Regional election in Bremen, 12 May 2023

Issue

Issue #4Auteurs

Matthias Güldner , Andreas Klee

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

The Bremen city state election as a special case among German state elections

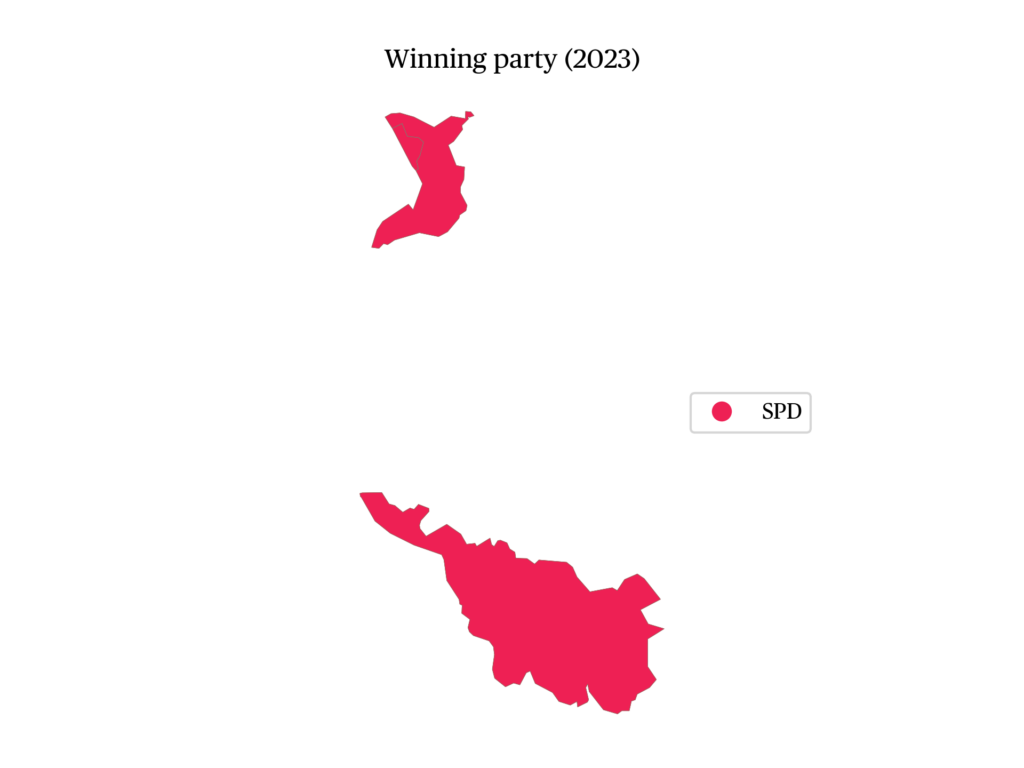

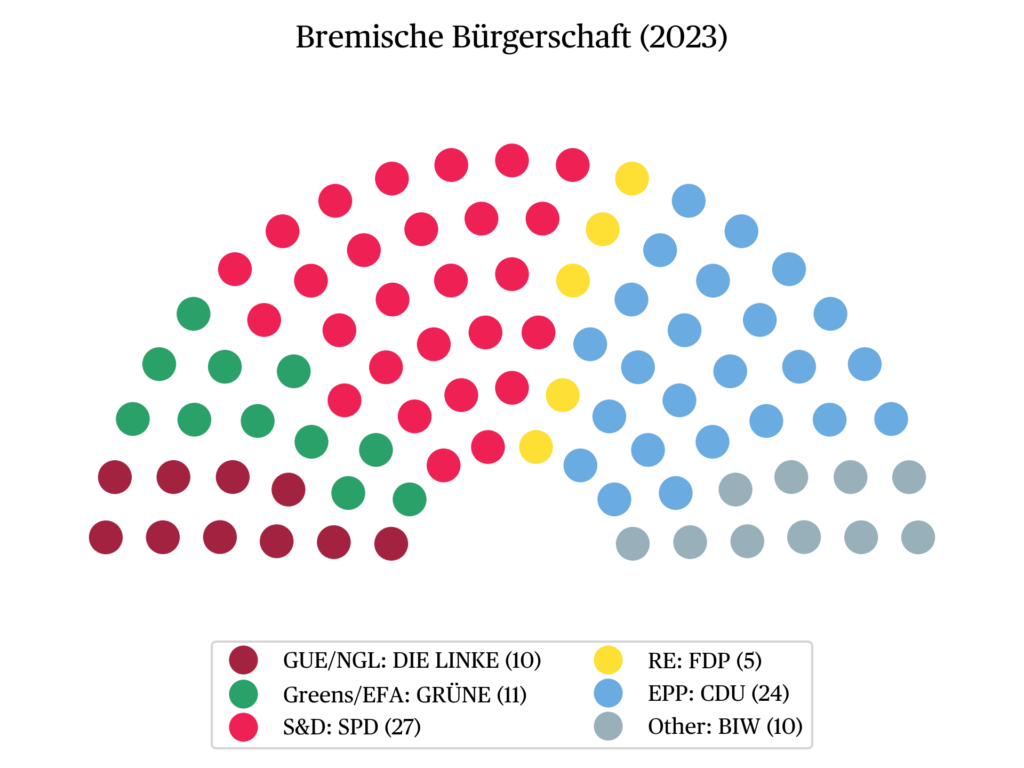

As the only two-city state among the German Länder, the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen occupies an intermediate position between territorial and city states. 1 The Bremen regional election is held separately in the two municipalities of Bremen and Bremerhaven, with the nomination of candidates and the application of the five-percent hurdle in each the two cities happening independently. Voters have a total of five votes, which they can distribute at discretion among party lists or individual candidates; they can eiether give all of their votes to a single candidate or split it among several candidates. In this way, voters can express their preference for specific coalition models and alter the list order proposed by the parties – an unsual feature in a regional election. This aspect of the electoral system favours the personalisation of election campaigns (Masch et al. 2023) by strengthening the role of the lead candidates (Spitzenkandidat*in) and encouraging candidates placed lower on the party lists to adopt a highly personalised campaigning style. Within the state parliament, the Bremische Bürgerschaft, the deputies from the constituency of Bremen form the municipal legislature (Stadtbürgerschaft). The same principle applies to the executive, with the Senate governing both the state and the city of Bremen in “personal union.” The voting age is 16 and parliamentary terms last four years – a unique case among the German Länder. The head of government, called ‘mayor’ and ‘president of the senate’, is merely primus inter pares and is directly elected by the Bürgerschaft like any other senator. He has no authority to issue directives and, like all members of the senate, can be dismissed at any time by a majority of Bürgerschaft members.

The political situation prior to the 2023 election

Since the 2019 election, Bremen has been governed by a coalition of the SPD (S&D), Bündnis90/Die Grünen (Greens/EFA) and Die Linke (GUE/NGL), hereafter referred to as the Red-Green-Red (RGR) coalition. 2 At the time of the election, the SPD was the biggest governing party and had been in government since 1946; the Greens had been co-governing the state since 2007; and the Left Party was the most recent party in governement, having joined the coalition in 2019. The opposition consisted of the CDU, which became the strongest party for the first time in 2019, the FDP, various AfD splinter groups that refused to work together as an AfD parliamentary group, 3 and the electoral association Bürger in Wut (Citizens in Anger) which took on individual AfD MPs in the course of the legislative term. Although the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen is represented in all German federal bodies, holds three votes in the Bundesrat and even entertains its own state representation to the EU, the political competition in the region is mainly shaped by local dynamics. In particular, the SPD’s dominant position in the region is largely idiosyncratic: popular mayor Andreas Bovenschulte (SPD) has dominated Bremen’s political scene for years at the personal level, while programmatically, his party has been able to set the tone within the coalition thanks to its long government experience and broad civil society network. However, it must be noted that fundamental conflicts within the coalition have become more visible since 2019 between the Greens on the one hand and the SPD and the Left on the other, mostly related to climate and transport policy issues.

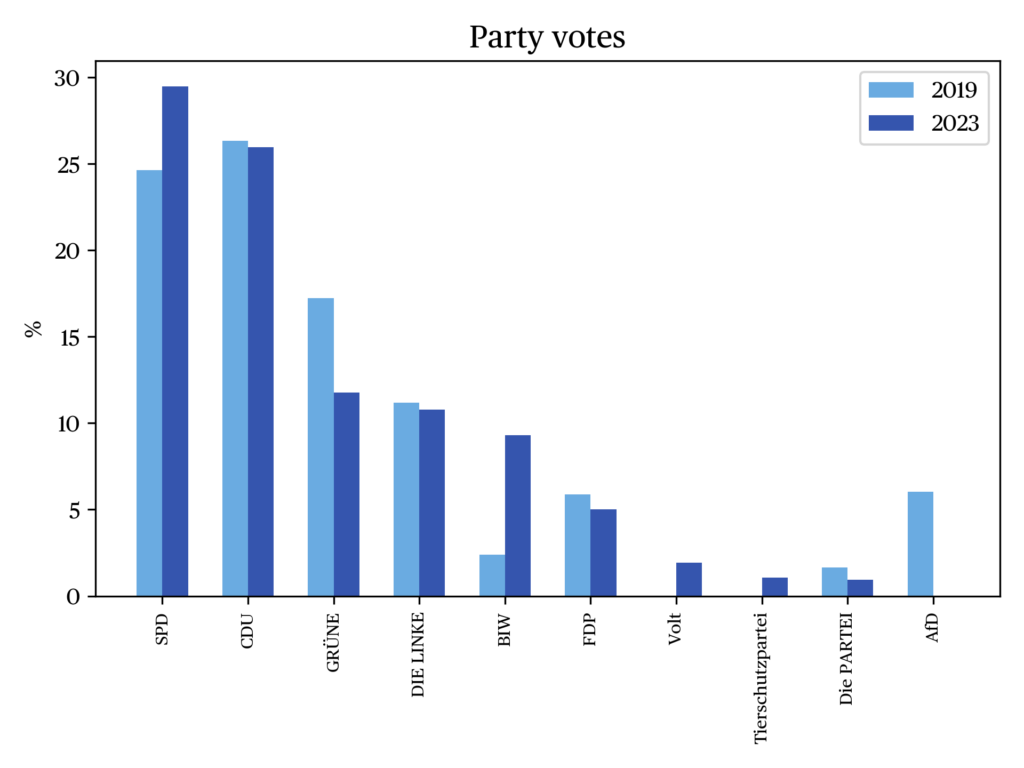

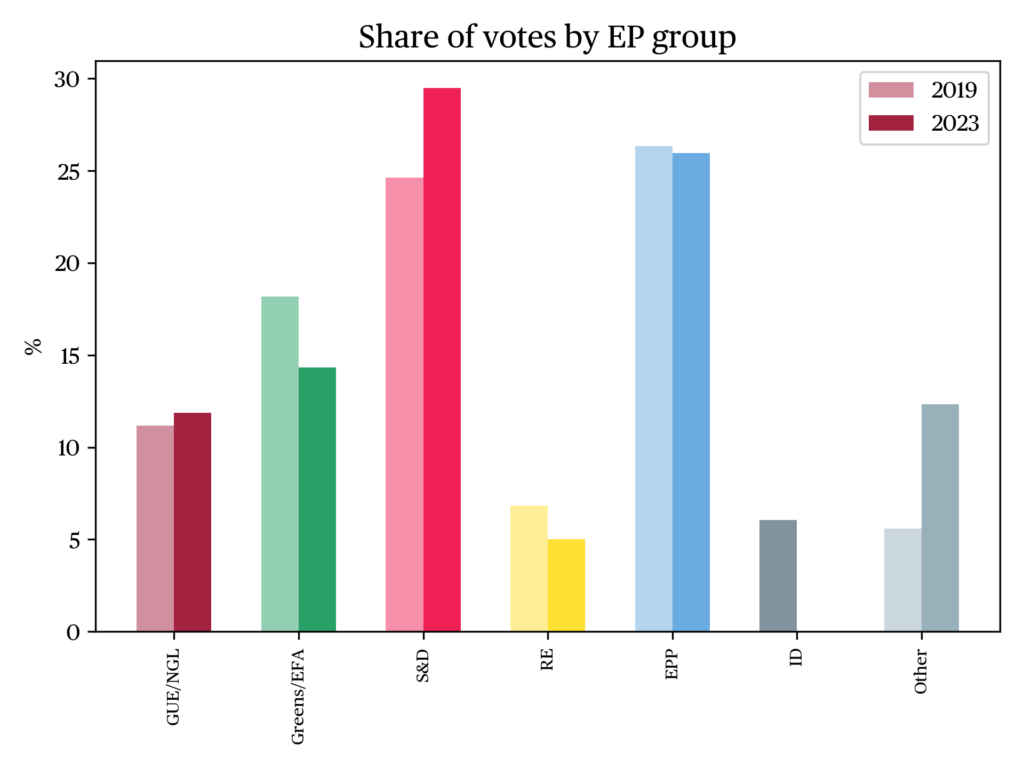

The election results in a nutshell

After significantly increasing its vote share (see “the data”), the SPD was able to regain its position as the state’s strongest party following the 2023 election. The vote shares of Die Linke, the CDU and the FDP remained stable, while the Greens, with a minus of over 5 percentage points, were the biggest loser of the election. Partly because the AfD was not allowed to stand in the election due to errors in the submission of their candidate list, the Bürger in Wut (Citizens in Anger, BIW) entered parliament with 10 deputies. Besides attracting ex AfD voters, the BIW benefited from widespread dissatisfaction with the coalition parties, but also with the CDU and FDP, who were perceived as insufficiently resolute in their role as opposition parties. As a consequence, all parties previously represented in the state parliament as well as the BIW, rebranded as “Bündnis Deutschland” (Alliance Germany), were able to form a fully constituted parliamentary group shortly after the election.

Turnout dropped down to 57% after an increase of around 14 percentage points in 2019 (64.1%). Traditionally, due to the extremely fragmented social structure in both cities, turnout is spatially very stratified and closely linked to the social status of the electorate. For example, turnout in the affluent district of Borgfeld in Bremen’s east was 81.0%, while in the nearby district of Tenever, dominated by large housing estates in the style of the French banlieues, it was only 32.4%. A more detailed analysis of individual constituencies reveals even greater disparities.

Analysis of the election results with special regard to the formation of coalitions.

On 25 May 2023, after exploratory talks with the previous coalition partners and the CDU, the Bremen SPD announced its decision to resume coalition negotiations with the Greens and the Left. The coalition agreement was eventually signed in Bremen on 3 July 2023. In order to address the concerns of many citizens that Bremen’s state politics would simply “carry on as before” with the same coalition in power, the SPD’s decision was accompanied by a statement promising a “clear shift” in government policies (Metzner 2023).

The Electoral Success of the Voters’ Association Citizens in Anger (BIW)

The BIW is an electoral association founded in 2004 that has so far only attracted attention in the two-city state of Bremen, where it has been especially prominent in the municipality of Bremerhaven. In recent years, the BIW have repeatedly benefited from internal AfD squabbles and have been able to form parliamentary groups consisting of up to three MPs as a result of the defection of several former AfD members. In the party spectrum, the BIW can be classified as right-wing populist (Metzner 2023). They describe themselves as being to the right of the CDU and to the left of the AfD (Stegemann 2023).

When looking at voter transitions towards the BIW, 4 two major groups stand out. On the one hand, about 6,500 ex AfD voters switched to the BIW, which means that about one third of the increase in the BIW’s vote is due to the AfD not being able to compete in the election. 5 The two remaining thirds (12,000 voters) are due to losses by the other parties represented in parliament and to the vote of previous non-voters or new voters.

The BIW’s electoral success also impacted the coalition formation process. The BIW winning 10 mandates was a shock for the other parties. For the governing coalition, it is a clear signal of growing dissatisfaction with the work (not) being done by the government: Bremen’s voters show increased readiness to sanction what they perceive as bad government performance through drastic voting decisions. For this reason, pressure has been mounting on the coalition to document the promised change in the coalition agreement. The need to establish a narrative of “business as usual, without business as usual” has already been reflected in personnel decisions. 6 These are certainly not exclusively due to the success of the BIW. However, the latter reinforced the image of a unsuccessful government, although this did not impact all government parties to the same degree.

The significant losses of Alliance 90/The Greens

The party, which was confronted with high expectations both internally and from its electorate, was given the sole responsibility for the government’s poor performance. The few policy areas in which the senate was able to assert itself in this term dominated by the Covid-19 pandemic, such as public health (Die Linke) or internal security (SPD), were not led by the Greens. In addition, Andreas Bovenschulte successfully presented himself as the government’s dominant personality through skilful public relations (‘Bremen vaccination successes’, ‘introduction of an excess profits tax’), thus further reinforcing his prime ministerial bonus. In the run-up to the election, the Greens’ poll ratings 7 dropped drastically on both the personal (senators) and the substantive level (satisfaction, competence attribution). In fact, the low level of overall satisfaction with the work of the senate (41%) was clearly undercut by the Greens’ score (only 20% were satisfied with their work). The Green lost support in all policy areas. In particular, in their core area of ‘climate and environmental policy’, the Greens suffered a drastic loss in competence attribution of 24 percentage points (from 61% down to 37%). Furthermore, ‘climate and environmental policy’ was rated as less important by voters in comparison with to the 2019 election.

While Andreas Bovenschulte reached a 70% rate of approval, Maike Schaefer was the most unpopular lead candidate of any party running in the election. In the end, the Greens lost 15,000 voters to their coalition partners (SPD: 10,500 / Die Linke: 4,500).

This result gave the SPD a very strong bargaining position during the coalition negociations, despite the party having obtained its second-worst score in history with 29.9%. Thanks to its slight increase in vote share and the Greens’ weakness, the party could assert itself more confidently. The Greens, who, as the perceived winners of the 2019 election, were able to influence the previous executive’s agenda significantly, are now paying a high price for their electoral defeat. Overall, the Greens lost the portfolios of transportation (mobility), construction, urban development, social affairs, integration, youth and sport, while obtaining a single new portfolio, science.

Federal consequences of the 2023 Bremen election

In view of the unique features of what is probably Germany’s most peculiar federated state (Probst et al. 2022), the lessons of the Bremen regional vote cannot be readily generalized to other states or the federal government. Nevertheless, after weighting local peculiarities, some findings of supraregional interest can be highlighted.

The dismantling of the climate and environment department, which previously also included transportation and urban planning, can be seen as a sign that the Greens’ coalition partners want to reverse the trend, perceptible both at federal level and in other states, of merging traditionally well-established policy areas (such as the economy or transportation) under the umbrella of the fight against climate change.

Even more than is usual in state politics, which is often described as a “prime minister’s democracy”, the overwhelming influence of the personal factor on voters’ decisions became clear in the election results. In opinion polls, the incumbent mayor achieved an approval rating of 70% (very satisfied/satisfied). 8 Looking at the election results of the 14 May 2023 ballot, the SPD’s lead candidate alone gathered more individual votes (141,420) than the whole Green Party list (128,442). The SPD’s highly candidate-centric campaign strategy, which even saw Bovenschulte sing and play guitar at political meetings, has paid off.

In view of the precarious state of the so-called ‘traffic light coalition’ at federal level in the early summer of 2023, the sustainability of three-party coalitions is increasingly disputed in Germany. In the RGR coalition in Bremen, the strongest political force, the SPD, had significantly more opportunities to assert itself than within the two-party Red-Green coalition in the three previous election periods. Although the negative image of a quarrelling coalition is likely to have negatively impacted the SPD’s electoral performance, its attitude as a balancing factor, a “voice of reason” and a moderator vis-à-vis the more extreme positions of its junior partners eventually proved successful.

In the 2023 parliamentary elections, the Greens were “squeezed” between the radicalising positions of climate activists, the core clientele of the party, and the growing resistance of broad sections of the population to demands for increasing individual contributions to climate protection. Federal policy issues such as the “heat pump debate” and state policy measures that were perceived as directed against urban car traffic (“Brötchentaste” – a policy that allowed short-term parking while “at the baker’s”) converged to shape a dominant political trend that strongly affected the Greens’ poll ratings and election results. A comprehensive party strategy to address this challenge in a multi-level political system is not yet in sight.

Whereas in a relatively young party like the Greens, signs of wear and tear in terms of both personnel and political programme may appear inevitable after four election periods in government (a nationwide record for the Greens), the SPD, which has been in government uninterrupted since 1946, is much more resilient in the face of criticism. Despite the poor performance of Bremen’s government in core policy areas when compared to the rest of the country, these poor ratings have hardly affected the governing SPD’s standing. Indicators of poor government performance include the highest unemployment rate, the greatest risk of poverty and, most importantly and consistently over time, the worst-performing educational system of all German states. Among other factors protecting the SPD, the so-called school consensus (Schulfrieden) concluded for the 2008-2028 period, and which the opposition CDU also signed, contributes to shielding the SPD from attacks related to education policy.

The CDU, on the other hand, was unable to expand its historic electoral success of 2019. Looking more closely at the historical development of Bremen’s CDU, the party appears to be primarily concerned about its appeal to the mainstream of a left-liberal metropolitan audience. This strategic orientation leads the party to exercise great caution and restraint on issues perceived as potentially left-antagonising, such as internal security, migration or drug policy. This defensive approach does not encourage demands for political change among the population. This may explain part of the difference between the performance of the CDU in Bremen, in Berlin and at federal level.

The formal exclusion of the AfD and the participation of the BIW, which is only active in Bremen, are unique features of this state election. Nevertheless, the great electoral success of the BIW deserves nationwide attention. The merger of the voters’ association into a new ‘Alliance Germany’ with a parliamentary group in at least one state legislature can be read as an intent to fill a new space in the party spectrum between the CDU/CSU and the AfD. If it is able to expand nationwide following its local success in Bremen, the BIW could influence Germany’s political system as a whole.

The Data

References

ARD (2023). Wie die Wähler in Bremen wanderten. ARD.

Bullwinkel., B. (2022). Die CDU in Bremen. In Probst, L., Güldner, M. et Klee A. (éd), Politik und Regieren in Bremen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 181-196.

Güldner, M. (2022). Die Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Bremen. In Probst, L., Güldner, M., & Klee, A. (eds.), Politik und Regieren in Bremen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 247-256.

Masch, L., Gaßner, A., Klein, M., & Rosar, U. (2023). Physische Attraktivität und Personalisierung des Wahlverhaltens. Ein Vergleich der Bundestagswahlen von 2002 bis 2017. In Ackermann, K., Giebler, H., & Elff, M. (eds.), Deutschland und Europa im Umbruch. Wahlen und politische Einstellungen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS..

Metzner, F. (2023, 25 May). Weiter so oder Neuanfang? SPD, Grüne und Linke wollen Koalition formen. Buten un binnen.

Probst, L., Güldner, M., & Klee, A. (eds.) (2022). Politik und Regieren in Bremen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Probst, L. (2022). Bremische Bürgerschaftswahlen von 1946 bis 2019. In Probst, L., Güldner, M., & Klee, A. (éd), Politik und Regieren in Bremen. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 247-256.

Stegemann, J. (2023, 16 May). Der Mann, der mit Wut für Recht und Ordnung wirbt. Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Notes

- On the political system of the Free Hanseatic City of Bremen, see Probst, Güldner, & Klee (2022).

- For details about the 2019 election see Probst (2022 : 315).

- On the failure of the AfD, which originally started out with a parliamentary group, see Güldner (2022).

- All data on voter migration here and elsewhere are from infratest-dimap for the ARD.

- The AfD was not able to agree internally on a list of candidates within the time limit of the admission procedure to the election and, as a result, submitted two different lists. This was deemed inadmissible by the state election committee, whereupon neither of the two lists was admitted. The AfD was thus not qualified for the state election, except in the election for the city parliament in Bremerhaven, which took place at the same time. The AfD has filed a complaint with the Election Review Court (Wahlprüfungsgericht). In final instance, it would be decided by the Bremen State Court (Staatsgerichtshof Bremen). Observers believe that the lawsuit’s chances of success are slim, since appeals by the AfD factions against the exclusion had already been rejected before the election.

- Both the top candidate of Bündnis 90/ Die Grünen and former Senator for Climate Protection, Environment, Mobility, Urban Development and Housing, Maike Schäfer, and Anja Stahmann (Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen) former Senator for Social Affairs, Youth, Integration and Sport have announced their retirement from politics. The state chairpersons of the Greens have also announced their withdrawal.

- All survey data used from infratest-dimap LänderTREND (March-May 2023).

- Data: Infratest-dimap LänderTREND, March 2023.

citer l'article

Matthias Güldner, Andreas Klee, Regional election in Bremen, 12 May 2023, Nov 2023,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue