Regional election in the Basque Country, 21 April 2024

Issue

Issue #5Auteurs

Francisco José Llera Ramo , José Manuel León-Ranero

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

Introduction

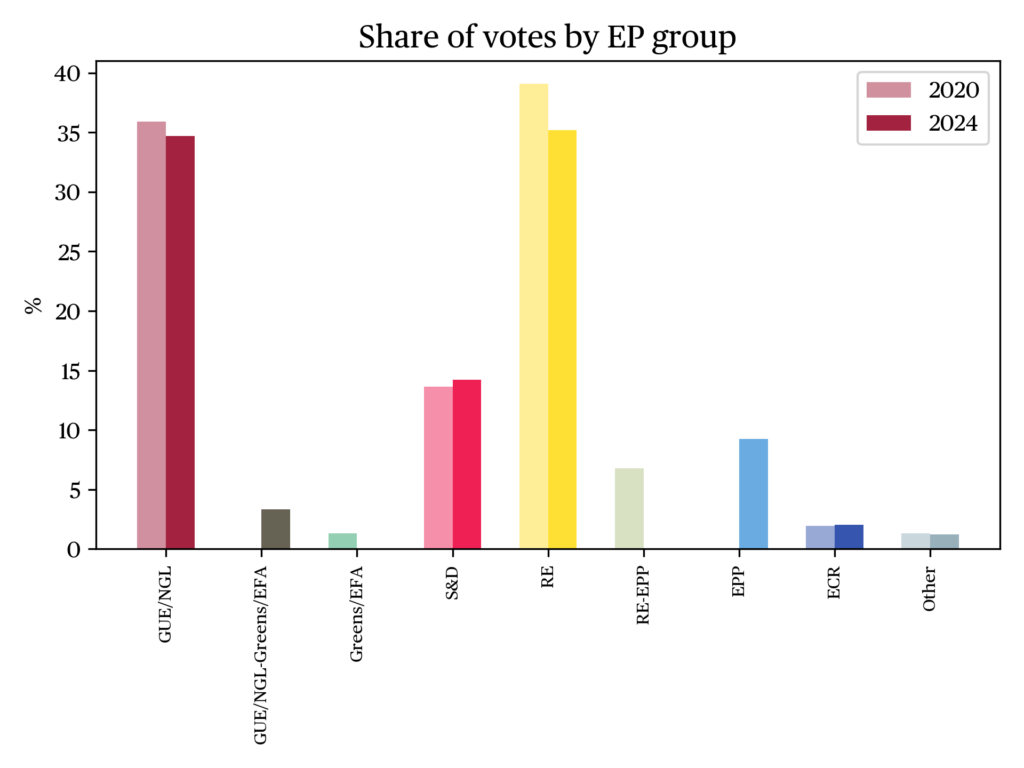

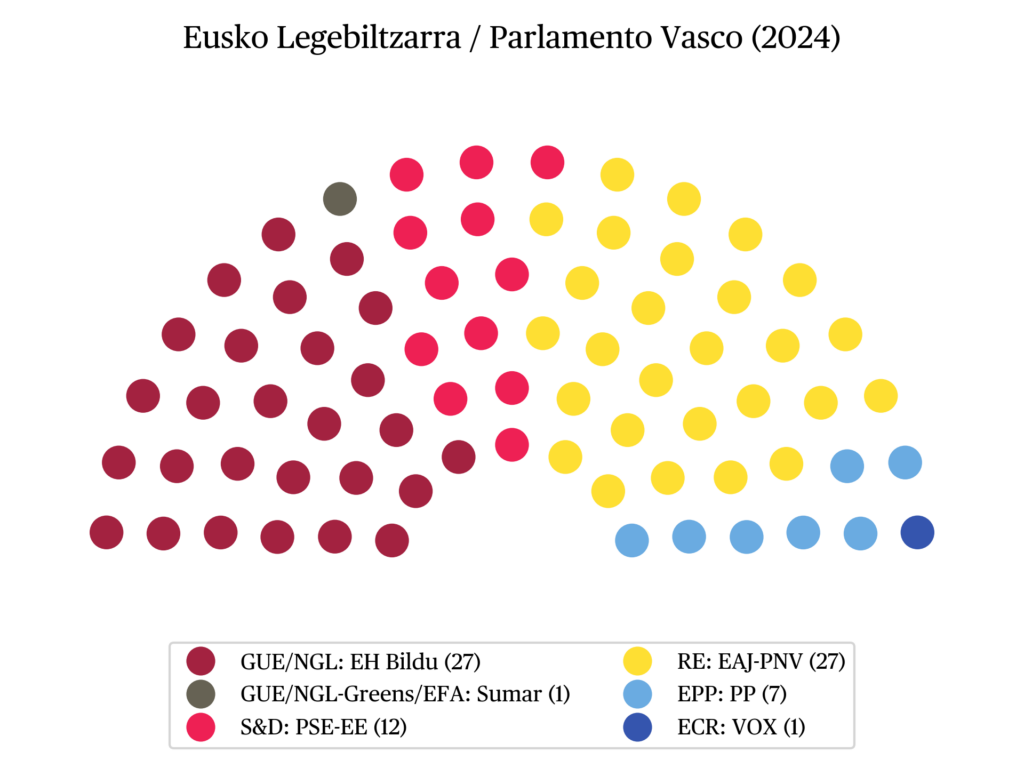

The Basque party system is structured around two main axes of competition: the classical left–right ideological divide common to all Western political systems, and the identity or territorial dimension, often referred to as the center–periphery cleavage. Within this two-dimensional political map, a diverse array of electorally and parliamentary relevant political options have emerged since 1980: five nationalist forces, nearly a dozen autonomist ones, a similar number in the center and right, and about half a dozen on the left (Llera and León-Ranero, 2023). In Basque regional elections, citizens elect 75 representatives, 25 from each of the three provinces (Álava, Guipúzcoa and Vizcaya), regardless of population size. In 2024, arranged from left to right and from nationalist to non-nationalist, the following parties can be identified: on the radical nationalist left, EH Bildu (27 seats); on the non-nationalist left, PSE (12), Podemos (0), and Sumar (1); on the nationalist center-right, PNV (27); and on the non-nationalist center-right and right, PP (7) and Vox (1). Traditionally bolstered by differential abstention which tends to affect the non-nationalist electorate more and by tactical voting in favor of nationalist parties in regional contests, nationalist actors currently dominate Basque politics.

The 2024 Basque regional elections took place within a broader cycle of instability and political realignment initiated by the 2023 local and provincial (foral) elections, followed by the national parliamentary elections later that year, and concluding with the 2024 European elections. These contests, marked by a comprehensive change in leadership across all major parties, signal the end of Íñigo Urkullu’s three-term presidency: the first term (minority, single-party) followed the end of ETA’s terrorist campaign; the second was a minority coalition between the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) and the Socialist Party of the Basque Country–Euskadiko Ezkerra (PSE-EE); and the third secured an absolute majority with the same coalition.

Key to the 2024 elections, which were framed by a return to mixed coalition politics unlike the Catalan case (Llera, 2020), was the parliamentary alliance at the national level between the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE) and the nationalist parties PNV and Euskal Herria Bildu (EHB). Other important issues included post-pandemic voting trends (Llera and Rivera, 2022), public dissatisfaction with health and education services affecting the incumbent coalition (PNV and PSE-EE), and the centrifugal, albeit asymmetric, rise of EHB, at the expense of a PNV that fielded a new candidate, Imanol Pradales, as well as the strengthening of the Basque Popular Party (PP). The contest between Podemos and Sumar and the defense of Vox’s single seat (Llera and León-Ranero, 2024) also shaped the electoral landscape. The election campaign focused on leadership renewal, institutional fatigue from the outgoing government cycle, and increasing ideological polarization contrasted with a decline in identity-based polarization.

A second-order election marked by high competition between PNV and EHB

After record-low turnout in the 2020 regional elections, held during the COVID-19 pandemic, participation in 2024 rose to 60%, an increase of 9.2%, though still below the historical average of 64.2%. This relatively uniform turnout across the three Basque provinces confirm the second-order nature of regional elections (Schakel, 2015; Golder et al., 2017) and the differential mobilization that tends to benefit nationalist parties (Llera, 2016c).

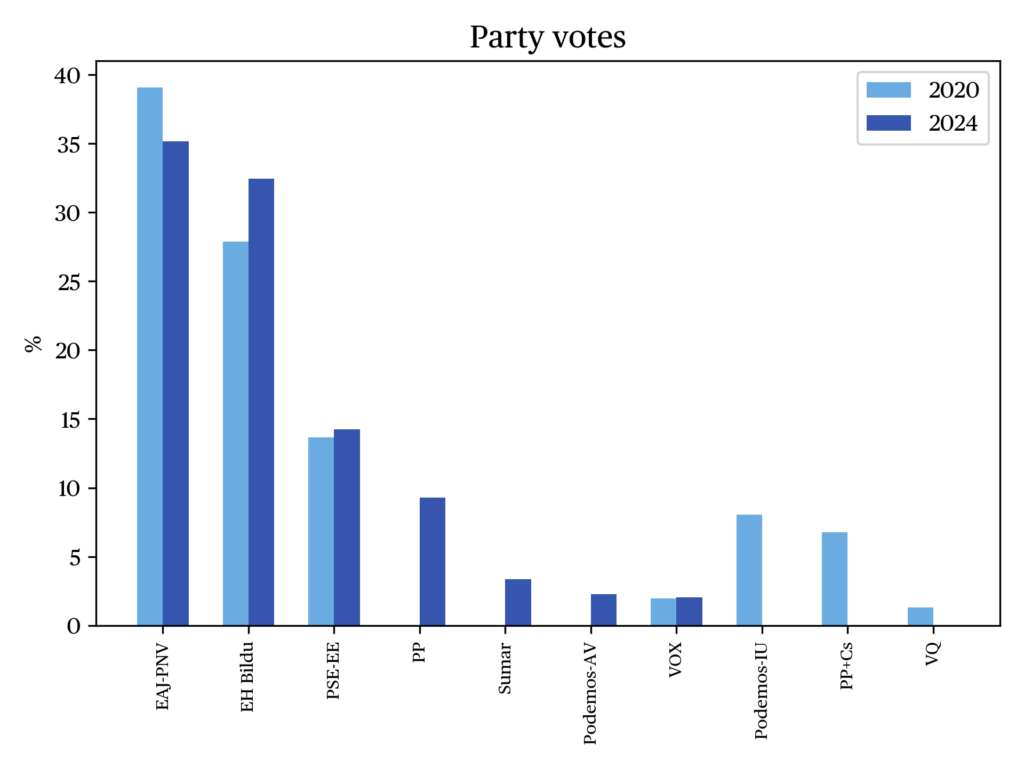

The primary question in the 2024 regional election was the outcome of the PNV–EHB duel (see “the data”), centered on the potential overtaking of PNV by EHB after the latter’s surge as a radical nationalist left coalition. The result was a Pyrrhic victory for a declining PNV (-3.9%), whose campaign emphasized renewal and moderation in contrast to the “radicalization” and uncertainty associated with its opponent. EHB, the radical Basque left party, presented a youthful and pragmatic image, less radical and less tied to its past connections with terrorism, positioning itself as a useful vehicle for the Indignados Movement that had migrated to Podemos since 2015. This allowed EHB to make significant electoral gains (+4.5%) and tie PNV in seat count.

The governing partner, PSE-EE, achieved its goals by retaining mobilized autonomist voters, increasing its vote share (+0.6%), and gaining two additional seats by positioning itself as a centrist and pivotal force in future coalitions. The Basque PP, adopting a centrist tone and criticizing the radicalization of the PSOE–PNV–EHB coalition in Madrid, failed to significantly cut into the utility vote for PNV and PSE-EE but did record its first electoral gain in two decades (+2.5%). Among minor parties, Vox retained its Álava seat and made modest gains (+0.1%) through an anti-nationalist discourse and criticism of PP’s ambiguity. Meanwhile, the plurinational left suffered from its fragmentation into Podemos and Sumar, and from vote concentration in favor of EHB.

An analysis of electoral loyalty and voter transfers reveals varied patterns of stability and volatility (see Figure a), with EHB (94.3%), PP (85.6%), and Vox (83.9%) showing the most stable electorates compared to 2020. In contrast, Podemos suffered a dramatic erosion in its voter base (32.1%), followed by PSE-EE (73.3%) and PNV (77.9%).

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on CIS Post-Election Survey No. 3459 on the 2024 Basque Regional Elections.

Net volatility, estimated at around 164,000 voters, primarily benefited EHB, which absorbed substantial numbers of former Podemos voters and, to a lesser extent, those from PNV and abstention. While PNV retained most of its base and recaptured votes from PSE-EE and new voters, PSE-EE also attracted support from former PNV and Podemos voters, abstainers, and first-time voters. The PP consolidated its gains through high loyalty and cross-party attraction from PNV and socialist voters, while Vox drew support from the PP and younger voters. Sumar emerged as a partial successor to Podemos but lacked full absorptive capacity. Overall, vote transfers illustrate a reshaped Basque electoral arena, where EHB now resembles a catch-all leftist party, juxtaposed against the fragmentation of the non-nationalist bloc and a stable conservative vote.

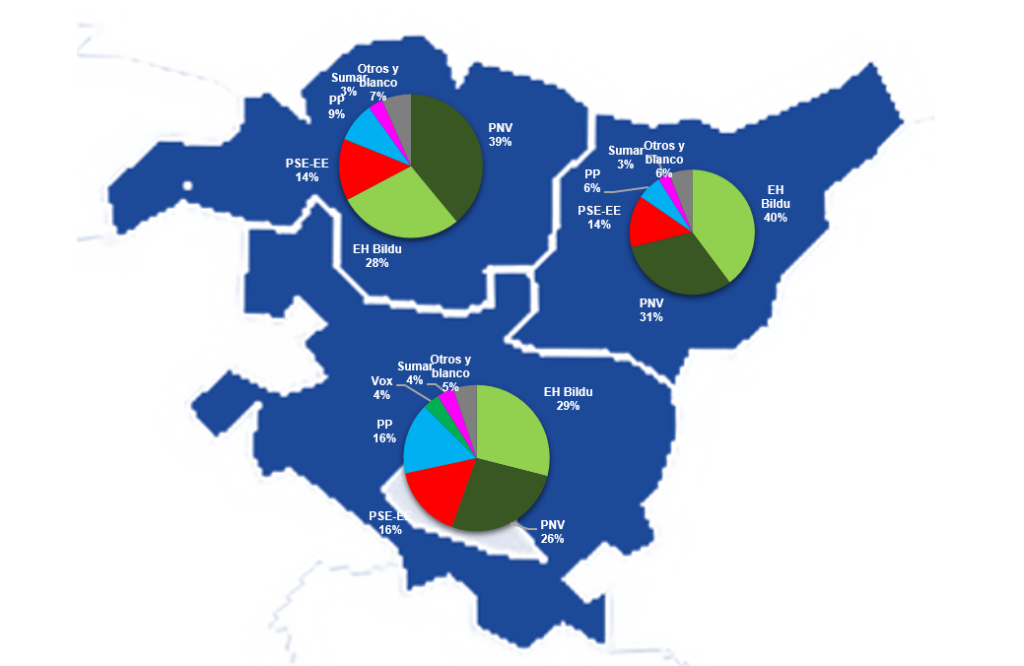

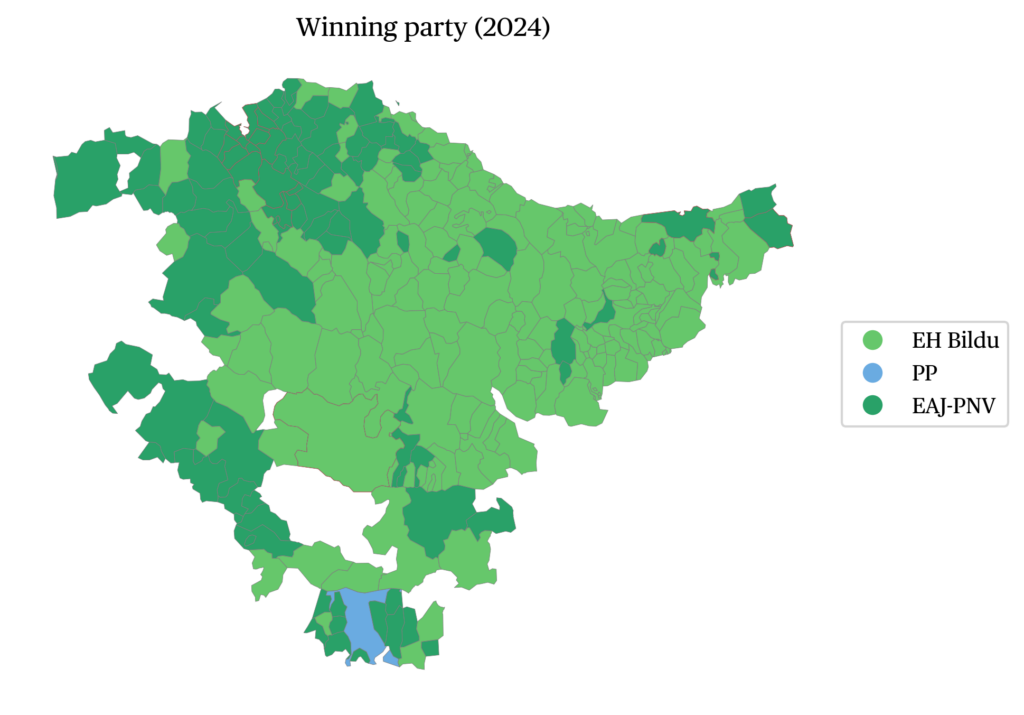

The PNV–EHB rivalry was most evident in the erosion of PNV’s territorial dominance (see Figure b), with PNV winning only in Bizkaia and finishing second in Álava and Gipuzkoa, where EHB prevailed. EHB’s electoral gains were concentrated in smaller interior and coastal towns, especially in Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia, as well as in metropolitan and industrial areas (see “the data”), among both nationalist and left-leaning constituencies. Particularly significant was its breakthrough in Álava and its victory in Vitoria.

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on data from the Provincial Electoral Boards.

Percentages calculated on valid votes.

A stable governability scenario amid nationalist hegemony and lower identity polarization

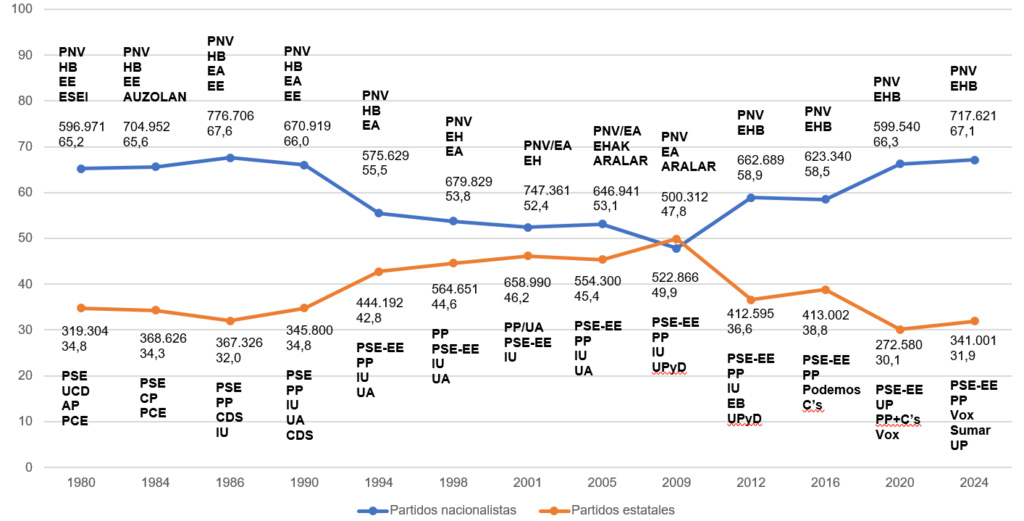

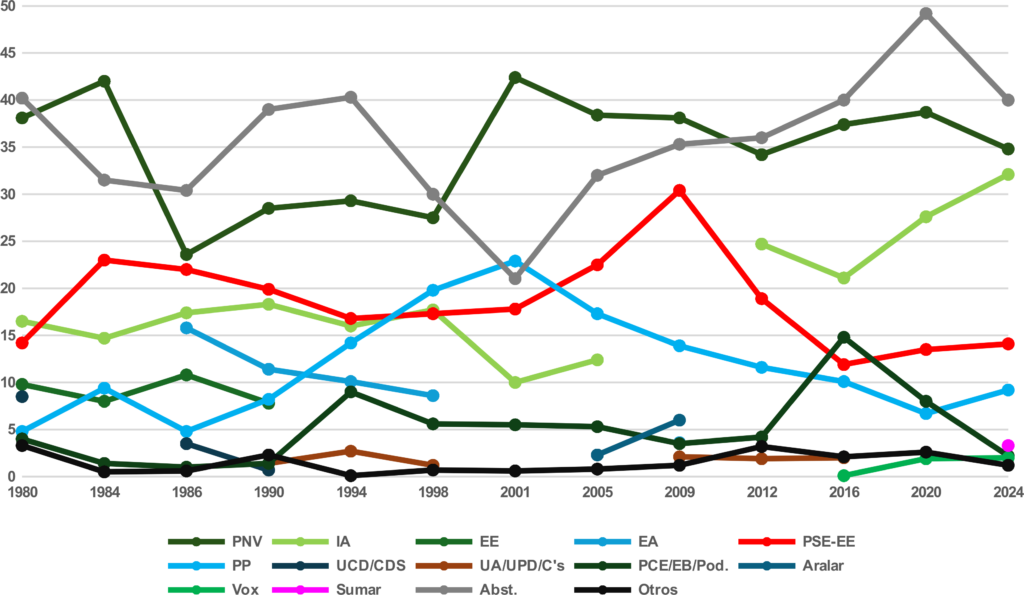

The intense PNV–EHB competition resulted in a record nationalist performance (around 717,000 votes), accounting for 67.2% of valid votes and 72% of parliamentary seats—close to the historical high of 1986 (see Figure c). Basque nationalism, whether left- or right-leaning, foralist or pro-independence, has thus consolidated its hegemonic position through control of regional, provincial, and municipal institutions and via its strategic engagement with the PSOE–Sumar national government. This has left non-nationalist parties fragmented, polarized, and at historically low levels of electoral support.

Figure c · Evolution of nationalist and statewide vote in Basque elections, 1980–2024

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on data from the Provincial Electoral Boards.

PNV’s relative decline, traditionally buffered by a blend of nationalist pragmatism and centrist appeal that attracted moderate and regionalist utility voters, benefited EHB. The latter, through strategic partnerships with the PSOE in Madrid and Navarre (Llera, 2016a), attracted not only its traditional pro-independence base but also protest voters, youth, and radical social movements.

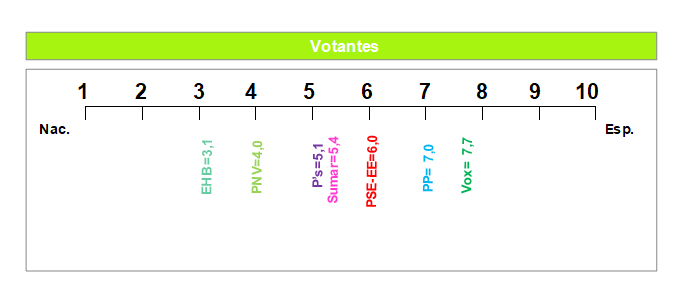

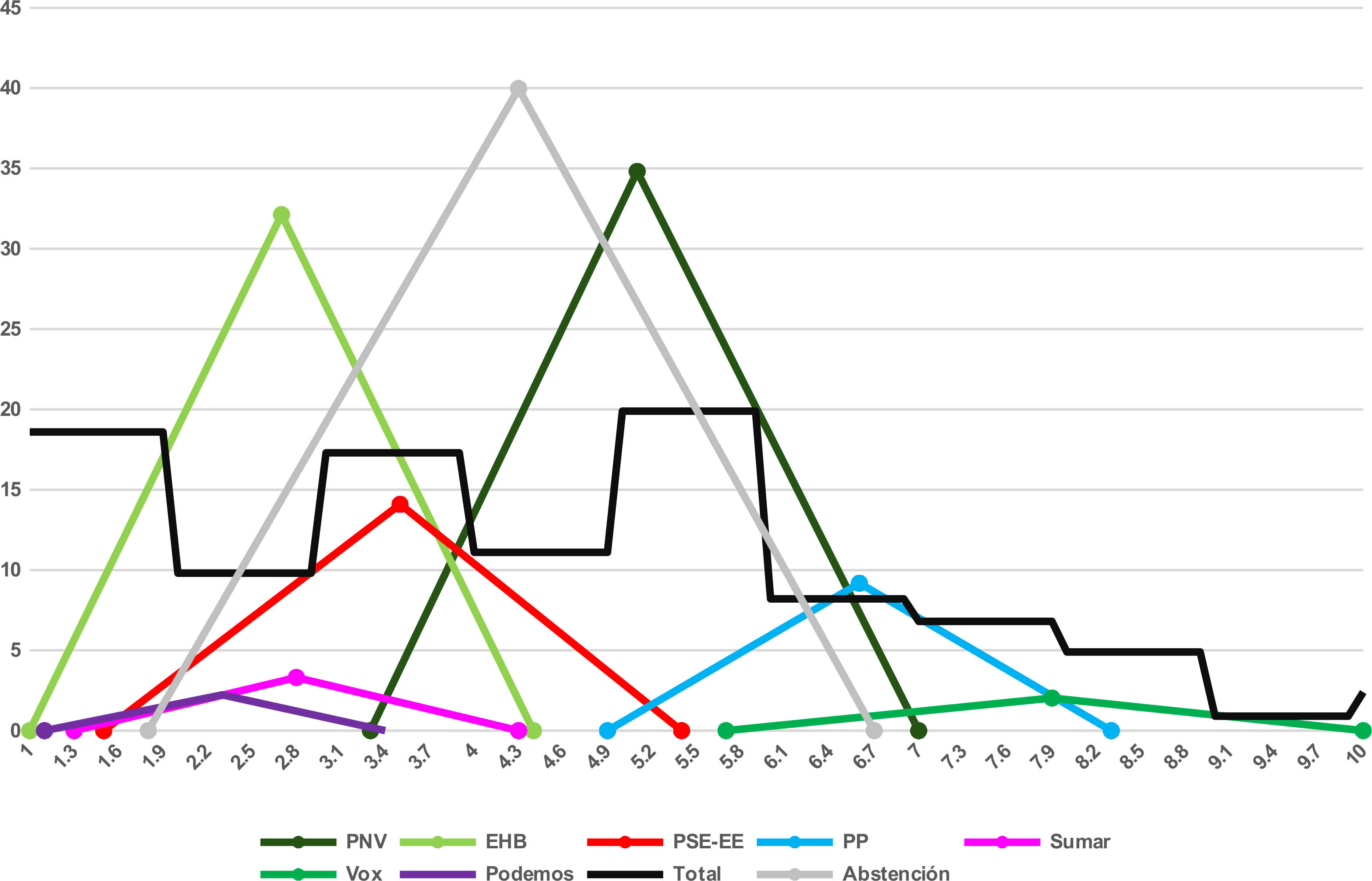

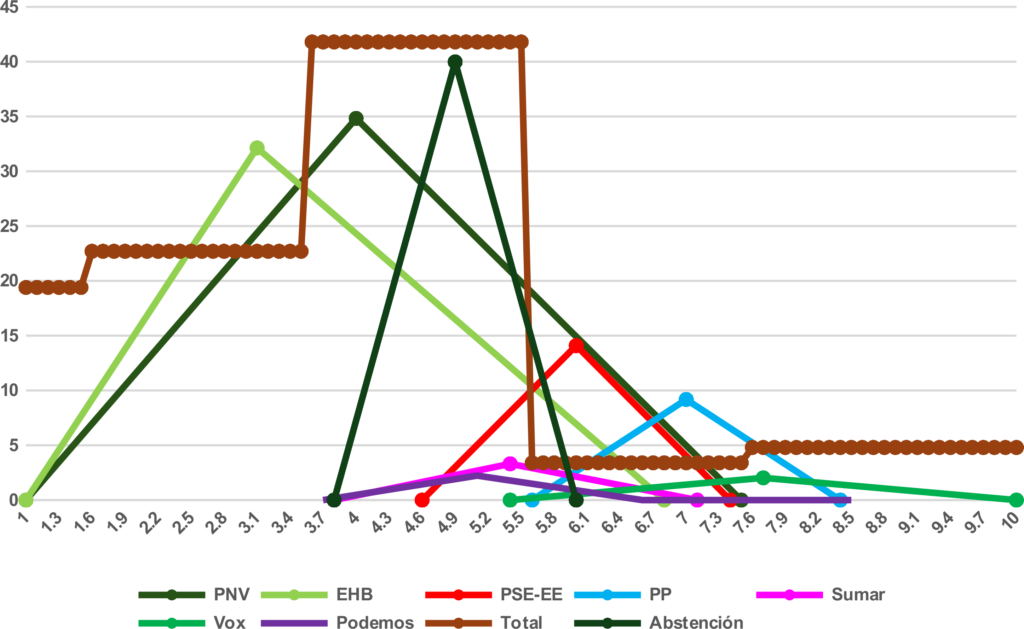

These electoral shifts can also be explained by a reconfiguration of both ideological and identity-based polarization. While ideological distance between extreme parties (Podemos–Sumar vs. Vox) slightly increased by 0.2%, overall ideological polarization (0.62) remained similar to 2020, with heightened tension on the far left due to centripetal competition on the center-right. This ideological moderation and the leftward shift of the electorate (see Figures d and e) coexist with a new, highly effective bloc-based polarizing narrative promoted from Madrid 1 . Under this discourse, the ruling PSOE–nationalist coalition constructs a cordon sanitaire around the PP (and its agreements with Vox), portraying it as either anti-system or politically pariah (“the right and the far right”).

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on CIS Post-Election Survey No. 3459 on the 2024 Basque Regional Elections.

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on CIS Post-Election Survey No. 3459 on the 2024 Basque Regional Elections.

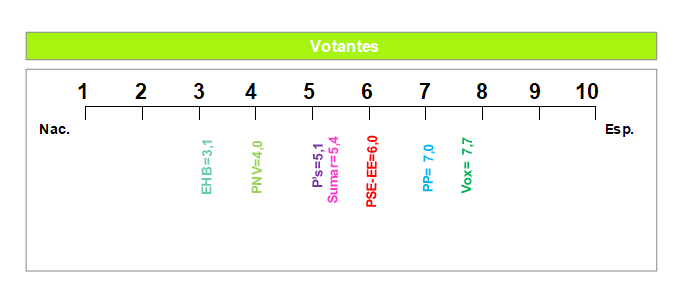

However, more significant change has occurred in the identity dimension (Basque vs. Spanish sentiment). While the Basque electorate remains inclined toward Basque identity, the average identity score among Vox voters (7.7) shifted slightly (-0.3 points) toward the center without affecting its vote share. EHB’s average (3.1) moved +0.7 points toward autonomism, coinciding with its electoral surge. For the first time, the ideological distance between extremes narrowed significantly (-1.0 point), bringing the identity-based polarization index (0.51) below that of ideological polarization in a regional election (see Figures f and g).

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on CIS Post-Election Survey No. 3459 on the 2024 Basque Regional Elections and Euskobarómetro Study 2019-05.

Figure g · Average identity positioning of Basque parties on the Basque/Spanish axis based on voter self-placement in the 2024 regional elections

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on CIS Post-Election Survey No. 3459 on the 2024 Basque Regional Elections and Euskobarómetro Study 2019-05.

Despite these shifts, the Basque political system remains largely stable in terms of party structure and governance patterns (Harrop and Miller, 1987), with some emerging dynamics worth noting (Llera and León-Ranero, 2023). The number of parliamentary parties remains unchanged (six), although system fragmentation has decreased 2 . Were it not for the disproportionate provincial representation system, neither Sumar nor Vox would have secured seats, effectively reducing parliamentary representation to four parties. PNV remains the leading party, though competitiveness has peaked (a 2.7-point valid vote margin) with a seat tie with EHB, the main challenger. The governing coalition (PNV and PSE-EE) retains its absolute majority (39 seats) 3 , allowing it to renew its agreement (Llera, 2016b). Total aggregate volatility (Pedersen, 1983; Bartolini, 1986) increased slightly (Vt= 15,2) 4 , above the regional average (13.9), though mostly within the same ideological family, especially in the identity dimension. Notably, an alternative majority government is now viable, with EHB and PSE-EE jointly holding 39 seats—and already governing together at the national level.

| Basque Country | ||||||

| 2020 | 2024 | |||||

| Votes | Seats | Votes | Seats | |||

| (%) | T | (%) | (%) | T | (%) | |

| PNV | 38.7 | 31 | 41.3 | 34.8 | 27 | 36 |

| EHB | 27.6 | 21 | 28 | 32.1 | 27 | 36 |

| PSE-EE | 13.5 | 10 | 13.3 | 14.1 | 12 | 16 |

| PP | 6.7 | 6 | 8 | 9.2 | 7 | 9.3 |

| Vox | 1.9 | 1 | 1.3 | 2 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Podemos | 8 | 6 | 8 | 2.2 | – | – |

| Sumar | – | – | – | 3.3 | 1 | 1.3 |

Source: Provincial Electoral Boards of the Basque country.

Note: In 2020, PP ran in coalition with Ciudadanos.

Conclusions

The 2024 Basque regional elections must be analyzed within the longitudinal context of 44 years of Basque autonomy (Llera, 2016c) and a in light of ETA’s cessation of terrorist activity ten years ago (Jauregui, 1981; Domínguez, 1998; Elorza et al., 2000; Benegas, 2007; Eguiguren and Rodríguez, 2010; Leonisio, Molina, and Muro, 2021). Since the beginning, nationalist options have held an advantage (see Figure i), due to two electoral behavior patterns (Liñeira and Muñoz, 2014): differential abstention more prevalent among autonomist voters due to lower interest, and tactical or swing voting between nationalist and non-nationalist options depending on whether elections were regional or general.

Figure i · Evolution of Voting in Basque Regional Elections, 1980–2024

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on data from the Department of Security of the Basque Government.

Note: PNV ran in coalition with EA in 2001; PP in coalition with UA in 2001 and with Ciudadanos in 2020.

In sum, the 2024 elections reaffirm the waning dominance of the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV), sustained thus far by a historically effective blend of political moderation, administrative competence, institutional entrenchment, and strategic adaptability in times of crisis. Yet this predominance appears increasingly subject to temporal limits. While there is a discernible appetite for political alternation, it remains hampered by unresolved ethical tensions surrounding the legacy of terrorism and the incomplete moral closure of that chapter in Basque history.

The continued strength and competitiveness of the nationalist bloc unfold within a moderate and conservative society that places high value on effective governance and institutional continuity—particularly within the intricacies of the Basque foral system. However, this hegemony now confronts a horizon of growing uncertainty, especially among younger generations, shaped by the convergence of multiple structural crises: demographic decline, migratory pressures, deindustrialization, and emerging cleavages around well-being.

The data

Notes

- It all began in Barcelona with the Tinell Pact in 2003, continued in Valencia with the Botànic Pact in 2015, and was further consolidated with the motion of no confidence against Mr. Rajoy in June 2018, which led to a negative coalition government headed by Pedro Sánchez—subsequently extended through the coalition governments of 2020 and 2023.

- The Statute of Autonomy of the Basque Country, in line with its foralist inspiration, guarantees equal parliamentary representation for the three historical or foral territories, regardless of their respective demographic weight. Under Basque electoral law, each province is allocated 25 seats.

- An absolute majority in the Basque Parliament is set at 38 seats. Although the Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) lost four seats, the Socialist Party of the Basque Country–Euskadiko Ezkerra (PSE-EE) gained two, allowing the coalition to renew its majority government.

- This outcome reflects a shift of at least 164,000 votes across party lines.

citer l'article

Francisco José Llera Ramo, José Manuel León-Ranero, Regional election in the Basque Country, 21 April 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue