Regional election in Thuringia, 1 September 2024

François Hublet

Editor-in-chief, BLUEIssue

Issue #5Auteurs

François Hublet

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

Introduction

The second least populous of the eastern German states, Thuringia has gained a reputation as a laboratory for the rise of right-wing extremism and its consequences on regional political governance. Since the emergence of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) as a key political player in the mid-2010s, the region has seen the far-right party become the fourth-largest (2014) and later second-largest (2019) political party in its regional parliament, the Landtag. While until 2024 the level of AfD support in Thuringia was not always substantially higher than in Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, or Brandenburg, the combination of the AfD’s rise with the larger voter base of left-wing Linke in the region has challenged traditional coalition-making practices as early as 2014 (Opelland, 2015, 2020). In addition, the profile of the AfD’s regional leader and founder, Björn Höcke, who has headed the party’s most radical wing since its early days, has attracted public attention. The Thuringian branch of the AfD was the first to be classified as “right-wing extremist” by the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution in 2021.

From 2014 to 2024, the region has first been governed by a one-seat left-wing majority under Linke minister-president Bodo Ramelow (2014-2020), the first regional government under Linke leadership in Germany, and then by a minority government still led by Ramelow and tolerated by the Christian Democratic CDU (2020-2024). In 2020, the regional leader of the Free Democratic Party (FDP), Thomas Kemmerich, briefly served as minister-president after FDP, CDU, and AfD members voted in his favor in a surprise third round of voting. Kemmerich was forced to resign 28 days later following fierce backlash from federal politicians of all centrist parties, including his own, over his election with AfD support (Opelland, 2020).

The election held in Thuringia on September 1, 2024 was a milestone in contemporary German politics in at least two ways. First, as had been expected from pre-election polls, it saw the right-wing extremist AfD become the largest party in a regional parliament for the first time in post-war Germany, winning over a third of the seats. Second, the election led to the formation of a new minority coalition under CDU leader Mario Voigt, nicknamed the “blueberry coalition”. This coalition involves the CDU, the social democratic SPD, and the new ‘left-nationalist (Steiner & Hillen, 2025) or ‘left-authoritarian’ (Thomeczek, 2024) Sahra-Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW).

This paper analyzes the results of the regional election held in Thuringia on September 1, 2024, in three steps. First, we provide background information on the election, including the electoral system and campaign. Second, we look into the results of the election, reviewing spatial patterns of party support and the way they relate to socio-demographic variables. Third and finally, we review the government formation process and the consequences of the vote for German and European politics.

Electoral system

Thuringia uses a mixed-member proportional system similar to the one in use at federal level before 2023. Every German citizen residing in Thuringia has two votes. With their “constituency vote“ (“first vote”), they select a candidate in one of the region’s 44 constituencies. The candidate obtaining the most votes is elected (first-past-the-post). With their ”regional vote” (“second vote“), they select a regional list of a party. Each regional list obtaining at least 5% of regional votes is entitled to seats in the regional parliament. At least 44 list seats are distributed to the parties using the Hare-Niemeyer/Hamilton method such that the total seat share of each party matches their share of regional votes. If a party obtains more direct seats than it is entitled to, it keeps these and additional compensatory seats are assigned to the other parties, thereby increasing the size of the regional parliament beyond 88 seats. This last happened in 2019, when the CDU won one more direct seat than it was entitled to. Unlike in the neighboring Länder of Brandenburg and Saxony, where winning at least one direct seat allows parties to obtain list seats even if they did not reach the 5% threshold, such a rule (Grundmandatsklausel) does not exist in Thuringia.

Campaign

Incumbent minister-president Bodo Ramelow (Linke), whose party had turned out in first place in 2019 (31%), faced much less favorable odds in 2024. At 50%, his approval rating was still relatively high but had decreased significantly from his record 70% in 2019 (Ehni, 2024). More importantly, his Linke party polled at record lows nationwide, remaining below the 4% mark since January 2024. In Thuringia, the party appeared to have lost about half of its 2019 electorate, obtaining just 11% to 20% of the vote in pre-electoral polls. 1 The Linke’s demise in public opinion coincided with the rise of the Sahra-Wagenknecht Alliance (BSW), a Linke splinter founded by former party leader Sahra Wagenknecht in early 2024 on a left-wing conservative platform (Thomeczek, 2024) reminiscent of Eastern European post-socialist parties. In Thuringia, where former Eisenach mayor Katja Wolf led the regional BSW section, the Linke was consistently trailed by the BSW in the polls from May 2024 onwards. Thus, Ramelow faced a paradoxical situation, being both by far more popular in a hypothetical direct election than its fellow lead candidates Björn Höcke (AfD), Mario Voigt (CDU), and Katja Wolf (BSW), and the leader of the weakest of the four major parties (Sänger & Fiedler, 2024). Unsurprisingly, the Linke’s campaign focused on their leader’s record in government. The party used election posters with Ramelow’s picture and the unusual caption “Christian. Socialist. Minister-president,” but without the Linke logo (ibid.). It also published a comprehensive “government program” that promised to combine “humanity, strength, and justice” (Die Linke, 2024).

Symmetrically, the CDU’s “government program” emphasized the need for political change to “bring back order in Thuringia” (“Thüringen wieder in Ordnung bringen”) with a strong focus on the economy, education, security, and migration (CDU, 2024). The economy and education are key competences traditionally assigned to the CDU by voters, as was again confirmed in voting-day polls (Infratest dimap, 2024). Security and migration, on the other hand, were both salient issues in federal politics and the main assigned competences of the AfD in Thuringia. In line with his party’s federal “incompatibility decision,” Voigt ruled out any government coalition with the AfD or Linke, while leaving open the possibility of a coalition agreement with the BSW (Spiegel, 2024).

The five priorities listed by the BSW in its political program underlined the party’s idiosyncratic political platform. Their program put forward “an uncompromising engagement for peace” in Ukraine through a ceasefire and negotiations; “defending the interests of normal families and workers”; preserving “excellent schools independent of parental income”; preventing “uncontrolled migration”; and promoting “free speech […] against cancel culture” after the COVID pandemic (BSW, 2024: 4-5). One of Sahra Wagenknecht’s core talking points since 2022, the demand for a negotiated “peace” and rejection of help to Ukraine and US defense infrastructure on German soil was a highly unusual feat in a regional political campaign, giving a unique geopolitical dimension to the Thuringian vote. In Summer 2024, the BSW leader warned that her party would not become part of regional governments that do not “take a clear position at federal level for diplomacy and against preparing for war” (SZ, 2024). If it would become part of a government coalition, the party hoped to leverage its access to the Bundesrat, Germany’s upper chamber representing the 16 states, to put “peace” on the parliamentary agenda. However, it was unclear during the campaign how the party intended to impose this view given that its main potential allies, the CDU and SPD, held a clear pro-European and pro-Ukrainian stance on the federal scene. But despite its unclear strategic value beyond election day, the BSW’s message did seem to reflect the sentiments of a significant fraction of the Thuringian electorate. This was partly acknowledged by other party leaders, with Voigt (Spiegel, 2024b) and Ramelow (Vorreyer, 2024) both also calling for ‘more diplomacy’ as part of their political campaign.

The title of the AfD’s electoral program (AfD, 2024), “Everything for Thuringia” (“Alles für Thüringen”), directly echoes the prohibited nazi motto “Everything for Germany” (“Alles für Deutschland”) used by Björn Höcke in a public gathering in 2021, a use for which the party leader was fined €16,900 by the regional court of Halle in July 2024 (LTO, 2024). Beyond this provocation, the AfD strived to normalize its image as a potential government party. The AfD published the longest of all major parties’ political programs, in which it purposefully avoided the use of words that caused a major public backlash (“remigration”). Höcke also took part in televised debates with other lead candidates, a relatively recent phenomenon in the German media space. At the same time, the party did not significantly moderate its policy stances.

The SPD, Greens, and FDP’s lists were headed by leading figures of their respective regional party sections: vice-minister-president Georg Meier (SPD), vice-president of the Landtag Madeleine Heifling (Greens), and member of the Landtag Thomas Kemmerich (FDP). At the federal level, all three parties were members of the so-called “traffic-light coalition” led by Olaf Scholz, which had been plagued with record-low approval rates since mid-2023. Whilst being the direct target of attacks from AfD, BSW, CDU, and Linke, the three parties struggled to play any major role in the campaign, with the SPD falling below 10% in opinion polls in January 2024 and their two coalition partners both failing to reach the 5% threshold. 2 The Greens and the FDP’s appeal in Thuringia has historically been low, while the SPD has obtained relatively weak results in the regional since 1999, when Ramelow first led the then-PDS’s Landtag campaign. 3

Results

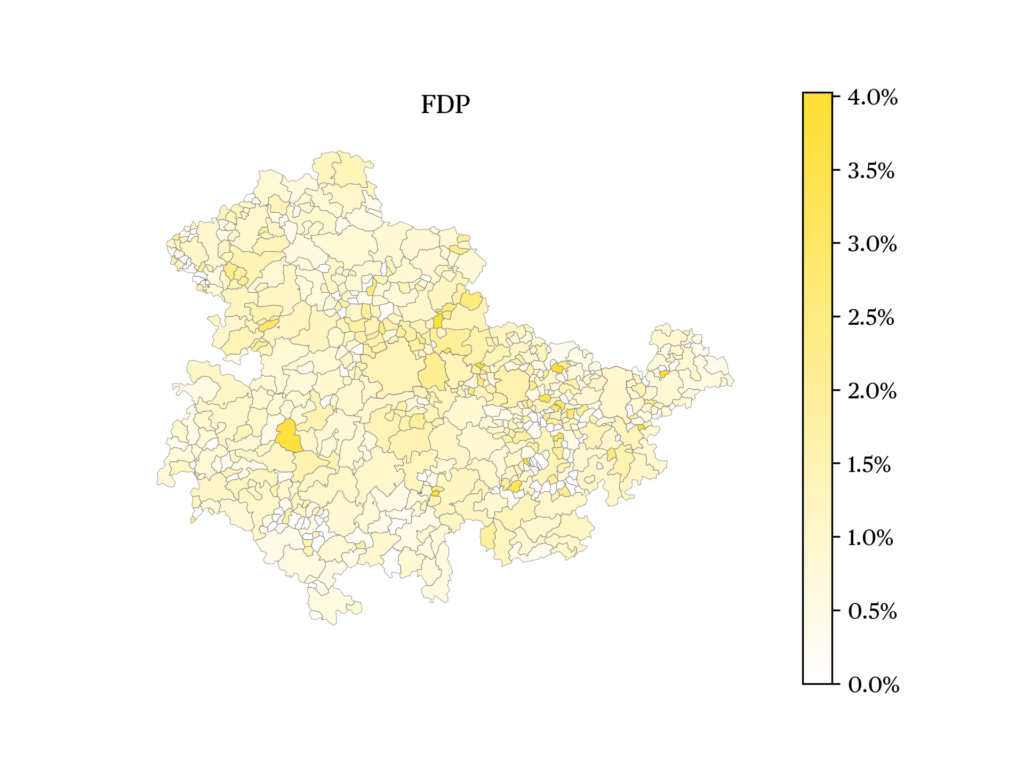

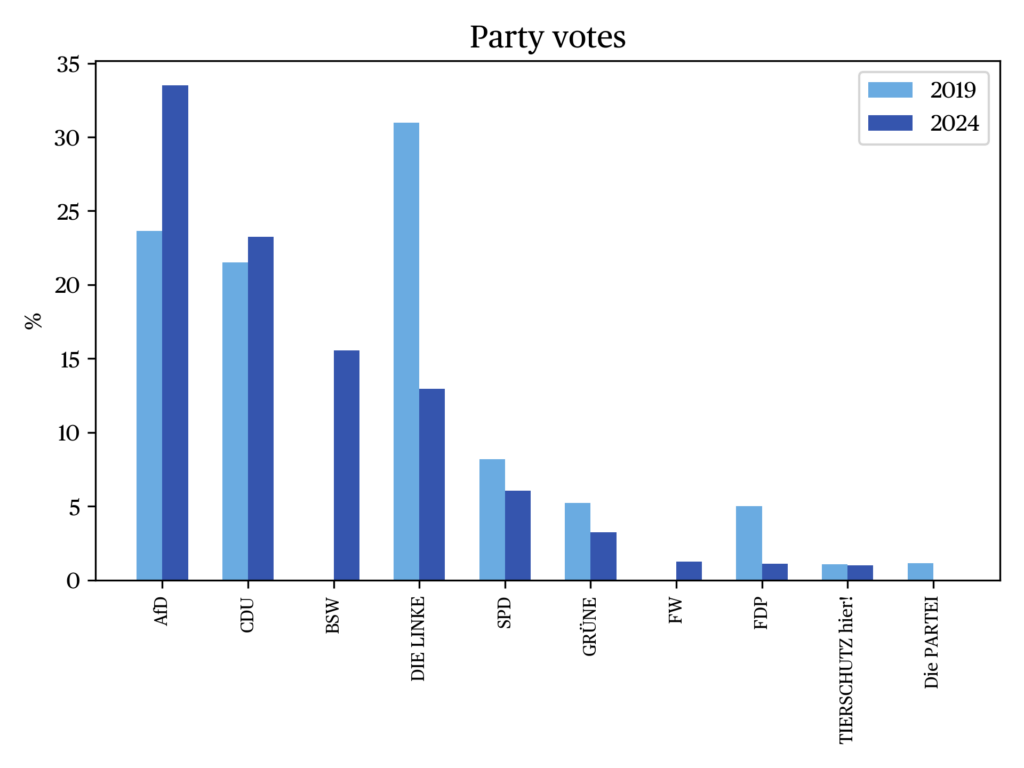

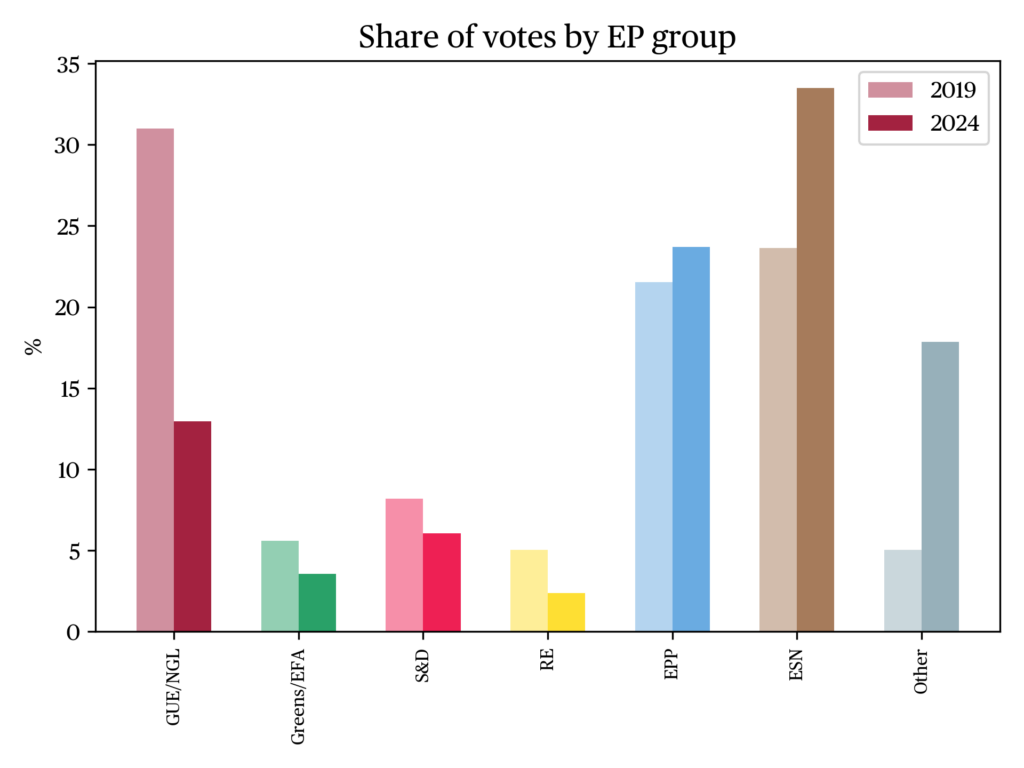

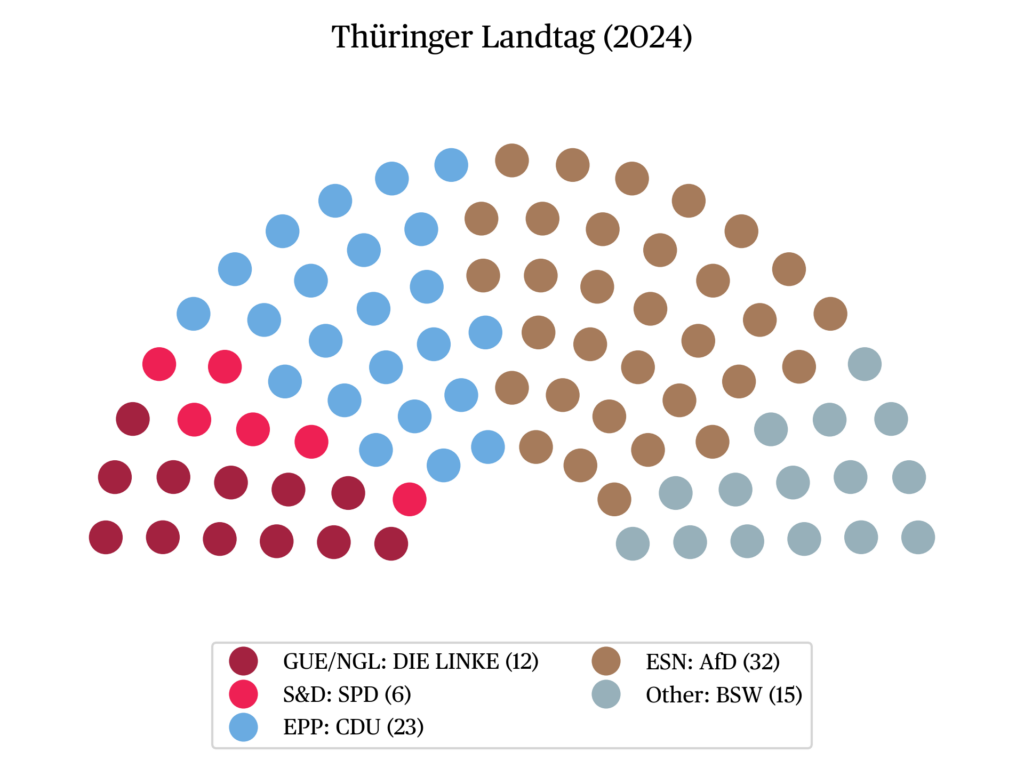

On election night, the AfD overperformed pollsters’ expectations, winning 32,8% of the vote and 32 seats. The CDU came in second with 23,6% and 23 seats, followed by the BSW with 15,8% and 15 seats, underperforming opinion polls. Ramelow’s Linke more than halved its 2019 support, winning 13,1% and 12 seats. The SPD, Greens and FDP obtained just above 10% of the vote in total, of which 6,1% went to the SPD―a record low in any regional election, resulting in only 6 seats―and 3,2% and 1,1% went to the Greens and FDP, respectively, who both failed to retain any parliamentary representation. Under the backdrop of strong mobilization both for and against the far right, turnout reached an all-time high since 1994, at 73.6% (2019: 64.9%).

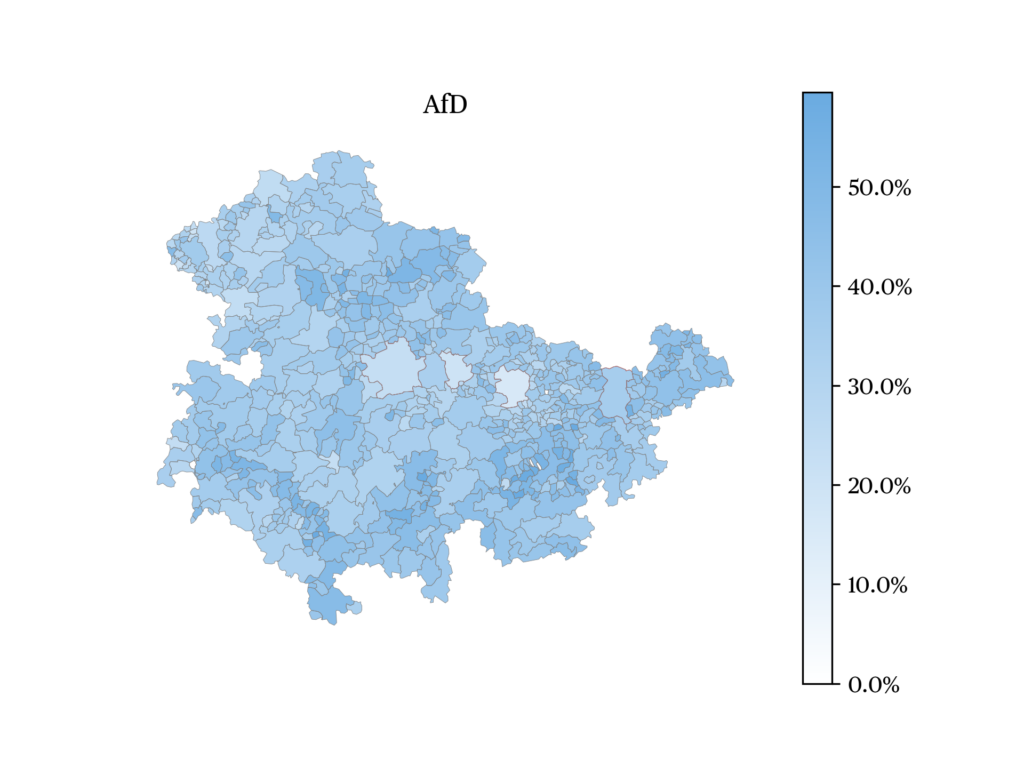

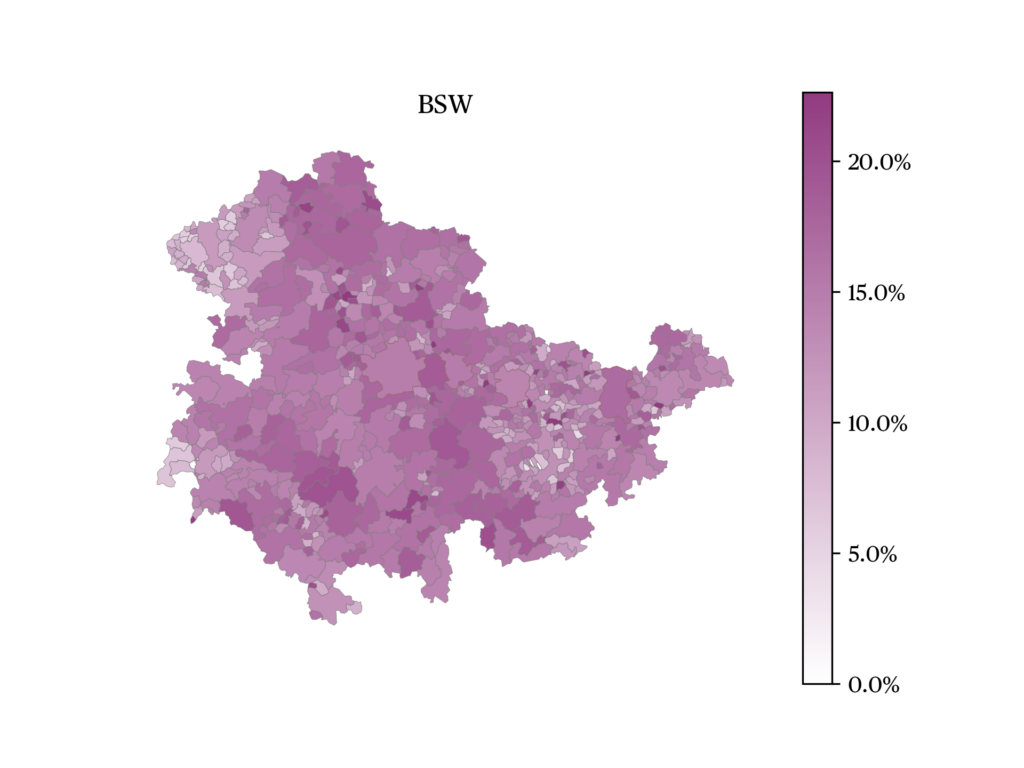

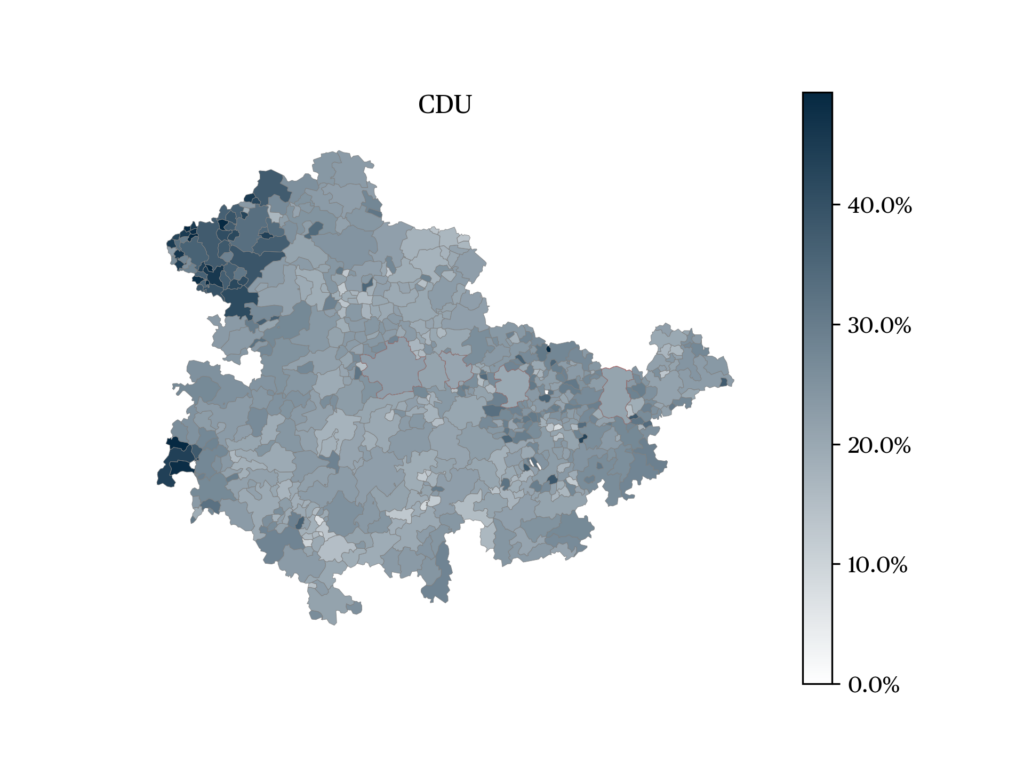

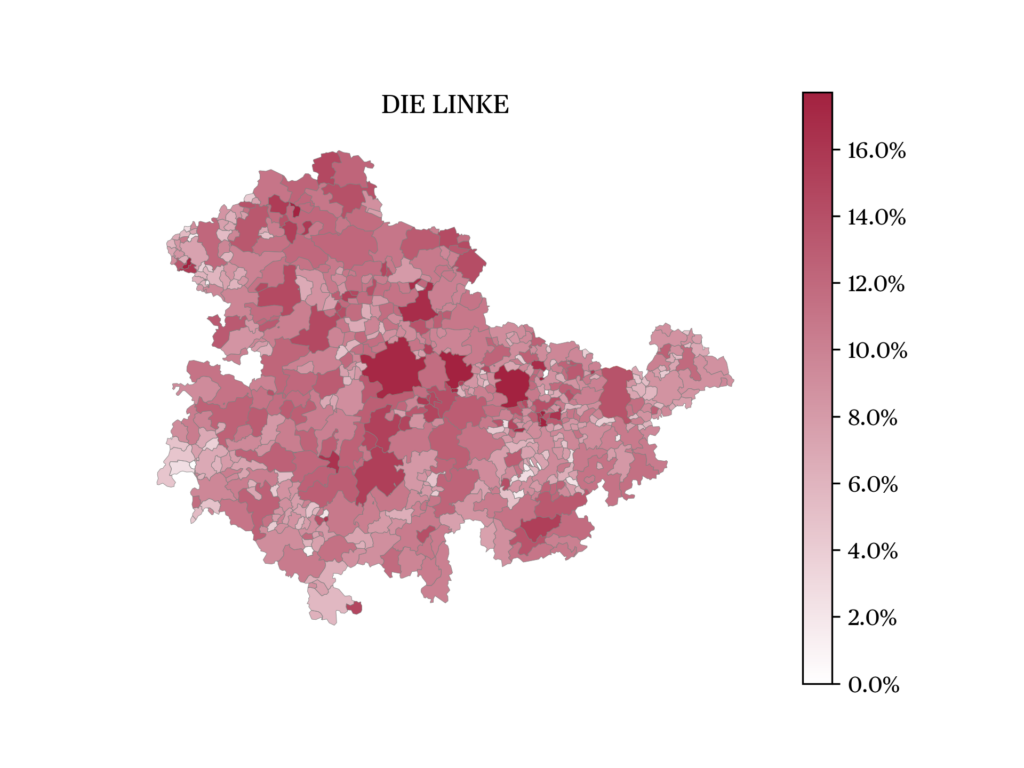

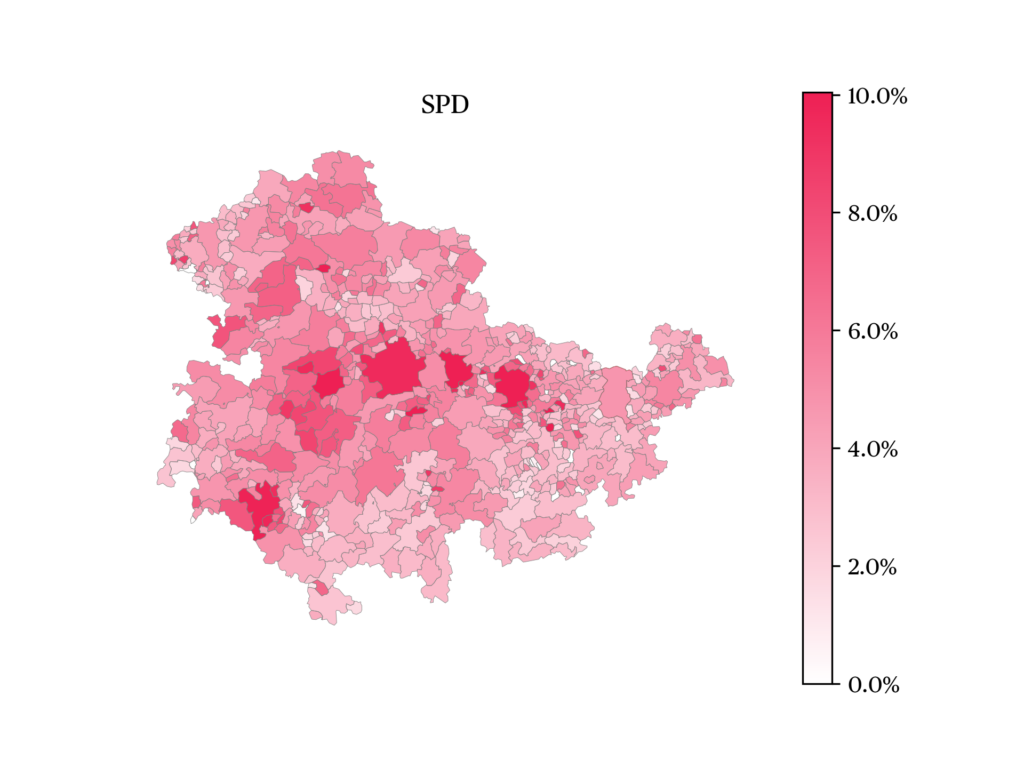

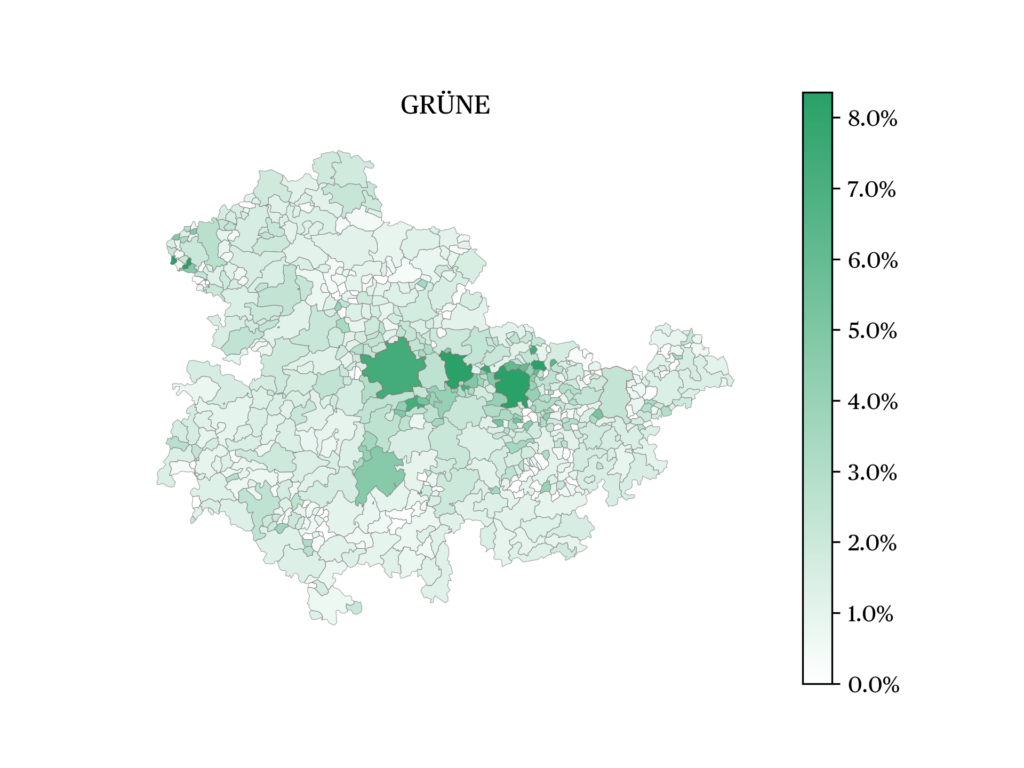

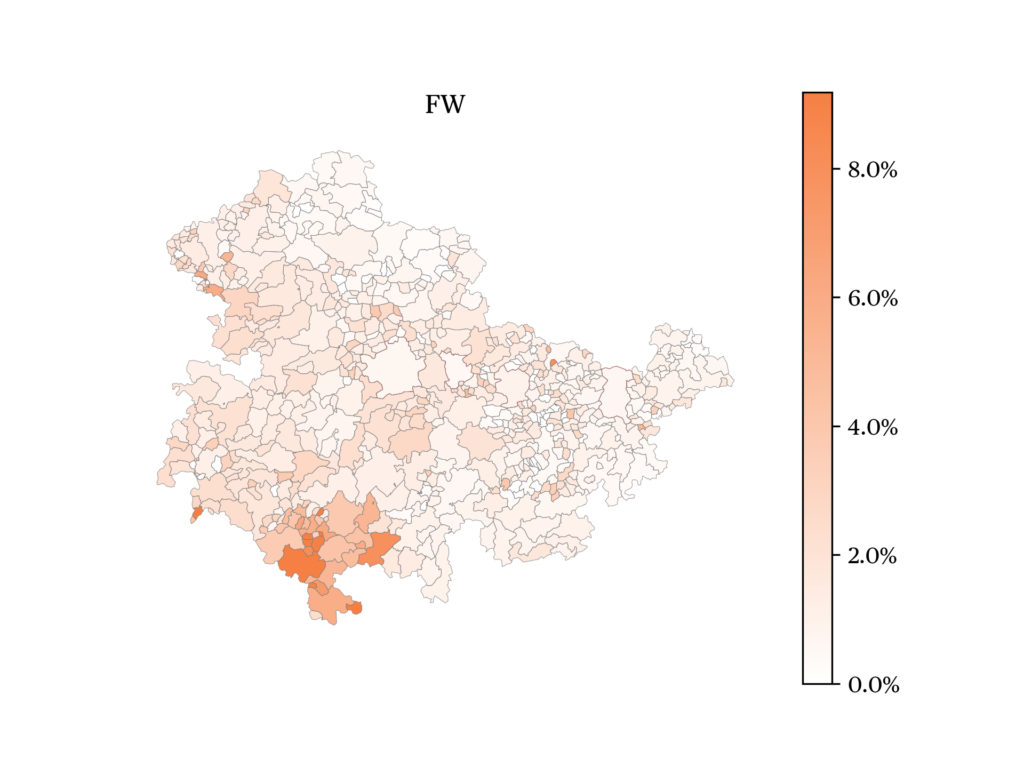

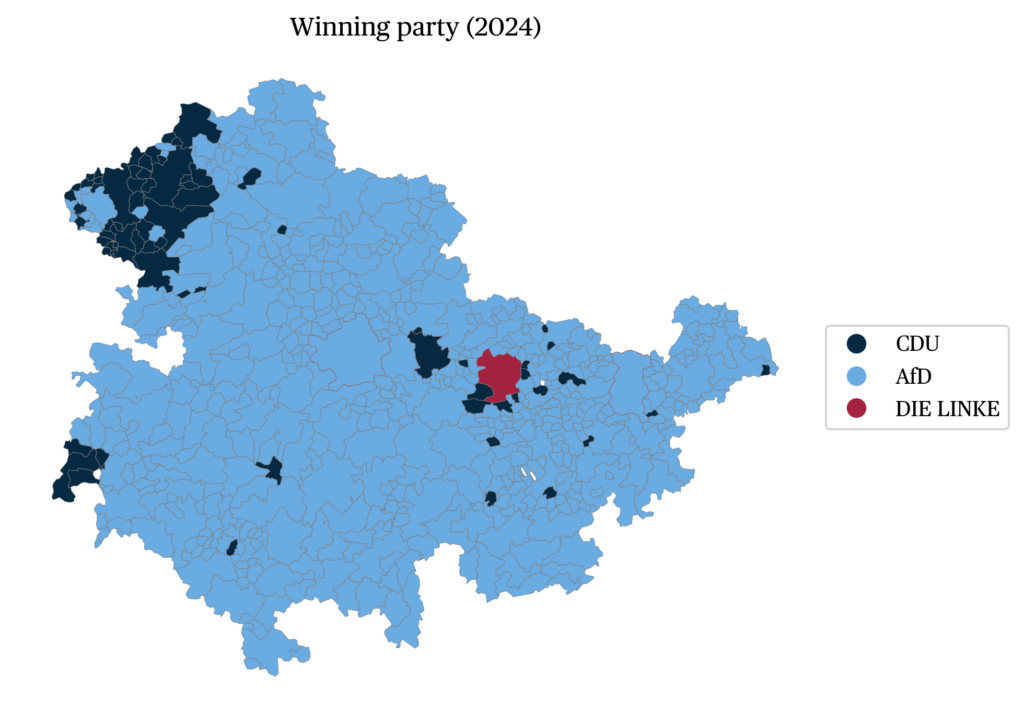

The AfD won a plurality in 87% of Thuringian municipalities, including the state capital of Erfurt and Gera, the region’s third largest city. The Linke, who still came out on top in over a third of municipalities in 2019, won its only municipality in Jena, the state’s second largest city and home to Thuringia’s largest university. The CDU won a plurality in about one in ten municipalities, mostly located in the two smaller Catholic regions in the North-West (Eichsfeld) and South-West (Geisa), as well as in the city of Weimar. The AfD’s results appear weaker in most larger cities than in rural areas, with the notable exception of the Eastern city of Gera, which has been described in the media as a “hotspot” of far-right extremism (Duwe et al., 2024). In contrast, the Linke, SPD and Greens perform significantly better in urban centers than in rural municipalities. Finally, in the Franconian district of Hildburghausen, on the border with Bavaria, the Free Voters (FW) locally received more than 10% of the second votes.

Voting-day polls confirm the dominance of the AfD in most demographics (Infratest dimap, 2024), with three major exceptions: in large cities, the CDU obtains slightly more votes (24%) that the AfD (22%); among voters above the age of 70, the AfD takes only third place with 19% behind the CDU (31%) and Linke (20%); finally, the CDU also wins over the AfD among the self-employed (32% to 30%), and similarly, among individuals with higher education (25% to 21%). While a significant gender gap exists for the AfD, with 38% of men but just 27% of women casting a ballot for the far-right party, this gap is much less pronounced for other parties and still allows the AfD to take first place among women. Voting-day polls also show that the AfD holds a particularly strong advantage among first-time voters, with 38% compared to just 17% for the second-placed party, the Linke; among voters with a basic level of education (44%); and among voters with a “bad economic situation” (51%).

To better understand the interplay between different demographic variables on the result of the vote, we ran a multivariate regression analysis (weighted least squares) over the municipality-level results, testing the parties’ performance (dependent variables) against the share of catholics, average income, population density, and share of foreign residents (independent variables). The results are shown in Figure b. The share of Catholics amongst the population has a statistically significant, positive effect on the CDU vote and a negative effect of lower magnitude on the Linke, AfD, SPD, and BSW vote. In line with exit polls, income affects the AfD vote and abstention negatively and the CDU, Linke, and SPD vote positively. Population density has no significant effect on the CDU and BSW vote but affects left-wing vote positively and the AfD vote and abstention negatively. Finally, the share of foreign residents in the population has a weakly significant, negative effect on the AfD vote (p = .026), no effect on the CDU and BSW votes, a moderate positive effect on the left-wing vote, and a negative effect on abstention. Due to a high degree of correlation between earnings, social security benefits, educational levels, and urbanity levels, similar results can be obtained by replacing income with the proportion of voters with college education, the degree of urbanization, or the inverse proportion of social security benefit recipients. Income also negatively correlates with the proportion of asylum seekers in the population. This makes it difficult to conduct a differential analysis of the effects of income and the presence of asylum seekers at this level. The four variables explain over 60% of the variance of the Linke, AfD and SPD vote and about 50% of the variance of the CDU vote. With a variance inflation factor (VIF) of 1.2–2.6, the coefficients are interpretable.

Figure b · Results of the regression analysis (N=467, weighted by number of registered voters).

| Linke | AfD | CDU | SPD | BSW | Non-voteb | |

| Catholics | -0.0002 * | -0.0007 * | 0.0016 * | -0.0001 * | -0.0005 * | 0.0001 |

| Income | 0.0027 * | -0.0045 * | 0.0023 * | 0.0021 * | 0.0006 | -0.0072 * |

| Densitya | 5.309 * | -9.790 * | -0.5412 | 3.214 * | -0.0229 | -3.726 * |

| Foreign residents | 0.0021 * | -0.0012 * | 0.0000 | 0.0016 * | 0.0007 | -0.0037 * |

| Intercept | -0.0182 | 0.4035 * | 0.0817 * | -0.0396 * | 0.0895 * | 0.5605 * |

| R² | .651 | .646 | .488 | .666 | .162 | .168 |

* Significant at level p < .05. Municipalities that underwent territorial changes since 2020 are missing as income data is available only for 2020. Sources: 2021 German census, 2020 income statistics, Regional Statistical Office of Thuringia.

a Coefficient multiplied by 10-5.

b Non-voters and invalid votes.

When looking at the residuals of the multivariate analysis (i.e., the difference between the predicted result of the party in a municipality according to a municipality’s demographics and its actual result), a few outliers emerge. Most significantly, the Linke and Greens overperform in Jena (+1.9 pp and +2.3 pp respectively) while the AfD overperforms in Gera (+3.2 pp).

Overall, the AfD appears to be the unequivocal winner of the 2024 regional election, winning in most demographics with the exception of the most educated and elderly. The right-wing extremist AfD can now position itself as the dominant “Volkspartei” (“mass party”) in Thuringian politics, claiming an electorate that spans beyond religious, class, and territorial cleavage lines, while other parties appear increasingly reliant on their core voter bases. The BSW succeeds in entering the regional parliament and capturing a significant share of the Linke’s former electorate. The CDU, while making small gains (+1.9 pp with respect to 2019), loses voters to the two populist parties. The CDU and SPD both collect the remaining votes of a shrinking center, whose only remaining strongholds are located in two small Catholic regions and in cities. The Linke and Greens remain relatively strong in more urban environments, especially in Jena, but lose significant momentum compared to previous terms. Finally, with just above 10% of the vote and 6 seats out of 88, the parties of the incumbent federal coalition suffer a catastrophic defeat.

Government formation

The new Thuringian Landtag held its constitutive session on September 26 and 28. The first day of debates proved chaotic after AfD Father of the House, Jürgen Treutler, who presided the session as the parliament’s oldest member, repeatedly rejected CDU requests for allowing a vote on amending the Landtag’s rules of procedure. The CDU and BSW sought to modify the rules of procedure to explicitly allow parliamentary groups other than the largest in parliament (i.e., the AfD’s) to suggest candidates for president of the Landtag. Facing Treutler’s refusal, the CDU called on the state constitutional court to decide on the matter (MDR, 2024). The next day, the constitutional court gave way to the CDU’s demand and the Landtag reconvened on September 28. After amending the rules of procedures, the parliament elected CDU member Thadäus König as president of the Landtag by 55 votes to 32 for AfD candidate Wiebke Muhsal and one abstention. In the subsequent election of the Landtag’s three vice-presidents, the parliament also rejected Muhsal’s candidacy by 41 votes and 15 abstentions, instead electing a BSW, an SPD and a Linke member as vice-presidents. This is in line with the classic ‘firewall’ practice in German politics, whereby centrist and left-of-center parties never support far-right MPs when they stand for elected office.

The government formation process took longer than usual. As the CDU had excluded any cooperation with the Linke and all parties refused to form a coalition with the AfD, the best achievable outcome was a three-party minority coalition of the CDU, BSW, and SPD. The three parties hold 44 out of 88 seats in the Erfurt Landtag, falling short of a majority by one. The negotiations on the new coalition model, nicknamed the “blueberry” by political scientist Karl-Rudolf Korte hinting at the three parties’ colors (black, purple, and red), were slowed down by Sahra Wagenknecht’s interference and internal conflicts within the BSW. After an initial agreement was reached between the regional parties in mid-October, the BSW federal leadership criticized what they described as an insufficiently clear commitment to peace in the draft document, voicing fears that the future Landtag could approve of a potential deployment of US missiles in the region (MDR 2024b). The regional party section eventually approved the start of formal coalition negotiations in early November. After another month, the CDU, BSW, and SPD sections all voted in favor of the new coalition agreement, entitled “The Courage of Responsibility. Bringing Thuringia forward” (MDR, 2024c, 2024d, 2024e; Coalition agreement, 2024). The document states in its preamble that “The CDU and SPD see themselves as part of the tradition of Western European integration and Ostpolitik. The BSW stands for an uncompromising peace course.” It sets six priorities that define a centrist to center-right course: guaranteeing education by reducing class cancellations in schools; improving the local availability of healthcare; reducing bureaucracy and creating a regional innovation fund; organizing migration; digitizing the state; and reforming the state-municipal relationship towards more communal autonomy.

Outlook

Three regional elections took place in Eastern German states in September 2024, in Thuringia, Saxony, and Brandenburg. All three elections saw the parties of the federal “traffic light” coalition incur losses, although with different outcomes (in Brandenburg, the SPD remained the largest party). In particular, the Greens lost parliamentary representation in two of the three regions, managing to pass the 5% threshold only in Saxony. The FDP, whose lead candidate Kemmerich had been a marginal figure within the party since the 2020 government crisis, lost all of the seats it held in Thuringia. These negative results likely contributed to the further fragilization of the federal coalition which would collapse two months later, leading to snap elections being held in late February.

Between September 2024 and February 2025, the Linke significantly improved its performance in federal opinion polls while the BSW appeared to be losing momentum. In the federal election on February 21, Thuringian voters placed the AfD first with 38,6% of second votes, while only 36% of Thuringian voters supported one of the parties in the “blueberry” regional coalition―less than the AfD’s vote share alone. In Thuringia, the strengthening of the AfD and the simultaneous demise of the BSW means that the new centrist coalition is going to face an even stronger far-right opponent in the current election cycle, with only conditional support from Linke on its left flank. At the same time, the AfD comes closer to the 45-46% mark typically needed to obtain an absolute majority in parliament. As of March 2024, the scenario of an AfD majority in the next Landtag has become a serious possibility, and the continued formation of weak center-right or center-left minority cabinets tolerated by either the Linke or CDU, the only viable alternative.

The 2024 state election in Thuringia also had an unusual European dimension, with the BSW (and AfD) calling for a rapid ceasefire rather than support for Ukraine and the BSW’s federal leadership insisting on a “commitment to peace” and rejecting the deployment of US missile systems. On these issues, the BSW and AfD appear to align with some of their Central and Eastern European counterparts (e.g., Hungary’s Fidesz or Slovakia’s Smer-SD) with whom they share both populist demands and, especially for the BSW, an ambivalent relationship to Russia and the West partly anchored in the Socialist past. Eventually, however, the BSW’s capacity to impose its geopolitical agenda proved rather limited: the coalition partners merely acknowledged their diverging views in the preamble to the coalition agreement. Although foreign policy issues were present in the campaign, they probably played only a minor role in the outcome: only 17% of BSW voters and 5% of all voters cited the war between Ukraine and Russia as the main reason for their vote. While the East-West cleavage within the Thuringian party system has become more salient, it was nonetheless less influential than cleavages on issues such as migration, the economy, or internal security, or the spillover effects of federal political dynamics.

The data

References

Oppelland, T. (2015). Die thüringische Landtagswahl vom 14. September 2014: Startschuss zum Experiment einer rot-rot-grünen Koalition unter linker Führung. Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen, 39–56.

Oppelland, T. (2020). Die thüringische Landtagswahl vom 27. Oktober 2019. Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen, 51(2), 325–348.

Steiner, N. D., & Hillen, S. (2025). Voting for the Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW)

from a Policy Space Perspective. German Politics, 1–25.

Thomeczek, J. P. (2024). Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht (BSW): left-wing authoritarian—and populist? An empirical analysis. Politische Vierteljahresschrift, 65(3), 535–552.

News articles

Duwe et al. (2024, 23 February). Ein “Hotspot” der rechtsextremen Szene. Tagesschau.

Ehni, E. (2024, 22 August). AfD in Vorwahlumfrage stärkste Kraft. Tagesschau.

Infratest dimap (2024, 1 September). Landtagswahl Thüringen 2024. Tagesschau.

LTO (2024, 14 May). LG Halle verurteilt Björn Höcke zu Geldstrafe von 13.000 Euro. Legal Tribune Online.

MDR (2024, 26 September). “Sie betreiben Machtergreifung”: Landtagssitzung unterbrochen – CDU ruft Gericht an. MDR.

MDR (2024b, 2 November). Sondertreffen des Thüringer BSW: Partei will bei Streitpunkt Krieg & Frieden “nachschärfen”. MDR.

MDR (2024c, 30 November). Thüringer CDU gibt grünes Licht für Brombeer-Koalition. MDR.

MDR (2024d, 7 December). Thüringer BSW stimmt für Brombeer-Koalition mit CDU und SPD. MDR.

MDR (2024e, 9 December). Auch SPD stimmt zu: Weg für Brombeer-Koalition in Thüringen frei. MDR.

Sänger, L. & Fiedler, C. (2024, 24 August). Wenn Beliebtheit nicht ausreicht. Tagesschau.

Spiegel (2024, 3 September). Thüringer CDU beschließt Gespräche mit BSW und SPD. Der Spiegel.

Spiegel (2024b, 29 July). CDU-Spitzenkandidat Voigt fordert mehr Diplomatie im Ukrainekrieg. Der Spiegel.

SZ (2024, 29 July). BSW will Friedensthema nicht opfern – Kritik an Wagenknecht. Süddeutsche Zeitung.

Vorreyer, T. (2024, 13 August). Um den Krieg kommen sie nicht herum. Tagesschau.

Programs

Die Linke (2024). Unser Thüringen. Menschlich. Stark. Gerecht.

CDU Landesverband Thüringen (2024).Wie wir Thüringen wieder in Ordnung bringen.

BSW Landesverband Thüringen (2024). Neustart für Thüringen. Damit sich was ändert.

AfD Thüringen (2024). Alles für Thüringen!

Coalition agreement (2024, 22 November). Mut zur Verantwortung. Thüringen nach vorne bringen.

Notes

- Polling data from wahlrecht.de (Umfragen Thüringen, Sonntagsfrage Bundestagswahl).

- Polling data from wahlrecht.de (Umfragen Thüringen).

- The Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) was the legal successor of the GDR’s Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED). It merged into the Linke in 2007.

citer l'article

François Hublet, Regional election in Thuringia, 1 September 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue