Regional election in Lombardy, 12-13 February 2023

Emanuele Massetti

Associate professor at the University of TrentoIssue

Issue #4Auteurs

Emanuele Massetti

Issue 4, January 2024

Elections in Europe: 2023

Political context, candidates and electoral system

The Lombardy regional elections took place on 12th and 13th February 2023, at the end of the term of office of the President (head of the executive body) and the Council (legislative body) elected in March 2018, and just over four months before the Italian general elections in September 2022. The timing was therefore favourable for the centre-right alliance that had recently won the general election (Improta et al., 2022) and whose new government was still in its ‘honeymoon’ phase with the Italian electorate. Moreover, in the electoral geography of Italian regions, Lombardy is presented as a classic example of a centre-right stronghold, as is Veneto and, to a lesser extent, Sicily (Massetti, 2018; Valbruzzi and Vignati, 2021). From the outset, therefore, the electoral result seemed fairly predictable.

However, three factors seemed to provide a modicum of uncertainty. Firstly, the centre-right presidential candidate, incumbent Attilio Fontana (Lega), despite his long political experience at local and regional levels, had, to say the least, a tarnished public image. The policies put in place to deal with the Covid-19 pandemic, which hit Lombardy hard, were severely criticized from all sides. Mr Fontana was also questioned by the Bergamo public prosecutor’s office about the management of the pandemic in Lombardy. Admittedly, at the start of the pandemic, his image was not improved by an appearance on video, in which he made a fool of himself by trying to wear a face mask, without succeeding. Secondly, the general elections in September 2022 did bring in a centre-right majority, but with major upheavals in the balance of power between the various components: Fratelli d’Italia (FdI), led by Giorgia Meloni, had become by far the largest party in the coalition (and in Italy), while Matteo Salvini’s Lega had seen its electoral weight more than halved. The Lombardy elections were therefore likely to cause considerable tension within the centre-right, with the League fearing that the FdI would overtake it in its own stronghold. It is no coincidence that Fontana’s bid for re-election was challenged by FdI, which was leading the polls and demanding a presidential candidate from its own party. Finally, the fact that the Lombardy elections were held at the same time as those in Lazio, where the centre-right candidate had been chosen by FdI, eased an agreement on the Lega’s candidate, Fontana, in Lombardy. The third potential disrupter of an easy centre-right victory was Letizia Moratti’s bid for the presidency, backed by a new centrist political force, Azione-Italia Viva (Az-IV). She is a historic figure of the Lombard centre-right, having served as mayor of Milan (2006-2011) and vice-president and councillor for social welfare in the outgoing Lombard government. In short, a political figure potentially capable of drawing votes away from Mr. Fontana’s candidacy and therefore indirectly favouring the race of candidate Pierfrancesco Maiorino, supported by the Partito Democratico (PD), of which he is a member, by the Movimento Cinque Stelle (M5S), which in previous elections had stood alone with its own candidate, and by the Alliance of Greens and Leftists (AVS). On the other hand, the candidacy of Mara Ghidorzi, supported by a small left-wing force, the Unione Popolare (UP), represented a possible source of electoral drainage for Maiorino.

It is worth recalling that between the mid-1990s and the early 2000s, a series of reforms profoundly transformed the institutional framework of the Italian regions (with the exception of Alto Adige/Südtirol and Valle d’Aosta), moving them from parliamentary to idiosyncratic super-presidential systems (Musella 2009; Marangoni 2013; De Luca and Rombi 2016; Passarelli, 2013). At the same time, the electoral system has become just as extravagant, linking the election of the Council to that of the President. In short, there are two votes: one for the presidential candidates and one for the party lists. The first vote determines the allocation of the office of the President while, in theory, the second vote should determine the composition of the Council. In reality, party lists are linked to presidential candidates and the allocation of seats is heavily influenced by support for the winning candidate. In fact, the majority of seats (48 out of 90) are allocated to the coalition of parties (or the party) that supports the winning candidate in the presidential contest, while 40 seats are divided between all the opposition parties. In addition, two seats on the Council are reserved for the two candidates who came out on top in the presidential contest, i.e. the President-elect and his deputy. In practice, the vote allocated by the electorate to the various party lists only serves to distribute the 48 seats within the winning candidate’s coalition and the remaining 40 seats between the losing coalitions and the parties that make them up.

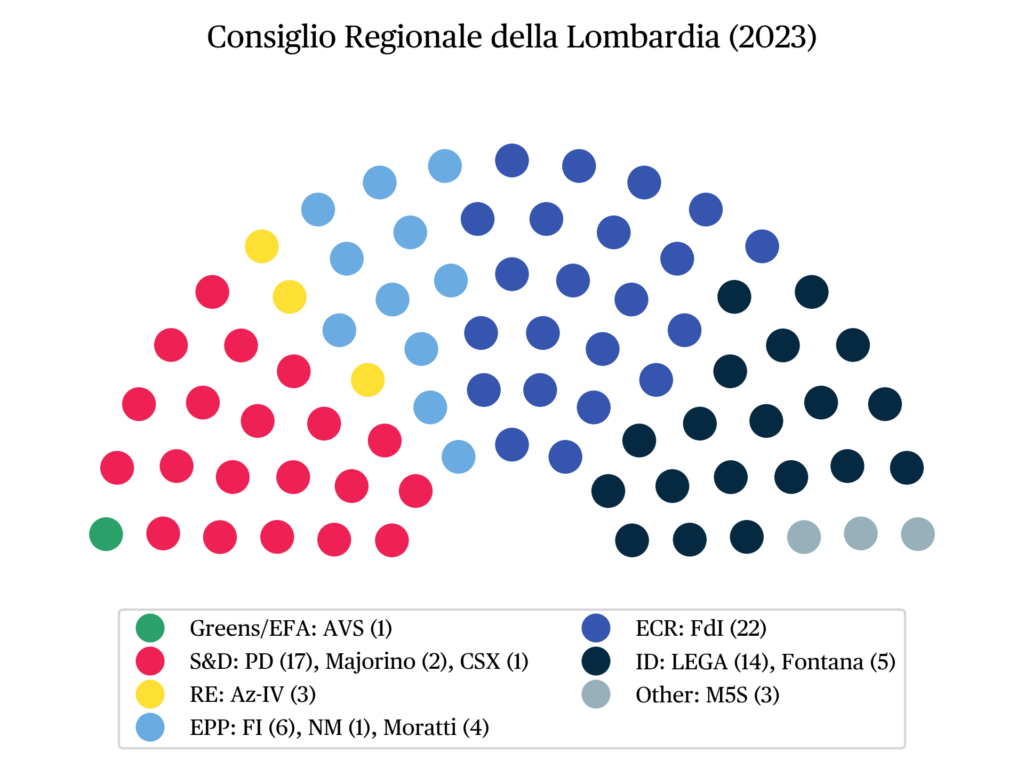

Results

The turnout was 41.6% of voters, 31.5 points lower than in the previous election in 2018 and 23 points higher than the previous abstention record in 2010. The result of the vote, which was almost a foregone conclusion, may certainly have contributed to this drop in turnout. However, the scale of the figure suggests a certain crisis of confidence in political institutions in general, which, as far as the regions are concerned, had already been glaringly apparent in the 2015 elections for ordinary regions (Vampa, 2015; Massetti, 2018), while it seemed partially overcome in the 2020 elections (Vampa, 2020). Turnout was also much lower (-22.2 percentage points) than in the general election four months earlier, which was also a negative record. This comparison confirms the ‘second-order’ nature of regional elections in Italy — especially where ordinary status regions are concerned (Massetti and Sandri, 2013). The results are presented in Figure a, concerning the competition for the presidency of the region, and Figure b, concerning the votes attributed to the various coalitions and electoral lists. As expected, the election resulted in a clear victory for Fontana and the centre-right coalition.

| Candidate | Party | Coalition | Votes (thousands) | Diff. 2018 (thousands) | Votes (%) | Diff. 2018 (pp) |

| Attilio Fontana | Lega | FdI – FI – Lega – Noi Moderati | 1,774.5 | -1,018.9 | 54.7 | +5 |

| Pierfrancesco Maiorino | PD | PD – M5S – AVS | 1,101.5 | -531.9* | 33.9 | +4.8* |

| Letizia Moratti | Independent | Az-IV | 320.3 | – | 9.9 | – |

| Mara Ghidorzi | UP | UP | 49.5 | – | 1.5 | – |

Source: Interior Ministry.

Figure a · Results of the electoral competition between the presidential candidates

| Coalition | Party list | Votes (%) | Diff. 2018 (pp) | Seats | Diff. 2018 |

| Centre-right | FdI | 25.2 | +21.6 | 22 | +19 |

| Lega | 16.5 | -13.1 | 14+1 | -14 | |

| FI | 7.2 | -7.1 | 6 | -8 | |

| Fontana Presidente | 6.2 | +4.7 | 5 | +4 | |

| Noi Moderati | 1.2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 56.3 | +56.35 | 49 | 0 | |

| Centre-left + M5S | PD | 21.8 | +2.6 | 17+1 | -2 |

| M5S | 3.9 | -13.9 | 3 | -10 | |

| Maiorino Presidente | 3.8 | – | 2 | – | |

| AVS | 3.2 | – | 1 | – | |

| Total | 32.7 | – | 24 | – | |

| Centre | Moratti Presidente | 5.3 | – | 4 | – |

| Az-IV | 4.2 | – | 3 | – | |

| Total | 9.5 | – | 7 | – | |

| Radical Left | UV | 1.4 | – | 0 | – |

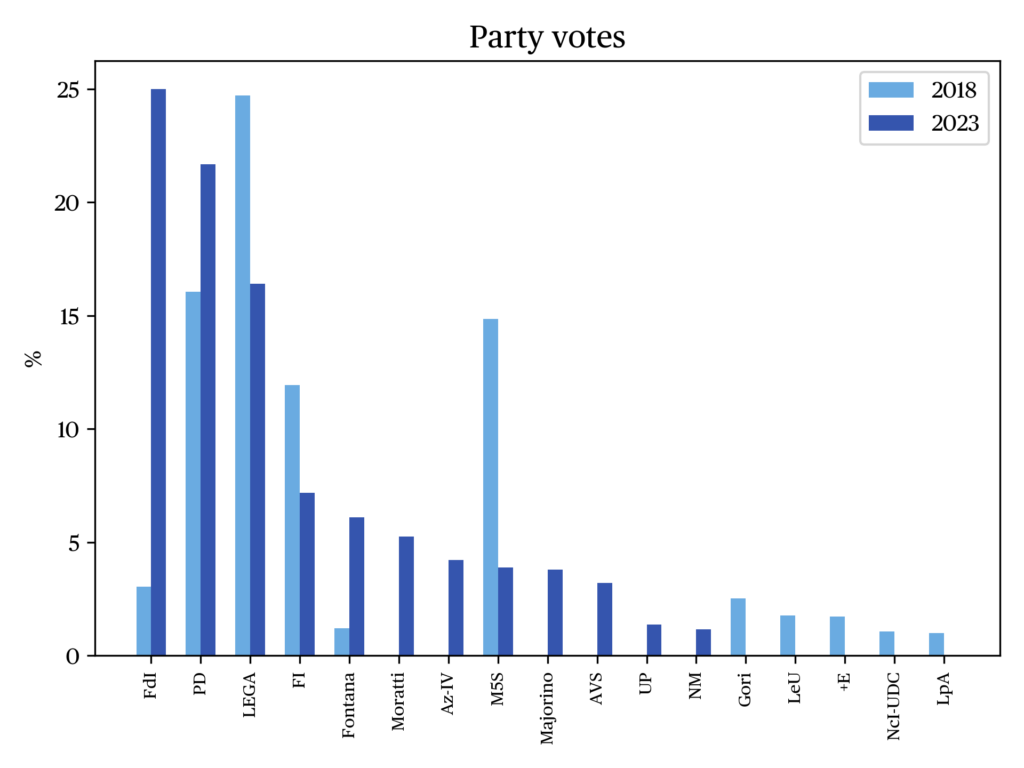

Figure b · Results of the electoral competition between coalitions and lists for the Regional Council

Despite the criticism levelled at him during the previous term, particularly regarding his handling of the pandemic, the Lega candidate came out on top with a significantly higher percentage of the vote (+5) than in 2018, and with his own electoral list — Fontana Presidente — performing better (+4.7 pp) than in 2018. That said, it should be noted that the President-elect lost more than a million votes in absolute terms compared to the previous election.

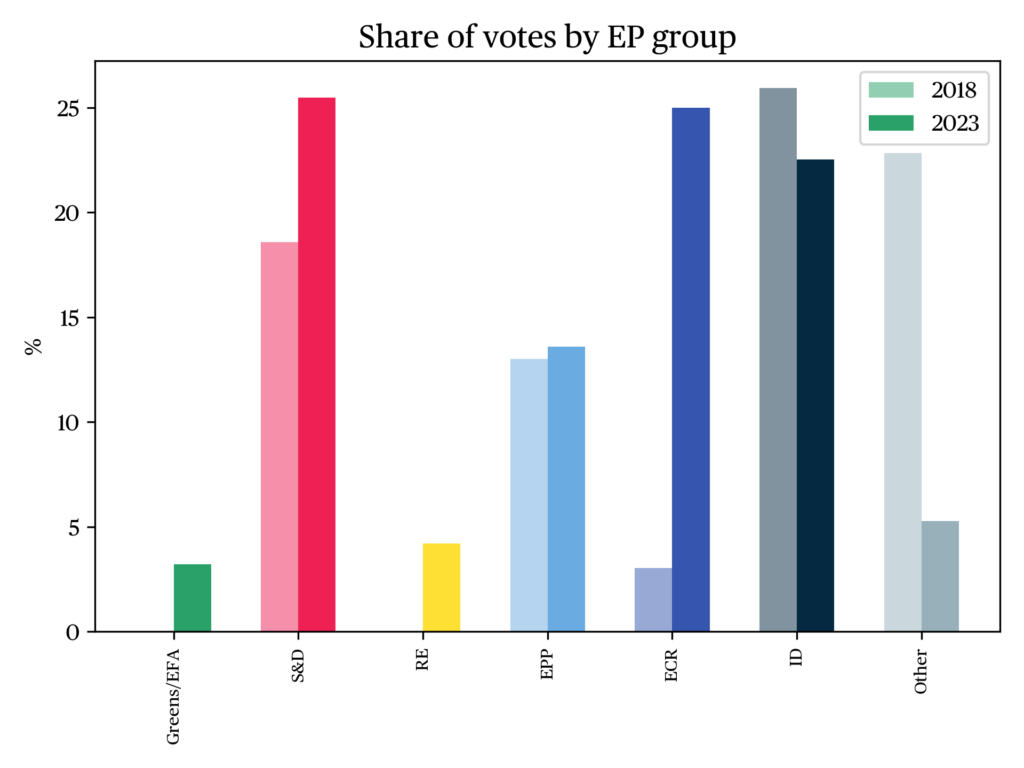

A significant aspect of this electoral competition was the return of political bipolarity. The sum of the vote percentages of the first two candidates was 88.6% – and that of the first two coalitions 89% – in stark contrast to the ordinary regions in 2015 (Tronconi, 2015; Bolgherini and Ghrimaldi, 2017), but in line with the results in 2020 (Vampa, 2021). The third pole (centrist) did not even obtain 10% of the vote. In previous elections, when the third pole was represented by the M5S, the sum of the vote percentages of the first two candidates was 78.7%. Letizia Moratti’s candidacy did not therefore represent a major challenge for the centre-right or a blow to bipolarity, since the second-place candidate, Maiorino (PD), obtained a higher percentage of votes (+4.8) than that obtained by the centre-left candidate in the 2018 elections.

At the same time, the centre-left coalition remains uncompetitive in Lombardy, despite the good performance of the PD (+2.6) and despite the fact that the latter has also allied itself with the M5S. The latter is confirmed as a political force that performs poorly at the regional level (compared to the national level) but, particularly from 2018 onwards, is much more competitive in the southern regions than in northern Italy (Cersosimo and Viesti, 2022). Moreover, it cannot be ruled out that the alliance with the PD had a negative impact on the M5S’s results.

The most interesting part of the results concerns the competition within the centre-right, between the FdI, the Lega and the FI. From this point of view, the elections were a real earthquake, even if it was announced. Forza Italia halved its electoral weight and became the third force in the coalition. The confrontation between FdI and Lega saw the party of the Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni, win clearly, increasing its electoral weight (in percentage terms) sixfold. On the other hand, even counting the votes of the Fontana Presidente list, the League suffered a significant decline and is now the second largest force in the coalition, clearly separated from the FdI.

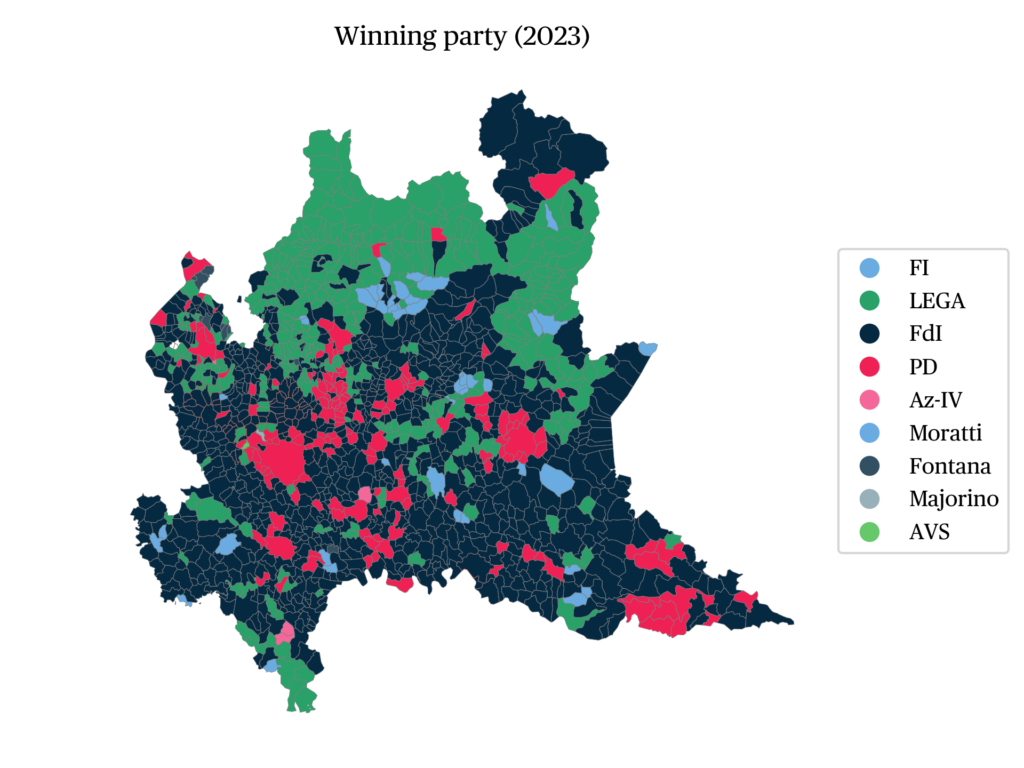

As regards the territoriality of the vote, the relevance of the classic divide — in technical terms (Lipset and Rokkan, 1967) — between the major urban centres on the one hand, and small towns and rural areas on the other, was confirmed. Maiorino won not only in Milan, but also in Brescia, Mantua and even Bergamo. The PD came out on top in Milan, Bergamo, Brescia, Lecco, Lodi, Mantua, Pavia, Sondrio and Varese. On the other hand, if we take into account the small towns outside the metropolitan areas, Fontana won in all the provinces. Finally, as far as internal competition within the centre-right is concerned, the FdI overtook the League in practically all the most important urban centres and in all the provinces, with the exception of Como and Sondrio.

Conclusions

The regional elections in Lombardy produced no major surprises. Lombardy was confirmed as an impregnable bastion of the centre-right, with the incumbent presidential candidate, Fontana (Lega), winning a clear nomination for a second term, despite the criticism he received for his handling of the pandemic emergency and the collapse in turnout. The decision by the PD and the M5S to run as a united front did not prove particularly successful in the Lombardy context, especially for the M5S. On the other hand, the hypothesis that an alliance between the PD and Az-IV — alongside a solo candidacy (or with the UV) of the M5S — would have subtracted more votes from the centre-right is not only devoid of empirical foundation, but also incompatible with a historical trend in Italian electoral behaviour, confirmed at the last general election (Mannoni and Angelucci, 2022), which shows a weak shift in votes between the centre-right and the centre-left. The vote confirms an increasingly obvious gap between the political preferences of large urban centres, clearly in favour of the DP, and those of small towns and rural areas, where the centre-right is largely dominant. The competition between the FdI and the Lega saw the former win in all urban centres and in almost all provinces.

The data

References

Bolgherini, S. & Grimaldi, S. (2017a). Critical election and a new party system: Italy after the 2015 regional election. Regional and Federal Studies, 27(4): 583-505.

Cersosimo, D. & Viesti, G. (2022). Voto da abbandono: L’egemonia del M5S nel Mezzogiorno nel 2018. In Fumagalli, C. and V. Ottonelli (eds.), Votare o no. La pratica democratica del voto, tra diritto individuale e scelta collettiva. Milano: Feltrinelli.

De Luca, M. & Rombi, S. (eds.) (2016). Selezionare i Presidenti. Le primarie regionali in Italia. Novi Ligure: Edizioni Epoké.

Il Fatto Quotidiano (2023, 1 March). Chiusa l’inchiesta di Bergamo sulla gestione della prima ondata Covid: indagati Conte, Speranza, Fontana, Gallera. Il leader M5s: “Tranquillo di fronte al Paese”. Online.

Mannoni, E. & Angelucci, D. (2022). I flussi elettorali tra politiche 2018 e 2022: Lega e M5S alimentano FdI. Centro Italiano Studi Elettorai (CISE). Online.

Marangoni, F. (2013). Organizzazione delle assemblee e processo legislativo. In Vasallo, S. (ed.), Il divario incolmabile (pp. 127-153). Bologna: Il Mulino.

Massetti, E. (2018). Regional Elections in Italy (2012–15): Low Turnout, Tri-polar Competition and Democratic Party’s (Multi-level) Dominance. Regional & Federal Studies, 28 (3): 325–351.

Massetti, E. & Sandri, G. (2014). Neither first nor second order: The 2013 regional and local elections. In Fusaro, C. & A. Kreppel (eds.), Italian Politics: Still Waiting the Transformation. New York: Berghahn Books.

Massetti, E. & Sandri, G. (2013). Italy: Between Growing Incongruence and Region-Specific Dynamics. In Dandoy, R. & A. H. Schakel (eds.), Regional and National Elections in Western Europe: Territoriality of the Vote in Thirteen Countries. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

Musella, F. (2009). Governi monocratici. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Passarelli, G. (2013). La presidenzializzione della politica regionale. In Vasallo, S. (ed.), Il divario incolmabile (pp. 155-190). Bologna: Il Mulino.

Quotidiano Sanità (2023, 25 July). Covid. Tribunale dei ministri archivia inchiesta su Bergamo contro Attilio Fontana e membri del Cts. Online.

Tronconi, F. (2015). Bye-Bye Bipolarism: The 2015 Regional Elections and the New Shape of Regional Party Systems in Italy. South European Society and Politics, 20(4): 553-571.

Vampa, D. (2021). The 2020 regional elections in Italy: sub-national politics in the year of the pandemic. Contemporary Italian Politics, 13(2): 166-180.

Vampa, D. (2015). The 2015 Regional Election in Italy: Fragmentation and Crisis of Subnational Representative Democracy. Regional and Federal Studies, 25(4).

citer l'article

Emanuele Massetti, Regional election in Lombardy, 12-13 February 2023, Jun 2024,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue