Regional election in Berlin, 12 February 2023

Felix Wortmann Callejón

Graduate student at the London School of Economics and Political ScienceIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Felix Wortmann Callejón

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

Introduction

On November 16th 2022, the Berlin State Constitutional Court (BCC) ruled that the results of both the state and local elections in Germany’s capital of Berlin, that took place on the 26th of September 2021 together with the federal election, were invalid and had to be repeated within 90 days. 1 Thus 88 days after the ruling, Berliners went to the polls to elect their state parliament – the Abgeordnetenhaus – for a second time in less than 17 months. While Berlin does not have the economic might of North-Rhine Westphalia, Baden-Württemberg, or Bavaria, the Berlin elections were nevertheless an important test for the national government, as much of the traffic light coalition’s support is concentrated in urban areas. The performance of the SPD (Social Democratic Party of Germany, S&D), the Greens (Alliance 90/The Greens, Greens/EFA), and the FDP (Free Democratic Party, RE) was thus under close scrutiny. As the first state election in eastern Germany after the 2021 federal elections, Berlin was also important to the Left (The Left, GUE/NGL), which has been part of several state governments with steady election results since the early 2000s, but is only present in the current German Parliament due to winning two constituencies in East Berlin. Finally, the election presented an opportunity for the CDU (Christian Democratic Union, EPP) to shore up a veto-proof majority in Germany’s upper house, the Bundesrat.

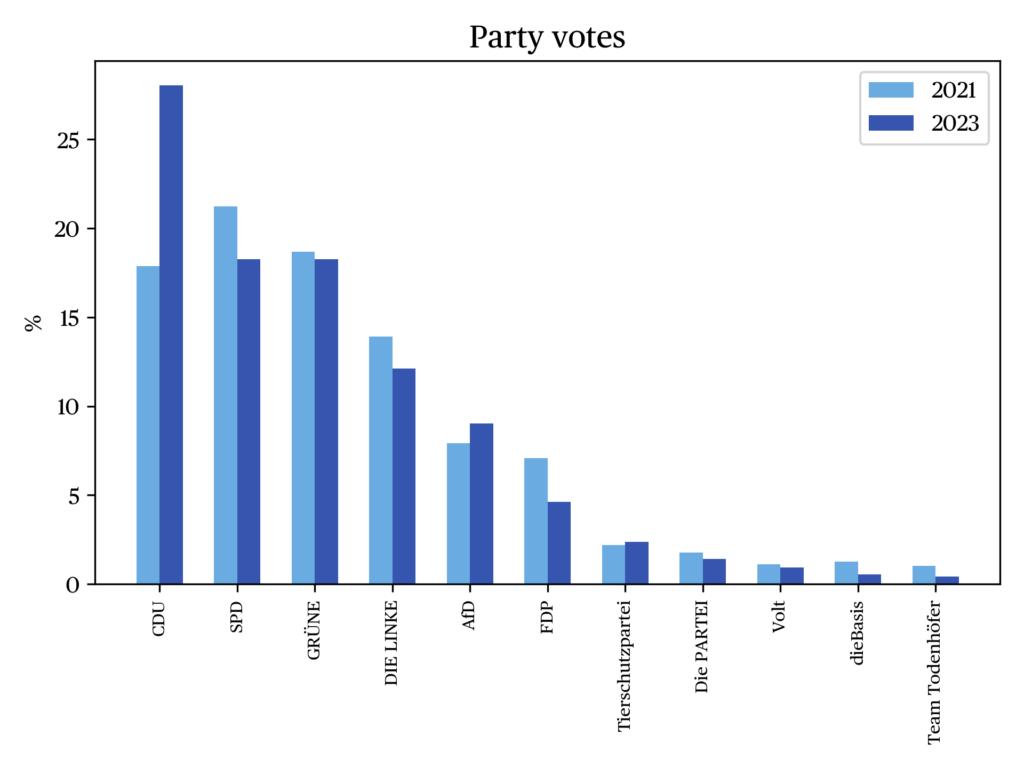

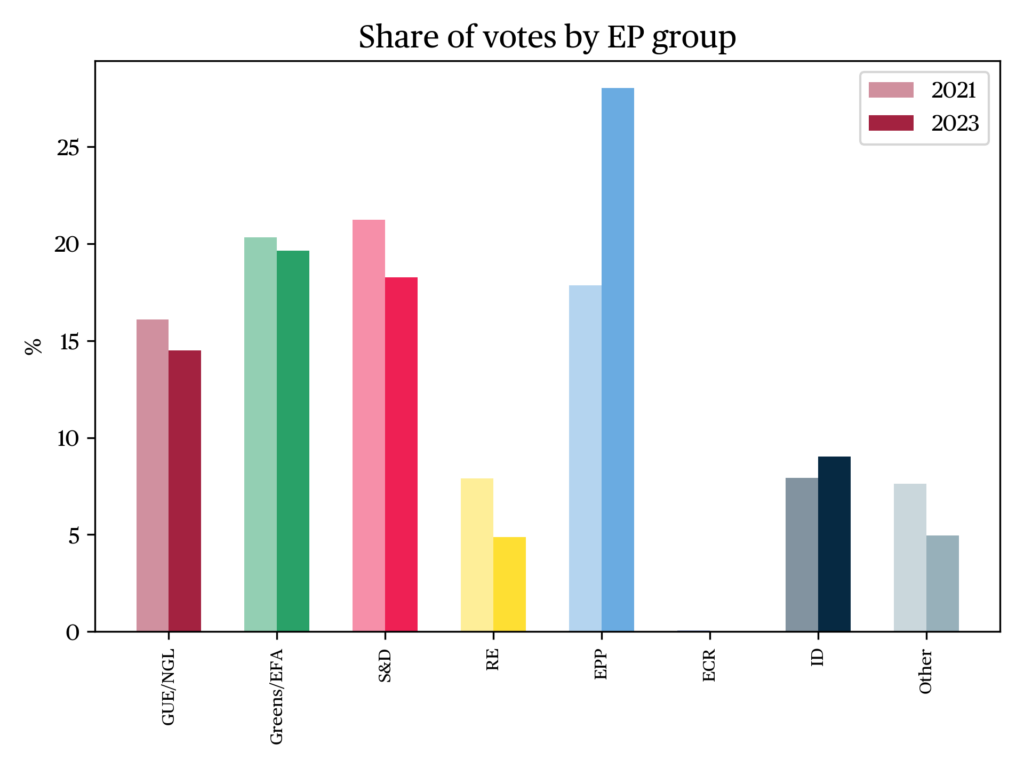

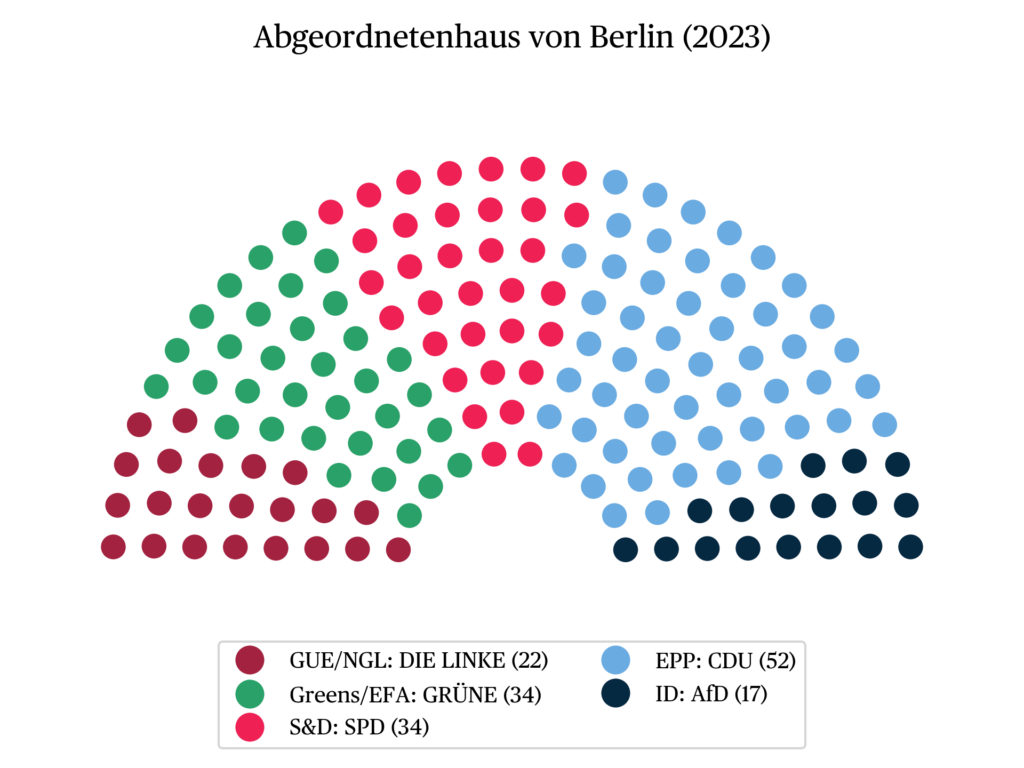

The results of the 2023 election differed tremendously from those in 2021 (see “the data”). While the governing parties on both state and federal levels all lost votes, the CDU and the AfD (Alternative for Germany, ID) gained votes. The new state government, which is formed by a coalition of the CDU and the SPD, will have three years to impact Germany’s biggest city. The following review will address the context of the election of 2021 and the BCC’s reasoning for annulling the results, as well as the results of the election that tipped the scales from a centre-left to a centre-right coalition.

Context

In September of 2021, Berlin voters participated the closing act of a long electoral year, in which five German state parliaments, as well as the federal parliament – the Bundestag – were elected. Berliners were able to participate in elections on the federal, state, and local level, as well as in a referendum on expropriating real-estate companies (cf. Sullivan 2021). Overall, this meant there were up to six choices to be made by each voter. The complexity of this decision, along with COVID safety precautions and the Berlin Marathon, that took place on the same day, led to disruptions in the voting process all over the city (cf. Rockmann 2023; Waldhoff 2021). Errors and subsequent complaints were plenty, but most notably, 37% of polling stations closed after 18:00, but before 18:30, and 11% of the polling stations closed even later. Additionally, “5% of the polling stations had to temporarily interrupt the voting procedure during [election day] due to missing ballots” (Rockmann 2023: 10). In the aftermath of the election, the Berlin Electoral Commissioner was asked to be relieved of her duties and complaints were filed to the Bundestag’s election scrutiny committee and the BCC (Rockmann 2023: 3ff).

Thirteen and a half months after the 2021 election, the BCC invalidated the results of the state and local elections, arguing that the gravity of the errors could have changed the result of the election and the constitutional principles of generality, equality, and freedom of the vote had been thus violated. The election had to be repeated within 90 days of the November 16th ruling (cf. Jani 2022). 2

The earliest polls for the February 2023 election showed that the election would again see a three-way race between the SPD, the Greens, and the CDU. In a poll conducted by infratest dimap (2022) immediately after the BCC’s November ruling, support for each of the three parties was within each of the two other parties confidence intervals. Yet, by January the CDU started to pull ahead of the SPD and the Greens (infratest dimap 2023b) and had clearly overtaken both of its rivals two weeks before the election (infratest dimap 2023a).

As the 2023 election was a repetition of the annulled 2021 election, many of the topics that were relevant to Berliners back then continued to be relevant for the 2023 election. Housing and mobility were the most important topics for voters (infratest dimap 2023b; Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2023), while the topics of immigration, as well as crime and security, gained importance through attacks on the police and firefighters on New Years Eve (DER SPIEGEL 2023), which were politicised by the CDU. This environment favoured the SPD and CDU, who were perceived as competent in the areas of housing and security, respectively (Forschungsgruppe Wahlen 2023). Surprisingly, and although different parties were to profit from the repetition of the election in varying degrees, the repetition of the election itself was not a polarising issue. 63% of voters supported the decision to completely repeat the elections, and only a majority of SPD voters favoured a partial or no repetition of the election, while a majority of supporters of all other parties supported the complete repetition (infratest dimap 2022). 3

In terms of political personnel, the leading candidates of the SPD – mayor of Berlin Franziska Giffey – and the CDU – former member of the Bundestag and Abgeordnetenhaus opposition leader Kai Wegner – were clearly preferred by the electorate. The Green leading candidate, Bettina Jarrasch, was already relatively unpopular in 2021. She was unable to increase her approval rating from the 16% of voters that approved of her at the time of the 2021 election (infratest dimap 2023a). Franziska Giffey’s popularity, however, fell by six points with respect to the 44% of voters that approved of her work shortly before the 2021 election, while Kai Wegner was able to increase his popularity by the same amount that Giffey lost (infratest dimap 2023a). Considering the shift in momentum in favour of the CDU and their leading candidate Wegner, and with overall satisfaction with the work of the state government at 30% (infratest dimap 2023a), the eventual election result was not surprising.

Election results

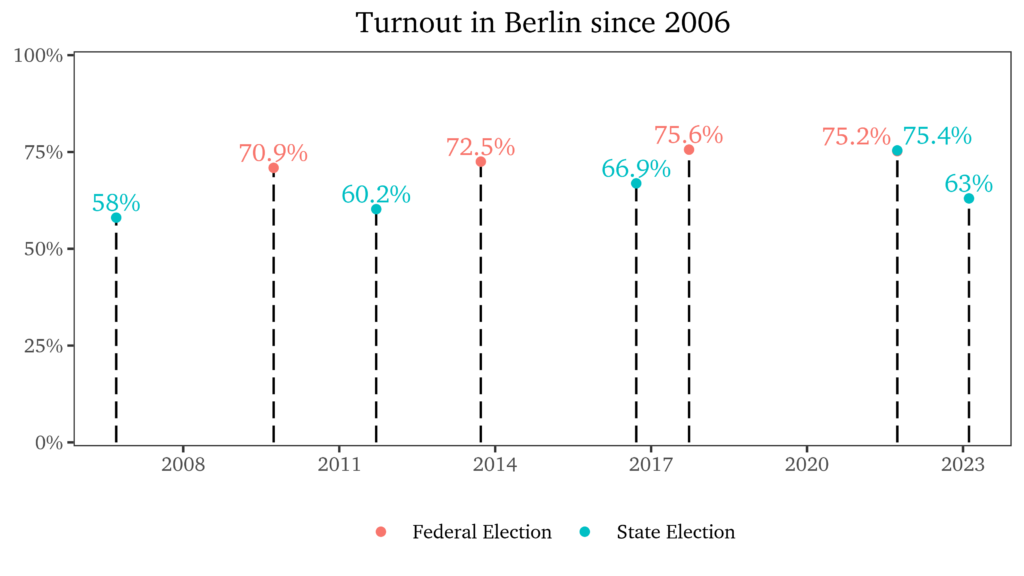

On election day, 63% of eligible voters turned out to vote, which, for an off-cycle election after a short campaign in the winter, was a high level of electoral participation (see Figure a; cf. Damsbo-Svendsen and Hansen 2023). Electorally, the CDU gained 10.2 percentage points, leading all other parties with 28.2% of the list votes as well as 29.7% of district votes and thus 61.5% of all direct mandates. The SPD won 18.4% of the list votes, loosing 3 percentage points with respect to 2021. Moreover, the Social Democrats lost 21 of the direct mandates they had won in 2021. The Greens did slightly worse than in 2021 and with 18.4% of the list votes finished just 53 votes behind the SPD. The Left lost 1.9 percentage points with respect to their 2021 list votes and with 12.2% of the votes spared itself from an electoral disaster; the Left’s candidate Klaus Lederer expressed relief about the result on election night (tagesschau.de 2023a). The AfD was the only other party to gain votes (relatively). It had led the judicial effort to overturn the election (cf. Rockmann 2023) and – like the CDU – campaigned in favour of automobiles in transport policy and was thus able motivate turnout (dpa 2022). The big looser of the night was the FDP that only

received 4.6% of the list votes and hence failed to re-enter parliament.

Overall, the election result is explained well by both second-order election (cf. Reif, Schmitt and Norris 1997) and mid-term loss (cf. Tufte 1975) theories. On the one hand, the result mirrors a spillover of popularity of the parties on the national level (i.e. as predicted by second-order theory). In POLITICO’s Poll of Polls at the time of the 2023 Berlin election, out of the parties in federal Government, only the Greens had (marginally) higher approval ratings than at the 2021 election, while SPD and FDP declined in the public opinion (POLITICO 2023). Meanwhile, the CDU lead all parties in opinion polling with about 28% of the hypothetical vote and the AfD, too, was 5 percentage points ahead of its 2021 result (POLITICO 2023). The changes in polling support are proportional to the changes in vote shares from 2021 to 2023 in Berlin. On the other hand, this was a rather surprising election, roughly one year into the five-year term that the coalition was expecting to have. The strategic incentives in the year ahead of an election are after all very different from the incentives of a first year in office and the opposition gaining support in

the middle of an electoral cycle is one of the best documented patterns in political science (cf. Campbell 1985).

4

It is thus not surprising to see Government parties being punished.

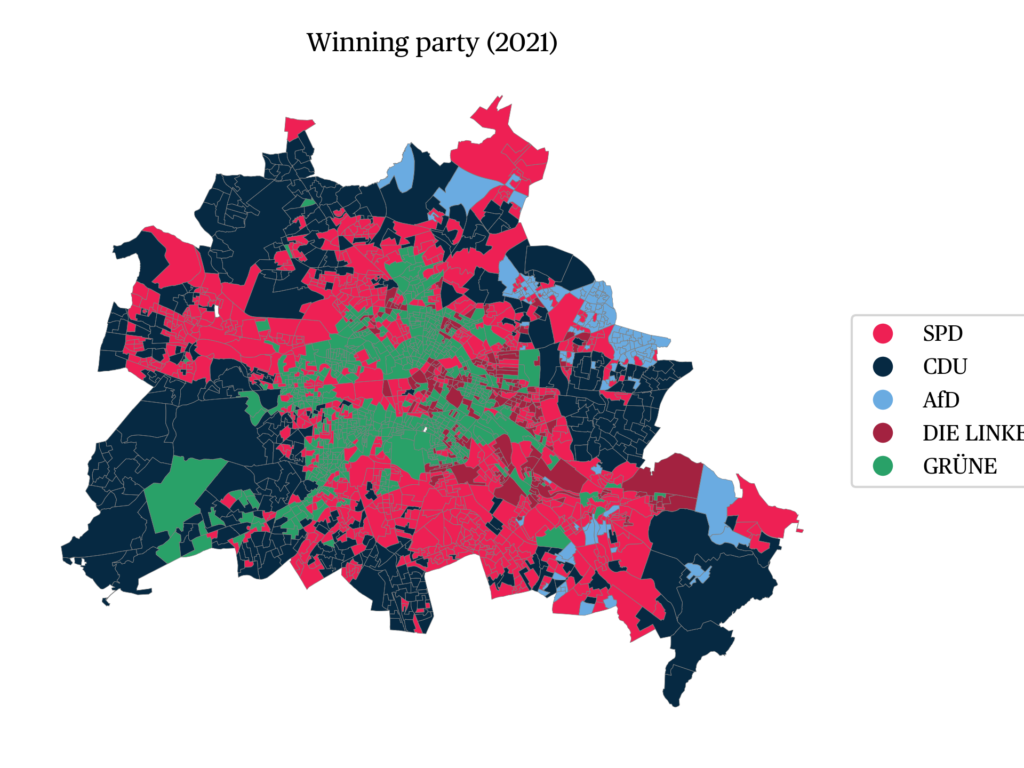

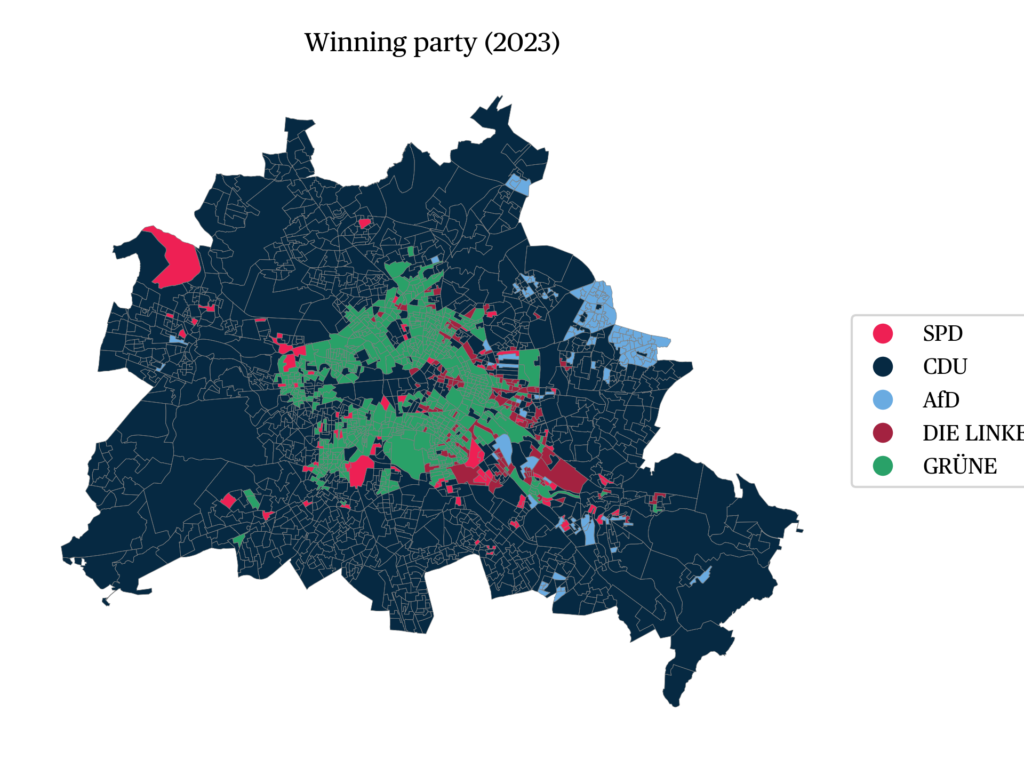

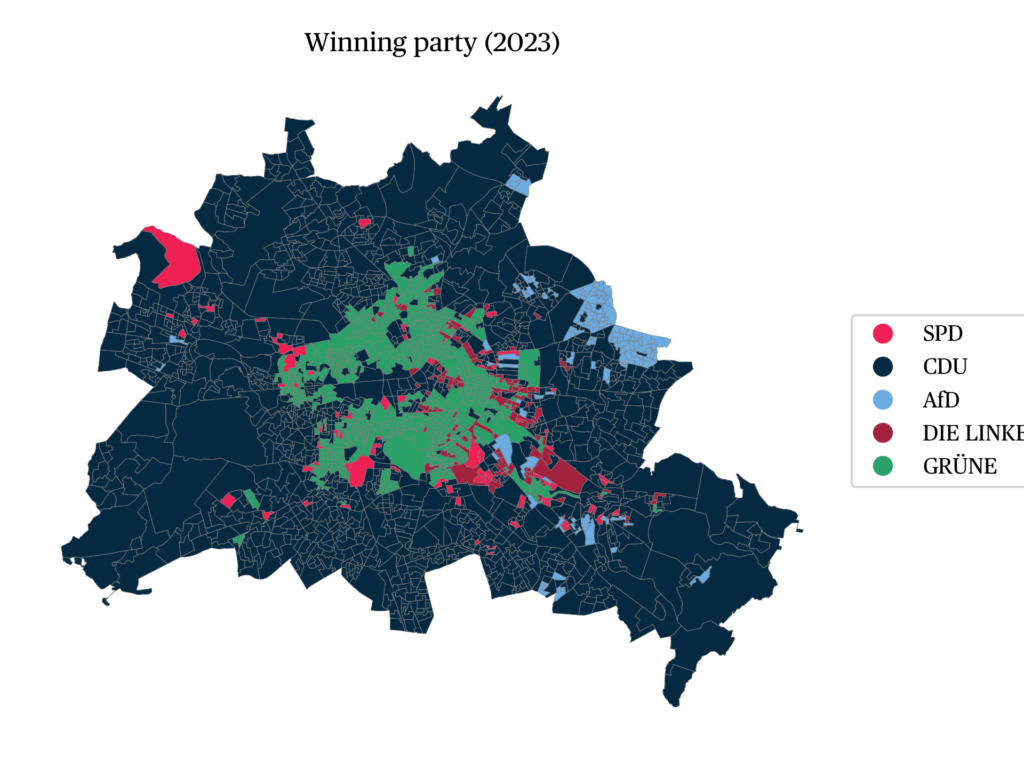

Geographic Trends

Looking at party support in the voting precincts (see Figure b2), a clear pattern emerges. Voters in the city centre backed Green and Left candidates, while voters in the periphery supported SPD and CDU candidates. This narrative of a conflict between city-centre urbanites and suburban voters was heavily recited in the media (cf. Hönicke, Kneist and Slawinski 2023). However, the choropleth maps (see Figure b) that were presented in this context are deceiving, as they hide the underlying heterogeneity in the vote shares in each precinct.

and 2023

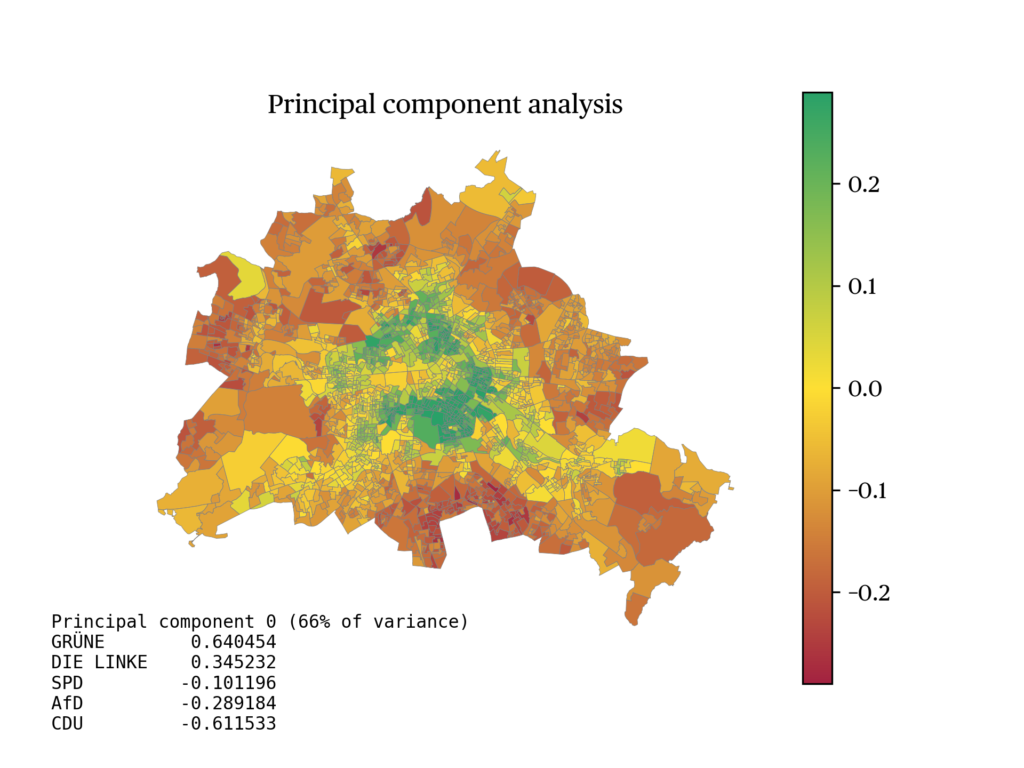

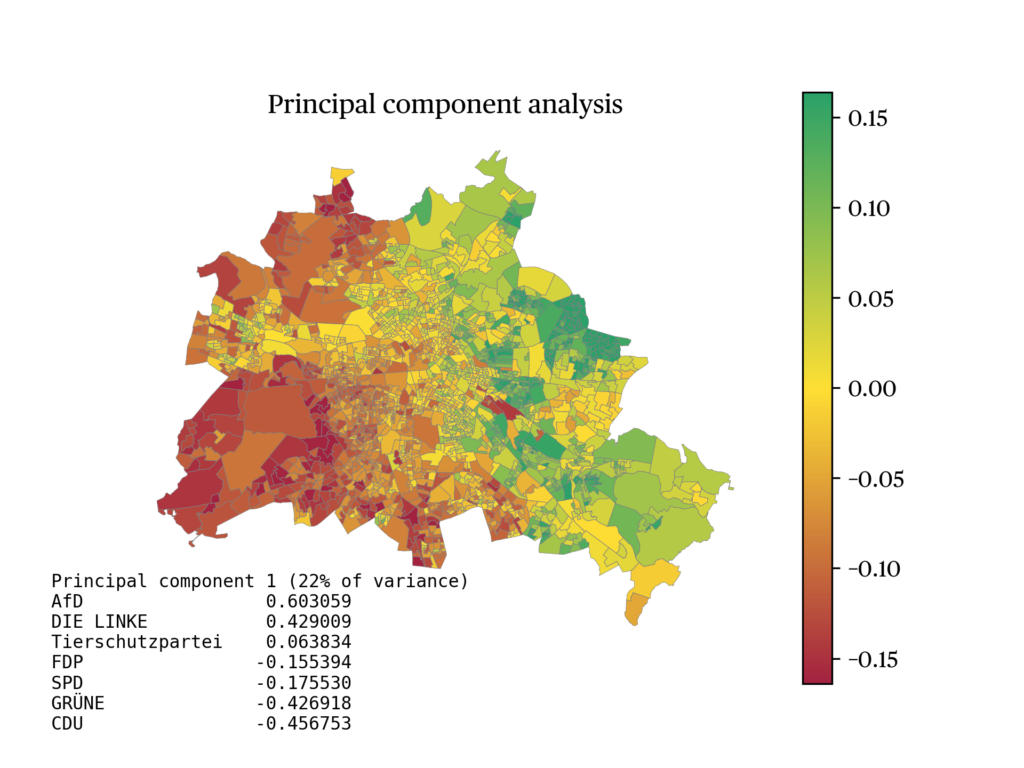

A principal component analysis on the vote shares in each of the voting precincts also detects the urban-suburban conflict (see Figure c1). The first principal component, that loads positively on the vote shares of the Greens and the Left explains two thirds in the variance of the vote shares and produces a familiar geographical picture. This pattern was however not new for 2023. In 2021 (cf. Hublet 2022), a very similar principal component explained the same amount of electoral variation. This suggests that the underlying

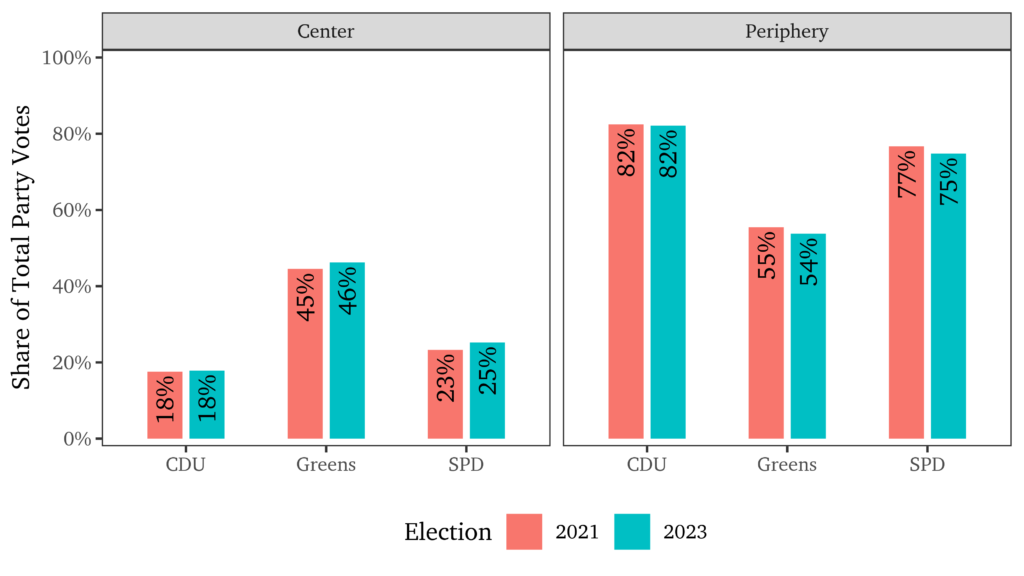

conflicts between the centre and periphery did not change (much) from 2021. Figure d provides further evidence to the stability of the center vs. periphery conflict.

The CDU received around 82% of its total votes from the periphery in both elections.

5

Relative vote shares of the Greens and the SPD were also stable across elections. Changes in the election results were thus proportional to the vote shares in 2021, as opposed to the asymmetric mobilisation that was described by news outlets. It is likely, that the visual change in the choropleth map stems from voters switching from the SPD, which in 2021 experienced a boost from the electoral success on the federal level, to voting for the CDU. This change is however only visible in the periphery, where margins between CDU and

SPD were already tight in 2021.

6

Interestingly, the second electoral cleavage, a distinction between East and West Berlin, was largely overlooked by the media. The second principal component, which loads positively on the vote shares of AfD, the Left and the Tierschutzpartei (animal protectionparty) and negatively on the vote shares of the CDU, the SPD, the Greens, and the FDP,reveals a clear distinction between the territories of the former GDR and FRG. This indi-cates that patterns of difference between East and West German voters do not only persiston the federal level (cf. Höhne, 2021), but also in Berlin. This is important particularly to the AfD, which, as a populist radical right party (cf. Arzheimer and Berning, 2019), aims to represent “the true people”, but currently seems relatively unappealing to votersin West Berlin. Even though the AfD gained votes in every electoral district, the gains were very modest in the West (largely between 0% and 1% of the vote share) and more pronounced in the East (Breher, Tröbs and Wittlich 2023). For the Left, East Berlin is crucial for the party’s survival. The Left failed to clear the 5% hurdle to gain representation in parliament in the 2021 federal election, but is still represented in the Bundestag due to a clause in the German electoral law which allows parties to be represented with their complete number of list votes, if they manage to win three direct mandates in the single-member districts (Faas and Klingelhöfer 2022). Two of the three single-member districts that the Left was able to win are located in East Berlin. Crucially, under the new electoral law which was passed in March of 2023 (cf. Deutscher Bundestag 2023) the Left would only send it’s three direct candidates to the federal parliament. The party thus has to ask itself, how it can retain it’s electoral appeal in the East, while expanding its popularity in the West.

Government and Coalition Formation

The outcome of the election was furthermore very interesting for the process of government formation. The existing coalition of the SPD, the Greens, and the Left technically still possessed a narrowed majority of seats and thus could have continued its business as before the election. Crucially, since the SPD had only received 0.02% more votes than the Greens, it would have been difficult for the SPD to claim the leadership of the coalition and Giffey’s bid for mayor would have certainly been challenged by Jarrasch. Other than continuing the existing coalition, the CDU had two distinct opportunities to govern: either with the SPD in a so called “grand coalition” or with the Greens. This latter option seemed the least likely, as the CDU and the Greens had been explicitly critical of each other in the run up to the election (Kunze 2023). This left the SPD as king maker: either it would renew its coalition with the Greens and the Left, ceding some power to the Greens but likely keeping control of the town hall, or make Kai Wegner the first Conservative mayor of Berlin since Eberhard Diepgen (CDU) was voted out of office in June of 2001, but remain in a position of greater leverage over the politics of the city.

After preliminary talks in all three coalition constellations (Knobbe et al. 2023), the CDU and the SPD announced that they would enter formal coalition negotiations (dpa 2023). On April 4th, the CDU and the SPD presented the results of their bargaining in the form of a 135 page coalition agreement. The agreement focuses on the topics of mobility and housing, but also on modernising the cities bureaucracy (cf. rbb24 2023). Members of the SPD had until the 24th of April to approve or reject the agreement and a party convention of the CDU similarly had to approve the agreement. While the latter was merely a formality, the result of the SPD membership was projected to be close. As with the “grand coalition” agreement on the federal level in 2017, the youth organisation of the SPD was the most vocal critic from within the party, recommending that its members vote against the agreement (see nogroko.berlin). Nevertheless, the party headquarters announced on April 23rd that 54.3% of the 11,886 party members which had participated, voted in favour of the coalition (Thewalt 2023).

With Franziska Giffey now moving into her new role as Senator for the economy, business, and energy (Betschka 2023), Kai Wegner was ready to take over as mayor. After two failed votes with both the CDU and SPD blaming each other for falling out of line (Wehner 2023), Kai Wegner was finally elected in the third round with 86 votes – as many as the coalition held seats in parliament. An announcement of the AfD, stating that they had also voted for Wegner marred his mayorship from the first day (Wehner 2023).

The change of the state government also has wider implications for the national government. Through governing in Berlin, the CDU was able to add four seats to its majority in the Bundesrat, Germany’s upper house. This means that even if the CDU looses control of the government in Hesse later in 2023, it will retain control of the upper house and is thus able to block some proposals of the federal government through the second chamber.

Conclusion

The 2023 Berlin election represent a unique event in the modern political history of Germany, notably due to the cancellation and subsequent repeating of the previous year’s election. The results show a slight shift in political preferences, with a significant share of voters moving from the centre-left SPD to the centre-right CDU. As expected, the result of the election reflects national political trends and the enduring conflict between the urban centre and suburban periphery of Germany’s heterogenous capital. As a bell-weather for urban voters, the consequences of this election extend beyond Berlin’s borders, sending a signal to the federal government. The emerging “grand coalition” of the CDU and the SPD will undeniably influence the city’s future, but early quarrels indicate that the implications of the election will continue to unfold.

The Data

References

Arzheimer, K. & Berning, C.C. (2019). How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and their voters veered to the radical right, 2013–2017. Electoral Studies 60.

Besley, T. & Case, A. (1995). Does Electoral Accountability Affect Economic Policy Choices? Evidence from Gubernatorial Term Limits. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 110(3), 769–798.

Besley, T. & Burgess, R. (2002). The Political Economy of Government Responsiveness: Theory and Evidence from India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(4), 1415–1451.

Betschka, J. (2023). Das ist der neue Berliner Senat: Designierte Senatoren und Staatssekretäre im Überblick. Der Tagesspiegel Online.

Breher, N., Tröbs, L., & Wittlich, H. (2023). Geografische Wahlanalyse: Wo SPD, Grüne und Linke am meisten verloren haben. Tagesspiegel.

Campbell, J. E. (1985). Explaining Presidential Losses in Midterm Congressional Elections. The Journal of Politics 47(4), 1140–1157.

Damsbo-Svendsen, S. & Hansen, K. M. (2023). When the election rains out and how bad weather excludes marginal voters from turning out. Electoral Studies 81.

DER SPIEGEL (2023). Silvester in Berlin: Polizei hat bislang 44 Verdächtige identifiziert. Der Spiegel.

Deutscher Bundestag (2023). Wahlrechtsreform zur Verkleinerung des Bundestages beschlossen. Online.

dpa (2022). Berliner Abgeordnetenhaus: AfD will bei Wiederholungswahl in Berlin stärker werden. Die Zeit.

dpa (2023). Berlin: CDU und SPD haben ihre Chefverhandler festgelegt. Der Spiegel.

Faas, T. & Klingelhöfer, T. (2022). German politics at the traffic light: new beginnings in the election of 2021. West European Politics 45(7), 1506–1521.

Forschungsgruppe Wahlen (2023). Kurzanalyse zur Wiederholungswahl zum Berliner Abgeordnetenhaus. Technical report Forschungsgruppe Wahlen e.V. Mannheim.

Hublet, F. (2022). Regional election in Berlin, 26 September 2021. Electoral Bulletins of the European Union 2.

Höhne, B. (2021). Konvergenz oder Divergenz? Einstellungen von Parteimitgliedern und Partizipation bei Bundestagswahlen im Ost-West-Vergleich. Recht und Politik Beiheft 2021(8), 73–91.

Hönicke, C., Kneist, S., & Slawinski, M. (2023). Innen grün, außen schwarz: Diese Berliner Bezirke driften politisch auseinander. Der Tagesspiegel.

infratest dimap (2022). BerlinTREND November 2022. Technical report, infratest dimap Berlin. Online.

infratest dimap (2023a). BerlinTREND Februar 2023. Technical report, infratest dimap Berlin. Online.

infratest dimap (2023b). BerlinTREND Januar 2023. Technical report, infratest dimap Berlin. Online.

Jani, L. (2022). Verfassungsgerichtshof des Landes Berlin erklärt die Wahlen zum Berliner Abgeordnetenhaus und den Bezirksverordnetenversammlungen vom 26. September 2021 für ungültig. Online.

Klöpper, A. (2022). Wahlwiederholung in Berlin: Die ungerechte Neuwahl. taz.

Knobbe, M., Lehmann, T., Medick, V., Reiber, Schaible, J., & Teevs, C. (2023). Sondierungen in Berlin: Giffeys Wendemanöver. Der Spiegel.

Kunze, R. (2023). Berlin-Wahl: CDU-Chef schließt Zusammenarbeit mit Grünen aus. rbb24.

POLITICO (2023). POLITICO Poll of Polls — German polls, trends and election news for Germany. Online.

rbb24 (2023). Berliner CDU und SPD setzen Schwerpunkte bei Mobilität, Bauen und Verwaltung. rbb.

Reif, K., Schmitt, H., & Norris, P. (1997). Second-order elections. European Journal of Political Research 31(1-2), 109–124.

Rockmann, U. (2023). German, Berlin and Regional Elections 2021 in Berlin: What happened? What is known and what is unknown? SSOAR Pre-Print.

Sullivan, A. (2021). Berliners vote ’yes’ on property expropriation. Deutsche Welle.

tagesschau.de (2023a). tagesschau 20 Uhr. Online.

tagesschau.de (2023b). Wie Wähler bei der Wahl in Berlin wanderten. Online.

Thewalt, A. (2023). Knappe Mehrheit: 54,3 Prozent der Berliner SPD-Mitglieder stimmen für Koalition mit der CDU. Der Tagesspiegel Online.

Tufte, E. R. (1975). Determinants of the Outcomes of Midterm Congressional Elections. American Political Science Review 69(3), 812–826.

Waldhoff, C. (2021). Wahlen in Berlin: ein Bericht. Verfassungsblog.

Wehner, M. (2023). Kai Wegner in Berlin gewählt: Opposition spricht von Koalition des Chaos. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

Notes

- I am indebted to an anonymous reviewer who provided careful feedback, as well as to Julius Kölzer, who coded voting precincts as in- or outside the circle line and was willing to share his work with me. Julius also served as an inspiring conversation partner in the drafting of this manuscript.

- The decision to overturn the election in its entirety was made by a seven to two split decision of the nine judges. The repetition of the complete election – as opposed to the decision of the Bundestag to only repeat the election in 431 precincts – was questioned widely, e.g. by Klöpper 2022, but most prominently

by the former Berlin election commissioner, Ulrike Rockmann (2023). - Even 48% of SPD voters favoured a complete repetition.

- For a discussion of electoral incentives under different institutional constraints cf. Besley and Case (1995); Besley and Burgess (2002).

- Voting precincts were coded as “center” if they were located within Berlin’s circle line (“Ringbahn“). Circa a dozen precincts were dissected by the circle line. If the majority of an area of a precinct was located on the inside of the circle line, it was coded as being in the center and vice versa. The circle line is a common landmark to separate Berlin’s city center, which due to its roots as a collection of different towns and cities, and the division into East and West lacks a unique city center.

- Estimates of voter migration by infratest dimap (tagesschau.de 2023b) show that indeed the CDU gained most of its new voters from the SPD.

citer l'article

Felix Wortmann Callejón, Regional election in Berlin, 12 February 2023, Nov 2023,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue