Regional elections in Finland, 23 January 2022

Josefina Sipinen

Researcher at University of TampereIssue

Issue #3Auteurs

Josefina Sipinen

Issue 3, March 2023

Elections in Europe: 2022

A new type of election in Finland

The first-ever county elections were conducted in Finland on 23 January 2022. The elections were held as a result of a health and social services (SOTE) reform, which is one of the largest administrative reforms in the country’s history. The key objective of the SOTE reform is to improve citizens’ equal access to and quality of basic public services throughout Finland, as well as contain the future cost increases of these services resulting from rapidly aging population.

In proportion to the country’s population (5.5 million), Finland has a large number of municipalities (309) in European comparison. Municipalities have their own right of taxation and they have been responsible for delivering most of the public services—thus far also health and social care services. For long, there has been a consensus between political parties that this is an inefficient way to organise health and social care, and that larger organizations than municipalities are needed to take on this responsibility. Both the aging population as well as very small population sizes in most municipalities (less than 5,000 inhabitants in almost half of the municipalities) have resulted in inequities and problems with access to and effectiveness of services. While those relying on public health care have experienced high waiting times particularly for specialist and primary care and social services, those with access to occupational health services have enjoyed access to services comparatively much more quickly (Couffinhal et al. 2016; Finnish Government 2022).

Despite the consensus regarding the importance of the SOTE reform, planning of the reform took approximately 15 years. The main bones of contention among parties were the number of counties or units responsible for organizing the services, individuals’ freedom to choose service providers, and the role given to the private section (Kangas & Kalliomaa-Puha 2018). The successive Sipilä government (2015–2019) even resigned five weeks before the 2019 Parliamentary Elections, when it became clear that the SOTE reform could not be delivered (Yle News 8.3.2019).

In June 2021, the current government of Prime Minister Sanna Marin (SDP) approved of a reform under which a total of 21 self-governing wellbeing services counties will be established. From the beginning of 2023, the responsibility for organising health, social and rescue services will be transferred from municipalities to these counties, which means an entirely new layer of administration (Finnish Government 2022). As an exception, the capital city Helsinki continues to be responsible for health, social and rescue services within its own area and, hence, does not participate in county elections. This is primarily because of Helsinki’s population size, for Helsinki is bigger than any of the other new regions being created. Municipalities of the autonomous region Åland Islands have not participated municipal elections before and will not participate county elections either.

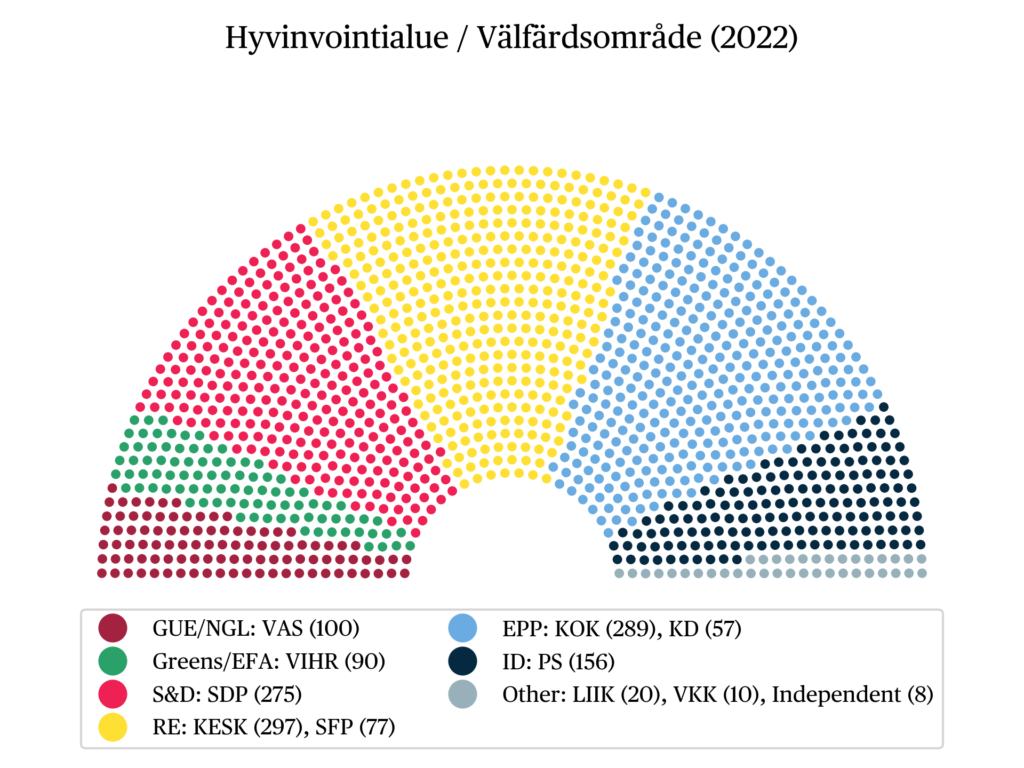

With reduced municipal tax rates, Finnish municipalities will continue to organise certain services, including child daycare, education, sports, and cultural services. The wellbeing services counties are not at least initially given the right of taxation. Instead, the counties receive their funds from the government, which raises its tax rate in proportion to decreased municipal tax rates. The highest decision-making power in each wellbeing services county will be exercised by a county council, whose members and deputy members will be elected in county elections. From 2025 onwards, county elections will be held every four years in conjunction with municipal elections (Finnish Government 2022). However, since the counties have no right of taxation (at least not yet), they must operate within the budget frame determined by the government, which emphasises the government/opposition divide also at the county level and reduces regional autonomy.

The reform should improve democracy in the sense that now, the eligible county residents get to directly select their representatives to county councils that are responsible for the decisions on social and health care. In the current (soon to be prior) model, several municipalities organized social and health jointly, and the representatives to municipalities’ joint boards were selected by the political parties.

The county councils have members who are on municipal councils and in parliament as well, which has raised concerns about conflicts of interest as well as centralization of power to the same people. One of the main reasons why MPs and other most well-known politicians stand as candidates in municipal and—from now on—county elections, relates to the Finnish open-list proportional representation electoral system with mandatory preferential voting (see e.g., von Schoultz 2018). Citizens are obliged to vote for one candidate and one candidate only. Every vote for a candidate is directly a vote for the party the candidate represents. Each candidate belongs to a list of a registered political party, or to an ad hoc non-party list of candidates. Within a party or other group, the candidate with the most votes ranks first on the list, the candidate with second most votes second etc. Seats are allocated based on the d’Hondt formula. Hence, the most popular politicians, the ”vote-getters,” have a significant role in contributing to their party’s vote share, meaning that it is hard for them to decline candidacy, although in reality their ability to fully engage in all representative roles is limited.

The electoral threshold—the minimum share of the vote which parties were required to achieve before acquiring seats in county councils—ranged between 1.3–1.7 percent, which corresponds to electoral threshold in large municipalities in municipal elections (Borg 2022: 99) and is much lower than in parliamentary elections. In other words, the electoral threshold in county elections was relatively low, which favoured small parties’ and groups’ chances of securing representation.

Results

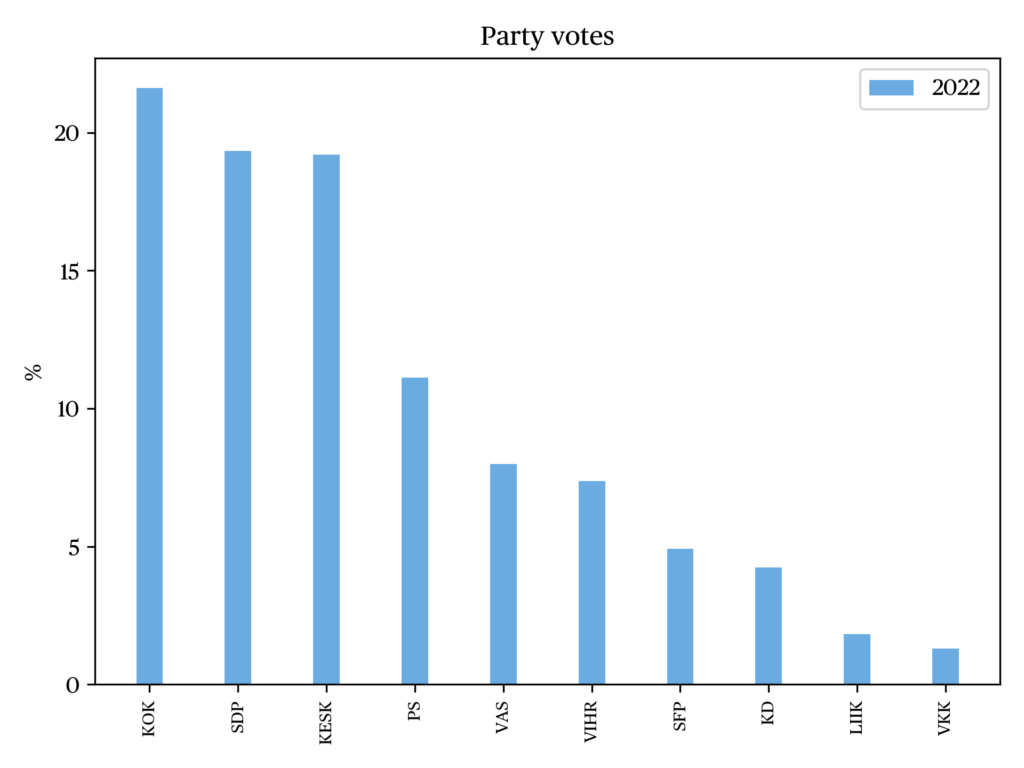

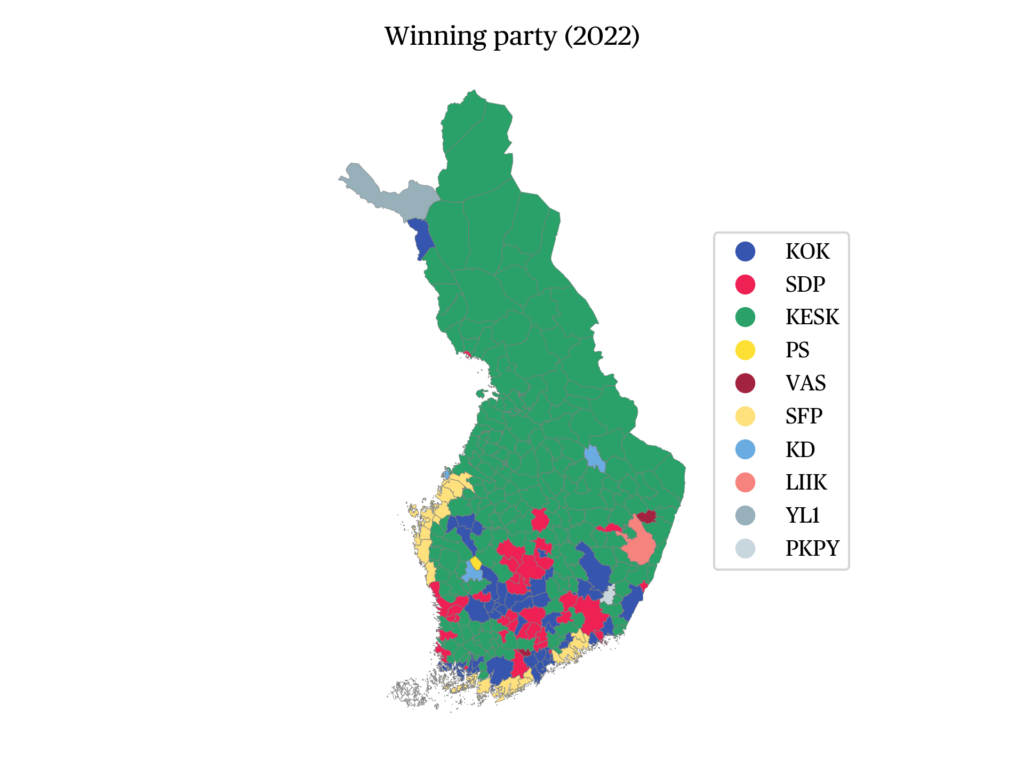

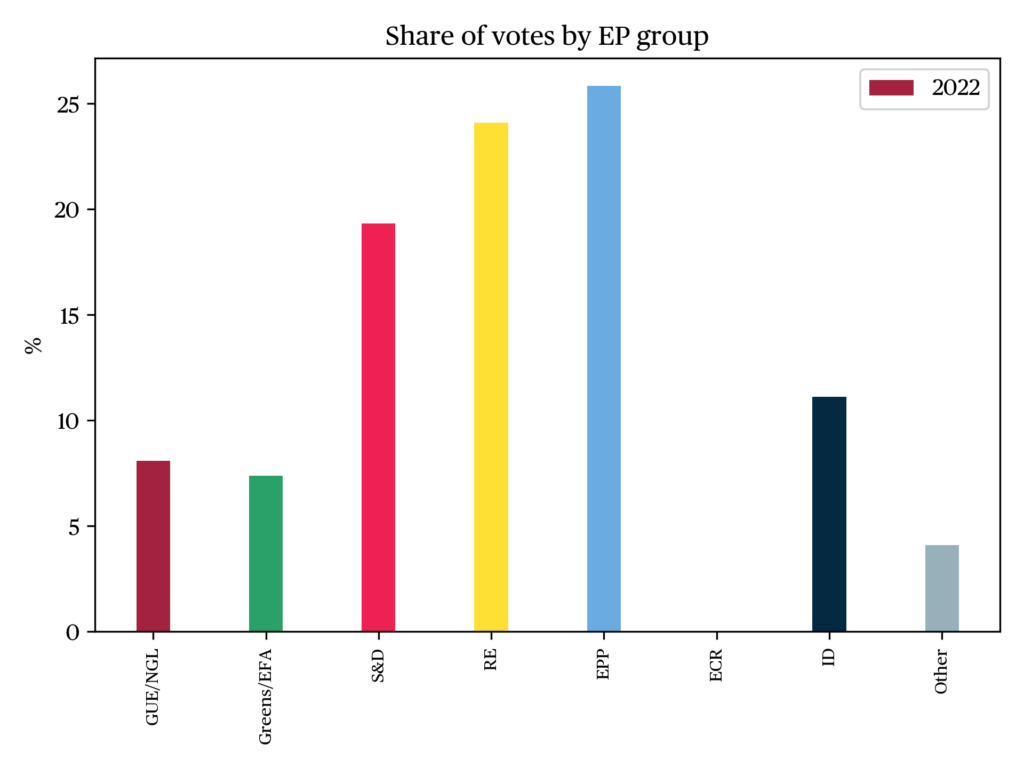

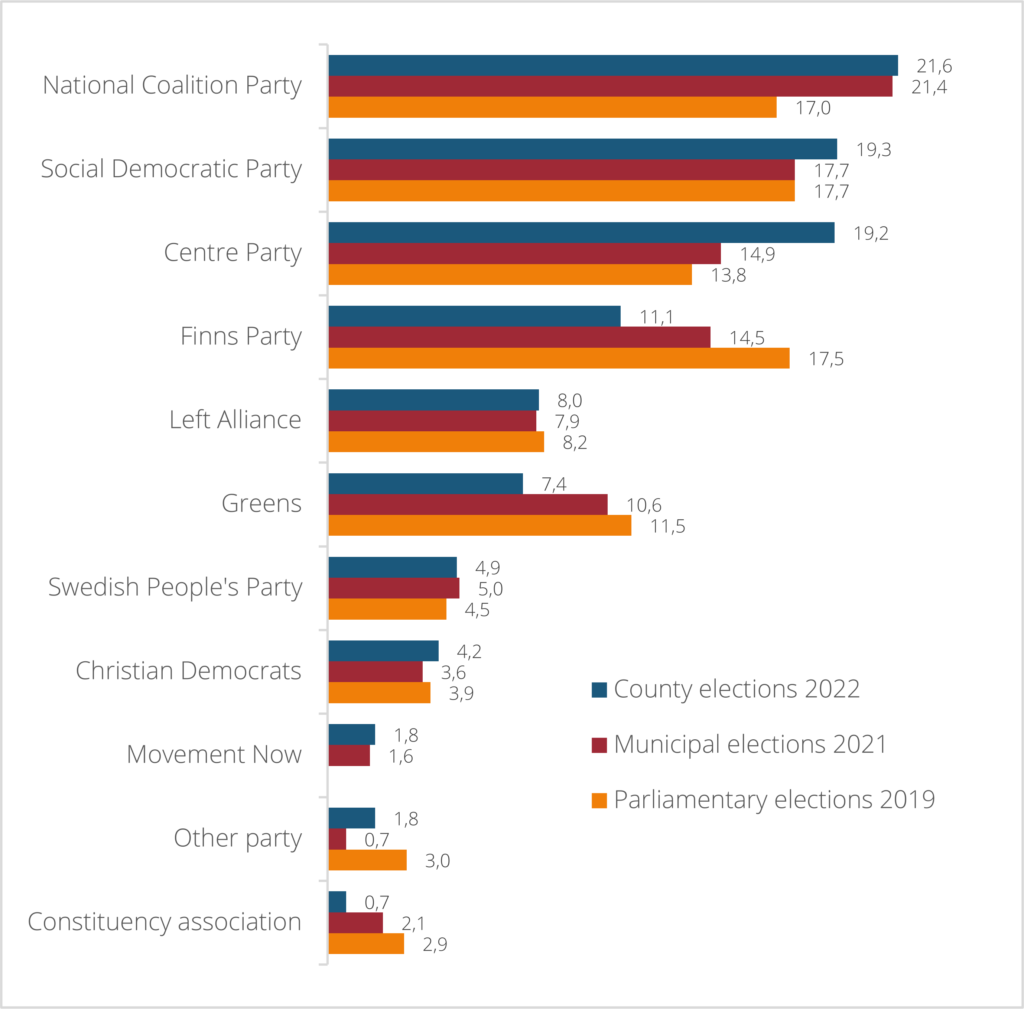

County elections focus on a very limited yet budget- wise significant issues. Finnish parties’ history and reputation regarding their expertise and emphasis on health care issues clearly affected their chances of securing support in the county elections. The parties who succeeded were those big old “catch-all” parties—the Social Democrats (SDP), the liberal/agrarian Centre Party, and the conservative National Coalition (NCP)—that have been key actors in building of the Finnish welfare state during the 20th century. After the Second World War, the Finnish party system remained rather stable, with the “big three” securing most power. The rise of the populist Finns Party from the beginning of the 2010s changed the status quo and produced a situation of four about equally sized large parties in the parliament (Arter 2016; Borg 2019; Raunio 2022). However, this fragmentation characteristic to the past decade did not show in the County elections, were the big three got 19.2–21.6 percent of the votes each (Figure 1). In contrast, the Finns and also the Greens that have gained support in recent parliamentary and municipal elections by focusing on sociocultural issues (such as immigration, minority rights and environment) lost support.

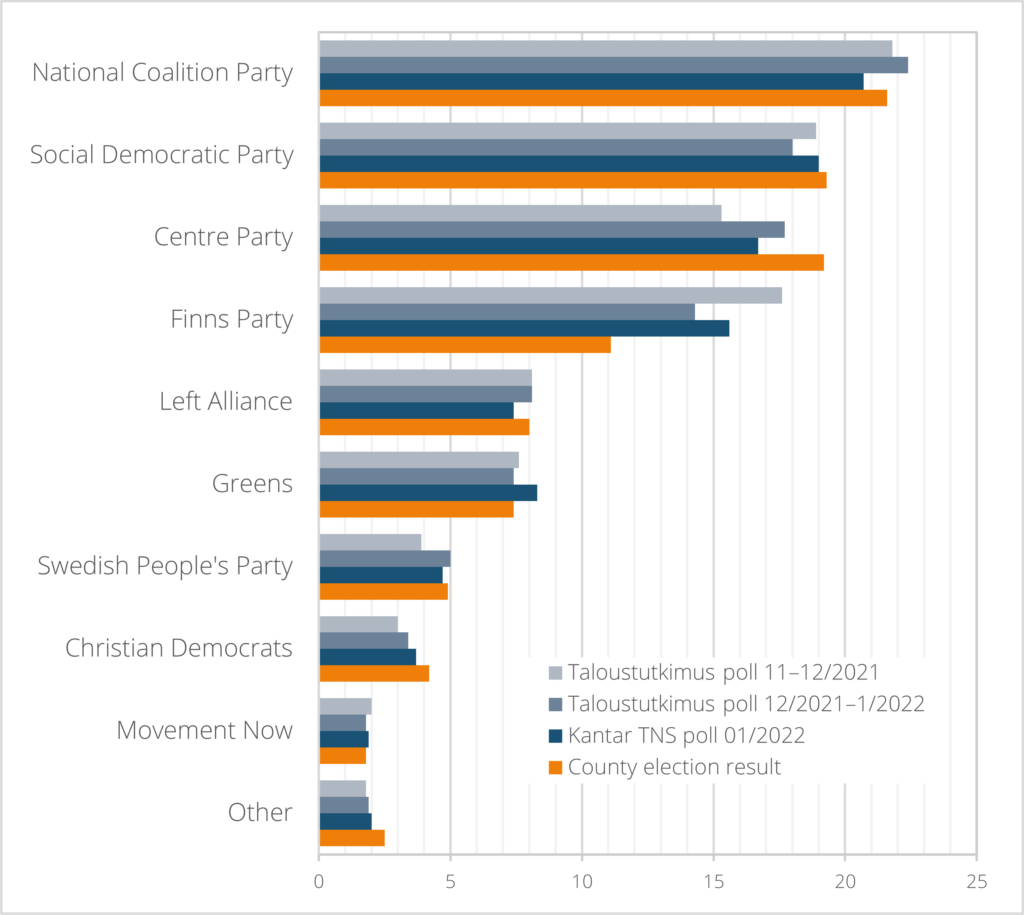

The NCP was the biggest party with 21.6 per cent of all votes cast (Figure a). The SDP came second and the Centre Party third, although the latter two had only a 0.1 percentage point difference in their vote share. In general, the “big three” were all on home ground in terms of the themes discussed in the county elections. As the main opposition party as well as the winner of four municipal elections in row (between years 2008–2021) the NCP was the clear favourite also in county elections, as can be seen from the latest polls released under the elections and reported in Figure b.

In the campaign debates, the NCP stood out as an alternative to the leftist politics of the government by discussing about taxation and highlighting the role of the private sector in providing health and social services. To the left parties in the government (the SDP and the Left Alliance), strengthening the public sector was an important aim in the SOTE reform. The liberal/agrarian Centre Party, also in the government, was very much on home turf in regional elections, because it draws its support mainly from rural municipalities. In their county elections manifesto, the Centre Party promised at least one social and health care center to all 293 municipalities. Generally, although the main purpose of the SOTE reform is to contain growing expenses of health and social care expenses, many parties gave similar pledges about improved services. Thus, instead of giving voters a realistic idea about the impact of the reform, parties more likely accelerated voters’ expectations.

The second main opposition party, the populist Finns Party, which has gained growing support in the 2010s with its anti-immigration and anti-EU agenda, was not a credible challenger due to its weak profile on health and social issues. As Figure b shows, the party fared poorly in comparison to the previous municipal and parliamentary elections. The Finns Party’s result was poor also in comparison to the polls released under the elections (Figure b). The Taloustutkimus poll collected in November/December predicted over 17 percent support for the party, while eventually the party only gained 11.1 percent of the total vote. Another loser in the elections was the Greens, which like the Finns Party has a rather narrow profile concentrating mainly on environmental and minority rights issues (Borg 2020). To summarise, the so-called GAL–TAN or sociocultural division—which contributes to the support of especially the Finns and the Greens (see also Westinen 2015)—had much less impact in these elections, whereas the traditional left/right and center/periphery cleavages were emphasised.

Another explanation to the success of the NCP and the downfall of the Finns Party and the Greens relates to the low turnout rate (47.5%) of the elections. Among both lawmakers and scholars, the turnout rate was considered poor (Yle News 23.1.2022), although it hardly came as a surprise after the historically low turnout rate in municipal elections (55.1%) held in previous summer. Reasons for low turnout likely relate to county elections being completely new type of elections, of which voters had no prior experience, but also because the focus was on issues not equally important to all voter groups. For instance, young voters deem health and social issues much less important reason behind their motivation to vote compared to elder age groups (Borg 2022). Third potential reason for low turnout is linked to the short campaign period and parties’ modest campaign budgets. The county elections were held in the end of January, and the parties began their campaigns only after the new year. Knowing how parliamentary elections will be held next year (Spring 2023), parties did not invest too much money on “second-order elections.” Also, postponing the 2021 municipal elections from April to June due to the difficult COVID-19 situation yielded costs to parties that had already began their campaigns when the decision of postponing the elections were made in March (Helsingin Sanomat 8.11.2021).

Low turnout rate usually reduces the support of the Finns and the Greens whereas the NCP has reliable voters from election to election mainly because their voters have higher-than-average socioeconomic status. In contrast, among the voters of the Finns and the Greens the level of partisanship is lower and turning out to vote just out of habit or due to sense of duty is less likely (Borg 2020). When the turnout rate is low, the Finns are likely to lose votes from the working-class segment and the Greens from their younger voters (Borg 2022). Another difficulty in the county elections for the Greens was that the residents of the capital city Helsinki, where the Greens have strong support, did not participate in the elections.

Due to low electoral threshold, the small parties, such as the Christian Democrats, but also a new party “Power Belongs to the People” (unofficial translation from Finnish “Valta kuuluu kansalle”, VKK) succeeded in getting representatives on county councils. The latter is run by strongly anti-immigrant and right-wing politicians expelled from the Finns Party, and its success very likely contributed to the Finns Party’s poor result.

Candidates are placed in wellbeing services counties, with no quota for each municipality or other arrangement in the system itself to control which municipality’s candidates get elected. When examining the votes cast in municipalities, however, in all wellbeing services counties the majority of votes cast in the municipality went to a candidate living in the same municipality (Statistics Finland 2022). This demonstrates how important the candidates’ place of residence was to the voters—especially from small municipalities—who were concerned that as an outcome of the reform the health and social services will in the future be centered on the largest cities. This concern potentially increased the turnout in the small municipalities even though in the campaigns, all parties emphasized how all their candidates were engaged in representing the whole county if elected. While voters may hold strong expectations that the councillors represent interests of their own place of residence, in practice this is very difficult, which may disappoint the voters (Wass 2022).

One very interesting and welcomed aspect from a gender-equality perspective was that in the county elections more women (53%) were elected than men. Never in the history of parliamentary nor municipal elections in Finland has the share of women among the nominated nor elected candidates exceeded the number of men. The success of women candidates is remarkable also against the background that the share of women among the nominated candidates was 45.4 percent. Women’s success is most likely associated with women having for long been heavily overrepresented in social and health care occupations but also publicly visible as experts and high-profile decision-makers in the field (e.g., the minister of social and health has often been a woman).

Indeed, out of altogether 10,584 candidates, a large share had a background as employees and/or experts of social, health, or rescue services. According to newspaper Helsingin Sanomat (13.1.2022), alone 16 percent were doctors or nurses. Alongside well-known politicians, social and health care experts also succeeded and were among the top vote-getters in all counties.

References

Arter, D. (2016). Scandinavian Politics Today. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Borg, S. (2022). Kansanvaltaa koronan varjossa – Tutkimusraportti vuoden 2021 kuntavaaleista. Helsinki: KAKS.

Borg, S. (2020). Asiakysymykset ja äänestäjien liikkuvuus. In Borg, S., Kestilä-Kekkonen, E., & Wass, H. (eds) Climate change in politics – Finnish National Election Study 2019. Helsinki: Ministry of Justice: 240–259.

Borg, S. (2019). The Finnish Parliamentary Election of 2019: Results and Voting Patterns. Scandinavian Political Studies 42(3–4): 182–192.

Couffinhal, A., Cylus, J., Elovainio, R., Figueras, J., Jeurissen, P., McKee, M., Smith, P., Thomson, S., & Winblad, U. (2016). International expert panel pre-review of health and social care reform in Finland. Reports and Memorandums of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2016:66. Helsinki: Ministry of Social Affairs and Health.

Finnish Government (2022) Regional government, health and social services reform. Online. Retrieved 14.2.2022.

Helsingin Sanomat (2022, 13 January). Aluevaalien ehdokkaista arviolta viidenneksellä on sote- tai pelastusalan taustaa – Asiantuntijuudesta on hyötyä, mutta toisaalta heillä on ”oma lehmä ojassa”, sanoo professori. Online. Retrieved 14.2.2022.

Helsingin Sanomat (2021, 8 November). Kokoomus ja vihreät käyttämässä aluevaaleihin selvästi vähemmän rahaa kuin kuntavaaleihin, Sdp:n budjetti suurin. Online. Retrieved 14.2.2022.

Kangas, O. & Kalliomaa-Puha, L. (2018). Finland: The government’s social and healthcare reform is facing problems. European Social Policy Network (ESPN) Flash Report 2018/2.

Raunio, T. (2021). Finland: Forming and Managing Ideologically Heterogeneous Oversized Coalitions. In Bergman, T., Bäck, H., & Hellström, J. (eds) Coalition Governance in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 165–205.

Statistics Finland (2022). County elections 2022, result of the control calculation. Online. Retrieved 14.2.2022.

Wass, H. (2022, 19 January). Siltarumpu ja stetoskooppi kainalossa aluevaltuustoon. Kuntalehti.

Westinen, J. (2015). Cleavages in contemporary Finland: a study on party-voter ties. Turku: Åbo Akademi.

von Schoultz, Å. (2018). Electoral Systems in Context: Finland. In Herron, E.S., Pekkanen, R.J., & Shugart, M.S. (eds), Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 601–626.

Yle News (2022, 23 January). County elections: NCP clinches win as ‘big three’ make a comeback. Online. Retrieved 14.2.2022.

Yle News (2019, 8 March) Sipilä: Gov’t resignation was “a major disappointment”, a “personal decision”. Online. Retrieved 11.4.2022.

citer l'article

Josefina Sipinen, Regional elections in Finland, 23 January 2022, Oct 2022,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue