet sich Söder als Koalitionspartner an. Zeit.

Zicht, W. & Cantow, M. (2023). Landtagswahl 2023 in Bayern. Wahlrecht.de.

Notes

citer l'article

Melanie Walter-Rogg, Regional election in Bavaria, 8 October 2023, Jun 2024,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue