Regional elections in Vorarlberg, 13 October 2024

Wolfgang Weber

Guest Professor at the Vorarlberg University of Applied SciencesIssue

Issue #5Auteurs

Wolfgang Weber

Issue 5, January 2025

Elections in Europe: 2024

Framing the Vorarlberg province in Austrian history

Vorarlberg is the westernmost Austrian province. It shares a common border with Germany in the North, Switzerland in the West and Liechtenstein in the South. The Arlberg mountain range in the East has been understood as a “natural border” towards Austria and the neighboring Tyrol Province for centuries. Until the collapse of the Habsburg Empire in November 1918, the central administrative authorities for Vorarlberg were based in Innsbruck, the Tyrolean capital. Only after the declaration of the First Austrian Republic on 12 November 1918 did Vorarlberg become an independent self-ruled entity. In May 1919, four-fifths (81%) of the electorate voted in favour of union with Switzerland. The Peace Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye on 10 September 1919 halted such plans (Segesser et al., 2021). Since then, Vorarlberg has established itself as a “special case” within Austrian politics, a province that is seen and understands itself as politically and economically “different” from the other eight Austrian provinces. Some statistical figures indeed bear witness of this “special case” (Walther, 2024).

The conservative People’s Party (ÖVP) and its predecessor in the First Republic has won all elections to the regional parliament between 1919 and 2020. Between 1919 and 1999 as well as between 2004 and 2014, it won with an absolute majority. Still, the ÖVP always formed local governments in coalition with one or two opposition parties voluntarily. The Vorarlberg constitution does not require the use of a proportional representation system to appoint embers of the executive, unlike in other Austrian provinces such as Lower Austria or Vienna (Motter, 2024).

From 1945 to 1974, the Vorarlberg government was a joint government of all three parliamentary parties. From 1974 to 1999 and between 2004 and 2009, a non-minimal coalition government of ÖVP und FPÖ, the Freedom Party of Austria, was in charge. Between 1999 and 2004, a minimal coalition government between these two parties was in power. Finally, from 2014 to 2024, another minimal coalition government between the ÖVP and the Green Party ruled. Only the 2009-2014 legislative period saw a single-party ÖVP government (Broger, 2024).

Such a dominance of one political party over a century is a distinguishing mark of Vorarlberg politics in the 20th and 21st century. Besides the federal capital (and province) of Vienna and Lower Austria, none of the Austrian provinces has experienced such a long-lasting control of one party over parliamentary and governmental life. Vorarlberg shares some economic figures with Vienna, too. After the federal Austrian capital, it is the province with the highest degree of industrialization and the biggest proportion of migrants amongst its resident population (Weber, 2024a).

Contextualizing the election campaign 2024 in Vorarlberg’s past and presence

In 2024, the campaign for the regional parliament was reduced to a period of two weeks in the first half of October. This was due to the fact that the elections to the national parliament took place in Austria on 29 September 2024. It was not the first time in Vorarlberg political history that national and regional parliamentary elections were held in such temporal proximity. The first two elections after Austria’s liberation from the Nazi dictatorship took place on the same day, on 25 November 1945 and 9 October 1949, respectively (Weber, 2004).

Similar to these two early democratic campaigns, in 2024 the electoral discourse focused more on national than on regional issues. The high costs of living and housing were long-running issues on both levels (ORF, 2024a). However, in contrast to the two national elections of 1945-49, this time around the distance between the winner and runner-up in the national election was much smaller: only 1,99 percentage points separated the ÖVP from the FPÖ. This was the tightest difference in any national election in Vorarlberg since 1945 (Weber, 2004).

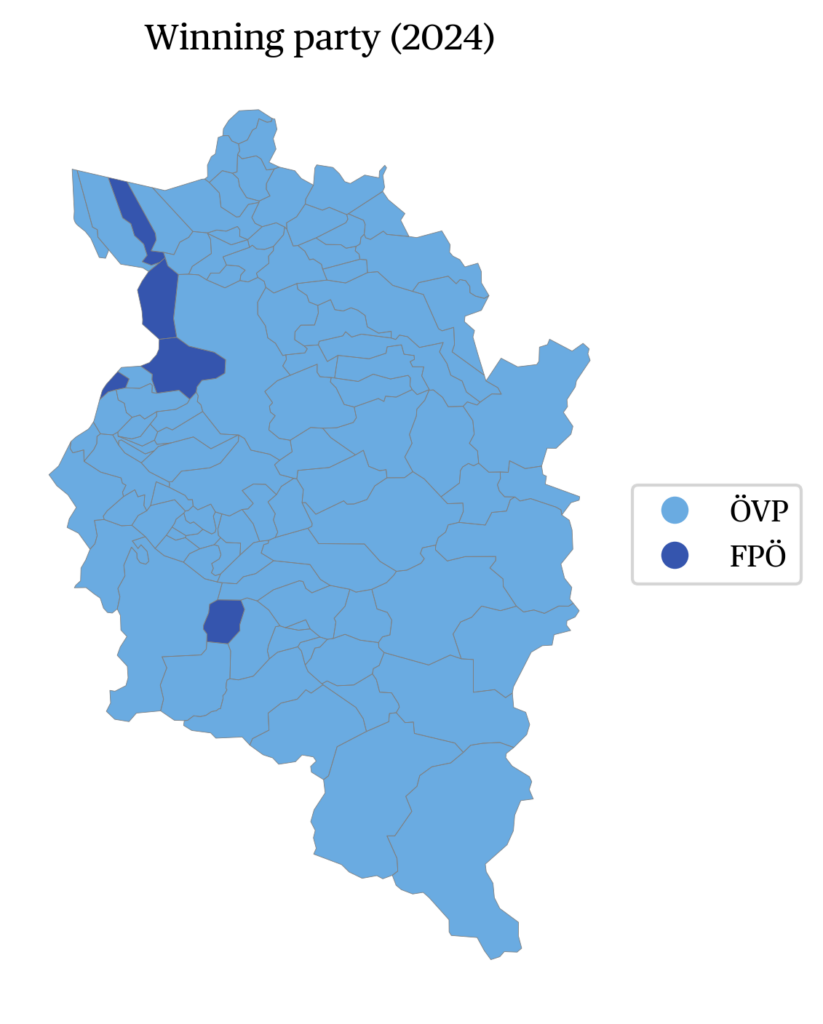

In general, the ÖVP had always performed worse in national than in regional elections in Vorarlberg since 1945. However, its lead had always been double-digit (Weber, 2004). To make things worse for the long-ruling ÖVP, on 29 September 2024 the party also came out second after the FPÖ in several Vorarlberg communities such as the town of Bludenz, the market towns of Lauterach and Lustenau and several small villages such as Brand or Ludesch. In one of the four Vorarlberg constituencies, Dornbirn, the FPÖ took first place (Nationalratswahl, 2024). This was a premiere in 105 years of democratic elections in Austria’s westernmost province.

Such results made it likely that the ÖVP would not only lose the position of province Governor (Landeshauptmann) following the regional election of 13 October 2024, but also its more than one-hundred-year-old record of finishing first in any election, be it national, regional or communal. Therefore, the ÖVP decided to start an offensive campaign focusing on its goal to remain the largest party in Vorarlberg. Winning the election was linked to the job of the Governor, which has been in ÖVP hands since 1945 – and in the hands of its historical predecessors since 1890. Its campaign was almost exclusively focused on incumbent ÖVP Governor Markus Wallner and his long-lasting service for the province. Voters were reminded that “Vorarlberg comes first” and that Wallner was a guarantee for this approach (ÖVP slogan: “Vorarlberg geht vor – Wallner”).

The opposition parties FPÖ and SPÖ opposed this message by stressing that Vorarlberg needs to get back on track (FPÖ: “Vorarlberg wieder auf Kurs bringen”) or that it can perform better (SPÖ: “Vorarlberg kann’s besser”). In their campaigning, both avoided a direct critique of the ÖVP and its Governor. They did not argue with content, but with very general statements without any programmatic sharpness.

It was up to the other parties to fill the election campaign with ideological demands and programmatic statements. The Liberal Party (Neos) called for change in regional politics and presented itself as a power of change (“Die Reformkraft”). The Green Party prolongued its national election campaign and presented itself as the only party which guarantees climate protection and a safe future (“Wähl’ Klima”). Small parties such as an alliance of migrant and grass root organizations made pleas for more democracy and participation (“Dein Recht auf Mitsprache”). The KPÖ (Communist Party) was the only one to focus on social policy issues (“KPÖ: Eine Stimme für leistbares Leben”).

Data, numbers and facts on election day

271,882 inhabitants over 16 years of age were eligible to vote in four constituencies. A total of 36 parliamentary seats were at stake. Only 185.182 people went to the polls, resulting in a turnout of 68.1 per cent. This represents the second highest turn-out since the abolition of compulsory vote in 2004. The lowest was in 2004 with 60.1 per cent (Landtagswahl, 2024).

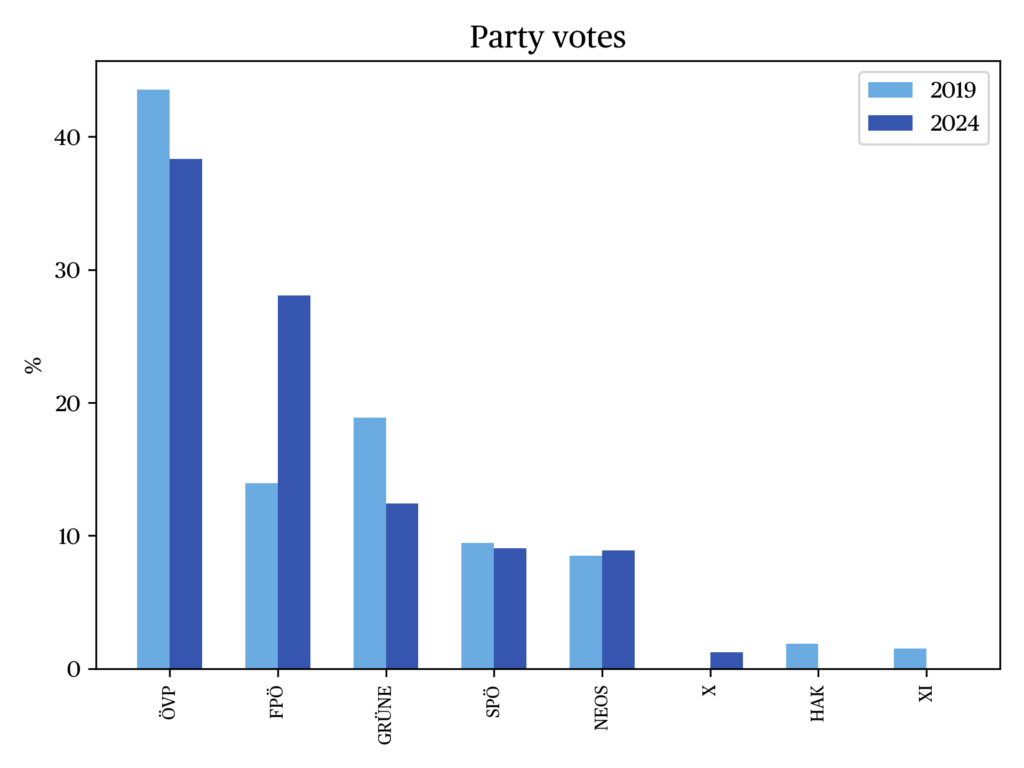

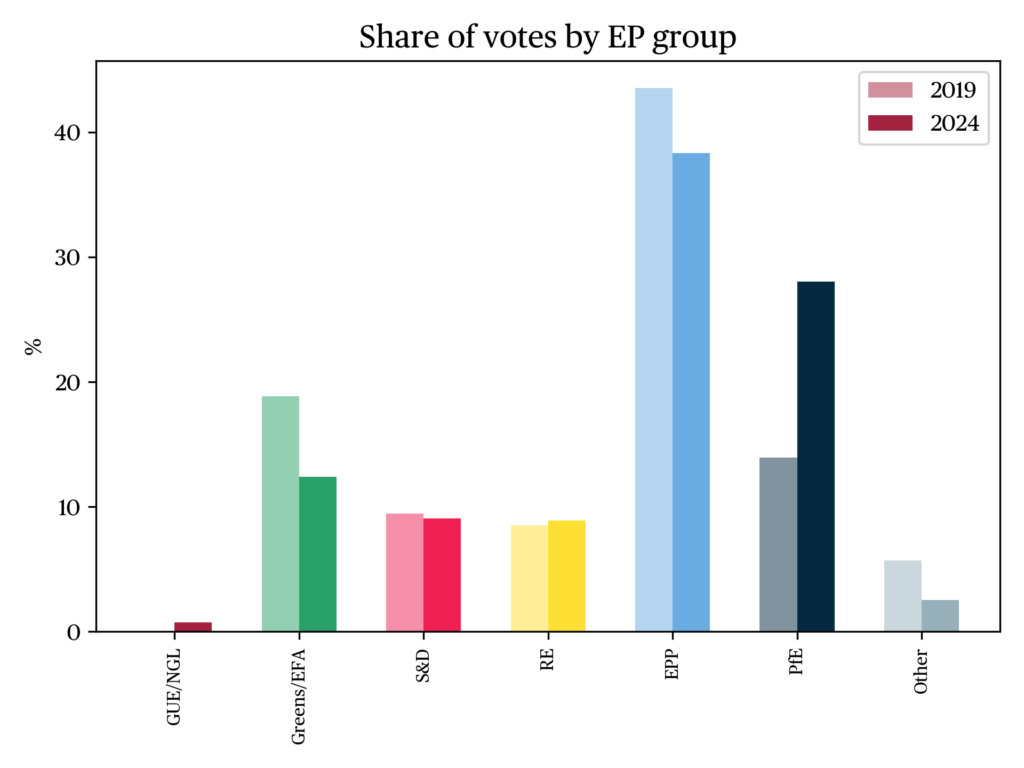

The decline of the ÖVP, which started from an absolute majority of 54.9 per cent in 2004, continued on 13 October 2024. Compared to the last election in 2019, the ÖVP lost 5,2 percentage points and landed at 38,3 per cent of the overall vote. Its coalition partner in government in the past ten years, the Greens, landed at 12.4 per cent of all votes. This was a loss of 6,7 percentage points compared to 2019. The Liberal and Social Democratic Parties, Neos and the SPÖ, stabilized at nine per cent. Four smaller parties, among which the KPÖ, failed to reach the 5-percent threshold needed to enter Vorarlberg parliament (Moser, 2024).

Like a fortnight before in the national parliamentary election held on 29 September 2024, the only winner in the regional ballot was the FPÖ. The Freedom Party won 28.0 per cent. Compared to the last election in 2019, this was a gain of 14.1 percentage points, the largest a single party ever managed since the first democratic elections to the Vorarlberg parliament in April 1919. It was also the best result the FPÖ showed since 1945, outbidding its best performance of 1999, when the party took 27,4 per cent of the vote with a turnout of 87,8 per cent due to compulsory voting (Landtagswahl, 1999)

Nevertheless, the gap between the FPÖ and the frontrunner, the ÖVP, was in the double digits. A ten percent lead of the ÖVP empowered it to shape the narrative on election night, stating that the ÖVP and its Governor are the winners of the day, despite losing voters in absolute numbers compared to 2019 and reaching the worst election result of any conservative party in Vorarlberg since 1919 (Weber, 2024b).

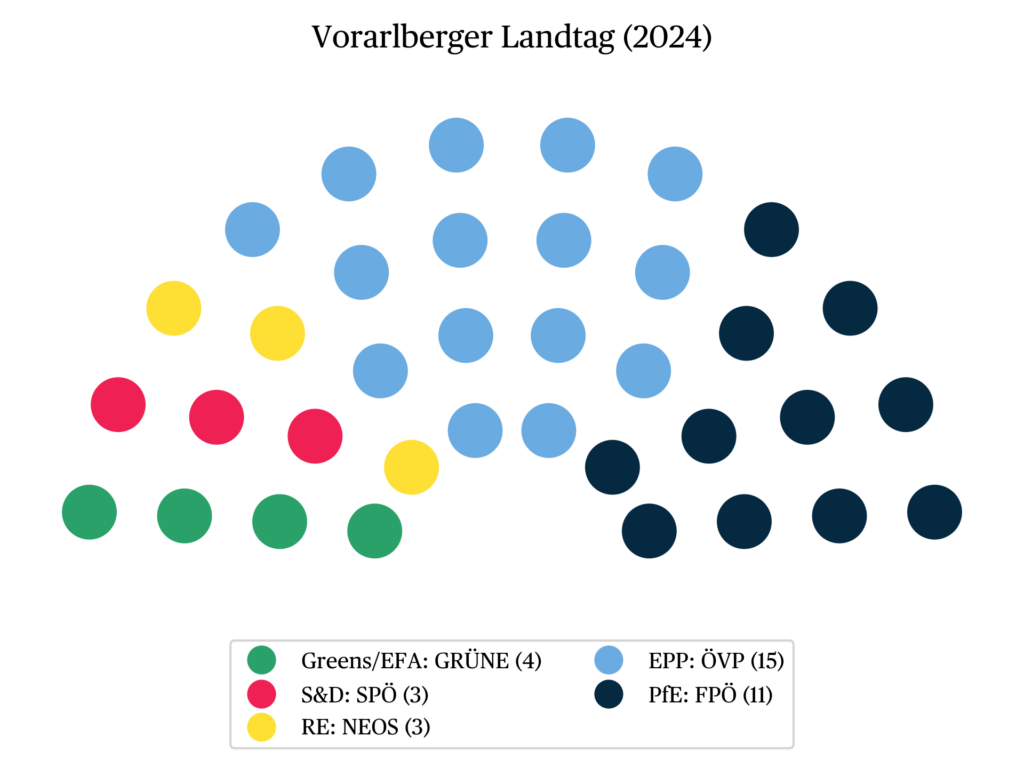

The media and the ÖVP’s competitors in the run for regional parliamentary seats quickly approved this narrative of an ÖVP victory by pointing out that the Conservatives clearly took first place with 70,638 votes and 15 of the 36 seats in the Vorarlberg parliament. The FPÖ came in second with 51,639 votes and 11 seats. 22,926 votes and four seats went to the Greens, 16,713 votes and three seats to the SPÖ and 16,477 votes and three seats to Neos (Landtagswahl, 2024).

Against the background of these figures, all five parties which were elected to the Vorarlberg parliament agreed on election night that it was the winning party’s responsibility to form a new government under the leadership of the ÖVP and its Governor Markus Wallner. In theory, Waller had two government options. The ÖVP could either form a government with its former coalition partner, the Green Party. Such a coalition government would hold a majority of 19 out of 36 seats. Alternatively, the ÖVP could choose to form a joint government with the FPÖ, which would give the new executive a two-third majority of 26 seats in parliament (ORF, 2024b).

According to the regional constitution, the Vorarlberg government must have seven members including the Governor and his or her deputy. In the past, at most two ministers went to smaller coalition partners. On election night, Governor and ÖVP leader Markus Wallner decided to begin coalition talks with each of the four parties in parliament and decide quickly with whom he will have more detailed negotiations to form the future Vorarlberg government. Four days after the election, the ÖVP und FPÖ announced that they were ready for more detailed conversations about a joint government. On 21 October 2024, they started coalition talks. By 5 November 2024, one day before the newly elected Vorarlberg parliament was sworn in, the ÖVP and FPÖ announced that they had agreed on forming a coalition government for the legislative period 2024-2029. The final division of portfolios and the choice of the ministers in charge reflected the ÖVP’s better negotiation position: five out of seven government members including the Governor wer appointed by the ÖVP. The FPÖ has only two, including the deputy governor (Entner-Gerhold, 2024).

Potential consequences of the Vorarlberg elections for Austrian federal politics

The coalition agreement between ÖVP and FPÖ in Vorarlberg means that there is a fifth regional government in Austria which consists of a centre-right and a right-wing populist party. Bearing in mind that on a federal level, the FPÖ, despite winning the election to the national parliament on 29 September 2024, failed to find a coalition partner, a fifth participation in a regional executive may be read as a compensation for the loss of national government power. In addition, the FPÖ is also present in the proportionally elected Viennese government, even though its representative there does not hold a portfolio.

Overall, the FPÖ is a governmental force in six out of nine Austrian provinces. In Styria, it leads a coalition governement with the ÖVP and holds the office of the Governor. In four provincial governments, the FPÖ is the junior coalition partner. Being present in six out of nine provincial governments, the FPÖ can shape federal politics through the second chamber of parliament, the Bundesrat, which represents the Austrian provinces. After its success in the regional Vorarlberg election, one of the three Vorarlberg seats in the Bundesrat will be held by the FPÖ. In the past ten years, this seat was held by the Greens (ORF, 2024c).

The results of the Vorarlberg election on 13 October 2024 confirmed a development which opinion polls had predicted since the summer of 2023: an on-going decline of the ÖVP and Greens as the ruling parties, a double-digit increase in FPÖ vote and a stagnation of Social Democratic and Liberal forces. Currently, the electorate seems to be split into three camps of roughly similar size. Historically, this was already the case in Austria’s First Republic during the interwar period. The main task of current politics must be to define possible interfaces between the three camps and bring them together for the sake of a vibrant democracy. Otherwise, the Second Austrian Republic could be tempted to repeat the mistakes of the First Austrian Republic, which ended in civil war.

The data

References

Broger, E. (2024, 17 October). Vorarlbergs schwarz-blaue Regierungen. ORF.

Moser, M. (2024, 14 October). Zeichen stehen auf schwarz-blau. ORF.

Motter, H. (2024). Vorarlberg und seine Landtagswahlen. Thema Vorarlberg.

Nationalratswahl (2024). Nationalrat: Amtliches Ergebnis für Vorarlberg. Land Vorarlberg.

ORF (2024a, 2 October). „Elefantenrunde“ über die Zukunft des Wohnens. ORF.

ORF (2024b, 14 October). Koalitionsfrage: Schwarz-Blau mit langer Geschichte. ORF.

ORF (2024c, 14 October). Bundesrat: Ein Mandat wandert von den Grünen zur FPÖ. ORF.

Landtagswahl (2024). Landtagswahl: Endgültiges amtliches Ergebnis. Land Vorarlberg.

Segesser, D., Weber, W., & Zala, S. (Eds.) (2021). Sehr geteilte Meinungen. Dokumente zur Vorarlberger Frage 1918-1922. Forschungsstelle Diplomatische Dokumente der Schweiz, 19–24.

Entner-Gerhold, B. (2024, 5 November). Familiengeld, Deutschpflicht, Straßenbau. Was ÖVP und FPÖ in Vorarlberg planen. Vorarlberger Nachrichten.

Walther, K. (2024, 5 September). Wie tickt Vorarlberg? Hinter dem Arlberg ist vor dem Arlberg. Wiener Zeitung.

Weber, W. (2004). Hobelspäne. Landtagswahlkämpfe, Parteien und Politiker in Vorarlberg von 1945 bis 1969. Rheticus Gesellschaft.

Weber, W. (2024a). Der dominante Blick nach innen. Vorarlberg in den Jahren 1989/91. In A. Brait & M. Gehler (Eds.), Österreichs Bundesländer und die Umbrüche 1989/91. Erste Befunde und weiterführende Überlegungen (pp. 409–454). Böhlau Verlag.

Weber, W. (2024b). „Unser aller Ländle“ – nicht unser aller Kandidaturen. Migration und Inklusion als Issues bei Vorarlberger Gemeindewahlen im 20. Jahrhundert. In G. Pallaver, W. Weber, & M. Jenny (Eds.), Kommunalwahlen in Vorarlberg 1950-2020. Fakten, Prozesse, Perspektiven (pp. 225–254). Studienverlag.

citer l'article

Wolfgang Weber, Regional elections in Vorarlberg, 13 October 2024, Sep 2025,

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue