Regional election in Galicia, 18 February 2024

Issue

Issue #5Auteurs

Nieves Lagares Díez , María Pereira Lopez

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

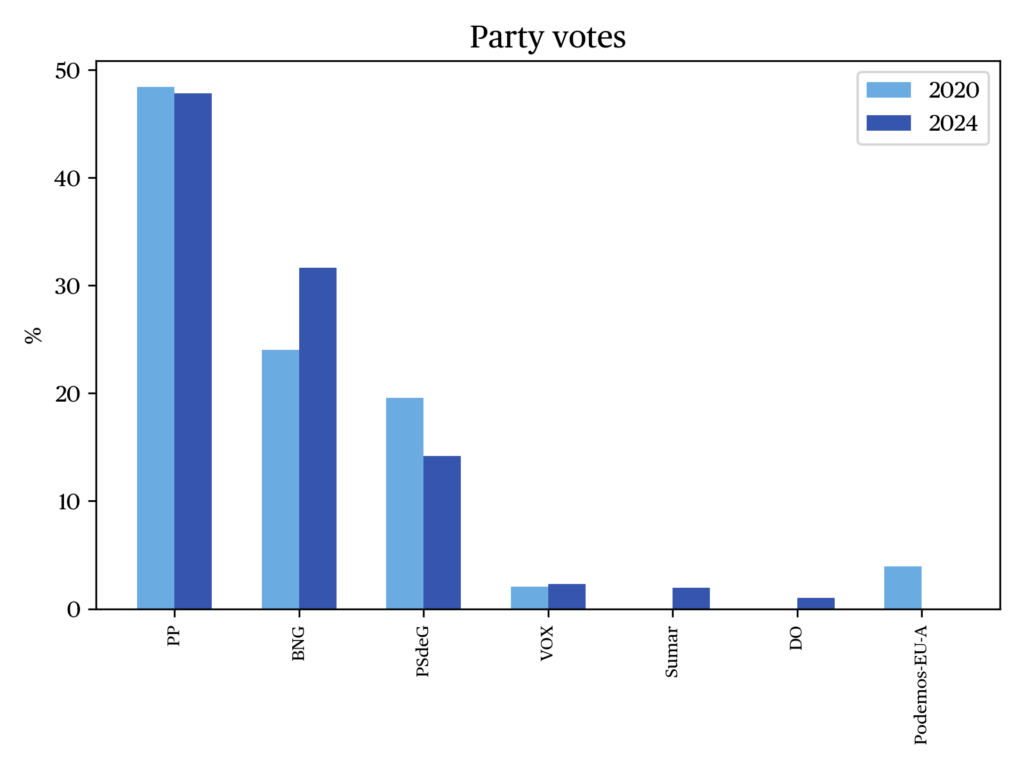

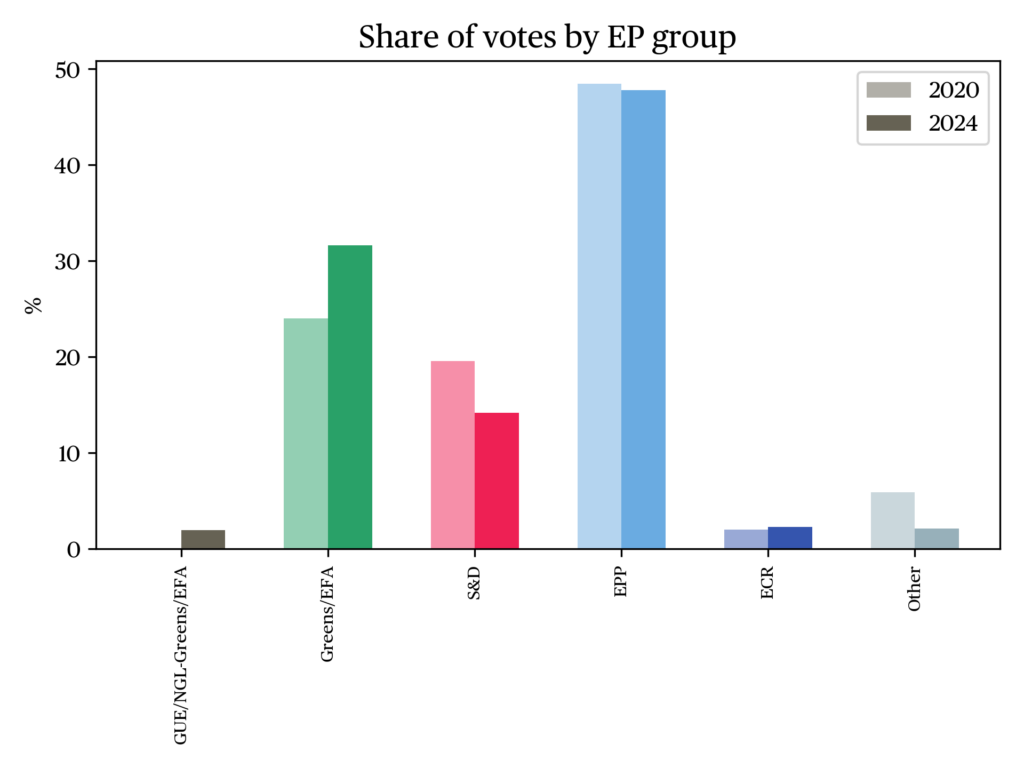

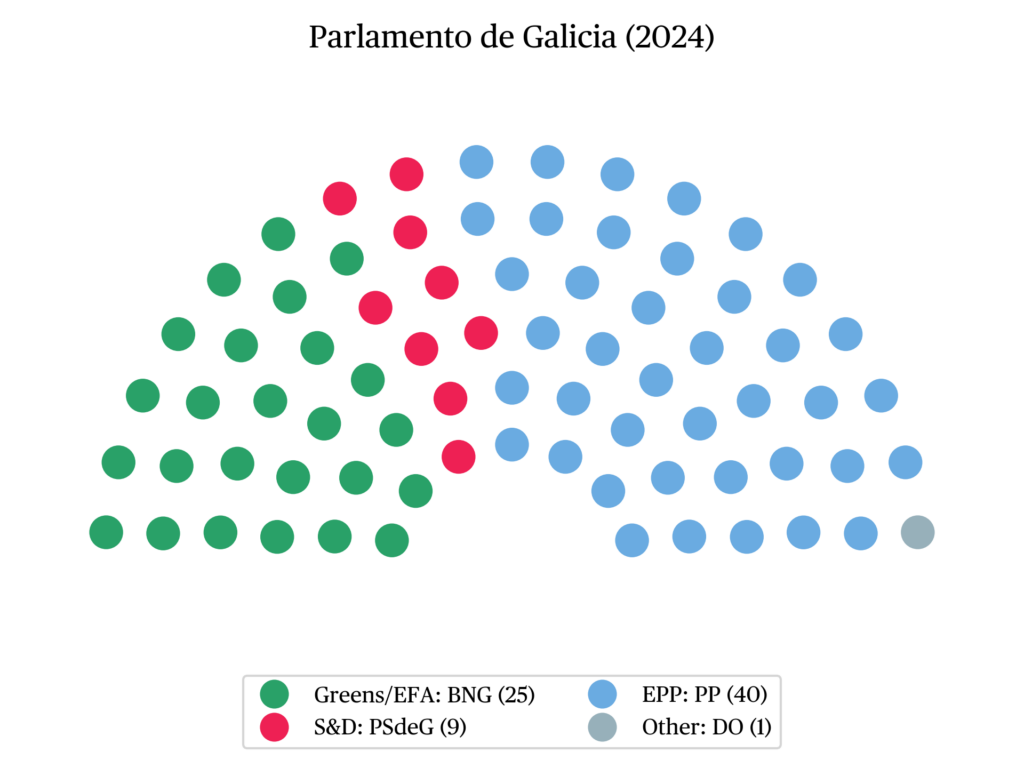

On February 18, 2024, autonomous elections were held in Galicia, marking the beginning of the twelfth regional legislature. In this election, the People’s Party of Galicia (PPdeG) once again emerged as the leading political force, winning 47.39% of the vote and a total of 40 seats, thereby securing its ninth absolute majority since the beginning of the autonomous era. Despite opinion polls suggesting a potential shift in power due to the rise of the Galician Nationalist Bloc (BNG), the Galician Socialist Party (PSdeG) was relegated to third place, while the PPdeG maintained its political hegemony in the region, once more confirming the effectiveness of its organisational apparatus (Lagares, 1999, 2003). Alfonso Rueda, the party’s candidate, was thus elected president of the region, attaining the long-sought legitimacy for a position he had held since March 2022 following the early resignation of his predecessor, Alberto Núñez Feijóo.

Galicia, one of the three historic communities

Galicia, along with Catalonia and the Basque Country, forms part of the so-called “historical nationalities,” 1 whose political and social past, marked by aspirations for autonomy before Spain’s democratic transition (1975), was specifically recognized in the 1978 Spanish Constitution. This recognition, enshrined in Article 151 of the Constitution, granted these regions expedited and enhanced access to autonomy, unlike other communities governed under the ordinary process (Article 143). This status conferred upon them a higher level of devolved powers. 2

From a legal perspective, the Galician electoral system rests on the same principles as most regional electoral systems in Spain. The 75 3 seats of the Galician Parliament are elected by direct universal suffrage through closed lists in four constituencies corresponding to the Galician provinces: A Coruña (25 seats), Lugo (14), Ourense (14), and Pontevedra (22). This division leads to an electoral imbalance that reflects the pronounced socio-economic disparities between the less populated inland provinces and the coastal provinces. 4 Two key demographic factors of the autonomous community must be noted, as they are decisive in understanding the results obtained by certain parties: on one hand, the high dispersion of the population, particularly evident in the inland provinces; and on the other, the significant population concentration around the seven major cities and their surrounding areas (A Coruña, Ferrol, Lugo, Ourense, Pontevedra, Santiago de Compostela, and Vigo) 5 . The electoral system establishes a 5% threshold of votes at the constituency level to participate in the allocation of seats.

The Mechanisms of a Unique Party System

Galicia has developed its own political and party system, structured around three elements: the hegemonic presence of a single party (Lagares, 1999, 2003), the absence of a strong and structured right-wing nationalist movement such as those in Catalonia or the Basque Country (Lagares, Rivera and Máiz, 2012), and a persistent fragmentation of the left over the identity question (nationalism vs. non-nationalism) 6 .

The first factor pertains to the competitive dynamic between the three main Galician political forces (PPdeG, PSdeG, and BNG) 7 in a political space electorally dominated by the PPdeG, with a fluctuating alternation between PSdeG and BNG as the second and third forces. This landscape forms an imperfect bipartisanship or a “two-and-a-half-party system,” where the left alternates in the opposition. Since 1981, the PPdeG has led every regional election, governing without interruption 8 (Márquez, 2014), except during two periods: the tripartite PSdeG-CG-PNG/PG coalition (1987–1989) 9 and the PSdeG-BNG bipartite government (2005–2009). This dominance has enabled the PPdeG to develop a coherent political project over more than thirty years 10 , with a style distinct from the national party, crowned by nine absolute majorities since 1989 11 . The 2024 elections, except for those of 2005, represented the most serious threat to this hegemony, with a BNG in full ascent under Ana Pontón. However, the results once again underscored the PPdeG’s organisational strength (Lagares, 1999, 2003), whose victory was based less on an identifiable leadership than on the strength of its party brand (Gómez, 2020).

The second defining feature of this party system is the absence, unlike in Catalonia and the Basque Country, of a strong right-wing nationalist party. Instead, a left-wing nationalist party has progressively established and consolidated itself in Galicia, albeit without reaching the electoral success of right-wing formations in the aforementioned communities. This can fundamentally be attributed to two factors. First, the PPdeG’s early integration of small right-wing nationalist actors at the start of the autonomy process prevented their atomisation and consolidated unity within this political spectrum. This factor partly explains the absence of the far right in the Galician Parliament. Second, within the PPdeG there has existed a distinctive and cross-cutting political style (Ares and Rama, 2019), developed for years around a central axis: a sui generis nationalism (Barreiro, 2016), which has become a defining feature of the party’s identity (Rivera, 2003), incorporating a strong Galicianist content into its political program (Lagares, 1999, 2003).

The third explanatory factor is the persistent internal ideological rifts of the left on questions of identity and nationalism, which has prevented the formation of lasting alliances capable of building governing majorities. 12 The continuous presence of PPdeG, PSdeG, and BNG in Parliament since 1989 was interrupted only twice: in 2012, with the coalition Alternativa Galega de Esquerda (AGE), bringing together various left-wing nationalist forces (Anova, Esquerda Unida, Equo Galicia, Espazo Ecosocialista Galego) 13 ; and in 2016, with En Marea, a Galician confluence inspired by Podemos. Following significant internal discord, En Marea disbanded ahead of the 2020 elections, resulting in the separate candidacies of Marea Galeguista (Marea, CxG, and the Galician Party) and Galicia en Común (Podemos, EU, Anova, and various local Mareas). The back-and-forth of left-wing nationalism in the Galician context would find a certain resolution in this electoral process; for although Galicia en Común received votes in the last election, it failed to surpass the electoral threshold this time and thus disappeared from the parliamentary scene.

Party Competition in the 2024 Galician Autonomous Elections

Three dynamics shaped the political competition in the February 18, 2024, elections, beyond the structural features of the electoral system built over 43 years of autonomy: the renewal of leadership within the PP, the strategic consolidation of the BNG, and internal difficulties within the PSdeG. Each is examined in turn.

President Alfonso Rueda’s (PPdeG) announcement of early elections on December 21, 2023, did not come as a surprise to the opposition. Rueda had succeeded Alberto Núñez Feijóo, who had led the region since 2009 before departing for national politics to stand as the PP’s candidate in the 2023 general elections, an election also called early and unexpectedly by the Prime Minister and PSOE leader, Pedro Sánchez. Against this backdrop, and amid persistent rumors of early regional elections since 2022, many interpreted Rueda’s decision as not only an attempt to capitalize on national political momentum, particularly the debate and adoption of the amnesty law, to the detriment of the left, but also as a means of consolidating his leadership over both the regional government (the Xunta de Galicia) and his party. Once again, the PPdeG successfully deployed a powerful electoral machine to support a tailored strategy for a new, technocratic leader who from the outset understood his role, adhered strictly to the planned narrative, and avoided missteps.

As for the BNG, the party approached the election aiming to consolidate a political and electoral strategy launched in 2016 with a change in leadership and brought to maturity in this contest. 14 Amid the turbulence that had afflicted the left-wing ideological spectrum since 2012, the BNG sought to absorb the political failure of emerging leftist projects by capturing new generations of voters who, as in other historic communities, were turning to left-wing nationalist options. The frontist formation aimed to promote a renewed, emotional, and cross-cutting discourse capable of attracting new center-left voters and securing sufficient support to govern the region. Despite a well-conceived and robust campaign and a leader with strong electoral appeal, certain programmatic ambiguities—rooted in the party’s identity tradition—prevented the much-anticipated success, despite a strong showing.

Finally, the PSdeG, under the leadership of José Ramón Gómez Besteiro, 15 faced a serious internal crisis and the uncertainty of an election that offered insufficient time to build and stabilize its positioning. The Socialist Party has long been characterized by ongoing reconfiguration, lacking a solid and clearly established organisational structure at the regional level. Since 2009, it has been marked by improvised leaderships which, once again, proved unable to meet the demands of a decisive election.

To these three elements must be added a decisive factor that undeniably marked this electoral process: the intense and unprecedented nationalization of the campaign in the region. Beyond situational dynamics, chiefly the crisis over the spill of plastic pellets along the Galician coast 16 and the opposition’s accusations of mismanagement against the Xunta, the defining feature of the campaign was its nationalization. The leaders of Spain’s two main national parties, Alberto Núñez Feijóo (PP) and Pedro Sánchez (PSOE), personally took charge of the campaign with an unprecedented presence in a regional election. Both, due to internal dynamics within their respective parties and the perceived weakness of their regional candidates, heavily involved themselves in the process, seeking to capitalize on it. Yet once again, Galicia’s political arena demonstrated its distinctiveness, revealing the ineffectiveness of campaigns designed and led from Madrid. Since the PP’s first campaign as Alianza Popular (“Galego coma ti”) 17 , the party (later the PPdeG) has better than anyone managed to territorialize the electoral campaign and dissociate it from national logic. Once again, all parties missed the opportunity to highlight specifically Galician issues in the campaign, thereby undermining its truly autonomous nature.

The Results of the 2024 Autonomous Elections: The Territorial Factor

The elections for the twelfth Galician autonomous legislature recorded a moderate turnout (56.27%), though higher than that of 2020, which took place at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. As noted above, the PPdeG emerged victorious once again with 47.39% of the vote and 40 seats, securing an absolute majority despite losing 2 seats compared to the previous elections. The BNG came in second with 31.34% of the vote and 25 seats, yet failed to garner sufficient support for its leader, Ana Pontón, to become the first woman to preside over the Xunta. Galician nationalism did not achieve the hoped-for breakthrough, despite the efforts invested in the campaign. The PSdeG collapsed, losing as many as five deputies and recording the worst result in its history in the community (16.7%, 9 seats). To this picture must be added Democracia Ourensana (DO), a party rooted in the city of Ourense, which succeeded in capturing a seat from the PPdeG in that province, thus becoming the fourth parliamentary force in Galicia. Sumar and Podemos, which had announced separate candidacies a few months earlier 18 , failed to obtain any representation. The same can be said of the far-right party Vox, which remains excluded from the only regional parliament in Spain that continues to resist it, partly for the reasons discussed above.

The distribution of votes by province among the main parties changed little compared to previous elections, largely mirroring the regional results with only minor variations. The PPdeG remained the most voted party in all four provinces, with a strong presence in Lugo and Ourense (its traditional strongholds) and notable growth in the provinces of A Coruña and Lugo. Since 2016, the BNG has seen significant gains across all provinces, particularly in the Atlantic provinces (+7.61 percentage points in A Coruña, +9.77 in Pontevedra). The PSdeG, by contrast, experienced a sharp decline everywhere (–17.59% in A Coruña, –15.44% in Lugo, –19.43% in Ourense, –15.77% in Pontevedra), continuing the downward trajectory that began in 2009, despite a slight recovery in 2016 and 2020 in Ourense and Pontevedra.

In the seven major cities, the PPdeG lost some ground in A Coruña, Ferrol, Ourense, and Santiago de Compostela (–1 to –3 points), but made gains in Pontevedra and Vigo (+1 to +3 points), and especially in Lugo (+7 points compared to 2020). The BNG registered strong growth across all cities (A Coruña: +8.8%, Ferrol: +9.21%, Lugo: +3.14%, Ourense: +6.3%, Pontevedra: +6.99%, Santiago de Compostela: +8.39%, Vigo: +3.14%). The PSdeG declined in all cities except Lugo, where it maintained its 2020 result.

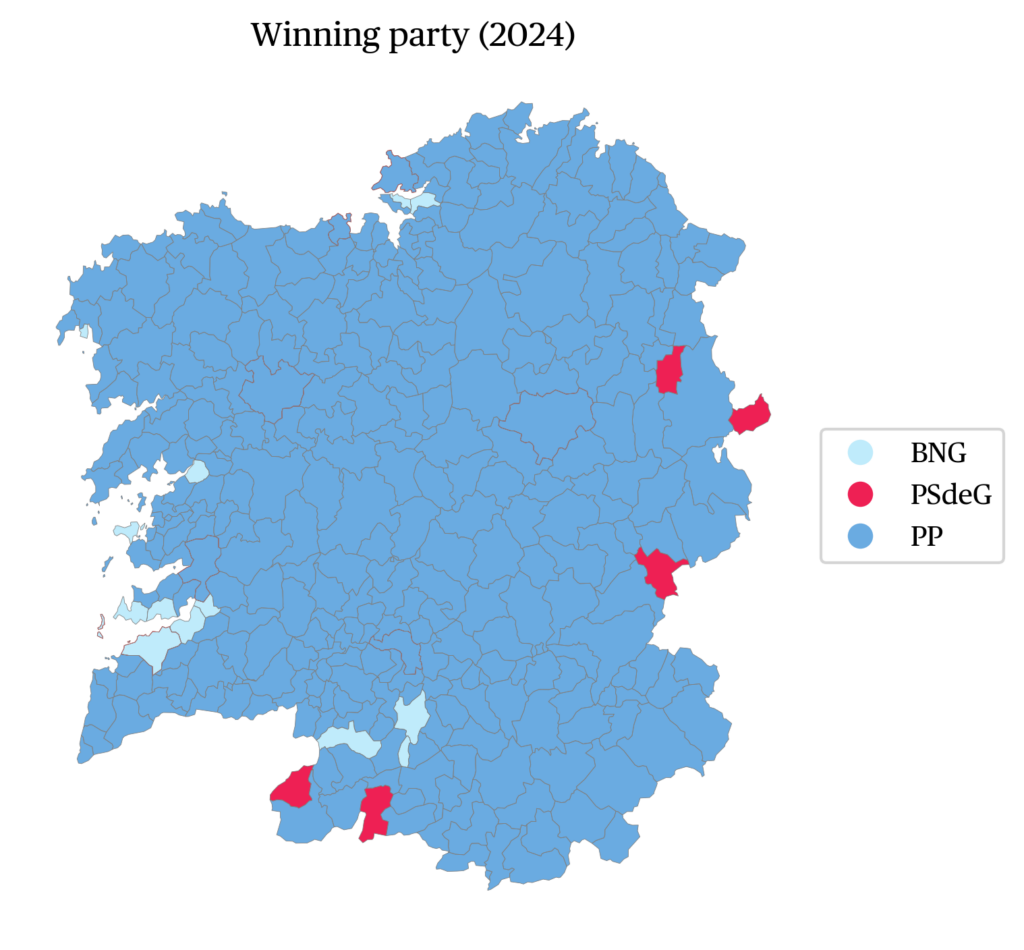

When analyzing the distribution of votes for the three main political parties in the autonomous community according to population density, several significant differences emerge, consistent with previously observed trends. The PPdeG enjoys strong support in the most rural and sparsely populated areas, sometimes reaching as much as 80% of the vote. Such dominance has been a hallmark of rural Galicia throughout the autonomous era. Conversely, in areas with densities between 1,000 and 2,000 inhabitants, its share drops noticeably, a trend also evident in the most urbanized areas (4,000 to 5,000 inhabitants). Another of its strongholds lies in semi-urban areas, with 2,000 to 4,000 inhabitants, where it can garner up to 70% of the vote.

The PSdeG, for its part, concentrates most of its support in areas with a density between 2,000 and 4,500 inhabitants, similarly to the PPdeG. However, unlike the conservative party, it fails to establish itself in the least populated municipalities.

As for the BNG, it achieves significant results (between 30% and 45% of the vote) in low-density areas (up to 2,000 inhabitants), suffers a clear decline in semi-urban zones, and then experiences marked growth in the most densely urbanized sectors (over 5,000 inhabitants). These dynamics are also visible in electoral maps showing the winning party by municipality. It is important to note that these maps clearly indicate that PPdeG support exceeds 30% in almost all Galician municipalities, with strong backing for the regional government ranging between 50% and 75% in most of them (see map).

Electoral Indices and the Configuration of the Party System

Electoral indices offer a quantitative lens through which to interpret the political competition observed in these elections. Using the Gallagher index of disproportionality, the Rae index of fragmentation, and the total volatility indicator, we can clearly understand the current configuration of electoral competition in Galicia.

The disproportionality index decreased from 6.30 in 2020 to 5.18 in 2024. The Effective Number of Electoral Parties (ENEP) slightly declined to 2.91, down from 3.1 in 2020, indicating a mild decrease in electoral competition. Notably, this is the lowest figure recorded since the upward trend observed from 2012 onward, which ranged between 3 and 3.5.

Unlike previous elections, this electoral trend did not translate into increased parliamentary fragmentation. The Effective Number of Parliamentary Parties (ENPP) this time stands at 2.44 which is a figure slightly below the average recorded since 2005 (2.57). Simultaneously, the degree of fragmentation (measured in votes) rose marginally from 0.33 in 2020 to 0.34 in 2024. The combined vote share of the two main parties in 2024 (PPdeG and BNG) reached 78.76%, up from 71.75% in 2020, indicating a high level of concentration in the party system. The total political volatility index was 18.79 in 2024 (in terms of vote share), compared to 22.90 in 2020, which had represented the highest level since the 2005 elections (inclusive).

According to Sartori’s classic typology (2005), the Galician party system can be classified as an imperfect bipartisanship—comprising one to three parties and characterized by stable, single-party governments, except for the tripartite government (1987–1989) and the PSdeG-BNG coalition government (2005–2009). As Lagares (2024) notes, this system has undergone five phases, defined by the electoral dynamics and the resulting governments, which correspond to cycles of vote dispersion and concentration.

Conclusions

These autonomous elections inaugurated the PP’s tenth legislature, now led by a new president, Alfonso Rueda—the fourth since the beginning of the autonomy and the third since the party’s first absolute majority. The coming years will determine the solidity of this leadership, which, unlike his predecessors, is built less on a personal figure and more on the success of public policies. It remains to be seen whether he will be able to position himself in an increasingly demanding national framework, where the party leadership expects its regional presidents to align closely with the central leadership’s strategy.

As for the BNG, one of the major questions left unresolved by this election is whether the project led by Ana Pontón since 2016 has reached its limit, or if it can continue to broaden its electoral base in future contests. To do so, the candidate will need to address certain internal dynamics within her party, particularly concerning linguistic and identity issues, in order to expand her support toward a center-left electorate.

Finally, the PSdeG enters a long and difficult period, one that will require consolidating its organisation, renewing its leadership, and defining a direction capable of taking control of the party and approaching future elections with the goal of regaining lost ground.

The data

References

Ares, C., & Rama, J. (2019). Las elecciones al Parlamento de Galicia (1981-2016): la importancia de la estrategia de transversalidad del PPdeG. In B. Gómez, S. Alonso, & L. Cabeza (eds.), En busca del poder territorial: cuatro décadas de elecciones autonómicas en España (pp. 303–330). Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

Barreiro, X. L. (2016). Por qué Galicia llegó a ser un sitio distinto. In M. Cheda & L. López (eds.), La era Feijóo. Elecciones gallegas 2016 (pp. 8–19). A viva voz.

Gómez, R. (2020). Votando al Partido Popular de Galicia: análisis de los componentes del voto a la formación en las elecciones autonómicas (1993-2016). Revista de Investigaciones Políticas y Sociológicas, 19(2), 85–106.

Lagares, N. (1999). Génesis y desarrollo del Partido Popular de Galicia. Tecnos.

Lagares, N. (2003). O Partido Popular de Galicia. In J. Manuel Rivera (ed.), Os partidos políticos en Galicia (pp. 368–427). Xerais.

Lagares, N. (2024). La evolución del sistema de partidos de Galicia. Cahiers de Civilisation Espagnole Contemporaine, 4.

Lagares, N., Pereira, M., & Rivera, J. M. (2018). De Podemos a las confluencias. In F. J. Llera, M. Barras, & J. Montables (eds.), Las elecciones generales de 2015 y 2016 (pp. 227–248). Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

Lagares, N., Manuel Rivera, J., & Máiz, R. (2012). Le nationalisme galiciende l’accès au gouvernement à la crise électorale et organisationnelle. In A. Fernández & M. Petithomme, Les nationalismes dans l’Espagne contemporaine (1975-2011): compétition politique et identités nationales (pp. 135–166). Armand Colin.

Márquez, G. (2014). La formación de los gobiernos autonómicos en Galicia. In J. M. Reniú (ed.), Los gobiernos de coalición de las Comunidades Autónomas (pp. 229–288). Atelier.

Rivera, J. M. (2003). Comportamento electoral e sistema de partidos en Galicia. In J. M. Rivera (ed.), Os partidos políticos en Galicia (pp. 368–427). Xerais.

Rivera, J. M., Lagares, N., Castro, A., & Diz, I. (1999). Las elecciones autonómicas en Galicia. In M. Alcántara & A. Martínez (eds.), Las Elecciones Autonómicas en España, 1980-1997 (pp. 285–307). Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas (CIS).

Sartori, G. (2005). Partidos y Sistemas de partidos. Marco para un análisis. Alianza editorial.

Notes

- These are the three autonomous communities that obtained approval of their statutes of autonomy during the Second Spanish Republic (1931–1939).

- To the triad formed by Catalonia, Galicia, and the Basque Country—regions that achieved autonomy through the designated procedure, as defined by the aforementioned article and specified in the second transitional provision of the Spanish Constitution—was later added Andalusia, on the grounds that this fast-track path should be made available to other autonomous communities as well.

- In the first two autonomous elections, in 1981 and 1985, the total number of deputies to be elected was 71. It was only from the 1989 elections onward that this number increased to 75, which remains in effect today.

- Of the 2,699,424 inhabitants in Galicia, according to data from the National Institute of Statistics (INE) as of January 1, 2023, 76.7% (i.e., 2,070,594 inhabitants) are concentrated in the provinces of A Coruña and Pontevedra, compared to 23.29% (628,830 inhabitants) in those of Lugo and Ourense.

- It is worth noting that, although we are referring here to major cities, only three of them have populations exceeding 100,000: A Coruña (247,350 inhabitants), Ourense (104,187), and Vigo (294,910).

- This threshold was modified, among other electoral reforms, in 1992, raising the minimum requirement from 3% to its current level.

- It is also important to note that, beyond these three major parties, during the first two autonomous elections in 1981 and 1985, the party landscape in Galicia was more fragmented, although characterized by a notable presence of right-wing and center-right parties: Alianza Popular (AP), Unión de Centro Democrático (UCD), and Coalición Galega (CG).

- It should be recalled in this regard that the PPdeG is in fact a refounding of the former Alianza Popular, which makes it possible to assert that the Partido Popular has been a constant presence throughout the entire period of Galician autonomy.

- This tripartite government, composed of the PSdeG, CG, and the Galician Nationalist Party – Galician Party, resulted from a motion of no confidence presented by the socialist candidate Fernando González Laxe against the government then led by Gerardo Fernández Albor (AP). Although he later stood as a candidate in the 1989 autonomous elections—obtaining excellent results for his party—these proved insufficient to secure his appointment as president of the Xunta de Galicia, as the absolute majority was won by Manuel Fraga (PPdeG).

- Among the factors that help explain the hegemonic role of this party, two elements deserve particular attention: first, the capacity of its territorial organisation to maintain a presence in every polling station, despite the high demographic dispersion of the region; and second, the strength of its party apparatus, with a membership base twice the size of that of the other two main parties combined.

- In the first three elections—in 1981, 1985, and 1989—the PPdeG had not yet participated under its current name, but other right- and center-right parties were present: Unión de Centro Democrático, Coalición Galega (CG), and Alianza Popular (AP), the latter being the most voted. AP, which was later reconstituted as the PPdeG, dominated Galician politics until 1989 (Rivera et al., 1999).

- Lagares (2024) notes in this regard “the complexity of left-wing Galician nationalism, with a Galician Nationalist Bloc (BNG) torn between maximalist strategies that keep it in a minority position electorally, and more moderate shifts that secure it significant support, to the point of making it the second political force.”

- In 2012, two internal factions of the BNG — Encontro Irmandiño (EI) and Máis Galiza (+Galiza) — left the party to propose an alternative for that year’s regional elections. This process gave rise to two new platforms: Anova, emerging from EI, and Compromiso por Galiza (CxG), stemming from +Galiza and other small formations. Ultimately, in the election held on October 21, 2012, the AGE coalition (Alternativa Galega de Esquerda – Galician Left Alternative) became the third-largest force in the Galician Parliament, winning 9 seats and 14% of the vote. However, it did not run again in 2016.

- After its time in the bipartite government, the BNG faced a serious leadership crisis and organizational turmoil (Lagares, Rivera, and Máiz, 2012), until it managed, starting in 2016, to articulate a medium- and long-term political project.

- According to data from the CIS (pre-electoral study no. 3440), Alfonso Rueda was the least well-known and lowest-rated among the three main candidates: Rueda (name recognition 95%, rating 4.39), Pontón (92.5%, rating 5.77), and Besteiro (86.1%, rating 4.84).

- The environmental incident in question occurred when a ship, caught in a storm, lost several containers at sea that were carrying sacks of this plastic material.

- The party’s first electoral campaign, designed and led by Xosé Luis Barreiro Rivas, crystallized in an emblematic slogan “Galego coma ti” (“Galician, like you”), which encapsulated the party’s roadmap, giving it a radically different orientation from that of the national party at the time.

- This decision was made after the latter formation rejected, through an internal vote, the acceptance of the pre-agreement.

citer l'article

Nieves Lagares Díez, María Pereira Lopez, Regional election in Galicia, 18 February 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue