Regional election in Madeira, 24 September 2023

Teresa Ruel

Assistant Professor at the University of LisbonIssue

Issue #5Auteurs

Teresa Ruel

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

Introduction

This electoral report focuses on the latest regional elections held in Madeira on 24 September.

Eleven parties and two pre-electoral coalitions — Somos Madeira and the CDU — competed for seats in the regional parliament.

There were high expectations around this competition, related, among others, with the electoral performance of the incumbent parties in the region (PSD and CDS); the potential vote share losses of the main opposition party (PS); and the Chega party’s prospects of entering the regional legislature.

In Madeira, the same political party (PSD) has been in power for 47 consecutive years since democratization (1976). After the latest regional election in Madeira (2019), the PSD needed to form a coalition with the CDS/PP (Popular Party), putting an end to a series of single-party governments that had ruled the region since 1976.

In the 2023 regional election, the vote share for the government parties declined and turnout decreased slightly.

The institutional framework of the Madeiran regional polity — electoral and party systems

With the third wave of democratization that started in 1974, Portugal undertook a process of decentralization and/or regionalization (Ruel 2017; 2021). A regional tier of government was established by the 1976 Constitution which assigned to the autonomous regions (Azores and Madeira) regional autonomy and self-government with a system of representation through directly elected parliaments (assembleia legislativa) and regional cabinets (governo regional) with their own civil service and decision-making autonomy over a wide range of policy areas (Ruel 2015; 2018; 2021).

The autonomous regions adopted a system of proportional representation with closed party lists whereby seats are allocated according to the d’Hondt formula. Voting is not compulsory. Madeira’s 47 regional MPs are elected in a single-tier constituency at the regional level. All political parties in Portugal are statewide parties because regionalist or non-statewide parties are not allowed according to the Constitution (51.4, CPR). Nevertheless, state-wide parties do have territorialized party organizations on the islands (Ruel 2018; 2021).

The configuration of party system which emerged in the region in the 1976 election and persisted during the first three decades of democracy (1976–2007) is best characterized as a predominant-party system, with the PSD (Partido Social Democrata — Social Democratic Party, EPP) winning absolute majorities without being subjected to the political alternation rule. Since 2011, however, the Madeiran party system approximates to a multiparty system, with other political parties gaining political representation: PND (Partido Nova Democracia — New Democracy Party), MPT (Movimento Partido da Terra — The Earth Party Movement, RE), PTP (Partido Trabalhista Português — Portuguese Workers Party) and the JPP (Juntos pelo Povo — United for the People, RE) (Ruel, 2015; 2018). As part of the latest cycle of regional elections in Portugal, the 2019 Madeiran election confirmed this trend by putting an end to the PSD’s single-party’ majority 1 (Freire & Ruel, 2023).

Electoral results and Government formation

The campaign was heavily impacted by the incumbent parties’ electoral strategy. The PSD and CDS/PP (EPP) profiled themselves as the only guarantors of political stability after the election, calling voters to give them an absolute majority in parliament and pledging not to further extend the current government coalition to other parties.

Eleven parties and two pre-electoral coalitions competed for the 47 seats in the regional parliament in the 2023 Madeiran election. About 253,000 voters went to the polls. Turnout was 53,35%, 2,5 percentage points less than in the previous election. The absence of alternative voting options – early and mobile voting — might have negatively affected voter participation.

The center-right ruling parties (PSD — Partido Social Democrata and CDS/PP — Centro Democrático e Social/Partido Popular) formed a pre-electoral coalition — Somos Madeira — which asserted and underlined their ideological identification with the electorate and the terms of the governing strategy to the region that started in 2019.

Since 2011, the PSD has been registering vote share losses in every election. However, they were still able to secure a majority of votes and seats in the regional parliament until 2015. In the 2019 regional election, the PSD lost its seat majority, and the party needed to form a coalition with the CDS/PP (Popular Party) to govern. Thus, following the 2019 regional election in Madeira major changes took place, which confirmed the losses experienced by the incumbent since 2011 (Ruel, 2015). The replacement of the historic leader of the PSD Alberto João Jardim Madeira and his resignation from the regional cabinet before the 2015 regional election, after 39 uninterrupted years of incumbency, likely further fragilized the party, which suffered continued vote share losses in the aftermath.

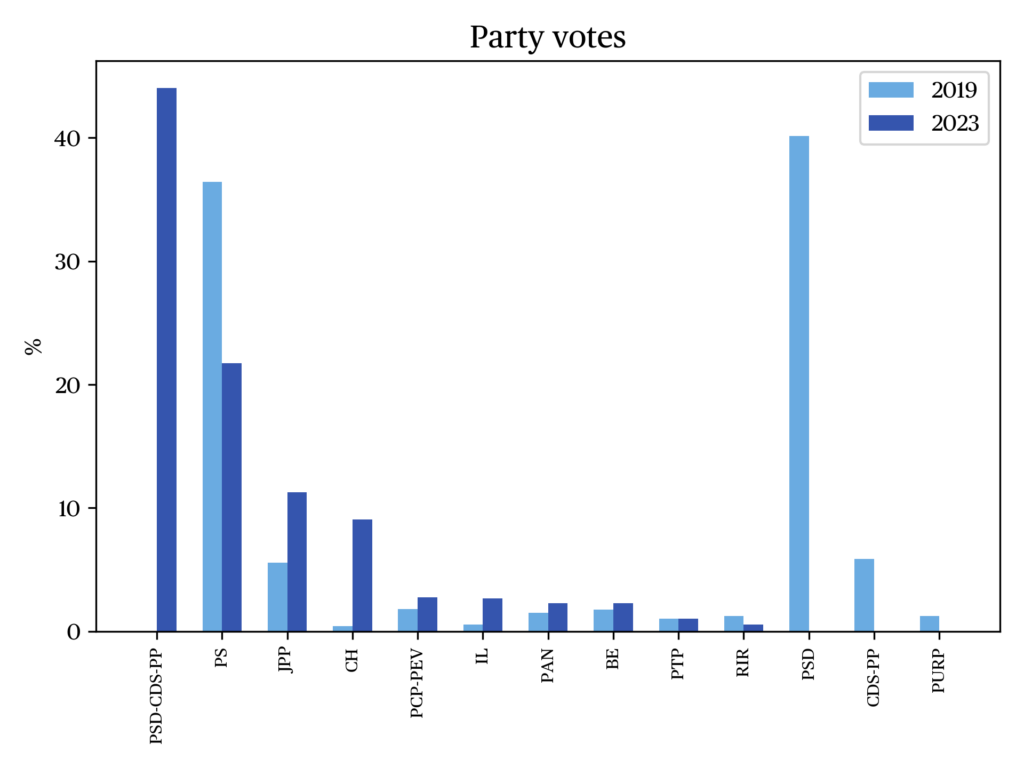

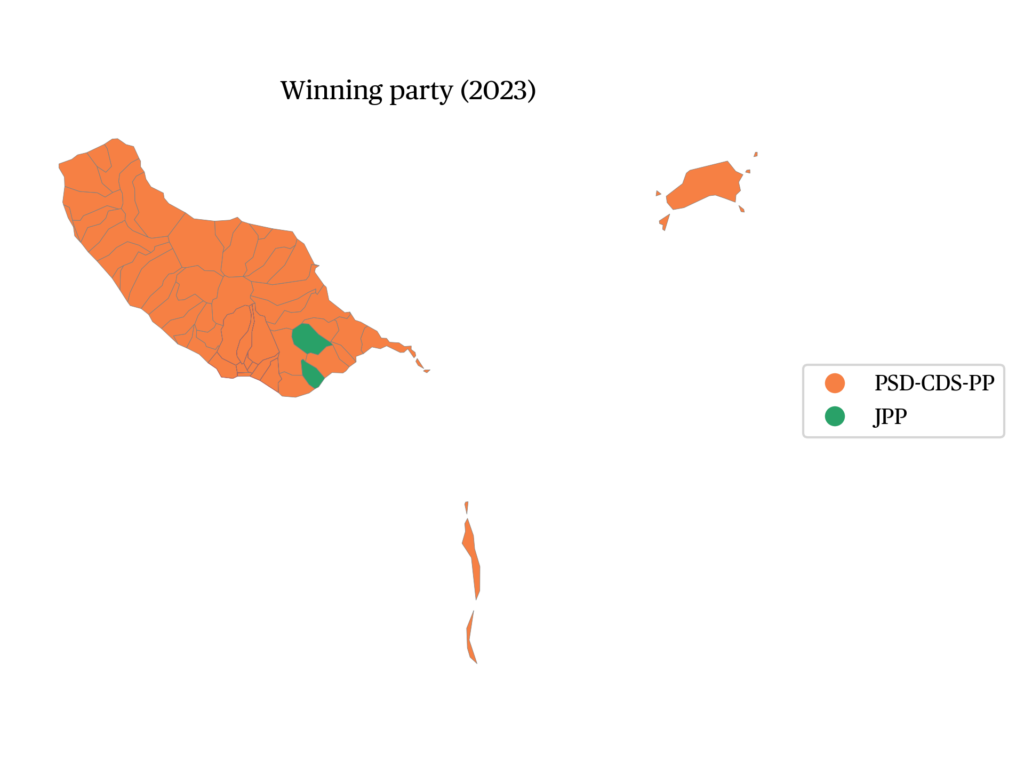

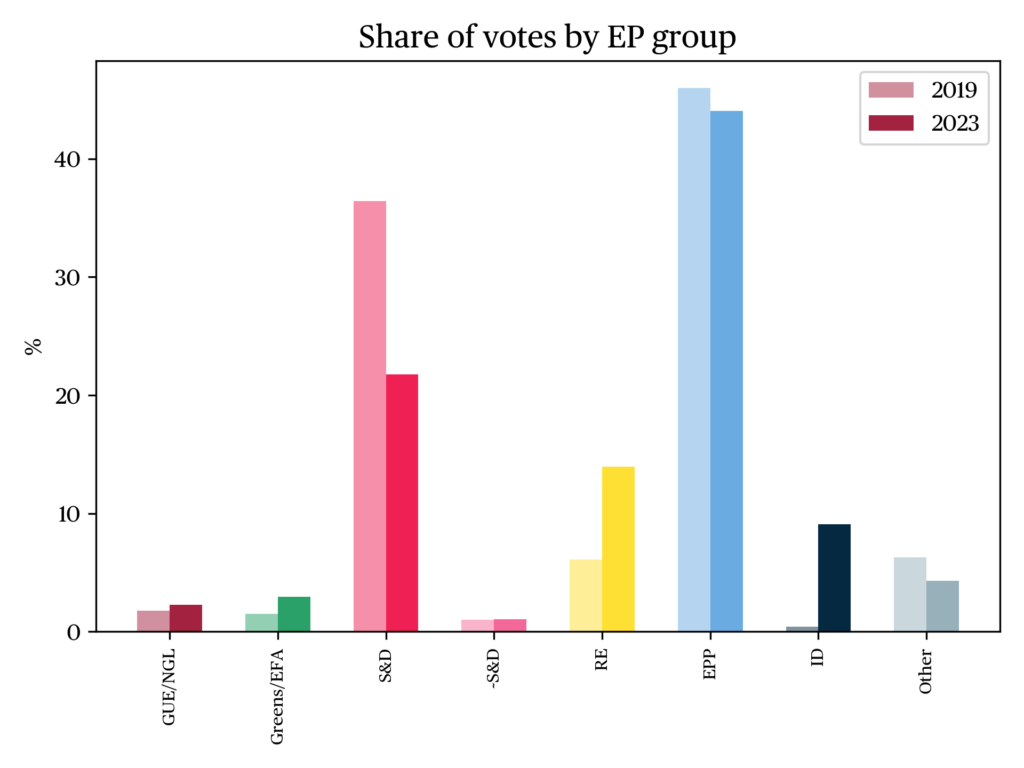

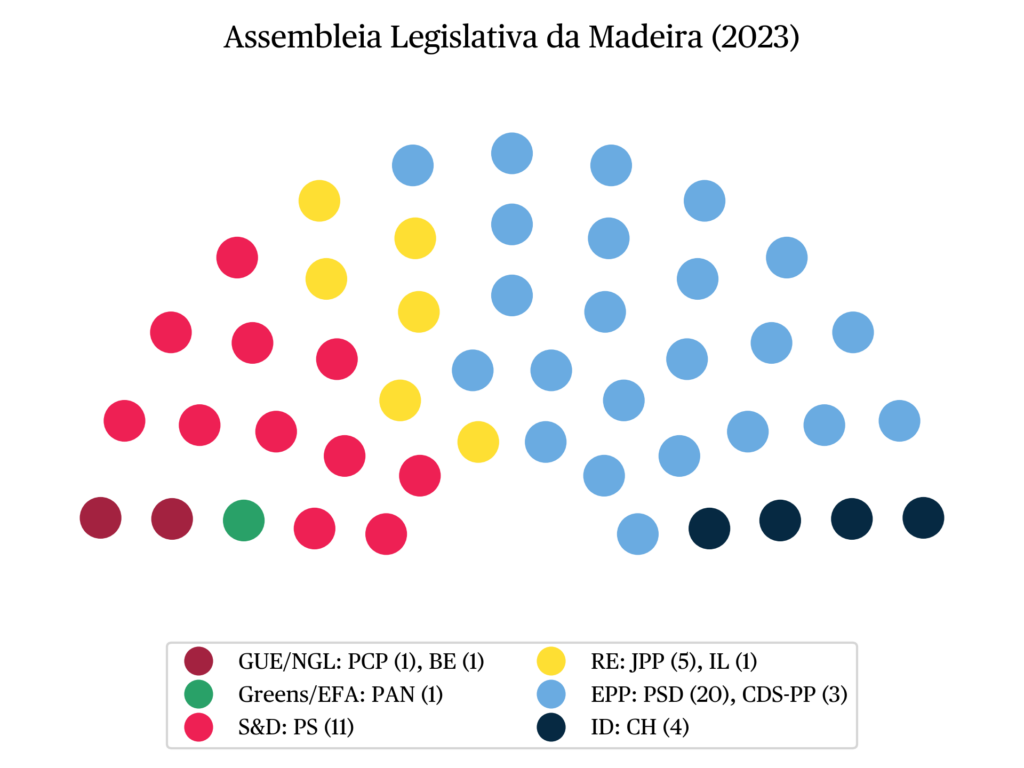

The results of the 2023 regional election show a loss of votes for to the ruling parties which received 44,3% of the votes and obtained 23 MPs in the regional assembly, one seat less than in the previous election (2019). As a result, both parties have come short of a seat majority in the regional assembly.

The losses of the two member parties of the incumbent coalition are difficult to assess individually. However, the combined vote share of the two parties (Somos Madeira — PSD and CDS/PP) was fewer than the sum of the vote share of the two parties in the previous election (2019).

The second-largest party, the Socialist Party (PS, Partido Socialista, S&D) registered a significant breakthrough in the 2019 election, in which it obtained its best electoral performance in the history of regional democracy in Madeira, receiving 36% of the votes and 19 seats. In the 2023 election, the Socialists won 21,89% of the votes and 11 deputies.

Juntos pelo Povo (JPP — United for the People) elected 5 MPs with 11,3% of the vote. The party recovered from the losses registered in 2019 and topped their 2015 result (10,3%).

The Left Bloc (BE — Bloco de Esquerda, GUE/NGL), which had lost parliamentary representation in the 2019 regional election, returned to the regional parliament. The Democratic Union Coalition (CDU — Coligação Democrática Unitária, GUE/NGL) 2 elected one MP with of the 2,79% of votes, increasing its vote share by + 0.9 percentage point.

The vote share obtained by smaller parties and the entry into parliament of new parties is critical for the Madeiran party system. Two new political parties were elected to the regional parliament in Madeira: Chega (CH, literally ‘Enough’, ID) and the Iniciativa Liberal (IL — ’liberal initiative’, RE) 3 . The populist radical right Chega elected 4 MPs with 13% of vote share and became the fourth party in the regional assembly. Chega’s success can be explained by the popularity of its national leadership and the spillovers from the national to the regional political arena (Freire & Ruel, 2023).

The Liberals obtained 2,7% of the votes and 1 MP.

The leftist Partido Animais e Natureza (PAN, Animalist Party) returned 4 to the regional parliament with 2,3% of votes and 1 mandate. Albeit modest, PAN’s electoral success has allowed it to play a key role in the new legislature. The right-wing coalition Somos Madeira (PSD and CDS/PP) have elected 23 deputies and need one more seat to secure the majority in the assembly, and they will count with the parliamentary support of PAN. PAN accepted to take part of the parliamentary agreement to give salience to the animalist and ecologist agenda in the region. In turn, the PSD and CDS/PP required as trade-off the approval of the regional budget every year during the term of the legislature (Expresso, 2023). On this strand, PAN assumed an important role on the sponsorship of the regional government at the regional assembly, despite the ideological distance and incongruence from the center-right parties.

Discussion

The results of the 2023 Madeiran regional election saw vote share losses for both the incumbent parties (PSD and CDS/PP) and the second-largest party (PS), while smaller (JPP) and new parties (Chega, IL and PAN) gained ground in the region.

Even though that, the center-right parties remain to resonate and accommodate the majority of preferences of the electorate in the Madeiran political system.

The 2023 election was characterized by a further increase in party fragmentation, with 4 more parties obtaining representation in the regional parliament. It also gave rise to a new government model: the incumbent parties (PSD and CDS/PP) needed the parliamentary support of PAN to obtain a parliamentary majority. As a result, the regional cabinet is formed by two right-wing parties supported by a green/leftist party in parliament 5 .

2023 has seen major changes that will have a lasting impact on the Madeiran political landscape. The cycle of single-party governments that had characterized the Madeiran polity since 1976 funding elections was broken in 2019, despite the PSD’s efforts to maintain their dominance as a government party. The 2023 electoral results confirmed the tendency of erosion of the governing parties’ vote shares and introduced a new practice of parliamentary agreements into the Madeiran political landscape. Nevertheless, after 47 years of regional democracy in Madeira, full political alternation has still not taken place.

The data

References

Expresso (2023, 26 September). Madeira: PAN confirma acordo de incidência parlamentar que inclui 10 pontos.

Freire, A. & Ruel, T. (2023). Regional elections in Portugal: Madeira (2019) and the Azores (2020): the two-way spill over between national and regional politics. Regional & Federal Studies.

Ruel, T. (2021). Political Alternation in the Azores, Madeira and the Canary Islands. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ruel, T. (2018). Regional Elections in Portugal, the Azores and Madeira: Persistence of Non-Alternation and Absence of non-Statewide Parties. Regional & Federal Studies 29 (3): 429–440.

Ruel, T. (2017). As regiões autónomas (Açores e Madeira) nos debates parlamentares da Assembleia da República (1975-2015), Colecção Parlamento, Lisbon: Assembleia da República.

Ruel, T. (2015). Madeira Regional Elections 2015: A Polity Tyrannized by Majorities or the End of an Era? Regional & Federal Studies 25 (3): 313–320.

Notes

- Likewise, in the 2020 Azorean regional election, the electoral results brought to an end a long period of single-party dominance (Freire & Ruel, 2023).

- The Democratic Union Coalition (CDU — Coligação Democrática Unitária)is formed by the Communists (PCP — Partido Comunista Português) and the Greens (PEV — Partido Ecologista os Verdes).

- Both parties — Chega (CH) and Iniciativa Liberal (IL) made their appearance on the regional electoral arena in the 2019 election but failed to win a seat at the time.

- PAN elected a regional MP for the first time in the 2007 Madeiran regional election.

- Likewise, the former government in the Azores (2020-2024) was a coalition of right-wing parties — PSD, CDS/PP PPM, a monarchist party — with parliamentary support from Chega and the Liberals. The early election held in Azores on 4th February (2024) re-elected the incumbents which govern in a minority cabinet.

citer l'article

Teresa Ruel, Regional election in Madeira, 24 September 2023, Jun 2024,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue