Regional election in the Azores, 4 February 2024

Teresa Ruel

Assistant Professor at the University of LisbonIssue

Issue #5Auteurs

Teresa Ruel

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

Introduction

In late 2023, early elections to the Azorean parliament were called following the rejection of the regional budget proposal for 2024. This ended the incumbent center-right coalition government ‘s term, one year before the regular end of its mandate. The Portuguese President of the Republic called early elections for 4 February 2024.

The electoral results saw the incumbent majority win the most seats amid increased turnout. However, despite their victory in the ballot box, center-right parties have struggled to deliver the stability promised during the electoral campaign, as government formation proved challenging.

Background to the election

In the last regional election in Azores (2020), the Social-Democratic party (PSD–Partido Social Democrata, EPP) formed a post-election coalition government with the Popular Party (CDS/PP–Centro Democrático Social/Partido Popular, EPP) and the Popular Monarchist Party (PPM–Partido Popular Monárquico). The center-right parties secured formal parliamentary support from the Liberals (IL – Iniciativa Liberal, RE) and the populist radical-right Chegaparty (CH, ID/PfE) for their minority government. The ‘cordon sanitaire’ around Chega was essentially a rhetorical device, voiced during the electoral campaign. Since 2020, regional executive has Chega’ support at the parliament.

The Socialist Party (S&D), despite being the most voted party, was ousted after 24 years of incumbency.

The governmental formula that emerged from the 2020 election was marked by instability and constraints in the regional parliament from the outset. Challenges emerged on two levels.

Firstly, at the institutional level, inter-party conflicts arose in parliament amongst the minority government and the MPs that supported it. Secondly, intra-party tensions also surfaced within the assembly.

The coalition arrangement was constrained by both the COVID-19 pandemic and a fragmented parliament. This became especially evident in the second wave of the pandemic (2021), when the Liberals used their ‘blackmail potential’ to impose some of their policy choices in exchange for approving the regional budget. Overall, the cooperation between the coalition partners and their MPs parliamentary supporters was characterized by persistent institutional deadlocks, with bills being negotiated piece by piece throughout the legislative term.

In addition, the intra-party tensions echoed within the regional assembly. One of the Chega’s MPs withdrew from the party out of dissatisfaction with its national leadership, becoming an independent MP within the parliament. This event further weakened the minority government’s support, although in practice the independent MP voted hand in hand with the minority government. Moreover, the Liberals persisted in their strategy claiming the fulfilment of the coalitional agreement. Within the regional cabinet, various political divergences emerged, particularly on health issues, causing the resignation of the regional health minister.

The challenges of leading a minority government culminated in the rejection of the regional budget proposal in November 2023. The regional premier acknowledged the limitations of governing without a majority and called for an early election, hoping the regional electorate would grant a clear mandate to one side.

The institutional framework

The 57 MPs to the Azorean assembly are elected from ten constituencies: nine corresponding to the nine islands of the archipelago and, since the 2008 regional elections, one compensatory constituency. 1 Until the 2004 regional elections, the Azorean electoral system was characterized as extremely disproportional and unequal (a phenomenon known as malapportionment 2 ), which distorted the ‘value of vote’ (Dahl, 1971). The district magnitude across the nine islands varies from 2 to 20, which means that some parts of the population are heavily over-represented. To address this, a five-seat compensatory electoral constituency was introduced at the time of the 2008 regional election to reduce disproportionality and to introduce some equilibrium between the islands. These five compensatory seats are allocated based on the aggregation of remainder votes from the nine constituencies at the regional level (Ruel, 2018, 2021).

The Azores region traditionally had a two-party system in which, until 2020, the Socialist Party (PS, S&D) was structurally dominant and electorally stronger than the PSD, which remained in opposition for 24 consecutive years under PS governments.

The electoral results

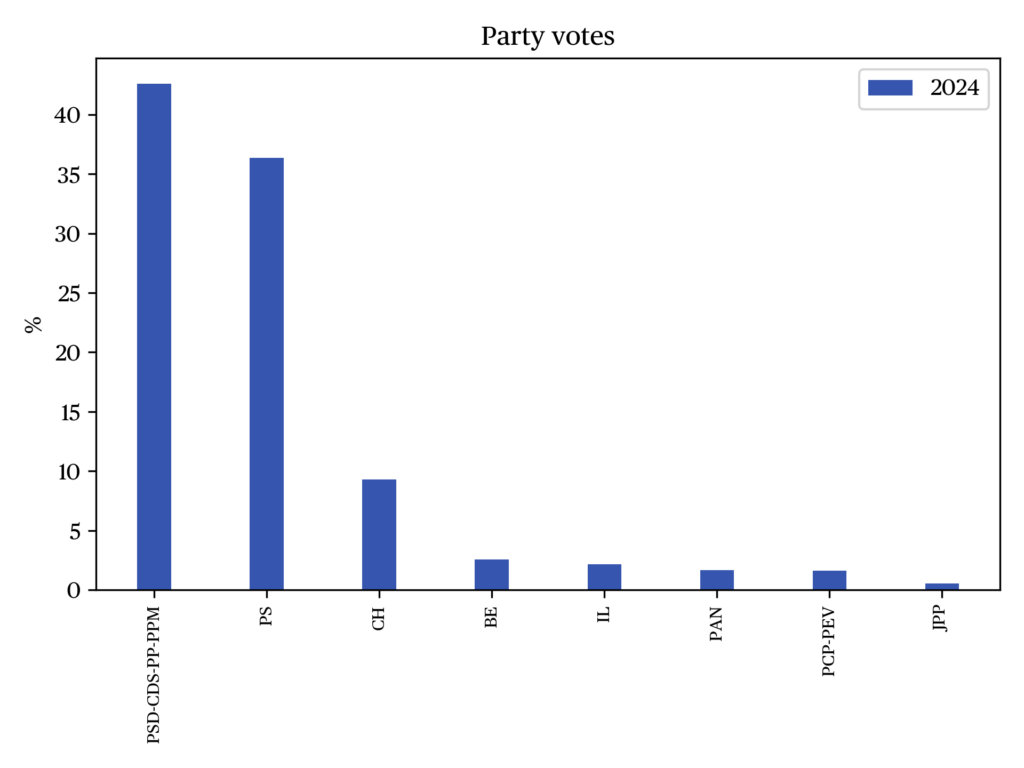

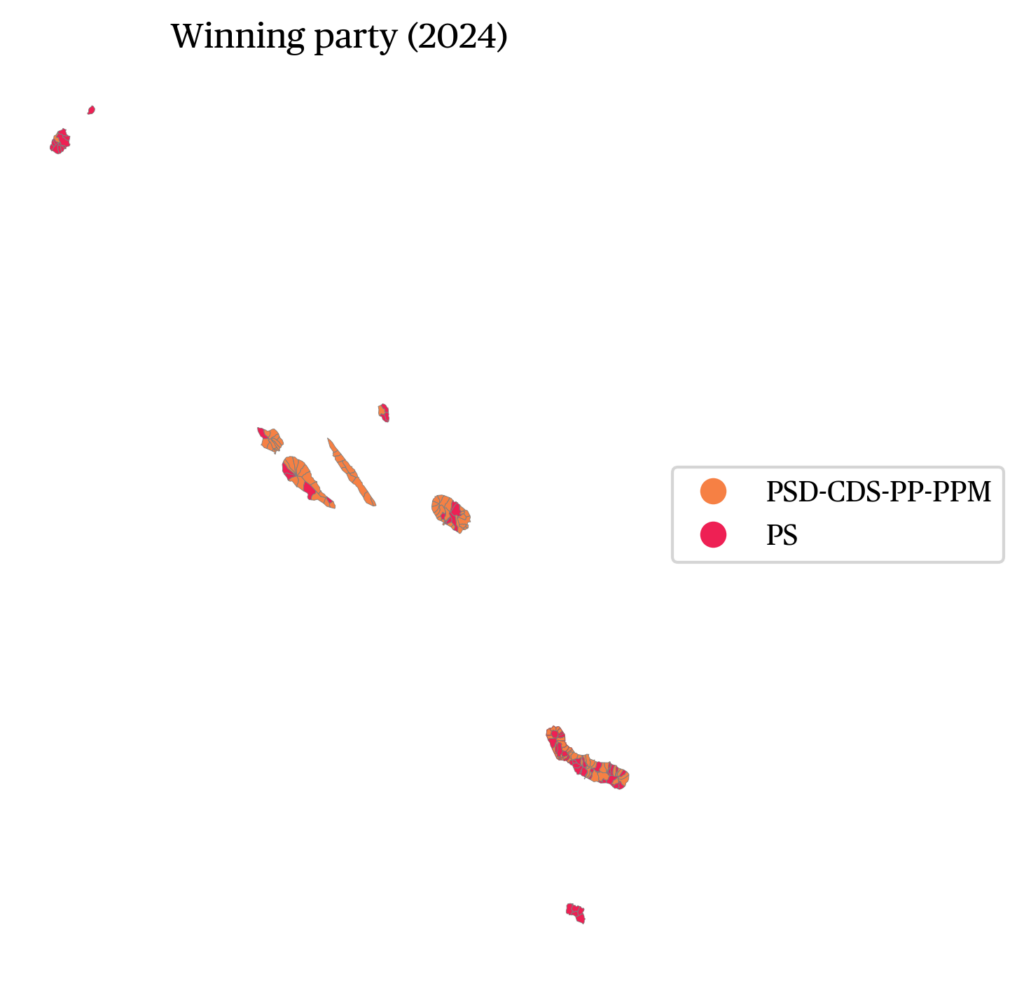

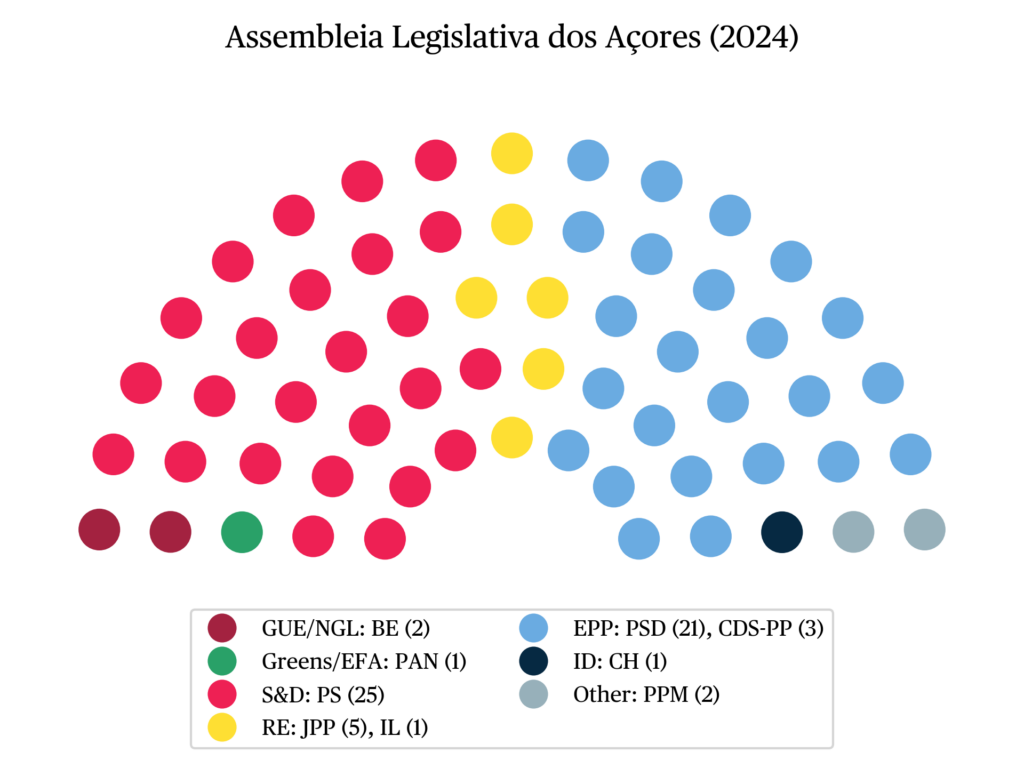

On 4th February 2024, about 230,000 voters went to the polls in Azores. Six of the eight competing parties and three pre-electoral coalitions won seats in the regional parliament. Voter turnout increased by 4.89 percentage points (pp) when compared to the previous election, reaching 50.3%.

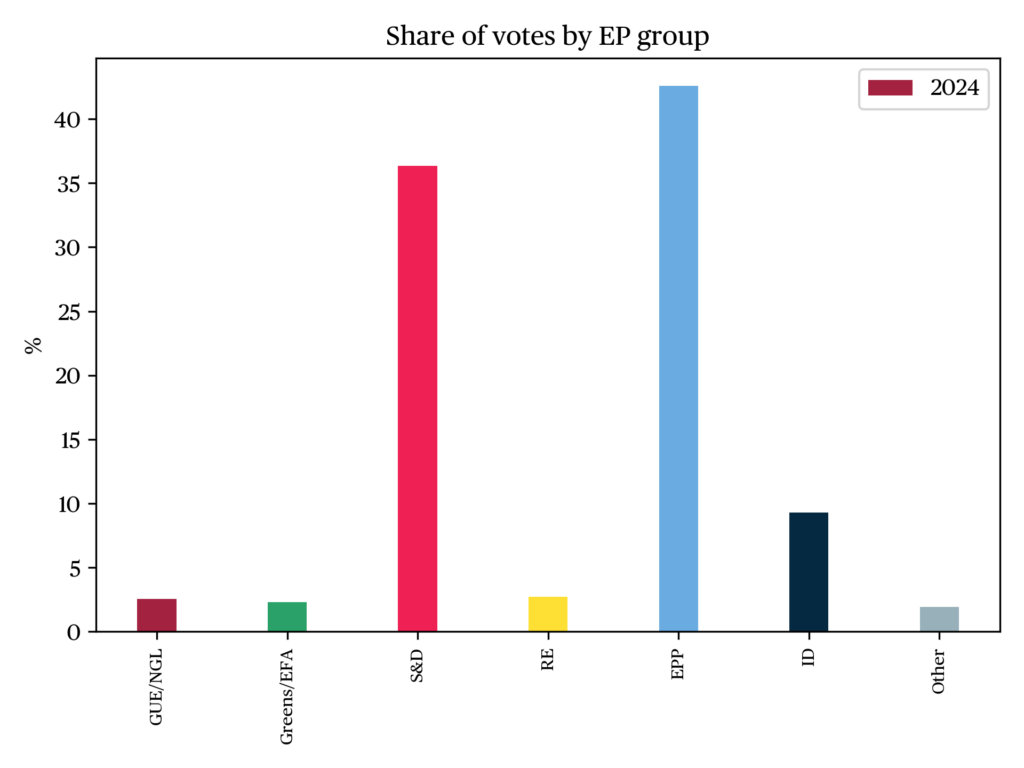

The governing parties (PSD, CDS/PP and PPM) formed a pre-electoral coalition, Unidos pelos Açores, (“United for Azores”) – prioritizing governmental stability and the fulfillment of their electoral programme. This move underscored the challenges faced by the previous coalition government. “Unidos pelos Açores” eventually received 43.56% of the vote, electing 26 MPs – one more than in the previous election in 2020. The coalition would have needed three more seats to secure a majority in the assembly and avoid minority status.

The biggest losses were registered on the left side of the party system. The Socialist party lost in terms of both vote share (-3.47%) and seats (23, -2). The Left Bloc (Bloco de Esquerda, BE, GUE/NGL) saw its vote share decline (- 1.27%) and lost one seat. The Communists ( Partido Comunista Português, CDU, GUE/NGL), despite an increase in its vote share (+ 1,17%), failed to obtain parliamentaryrepresentation for the second consecutive term.

Chega almost doubled its vote share (+ 4.29), electing five MPs (+3). The Liberals and PAN (Pessoas Animais e Natureza – Animalist party, Greens/EFA) elected one deputy each as in the previous election. In the aftermath of the vote, the center-right coalition once again took the helm of the regional government, this time without formal support from other parties in the regional assembly. How governmental stability will be maintained remains unclear.

Discussion

The rejection of the regional budget and 2024 early election showed narrow gains for the EPP incumbents and larger losses for the Socialist party (S&D) and Left Bloc (GUE/NGL). The Communists’ (GUE/NGL) failed to obtain seats in the regional assembly while the Liberals and PAN are still represented with an MP each. The rise of the radical-right Chega party, which registered the strongest electoral gains, led to a doubling of its vote share and number of elected MPs. In terms of parliamentary configuration, the regional assembly is composed of the same parties as in the previous term.

The 2020 election ended the era of single-party governments in the Azores, and the 2024 confirmed this shift. In 2020, the radical right (Chega) formally supported the center-right minority government in the regional parliament. However, cooperation with Chega and the Liberals proved challenging, eventually leading to early elections. In contrast, the 2024 Azorean election highlighted the impact of the radical right surge on party strategies and government formation. Nevertheless, the centerright parties managed to form a government without formal parliamentary agreements, in line with their national strategy of avoiding the radical right as coalition partners.

To sum up, the early election to the Azorean parliament, while leading to the incumbents’ re-election, has not brought the expected government stability. The Azorean coalition government now rules as a minority, without formal parliamentary support.

The data

References

Dahl, R. (1971). Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Freire, A., & Ruel, T. (2023). Regional elections in Portugal: Madeira (2019) and the Azores (2020): the twoway spill over between national and regional politics. Regional & Federal Studies.

Monroe, B. (1994). Disproportionality and Malapportionment: Measuring Electoral Inequity. Electoral Studies, 13, 132–149.

Ruel, T. (2021). Political Alternation in the Azores, Madeira and the Canary Islands. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ruel, T. (2018). Regional Elections in Portugal, the Azores and Madeira: Persistence of Non-Alternation and Absence of non-Statewide Parties. Regional & Federal Studies, 29(3), 429–440.

Notes

- In 2006, the Organic Law 5/2006 was approved by the national parliament, introducing a reform to the Azores’ electoral law that created a compensatory electoral constituency.

- Malapportionment is defined as the discrepancy between the share of legislative seats and the shares of population held by geographical units (Monroe, 1994).

citer l'article

Teresa Ruel, Regional election in the Azores, 4 February 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue