Regional election in Brandenburg, 22 September 2024

Charlotte Kleine

Editor, BLUEIssue

Issue #5Auteurs

Charlotte Kleine

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

On September 22, 2024, the 8th Brandenburg State Parliament was elected. The election took place two weeks after the state elections in Saxony and Thuringia – also eastern German federal states. The poor election results of the three parties forming the federal government in these three elections contributed to the collapse of the ‘traffic light’ coalition at federal level.

Brandenburg is a rural and sparsely populated federal state that surrounds Berlin and borders Poland to the east. Major cities include the university and state capital Potsdam, as well as Cottbus and Frankfurt (Oder). The most important economic sectors in the state are automobile manufacturing – a controversial Tesla gigafactory has been operating in Grünheide since 2022 –, the steel industry, as well as energy and agriculture. While Brandenburg is considered one of the poorer federal states in absolute terms, its economy has developed positively in recent years, making it one of Germany’s most dynamic regions.

Electoral System

The Brandenburg State Parliament’s 88 members are elected every five years. Eligible voters have two votes: the first for a direct candidate in their district, and the second for a party or list. The second vote determines the proportional distribution of seats in parliament. To enter parliament, parties must either win over five percent of the second votes or at least one direct mandate.

The minimum voting age in municipal, European, and state elections in Brandenburg is 16. About two million people were eligible to vote in this election. Voter turnout reached a historic high of 72.9% in 2024 (+11.6pp compared to 2019), the highest turnout since the state’s founding in 1990.

Results

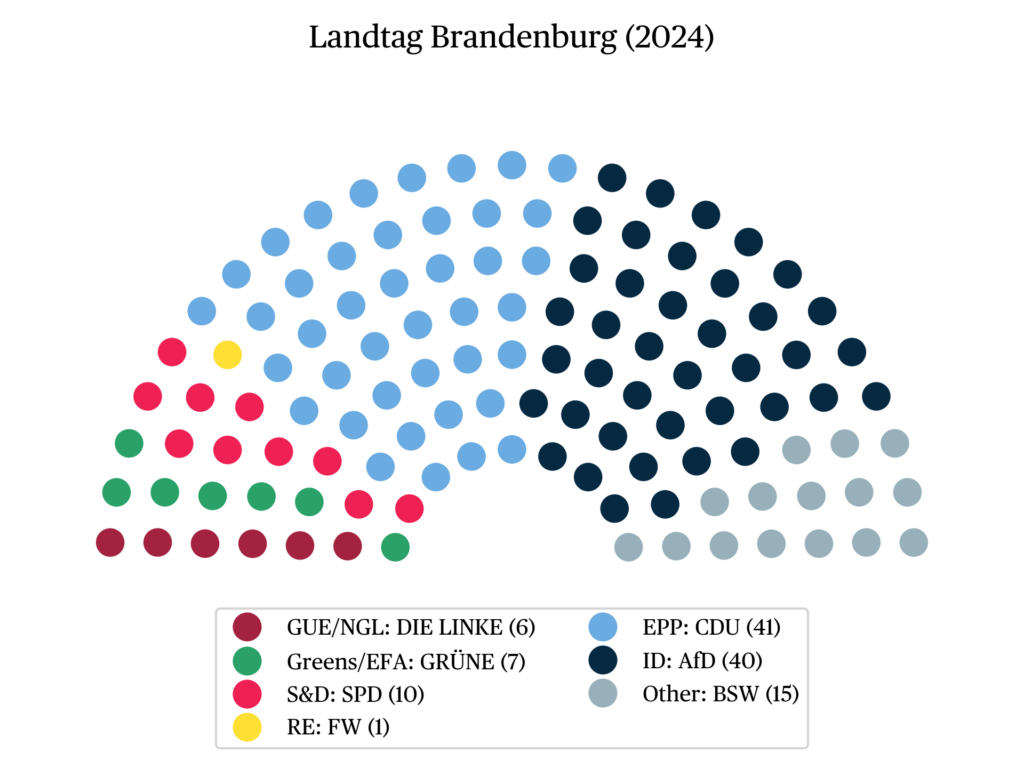

This state election significantly changed Brandenburg’s political landscape. Before the election, six parties were represented in the state parliament, but only four managed to re-enter or newly enter it.

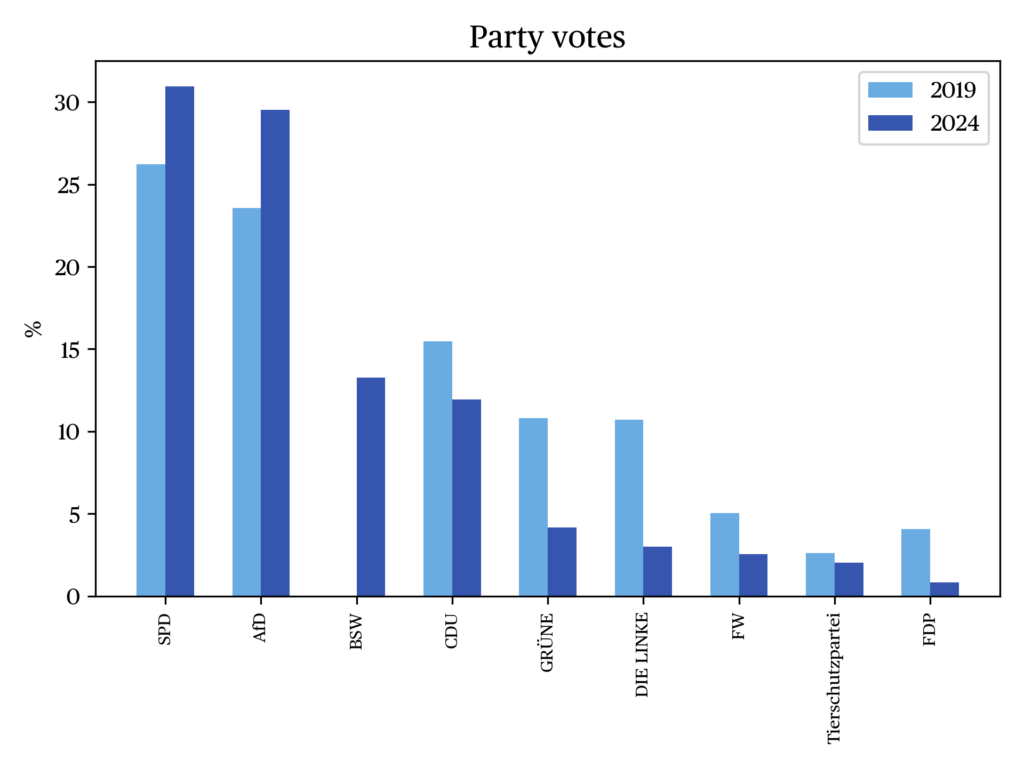

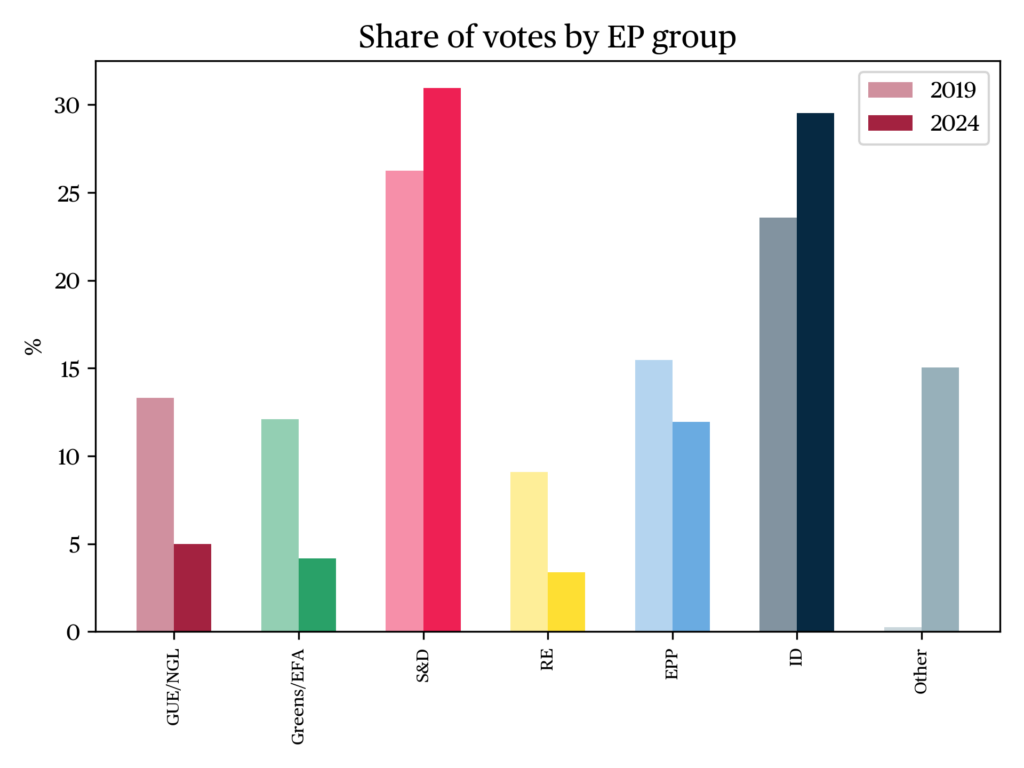

The Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD, S&D) has been governing Brandenburg uninterruptedly since 1990, even holding an absolute majority of seats from 1994 to 1999. With 30.8% of the second votes, the SPD again received the most votes and improved its 2019 result by 4.7 percentage points (pp). Nevertheless, this remains the SPD’s second-worst result in Brandenburg.

Leading up to the election, it didn’t appear that the SPD would win – polls sometimes saw the party below 20%, often behind the AfD. Still, within the incumbent coalition (SPD, CDU, and Greens), the SPD managed to maintain its position as the most stable force: 44% of respondents expressed satisfaction with its government performance – an approval rating much higher than the CDU’s (29%) and Greens’ (16%).

When asked who should lead the next government, 42% of respondents cited the SPD. While this figure did not give the party an absolute majority, it did give it a significant edge over its competitors. Furthermore, economic concerns and social justice were key motivators for many voters, two areas in which the SPD was considered more competent than its rivals. The SPD even improved slightly on social justice compared to the last election, widening its lead over the AfD and BSW.

The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) came in second with 29.23% (+5.7), securing 33 seats and thus achieving a blocking minority. This means that it can obstruct constitutional changes that require a two-thirds majority.

The newly formed Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), which split from Die Linke (The Left), came in third with 13.48%. The BSW’s federal platform focuses on opposing the shipment of arms to Ukraine and calling for diplomatic solutions to the war. Though foreign policy is outside state jurisdiction, these issues featured prominently in the campaign. The BSW also promotes restrictive migration policies and has been criticized for using nationalist rhetoric, though it portrays itself as the “voice of the sensible center.”

Among the election’s losers was the CDU (12.10%, -3.5). The Greens (4.13%, -6.7) lost their only direct mandate in Potsdam I and dropped below the 5% threshold, thus missing re-entry for the first time since 2009. Die Linke (3%, -7.7) also failed to enter parliament for the first time since 1990 – a historic low in an eastern state, largely due to the BSW’s emergence.

The BVB/Free Voters lost all seats with only 2.6% (-2.5), and the liberal FDP, though part of the federal government, garnered just 0.8% of the vote (down from 4.1% in 2019).

Key campaign issues

Despite varying priorities, the campaign was dominated by migration, internal security, the cost of living, and the Ukraine war.

The SPD emphasized traditional social democratic themes like social cohesion. The AfD, on the other hand, focused heavily on migration policy issues. In its official ‘government programme’, the party called for a ‘remigration pact’, which would involve the return of migrants to their countries of origin. The use of the term ‘remigration’ sparked mass protests against the AfD across Germany in February 2024 (Deutschlandfunk, 2024).

The CDU spoke out in favour of strengthening the skilled trades and SMEs to secure regional economic strength and proposed the establishment of a “Border Police” force modeled after a similar one in Bavaria.

The Greens focused on climate and educational policy, calling for solar and wind expansion and a coal phase-out by 2030. They also demanded better staff ratios in schools and childcare.

In an attempt to establish itself, the BSW demanded a new peace policy, educational reforms and increased funding for local authorities. Throughout the campaign, the BSW deliberately ignored the fact that foreign policy is not the responsibility of the federal states.

Who voted where and how?

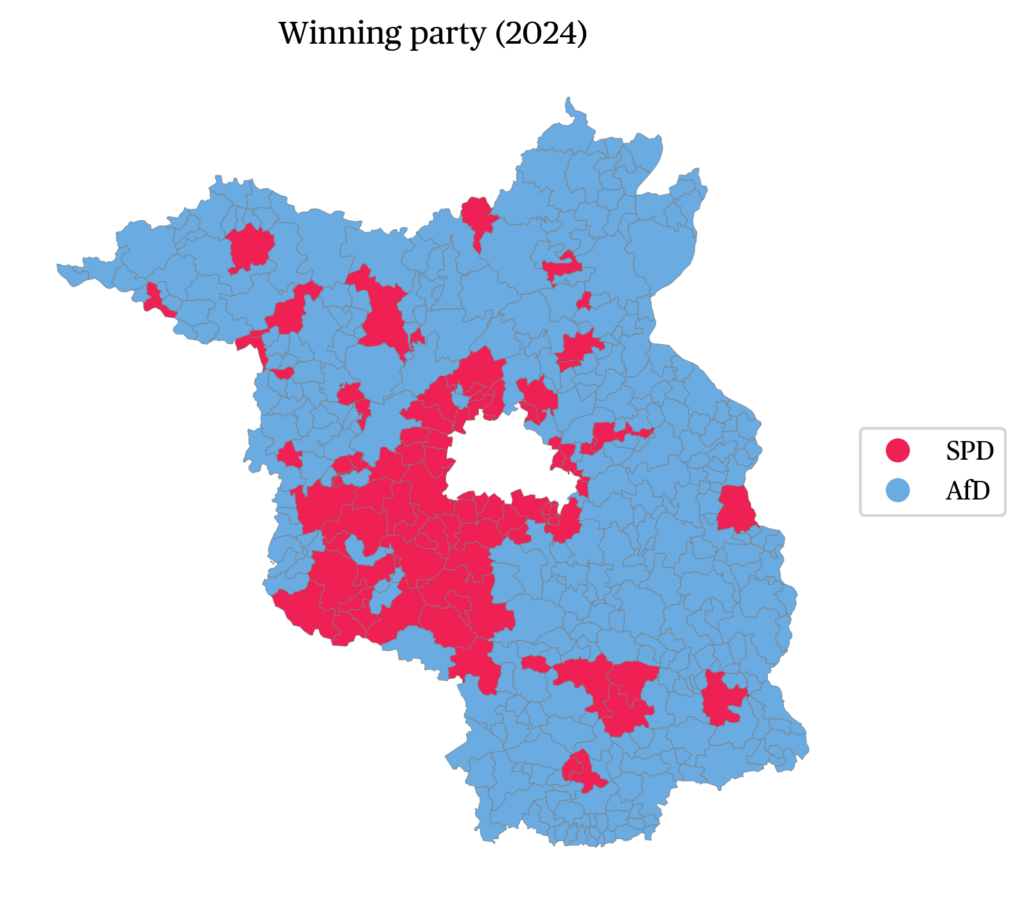

All of the direct mandates went to either the SPD, which won 19 constituencies – six fewer than in 2019 – or the AfD. The latter won ten new constituencies, bringing its total to 25 out of the 44 directly elected members of the state parliament.

The AfD performed best in sparsely populated, economically weaker districts such as Prignitz-I, as well as in Lusatia, a region where coal mining is still active. Its strongholds are mainly in the south near Saxony, in the east near the Polish border, and in the north.

From a demographic perspective, the election day survey conducted by Infratest dimap on behalf of ARD (Infratest dimap, 2024) revealed that the AfD was the strongest in all age groups under 60. This also applied to first-time voters, among whom the increase compared to the previous election was particularly strong (+13pp). Women were less likely to vote for the AfD than men (24% compared to 35%), though the gender gap was smaller than in previous elections. Similarly, significant differences in voting behaviour were observed according to level of education: the AfD performed significantly better among people with a lower level of formal education (35%) than among those with a higher level (22%) (Infratest dimap, 2024).

On the other hand, the SPD dominated in urban areas and performed better among women than the AfD. According to the election day survey, 49% of people aged over 70 voted for the SPD, compared to 17% for the AfD and 16% for the BSW. As 32% of Brandenburg’s population is aged over 60 (Berlin-Brandenburg Statistics, 2025), it is clear that this age group was pivotal in securing the SPD’s election victory.

Founded a year earlier, the BSW contested the 2024 European elections for the first time. With its blend of right-wing and left-wing populism, the alliance thwarted a victory for the AfD in Brandenburg. According to a post-election survey by Infratest dimap (2024), 31% of BSW voters would have voted for the AfD if the BSW had not been an option in the election. Voter migration also shows that all parties lost votes to the BSW.

The BSW performed best in the south-west and north-east of the state. In all age groups, it achieved results ranging from 12% (35- to 44-year-olds) to 16% (over 70-year-olds) (Infratest dimap, 2024). The party performed best in Lychen, Uckermark, a district close to the border with Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. One possible explanation for this result could be the Democracy Alliance, which was founded in this village of 3,400 inhabitants in 2023 in response to attempts by neo-Nazis to acquire land in the municipality. Since then, people have been gathering every two weeks to discuss the political situation. These discussions often focus on frustration with the established parties, as well as on arms deliveries and demands for negotiations with Russia. Many voters identified with Sarah Wagenknecht’s views, even though she was not standing for election herself (Tagesspiegel, 2024).

The Woidke factor

The significant growth of the SPD is primarily due to a noticeable change in sentiment in late summer: while the SPD and AfD made significant gains during this phase, the CDU and BSW lost popularity (Infratest dimap, 2024b).

A key success factor for the SPD in the 2024 state election in Brandenburg was the strong personalisation of the election campaign around Minister President Dietmar Woidke. Woidke presented himself as an experienced state leader and placed himself at the centre of the campaign. This strategy proved to be effective: according to election-day polls, 65 per cent of respondents considered Woidke to be a suitable prime minister, with a high approval ratings even among supporters of other parties. Notably, 52 per cent of SPD voters said they would not have voted for the SPD without Woidke as their top candidate (Infratest dimap, 2024).

Although this focus on personality was criticised by other parties, in a polarised race between the SPD and the AfD, many voters cast strategic ballots, choosing the SPD over smaller parties such as the Greens or Die Linke. This damaged the prospects of potential coalition partners and limited the SPD’s options after the election. The Greens in particular criticised the SPD for changing their position on asylum policy, accusing them of shifting to the right. Co-lead candidate Benjamin Raschke even accused the SPD of no longer acting as a bulwark against the AfD. However, given the Greens’ poor showing on election day, this critique clearly did not resonate with most voters.

Coalition formation and coalition agreement

After the election, the SPD had to reassess coalition options: the previous SPD-CDU-Green alliance lost its majority following the Greens’ exit. A red-black (SPD-CDU) coalition also fell short of a majority by one seat. Thus, only two majority options remained: SPD-BSW or – arithmetically – a coalition with the AfD, which all parties ruled out. As a result of this situation, the SPD entered talks with the BSW. The new coalition agreement was published on November 27.

Following the election, BSW leader Robert Crumbach reiterated their opposition to US missile deployments in Germany, insisting that a peace-oriented SPD stance was a precondition for talks. This demand is reflected in the preamble of the nearly 70-page agreement: ‘The war cannot be ended by further arms deliveries. We view the planned deployment of medium-range and hypersonic missiles on German soil critically. We need concrete proposals to return to disarmament and arms control.’ The agreement also emphasises reducing bureaucracy and digitisation, as well as providing economic and educational support, including free childcare and a focus on basic skills in primary schools. In terms of security policy, it includes plans to increase police staffing to 9,000. In terms of migration policy, it includes the stricter deportation of individuals without residency rights and the faster integration of those with prospects of staying. Regarding digital policy, the agreement promises: ‘Brandenburg will have no more “white spots” without fast internet and no more “grey spots” without fibre optics.’

Outlook

Together with the Saxony and Thuringia elections, Brandenburg’s results had far-reaching consequences at the federal level. In all three states, the significance of the populist AfD and BSW was cemented. The migration debate shifted sharply to the right – due not only to the AfD but also the BSW’s critical positions.

The disastrous results of the federal coalition parties (SPD, Greens, FDP) exacerbated the existing tensions within the “traffic light” coalition. Following their defeat in Brandenburg, the Greens’ federal leadership resigned. Six weeks later, the coalition collapsed, resulting in the holding of early elections in February 2025. Once again, these were dominated by migration issues.

Initially, the BSW seemed poised to gain national influence while Die Linke seemed to be becoming irrelevant. However, the February 2025 federal election disrupted this trend: with 4.97% of the vote, the BSW narrowly missed the 5% threshold, while Die Linke staged a surprise comeback with 8.8%.

The data

References

Infratest dimap (2024). Election-day poll for the Brandenburg state election. Tagesschau.

Infratest dimap (2024b). BrandenburgTREND Juli 2024. Infratest dimap.

Henke, K. (2024, 23 September). „Das hat nichts mit Putinversteher zu tun“: Wie Lychen zu Brandenburgs BSW-Hochburg wurde. Tagesspiegel.

Rada, U. (2024, 10 September). Grüne ergreifen Flucht nach vorn. Taz.

RBB (2024, 25 September). Robert Crumbach zum Brandenburger BSW-Fraktionsvorsitzenden gewählt. RBB.

Statistik Berlin-Brandnburg (2025). Population count on December 31, 2023. Statistik Berlin-Brandenburg.

citer l'article

Charlotte Kleine, Regional election in Brandenburg, 22 September 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue