Territorial election in French Guiana, 20-27 June 2021

Edenz Maurice

Associate researcher at the Sciences Po Paris History Research CenterIssue

Issue #2Auteurs

Edenz Maurice

21x29,7cm - 167 pages Issue 2, March 2021 24,00€

Elections in Europe : June 2021 – November 2021

“There will not have been the feared thunderclap. No region was tipped over to the Rassemblement National (National Rally, RN) in the evening of the second round of regional elections on Sunday 27 June, marked by a high abstention.” This was the first lesson that Le Monde drew at 8 pm from this election. (de Royer 2021). The next day, most of the French media said the same thing. “The leaders of the right are strengthened, the left retains its five regions and the RN is in retreat,” summarized for example Franceinfo (Franceinfo 2021). However, as we (re)discovered that the electoral consultation was spread over several time zones, the established observation proved to be wrong. By switching to the left, French Guiana, with a population of nearly 280,000 inhabitants on 1 January 2018, offered one of the most unexpected outcomes in the French overseas territories.

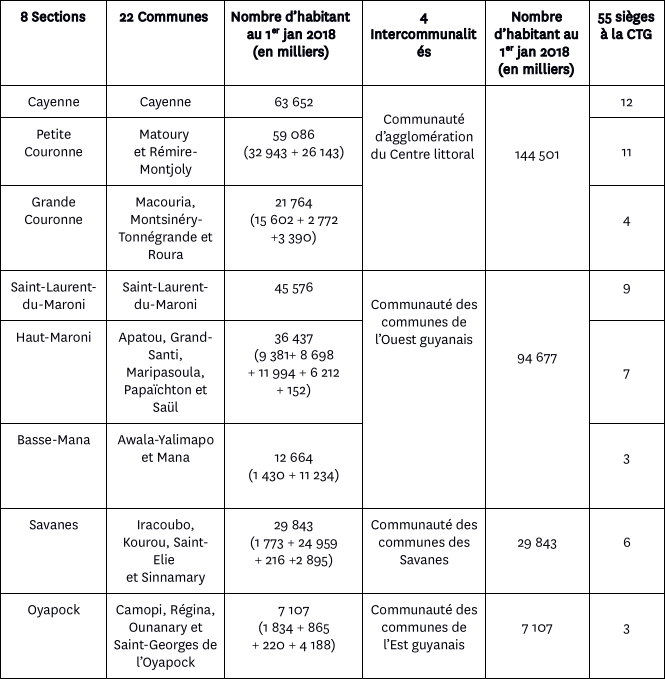

The first renewal of the Territorial Collectivity of French Guiana (CTG)

On 20 and 27 June, more than 100,000 voters were called to renew the assembly of the young CTG, which came into operation on 1 January 2016, for the first time. Due to vigorous population growth — since 2013, French Guiana has grown by 6,400 inhabitants each year — 55 seats, instead of 51, were at stake. Five of the eight electoral sections benefited from this gain of four seats, while the Savanes section, centered on the space city of Kourou, lost one. The section of Upper-Maroni, which includes isolated communes in the west, thus gained two additional territorial councillors. The section of Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni and those of the Petite and Grande Couronne, in other words the agglomerations around Cayenne, the capital of the CTG, each gained one seat.

The outgoing president, Rodolphe Alexandre, was confident and unbeaten since his defeat in the 1993 legislative elections and was re-elected in the first round. Ten candidates supported by or affiliated with his party Guyane Rassemblement (Guiana Rally, GR) had won the last municipal elections, and many local elected officials made up his list called “United and Committed to our Territory”. Alexandre, who is a close associate of Emmanuel Macron, could also proudly claim the unofficial support of La République en Marche (LREM, Renew Europe) and, more unexpectedly, the public support of the Guyanese federation of the Socialist Party (Parti Socialiste, PS, PES). The campaign of the strong man of a political game unfamiliar to a French observer thus highlighted the success of the establishment of the CTG and invited to make “the choice of competence,” because “to direct the CTG, to preside over the destiny of Guiana, that cannot be improvised!”

1

There were three lists against him, compared to eight in the December 2015 election. Unable to lead a union of the left, the MP Gabriel Serville, member of the Communist group Gauche Démocratique et Républicaine (Democratic Republican Left) in the National Assembly, took the gamble to lead his own list. The list, entitled “Guyane Kontré pour avancer” (Guiana united to move forward), included personalities from his party Peyi Guyane, the Génération.s (Generation.s) movement and Guyane insoumise (Unbowed Guiana), the local branch of La France insoumise (Unbowed France, LFI — Maintenant le peuple, Now the people). But the most important highlight consisted of the rallying of major figures from the intense social mobilization of March-April 2017. This embodied the declared desire to give voice to citizens.

Only the “Guiana” list could, however, claim to present to voters a renewed version of the plural left. Labelled as Liste d’union de la gauche et écologie (union list of left-wing ideology and ecology, LUGE), it brought together, among others, the Guyanese Socialist Party (Parti socialiste guyanais, PSG), for a long time the dominant party on the political scene, the independentists of the Movement of Decolonization and Social Emancipation (Mouvement de décolonisation et d’émancipation sociale), the ecologists, and Walwari, the formation founded in 1992 by Christiane Taubira, former Minister of Justice under the presidency of François Hollande. In addition, there were personalities of the civil society known for their opposition to the “Montagne d’Or” (Golden Mountain) project, namely the mining of a gold concession in western Guiana, which was at the heart of the public debate in 2018. Mayor of Awala-Yalimapo, symbolic capital of the indigenous Amerindian movement, Jean-Paul Fereira was called to head this list that emphasized the autonomy of Guiana, the founding leitmotiv of the Guyanese left.

Without any party, Jessi Américain, a young Maroon

2

from a working-class district of Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni and graduate of Sciences Po, finally led the list “Change of air” (Changer d’air), whose name was inspired by a poem by Leon-Gontran Damas, one of the three proponents of the Négritude.

3

Elected in March 2020 as a member of the opposition in the city council of his hometown, this newcomer intended, according to his campaign slogan, to “kill the game” by putting an end to the dominance of the current political class. As an indication of this positioning, only his list had as many women as men at list leaders in the various electoral sections.

Source : Insee Flash. Guyane-Antilles, #131, December 2020.

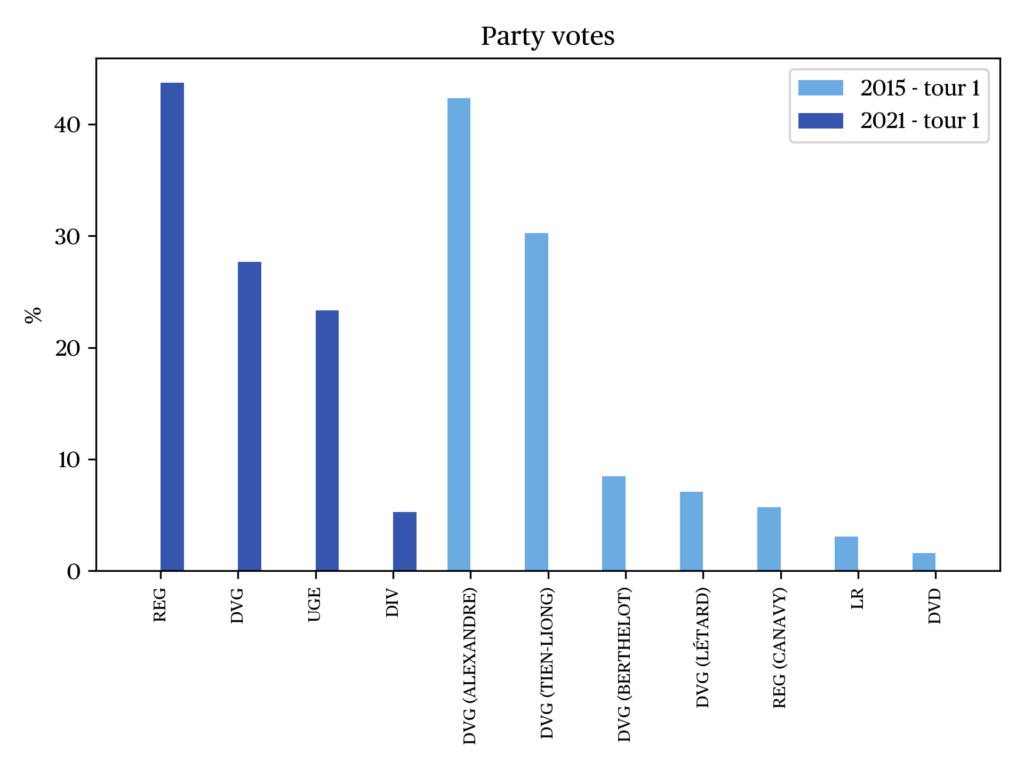

In the first round, a deceptive continuity

After the consternation of a massive abstention (65.21%), continuity seemed to prevail in the evening of the first round.

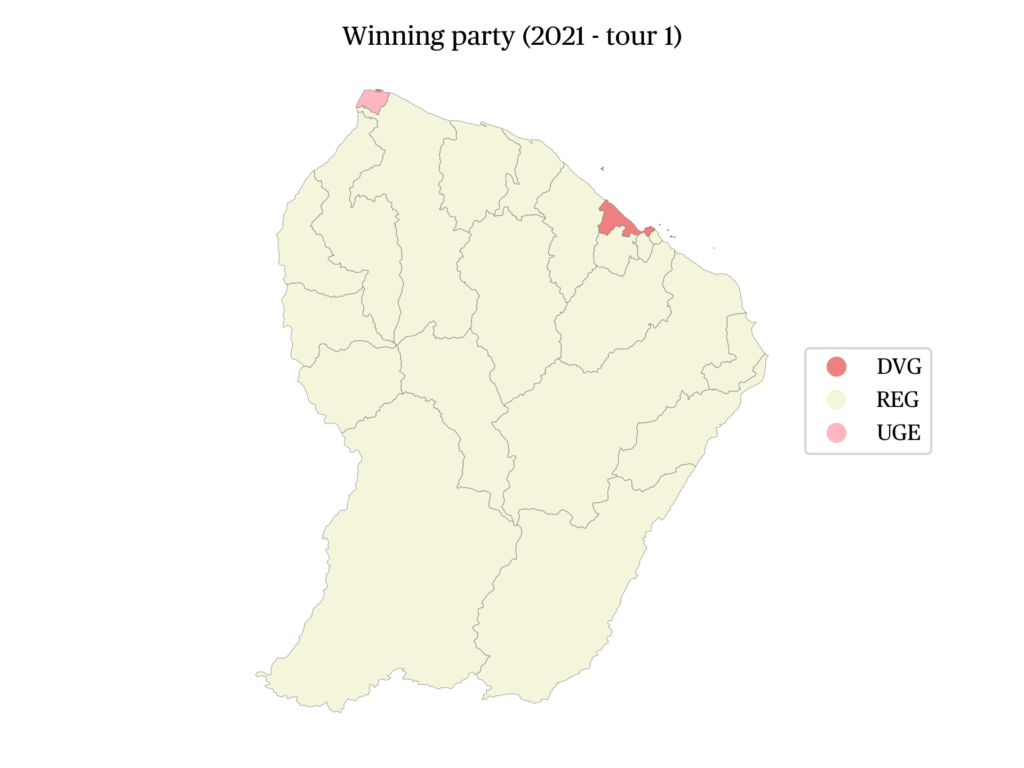

As in 2015, Alexander came largely in the lead with 43.7% of the votes cast. His list dominated seven of the eight sections and received the majority of votes in four of them. The prize went to the Oyapock area. The outgoing president reached 77.76% and was ahead of Fereira by more than 1,000 votes. In Camopi, for example, the Teko and Wayãpi Amerindians even voted 80% in his favor. The same was true of the Maroons, the majority of whom were in Upper-Maroni.

However, if we look closely, Alexandre obtained his best results in isolated rural areas, with low population densities, where, moreover, the voters were the most mobilized. For example, abstention in Oyapock was only 53.03%. Another reason for concern is that while Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni unequivocally renewed its confidence in the incumbent (54.4%), the second largest city of the Guyanese urban framework recorded the lowest turnout of the eight sections (26.68%). In addition, in the Communauté d’agglomération du Centre littoral (Agglomeration Community of the Coastal Center, CACL), the most populous among the Guyanese intercommunities, the same that Alexandre had chaired from 2001 to 2014 and which weighs nearly half of the seats to be filled, the results were disappointing. In Cayenne, ahead of Serville by more than two points, Alexandre obtained only 34.3% of the votes. The MP was also in the lead in Macouria. In Rémire-Montjoly, an upscale suburb of the capital, in Matoury, the third largest city in terms of population, and in Kourou, he even overcome the predictions by closely following Alexandre’s list. Finally, by gathering on his name 15,020 votes, almost the number of votes collected in the first round of 2015 (15,298), Alexandre had mobilized his electorate.

The arithmetic of the second round appeared more favorable for Serville who, with 27.68% against 23.34% for Fereira, had won the match on the left. The two competing left-wing lists accumulated 17,530 votes. Fereira offered strong reserves in the three western sections where the MP had his worst results. Similarly, in the section of Lower-Mana, LUGE obtained 31.84% of the votes. With a score of 5.27% authorizing him to merge, Jessi Américain reinforced the hopes for an unpredictable victory. It was indeed in Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni and in the Maroon communes of the Upper-Maroni that the greatest number of his voters were counted.

A landslide victory for the left

With the slogan “all against Alexandre,” Serville concluded on his name the union of the left in the night between 21 and 22 June. He also rallied Jessi Américain to constitute his list of the second round, renamed “Guyane Kontré pour avancer sans limites” (Guiana united to advance without limits). However, the PSG was slow to announce its support. Christiane Taubira refused to give voting indication, as her party Walwari had borne the brunt of the said union.

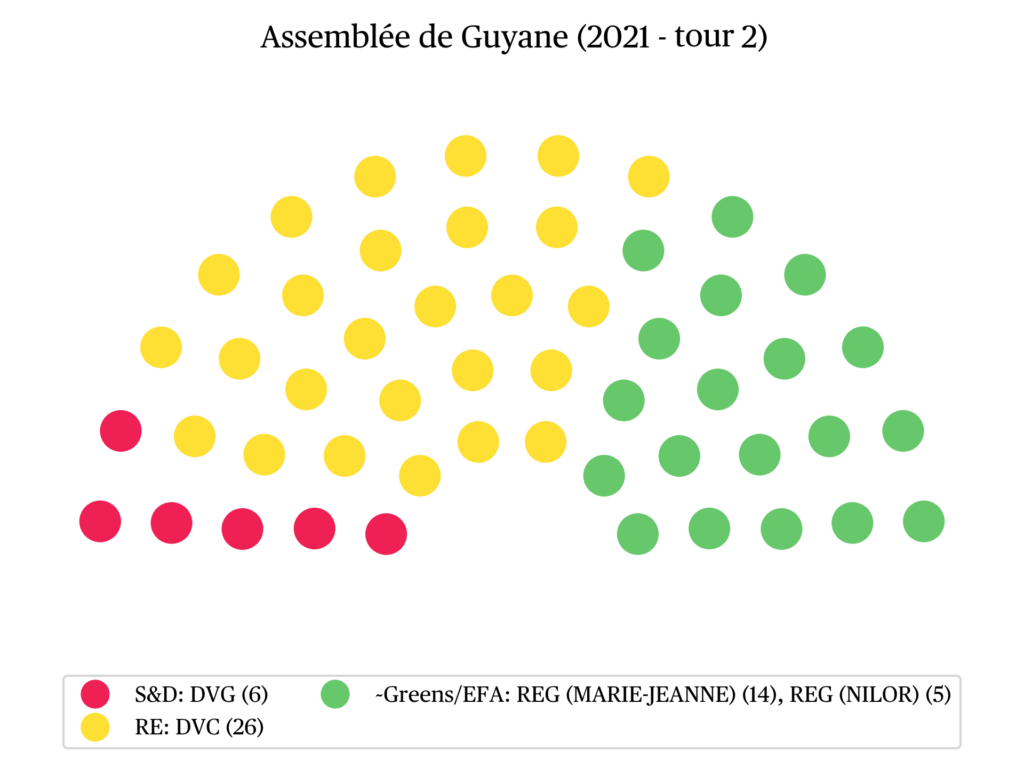

The strategy nevertheless paid off. With 54.83% of the votes, or 25,432 votes, Serville was ahead of Alexandre’s unchanged list by nearly ten points. ”It is a tidal wave in favor of change, in favor of Gabriel Serville,” reported incredulous and delighted Jean-Luc Le West, former vice-president of the Guyanese federation of the Mouvement des Entreprises de France (Movement of French Companies, MEDEF) elected in Cayenne (Guitteau 2021). De fait, à l’exception de Saint-Laurent-du Maroni, Serville conquérait tous les pôles urbains du territoire. In fact, with the exception of Saint-Laurent-du Maroni, Serville conquered all the urban centers of the territory. In Cayenne, he reached 64.4% placing Alexandre nearly thirty points behind. The Petite and Grande Couronne offered him a twenty-point lead.

“We lose in the CACL, that I set up,” reacted, stunned, the defeated candidate. “We win everywhere else, from Upper-Maroni to Lower-Mana, from Oyapock to Régina, up to Cacao. There, people have confidence in me. They know what I have done thanks to the EAFRD (European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development)”, Alexandre added (Guitteau 2021). It is true that his electorate had once again mobilized to allow him to clearly retain four sections (Lower-Mana, Upper-Maroni, Oyapock and Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni).

The fact remains that the turnout experienced an increase of more than ten points everywhere in Guiana. Between the two rounds, it went from 34.79% to 46.78%. It was in the Savanes section that abstention fell the most: 68.36% in the first round; 44.7% in the second. This increased participation overturned Alexandre, who had been in the lead a week earlier (43.6%). Serville took Sinnamary, which had voted 64% for his opponent the previous Sunday. The MP also won Kourou with a twenty-point lead. In total, the Savanes gave him the victory with 57%. In the end, the majority of the cities expressed their desire to turn the page on Alexandre.

A territory in good democratic health

In contrast to the Franch mainland, the surge in civic participation in the second round is neither unprecedented nor specific to French Guiana. “Since 2004, turnout in the second round of voting in overseas France has been systematically higher than in the rest of the country,” says Martial Foucault, holder of the recently established Overseas Chair at Sciences Po. He believes that this is a sign of a constant interest in the “role of politics” (Foucault 2021).

This election also reveals the strength of the left in overseas France. In addition to Serville’s victory, Huguette Bello, president of the Communist-based party Pour La Réunion (For La Réunion), and Serge Letchimy, leader of the Parti progressiste martiniquais (Martinique Progressive Party) founded in 1958 by Aimé Césaire, won. Their accession to power also allowed for the election of the first socialist woman, Carole Delga, PS president of the Occitanie region, at the head of the association of elected officials, Régions de France (Regions of France), for the first three years of the mandate.

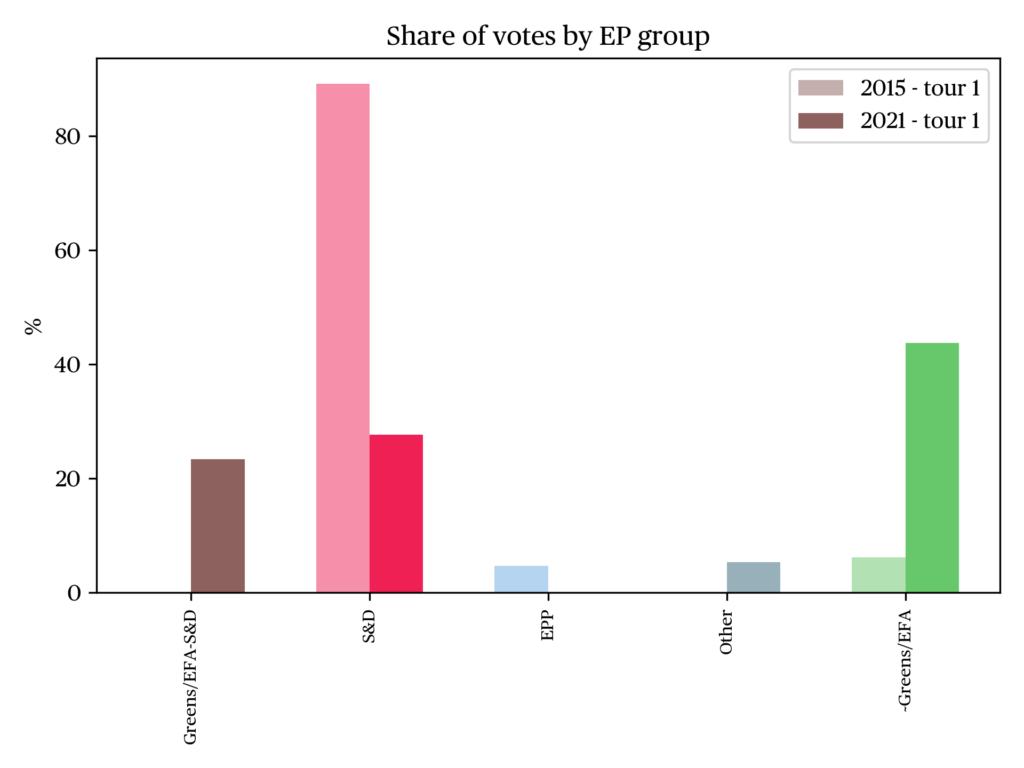

In Cayenne, the vitality of the left is all the more evident since neither LR, which is rebuilding, nor the RN, which is entangled in business, had committed themselves to the campaign. Autonomist, defiant of the State and attached to the European Union’s policy of socio-territorial cohesion, this Guyanese left is not structured around national political formations. Almost all of the leading actors in these elections were members of the PSG, which was founded in 1956 in the name of “the incompatibility of defending Guyanese interests in a party of French essence”

4

and was the main initiator of a bipolarization of local politics based on the national model (Maurice 2014). However, the Guyanese left is now composed of small political structures with a vague ideological agenda, in that they are primarily aimed at ensuring the election of their most prominent political figure.

Moreover, Alexandre saw in his defeat a desire to “dechouk” him, a dubious reappropriation of the Haitian word “dechoukage,” or the murderous intoxication that overtook the population following the fall of the dictatorial regime of Jean-Claude Duvalier (1986). In truth, the defeat is to be blamed on the wear and tear on the power of a man at the head of the regional executive for eleven years, an elected official discredited during the social revolt of March-April 2017. The desire for political alternation that was expressed at the ballot box illustrates, all in all, the good democratic health of the Guyanese space, located in a South American environment often tempted by authoritarian solutions.

The appointment of an Amerindian, the Kali’na J.-P. Ferreira, to run for the most important local political office is a further reason for satisfaction. It follows the success in the 2017 legislative elections of Lénaïck Adam (LREM), the first Maroon elected as MP from Guyana. Both testify to the new demographic and symbolic weight of indigenous societies long confined to the category of primitive populations. They consolidate the much-praised historical narrative of the three founding “races” of Guiana (Amerindian, Creole and Maroon), a local reappropriation of the myth of Brazilian racial democracy forged in the 1930s by sociologist Gilberto Freyre to create a sense of national unity.

The migratory pressure on French Guiana, where one third of the inhabitants are of foreign nationality, has led to an increasing number of xenophobic demonstrations and, as in France, to strong anti-immigration stances, with politicians accusing migration of producing insecurity and threatening the cohesion of society.

These particularly dynamic developments suggest that the potential for political innovation in overseas territories should not be understimated — neither in French Guiana nor elsewhere.

Literature

Foucault, M. (2021, July). Évolution du vote régional outre-mer 2015-2021. FOROM. Notes de recherche Outre-Mer. Online.

Franceinfo (2021, 28 June). Résultats des élections régionales 2021. Franceinfo. En ligne.

Guitteau, G. (2021, 28 June). Les Guyanais choisissent l’alternance. Guyaweb. Online.

Maurice, E. (2014). Les enseignants et la politisation de la Guyane (1946-1970). L’émergence de la gauche guyanaise, Matoury: Ibis rouge éditions.

de Royer, S. & Gatinois, C. (2021, 27 June). Résultats des élections régionales 2021 : les vainqueurs, région par région. Le Monde.

Notes

- See Rodolphe Alexandre’s program.

- Descendants of slaves who escaped from the plantations of Suriname and who, starting in the 18th century, built highly hierarchical free societies and contracted their relationship with the French authorities.

- “Grand comme un besoin de changer d’air”, published in Léon-Gontran Damas, Névralgies, Paris, Présence africaine, 1964.

- See Debout Guyane, 13 October 1962.

citer l'article

Edenz Maurice, Territorial election in French Guiana, 20-27 June 2021, Mar 2022, 78-81.

à lire dans cette issue

voir toute la revue